Abstract

Background:

Suicidal behaviour among youth is a major public health concern in Sri Lanka. Prevention of youth suicides using effective, feasible and culturally acceptable methods is invaluable in this regard, however research in this area is grossly lacking.

Objective:

This study aimed at determining the effectiveness of problem solving counselling as a therapeutic intervention in prevention of youth suicidal behaviour in Sri Lanka.

Setting and design:

This control trial study was based on hospital admissions with suicidal attempts in a sub-urban hospital in Sri Lanka. The study was carried out at Base Hospital Homagama.

Materials and Methods:

A sample of 124 was recruited using convenience sampling method and divided into two groups, experimental and control. Control group was offered routine care and experimental group received four sessions of problem solving counselling over one month. Outcome of both groups was measured, six months after the initial screening, using the visual analogue scale.

Results:

Individualized outcome measures on problem solving counselling showed that problem solving ability among the subjects in the experimental group had improved after four counselling sessions and suicidal behaviour has been reduced. The results are statistically significant.

Conclusion:

This Study confirms that problem solving counselling is an effective therapeutic tool in management of youth suicidal behaviour in hospital setting in a developing country.

Keywords: Youth, suicidal behaviour, intervention, problem solving counseling

INTRODUCTION

Deliberate self-harm and suicide have been a major concern in many societies and on an average, daily suicides are around 3000 globally.[1] In the last five decades statistics on suicide has indicated a heavy upward trend.[2] The World Health Organization has predicted that by the year 2020 approximately 1.5 million people will commit suicide annually.[3] This amounts to an average of one death every 30 seconds and one attempt every one to two seconds.[4] Sri Lanka has recorded one of the highest rates of suicide in the world.[5]

The global suicide pattern among different age groups has distinctly changed in the recent past shifting toward youth from the elderly. At present, almost 60 percent of suicide deaths are among young adults in their productive years of life.[6] On par with the global situation, the Sri Lankan youth population has also become more vulnerable. The latest available data in Sri Lanka, in 2001, indicates that intentional self-harm was the leading cause of death among the youth belonging to the age group of 15 to 24 years.[7]

Attempted suicide is underreported in many countries including Sri Lanka.[8] The magnitude of attempted suicide is not clearly indicated, as no single reporting agency records the incidence of attempted suicide data.[6]

The literature on suicide suggested that suicide rates could be reduced if adequate preventive interventions were directed toward specific target groups, such as, individuals, families, schools or other sections of the society.[9,10]However, there was not much research carried out in the area of therapeutic interventions.

Counseling has been one therapeutic tool adopted in many countries to assist individuals with suicidal behavior due to stressful life events. The literature revealed that counseling has been a key element in many suicide prevention programs and in recent years, there have been attempts to apply a structured framework for counseling approaches. The problem-solving approach is one of the key counseling techniques largely used in the healthcare settings. The problem-solving approach is aimed at dealing with problems that emotionally disturb the client and require practical solutions.[11,12]In this scenario, the problem-solving approach is generally very helpful as the client would be able to deal with the stressful life events and also prevent future life events becoming overwhelming.

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of problem-solving counseling as a therapeutic tool on youth suicidal behavior in a suburban hospital in Sri Lanka.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study consisted of two parts; one was descriptive, aimed at identifying the risk factors associated with suicidal behavior and the other a comparative study on the focused area of this article. The study was based on a suburban hospital in Sri Lanka, and the Base Hospital at Homagama, in Colombo District, was selected. Hospitals that already had existing psychiatric units/wards were excluded, as deliberate self-harm (DSH) patients admitted to these hospitals were subjected to specific assessments and treatment including counseling, making it difficult to design this study as a case control study. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura. A pilot study was carried out with ten patients with DSH, admitted to the same hospital, in order to determine the acceptability of the questionnaires.

Patients who were engaged in DSH, as recorded by the medical officers in the medical records, between the age group of 15 and 24 years, who had given consent in writing to participate in the study after verbal and written explanation, and were not diagnosed as having a major psychiatric disorder, and who were categorized as medium- and low-intent cases on the suicide intent scale,[13] were recruited for the study. These patients were assessed by the main researcher within 48 hours of admission. The study period was 15 months.

The tools used were a Semi Structured Questionnaire to obtain the sociodemographic characteristics; the Mental State Examination to identify the psychiatric disorders; the Suicide Intent Scale to measure suicide intent; and the Individual Visual Analog Scale to measure the ability to solve problems on different dimensions. In the initial assessment, the suicide intent of the patient was measured by a clinical interview, using the Suicide Intent Scale developed by Pierce.[13] The purpose of applying the Suicide Intent Scale was to quantitatively determine the suicide intent of the subjects and to refer those with high-intent for further psychiatric intervention. The scale dealt with the circumstances related to the suicide attempts, self-reporting items, and items dealing with the medical risk of self-injury. Subjects who were graded as medium- and low-intent were recruited to the study and those who graded as high-intent were referred for psychiatric assessment to the Teaching Hospital of Colombo South, situated 10 km away from the Base Hospital of Homagama.

Individual Visual Analog Scale (IVAS) was used as an independent tool to assess the effectiveness of problem-solving counseling. IVAS was constructed using the Likert scale,[14] with ten statements giving five response categories, to measure the effectiveness of counseling. These statements were designed to assess the subject's capability of understanding more about one's own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, ability to build up a relationship with others, ability to identify real problems, ability to find alternative solutions, capability of understanding the importance of setting goals, seeking help and support when necessary, ability to change, helping own self, ability to cope with life's circumstances, and confidence when approaching future problems. This scale has been in use as an evaluation tool for assessment of effectiveness of counseling offered to DSH patients at the university Psychiatry Unit of the Colombo South Teaching Hospital. In order to make a comparison, the IVAS was administered to both the experimental and control groups at the initial assessment, as a baseline assessment and subsequently six months after, to measure the difference between the groups, if any. During the 15-month period, a total of 371 patients were admitted to the hospital with suicidal behavior. Of them, 124 subjects who satisfied the inclusion criteria were recruited to the study, considering the dropout rate of 32.8 percent.[15] All eligible patients were allocated to the experimental and control groups one by one during the study period, until the desired numbers were reached.

Those patients recruited to the study were informed of the purpose of the study, their involvement, interaction procedure, and expected level of participation. Written consent was obtained prior to the initial assessment. Confidentiality of the information disclosed by the patient was assured. In patients who were below 18 years their parents/guardians were also contacted to obtain their consent. The working model adopted was problem-solving. Literature on problem-solving counseling revealed that experts had promoted different approaches describing four to seven steps.[16,17]In this study the six-step approach suggested by Andrews and Hunt[18] was adopted. The six steps were: identification of the problem, listing out all possible solutions, assessing each possible solution, selecting the suitable or most practical solution, planning how to carry out the best solution, and reviewing the progress.

Each subject allocated to the experimental group was offered four one-hour sessions of problem-solving counseling by the same therapist. The six steps of the problem-solving techniques discussed earlier were applied and each counseling session was pre-determined. The first session was offered to each subject after the initial assessment. Subsequent sessions were offered one week, two weeks, and one month after the first session. The second, third, and fourth sessions were offered at the residences of the subjects and those who did not wish to continue sessions at their residences were given the opportunity at the Base Hospital, Homagama.

Patients who did not improve after four sessions were guided to the Psychiatric Unit of the Teaching Hospital of Colombo South, for further assessment. The control group received routine services: referral to a medical officer, psychiatric referral, and referrals to other agencies. Therefore, the control group too did not remain as an untreated group.

RESULTS

During the study period of 15 months, 371 patients with suicidal attempts were admitted to the Base Hospital, Homagama, with a sex ratio of 100 females to 89.3 males. Of all the admissions with suicidal attempts, 165 patients (44.5 percent of admissions) with suicidal behavior were within the age group of 15 and 24 years, and gender ratio was 100 females to 54.2 males. During the 15-month study period 124 subjects were recruited allocating them one after the other into the experimental and control groups.

The demographic data of the sample revealed a female preponderance with a sex ratio of 49.4. Age distribution in the study sample showed a considerable increase in suicide attempts at the age of 17 with 17.7 percent, and at the age of 24 with 15.3 percent. A number of explanations for these increased rates of attempted suicide in these specific ages could be proposed. One rationalization is with regard to the attainment of the major school education milestone being around age 17 and failure of such achievements. The explanation for witnessing a considerable increase of attempted suicides at the age of 24 may be due to the fact that youth at this age tend to participate more visibly in the public domain. When the youth experience factors such as unemployment, which generally are associated with low self-esteem, economic, social, and psychological insecurity, they may lead to suicidal behavior. However, further study is required to confirm such an explanation.

Marital status

The demographic data of the sample revealed that that 71.8 percent of the total sample were single and 25 percent were married. The balance subjects were divorced, separated, and living together.

Educational attainment

One subject had not attended school at all and two had only primary education. Twenty-two subjects (17.7 percent) had studied only up to grade eight. Fifty-seven subjects (46.0 percent) had studied only up to General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level) Examination. Altogether 66.1 percent of the sample had been unsuccessful in achieving the minimum national level educational qualification, that is, passing the G.C.E. (OL) Examination, either to continue higher education or to gain reasonable employment.

Occupation

The total subjects of 41.9 percent, who were more than 18 years of age, were unemployed and also not engaged in any full time educational or skill training endeavor. This study revealed that 14 subjects were students and 54 (43.5 percent) were employed. Based on the International Standard Classification of Occupation (International Labor Organization, 1988), more than half of the employed subjects fell into the categories of craft workers and elementary occupations.

Suicidal intent

In the initial assessment, suicidal intent was measured by the clinical interview, and quantitatively measured using the Suicide Intent Scale developed by Pierce (1981). Accordingly seven patients who scored more than 11 in the suicide intent scale were excluded and were referred to the psychiatry unit of the Colombo South Teaching Hospital.

Out of the 165 youth admitted to the hospital with DSH, during the study period, a total of 41 patients were excluded due to death, diagnosed as having psychiatric disorders, and being critically ill. All components of the initial assessment were completed by 62 subjects in each group. Forty-six from the control and 55 from experimental groups responded to the final assessment. The overall response rate was 81.5 percent. Of the 124 in the study sample, the number of dropouts was 23, and the dropout rate was 18.5 percent. The results of the initial assessment and final assessment are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

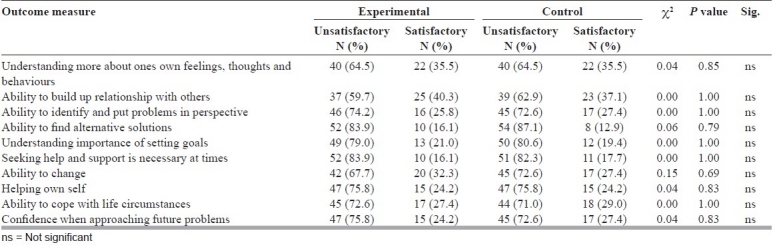

Table 1.

Comparison of the problem solving ability of the subjects in both groups - Initial assessment using Individual Visual Analogue Scale

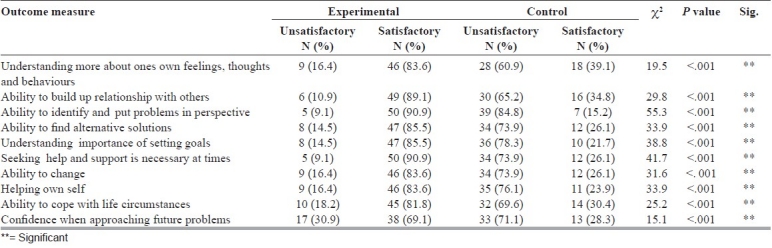

Table 2.

Comparison of the problem solving ability of the subjects in both groups: Final assessment using Individual Visual Analogue Scale

The problem-solving ability, as assessed by a 10-item questionnaire, did not show any statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups, during the initial assessment. In the final assessment it was revealed that all items showed statistically significant improvement in the experimental group.

Specific outcome measures: 83.6 percent of the experimental group had a satisfactory level of improvement in developing the skill of understanding more about ones own feelings, thoughts, and behavior toward the specific problem. The control group recorded only 39.1 percent increment; 90.9 and 15.2 percent of the experimental group and control groups, respectively, showed a satisfactory level of improvement in their ability to identify and put problems in perspective.

In the experimental group, there was an increase from 45.5 to 89.1 percent in their ability to build up relationships with others; 85.5 percent in the experimental group had developed skills to search for alternatives and understood the concept of setting goals against 21.7 percent in the control group. In the experimental group, 90.9 percent had understood the importance of seeking help and support when necessary, compared to 26.1 percent in the control group. However, in the analysis of the dataset it was also found on certain occasions, based on the nature of the problem and social stigma, some were reluctant to seek help, especially in instances such as assault by spouse, extra-marital relationship of parents, sexual abuse, and the like. In the experimental group, 83.6 percent had shown improvement over the control group (26.1 percent) in their ability to change the outcome measure. After the therapeutic intervention, it was found that there were no repeated suicidal attempts in the experimental group while there were two attempts in the control group.

DISCUSSION

This study sample represented youth who attempted to harm themselves and who were admitted to the Hospitals in Sri Lanka. Of the 124 study sample, the number of dropouts was 23 and the dropout rate was 18.5 percent. This was less than the expected dropout rate of 32.8 percent, as described in previous mental health studies carried out in Sri Lanka[15] Gender distribution showed a female preponderance in this study and this was consistent with the other studies on suicidal behavior, indicating that attempted suicide rates among females were much higher than males in many countries.[19] The age distribution of the sample showed increased rates of attempted suicide in ages of 17 and 24. Explanation of such a distribution in the sample was not possible with the available data.

The preponderance of unmarried subjects in the sample was not an overrepresentation. More than 50 percent of the females in the age cohort of 15 to 24 were nevermarried.[20,21]This study revealed that 14 subjects (11.3 percent) were students and 54 (43.5 percent) were employed, more than half of the employed subjects fell into the categories of craft workers and elementary occupations and two were technicians. No subjects were in the occupation categories of senior officials, managers or professionals. The study revealed that ‘poor educational attainment’ had been a major characteristic among the sample, and most of the subjects had not achieved considerable educational attainment. Altogether 66.1 percent of the sample was unsuccessful in achieving minimum national level educational qualification, that is, passing the G.C.E. (OL) Examination, either to continue in higher education or to gain reasonable employment. The trend of poor educational attainment among attempted suicide victims was consistent with the findings of a study carried out by de Silva and de Alwis Seneviratne,[22] indicating that 85 percent of the attempted suicides were poorly educated, having less than 11 years of schooling.

Counseling as a therapeutic intervention

According to the findings of our study, problem-solving counseling is an effective therapeutic intervention that improved coping skills, problem-solving abilities, and also reduced suicidal behavior among the youth in a suburban community in Sri Lanka. This is consistent with the opinion made by the World Health Organization, indicating that problem-solving therapy is one of the key intervention methods, which could reduce suicidal behavior.[5] Therefore, four sessions of problem-solving counseling can be used as a therapeutic tool in medical institutions and in the community, to reduce suicidal behavior. Repeated interventions offering problem-solving counseling will facilitate and strengthen help-seeking behavior. Analysis of specific outcome measures also show important aspects of the study group that represent the youth who attempt DSH in the country and aspects on therapeutic interventions.

The level of effectiveness of the problem-solving ability varied depending on the individual's capability of achieving the expected outcome of specific stages in the problem-solving counseling process. The Individual Visual Analog Scale (IVAS) used in the assessment during the study, facilitated the understanding of most of the individualized outcome measures on different levels of problem-solving counseling applied in this study. Understanding more about ones own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, the ability to identify and put problems in perspective, the ability to build up relationships with others, the ability to find alternative solutions, understanding the importance of setting goals, the ability to change, helping own self, and seeking help and support when necessary, had improved remarkably among a majority of the subjects in the experimental group. As Lewis and Lewis[23] argued, exploring the experiences, behaviors, and feelings that related to the problem, provided an entry point in defining the problem.

Subjects in the experimental group had shown a more enhanced ability than the control group, to understand the context of specific problems and how such problems affect the subject and their immediate associates, including family members. In the counseling sessions, the subjects were encouraged to understand the importance of maintaining relationships, the awareness of how subjects and others react and interact, and dealing effectively with disagreements, problems, conflicts, and so on, as building up relationships with other persons created network ties and worked against isolation. Individuals who developed meaningful relationships, shifted from isolation and tended to reduce suicidal thoughts.[24] The experimental group had gained the ability to build up relationships with others during the six-month period. Goldsmith et al.[25] was of the opinion that those who enjoyed close relationships with others, coped better with various stressful life events, and also had better psychological and physical health. The results of the study demonstrated that through counseling sessions, a significant number of subjects (85.5 percent) in the experimental group had developed skills to search for alternatives. The ability to identify and formulate suitable solutions to a particular social issue was a vital aspect in addressing suicidal behavior.[17,23,26]Furthermore, it was noted that 85.5 percent of the subjects in the experimental group had understood the concept of setting goals against 21.7 percent of the subjects in the control group Goal setting was a key element in the problem-solving counseling process where the individual viewed the problem with a new perspective and understood the need for action.

Through counseling sessions, the subjects are encouraged to seek help and support and the results of the evaluation show that the experimental group has a higher level of willingness to seek help and support when necessary, than the control group. Carmel et al.[27] have found that seeking social support is one of the tested problem-solving dimensions and it is lower among repeaters than non-repeaters. Having a helping hand at the time of crisis eases the individual's ability to cope with a stressful situation and it is argued that social support is a protective factor against suicidal behavior.[25] The ability to change is another important outcome measure, which showed significant improvement in the experimental group. When the subjects discover their ability to make the desired changes in their lives, they become more confident in positively responding to problem situations and stressful life events. In this scenario, it is evident that ensuring continuous access to problem-solving counseling for disturbed youth will have an impact on reducing the suicidal thoughts among them. Studies have confirmed that the problem-solving approach seems to reduce suicidal ideation and is more effective than treatment as usual or nondirective therapy.[25] After therapeutic intervention, there have been two repeated suicidal attempts in the control group, while there have been none in the experimental group. This confirms the work of Eskin, Ertekin, Demir[28] who have demonstrated that the problem-solving therapy has significantly contributed to a decrease in suicide risk among youth. Similarly Salkovskis, Paul, Storer[29] have found that brief problem-solving treatment may be effective in reducing the risk of repeated suicides.

In the final assessment, it was also tested how the groups felt about their suicidal act and it was reported that 100 percent of the experimental group felt that their suicide attempt was unwise, while only 26.1 percent in the control group felt so. In this scenario, it could be inferred that orientation received through four counseling sessions had helped the subjects to search for alternatives to fit into the society rather than expel them from the society.

CONCLUSION

According to the findings of this study, problem-solving counseling is found to be an effective and culturally acceptable therapeutic tool in secondary prevention of suicides, among the suburban youth in Sri Lanka. It improves coping skills in the target group, which enables them to cope with life stressors. The study also shows that four counseling sessions offered during a one-month period is effective in reducing suicidal behavior and improving the coping ability on several dimensions. However, a minority of youth need longer or more specific therapeutic interventions to bring about lasting changes in their lives. It is recommended that four sessions of problem-solving counseling be offered to the target group, after screening for serious psychiatric disorder and high suicidal intent, in the medical institutions they present to.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. Dayalal Abeysekera of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Staff of the Homagama Base Hospital, and all patients who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO World Suicide Prevention Day, 10 September 2007: Suicide prevention across the life span. [cited on 2008 April 30]. WHO statement 2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s16/en/index.html .

- 2.WHO Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Facts and Figures Suicide Prevention: Emerging from Darkness. 2006. [cited on 2008 May 12]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section1174/Section1199/Section1567/Section1824_8078.htm .

- 3.WHO. Choosing to die - a growing epidemic among the young. [cited on 2008 May 05];Bull World Health Organ. 2001 79:1175, 7. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/bulletin/2001/issue12/79(12)1175-1177.pdf . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidalogi. 2002;7:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. For Which Strategies of Suicide Prevention is There Evidence of Effectiveness, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Denmark. 2004. [cited on 2008 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/document/E83583.pdf .

- 6.Suicide Prevention: Emerging from Darkness, World Health Organization-Regional Office for South East Asia. 2001. p. 12. WHO.

- 7.Department of Health Services, Annual Health Bulletin, Department of Health Services, Sri Lanka. 2006. [cited on 2009 Oct 10]. Available from: http://203.94.76.60/AHB2006/AHS-2006(PDF%20FILES)%20for%20WEB/9%20detailed%20tables mortality%20and%20morbidity.pdf .

- 8.Weerackody C. Some Features of Attempted Suicide in Sri Lanka. In: de Silva P, editor. Suicide in Sri Lanka. 1989. p. 41. Sri Lanka: Institute of Fundamental Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsay RF. Suicide Prevention Strategies within A United Nations Context. In: Ramsay RF, Tanney BL, editors. Global Trend in Suicide Prevention: Towards the Development of National Strategies for Suicide Prevention. Mumbai, India: Tata Institute of Social Sciences; 1996. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The World Health Report. 2001. p. 73. Geneva Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope.

- 11.Palmer S, Dryden W. New Delhi: Sage Publications; 1995. Counseling for Stress Problems; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer S. Problem focused stress counseling and stress management training. 1997. [cited on 2005 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.managingstress.com .

- 13.Peirce DW. The predictive validation of a suicide intent scale: A five-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;139:391–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babbie ER. 4th ed. California: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 1986. The Practice of Social Research; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perera H, Perera R. User satisfaction with child psychiatry outpatient care: Implications for practice. Ceylon Med J. 1998;43:185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kathriarachchi ST, Manawadu VP. Deliberate Self-harm (DSH): Assessment of patients admitted to hospitals. 2002:17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeo A. Singapore: Armour Publishing Pvt Ltd; 1993. Counseling a problem-solving approach; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews G, Hunt C. Treatments that work in anxiety disorders. [cited on 2008 Apr 18];Med J Aust. 1998 168:628–34. Available from: http://www.mja.com.au/public/mentalhealth/articles/andrews/Andrews.html . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidtke A, Bille BU, de Leo D, Kerkhof A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: Rates, trends and socio demographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989-1992. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:327–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka Demographic and Health Survey, Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2002. p. 120.

- 21.Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka Demographic and Health Survey, Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2003. p. 81.

- 22.De Silva D, de Alwis Seneviratne R. Deliberate Self-harm (DSH) at the National Hospital Sri Lanka (NHSL): Significance of Psychology Factors and Psychiatric Mobility. J Ceylon Coll Physicians. 2003;36:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JA, Lewis MD. California: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; 1986. Counseling programmes for employees in the workplace; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry AF, Short JF. London: Collier-Macmillan Limited; 1954. Suicide and homicide; pp. 16–7. The free press of Glencoe. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Washington: DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [cited on 2008 Mar 16]. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10398.html . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehy N, O'Connor R. Cognitive Style and Suicidal Behavior: Implications for Therapeutic Intervention, Research Lacunae and Priorities. Br J Guid Counc. 2002. [cited on 2008 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.psychology.stir.ac.uk/staff/roconnor/documents.BJGC2000.pdf .

- 27.Carmel M, Helen SK, Paul C. Problem-solving and repetition of para suicide. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2002;30:385–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eskin M, Ertekin K, Demir H. Efficacy of a Problem-Solving Therapy for Depression and Suicide Potential in Adolescents and Young Adults. [cited 2008 Mar 29];Cognitive Therapy and Research [Internet] 2007 32:227–45. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/x5322100p0575339/fulltext.pdf?page=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salkovskis M, Paul AC, Storer D. Cognitive Behavioural Problem Solving in the Treatment of Patients who Repeatedly Attempt Suicide A Controlled Trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:871–76. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]