Abstract

Background:

Reported cases of nearly 2600 children (subjects) who claim to remember previous lives have been investigated in cultures with and without belief in reincarnation. The authenticity in most cases has been established.

Aims:

To study the influence of attitudes of parents of the subjects, families of the deceased person with whom they are identified and attention paid by others on the features of the cases.

Settings and Design:

The study is based on field investigations.

Materials and Methods:

Data is derived from analysis of a larger series of an ongoing project. Information on initial and subsequent attitudes of subjects′ mothers was available for 292 and 136 cases, respectively; attitudes of 227 families of deceased person (previous personality) with whom he is identified, and the extent of attention received from outsiders for 252 cases. Observations and interviews with multiple firsthand informants on both sides of the case as well as some neutral informants supplemented by examination of objective data were the chief methods of investigation.

Results:

The initial attitude of mothers varied from encouragement (21%) to neutral or tolerance (51%) to discouragement (28%). However, it changed significantly from neutrality to taking measures to induce amnesia in their children for previous life memories due to various psychosocial pressures and prevalent beliefs. Families of the previous personalities, once convinced, showed complete acceptance in a majority of cases. Outside attention was received in 58% cases.

Conclusions:

The positive attitude of parents might facilitate expression of memories but subsequently attitudes of persons concerned do not seem to alter features of the cases.

Keywords: Attitudes, past life memories, reincarnation

INTRODUCTION

Small children sometimes say that they lived in different circumstances and families before their present life and provide varying accounts and amounts of details of that life. We refer them as cases of the reincarnation type (CORT). Such cases have been reported from different countries including the Western ones; although more cases have been reported from the Asian countries. Over the past five decades nearly 2600 reported CORT have been investigated in several cultures and a number of reports, highlighting different features of cases, have been published in the scholarly books and scientific journals of repute.[1–11]

A child (subject of the case) who claims to remember a previous life also displays unusual behavioral features corresponding to the actual or expected behavior of the deceased person whose life he claims to remember. For brevity, I shall refer this person, as we customarily do, as the previous personality. I shall do so without using any adjectives such as “claimed” previous personality, or “concerned” previous personality; and for the same reason, the subjects would be referred by the masculine gender throughout the article. The subject usually starts making statements about a previous life between 2 and 4 years of age or soon after he attains speech; some times a child tries to communicate, through gestures, even before he could express himself in words. His statements about the previous life include name of the previous person, persons and places associated with the claimed previous life, his possessions as well as the accounts of mode of death in that life. Subjects generally stop making spontaneous references to the previous lives between the ages of 5 and 8; they rarely continue to talk about that life beyond the age of 10. However their behavioral memories generally continue beyond their imaged memories.

Sometimes a neighbor or a friend who would have heard the child make statements about a previous life would urge the parents of the child to search for the family about whom the child has been making statements or the child himself would insist so much to be taken to the previous family that the parents have to yield to his request. With the details provided by the child, his parents or other relatives try to identify such a deceased person and his family; it facilitates the search if a child has given specific details and enough information about the life remembered. On other occasions, the family members of the previous personality learn about the subject's claims, and approach the family of the subject. The two families concerned thus meet. A deceased person satisfactorily matching the claims of the child could be identified in about 64 to 80 percent of cases across cultures.

It must be added, for the benefit of readers new to the CORT research, that these children develop normally and do not show behavioral or other mental health problems more than reported in the general population. Parents of such children sometimes seek medical assistance for their claims or unusual behavior but for want of knowledge in the area, physicians misdiagnose and prescribe treatment accordingly; which would certainly harm the child than do any good to him.[12] It is therefore important to consider reincarnation as one of the strong interpretations for such cases (for details of other interpretations, see[1,3]); care should also be taken to look for any environmental influences that might affect their features.

An earlier study revealed that parents' knowledge of other cases did not seem to influence features of the CORT; features differed considerably even when the model cases were available within the same villages or even within the same families.[13] It is also important to learn whether or not the attitude of the subject's family, attitude of family of the previous personality, or of the outsiders play any role in the development of a case and/or their influence on the continuation (or cessation) of the child's talk or behavior concerning a previous life. This article attempts to address these questions.

Source of data

Data for the present article is derived from an analysis of a larger series of an on-going project on CORT investigated in India.

Method of investigating cases

The methods employed for the investigation of cases essentially include interviews with multiple first hand informants on both sides of the case, that is, the family of the subject as well as the surviving members and friends of the previous personality. The interviews are usually conducted first with families of the subjects and then with the members of the previous personality; occasionally due to geographical reasons the families of the previous personalities are interviewed first. For example, if the previous family lives closer to the place where we are investigating other cases and the new case merits immediate attention or the address of the subject was not known to the informant or was not provided in the first information about the case. In addition to interviewing informants concerned in the immediate families, neutral informants on both sides who would have been, for example, first-hand witnesses to the statements or to the unusual behaviors of the subjects, or witness to the mode of death of the previous personality are also interviewed. An effort is always made to interview the child if he cooperates and/or make observations of his behavior that might help in evaluating the case. The information is supplemented by various written documents such as horoscopes, records at the municipalities, hospitals and police stations for checking the dates of birth of the subjects and dates of death and circumstances related to the death of the previous personalities etc. We also periodically follow-up these cases to learn about the later development. The detailed methods have been provided elsewhere.[1,3]

Along with other pertinent information about the case, the attitudes of the parents or other significant members of the family of the subjects and those of the surviving members of the previous personality, toward subject's memories of previous life are recorded. In addition, the amount of attention a case receives from outside the two families concerned is also ascertained.

As children mostly remain under the care of their mothers when they start talking about previous lives, mothers′ (or a substitute's) observation and reactions to the child's statements, her initial and subsequent attitudes to the claims of the child are taken into account; attitude of fathers is also recorded when available. However, sufficient data for fathers was not available for the present article. Moreover, an earlier study on a relatively smaller sample showed no significant difference between the attitudes of both parents toward claims of the subjects;[3] therefore, attitude of mothers would suffice for the present article. The reason for variability in N on different features is due to non-availability of information of a particular variable.

RESULTS

Attitude of subjects' mothers

Information regarding mothers′ initial and subsequent attitude toward their children's memories of previous lives was available for 292 and 136 cases, respectively. The attitudes varied from total support through to being tolerant or neutral to complete rejection.

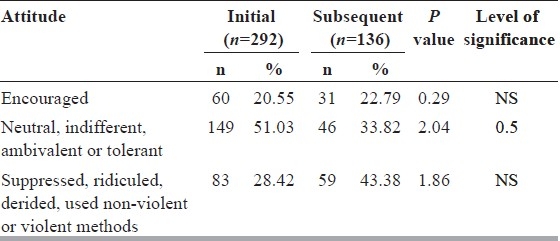

Table 1 shows the initial and subsequent attitudes of the subjects′ mothers to the claims of previous life memories of their children.

Table 1.

Initial and subsequent attitude of mothers

Of the 292 mothers, at initial stages when the children started talking about previous lives, 21% of them encouraged their children to give more details about the previous life, while 28% tried to suppress memories of their children. For suppression the methods used were diverting attention of the child, ridiculing or deriding the child, using non-violent measures, such as rebuking or carrying out certain harmless rituals (for example, light tapping on the head) to violent measures such as spinning the child counter clockwise on a potter's wheel. Twenty-eight percent of the mothers were neutral, tolerant or ambivalent toward the past life memories.

Mothers' attitude subsequent to the development of the case was found to have been changed significantly (P<0.05) from neutrality to taking measures for inducing amnesia for previous life memories. Fifty nine (43%) of them tried to use different methods for this purpose.

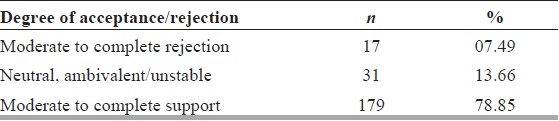

Table 2 shows the results of an analysis of 227 cases on the attitude of previous families to the claims of the subjects.

Table 2.

Acceptance of subjects by previous families (n=227)

As can be seen from Table 2, in a majority (79%) of cases, the families concerned accepted the claims of the subjects; in 31 cases (14%) they were either neutral or ambivalent, while 17 (7%) families rejected the claims.

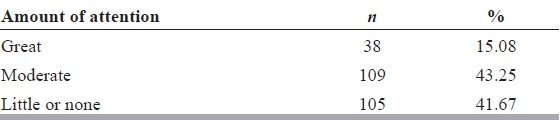

Attention received from outside the subject's and previous personality's families

Table 3 shows the amount of attention received from outside the two families concerned. This included attention from other villagers who thought the subjects had special powers or were special in some other ways, the print media (sometimes) and electronic media (occasionally) also visited some of the cases.

Table 3.

Amount of attention by outsiders (n=252)

DISCUSSION

In the present article three features, namely, initial attitude of subject's mothers at the time of development of the case and subsequently after its development, attitude of the family of previous personality and attention received by the subjects from outside the two families concerned that might influence features of the cases are considered. Initial attitude of the mothers (and/or other members of the family) help in the identification of the deceased person who the child claims to have been, attitude of the previous family helps in validation (or otherwise) of the claims and the attention received from outsiders may either add to the authenticity of the case or embellish it; it might help or hurt a case.

When a child makes statements about his previous life for the first time, some of the mothers encourage the child to give more information to satisfy their curiosity regarding the occurrence of the phenomenon; others even suppress their children's memories. But attitude is neutral or that of tolerance in most cases. However, once the case is solved i.e. the corresponding deceased person has been identified and the two families concerned meet it becomes, after a while, a nuisance for the families particularly the family of the child, as unwanted guests intrude into their privacy and sometimes they even make unjustified criticism or harsh comments. Therefore a shift is generally seen (as in the present case) in their attitude from neutrality or indifference to suppression of memories. In many cases, the parents take special measures to induce amnesia in their children for memories of previous lives. The measures are taken not only in India but other countries as well, like Sri Lanka and Turkey. The reasons for doing so are one or all of the following: a) there is a prevalent belief in most of the places that children who remember previous lives die young (although there is no confirmatory evidence from our data); b) fear of scorn or ridicule by others; c) fear of previous family's claim over the child; and d) fear of enmity (if the previous personality had been murdered) or harm to the child by the murderers.

When the two families concerned meet for the first time, both the families sometimes have apprehensions about each other's motives. The parents are afraid that the previous family might claim the child and the previous family is suspicious for fear of exploitation. Therefore members of the previous family do not blindly accept (or reject) the claims of the child. They satisfy themselves by examining the claims in their own way by interviewing the child, his family and some outsiders as well as carry out certain tests of recognition of the persons, possessions and places associated with the previous personality before accepting or rejecting the case. Rejection occurs mostly in cases where there is a large socioeconomic gap – the previous family members being socially or economically higher in status or where the knowledge or personal details described by the subjects (such as involvement in a murder or an illicit relationship) about the previous personality would bring shame or embarrassment to the previous family. However, in fairness it must be added that not all previous families with a large socioeconomic difference reject a case; in one case for example, a family of Thakurs had even adopted a low caste subject and in another case the family made considerable contributions to the marriage of the subject.

Once the previous personality's family is convinced about the genuineness of the case, the two families concerned continue to visit each other for varying lengths of time. In a majority of cases (72% of 118 cases interrogated), the two families concerned even exchanged gifts between them. Although the gifts were mostly given by the previous family, sometimes family of the subject gave gifts to the previous personality's family or both the families exchanged gifts. The value of the gifts ranged between a few rupees of cash or eatable to a sizable contribution by the previous family on special occasions such as subject's tying a rakhi on the wrist of previous personality's brother or even toward the marriage of a subject.

Attention received from outside the families sometimes strengthens (and sometimes even weakens) the case. Depending on the projection of a case, for instance, by the media sometimes leads to the embellishment of a case or induces fear in the families leading to a very guarded cooperation with the researchers as many of them cannot differentiate between the intentions and purposes of investigation of the two.

However, irrespective of the attitudes of the parents, of the previous families, or the outsiders, the features of the cases do not seem to get influenced. For example, the subjects start making statement about a previous life, on an average, between the ages of 2 and 4 years and continue to talk till 5 to 8 years (the usual age) across cultures. Their features do not appear to be much altered by the measures taken to suppress memories of the previous life, although in some cases children stop making reference to a previous life even if they do remember some of it. Nor are their features changed by the parental guidance or modeled after the available cases.[13]

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank University of Virginia for funding, NIMHANS, Bangalore for facilitating part of data collection and HIHT, Dehra Dun for academic support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stevenson I. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia; 1994. Twenty cases suggestive of reincarnation. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevenson I. American children who claim to remember a previous life. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171:742–8. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasricha S. Delhi: Harman Publishing House; 1990-2006. Claims of Reincarnation: An empirical study of cases in India. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasricha SK. Phobias in cases of the reincarnation type. NIMHANS J. 1996;14:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson I. Reincarnation and biology: A contribution to the etiology of birthmarks and birth defects. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1997;2 volumes [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haraldsson E, Samararatne G. Children who speak of memories of a previous life as a Buddhist monk: Three new cases. J Soc Psych Res. 1999;63:268–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson I. European cases of the reincarnation type. Jafferson, NC: McFarland and company; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haraldsson E, Majd Abu-Izzedin. Three randomly selected cases of Lebanese children who claim memories of a previous life. J Soc Psych Res. 2004;68:65–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keil HH, Tucker JB. Children who claim to remember previous lives: Cases with written records made before the previous personality was identified. J Sci Explor. 2005;19:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasricha SK, Keil HH, Tucker JB, Stevenson I. Some bodily malformations attributed to previous lives. J Sci Explor. 2005;19:359–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasricha SK. 2 Volumes. Delhi: Harman Publishing House; 2008. Can the mind survive beyond death? In pursuit of scientific evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasricha SK. Is familiarity with paranormal phenomena essential for mental health professionals? Delhi Psychiatr Bull. 2006;9:128–31. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasricha S. Are reincarnation type cases shaped by parental guidance? Empirical study concerning the limits of parent's influence on children. J Sci Explor. 1992;6:167–8. [Google Scholar]