Introduction

Back pain is the second most common complaint reported by patients visiting their primary care physician [1] and the most frequent complaint of individuals seen by orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, and occupational medicine physicians [2]. It is the leading cause of physical disability among adults, and approximately 2% of the population is disabled because of spine problems and related pain in any given year [3,4]. The total national expenditure for the care of low back pain (LBP) is estimated at greater than 90 billion dollars per year in the United States alone [5]. Although the proportion of all physician visits related to back pain remained relatively stable from 1998 to 2002 [6], the use of local anesthetic injection as a tool in diagnosing and treating spinal pain rose sharply [31].

Bupivacaine is an amide used as a local anesthetic. Its uses include infiltration, nerve block, epidural, and intrathecal anesthesia. Bupivacaine often is administered to control pain by local, epidural or spinal injection before, during and after spinal surgery [7,8]. Therapeutic concentrations commonly used are 0.1%, 0.25%, and 0.5% bupivicaine typically injected at about 4cc for an epidural but vary greatly with the application and location of the injection (e.g. intradiscal or intraarticular). It also is commonly injected locally to reduce disabling chronic low back pain associated with intervertebral disc degeneration. Bupivacaine, rather than lidocaine, is used for diagnostic procedures and treatment of spine-related pain because it provides a long duration of neural blockade and has less motor effect and neurotoxicity than lidocaine when administered intrathecally at equivalent doses in rat models [9].

Although bupivacaine has been used extensively for pain control, it is also cardiotoxic, neurotoxic, and the most myotoxic of the local anesthetics [10]. Recent studies demonstrated that bupivacaine (0.5%) is toxic to cartilage and chondrocytes. Specifically, in vitro exposure of bovine articular cartilage (AC) and articular chondrocytes to 0.5% bupivacaine solution resulted in cytotoxicity after only 15–30 minutes of exposure [18]. Other studies report intra-articular bupivacaine results in histopathologic change and chondrotoxic effects in rabbit joints [11–13]. Also emerging is an increasing number of case reports of patients experiencing complete chondrolysis of the shoulder and knee after bupivocaine infusions [20, 29]. Recently bupivacaine was also reported to decrease viability of rabbit and human disc cells to an even greater extent than that observed with articular chondrocytes [14].

The extent of bupivacaine cytotoxicity to a particular tissue is determined largely by its local concentration and the duration of exposure. The avascular nature of the intradisc space could potentially prolong the effective half-life of bupivacaine and thereby increase toxicity even after a single injection. Recent evidence indicates that epidural injection of contrast agent using a transforaminal approach leads to penetration of the dye into the disc annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) [22]. This suggests the possibility of exposing disc cells to anesthetics during diagnostic procedures. Thus it is imperative to determine if bupivacaine is indeed toxic to intervertebral discs under physiological conditions to prevent potential contribution to disc degeneration through the administration of anesthetic.

Prior studies measuring the toxicity of bupivacaine used primary cells isolated from intervertebral discs [14]. Culturing these cells in alginate beads allows them to maintain chondrocyte-like polygonal morphology similar to their morphology in vivo. However, alginate beads and monolayer cultures are unable to mimic the structural matrix in which disc cells reside in vivo. Hence the physiological relevance of these in vitro cell culture studies has been questioned. Therefore the goal of this study was to examine the effect of bupivacaine on cell viability using a disc organ model system that approximates the in vivo matrix architecture. In addition, a key metabolic function of disc cells is to produce extracellular collagen and proteoglycan matrix. Thus in addition to cytotoxicity, these important endpoints were measured to determine the effect of bupivacaine on disc cell function.

Materials and methods

Isolation of functional spine units (FSUs) from mouse spine and disc culture

The whole spine was surgically harvested from 10 week-old mice in an f1 background of C57Bl/6:FVB/n immediately after euthanization by CO2 asphyxiation. This f1 background was used so that the mice are genetically identical but do not have any pathologies characteristic of inbred strains. FSUs consist of two vertebrae surrounding one disc. The superior endplate of the upper vertebra and the inferior endplate of the lower vertebra were removed. FSUs were cultured in 5 ml Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium/F12 (1:1) media with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Invitrogen) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Testing integrity of FSUs organotypic culture model system

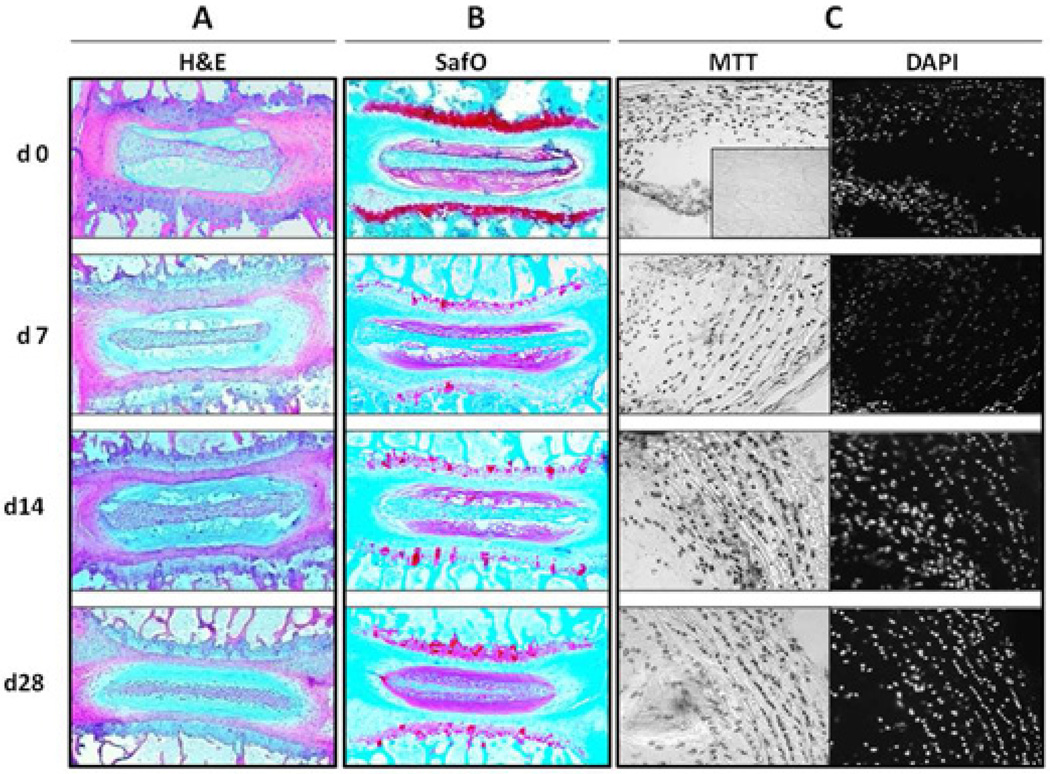

The FSUs were cultured for 0, 7, 14 or 28 days. Changes in histology were assessed by staining 7 µm paraffin-embedded sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or safranin O/fast green dyes (Fisher Scientific) by standard methods and imaging at 40–200× magnification (Nikon Eclipse Ts100). Histological assessments include microscopic inspection of cell density within the annulus fibrosis, nucleus pulposus, and endplate, proteoglycan content by safranin O staining intensity, annular lamella organization, and endplate structural integrity. No systematic grading system was employed as these were qualitative evaluations. Histological analyses on the discs of three mice at each time point were performed by two researchers in a non-blinded fashion. Cell viability was examined by MTT assay (below), and collagen and proteoglycan matrix syntheses were measured by radiolabel incorporation assays (below).

Bupivacaine exposure of mouse disc organotypic cultures

Three to four FSUs were cultured for 3 days in 5 ml of media in a 6-well plate prior to drug exposure to equilibrate after surgical trauma, which might trigger the release of inflammatory cytokines that affect overall disc cell metabolism. On day 3, FSUs were transferred to a 24-well plate containing 1 ml of bupivacaine (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) or 0.9% saline as a vehicle control. FSUs were exposed for 0, 30, 60 or 120 minutes to 0.5% bupivacaine or saline. To determine if there is a dose-dependent effect, FSUs were exposed to 0.1%, 0.25%, or 0.5% bupivacaine for 60 minutes.

MTT assay for cell viability (16)

After bupivacaine exposure, FSUs were incubated for 2 hours in 500 µl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, 1mg/ml) in a 48-well plate at 37°C and 5% CO2. Only viable cells are able to convert MTT into a purple precipitate. Live cells stain dark purple while dead cells appear yellowish. Frozen cross-sections (7 µm) of the disc were prepared to quantitated viable positively stained viable cells and stained with the nuclear fluorescent dye DAPI to determine total cell number. Sections were imaged using a Leica DM5000 fluorescent microscope and the results reported as the percent cell death (the number of dead cells/total cell number).

Determination of matrix protein synthesis

After 2 hour exposure to bupivacaine, 4 lumbar FSUs were cultured for 3 days in 0.5 ml of F-12/DMEM containing 10% FCS, 1% PS, and 25 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid in a 48-well plate in the presence of 20 µCi/ml 35S-sulfate (to measure proteoglycan synthesis) and 10 µCi/ml 3H-L-proline (to measure collagen synthesis) at 37°C. Individual discs were dissected from the FSUs under a 5X lens. The discs were then ground using a micropestle in a 1.5 ml microfuge tube (USA Scientific) in 0.1 ml homogenizing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 100 mM glycine, 0.1% Triton×100, 50 µM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor) with 4M guanidine-HCl and extracted for two days with rotation at 4°C. Proteoglycan synthesis was assayed using the size exclusion PD-10 column to partition incorporated 35S-sulfate from free radiolabels [17]. Collagen synthesis was determined by the collagenase-sensitive assay as previously described [17,18]. Rates of collagen and proteoglycan synthesis were calculated as picomoles of incorporated sulfate (PG) or L-proline (collagen) per µg DNA per hour.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was done using discs isolated from three mice, and duplicates were performed for each mouse disc specimen. All data were reported as mean of three independent experiments ± standard error and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated to determine significance based on independent two-sample t test for each comparison.

Results

Disc organotypic culture model system

The integrity of the intervertebral discs in this organotypic culture system was assessed histologically after increasing duration of ex vivo culturing up to 28 days. H&E staining of sections of functional spine units (FSUs including 2 vertebrae surrounding 1 intervertebral disc) revealed no major structural changes in the disc organs at days 7, 14, or 28 compared to day 0 (Fig 1A). Safranin O staining also showed little change in the intensity of the nucleus pulposus (NP) staining, suggesting minimal change in the proteoglycan matrix with increasing time ex vivo (Fig 1B). However there was reduced staining in the growth plate, indicating some PG loss in this region. MTT assay showed that the number of viable cells did not significantly change up to 28 days in culture (Fig 1C). As control, discs incubated in serum free media at 4 °C for two weeks showed drastic loss in safranin O staining, considerable matrix disorganization, and a complete loss viable cells and matrix synthesis capability (data not shown). Hence, this organotypic culture model retains robust cellular and tissue integrity for a period of at least one month.

Figure 1. Histological features and cell viability in disc organotypic culture.

Disc structure remains intact after 28 days in organtotypic culture (A) as assessed by H&E staining and (B) Safrinin ) staining indicates minimal loss of PG in the nucleus pulposus (NP), but substantial loss in the growth plates (GP) even by 7 days (arrow). (C–D) MTT assay on FSU sections revealed no decline in cell viability at any of the time-points. The inset shows a positive control using dehydrated disc tissue to induce complete cell death. AF, annulus fibrosus.

In addition to maintaing viability, cells in this organotypic culture model remained metabolically active. One key function of disc cells is to synthesize matrix constituents. This was tested by measuring the incorporation of radiolabeled sulfur into proteoglycans and L-proline into collagen. Although total protein synthesis was slightly decreased after 14–28 days in culture, neither PG nor collagen synthesis was significantly affected after 28 days of culture (Fig. 2). For example, collagen syntheses at day 0 and day 28 of culture were 4.8 and 4.3 pmole/ng DNA, respectively. Proteoglycan synthesis slightly increased after 28 days (4.7 pmoles/ng DNA) as compared to day 0 (3.2 pmoles/ng DNA) of culture.

Figure 2. Matrix synthesis of disc organotypic culture.

Synthesis of proteoglycan synthesis (35S-sulfate incorporation) and collagen (35H-proline incorporation) by FSUs after being cultured for 0, 7, 14 or 28 days were determined as described in Material and Method. PG synthesis (fmoles 35S-sulfate/ng DNA) showed no change after 14 days and a slight increase after 28 days. Collagen synthesis (fmoles 35H-proline/ng DNA) remained constant during 28-day culture period. Values shown are averages of three independent trials + SE.

Time- and dose-dependent effects of bupivacaine on the cell viability

To test the effects of bupivacaine on cell viability, FSUs were exposed to bupivacaine at different concentrations and for different periods of time, and the cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Approximately 20% of the cells died after 1 hour of exposure to 0.5% bupivacaine, and this increased to about 70% after 2 hours of exposure (Fig 3). Mouse disc cells also showed a dose-dependent decrease in viability upon exposure to bupivacaine. Incubation in 0.25% bupivacaine for one hour resulted in about 25% cell death while 0.5% bupivacaine caused 60% cell death. The increased percent cell death with increasing percent bupivacaine was statistically significant. The CIs were 6.3–46.1% at 0.25% bupivacaine and 53.2–70.1% at 0.5% bupivacaine, respectively. These results demonstrate a time- and dose-dependent cytotoxic effect of bupivacaine on disc cells under conditions that mimic therapeutic doses and physiological structural matrix environment.

Figure 3. Time- and dose-dependent effect of bupivacaine on disc cell viability.

Top, MTT staining of disc sections from FSUs exposed to bupivacaine or saline vehicle control. Black spots reveal viable cells and the insets stained with DAPI reveal the total cell number. Bottom, the percent cell death as a function of bupivacaine concentration (left) and time of exposure (right). Values are shown averages of six independent experiments + SE. Statistical significance (asterisk) was noted at 30, 60, and 120 minutes (Bottom Right) as well as in comparing each concentration (Bottom Left). NP, nucleus pulposus.

Effects of bupivacaine on disc matrix synthesis

Because a key function of disc cells is matrix synthesis, the effects of bupivacaine on collagen and proteoglycan synthesis was measured. No significant changes in PG synthesis were observed at low doses (<0.25%) of bupivacaine. At 0.5% bupivacaine PG synthesis was reduced three-fold (Fig. 4). Similarly, collagen synthesis was slightly decreased (~75% of untreated control) at 0.25% bupivacaine and four-fold at 0.5% bupivacaine exposure. These results demonstrate that therapeutic levels of bupivacaine affect disc matrix synthesis. Because the data were normalized to total DNA, which might include those persisted from dead cells, the decrease of PG and collagen syntheses may be due to a decrease of live cells, not the decrease in production matrices per cell.

Figure 4. Dose-dependent effects of bupivacaine on matrix synthesis.

Matrix synthesis by disc organotypic culture done by dual labeling with 35S-sulfate and 3H-L-proline. Synthesis was quantified as the amount of incorporated radiolabel per unit DNA (fmoles 35S-sulfate/ng DNA for proteoglycan, and fmoles 35H-proline/ng DNA for collagen). Y axis, matrix synthesis as the percent of untreated control. Bupivacaine exposure did not affect PG synthesis except at a concentration of 0.5% (Black bars). Collagen synthesis was affected at a concentration of 0.25% or greater (Gray bars). Values shown are averages of three independent trials + SE. Statistical significance (asterisk) was noted at 0 and 0.5% bupivacaine for both collagen (Col) and proteoglycan (PG) synthesis.

Discussion

In the past decade, several disc organotypic culture systems were developed [23–27]. These have several advantages over monocultures of cells for assessing the impact of environmental factors, including drugs, on tissues. The most obvious benefits include better mimicking endogenous exposure levels and responses of complex tissues with heterogenous cell types and distribution. For all organ cultures, it is critical to optimize conditions such that cells have access to the proper nutrients ex vivo. Critical parameters for intervertebral discs is their geometry and size because cell metabolism depends primarily on diffusion for nutrient and waste exchange. Discs from smaller animal models, including murine and lapine, yield cell viability >80% through four weeks of culture ex vivo [23, 24]. In contrast, larger animal models only tolerate shorter durations (6 hours to 3 weeks) due to limitation of diffusion through larger discs [25–27]. In attempt to prolong viability through convective transport and to mimic the physiologic mechanical environment, researchers have applied static and dynamic compression in bovine, ovine, and lapine models [25–27]. Lee et al. demonstrated the need to remove end plates to maintain adequate cell viability in larger models [25]. End plate removal mandates compressive loading or osmotic manipulation of media to control swelling [26].

Although mouse disc organotypic cultures have been previously reported [32, 33], these were performed using coccygeal intervertebral discs in short termed culture (1–5 days) with little or no assessment of cell viability or metabolic activity. In our mouse lumbar disc organ model, with preservation of the end plates and adjacent vertebral bodies, in an unloaded state, maintain cell viability for four weeks, a time frame similar to that reported by Lim [23] and Haschtmann [24]. This offers an important advantage for experiments that require long culture duration. More importantly, functional measurements such as proteoglycan and collagen syntheses can be measured via isotope labeling using this small organotypic culture system. Even with the retention of adjacent structures such as endplates and vertebrae, measurement of matrix synthesis is possible because of the small distance required for diffusion of 35S-sulfate and 3H-L-proline into the disc.

Mouse lumbar discs were recently reported to be proportionally and geometrically most similar to human discs compared to other animal models including [21]. Mouse lumbar motion segments also exhibit mechanical properties such as compression and torsion stiffness similar to those of humans, providing further validation of mice as a good mechanical model of human discs [22]. Other obvious benefits of using mice include the availability of commercial research reagents (e.g., antibodies) ease of surgical methods, the mouse genome and extensive biologic literature. Nevertheless, mice are not human and several notable distinctions exist in the biology of the discs between the two species, including differences in nutrient diffusion due to disparity in disc size, the nature of the quadruped vs. biped biomechanics, and the persistent presence of notorchordal cells in mouse discs. In addition, the absence of physiologically motivated loading and the order-of-magnitude difference in size between mouse and human exist as limitations of the murine model. Hence, mouse to human extrapolation of disc research observations need to be done with awareness of these limitations.

This study utilizes a mouse disc organotypic culture system to assess whether bupivacaine is toxic to this tissue at therapeutic doses, although it should be noted that depending on the site and how the injection is done these doses do not necessarily reflect the true local concentration experienced by the resident cells under clinical setting. The anesthetic reduces disc cell viability in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig 3), which corroborates the finding previously reported using a cell culture model system. This study also demonstrates for the first time that bupivacaine exposure also interferes with disc cell function in their native matrix context. Specifically, both collagen and proteoglycan synthesis were significantly decreased post-exposure at 0.5% bupivacaine, a dose used clinically for pain-relief. Maintenance of the integrity of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is critical to the health of intervertebral discs and indeed the spine. Loss of ECM and functional cells are two critical factors contributing to interverterbral disc degeneration (IDD). Bupivacaine exposure negatively affects both of these parameters. Clinically it is conceivable that bupivacain-induced cell death is irreversible unless the viable cells are able to divide to replace the dead ones after injection. A consequence of cell death is decreased cell number and hence decreased matrix synthesis. On the other hand, cells affected by bupivacaine but are still viable might be able to revert back to their normal metabolic state once the drug is worn off, but this conjecture requires further experimental verification. Hence, how well the disc recovers from clinical bupivacaine-induced cytotoxicity after the injection depend on the dose and frequency of injection, and it least likely to recover in the extreme cases of continuous infusion.

Bupivacaine is a commonly used anesthetic for pain control in low back pain and spinal surgery at concentrations ranging from 0.1–0.5% and in some cases up to 1% [28]. Bupivacaine binds to the intracellular sodium ions and blocks sodium influx into nerve cells, which prevents depolarization. In addition, bupivacaine is also a potent uncoupler of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and therefore may induce apoptosis [19]. Indeed, a previous study demonstrated that a fraction of cell death caused by bupivacaine is via apopotosis, although the main mechanism is through necrosis [14]. How bupivacaine causes cell death via different mechanisms remains to be investigated.

It should be noted that our in vitro experimental findings do not necessarily reflect those in the clinical settings. Whether permanent harm to the disc could result from a single or multiple injections of bupivacaine depends on the volume and concentration used, degenerative stage of the disc, how the injection is given…etc., all of which require further careful and systematic investigation. Nevertheless, bupivacaine cytotoxicity uncovered from this and other studies suggest that caution should be taken, especially in the cases of continuous infusion by using the so called pain pumps which are currently being developed for therapeutic treatment of low back pain and joint pain [20, 29, 30].

Conclusions

Harmful effects of bupivacaine on several cell types, including NP and AF cells, both in cell and disc organ models, have now been demonstrated. Bupivacaine dramatically and negatively impacts disc cell viability and matrix metabolism, both of which strongly correlate to intervertebral disc degeneration. This was established in an organotypic culture system that mimics the endogenous tissue environment using therapeutic exposures of bupivacaine.

Table 1.

Experimental design and the number of mice used

| Experiments | Lumbar discs per experiment |

Duplicates per experiment (No mice) |

No of mice in three experiments |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Establishment of organotypic culture | Disc | Mice | |||

| 1. Histology | 3 | 1 mouse | 2 | 6 | |

| 2. Cell viability | 3 | ||||

| 3. Matrix synthesis (0, 14, 28 days) | 3×4 | 2 mice | 4 | 12 | |

| B. Bupivacaine effects on cell viability | Disc | Mice | |||

| 1. Time (5 time pts) | 5×2 | 3 mice | 6 | 18 | |

| 2. Dose (4 doses) | 4×2 | ||||

| C. Bupivacaine effects on matrix synthesis (4 doses) | Disc | Mice | |||

| 4×3 | 2 Mice | 4 | 12 | ||

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge K. Bell, H. Georgescu, and C Davies for their technical assistance as well as L. Duerring for her administrative assistance. This work was supported by the Albert B. Ferguson, Jr. M.D. Orthopaedic Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation and the UPMC Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. L.N. is supported by ES016114.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Physician office visits for low back pain. Frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine. 1995;20:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cypress BK. Characteristics of physician visits for back symptoms: A national perspective. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:389–395. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.4.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MD, McGhan WF. Treating back pain without breaking the bank. Bus Health. 1998;16:50–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelsey JL, White AA. Epidemiology and impact of low back pain. Spine. 1980;5:133–142. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo X, pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:79–86. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000105527.13866.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sice PJ, Chan D, MacIntyre PA. Epidural analgesia after spinal surgery via intervertebral foramen. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:378–380. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotilainen E, Muittari P, Kirvela O. Intradiscal glycerol or bupivacaine in the treatment of low back pain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1997;139:541–545. doi: 10.1007/BF02750997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakura S, Kirihara Y, Muguruma T, et al. The comparative neurotoxicity of intrathecal lidocaine and bupivacaine in rats. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:541–547. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000155960.61157.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan MM. Clinical anesthesiology. 4th ed. 2006. pp. 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CR, Izzo NJ, Papas NE, et al. In vitro exposure to 0.5% bupivacaine is cytotoxic bovine articular chondrocytes. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogan N, Erdem AF, Erman Z, et al. The effects of bupivacaine and neostigmine on articular cartilage and synovium in the rabbit knee joint. J Int Med Res. 2004;32:513–519. doi: 10.1177/147323000403200509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomoll AH, Kang RW, Williams JM, et al. Condrolysis after continuous intra-articular bupivacaine infusion: an experimental model investigating chondrotoxicity in the rabbit shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Sowa G, Vo N, et al. Effect of bupivacaine on intervertebral disc cell viability. Spine. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.08.445. article in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao CQ, Wang LM, Jiang LS, Dai LY. The cell biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. Aging Res Rev. 2007;6:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey L Korecki, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 February 1;33(3):235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Studer RK, Aboka AM, Gilbertson LG, et al. p38 MAPK inhibition in nucleus pulposus cells: A potential target for treating intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2007;32:2827–2833. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b757a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilberston L, Ahn S-H, Teng P-N, et al. The effects of rhBMP-2, rhBMP-12, and Ad-BMP-12 on matrix synthesis in human annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus cells. The Spine Journal. 2008;8(3):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun X, Garlid KD. On the mechanism by which bupivacaine conducts protons across the membranes of mitochondria and liposomes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19147–19154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mark A slabaugh, et al. Rapid Chrondrolysis of the Knee After Anterior Crudiate Ligament Reconstruction. JBJR Am. 2010;92:186–189. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connell GD, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM. Comparison of animals used in disc research to human lumbar disc geometry. Spine. 2007;32:328–333. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000253961.40910.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott DM, Sarver JJ. Young investigator award winner: validation of the mouse and rat disc as mechanical models of the human lumbar disc. Spine. 2004;29:713–722. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000116982.19331.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim TH, Ramakrishnan PS, Kurriger GL, Martin JA, Stevens JW, Kim J, Mendoza SA. Rat spinal motion segment in organ culture: a cell viability study. Spine. 2006;31(12):1291–1297. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000218455.28463.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haschtmann D, Stoyanov JV, Ettinger L, Nolte LP, Ferguson SJ. Establishment of a novel intervertebral disc/endplate culture model: analysis of an ex vivo in vitro whole-organ rabbit culture system. Spine. 2006 Dec 1;31(25):2918–2925. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000247954.69438.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CR, Iatridis JC, Poveda L, Alini M. In vitro organ culture of the bovine intervertebral disc: effects of vertebral endplate and potential for mechanobiology studies. Spine. 2006 Mar 1;31(5):515–522. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201302.59050.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korecki CL, MacLean JJ, Iatridis JC. Characterization of an in vitro intervertebral disc organ culture system. Eur Spine J. 2007 Jul;16(7):1029–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0327-9. Epub 2007 Feb 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jünger S, Gantenbein-Ritter B, Lezuo P, Alini M, Ferguson SJ, Ito K. Effect of limited nutrition on in situ intervertebral disc cells under simulated-physiological loading. Spine. 2009 May 20;34(12):1264–1271. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a0193d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derby Richard, Eek Björn, Lee Sang-Heon, Seo Kwan Sik, Kim Byung-Jo. Comparison of Intradiscal Restorative Injections and Intradiscal Electrothermal Treatment (IDET) in the Treatment of Low Back Pain. Pain Physician. 2004;7:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anakwenze OA, Hosalkar H, Huffman GR. Case Reports: Two cases of glenohumeral chondrolysis after intraarticular pain pumps. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 Jan 29; doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1244-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JW, Lim TH, Park JB. Intradiscal drug delivery system for the treatment of low back pain. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010 Jan;92(1):378–385. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994–2001. Spine. 2007;(16):1754–1760. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3180b9f96e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ariga K, Yonenobu K, Nakase T, Hosono N, Okuda S, Meng W, Tamura Y, Yoshikawa H. Mechanical stress-induced apoptosis of endplate chondrocytes in organ-cultured mouse intervertebral discs: An ex vivo study. Spine. 2003;28(14):1528–1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wako Masanori, Haro Hirotaka, Ando Takashi, Hatsushika Kyosuke, Ohba Tetsuro, Iwabuchi Sadahiro, Nakao Atsuhito, Hamada Yoshiki. Novel Function of TWEAK in Inducing Intervertebral. J Orthop Res. 2007 Nov;25(11):1438–1446. doi: 10.1002/jor.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]