Summary

Adaptive processes within cerebellar circuits, such as long-term depression and long-term potentiation at parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses, have long been seen as important to cerebellar motor learning, and yet little attention has been given to any possible significance of these processes for cerebellar dysfunction and disease. Several forms of ataxia are caused by mutations in genes encoding for ion channels located at key junctures in pathways that lead to the induction of synaptic plasticity, suggesting that there might be an association between deficits in plasticity and the ataxic phenotype. Herein we explore this possibility and examine the available evidence linking the two together, highlighting specifically the role of P/Q-type calcium channels and their downstream effector small-conductance calcium-sensitive (SK2) potassium channels in the regulation of synaptic gain and intrinsic excitability, and reviewing their connections to ataxia.

Keywords: episodic ataxia type 2, long-term depression, long-term potentiation, P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel, Purkinje cell, SK2 channel

Motor coordination and plasticity

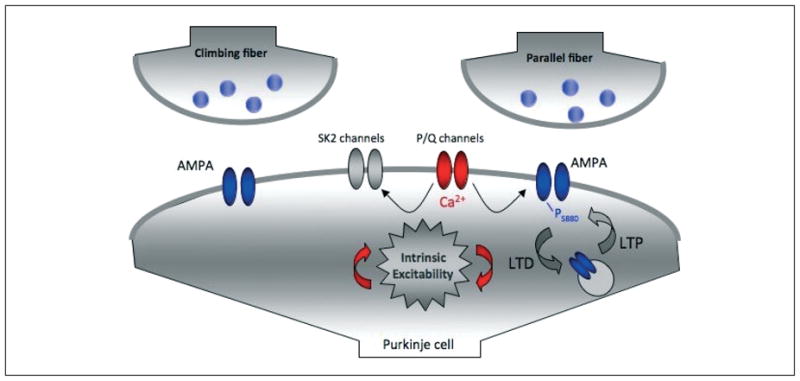

Ataxia, as generally defined, is a deficit in motor coordination that manifests itself as unsteadiness in gait and is often accompanied by neurological deficits such as dysmetria, asynergy, and nystagmus. The origin of many forms of ataxia can be traced back to deficits in the cerebellum, which plays a role in motor coordination and the fine adjustment of movements. It is widely assumed that gain control within cerebellar circuits is made possible by forms of synaptic plasticity, for example long-term depression (LTD) at parallel fiber (PF)-Purkinje cell synapses, and its counterpart, long-term potentiation (LTP; 1,2). PF-LTD is observed after paired PF and climbing fiber (CF) activity and results in a reduction of the excitatory drive to Purkinje cells, which in turn reduces the overall level of inhibition that the GABAergic Purkinje cells deliver to the deep cerebellar and vestibular nuclei (3). In contrast, PF-LTP is induced by PF stimulation alone and might act as a reversal mechanism for LTD (4,5). PF-LTD depends on large calcium transients and the activation of PKC and αCaMKII (2,6), while PF-LTP depends on more moderate calcium transients and the activation of protein phosphatases 1, 2A, and 2B (7,8). LTD and LTP also exist at other types of synapses within the cerebellar circuit, for example in the granule cell layer (9), but this review focuses on bidirectional plasticity at PF-Purkinje cell synapses (Fig. 1 over).

Figure 1.

P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels affect synaptic plasticity and intrinsic excitability. P/Q channel-mediated calcium influx plays a role in controlling the direction of synaptic gain change at parallel fiber synapses onto cerebellar Purkinje cells. At the same time, small-conductance calcium-activated SK2-type potassium channels are selectively activated by calcium influx through P/Q channels. SK2 channels modulate the spike output of Purkinje cells and put a ‘brake’ on spine calcium signaling which, in turn, plays a role in synaptic plasticity.

Deficits in cerebellar synaptic plasticity, for example resulting from genetic manipulations in mice, have been shown to result in an impairment of cerebellar motor learning (1). Here, we wish to address the question of whether synaptic plasticity/learning deficits result in ataxia. In other words, are the fast gain adaptation mechanisms likely mediated by the synaptic plasticity required for proper cerebellar processing and, consequently, motor coordination? In this paper we examine the available evidence on the link between plasticity dysfunction and ataxia, focusing specifically on those ataxias caused by deficits in signaling factors known to play a role in synaptic transmission and plasticity.

P/Q-type channels and synaptic integration

While many forms of ataxia are polyglutamine diseases (for example, the spinocerebellar ataxias or SCAs) that affect nuclear signaling and developmental pathways (10,11), a few qualify as channelopathies, which affect synaptic integration and plasticity. Among these are spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6), which is at the same time a polyglutamine disease and a channelopathy (for discussion see 11,12), and episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2), both of which result from a mutation in CACNA1A, the gene encoding for the α-1a subunit of the P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (13). These calcium channels are abundantly expressed in Purkinje cells and gate ~90% of their high-voltage activated calcium influx (14,15). P/Q-type channels are involved in transmitter release at synaptic terminals and play a role in adjusting spike firing properties in neurons. For example, tottering mice (tg), which suffer from a spontaneous point mutation in the CACNA1A gene, show a dramatic disruption in the regularity of Purkinje cell spike firing and exhibit gross motor deficits similar to those seen in human patients suffering from the CACNA1A-related ataxias SCA6 and EA2 (16).

Purkinje cells provide the sole output of the cerebellar cortex, and thus the regulation of synaptic efficacy at the thousands of excitatory PF synapses that a Purkinje cell receives is critical for adjusting the gain of motor control. The role of P/Q-type calcium channels in PF-LTD and -LTP induction has not been specifically addressed yet, which is partially due to the fact that genetic or pharmacological reduction of P/Q-type channel activity would have unspecific effects such as reduction of transmitter release, in addition to its effects on dendritic calcium signaling. Nevertheless, it has been shown that P/Q-type channels contribute to calcium transients/complex spikes that result from CF activity (17,18; for review see 19). Although under high activity conditions PF-LTD can result from PF stimulation alone (e.g. 20), isolated PF activity more typically results in LTP induction, and the switch towards LTD occurs upon CF co-activation and the associated larger calcium transients (5). Given the proposed importance of LTD to various forms of cerebellar-dependent motor learning, it is indeed plausible that P/Q-type channels are an important component of the cellular machinery that drives these processes.

Synaptic plasticity and motor coordination

Are LTD- and LTP-like processes necessary for proper motor coordination? In other words, can ataxia result from impaired synaptic plasticity? Genetically modified mice allow us to address these questions by correlating synaptic plasticity deficits studied in vitro with motor coordination/motor learning deficits monitored in vivo. It has been shown that genetically modified mice with deficient P/Q-type channel function (α1A knock-outs; tottering; leaner) are ataxic (for example, 21). The vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) performance is normal in heterozygotes, but strongly affected in homozygotes (α1A knock-outs; leaner, 22). However, as mentioned above, these mouse models have not been tested with regard to LTD/LTP deficits. Table I summarizes mouse models targeting other molecules that play a role in LTD (or LTP) induction. Basic motor performance was tested using simple tests such as the rotorod test. In addition, in all these studies eye (VOR) and/or eyelid movements (eyeblink) were examined. These tests were applied to monitor motor learning deficits in cerebellar motor learning tasks, such as VOR gain adaptation and associative eyeblink conditioning. Here, we focus on basic motor performance. LTD was impaired or entirely blocked in mice with deficits in the function of type 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1; 23), protein kinase C (24), cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (25), αCaMKII (6) and βCaMKII (26). All these receptors/enzymes play a significant role in LTD induction. Surprisingly, the majority of these different types of mice are not ataxic. Exceptions are mGluR1 knock-out mice, which are ataxic, but show normal eyeblink responses, and βCaMKII knock-out mice, which are severely ataxic. Thus, impairment of LTD does not necessarily result in ataxia. Likewise, selective LTP impairment in mice with a Purkinje cell-specific knock-out of the protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin) does not result in outright ataxia (8).

Table I.

Motor coordination in LTD/LTP-deficient mice

| Mouse | LTD | LTP | Ataxia | Eyeblink | VOR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mGluR1 | no | yes | no | Aiba et al., Cell 1994 (23) | ||

| L7-PKCI | no | no | no | no | De Zeeuw et al., Neuron 1998 (24) | |

| cGKI | no | no | no | Feil et al., J Cell Biol 2003 (25) | ||

| αCaMKII | no | yes | no | no | Hansel et al., Neuron 2006 (6) | |

| βCaMKII | no | no | yes | van Woerden et al., Nat Neurosci 2009 (26) | ||

| L7-PP2B | yes | no | no | no | no | Schonewille et al., Neuron 2010 (8) |

Note that the term ‘ataxia’ is not used as clinically defined. Here, this term is used whenever general motor coordination deficits are observed (for example in the rotorod test), thus reflecting the level at which ataxia can be assessed in mouse models. In the ‘eyeblink’ and ‘VOR’ groups, ‘no’ indicates that motor performance was not affected. In the other three groups, a ‘no’ describes the absence of LTD/LTP or ataxia, respectively. Abbreviations: mGluR1=type 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor; PKCI=protein kinase C inhibitor; cGKI=cGMP-dependent protein kinase I; CaMKII=calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; PP2B=protein phosphatase 2B

Synaptic plasticity mechanisms, such as LTD and LTP, are generally considered cellular correlates of cerebellar procedural learning, in very much the same way that their counterparts in hippocampal and neocortical circuits are seen as responsible for forms of declarative learning. It thus comes as a surprise that there is no obvious correlation between deficits in LTD/LTP and motor coordination. It is very possible that in these mice, genetic manipulations lead to compensatory upregulation of signaling factors that can partially take over the role of the affected proteins. Still, this compensatory upregulation, if present, is seemingly insufficient to restore synaptic plasticity, and yet there is no reliable impairment of motor coordination. It seems more likely that intact motor coordination requires adaptation processes that are not equivalent to LTD/LTP, for example by operating on a significantly slower time scale (weeks/months rather than minutes). This hypothesis is supported by the observation that in most mouse models shown in Table I motor learning (as assessed by VOR gain conditioning and/or eyeblink conditioning) is affected (not shown). Basic motor performance seems to be unaffected by the absence of mechanisms that allow for fast adaptation of motor gains. In any case, we have to conclude that ataxia does not seem to result from impaired synaptic plasticity. It is still possible that deficits in LTD/LTP contribute to specific ataxia components, such as the inability to adapt to sudden environmental pertubations, fast VOR gain changes (27) or, in a specifically human context, disturbances in verbal fluency. Clearly, more study is required on this issue.

SK2 channels and ataxia

P/Q-type channel-mediated calcium influx not only plays a key role in synaptic plasticity at PF-Purkinje cell synapses, but also regulates Purkinje cell excitability and spike firing by activating calcium-sensitive potassium channels. Small-conductance calcium-activated SK2-type potassium channels affect Purkinje cell intrinsic excitability and have been shown to shape the spike firing output of these cells (Fig. 1; 28). As Purkinje cells provide the sole output of the cerebellar cortex, SK2 channels thus have a direct impact on cerebellar function. Several lines of evidence suggest that suboptimal SK2 channel activation could be involved in the pathogenesis of EA2, which as previously mentioned is a P/Q-type channelopathy. First, SK2 channels are exclusively activated by calcium influx through P/Q-type calcium channels (29). Second, the application of SK channel activators EBIO and chlorzoxazone leads to a significant improvement in motor coordination in ataxic tottering and ducky mice, which have mutations in the P/Q-type channel subunit genes α1A and α2δ2, respectively (30,31). Previous studies in both tottering and ducky mice have shown motor coordination deficits roughly equivalent to those in patients suffering from EA2. Moreover, it has also been shown that both types of mice exhibit irregular Purkinje cell spike firing, suggesting abnormalities in cerebellar cortical output. Taken together, these facts strongly point to a role of suboptimal SK2 channel activity in EA2. Recent evidence suggests that large-conductance voltage- and calcium-activated BK-type potassium channels are also essential for proper motor coordination (32), but BK channels will not be discussed in detail in this review.

While the involvement of SK2 channels points to a role of spike firing precision and regularity in motor coordination, it also suggests that adaptive plasticity might play a part in ataxia after all. A recent study on hippocampal plasticity has implicated SK2 channels as important for hippocampal LTP as well as hippocampus-dependent forms of learning and memory (33). By using mice overexpressing SK2 channels, this study depicted SK2 channels as a ‘gatekeeper’ to the induction of LTP, with SK2-overexpressing mice exhibiting a higher threshold for LTP induction than wild-type controls. These mice were also deficient in spatial learning and performed poorly in fear-conditioning tasks, reinforcing the importance of neural plasticity for the modification of behavior. SK2 channel blockade enhances spine calcium signaling in CA1 pyramidal neurons (34), resulting in a higher probability of LTP induction (35). In cerebellar Purkinje cells, SK2 channels might play an equally important role in synaptic plasticity. PF tetanization or repeated injection of depolarizing currents enhances the intrinsic excitability of Purkinje cells. This form of intrinsic plasticity is at least partially mediated by a down-regulation of SK2 channel function, which enhances spine calcium signaling but in the cerebellum lowers the probability of LTP induction (36). It remains possible that this form of intrinsic plasticity is crucial for proper motor coordination, directly through its effect on Purkinje cell spike firing, or indirectly through its effect on LTP.

Concluding remarks

In this paper we addressed the question of whether cerebellar ataxias can result from impaired synaptic plasticity processes, such as LTD at PF-Purkinje cell synapses. LTD, and its counterpart, LTP, have been described as fast, activity-dependent mechanisms of controlling synaptic efficacy. It thus appears conceivable that one of the most prominent tasks of the cerebellum, the fine adjustment of motor coordination, requires intact LTD and LTP processes. In line with these considerations, mutant mice with LTD deficits show impaired motor learning, as assessed in motor learning tasks such as associative eyeblink conditioning or VOR gain conditioning. However, basic motor performance is unaffected in some of these mouse models, suggesting that LTD is not strictly required to develop normal motor performance. Recent studies show that EA2, in which P/Q-type calcium channels are affected, results from suboptimal activation of calcium-sensitive SK2 potassium channels. These channels are key players in the control of Purkinje cell excitability and spike firing precision, suggesting that ataxia might result from irregular spike output. At the same time, SK2 channels control spine calcium signaling and synaptic plasticity. Thus, while fast synaptic plasticity mechanisms do not seem to be needed to acquire general motor skills, it remains possible that they play a role in specific aspects of fine adjustment. The observation that motor learning is impaired in LTD/LTP-deficient mice suggests that one important function of synaptic plasticity is to allow for fast adaptation of motor output gains in response to system perturbations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Q. He, C. Piochon and G. Ohtsuki for invaluable discussions that have formed the basis for this review. This work was made possible by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant NS62771 to C.H.

References

- 1.De Zeeuw CI, Yeo CH. Time and tide in cerebellar memory formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jörntell H, Hansel C. Synaptic memories upside down: bidirectional plasticity at cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron. 2006;52:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito M. Cerebellar long-term depression: characterization, signal transduction, and functional roles. Physiol Rev. 2001;3:1143–1195. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lev-Ram V, Wong ST, Storm DR, Tsien RY. A new form of cerebellar long-term potentiation is postsynaptic and depends on nitric oxide but not cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8389–8393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122206399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coesmans M, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. Bidirectional parallel fiber plasticity in the cerebellum under climbing fiber control. Neuron. 2004;44:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansel C, de Jeu M, Belmeguenai A, et al. alphaCaMKII is essential for cerebellar LTD and motor learning. Neuron. 2006;51:835–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belmeguenai A, Hansel C. A role for protein phosphatases 1, 2A, and 2B in cerebellar long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10768–10772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2876-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schonewille M, Belmeguenai A, Koekkoek SK, et al. Purkinje cell-specific knockout of the protein phosphatase PP2B impairs potentiation and cerebellar motor learning. Neuron. 2010;67:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Angelo E, De Zeeuw CI. Timing and plasticity in the cerebellum: focus on the granular layer. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manto MU. The wide spectrum of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) Cerebellum. 2005;4:2–6. doi: 10.1080/14734220510007914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matilla-Dueñas A, Sánchez I, Corral-Juan M, Dávalos A, Alvarez R, Latorre P. Cellular and molecular pathways triggering neurodegeneration in the spinocerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum. 2010;9:148–166. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watase K, Barrett CF, Miyazaki T, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 knockin mice develop a progressive neuronal dysfunction with age-dependent accumulation of mutant CaV2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804350105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell. 1996;87:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llinás RR, Sugimori M, Cherksey B. Voltage-dependent calcium conductances in mammalian neurons. The P channel. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;560:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb24084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintz IM, Venema VJ, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Bean BP, Adams ME. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin omega-Aga-IVA. Nature. 1992;355:827–829. doi: 10.1038/355827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoebeek FE, Stahl JS, van Alphen AM, et al. Increased noise level of Purkinje cell activities minimizes impact of their modulation during sensorimotor control. Neuron. 2005;45:953–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llinás RR, Sugimori M, Lin JW, Cherksey B. Blocking and isolation of a calcium channel from neurons in mammals and cephalopods utilizing a toxin fraction (FTX) from funnel-web spider poison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1689–1693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe S, Takagi H, Miyasho T, et al. Different roles of two types of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the dendrites of rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Brain Res. 1998;791:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmolesky MT, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. The making of a complex spike: ionic composition and plasticity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;978:359–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb07581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han VZ, Zhang Y, Bell CC, Hansel C. Synaptic plasticity and calcium signaling in Purkinje cells of the central cerebellar lobes of mormyrid fish. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13499–13512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2613-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jun K, Piedras-Rentería ES, Smith SM, et al. Ablation of P/Q-type Ca(2+) channel currents, altered synaptic transmission, and progressive ataxia in mice lacking the alpha1A-subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15245–15250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katoh A, Jindal JA, Raymond JL. Motor deficits in homozygous and heterozygous P/Q-type calcium channel mutants. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1280–1287. doi: 10.1152/jn.00322.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aiba A, Kano M, Chen C, et al. Deficient cerebellar long-term depression and impaired motor learning in mGluR1 mutant mice. Cell. 1994;79:377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C, Bian F, et al. Expression of a protein kinase C inhibitor in Purkinje cells blocks cerebellar LTD and adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Neuron. 1998;20:495–508. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feil R, Hartmann J, Luo C, et al. Impairment of LTD and cerebellar learning by Purkinje cell-specific ablation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:295–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Woerden GM, Hoebeek FE, Gao Z, et al. betaCaMKII controls the direction of plasticity at parallel fiber – Purkinje cell synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:823–825. doi: 10.1038/nn.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Alphen AM, De Zeeuw CI. Cerebellar LTD facilitates but is not essential for long-term adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:486–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Womack MD, Khodakhah K. Somatic and dendritic small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels regulate the output of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2600–2607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02600.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Womack MD, Chevez C, Khodakhah K. Calcium-activated potassium channels are selectively coupled to P/Q-type channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8818–8822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2915-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter JT, Alviña K, Womack MD, Chevez C, Khodakhah K. Decreases in the precision of Purkinje cell pacemaking cause cerebellar dysfunction and ataxia. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:389–396. doi: 10.1038/nn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alviña K, Khodakhah K. KCa channels as therapeutic targets in episodic ataxia type-2. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7249–7257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6341-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Kovalchuk Y, Adelsberger H, et al. Disruption of the olivo-cerebellar circuit by Purkinje neuron-specific ablation of BK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12323–12328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001745107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond RS, Bond CT, Strassmaier T, et al. Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel type 2 (SK2) modulates hippocampal learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1844–1853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4106-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ngo-Anh TJ, Bloodgood BL, Lin M, Sabatini BL, Maylie J, Adelman JP. SK channels and NMDA receptors form a Ca2+-mediated feedback loop in dendritic spines. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nn1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stackman RW, Hammond RS, Linardatos E, et al. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels modulate synaptic plasticity and memory encoding. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10163–10171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10163.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belmeguenai A, Hosy E, Bengtsson F, et al. Intrinsic plasticity complements LTP in parallel fiber input gain control in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13630–13643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3226-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]