Abstract

A two-dimensional or transverse acoustic trapping and its capability to noninvasively manipulate micrometersized particles with focused sound beams were experimentally demonstrated in our previous work. To apply this technique, as in optical tweezers, for studying mechanical properties of and interactions among biological particles such as cells, the trapping forces must be calibrated against known forces, i.e., viscous drag forces exerted by fluid flows. The trapping forces and the trap stiffness were measured under various conditions and the results were reported in this paper. In the current experimental arrangement, because the trapped particles were positioned against an acoustically transparent mylar membrane, the ultrasound beam intensity distribution near the membrane must be carefully considered. The total intensity field (the sum of incident and scattering intensity fields) around the droplet was thus computed by finite element analysis (FEA) with the membrane included, and it was then used in the ray acoustics model to calculate the trapping forces. The membrane effect on trapping forces was discussed by comparing effective beam widths with and without the membrane. The FEA results found that the broader beam width, caused by the scattered beams from the neighboring membrane and the droplet, resulted in the lower intensity, or smaller force, on the droplet. The experimental results showed that the measured forces were as high as 64 nN. The trap stiffness, approximated as a linear spring, was estimated by linear regressions and found to be 1.3 to 4.4 nN/µm, which was on a larger scale than that of optical trapping estimated for red blood cells, a few tenths of piconewtons/nanometer. The experimental and theoretical results were in good agreement.

I. INTRODUCTION

Optical trappings [1] have frequently been employed to measure forces and displacements associated with biomechanical activities of various cells and molecules [2], [3]. Three calibration methods [4]–[6] have often been used to measure the trapping forces on such particles. First, the equipartition theorem describes a bead’s motion bound in a potential well, and the statistical variance of the bead location is converted to the corresponding force. The force calibration is carried out by measuring thermal fluctuations of trapped beads and can be readily done without the knowledge of particle size or shape, but the method depends upon position detection systems involved [4]. Second, given that a trapped bead’s motion can be treated as a Brownian random walking, the spectral analysis approximates the spatial spectra of the motion as a Lorentzian. Its corner frequency, at which the peak magnitude is reduced to its 3-dB value, is linearly linked to the resultant force [5]. Third, the viscous drag force caused by a flowing fluid is used to counter balance the lateral trapping forces on a particle [6].

Recently, transverse acoustic trapping was experimentally implemented [7], [8], and it is crucial to learn the absolute magnitude of the forces generated in these traps to allow them to be used in biomedical experiments. To calibrate these forces, the drag force approach, among the aforementioned methods, was best suited to our current experimental setting. This paper, as a subsequent work of the recent implementation, reports an approach developed to measure the transverse trapping forces, and under certain conditions, the trap stiffness. The experimental results were then compared with theoretically predicted values.

II. METHODS

A. Framework of Acoustic Trapping

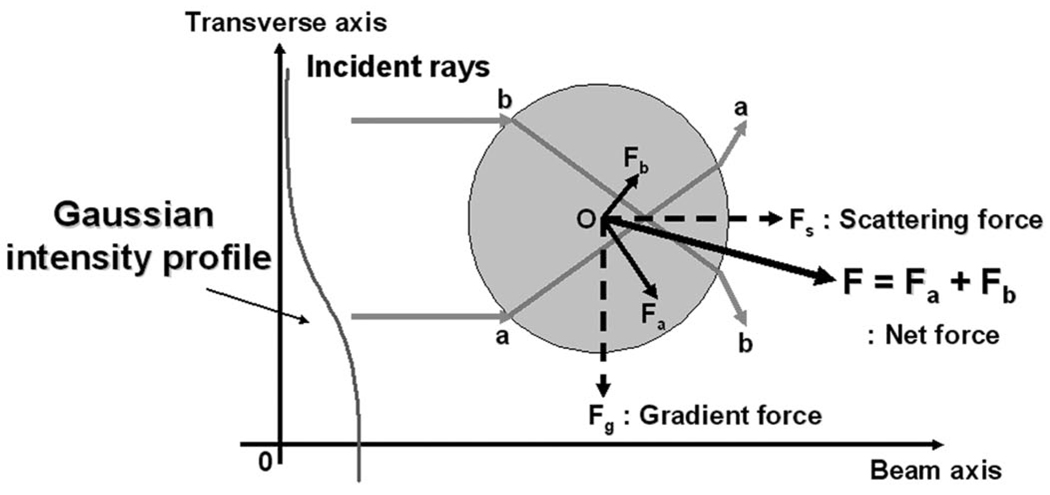

The underlying principle of acoustic traps is illustrated in Fig. 1: two incident rays are shown to be incident upon a sphere in an ultrasound beam with a Gaussian intensity distribution. As the rays interact with the sphere, multiple scatterings result in momentum transfer from the rays to the sphere. The two exciting rays generate forces on the sphere denoted Fa and Fb. Note that Fa is stronger than Fb (Fa > Fb) in higher-intensity area. The intensity difference between the exciting rays, as a result, induces a net force F (or acoustic radiation force), and subsequently directs the sphere toward the beam axis. The forces are known to consist of two components, scattering and gradient forces. The scattering force Fs, arising from reflection, pushes a particle away in the direction of the beam propagation, whereas the gradient force Fg, originated from refraction, attracts it toward the beam axis, and serves as a restoring force that could be used as a particle trapping [9]. In particular, Ashkin [10] found that optical traps for dielectric spheres could be formed by a single focused laser beam, when the gradient forces prevail over the scattering forces.

Fig. 1.

Principle of acoustic trapping: a sphere is interrogated by two representative rays (a and b) in Gaussian intensity profile. The net force, associated with its scattering and gradient components, acts on the sphere, as momentum transfer from the rays to the sphere occurs. As a result, the sphere moves toward the beam axis.

A 30-MHz lithium niobate (LiNbO3) transducer with an f-number of 0.75 was fabricated to achieve steep intensity gradients around particles needed to create acoustic traps. Lipid droplets (BioMiNT lab, UC Irvine) were synthesized as target particles for trapping, because their acoustic impedance (1.3 MRayls) is similar to that of surrounding medium, i.e., water (1.5 MRayls) [11], and therefore reflections can be considerably reduced. Note that the resonant motion of droplets, in contrast to solid particles [12], was considered negligible because of their fluidic property. The mean droplet size was 105 µm in diameter, larger than the wavelength (42 to 50 µm) to meet the ray acoustics conditions.

B. Experimental Procedure

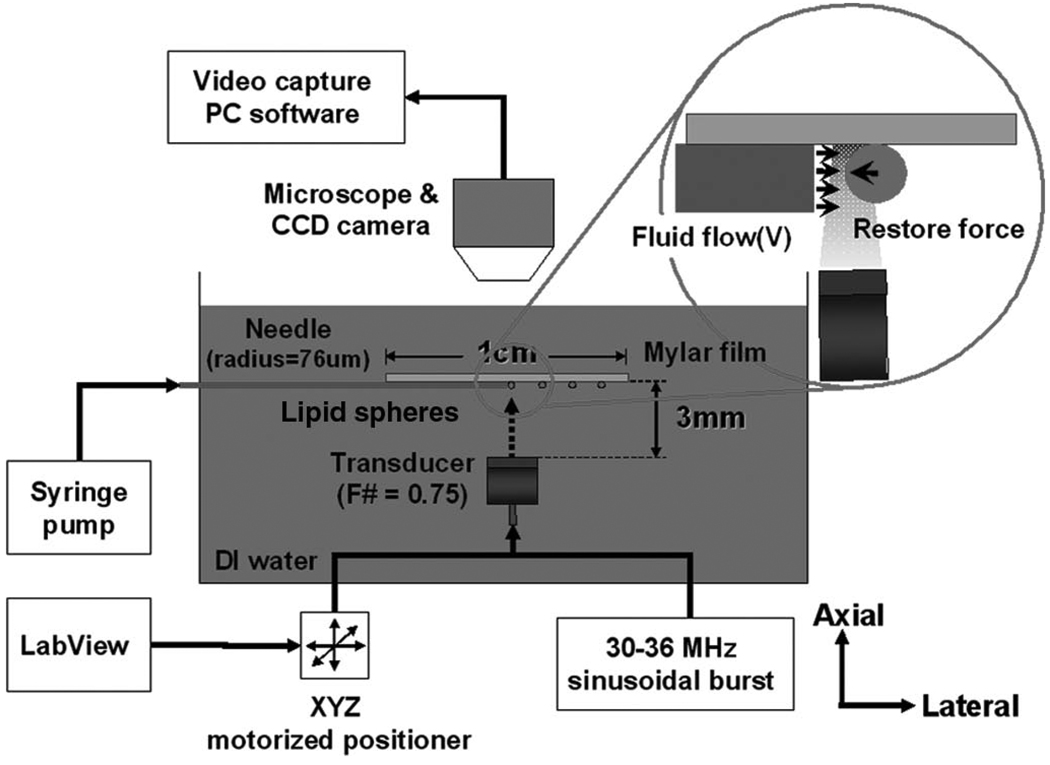

Fig. 2 illustrated the experimental system that consisted of two parts, one for trapping and the other for drag force application. The single element transducer was first focused at 3 mm, i.e., the surface of a thin mylar membrane, and was subsequently shifted downwardly in the axial direction by the radius of a droplet. As a result, the transducer’s geometrical focus and the center of the droplet were at the same point. The transducer was then mechanically translated to trap a droplet, and excited in sinusoidal bursts at 30, 33, and 36 MHz, with variable voltages from 70 to 130 mVpp followed by 50 dB amplification. Positive peak pressures for each condition were measured by a calibrated needle-type hydrophone (HPM04/01, Precision Acoustics, Dorchester, UK) having an active element 40 µm in diameter. The trapped droplet was positioned at the exit of a micropipette having an inner diameter of 152 µm and a wall thickness of 30 µm. Note that trapped droplets, suspended in the deionized water, were in contact with the membrane, and its buoyant motion was thus restricted. The surface friction of the membrane was neglected for the sake of simplicity. Fluid drag forces were then simultaneously exerted on the trapped droplet, and produced from a flow cell, where the micropipette was connected to a syringe pump (Pump 11 Pico Plus, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). At steady state, a sufficient lead in the pipette’s length allowed the flow to become fully developed, and the flow rate was varied from 0 to 100 µL /min. Typically, the distance between the pipette tip and the droplet was kept at less than 500 µm, and therefore the flow velocity was specified at the pipette exit. The rate was initially set at the minimum level, and slowly increased until the droplet escaped from the trap.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of trapping force calibration: the inset illustrates the flow cell, where drag forces were applied to a suspended droplet. Fluid flows were simultaneously provided from the pipette while the droplet was trapped.

The droplet motion was then captured through a microscope (SMZ1500, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and a commercial software, Infinity Analyze (Lumenera, Ottawa, ON, Canada), determined the droplet displacements with respect to the trap center. Both displacements and flow rates were measured until drag forces exceeded trapping forces, i.e., trapping force reached its maximum.

C. Simulation of Trapping Force

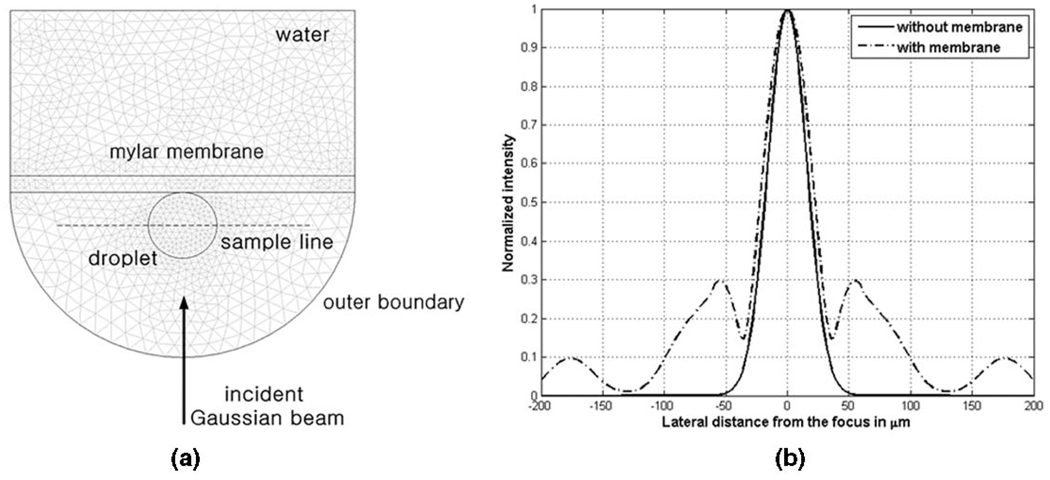

Because the mylar membrane interacted with both droplets and incident waves in the current experimental arrangement, its effect must be taken into consideration. Hence, FEA was carried out using COMSOL Multiphysics (COMSOL Inc., Burlington, MA) to simulate the acoustic fields near the membrane. The total intensity field was obtained by summing incident and scattered intensities around the droplet. The resultant intensity distribution was then used in the ray acoustics model. Fig. 3(a) illustrates the model geometry and its structured meshes; the number of meshes was 1113, and the degree of freedom was 42880. It was assumed that the densities of water and droplet were 1000 and 950 kg/m3, respectively, and the sound speeds were set to 1500 and 1450 m/s, respectively. The beam focus was placed at the center of the droplet, and the membrane thickness was 20 µm. The Sommerfeld radiation condition was applied to prevent outgoing scattered waves from being reflected at the outer boundary back to trapped droplets. The intensity distribution at 30 MHz and 2.2 MPa was obtained along the sample line, as seen in Fig. 3(b), and showed that the 3-dB beam width calculated by the FEA was 42 µm, whereas it was 38 µm in the ray acoustics model (without the membrane), equal to the beam width of an ideal Gaussian intensity. The resultant intensity profile I(x, y), obtained from the FEA model including the droplet, deviated from the ideal Gaussian shape because the scattered waves from the membrane and the droplet interfered with the incident beams, particularly outside the beam width. The trapping forces F were then calculated with the intensity I(x, y) as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

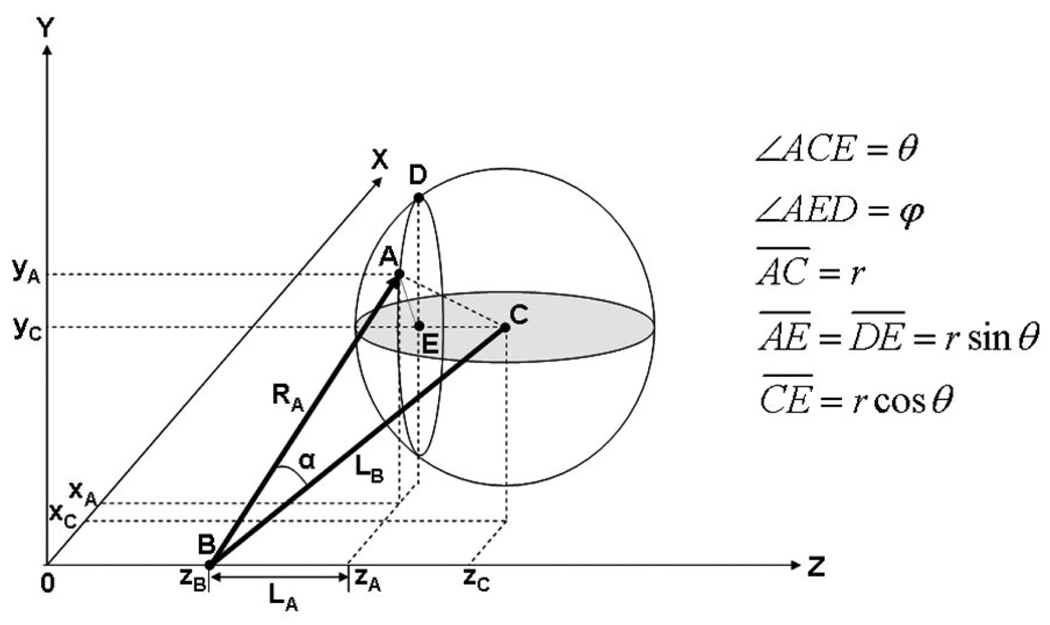

where RA, LB, and α were specified in Fig. 4; w and w0 are the beam widths at z and the focal point, and P is the incident acoustic power emitted by the transducer; r and cw are the droplet radius and the speed of sound in water, respectively; θi and θr are the incident and refracted angles; R and T are the reflection and transmission coefficients between two media; Zw and Zp are the acoustic impedances of water and the droplet. Qs and Qg represent the trapping efficiencies with respect to scattering and gradient components. Because of the focused beam shape, incident angles on a sphere determined the directions of both scattering and gradient components, depending on where the beam arrived on the sphere. An axial point zB, regarded as an imaginary beam source, was thus needed to consider such condition. It was defined as a z-intercept where a line with the tangential slope at an incident angle intersected with the z-axis or the beam axis.

Fig. 3.

Simulation of membrane effect on intensity distribution along the plane containing the center of the droplet: (a) 1113 triangular meshes (or elements) were generated by COMSOL Multiphysics, to solve the Helmholtz equation. (b) Normalized intensities, calculated along the dotted line in (a), were compared between the two cases. The FEA results (with membrane) yielded a wider beam width of 42 µm than 38 µm in the ray acoustics model (without membrane).

Fig. 4.

Model geometry of ray acoustics and parameter definition (adopted from Lee et al. [13]).

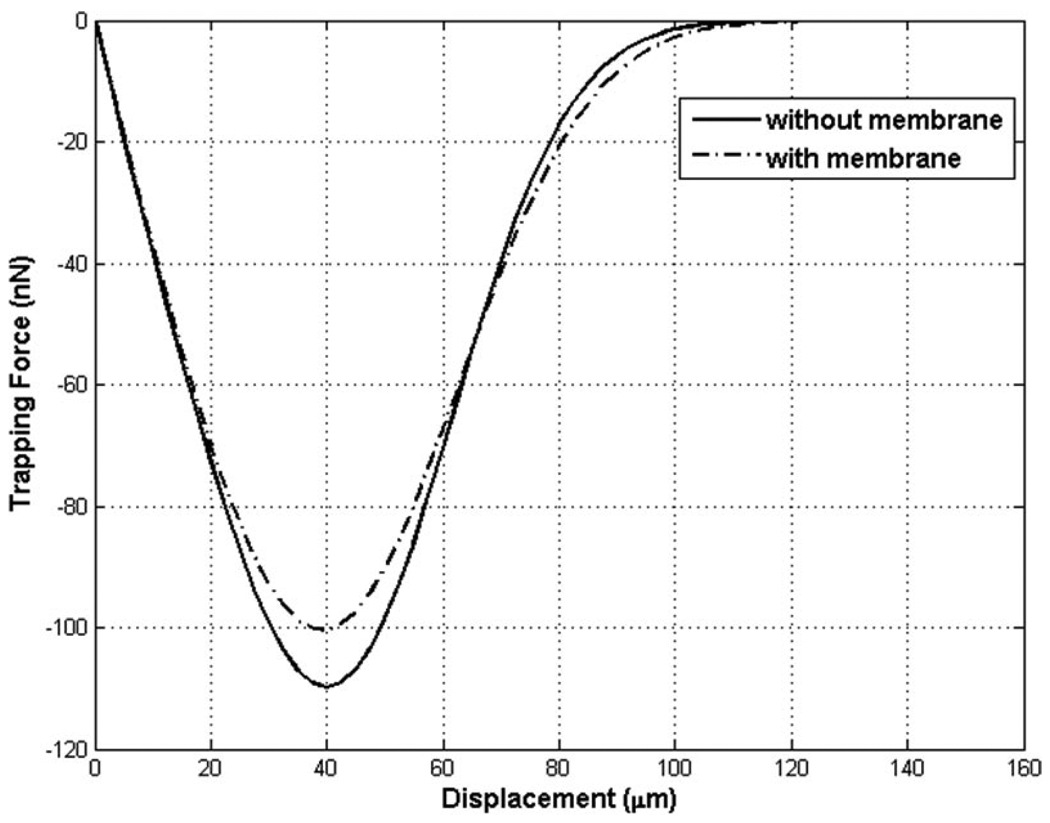

Fig. 5 indicated that the forces were reduced by the presence of the membrane, compared with those without the membrane. This was because the broader beam width, caused by the scattered beams from the neighboring membrane and the droplet, resulted in a lower intensity, and therefore induced smaller force at the vicinity of the focus. Far beyond the beam width, in contrast, the force produced from a non-Gaussian intensity profile was stronger than from its ideal Gaussian distribution. This could be predicted as well, because such residual beams, instead of being scattered away, were considerably built up; the beam’s intensity at 54 µm was reduced by 5 dB from its normalized peak, as illustrated in Fig. 3(b). Droplet displacements at maximum trapping forces are compared between the experiment and the simulation results in the subsequent section.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of trapping forces with and without membrane at 30 MHz. The trapping forces without the membrane (solid line), because of its narrower beam width, were stronger than those when the membrane was present (dotted line), whereas that relation was reversed outside the beam width.

III. RESULTS

A. Measurement of Trapping Force

At a given flow rate, the trapping forces (Ft) acting on a displaced droplet within the trap faced equal and opposite drag forces (Fd) caused by the flow when both components were balanced. According to Stokes’ law [14], therefore, the trapping forces on the droplet are given by:

| (4) |

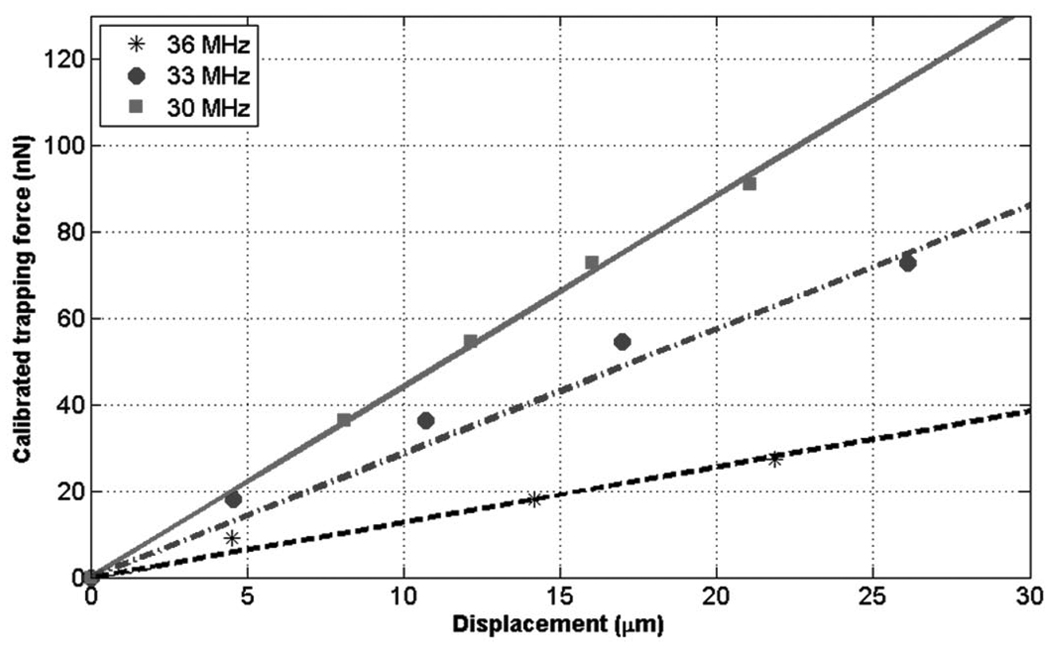

where η and r are the dynamic viscosity of water and the droplet radius, respectively. v is the flow velocity; in the current arrangement, it could be increased to as high as 92 mm/s. To determine the drag coefficient, β, where the trapped droplet was in contact with the membrane, the results from a sphere model [15] were employed because the model considered the same situation as the current problem. It was assumed that a sphere in a laminar flow was in contact with a fixed plane, and that inertial terms in the Navier-Stokes equation were neglected for low Reynolds numbers, less than 4.6 in this study. No boundary layer exists under this condition. As a result, β was set to 1.7009. Fig. 6 shows the calibrated trapping forces as a function of displacement at 30, 33, and 36 MHz. Peak pressures generated by the transducer were 2.2, 2.0, and 1.3 MPa at the focus, respectively. As the flow rate was increased to 100 µL /min (or equivalently 92 mm/s flow velocity), the droplet was released from the trap when displaced from the trap center by 26 µm at 33 MHz. The trapping force, at each frequency, was measured in the tens of nanonewton range, and its magnitude increased as the droplet was further displaced.

Fig. 6.

Measured trapping forces as a function of displacement at different frequencies. Linear regression curves on the measured data were obtained to calculate the trap stiffness. The values at 30, 33, and 36 MHz were 4.4, 2.9, and 1.3 nN/µm, respectively. The stiffness was thus increased until the frequency reached the center frequency of the transducer.

At the resonant frequency of 30 MHz, for example, the measured force was as high as 93 nN, whereas it was reduced to 28 nN at 36 MHz. Given the same peak pressures throughout the frequency range, it is expected that smaller forces would be generated at lower frequencies because of wider beam widths or, in turn, lower intensities at the focus.

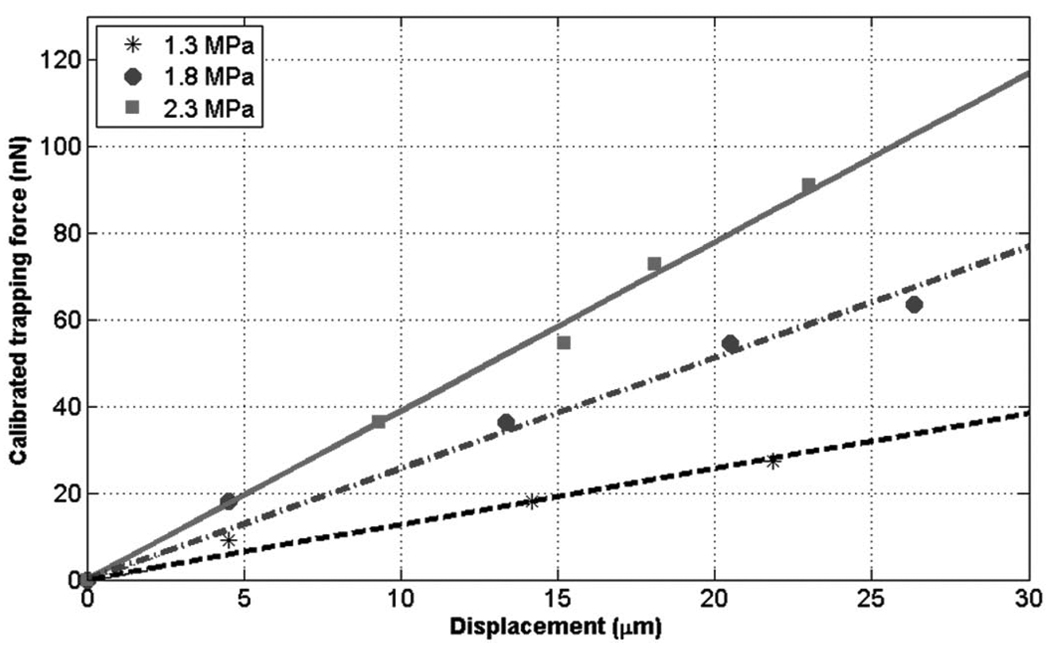

The trapping forces, driven by different peak pressures, were also calibrated at 36 MHz as shown in Fig. 7. It was shown that the force was 91 nN for 2.3 MPa, and 64 nN for 1.8 MPa. Hence the results demonstrated that higher acoustic pressures induced stronger trappings within the transducer’s bandwidth, i.e., 50%.

Fig. 7.

Measured trapping forces at different pressures. The forces at 36 MHz increased as the pressures became higher. The trap stiffness was found to be 1.3, 2.6, and 3.9 nN/µm, as the pressures were given at 1.3, 1.8, and 2.3 MPa. This indicated that the higher pressure produced the stiffer trap.

B. Determination of Trap Stiffness

A droplet in an acoustic trap can be approximated, as in optical traps, as if attached to an elastic spring at the focus. Linear regressions were thus performed to compute the trap stiffness, the ratio of force to displacement, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The stiffness was represented as a function of applied peak pressure, and varied from 1.3 to 4.4 nN/µm, which was on a larger scale than those reported in optical traps. As higher pressures were applied, the stiffness increased as well. The optical trap stiffness of human red blood cells was typically found to be a few tenths of piconewtons/nanometer, produced by the laser power of several hundred megawatts [16]. This confirmed our previous finding, that acoustic traps, requiring less energy in the low milliwatt range, may induce stronger forces than their optical counterpart.

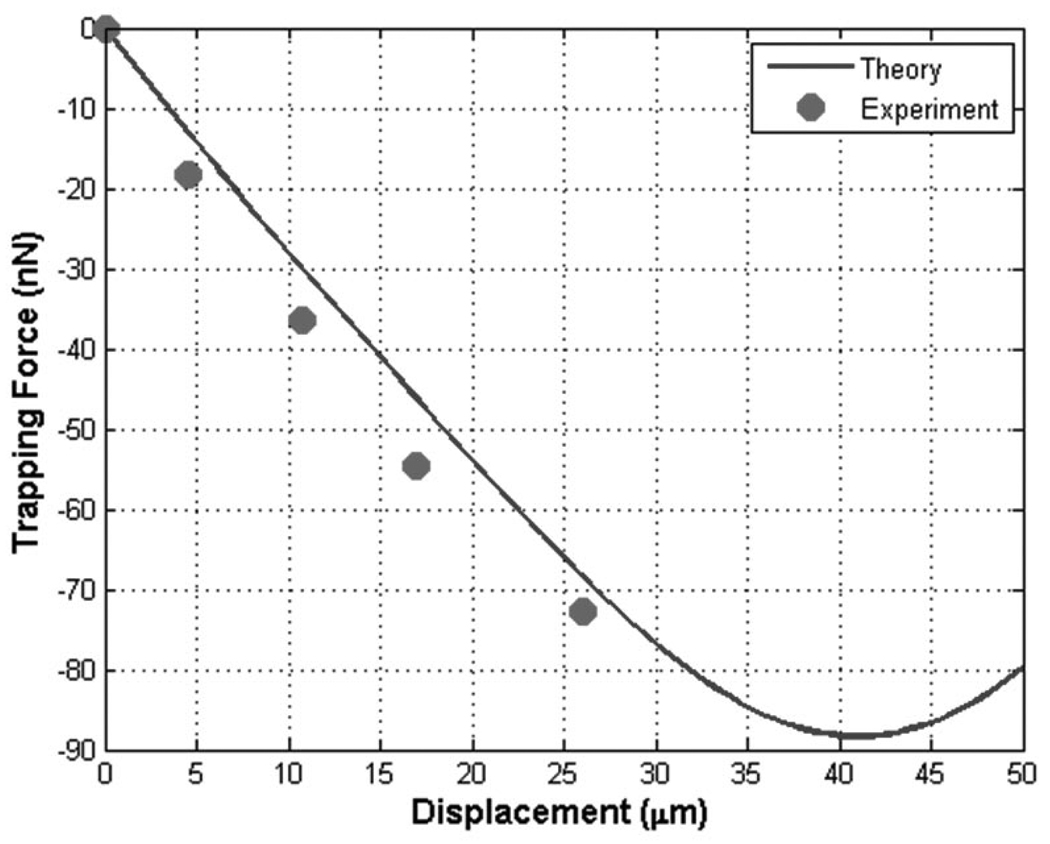

C. Comparison of Measured Data With Model Values

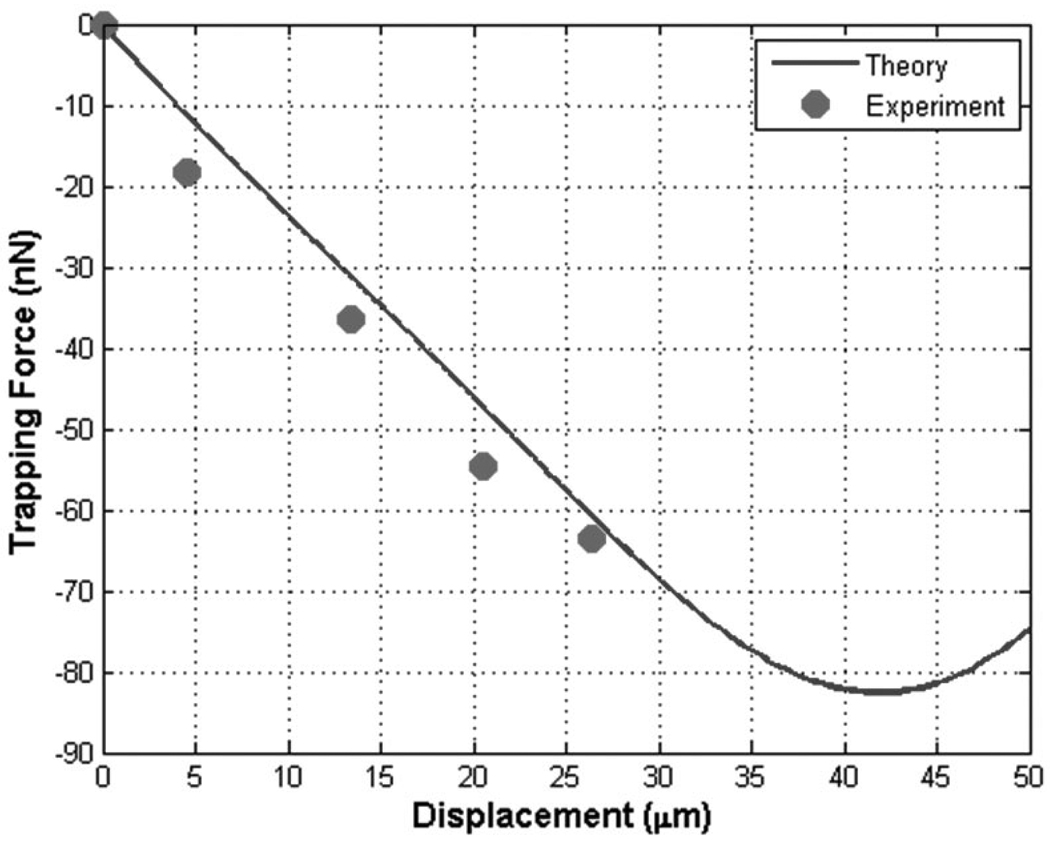

The calibrated forces were compared with the predicted values from the ray acoustics model. The analytical curves of trapping forces were displayed as the relative distance of the droplet from the fixed focus was transversely varied. When the transducer was driven at 33 MHz and 2.0 MPa, as shown in Fig. 8, the trapped droplet could be displaced as much as 26 µm, whereas the displacement was 41 µm in the model. The reason for such a large difference was that the current ray acoustics model did not consider the membrane property, namely its friction coefficient. The measured trapping force at that location was 73 nN, and its expected value was 68 nN. The trap stiffness was measured as 2.9 nN/µm, close to its analytical value of 2.7 nN/µm.

Fig. 8.

Comparison between theory and experiment: trapping force and trap stiffness at 33 MHz and 2.0 MPa. The measured stiffness was 2.9 nN/µm, compared with 2.7 nN/µm in theory.

Similarly, at 36 MHz and 1.8 MPa in Fig. 9, the droplet escaped from the trap at 26 µm, nearly the same as the previous case. The trapping force at that point was then 64 nN, and its theoretical result was 61 nN. The trap stiffness was measured to be 2.6 nN/µm, compared with 2.4 nN/µm in the model. Therefore, the measured data were in good agreement with its analytical results. The error might be caused by the surface friction between the membrane and the droplet, and the ambient vibration leading to inaccurate displacement trackings.

Fig. 9.

Comparison between theory and experiment: trapping force and trap stiffness at 36 MHz and 1.8 MPa. The measured stiffness was 2.6 nN/µm, compared with 2.4 nN/µm in theory.

IV. CONCLUSION

Two-dimensional trapping forces were calibrated against fluid drag forces of known magnitudes and directions. The measured forces were represented by a function of droplet displacement with respect to the trap center, and its magnitudes were in the range of tens of nanonewtons. Linear regressions were then conducted to estimate the trap stiffness in the range of a few nanonewtons per micrometer. The effect of the mylar membrane in the current experimental arrangement, which may distort the beam intensity around the trapped particle, was studied using FEA. The measured and theoretical results were in good agreement. Therefore, the acoustic trapping is shown to be capable of producing larger forces than those of optical tweezers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank S.-Y. Teh and Dr. A. Lee for droplet synthesis, and Dr. S. Sadhal for comments on fluid mechanics.

This work has been supported by NIH grants R21-EB5202 and P41-EB2182.

Biographies

Jungwoo Lee received his B.S. and M.S. degrees in electrical engineering from Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea, in 1995 and 1997, respectively. He obtained his Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, in 2006. From 1997 through 1998, he was an R&D engineer at Samsung Electro-Mechanics, Suwon, South Korea. Dr. Lee currently works as a research associate for the NIH Resource Center on Medical Ultrasonic Transducer Technology at the University of Southern California. His research interests include cell manipulation, sorting, and acoustic radiation force imaging using high-frequency ultrasound.

Changyang Lee received the B.S. degree in mechanical engineering from Kookmin University, Seoul, Korea, in 2002 and the M.S. degree in mechanical engineering from Korea University, Seoul, Korea in 2004. He worked in the Biomedical Science Center at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology from 2002 to 2008 as a researcher. He is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering at the University of Southern California under the direction of Prof. K. Kirk Shung. His research interests include biomedical applications using high-frequency ultrasound and cell mechanobiology.

K. Kirk Shung obtained a B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Cheng-Kung University in Taiwan in 1968, an M.S. degree in electrical engineering from University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, in 1970 and a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from University of Washington, Seattle, WA, in 1975. He did postdoctoral research at Providence Medical Center in Seattle, WA, for one year before being appointed a research bioengineer holding a joint appointment at the Institute of Applied Physiology and medicine. He became an assistant professor at the Bioengineering Program, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA in 1979 and was promoted to professor in 1989. He was a Distinguished Professor of Bioengineering at Penn State until 2002 when he joined the Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, as a professor. He has been the director of NIH Resource on Medical Ultrasonic Transducer Technology since 1997.

Dr. Shung is a Fellow of IEEE, the Acoustical Society of America, and the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. He is a founding fellow of the American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering. He has served for two terms as a member of the NIH Diagnostic Radiology Study Section. He received the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Early Career Award in 1985 and was the coauthor of a paper that received the best paper award for the IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control (UFFC) in 2000. He was selected as the distinguished lecturer for the IEEE UFFC society for 2002–2003. He was elected an outstanding alumnus of Cheng-Kung University in Taiwan in 2001. In 2010 he received the Holmes Pioneer Award in Basic Science from American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine.

Dr. Shung has published more than 300 papers and book chapters. He is the author of a textbook, Principles of Medical Imaging, published by Academic Press in 1992 and a textbook, Diagnostic Ultrasound: Imaging and Blood Flow Measurements, published by CRC Press in 2005. He co-edited a book, Ultrasonic Scattering by Biological Tissues, published by CRC Press in 1993. Dr. Shung’s research interest is in ultrasonic transducers, high-frequency ultrasonic imaging, ultrasound microbeams, and ultrasonic scattering in tissues.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashkin A, Dziedzic JM, Bjorkholm JE, Chu S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt. Lett. 1986;vol. 11(no. 5):288–290. doi: 10.1364/ol.11.000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. Overstretching B-DNA: The elastic-response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 1996;vol. 271(no. 5250):795–799. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kojima H, Muto E, Higuichi H, Yanagida T. Mechanics of single kinesin molecules measured by optical trapping nanometry. Biophys. J. 1997;vol. 73(no. 4):2012–2022. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78231-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visscher K, Block SM. Versatile optical traps with feedback control. Methods Enzymol. 1998;vol. 298:460–489. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)98040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg-Søensen K, Flyvbjerg H. Power spectrum analysis for optical tweezers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2004;vol. 75(no. 3):594–612. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felgner H, Muller O, Schliwa M. Calibration of light forces in optical tweezers. Appl. Opt. 1995;vol. 34(no. 6):977–982. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.000977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Teh SY, Lee AP, Kim HH, Lee C, Shung KK. Single beam acoustic trapping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;vol. 95(no. 7) doi: 10.1063/1.3206910. art. no. 073701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Teh SY, Lee AP, Kim HH, Lee C, Shung KK. Transverse acoustic trapping using a Gaussian focused ultrasound. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2010;vol. 36(no. 2):350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashkin A. Optical trapping and manipulation of neutral particles using lasers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;vol. 94(no. 10):4853–4860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkin A. Forces of a single beam gradient laser trap on a dielectric sphere in the ray optics regime. Biophys. J. 1992;vol. 61(no. 2):569–582. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81860-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwan H. Biological Engineering. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marston P. Negative axial radiation forces on solid spheres and shells in a Bessel beam. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007;vol. 122(no. 6):3162–3165. doi: 10.1121/1.2799501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Shung KK. Radiation forces exerted on arbitrarily located sphere by acoustic tweezer. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;vol. 120(no. 2):1084–1094. doi: 10.1121/1.2216899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svoboda K, Block SM. Biological applications of optical forces. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1994 Jun;vol. 23:247–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Neill ME. A sphere in contact with a plane wall in a slow linear shear flow. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1968;vol. 23(no. 11):1293–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Wen C, Xie H, Ye A, Yin Y. Mechanical property analysis of stored red blood cell using optical tweezers. Colloid. Surf. B. 2009;vol. 70(no. 2):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]