Abstract

We examined health status and access to care among Asian Americans by the following acculturation indicators: nativity, percent lifetime in the US, self-rated English proficiency, and interview language, to assess whether any measure better distinguishes acculturation. Data from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey were used to study the sample of 4,170 US-born and foreign-born Asians by acculturation indicators. We performed t-tests to compare differences in demographics, health status and behaviors, and access to care between the foreign-born and US-born Asians, and between various classifications within foreign-born and the US-born Asian group. Our results showed that foreign-born Asians who interviewed in English more closely resembled US-born Asians than foreign-born Asians who interviewed in languages other than English. Compared to interview language, dichotomizing the sample by other acculturation indicators showed smaller differences between the divided groups. Interview language may serve as a better measure for acculturation especially among foreign-born populations with a high proportion of limited English proficiency. In immigrant public health research studies, interview language may be used as an important covariate for health disparities.

Keywords: Acculturation, Nativity, Asian American

Introduction

The Asian American population comprises of approximately 11.9 million people or 4% of the United States (US) population. This group is expected to maintain the fastest growth rate compared to other racial and ethnic groups in the US through the year 2020 [1–3]. A significant contribution of this growth is due to immigration as 69% of Asian Americans were born outside of the US. Asians consisted of more than two-thirds of the total US foreign-born population in 2000 [1]. Therefore, it is important for researchers to monitor health status and access to care of this growing population.

One widely used method for monitoring population health and behavior is administering surveys. Recent studies using survey data suggest that disparities in health and access to care are affected by varying degrees of acculturation among Asian Americans [3–10]. These studies found that foreign-born Asians have better health than US-born Asians. Additionally, the recent Asian immigrants were shown to be healthier than both the foreign-born population with a longer duration in the US and the US-born population with respect to physical limitations, self-report health and bed days due to illness measures [7, 9]. However, conducting surveys with Asian Americans is challenging, because close to 80% of Asian Americans age 5 and over speak a language other than English at home and about 40% speak English less than “very well” [1]. Unless these studies captured those with low English proficiency in their data, generalizations about Asian Americans may not be made. This is because those with low English proficiency (LEP), which takes up a sizable proportion of Asian Americans, have distinctive characteristics from those with high English proficiency (HEP) [11].

Acculturation has been used in public health research as a health risk factor for immigrant populations, because it has been linked to discrimination, poverty, and loss of social networks, beliefs, values, or norms which lead to poorer health and barriers to care [12]. While multidimensional models of acculturation are ideal for examining these relationships, it is not feasible to include many elements required to satisfy these models in the population-based health survey data due to increased interview time and costs, unless the data collection is specifically conducted to study acculturation. As a result, the majority of public health studies use unidimensional measures for acculturation, such as nativity, length of residence in the US, percent time spent in the US, citizenship status, generational status, parent’s place of birth, cultural identification, and English proficiency [13–16].

One logical but under-utilized acculturation measure is survey interview language, for example, English versus other languages. The level of English competency necessary to carry out a survey interview may be a useful acculturation measure, in turn reflecting varying social, cultural, and economic factors. For instance, immigrants who can complete an English interview are more likely to belong to higher socio-economic classes than those who cannot. Because the socio-economic status is closely related to health, interview language itself may better explain disparities in health and access to care than other indicators used in previous research. Studies often used the self-rated English proficiency measure, with categories such as speaking English only, very well, well, not well, not at all, as a proxy for measuring acculturation [17–20]. However, the self-rated English proficiency measure brings in a subjective self-assessment potentially adding measurement problems. In addition, there is no standard way of categorizing this indicator as a measure for acculturation or a barrier to health care access. Some studies place a breakpoint between ‘very well’ and ‘well’ [20–22] while others between ‘well’ and ‘not well’ [23, 24]. The survey interview language is free from potential self-assessment biases as the needs for non-English interview is mainly determined by interviewers and does not require re-categorization.

Studies that have used survey data collected in English and Spanish found that Latinos who do not have English capability sufficient for a survey interview tend to experience more obstacles in receiving health care and have worse health status than the general population [25, 26]. Additionally, Latinos who prefer speaking Spanish have different lifestyles and health behaviors than those who prefer English [27]. Interview language was also found to be an important predictor for Pap test usage among immigrants [28]. Although interview language has the potential of being used as a proxy measure for acculturation, few studies have examined the relationship between interview language and Asian American health due to the lack of existing surveys providing Asian languages for interviews [29]. This study uses data from a population-based survey administered in multiple languages and examines health outcomes and access to care among Asian Americans by various acculturation indicators previously explored in other studies as well as survey interview language.

Methods

Data Source

This study used adult data from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS 2003) with a sample size of 42,044 including 4,170 self-reported Asians. CHIS is a state-wide random digit dial (RDD) telephone survey of California’s general population conducted biennially. The sample is drawn using geographic stratification by county and includes a state-wide oversampling of Koreans and Vietnamese by sampling areas with high concentrations of these groups at higher rates and using surname lists. The reported response rate at the screening interview based on American Association for Public Opinion Research RR4 definition (2006) was 55.9% for CHIS 2003 [30]. Of those, 60.0% of the selected adults responded to the adult interview, leading to a 33.5% overall response rate. This is close to the response rates of other RDD surveys of California, such as the 2003 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey whose overall response rate was 31.5% [31].

CHIS 2003 was administered in five languages, including English, Spanish, Chinese (both Mandarin and Cantonese), Vietnamese, and Korean. These languages were implemented to collect data from LEP populations. English CHIS questionnaires were translated into other languages using multiple forward translation method and culturally adapted [32]. English interviewers made the first contact with the sample and assigned those that experience language difficulties to the queue with indication of appropriate language. These cases were followed up by interviewers who are fluent in English and one or more of the non-English interview languages. About 28% of the Asian sample (1,177) interviewed in other languages: 10 in Spanish, 321 in Vietnamese, 324 in Korean, 276 in Cantonese, and 246 in Mandarin.

Measures

We examined demographic characteristics, self-reported health status, health conditions, and access to care indicators of California’s Asian population by different acculturation measures. We stratified the sample by nativity (US-born versus foreign-born Asians), and further classified the foreign-born Asian group by three different acculturation measures. First, we divided the foreign-born group by the length of stay in the US––whether the respondents spent more or less than 25% of their life time in the US [33–36]. (We also examined the ten-year mark, but the results were similar to our findings for percent lifetime in the US). About 68% of the foreign-born Asians in the sample spent more than 25% of their lifetime in the US.

Second, we used two different methods to categorize the self-rated English proficiency for the foreign-born Asians. First, we used the Census definition of linguistic isolation which defines the high English proficient group (HEP-1) as those who speak English only and very well and the low English proficient group (LEP-1) as those who speak English well, not well, or not at all [20–22, 36, 37]. Second, we used following categorizations defined in recent literature on immigrant populations: who report speaking English only, very well and well as high English proficient (HEP-2) group and those who speak English not well and not at all as low English proficient (LEP-2) group [23, 24]. In our sample, there were 1,992 in HEP-1 group and 2,178 in LEP-1 group, and about 92% of US-born Asians were classified as HEP-1. There were 3,155 in HEP-2 group and 1,015 in LEP-2 group, and about 99% of U.S.-born Asians were classified as HEP-2.

The last classification was based on survey interview language (English versus Asian interview languages). Although self-reported English proficiency would provide similar information, survey interview language is less likely to be influenced by the subjective nature of respondents’ self-ratings as discussed previously. Two persons with the same level of English proficiency may report their proficiency differently depending on, for example, their occupation. One person with a job that requires high English proficiency may feel that he or she speaks English not well, whereas the other person not requiring high English proficiency at work may feel that he or she is proficient. Therefore, measurement problems may arise in using self-reported English proficiency. Additionally, it is not clear how the acculturation process maps onto the self-reported proficiency scale. There is no definite answer to whether those speak English very well or those who speak very well or well should be considered acculturated. These difficulties make the interview language a convenient alternative as a proxy measure for acculturation. In our sample, there were 1,975 foreign-born Asians interviewed in English while the remainder used languages other than English.

Sociodemographic characteristics included gender, age, marital status, citizenship status, percent life in the US, education, employment status, household income, federal poverty level, and self-rated English proficiency. Health status and behaviors were measured by smoking and drinking status, overweight and obese, self-assessed general health status, number of days of having not good physical or mental health, and ever diagnosed with asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer. Health care access and utilization were assessed using current insurance status, doctor and dental visit in past 12 months, usual source of care, and had a Pap smear within the past three years and a mammogram within the past two years. We examined whether the foreign-born Asians differ from the US-born Asians with respect to these variables, whether the various proxy measures for acculturation of the foreign-born Asians differentiate the foreign-born Asians, and how well these measures may approximate acculturation with respect to health of Asian Americans.

Statistical Methods

All analyses in the subsequent sections were weighted to the population totals and adjusted for the complex sample design and nonresponse using jackknifed replicate weights in SUDAAN, Version 9.1 (Research Triangle Institute, NC, 2004). Student t-tests are performed in comparing differences of demographic characteristics, health status and behaviors, and access to care between the foreign-born and US-born Asians, and between various classifications within foreign-born and the US-born Asian group.

Additionally, estimates for foreign-born English interview, HEP-1, and HEP-2 groups were compared to those of US-born Asians using percent relative difference (%RelDiff) calculated as follows:

|

This is a unit-free measure indicating how close the estimates of different foreign-born Asian groups are from those of US-born Asians. The closer the estimate was to 0, the less the difference was between the groups.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 4,170 Asians in the sample, 82% were foreign born. Among foreign-born Asians, 1,171 (37%) completed non-English interviews and 993 (32%) spent less than 25% of their lifetime in the US. Foreign-born Asians were older, more likely to be married, and economically less privileged than US-born Asians (Table 1, columns A and B). However, when foreign-born Asians were further stratified by acculturation indicators, distinctive patterns emerged. Significant differences in household income and poverty measure by nativity disappeared between US-born and foreign-born Asians when comparing by interview language. Foreign-born Asians who interviewed in English showed higher proportion of full-time employees and a higher education level than US-born Asians. Compared to US-born Asians, foreign-born Asians who interviewed in non-English languages showed much lower average annual household income ($36,748 vs. $76,430) and had a significantly higher proportion with an educational attainment of high school or less (about 57% vs. 29%), and were full-time employed approximately 13% less. Additionally, the proportion of females among foreign-born Asians who interviewed in non-English languages was higher than that of US-born Asians. When examining self-rated English proficiency, the majority of the foreign-born English interview group reported speaking English “well” or above, whereas the majority of the non-English interview group reported less than “well.” Overall, our results showed that foreign-born Asians capable of carrying out English interviews resembled US-born Asians and had very different characteristics than foreign-born Asians incapable of carrying out English interviews. When dividing foreign-born Asians with percent lifetime spent in the US, the differences examined between Columns A and B were retained and no dramatic patterns emerged.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of Asian American population in California (CHIS 2003)

| Characteristics |

A. US born (n = 1,024) | Foreign born | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Total (n = 3,146) | C. English Interview (n = 1,975) | D. Non English Interview (n = 1,171) | E. Lifetime in US 25% + (n = 2,153) | F. Lifetime in US <25% (n = 993) | ||||||||

| % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | |

| Women | 52.04 | (1.99) | 52.64 | (0.58) | 50.05 | (0.99) | 57.97* | (1.68) | 51.86 | (1.01) | 54.40 | (1.65) |

| Age (mean in years) | 37.95 | (0.63) | 44.18*** | (0.29) | 41.49*** | (0.36) | 49.71*** | (0.57) | 44.28*** | (0.39) | 43.95*** | (0.68) |

| % Married | 41.17 | (1.94) | 67.85*** | (1.06) | 65.86*** | (1.28) | 71.94*** | (1.69) | 66.43*** | (1.25) | 71.05*** | (1.95) |

| % US Citizen | 100.00 | (0.00) | 64.58*** | (1.18) | 66.75*** | (1.47) | 60.11*** | (1.71) | 81.15*** | (1.22) | 27.19*** | (1.68) |

| Percent lifetime in US | 100.00 | (0.00) | 40.07*** | (0.59) | 45.35*** | (0.76) | 29.21*** | (0.61) | 51.82*** | (0.50) | 13.56*** | (0.32) |

| % High school or less education | 29.37 | (2.01) | 31.02 | (1.04) | 18.39*** | (1.17) | 57.02*** | (1.71) | 30.70 | (1.34) | 31.74 | (1.63) |

| % Work fulltime (20 + hours) | 55.09 | (2.05) | 56.07 | (1.14) | 62.59** | (1.45) | 42.64*** | (2.12) | 59.07 | (1.34) | 49.29* | (1.92) |

| Household income (mean in $) | 76,430 | (2,878) | 61,386*** | (1,236) | 73,355 | (1,571) | 36,748*** | (1,555) | 68,341* | (1,521) | 45,687*** | (1,733) |

| Federal poverty level | ||||||||||||

| 0–99% FPL | 8.02 | (1.23) | 17.31*** | (0.85) | 9.69 | (0.91) | 32.99*** | (1.78) | 13.67*** | (1.12) | 25.52*** | (1.78) |

| 100–199% FPL | 11.92 | (1.63) | 18.06** | (0.96) | 13.95 | (1.12) | 26.52*** | (1.66) | 15.33 | (1.06) | 24.22*** | (1.71) |

| 200–299% FPL | 13.20 | (1.68) | 13.62 | (0.78) | 12.81 | (0.92) | 15.29 | (1.36) | 14.22 | (0.94) | 12.28 | (1.21) |

| 300% FPL + | 66.86 | (2.45) | 51.01*** | (1.12) | 63.54 | (1.44) | 25.20*** | (1.60) | 56.78*** | (1.32) | 37.98*** | (1.72) |

| Self-rated english proficiency | ||||||||||||

| Speak only English | 64.78 | (1.93) | 9.19*** | (0.69) | 13.66*** | (1.01) | 0.00*** | (0.00) | 12.31*** | (0.87) | 2.16*** | (0.52) |

| Very well/well | 34.46 | (1.93) | 62.63*** | (0.99) | 78.72*** | (1.14) | 29.50* | (1.59) | 66.95*** | (1.23) | 52.87*** | (1.80) |

| Not well/not at all | 0.76 | (0.25) | 28.18*** | (0.83) | 7.62*** | (0.80) | 70.50*** | (1.59) | 20.74*** | (0.97) | 44.97*** | (1.85) |

All these estimates were compared to US-born Asian American group using t-tests

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Health Status

Table 2 shows that many health characteristics such as drinking status, general health status, number of physically unhealthy days, and lifetime asthma diagnosis, were significantly different between the US-born and foreign-born Asian. When foreign-born Asians were stratified by the interview language, more apparent and significant differences were found among non-English interview group with significantly less drinking, lower proportion of lifetime asthma diagnosis but higher proportion of diabetes, high blood pressure diagnosis, and more likely to self-rate as having fair/poor health than US-born Asians. On the other hand, the English interview group showed similar trends as US-born Asians with only significantly differences in drinking status, poor general health status, and lifetime asthma diagnosis. Relative length of stay in US did not reveal new patterns among foreign-born Asians.

Table 2.

Health behaviors and health status among Asian Americans in California (CHIS 2003)

| Characteristics |

A. US born (n = 1,024) | Foreign born | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Total (n = 3,146) | C. English Interview (n = 1,975) | D. Non English Interview (n = 1,171) | E. Lifetime in US 25% + (n = 2,153) | F. Lifetime in US < 25% (n = 993) | ||||||||

| % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | |

| Health behaviors | ||||||||||||

| % Current smoker | 14.79 | (1.66) | 13.49 | (0.82) | 13.90 | (1.16) | 12.76 | (1.16) | 14.13 | (1.05) | 12.00 | (1.14) |

| % Had alcoholic drink in past 30 days | 55.56 | (2.09) | 43.87*** | (1.16) | 47.40** | (1.51) | 36.63*** | (1.56) | 46.70*** | (1.34) | 37.50*** | (1.78) |

| % Overweight or obese | 36.99 | (2.26) | 32.13 | (1.10) | 34.30 | (1.52) | 27.63*** | (1.63) | 34.47 | (1.46) | 26.9*** | (2.07) |

| Health status | ||||||||||||

| General health status | ||||||||||||

| Excellent | 27.16 | (1.95) | 17.37*** | (0.79) | 23.20 | (1.17) | 5.30*** | (0.68) | 17.90*** | (0.99) | 16.20*** | (1.38) |

| Very Good | 34.48 | (1.78) | 29.32* | (1.09) | 34.80 | (1.48) | 18.08*** | (1.48) | 31.10 | (1.30) | 25.30*** | (1.81) |

| Good | 27.82 | (1.65) | 30.31 | (0.91) | 29.30 | (1.27) | 32.43* | (1.65) | 30.05 | (1.25) | 30.90 | (1.65) |

| Fair | 9.14 | (1.22) | 16.45*** | (0.73) | 9.60 | (0.78) | 30.57*** | (1.64) | 15.42*** | (0.91) | 18.80*** | (1.43) |

| Poor | 1.40 | (0.45) | 6.55*** | (0.55) | 3.11* | (0.60) | 13.62*** | (1.23) | 5.53*** | (0.58) | 8.83*** | (1.19) |

| Number of days of having not good physical health | 2.42 | (0.19) | 3.12** | (0.18) | 2.48 | (0.18) | 4.43*** | (0.40) | 3.08* | (0.2) | 3.21* | (0.30) |

| Number of days having not good mental health | 2.92 | (0.21) | 2.86 | (0.15) | 2.49 | (0.17) | 3.61 | (0.30) | 2.89 | (0.18) | 2.79 | (0.24) |

| % Ever diagnosed with asthma | 16.90 | (1.45) | 7.82*** | (0.55) | 8.89*** | (0.69) | 5.63*** | (1.00) | 8.29*** | (0.69) | 6.76*** | (1.10) |

| % Ever diagnosed with diabetes | 6.87 | (1.13) | 6.68 | (0.60) | 6.11 | (0.67) | 7.86 | (1.10) | 6.91 | (0.72) | 6.16 | (1.11) |

| % Ever diagnosed with high blood pressure | 19.29 | (1.34) | 22.2 | (0.97) | 20.50 | (1.14) | 25.81** | (1.59) | 23.02* | (1.26) | 20.40 | (1.78) |

| % Ever diagnosed with heart disease | 4.45 | (0.74) | 4.79 | (0.51) | 3.98 | (0.62) | 6.46 | (0.86) | 5.12 | (0.67) | 4.04 | (0.74) |

| % Ever diagnosed with cancer | 3.14 | (0.54) | 2.58 | (0.35) | 2.78 | (0.48) | 2.17 | (0.48) | 2.89 | (0.44) | 1.87 | (0.58) |

All these estimates were compared to US-born Asian American group using t-tests

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Health Care Access and Utilization

Table 3 shows that there were significant differences in health care access (current insurance coverage status, having a dental visit in the past 12 months, and having usual source of care other than ER) and health care utilization (mammogram screening in past two years) between the US-born and foreign-born populations. Compared to US-born Asians, the non-English interview foreign-born group reported significantly lower proportions of being currently insured, having a dental visit in past 12 months, having usual source of care, and receiving a mammogram and Pap smear, while English interview foreign-born Asians appeared similar to US-born Asians except for their dental visits and mammogram usage. Stratifying the foreign-born Asians by the 25% lifetime in the US mark revealed that people who spent less than 25% of their life in the US showed very similar health care access and utilization patterns as the non-English interview group.

Table 3.

Health care access and utilization among Asian Americans in California

| Characteristics | A. US born (n = 1,024) | Foreign born | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Total (n = 3,146) | C. English Interview (n = 1,975) | D. Non English Interview (n = 1,171) | E. Lifetime in US 25% + (n = 2,153) | F. Lifetime in US < 25% (n = 993) | ||||||||

| % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | |

| Health care access | ||||||||||||

| % Currently insured | 91.83 | (1.19) | 85.64*** | (0.84) | 89.88 | (0.99) | 76.93*** | (1.73) | 87.84* | (1.01) | 80.69*** | (1.51) |

| % Doctor visit in past 12 months | 78.84 | (1.80) | 79.38 | (0.87) | 80.67 | (1.11) | 76.72 | (1.60) | 80.89 | (1.07) | 75.96 | (1.60) |

| % Dental visit in past 12 months | 77.94 | (1.88) | 68.31*** | (1.02) | 71.91** | (1.26) | 60.90*** | (1.89) | 71.02** | (1.25) | 62.20*** | (1.93) |

| % Without a usual source of care | 10.04 | (1.18) | 13.70** | (0.79) | 11.92 | (1.01) | 17.34*** | (1.58) | 11.17 | (0.92) | 19.41*** | (1.40) |

| Health care utilization | ||||||||||||

| % Had a Pap smear within past 3 yrs | 77.55 | (2.33) | 73.66 | (1.41) | 78.82 | (1.8) | 64.49*** | (2.58) | 77.26 | (1.73) | 65.91** | (2.73) |

| % Had a mammogram within past 2 yrs (40+) | 68.17 | (3.04) | 55.68*** | (1.63) | 54.14*** | (1.96) | 58.13** | (2.31) | 59.30* | (2.06) | 47.13*** | (3.42) |

All these estimates were compared to US-born Asian American group using t-tests

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

We also conducted the same analyses for separate samples of Koreans, Chinese and Vietnamese, first broken down by nativity; and further stratified by length of stay with the 25% lifetime mark and interview language for foreign born groups (results not shown). We found a similar pattern for those separate ethnic groups as for Asians as a whole shown previously: interview language emerged to better differentiate acculturation than nativity or length of stay.

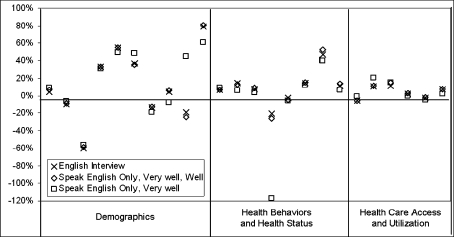

Language Proficiency as an Acculturation Measure

We examined how well different English proficiency measures reflected acculturation by dividing foreign-born Asians by the following three English proficiency measures: (1) English interview versus other language interview, (2) speak English only, very well, well (HEP-1) versus speak English not well, not at all, (LEP-1) and (3) speak English only, very well (HEP-2) versus speak English well, not well, not at all (LEP-2). The first group of each of these three measures were considered the acculturated groups and then compared to the demographics, health behaviors, health status, and health care access of US-born Asians. Figure 1 shows how each of these groups differed across all characteristics examined in Tables 1, 2, 3 compared to US-born Asians using %RelDiff as defined previously. (The order of variables in the figure follows that in the Tables 1, 2, 3.) Among the three foreign-born Asian groups, those who interviewed in English were the most similar to US-born Asians. Across all variables, estimates for the English interview group were more likely to be placed around 0, showing more similarity to the estimates of US-born Asians compared to the HEP-1 and HEP-2 groups. Additionally, the HEP-1 foreign-born Asians appeared to be more similar to the US-born Asians than the HEP-2 foreign-born group.

Fig. 1.

Percent relative difference in estimates of foreign-born Asians from US-born Asians by different language proficiency measures

Discussion

Our results showed that foreign-born Asians who interviewed in English resembled US-born Asians in demographic characteristics, health status, and access to care. The differences between the non-English interview foreign-born Asians and the US-born Asians than were more apparent and significant than those between the English interview foreign-born Asians and the US-born Asians. This implied that survey interview language may serve as a better unidimensional proxy measure for acculturation than others used previously. Additionally, differences between foreign-born and US-born Asians were dependent on the categorization of the English proficiency measure. Hence, interview language appears to be a more reliable proxy of acculturation measure, since it is more objective and thus free from self-assessment bias.

The overall findings between US-born Asians and foreign-born Asians in this study confirm what were previously documented [8]. The uniqueness of this study is that the comparisons between US-born and foreign-born Asians were made by interview language rather than citizenship status, self-reported English proficiency, and time in the US, as in most population-based studies taking into account the heterogeneity of Asian American populations [5, 7, 9, 20]. When using interview language as a proxy measure for acculturation, disparities between US-born and foreign-born Asians in chronic conditions (diabetes, asthma, hypertension) and health care utilization (doctor visits, dental visits) are larger and more widespread. Our findings coincide with a recent study on interview language and Pap testing which found Asians who interviewed in an Asian language were less likely to receive cervical cancer screening [28]. These findings are also similar with health disparities found in studies comparing US-born and foreign-born Latinos by interview language [25, 26]. Results from this study suggest interview language is an important measure to consider when reporting on the health of the Asian immigrant populations.

Prior to this study, there have been limited population-based studies on the role of interview language as a proxy measure for acculturation when presenting the health of Asian Americans. As mentioned in previous literature, language interviews that are culturally and linguistically appropriate are essential in collecting comprehensive and accurate health data of Asian American populations [28, 38]. While self-reported English proficiency is widely used, interview language provides more accurate information by minimizing self-reporting bias in English proficiency.

Despite the uniqueness of this study, it is not free from limitations involving measurement issues in the following sense. First, it may not be applicable for the entire Asian population in California, because the survey did not include all Asian languages. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that the implications of this study may have been even stronger if other languages were included, as the sample size of the foreign-born Asians interviewed in non-English languages would likely to be larger. Second, there might have been artifacts arising from the questionnaire translation influencing the results. Semantic, conceptual and normative equivalence across languages, cultures and societies is required when translating questionnaires. However, as there is no proven quantifiable way to measure or control the equivalence yet, the questionnaire translation is more of an art than a science at the current state and beyond the scope of this study.

Overall, when collected data accommodate only unidimesional measures of acculturation, nativity was found not to be a factor that explains health disparities among the Asian American population much. In fact, our findings indicate that survey interview language may provide a better understanding of health disparities compared to other acculturation indicators such as percent lifetime spent in the US and self-reported English proficiency. The results of our study also suggest that policies and public health programs should target foreign-born populations incapable of being interviewed or conversed in English to reduce disparities in health and access to care, as these groups are most likely to encounter barriers to health care access and preventive services. Furthermore, to capture representative information on population’s health, particularly from ethnic minority groups, in public health research studies and population-based surveys, it appears necessary to include other interview languages besides only English and Spanish.

This study mainly examined the unidimensional acculturation measures widely used in minority health studies. While convenient and popular, these unidimensional measures are by no means the best for determining the degree of acculturation. As acculturation encompasses a wide range of attributes that influence people’s identity, multidimensional acculturation models would be ideal for capturing the effect of immigration factors on health. Future studies may explore how to integrate unidimensional proxy indicators of acculturation commonly used in minority health studies such as those examined in the study into a single indicator. This may provide a better illustration of acculturation by featuring multiple aspects, while not compromising analytical and practical convenience.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the California Health Interview Survey 2003, the data used in this study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.US Bureau of the Census. We the people: Asians in the United States. Census 2000 special reports. Washington, DC: US Dept of Commerce; 2004.

- 2.US Bureau of the Census. Projections of the resident population: Middle series projection, 1995 to 2050, by race, Hispanic origin, and nativity. Washington, DC: US Dept of Commerce; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Bureau of the Census . The foreign-born population: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. Washington, DC: US Dept of Commerce; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thamer M, Richard C, Casebeer AW, et al. Health insurance coverage among foreign-born US residents: the impact of race, ethnicity, and length of residence. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:96–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrasquillo O, Carrasquillo AI, Shea S. Health insurance coverage of immigrants living in the United States: differences by citizenship status and country of origin. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:917–923. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGee DL, Liao Y, Cao G, et al. Self-reported health status and mortality in a multiethnic US cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;149:41–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisbie WP, Cho Y, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of Asian and Pacific Islander adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:372–379. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioral characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):903–919. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey AN, Lucas JW. Physical and mental health characteristics of US- and foreign-born adults: United States, 1998–2003. Adv Data. 2006;369:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Y, Tucker P. REACH 2010 surveillance for health status in minority communities-United States 2001–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004;53(6):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Nguyen HA, Jawad M, Kurata J. Linguistic minorities and nonresponse error. Public Opin Q. 2008;72:470–486. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfn036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, et al. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson J, Moeschberger M, et al. An acculturation scale for Southeast Asians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993;28(3):134–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00801744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe-Kim J, Okazaki S, Goto SG. Unidimensional versus multidimensional approaches to the assessment of acculturation for Asian American populations. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7(3):232–246. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung RH, Kim BS, et al. Asian American multidimensional acculturation scale: development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(1):66–80. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim BK, Li LC, et al. The Asian American values scale—multidimensional: development, reliability, and validity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2005;11(3):187–201. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephen EH, Foote K, et al. Health of the foreign-born population: United States, 1989–90. Adv Data. 1993;241:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho Y, Hummer RA. Disability status differentials across fifteen Asian and Pacific Islander groups and the effect of nativity and duration of residence in the US. Soc Biol. 2001;48(3–4):171–195. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2001.9989034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erosheva E, Walton EC, Takeuchi DT. Self-rated health among foreign- and US-born Asian Americans. Med Care. 2007;45(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241114.90614.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandula NR, Lauderdale DS, Baker DW. Differences in self-reported health among Asians, Latinos, and non-Hispanic whites: The role of language and nativity. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green AR, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza ATR, Massagli MP, Phillips RS, Lezzoni LI. Interpreter services, language concordance, and health care quality: experience of Asian Americans with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1050–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Tang H, Shimizu R, Moon MS. English language proficiency and smoking prevalence among California’s Asian Americans. Cancer. 2005;204(12):2982–2988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponce NA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health status among older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):786–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikman-Liff B, Mondragón D. Language of interview: relevance for research of Southwest Hispanics. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1399–1404. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.11.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu SM, Nyman RM, Kogan MD, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH. Parent’s language of interview and access to care for children with special health care needs. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:181–187. doi: 10.1367/A03-094R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi A, Jenks E. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women, infants, and children. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):98–105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponce NA, Chawla N, Babey SH, Gatchell MS, Etzioni DA, Spencer BA, Brown RE, Breen N. Is there a language divide in pap test use? Med Care. 2006;44:998–1004. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233676.61237.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frayne SM, Burns RB, Hardt EJ, Rosen AK, Moskowitz MA. The exclusion of non-English speaking persons from research. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02603484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys (4th edn). Lenexa, KS: AAPOR; 2006.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003 behavioral risk factor surveillance system summary data quality report. 2004. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Data/Brfss/2003SummaryDataQualityReport.pdf. Accessed October 2007.

- 32.Ponce NA, Lavarreda SA, Yen W, Brown RE, DiSogra C, Satter DE. The California health interview survey 2001: Translation of a major survey for California’s multiethnic population. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Burke N, Nguyen T, Acorda E, Thai H, Qu P, Jackson JC. Pap testing adherence among Vietnamese American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson J, Moeschberger M, Chen MS, Kunn P, Jr, Wewers ME, Guthrie R. An acculturation scale for Southeast Asians. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993;28:134–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00801744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Demographic predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:62–68. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin HB, Bruno R. Language use and English-speaking ability: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. October 2003.

- 37.Siegel P, Martin E, Bruno R. Language use and linguistic isolation: historical data and methodological issues. US Census Bureau: February 12, 2001.

- 38.Hunt S, Bhopal R. Self reports in research with non-English speakers. BMJ. 2003;327:352–353. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]