Abstract

We examined whether adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet has positive effects on mobility assessed over a nine-year follow-up in a representative sample of older adults. This research is part of the InCHIANTI Study, a prospective population-based study of older persons in Tuscany, Italy. The sample for this analysis included 935 women and men aged 65 years and older. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was assessed at baseline by the standard 10-unit Mediterranean diet score (MDS). Lower extremity function was measured at baseline, and at the 3, 6 and 9-year follow-up visits using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). At baseline, higher adherence to Mediterranean diet was associated with better lower body performance. Participants with higher adherence experienced less decline in SPPB score, which was of 0.9 points higher (p<.0001) at the 3-year-follow, 1.1 points higher (p= 0.0004) at the 6-year follow-up and 0.9 points higher (p= 0.04) at the 9-year follow-up compared to those with lower adherence. Among participants free of mobility disability at baseline, those with higher adherence had a lower risk (HR=0.71,95%CI=0.51–0.98, p=0.04) of developing new mobility disability. High adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is associated with a slower decline of mobility over time in community dwelling older persons. If replicated, this observation is highly relevant in terms of public health.

Keywords: Mediterranean diet, mobility, SPPB, aging

INTRODUCTION

The traditional diet of populations living in the Mediterranean area is widely considered a model of healthy eating [1,2]. The Mediterranean diet is characterized by high intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits and nuts, cereals and olive oil with low intake of saturated fat, moderately high intake of fish, low-to-moderate intake of dairy products, low intake of meat, and a regular but moderate intake of alcohol primarily in the form of wine during meals [3]. Epidemiological studies conducted in different countries have shown that adherence to a Mediterranean type diet is associated with longer survival, lower risk of cognitive decline, chronic degenerative disease, depression, and reduced cardiovascular and cancer mortality [3–9]. However, whether adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is associated with less decline of physical function in aging individuals has not been investigated. Testing this hypothesis is important to build the foundation for the development of nutritional interventions aimed at promoting healthy aging. In this study we examined the longitudinal relationship between adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet and lower extremity performance over a nine-year follow-up in a representative sample of community-dwelling older Italians. We hypothesized that higher adherence to Mediterranean diet would be associated with slower decline of lower extremity performance and lower risk of developing mobility disability.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study Population

This study is based on data collected in the InCHIANTI (Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti area) study, a prospective population-based study of older persons in Tuscany (Italy) designed to investigate factors contributing to decline of mobility in late life. A description of the study rationale, design and methods is given elsewhere [10]. Briefly, in 1998–1999 a sample was randomly selected from two sites, Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli, using a multistage stratified sampling method: 1270 persons ≥65 years were randomly selected from the population registry of the two sites, another 29 subjects ≥90 years were oversampled. Thirty-nine participants were not eligible because they had already died or emigrated. Among those who were eligible, 1155 (91.6%) were enrolled. The participation rate increased with age up to the age of 85 and in each age group was higher in women than in men. However, there was a drop in participation in the oldest-old age group (men: 77.1%; women: 78.4%). Data collection included: 1) a home interview concerning demographics, health-related behaviors, functional status, cognitive function and a food-frequencies questionnaire; 2) a medical examination including several performance-based tests of physical function conducted in the study clinic; 3) 24-h urine collection and blood drawing. Participants were invited again to a three-year follow-up visit (2001–2003), six-year follow-up visit (2004–2006) and nine-year (2007–2009) follow-up visit.

Of the 1155 participants aged ≥65 enrolled in the study, we excluded 159 because of missing data on dietary intake or physical performance at baseline. Moreover, 61 participants with dementia were also excluded. In cross-sectional analyses we included all 935 remaining participants. Among these, 705 participants had available data on lower body mobility at 3-year follow-up, 614 at 6-year follow-up and 486 at 9-year follow-up. Over the course of the study, 247 participants died, and 10 were lost to follow-up. Participants who did not take part in any of the follow-ups, as compared to participants who participated in at least at one follow-up, were significantly older, more likely to be disabled, reported more chronic diseases, had poorer cognitive function and lower extremity performance.

All respondents signed informed consent and the Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee approved the study protocol.

Mediterranean Diet Score

Daily dietary intake was assessed at baseline by the food-frequency questionnaire created for the European Prospective Investigation on Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study, previously validated in the InCHIANTI population [11]. The Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS) was computed according to the method developed by Trichopoulou et. al [3]. Intake of each of 9 food groups was dichotomized using sex-specific median values as cut-offs. A score of 1 was assigned for above the median level of presumed beneficial foods (vegetables, legumes, fruits, cereal, fish and ratio of monounsaturated fats to saturated fats) and consumptions below the median level of presumed detrimental foods (meat and dairy products). For ethanol, 1 point was assigned to men who consumed between 10 and 50 g per day and to women who consumed between 5 and 25 g per day. Thus, the total MDS ranged from 0 (minimal adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet) to 9 (maximal adherence). For analytical purposes, we also categorized the MDS into approximate tertiles as follows: low adherence (MDS ≤ 3), medium adherence (MDS 4–5) and high adherence (MDS ≥ 6).

Physical performance

Lower body performance was assessed at baseline and at 3-, 6- and 9-year follow-up with the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [12], which was derived from three objective tests of physical function: 4-meter walking speed, repeated chair rises and standing balance in progressively more challenging positions. Walking speed was defined as the better performance (time) of 2 walks at usual pace over a 4-meter course. For the chair-stand test, participants were asked to rise 5 times from a seated position as quickly as possible with their hands folded across the chest, and performance was expressed as total time to complete the test. For the standing balance tests, participants were asked to stand in 3 progressively more difficult positions for 10 seconds each: feet in side-by-side, semitandem and full tandem positions. Each test was scored 0 to 4 as per previously determined criteria [13] with a value of 0 indicating the inability to complete the test and 4 the highest level of performance. Scores from the three tests were summed into a composite score ranging 0 to 12, higher scores reflect better physical function. The SPPB has excellent reliability and is a strong predictor of nursing home admission, disability in self-care tasks and mobility, and death among older adults [12,13]. The SPPB is highly sensitive and the loss of 1 point is considered a clinically meaningful change [14]. Previous studies indicated that an SPPB cut point of less than 10 identifies individuals at increased risk of mobility disability [15]. Therefore, the development of “mobility disability” was defined as an SPPB score below 10 points.

Covariates

The following covariates assessed at baseline were used in the analysis: age, gender, education (years), smoking habit (current/former/non-smoker), Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, body mass index (BMI), number of prescribed and non-prescribed drugs. Level of physical activity in the previous 12 months was classified as sedentary (completely inactive or light physical activity: ie, walking), light (light physical activity for 2 to 4 h/wk), and moderate to intense (light physical activity for more then 4 h/wk or moderate physical activity (ie, swimming etc) [16]. Number of activities of daily living (ADL) (0–6) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (0–8) disabilities was defined as self-report of inability or needing personal help in performing any basic or instrumental activities of daily living [17]. Total number of chronic diseases (heart failure, coronary heart disease including angina and myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive lung disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson’s disease and hip arthritis) was calculated as a global marker of poor physical health; diseases were ascertained according to standardized, pre-established criteria and algorithms based upon those used in the Women’s Health and Aging Study [18] using information on self-reported history, pharmacological treatments, medical exam data and hospital discharge records. Energy intake was collected by the food-frequency EPIC questionnaire [11]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [19]. A score ≥20 was operationally defined as clinically relevant “depressed mood” [20]. Knee extension, assessed by using a handheld dynamometer and a standard protocol [21] was considered to indicate lower extremity muscle stenght. Previously from the InCHIANTI Study, Lauretani et al. [22] reported that participants with lower plasma carotenoids, a reliable index of fruit and vegetables intake, had higher decline over time of knee extension.

Statistical Analyses

Variables were reported as percentage or means±SD as appropriate. Logistic regression analyses were used to measure the association between MDS and mobility disability at baseline, adjusting progressively for all confounders significantly associated with MDS. To examine the longitudinal association of baseline MDS with SPPB scores while accounting for correlation of repeated SPPB measures, regression models were fitted using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an unstructured covariance [23]. Appropriate MDS-by-time interaction terms were included in the model to compare rates of change in SPPB scores at each follow-up point between participants with different baseline MDS. Covariates were selected that in the literature have been associated with dietary intake and that were significantly associated with MDS at baseline. From the initial fully adjusted models, we derived parsimonious models adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, BMI and confounders that significantly and independently contributed to the model fit. This analysis was repeated using mixed models analyses with an unstructured covariance; all variables were entered in the model as fixed factors, the only random factor entered in the model was the subject. Next, multivariate Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare risk of developing mobility disability over the follow-up period associated with different MDS groups in a subset of participants with no ADL disabilities and SPPB≥10 at enrollment. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by including a time-to-event by MDS interaction term. Those surviving without developing mobility disability were censored at the date of the last follow-up; those dying without their SPPB dropping below 10 points were censored at the time of their death. Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were used to compare MDS groups. Multivariate models were additionally adjusted for baseline SPPB in order to correct for the “regression to the mean”. Finally, analyses were repeated including the adjustment for knee extension. This adjustment was not included in previous analyses in order to avoid overadjustment, defined as the control for an intermediate variable (or a descending proxy for an intermediate variable) on a causal path from exposure to outcome [24]. All analyses were performed using SAS (v. 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) with a statistical significance level set at P <0.05.

RESULTS

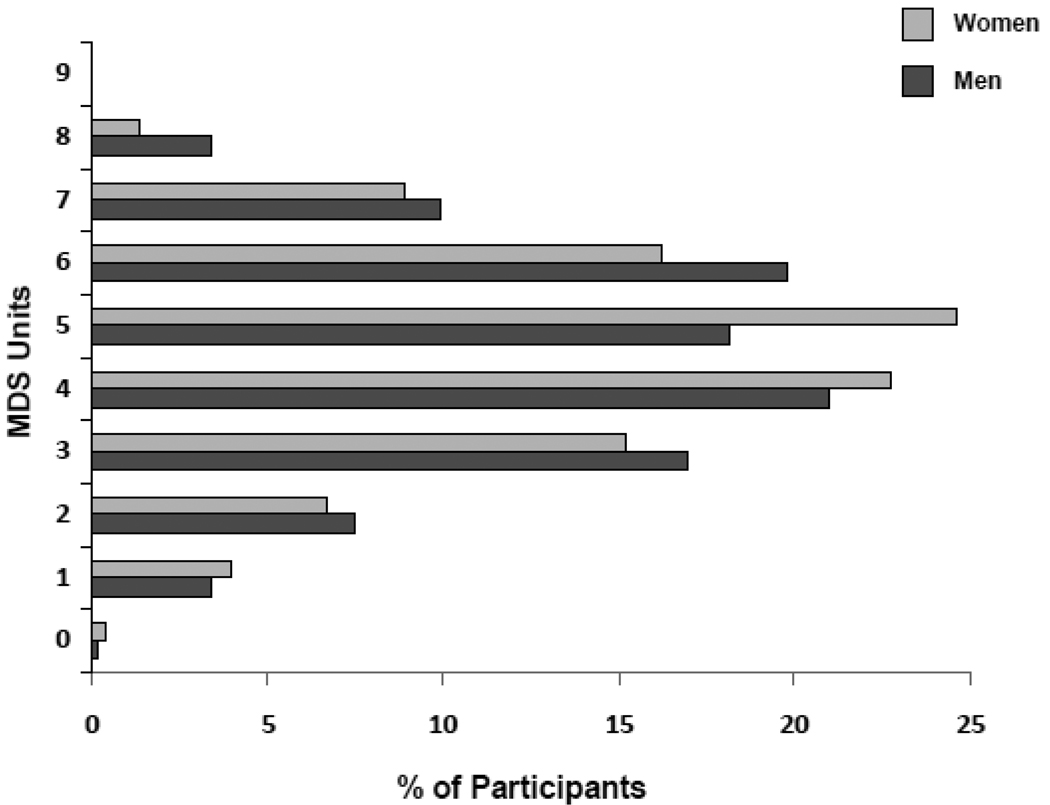

Participants mean (±standard deviation, SD) age of at baseline was 74.1 (±6.8) years and 55.6% were women. Figure 1 shows the distributions of 935 participants at enrollment, according to sex and MDS scores. Of these, 27.1% showed low adherence (MDS ≤ 3) to the Mediterranean diet, 43.6% medium adherence (MDS 4–5) to this diet and 29.3% high adherence (MDS ≥ 6) to this diet. No participants obtained a score of 9, indicating maximal adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Table 1 describes the characteristics of participants for the total baseline sample and according to MDS subgroups: low adherence (MDS ≤ 3), medium adherence (MDS 4–5) and high adherence (MDS ≥ 6). Participants with low adherence were older, had a higher number of chronic diseases, took more medications, were more likely to be women, disabled, depressed and sedentary, had lower SPPB and MMSE scores, had lower energy dietary intake and knee strenght. Adjusted Odds Ratios (OR) for the association between MDS and mobility disability at baseline are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for age, sex, energy intake and BMI, participants with high adherence, as compared to those with low adherence, were less likely to have mobility disability at baseline (OR=0.50,95%CI=0.30–0.82, p=0.006). After full adjustment, participants highly adherent still had a lower probability of having mobility disability, although not significant. Consistent findings were obtained with continuous MDS (Table 2); round number close to the SD (1.6 points) were used as increments in the regression models.

Figure 1.

MDS score distribution in women (n = 520) and (n = 415) men.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at baseline according to Mediterranean Diet Score.

| Mediterranean Diet Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n=935) |

≤ 3 (n=253) |

4 – 5 (n=408) |

≥ 6 (n=274) |

||

| Characteristics | p* | ||||

| Age (years) | 74.1±6.8 | 76.3±7.4 | 73.9±6.8 | 72.5±5.8 | <.0001 |

| Sex (F) | 55.6 | 54.2 | 60.3 | 50.0 | 0.03 |

| Education (years) | 5.5±3.3 | 5.3±3.5 | 5.4±3.2 | 5.7±3.2 | 0.3 |

| Smoking status | 0.86 | ||||

| non smoker | 58.9 | 58.5 | 60.3 | 57.3 | |

| former smoker | 27.2 | 26.1 | 26.7 | 28.8 | |

| current smoker | 13.9 | 15.4 | 13.0 | 13.9 | |

| MMSE scores | 25.4±3.1 | 24.9±3.3 | 25.4±3.1 | 25.8±2.9 | 0.002 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.5±4.1 | 27.1±4.4 | 27.5±4.1 | 27.9±3.8 | 0.06 |

| Physical activity | <.0001 | ||||

| Low | 17.4 | 26.5 | 15.4 | 12.0 | |

| Medium | 76.8 | 70.8 | 78.2 | 80.3 | |

| High | 5.8 | 2.8 | 6.4 | 7.7 | |

| Depressed mood | 20 | 27.8 | 19.6 | 13.6 | 0.0002 |

| No. of ADL disabilities | 0.1±0.6 | 0.5±1.4 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.1±0.6 | <.0001 |

| No. of IADL disabilities | 0.6±1.6 | 0.3±0.9 | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.4 | <.0001 |

| No. of medications | 2.2±2.0 | 2.7±2.2 | 2.2±1.9 | 1.9±1.9 | <.0001 |

| No. of chronic diseases | 1.2±0.9 | 1.4±1.1 | 1.2±0.9 | 1.1±0.8 | 0.0003 |

| SPPB score | 10.1±2.9 | 9.3±3.5 | 10.1±2.7 | 10.8±2.1 | <.0001 |

| Energy intake (Kcal/day) | 1932.2±560.9 | 1807.6±579.9 | 1915.1±559.4 | 2072.5±514.5 | <.0001 |

| Knee strenght (Kg) | 16.0±6.0 | 15.1±6.1 | 15.9±6.0 | 17.0±5.9 | 0.001 |

Variables reported as percentage or means±standard deviation as appropriate

Based on chi-square or general linear model as appropriate.

MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; BMI, Body Mass Index; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Depressed mood: CES-D score ≥ 20.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Mobility Disability according to Mediterranean Diet Score baseline.

| Mobility Disability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 935 | Model 1* | Model 2† | Model 3‡ | ||||||

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | O.R. | 95% C.I. | P | |

| MDS | |||||||||

| Low adherence | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Medium adherence | 0.70 | (0.47 – 1.05) | 0.09 | 0.73 | (0.48 – 1.10) | 0.13 | 0.97 | (0.60 – 1.57) | 0.9 |

| High adherence | 0.47 | (0.29 – 0.76) | 0.002 | 0.50 | (0.30 – 0.82) | 0.006 | 0.73 | (0.41 – 1.28) | 0.27 |

| Per 2-point increase | 0.75 | (0.61 – 0.92) | 0.005 | 0.78 | (0.63 – 0.96) | 0.02 | 0.92 | (0.73 – 1.17) | 0.49 |

Adjusted for age and sex

Adjusted for age, sex, energy intake and BMI.

Adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, ADL and IADL disabilities, depressed mood, number of chronic diseases and medicattions

O.R. Odds Ratio; C.I., Confidence Interval

MDS, Mediterranean Diet Score: low adherence ≤ 3; medium adherence 4 – 5; high adherence ≥ 6; SD = 1.6 points

Mobility Disability: SPPB ≤ 9.

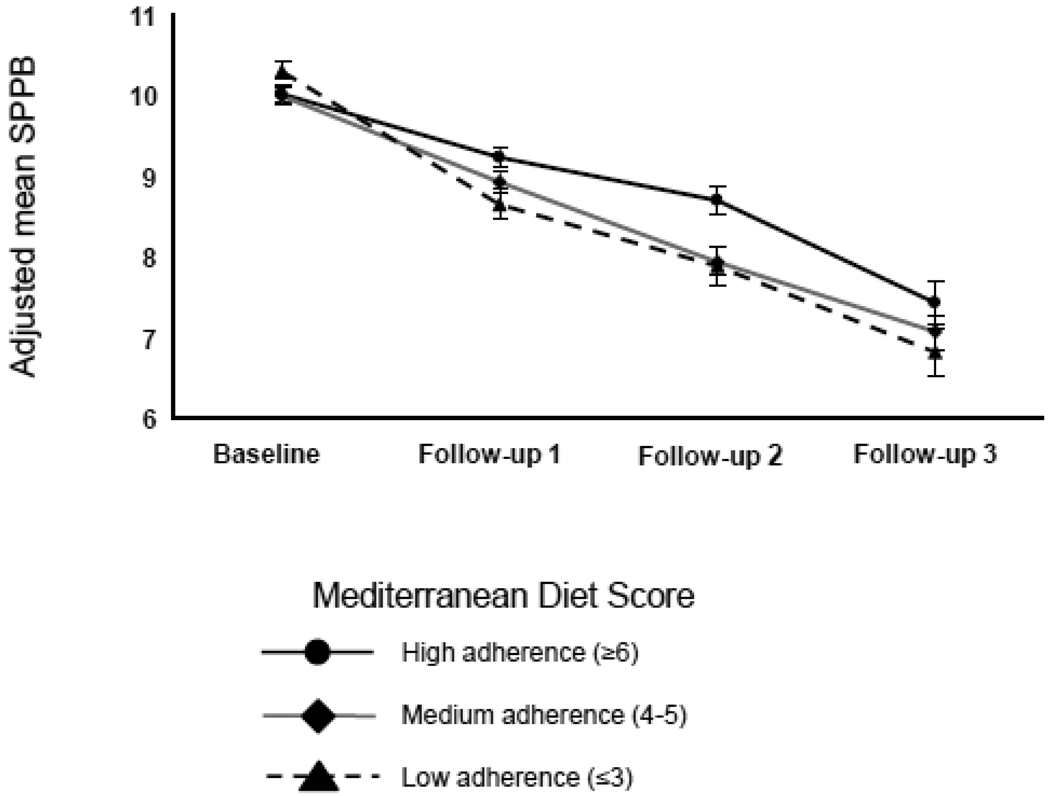

A GEE model adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, ADL and IADL disabilities, depressed mood and number of chronic diseases, was fit in order to compare how SPPB scores changed over time across baseline MDS groups. As shown in Figure 2, participants with higher adherence experienced a significantly smaller decrease in SPPB scores over time. Specifically, participants with MDS score 6–9 had average change in SPPB scores of 0.9 points higher (SE=0.2, p<.0001) at 3-year-follow, 1.1 point higher (SE=0.3, p= 0.0002) at 6-year follow-up and 0.9 points higher (SE=0.4, p= 0.03) at 9-year follow-up (Table 3) compared to those with MDS score 1–3. Difference in average SPPB scores between participants with medium adherence and those with low adherence was statistically significant only at 3-year follow-up by 0.6 points (SE=0.2, p= 0.01). These findings were confirmed by mixed models analyses with substantially the same results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) scores during 9 years of follow-up by baseline Mediterranean Diet Score groups. Estimated Means and Standard Errors are adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, ADL and IADL disabilities, depressed mood and number of chronic diseases.

Table 3.

GEE model estimates of lower extremity performance over 9 years follow-up in InCHIANTI participants according to baseline Mediterranean Diet Score.

| Estimate | S.E. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction: Diet × Time | |||

| Low adherence × T1 | Ref | ||

| Medium adherence × T1 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| High adherence × T1 | 0.86 | 0.21 | <.0001 |

| Low adherence × T2 | Ref | ||

| Medium adherence × T2 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| High adherence × T2 | 1.09 | 0.29 | 0.0002 |

| Low adherence × T3 | Ref | ||

| Medium adherence × T3 | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.14 |

| High adherence × T3 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 0.03 |

Adjusted for age, sex, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, ADL and IADL disabilities, depressed mood and number of chronic diseases.

Mediterranean Diet Score: low adherence ≤ 3; medium adherence 4 – 5; high adherence ≥ 6.

Among non-disabled participants with SPPB score ≥10 at baseline, higher adherence to Mediterranean diet at baseline was also a significant predictor of lower probability of developing mobility disability over the follow-up (Table 4). Of these 684 highly functioning participants, 272 (39.8%) developed mobility disability over the follow-up period. The proportional hazard assumption was met in all analyses (non significant time-to-event by MDS interaction term). After adjustment for age, sex, baseline SPPB, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, IADL disabilities, depressed mood and number of chronic diseases, participants with high adherence, as compared to those with low adherence, had a lower risk (HR=0.71,95%CI=0.51–0.98, p=0.04) of developing mobility disability. Moreover, a 2-point increase in MDS was associated with a 14% lower risk of mobility disability over time (Table 4). In previous analyses we did not include knee strenght because this variable may be considered to be in the causal pathway between poor dietary intake and lower extremity perfromance [22,24]. However, when knee strenght was included in the final model, in addition to the variables in model 2 (Table 4), higher adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet (per 2 MDS points increase) was still associated with a lower risk (HR=0.86,95%CI=0.74–0.99, p =0.04) of developing mobility disability.

Table 4.

Adjusted Incidence of Mobility Disability according to baseline Mediterranean Diet Score in participants without ADL disabilities and SPBB ≥ 10.

| Mobility Disability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 684 | Model 1* | Model 2† | ||||

| H.R. | 95% C.I. | P | H.R. | 95% C.I. | P | |

| Mediterranean Diet Score | ||||||

| Low adherence | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Medium adherence | 0.79 | (0.58 – 1.06) | 0.11 | 0.78 | (0.58 – 1.07) | 0.12 |

| High adherence | 0.69 | (0.50 – 0.96) | 0.03 | 0.71 | (0.51 – 0.98) | 0.04 |

| Per 2 points increase | 0.85 | (0.74 – 0.98) | 0.03 | 0.86 | (0.74 – 0.99) | 0.04 |

Adjusted for age, sex and baseline SPPB.

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline SPPB, energy intake, BMI, MMSE score, physical activity, IADL disabilities, depressed mood and number of chronic diseases.

H.R. Hazard Ratio; C.I., Confidence Interval.

Mediterranean Diet Score: low adherence ≤ 3; medium adherence 4 – 5; high adherence ≥ 6; SD = 1.6 points

Mobility Disability: SPPB ≤ 9.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a population-based study of older persons in Italy, we found evidence of a prospective association between adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet and mobility. Participants highly adherent to Mediterranean diet had slower decline in lower body physical performance over nine years of follow-up and had lower risk of developing mobility disability.

Previous studies in older persons established a beneficial role for a Mediterranean diet type in preventing cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders, and promoting quality of life and overall survival [2]. To our knowledge, this is the first study directly examining the relationship between Mediterranean diet and decline of lower body mobility in older adults.

Mediterranean diet could influence physical function decline in several ways. Adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is associated with adequate intake of certain nutrients, such as vitamins and other antioxidants, which have been related to a reduced risk of physical function impairment in older persons. Previous studies have shown that that low levels of intake and low serum concentrations of vitamin E are associated with reduced physical performance, frailty and disability [25–27]. Moreover, lower plasma levels of carotenoids have been shown to be associated with poor skeletal muscle strength [22]. High plasma concentrations of carotenoids have also been found to be protective against decline in walking speed and the development of severe walking disability [28–30]. Antioxidants play an important role in counterbalancing the age-dependent increase in oxidative stress through the quenching of hydroxyl radicals and reduction in lipid peroxidation [31]. If the amount of free radicals generated exceeds the antioxidant potential capacity, this imbalance may cause oxidative damage to DNA, protein, and lipids in skeletal muscle, leading to atrophy and loss of muscle fibers [31]. Moreover, antioxidants such as carotenoids have been shown to modulate activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) a major transcriptional factor involved in the up-regulation of interleukin-6 [32]. Therefore, low levels of these nutrients are independent predictors of subsequent increase in the inflammatory response, which, in turn, is associated with an increased risk of reduced physical function [33]. Recent trials showed that nutritional interventions based on Mediterranean diet significantly reduced the levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and C reactive protein [34,35].

A major strength of this study is the longitudinal design and the use of a standardized, objective battery of physical performance tests for lower extremity function (SPPB), which is probably less biased by personality, mood and cognition than self-report measures. Moreover, adherence to Mediterranean diet was evaluated by a score which has been widely used and validated [3]. A limitation of this study is the loss of participants to follow-up. Participants who were lost to follow-up were significantly older, more disabled, had more chronic diseases and poorer cognitive function compared to those who participated in at least one follow-up; this could limit the generalization of the findings. However, participants lost to follow-up also had significantly lower physical performance. Therefore, censoring of these participants would likely underestimate the strength of the relationship between adherence to this dietary pattern and lower extremity performance. Moreover, the relationship under study has many potential important confounders: participants with low adherence to a Mediterranean diet had more chronic diseases and disabilities, conditions that could determine a lower adherence to a healthy dietary pattern. However, the association between Mediterranean diet and change in physical function remained significant after the selection of a subset of participants with no disabilities and a SPPB scores ≥ 10, a measure that identifies healthy and highly functioning persons.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides evidence that a high adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet is associated with a slower decline in lower body mobility over time in older persons living in the community. Confirmation of this finding in other studies and adequately sized clinical trials are needed to definitively determine whether a nutritional intervention that follow a Mediterranean diet can reduce functional decline and the onset of disability in older persons. Dietary interventions may be a cost-effective strategy to promote healthy aging and reduce the burden of age-related disability in the population.

Mediterranean diet is widely considered a model of healthy eating

-

➢

Adherence to Mediterranean is associated with lower decline in mobility over time.

-

➢

Adherence to Mediterranean is associated with lower risk of mobility disability.

Acknowledgment

“The InCHIANTI study baseline (1998–2000) was supported as a “targeted project” (ICS110.1/RF97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health and in part by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts: 263 MD 9164 and 263 MD 821336); the InCHIANTI Follow-up 1 (2001–2003) was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts: N.1-AG-1-1 and N.1-AG-1-2111); the InCHIANTI Follow-ups 2 and 3 studies (2004–2010) were financed by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contract: N01-AG-5-0002);supported in part by the Intramural research program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: All the authors took part in every aspect of this paper including the design, preparation of the manuscript and writing of this paper.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman B, Carta L, Martínez-González MA, Serra-Majem L. Effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(1):97–109. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoops KT, de Groot LC, Kromhout D, Perrin AE, Moreiras-Varela O, Menotti A, van Staveren WA. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1433–1439. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Mediterranean diet and survival among patients with coronary heart disease in Greece. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(8):929–935. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benetou V, Trichopoulou A, Orfanos P, Naska A, Lagiou P, Boffetta P, Trichopoulos D Greek EPIC cohort. Conformity to traditional Mediterranean diet and cancer incidence: the Greek EPIC cohort. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(1):191–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-González MA, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Beunza JJ, Vazquez Z, Benito S, Tortosa A, Bes-Rastrollo M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7657):1348–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39561.501007.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Féart C, Samieri C, Rondeau V, Amieva H, Portet F, Dartigues JF, Scarmeas N, Barberger-Gateau P. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet, cognitive decline, and risk of dementia. JAMA. 2009;302(6):638–648. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Serra Majem L, Martínez-González MA. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090–1098. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, Di Iorio A, Macchi C, Harris TB, Guralnik JM for the InCHIANTI Group. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisani P, Faggiano F, Krogh V, Palli D, Vineis P, Berrino F. Relative validity and reproducibility of a food frequency dietary questionnaire for use in the Italian EPIC centres. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26 Suppl 1:S152–S160. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasunilashorn S, Coppin AK, Patel KV, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM. Use of the Short Physical Performance Battery Score to Predict Loss of Ability to Walk 400 Meters: Analysis From the InCHIANTI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:223–229. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger RS., Jr Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Kasper D, Lafferty ME. The Women’s Health and Aging Study: health and social characteristics of older women with disability. Bethesda: National Institute on Aging. 1995 NIH Publication No.95-4009.

- 19.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27:231–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, Del Lungo I, Baccini M, Benvenuti F, Di Iorio A, Ferrucci L. Measuring muscular strength of the lower limbs by hand-held dynamometer: a standard protocol. Aging. 1999 Oct;11(5):287–293. doi: 10.1007/BF03339802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauretani F, Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Dayhoff-Brannigan M, Giacomini V, Corsi AM, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Low plasma carotenoids and skeletal muscle strength decline over 6 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(4):376–383. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twisk JW. Longitudinal data analysis. A comparison between generalized estimating equations and random coefficient analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:769–776. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036572.00663.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20:488–495. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartali B, Frongillo EA, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Semba RD, Fried LP, Ferrucci L. Low nutrient intake is an essential component of frailty in older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(6):589–593. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cesari M, Pahor M, Bartali B, Cherubini A, Penninx BW, Williams GR, Atkinson H, Martin A, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Antioxidants and physical performance in elderly persons: the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(2):289–294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartali B, Frongillo EA, Guralnik JM, Stipanuk MH, Allore HG, Cherubini A, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L, Gill TM. Serum micronutrient concentrations and decline in physical function among older persons. JAMA. 2008;299(3):308–315. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauretani F, Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Dayhoff-Brannigan M, Lauretani F, Corsi AM, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Carotenoids as protection against disability in older persons. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11(3):557–563. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semba RD, Varadhan R, Bartali B, Ferrucci L, Ricks MO, Blaum C, Fried LP. Low serum carotenoids and development of severe walking disability among older women living in the community: the women's health and aging study I. Age Ageing. 2007;36(1):62–67. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayne ST. Antioxidant nutrients and chronic disease: use of biomarkers of exposure and oxidative stress status in epidemiologic research. J Nutr. 2003;133 Suppl 3:933S–940S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.933S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mecocci P, Fanó G, Fulle S, MacGarvey U, Shinobu L, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Vecchiet J, Senin U, Beal MF. Age-dependent increases in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins in human skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(3–4):303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Pahor M, Lauretani F, Corsi AM, Rhys Williams G, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Inflammatory markers and physical performance in older persons: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):242–248. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, Di Palo C, Giugliano F, Giugliano G, D'Armiento M, D'Andrea F, Giugliano D. Effect of a mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Covas MI, Fiol M, Gómez-Gracia E, López-Sabater MC, Vinyoles E, Arós F, Conde M, Lahoz C, Lapetra J, Sáez G, Ros E PREDIMED Study Investigators. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):1–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]