Abstract

Background

Childhood maltreatment and early trauma leave lasting imprints on neural mechanisms of cognition and emotion. Using a rat model of infant maltreatment by a caregiver, we investigated whether early-life adversity leaves lasting epigenetic marks at the Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) gene in the CNS.

Methods

During the first postnatal week, we exposed infant rats to stressed caretakers that predominately displayed abusive behaviors. We then assessed DNA methylation patterns and gene expression throughout the life span, as well as DNA methylation patterns in the next generation of infants.

Results

Early maltreatment produced persisting changes in methylation of BDNF DNA that caused altered BDNF gene expression in the adult prefrontal cortex. Furthermore, we observed altered BDNF DNA methylation in offspring of females that had previously experienced the maltreatment regimen.

Conclusions

These results highlight an epigenetic molecular mechanism potentially underlying lifelong and transgenerational perpetuation of changes in gene expression and behavior incited by early abuse and neglect.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, child abuse, transgenerational inheritance, BDNF, Reelin, Prefrontal Cortex, Hippocampus

Introduction

Childhood abuse and neglect compromise neural structure and function, rendering an individual susceptible to later cognitive deficits (1–3) and psychiatric illnesses, including schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder (1–4). Clinical and experimental studies indicate that the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus may play a pivotal role in the cognitive deficits and aberrant emotional behaviors originating from early-life adversity (2, 4–7). Thus, it has been hypothesized that the stress-induced changes in behavior are attributable to changes in neural plasticity in these areas (5, 8). Indeed, key mediators of neural plasticity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, such as BDNF protein levels, expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits, and measures of synaptic long-term potentiation are strongly affected by early adverse experiences (5, 9–12).

Epigenetic modulation of gene transcription, a newly proposed substrate for regulating gene expression changes underlying neural plasticity, may likewise be affected by early-life adversity. Epigenetic modifications are most commonly regulated by either direct methylation of DNA or by posttranslational modifications of histones, both of which can either promote or repress gene transcription (13–16). In the CNS, DNA methylation has historically been viewed as a static process following neural development and cell differentiation; however, recent data continue to highlight the dynamic role of DNA methylation in gene regulation (17–20). Furthermore, there is growing evidence for the role of epigenetic modifications in support of adult cognition and emotional health. For example, recent work has provided support for epigenetic marking in neural and behavioral plasticity (14, 21–28). Using a mouse model of depression, it has been demonstrated that changes in BDNF gene expression following chronic adult stress are attributable to epigenetic modification of the BDNF gene in the hippocampus (29). Epigenetic modulation of gene transcription has also been implicated in the long-term impact of positive caregiver experiences on adult rat stress responses and maternal behavior (30). Specifically, adult patterns of DNA methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the hippocampus, which plays a pivotal role in mediating stress responses, are directly associated with the quality of maternal care received in infancy (30). Additionally, epigenetic dysregulation within the human prefrontal cortex and hippocampus continues to gain support as a likely factor in the etiology of mental illness (31–32). For example, S-adenosyl methionine (a methyl donor), DNA methyltransferases, and methylation of the Reelin promoter are increased in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients (33–34).

Thus, increased susceptibility to cognitive impairments and psychiatric illnesses in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment may reflect a lasting imprint of early maltreatment on epigenetic mechanisms regulating gene expression. Indeed seminal work supporting this hypothesis demonstrates that there is increased methylation of the human rRNA gene promoter that is correlated with reduced rRNA gene expression in the hippocampus of suicide victims with a history of childhood maltreatment (35). In this study we used a rat model of infant maltreatment to assess the possibility of a lasting impact of early-life adversity on DNA methylation, as a potential transcription-regulating mechanism mediating gene expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We used male and female pups (Long-Evans) obtained from our breeding colony. Mothers were housed in polypropylene cages with wood shavings, and kept in a temperature (20 °C) and light (12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 7:00 am) controlled environment with food and water continually available. Day of parturition was termed 0 days of age, and litters were culled to 5–6 males and 5–6 females on postnatal (PN) day 1. All behavioral manipulations and observations were performed during the light cycle. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures. For complete detail on methodologies, please see Supplementary Methods online.

Maltreatment Regimen

Using an adaptation of a method previously reported (36–37), rat neonates were exposed to either a stressed-abusive mother (maltreatment) or positive caregiving mother (cross-fostered care) 30 min daily during the first postnatal week (PN1-7). Additional littermates served as normal maternal care controls by remaining in the home cage.

DNA methylation and gene expression assays

Tissue was collected from the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in PN8, PN30, and PN90 male and female rats exposed to the maltreatment regimen. Methylation status was assessed via methylation specific real-time PCR (MSP) or direct bisulfite DNA sequencing PCR (BSP) on bisulfite-modified DNA (Chemicon or Qiagen), or via methylated DNA immunoprecipitation using an antibody against 5-methylcytosine (Epigentek). Primers were designed to target CpG sites within the promoter region of BDNF exon IV, downstream of a promoter region within BDNF exon IX, and both the promoter region and an intragenic region of Reelin. Real-time one-step RT-PCR was performed using primers designed for BDNF exon IV and total BDNF mRNA (exon IX) and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) for Reelin mRNA. Primer sets and the locations they amplify are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Drug treatment

A stainless steel guide cannula was implanted in the left lateral ventricle of male and female adults. Following the recovery period, animals were given a single daily infusion (2 μl volume, infusion rate of 1 μl/min) of zebularine (600 ng/μl in 10% dimethylsulfoxide, DMSO) or vehicle (10% DMSO in saline) over a 7 day period. Brains were removed 24 hr after the last drug infusion in order to assess DNA methylation and gene expression.

Maternal behavior in adults exposed to maltreatment paradigm

Adult females that had been exposed to maltreatment in infancy or their littermate controls were mated. Beginning 3 days prepartum and through 7 days postpartum, maternal behavior within the home cage was recorded. In a second set of adults that had been exposed to the maltreatment paradigm, within 12 hours of birth, the dam was removed from the cage, litters were culled to 10 pups, and 4 pups per litter were cross-fostered. On PN8, both native and cross-fostered pups (males and females) were rapidly decapitated and the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus were isolated and stored at −80 °C until processing for measurement of DNA methylation.

Statistical Analysis

The relative fold change between maltreatment and control samples for MSP and gene expression assays was assessed by the comparative Ct method (38–39). Differences in methylation and mRNA levels were analyzed by two-tailed one-sample t-tests and two-tailed unpaired t-tests when appropriate (male and female data were collapsed after no differences were found between the sexes). Differences in BSP data were analyzed by analysis of variance tests (two-way and three-way where appropriate) and either Bonferroni’s or Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests as indicated. Behavioral data were analyzed with two-tailed paired or unpaired t-tests when appropriate. For all analyses, significance was set at p≤0.05.

Results

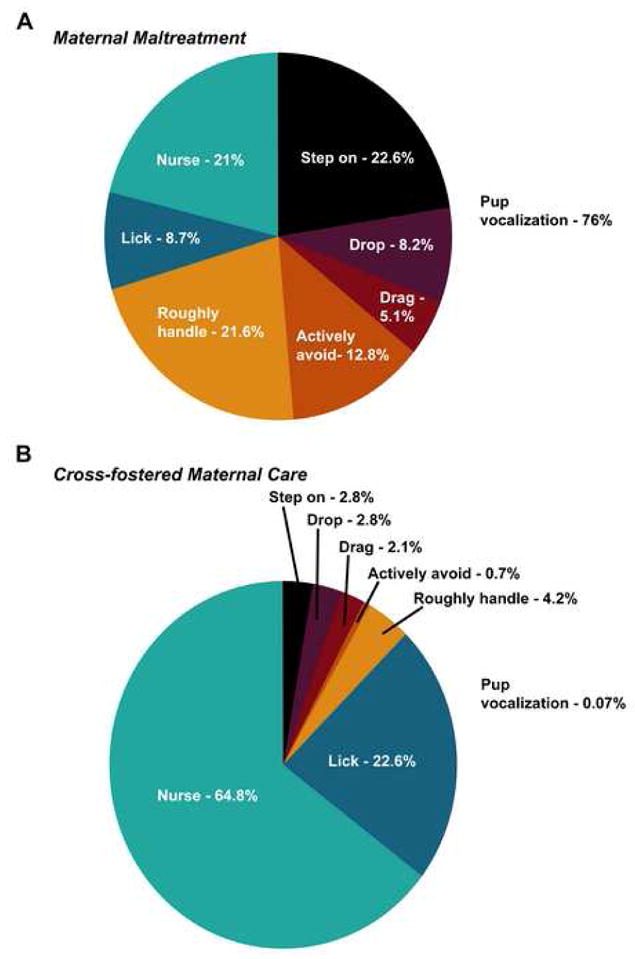

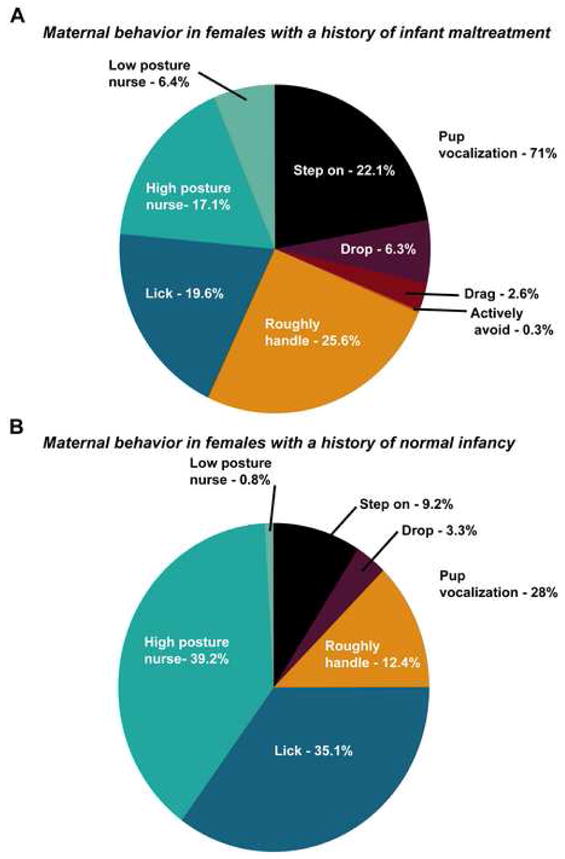

To model early maltreatment, we exposed infant male and female rats to a stressed, “abusive” mother 30 min daily during the 1st postnatal week (maltreatment condition). Mothers were stressed by providing limited nesting resources in an unfamiliar environment. Littermate controls were exposed to a non-stressed, positive caregiving mother (cross-fostered care condition; mothers were provided with abundant nesting resources in a familiar environment). As illustrated in Figure 1A, neonate pups within the maltreatment condition received significant amounts of abusive maternal behaviors, thus subjecting them to the experience of an adverse caregiving environment. During the maltreatment regimen, pups were frequently stepped on, dropped during transport, dragged, actively rejected, and roughly handled. Additionally, pups were often neglected. In contrast, neonates in the cross-fostered care condition rarely experienced behaviors classified as abusive, and received significant amounts of normal and positive caregiving behaviors (retrieval to the nest, licking, nursing), thus experiencing a positive caregiving environment (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Infants experienced an adverse caregiving environment.

(A) Qualitative assessment of the percent occurrence of pup-directed behaviors in the maltreatment condition indicates that pups experienced predominately abusive behaviors, which resulted in considerable audible pup vocalization. (B) In sharp contrast, pups experienced significant amounts of normal maternal care behaviors in the cross-fostered maternal care condition. Statistical analyses of the maternal behaviors (abusive versus normal care) are provided with Supplementary Figure 1.

Maltreatment during infancy decreases BDNF gene expression in the adult prefrontal cortex

It is well documented that both prenatal and postnatal adverse experiences yield a reduction in BDNF mRNA expression and BDNF protein levels that persists into adulthood (5, 10–11, 40–41). Importantly, aberrant BDNF gene expression continues to be implicated in the onset of several mental illnesses subsequent to early-life adversity (42-44). However, the mechanism by which lasting alterations in BDNF gene expression might be triggered is unclear. Thus, we sought to determine if early maltreatment might trigger lasting changes in BDNF DNA methylation as a transcription-regulating mechanism for BDNF gene expression changes.

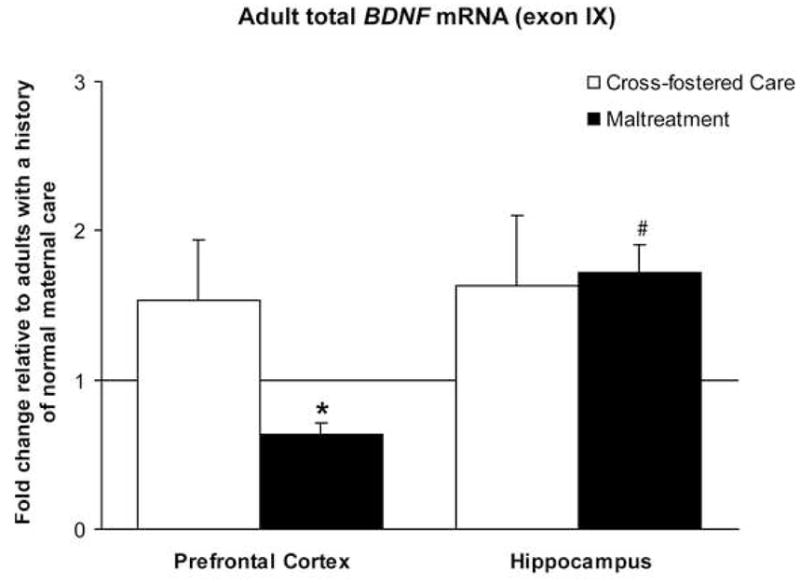

We first assessed BDNF total mRNA levels (exon IX) within the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of adult male and female rats that were exposed to the maltreatment paradigm as neonates. Figure 2 demonstrates that in the prefrontal cortex adult rats exposed to maltreatment during infancy had significant suppression of BDNF mRNA relative to both cross-fostered and normal maternal care controls. Though maltreatment produced a significant increase in mRNA levels in the hippocampus, maltreated-adults did not differ from cross-foster care controls (Figure 2). This suggests that the increase in the hippocampus was not exclusive to the experience of maltreatment, but also reflective of other variables, such as exposure to new caretakers, experience in a novel environment, and/or removal from the biological mother and home cage.

Figure 2. Maltreatment during infancy decreases BDNF gene expression in the adult prefrontal cortex.

Adult males and females exposed to maltreatment had less total BDNF mRNA (exon IX) in the prefrontal cortex than controls. Adults were derived from 5 mothers; n=7/group; *p-values significant versus both normal maternal care (t6=5.17, p=0.0021, one-sample t test) and cross-fostered controls (t12=2.19, p=0.0495, Student’s two-tailed t test). Maltreatment also increased levels of BDNF total mRNA in the hippocampus (t8=4.10, #p=0.0034, one-sample t test); however, maltreated-adults did not differ from cross-foster care controls; n=7–9/group. Error bars represent SEM.

Maltreatment during infancy elicits a lasting increase in BDNF DNA methylation in the prefrontal cortex

As we found deficits in BDNF gene expression within the adult prefrontal cortex specific to maltreatment, we next wanted to identify whether these patterns were correlated with lasting changes in BDNF DNA methylation, as global or site-specific methylation of CpG sites near and within regulatory regions of genes is often associated with transcriptional inactivity and gene suppression (13–16).

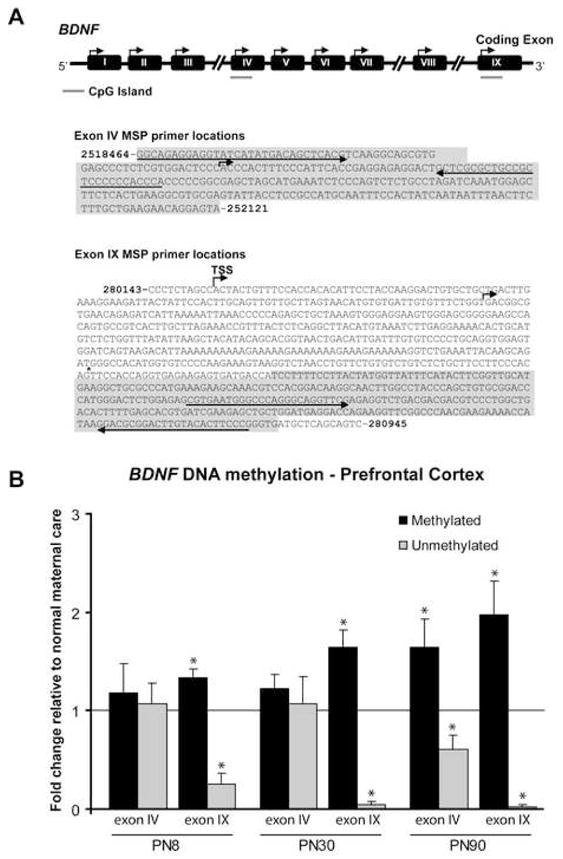

The BDNF gene contains nine 5′ non-coding exons (I-IXA), each linked to a unique promoter that differentially splices to the common 3′ coding exon IX (45–46). The activity of each non-coding promoter region dictates differential expression of BDNF exon-specific transcripts, providing tissue-specific and activity-dependent regulation of the BDNF gene across development and in adulthood (41, 45–47). To assess BDNF DNA methylation, we evaluated the region of exon IV (formerly rat exon III) encompassing the transcription start site and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element, as epigenetic regulation of this particular region continues to gain support for its pivotal role in neural activity-dependent BDNF gene expression (22, 29, 45, 48). We also evaluated a region of the common coding exon IX (formerly rat exon V) that encompasses a large number of CpG sites and is located downstream of a transcription start site for that exon. Expression of exon IV- and IX-containing mRNA transcripts gradually increases during postnatal development, particularly within the cortex and hippocampus (47, 49–50). Importantly, dynamic methylation of exon IV has been suggested to be a likely mechanism mediating BDNF gene expression during development, and thus susceptible to environmental insults (49).

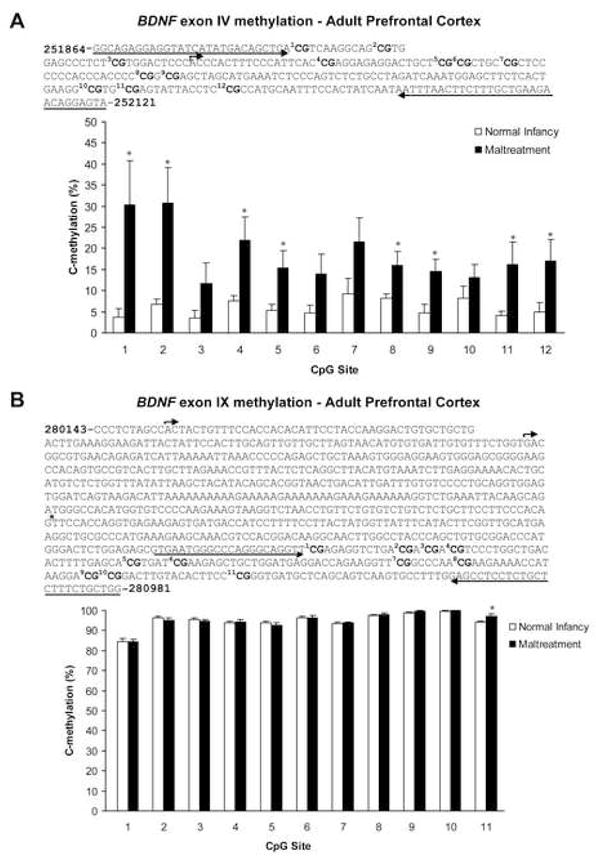

We first used methylation specific real-time PCR (MSP) to screen methylation of exon IV and IX DNA in the prefrontal cortex of male and female infants (PN 8), adolescents (PN30), and adults (PN90) that had been exposed to maltreatment or normal maternal care during the 1st postnatal week. Our MSP results demonstrate that early experiences trigger changes in BDNF DNA methylation within the prefrontal cortex that persist into adulthood (Figure 3). Specifically, at each age examined, maltreatment produced a significant increase in methylated BDNF exon IX DNA and a corresponding decrease in unmethylated BDNF exon IX DNA in comparison to both cross-fostered and normal maternal care controls. Furthermore, maltreatment-induced changes in methylation of exon IV were detected in adults. Thus, adults with a history of maltreatment showed significant methylation at both exons IV and IX DNA regions. We confirmed our MSP results for the adult prefrontal cortex via two approaches. First, we used direct bisulfite DNA sequencing PCR (BSP) to examine site-specific methylation of 12 CpG dinucleotides within the same region of exon IV screened by MSP. The results showed significant increases in methylation across the region in adults with a history of maltreatment (Figure 4A). We like-wise examined site-specific methylation of 11 CpG dinucleotides within the same region of exon IX screened by MSP. The results showed an increase in methylation only at site 11 with maltreatment (Figure 4B). Second, we used a methylated DNA immunoprecipitation assay (meDIP), which confirmed the increased presence of methylated BDNF DNA in our adult animals that had experienced the maltreatment regimen (Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, our data indicate that there were maltreatment-induced changes in methylation of BDNF DNA, and these changes were maintained through adolescence and into adulthood, even though the exposure to the abusive mothers ended at PN7.

Figure 3. Maltreatment during infancy elicits methylation of BDNF DNA in the prefrontal cortex.

(A) Schematic of the BDNF gene, with positions of CpG islands (in grey) relative to the transcription start site (TSS, indicated by the bent arrow) of exons IV and IX. Methylated primer pair positions for each exon are indicated by the left and right arrows, and primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1. (B) Methylation specific real-time PCR indicates that maltreatment results in methylation of BDNF DNA that persists into adulthood. For clarity of presentation, only the data generated in the abusive condition is illustrated. Experimental subjects (males and females) were derived from 13 mothers. n=4–9/group; *p-values significant versus normal maternal care (PN8 M p=0.0076, U p=0.0007; PN30 M p=0.0078, U p<0.0001; PN90 M(IV) p=0.0427, U(IV) p=0.0319, M(IX) p=0.0376, U(IX) p<0.0001; one-sample t tests) and cross-fostered controls (PN8 M p=0.0294, U p=0.0258; PN30 M p=0.0031, U p=0.0367; PN90 M p=0.0415, U p=0.0435; Student’s two-tailed t tests). Error bars represent SEM. PN=postnatal day; M=methylated; U=unmethylated.

Figure 4. Methylation analysis of individual CpG dinucleotides (BDNF exons IV and IX) from the prefrontal cortex of adults with a history of maltreatment or normal maternal care.

(A) Location of 12 CpG sites relative to the transcription initiation site (bent arrow) of exon IV. Note that this region of exon IV contains a cAMP response element site (TCACGTCA) for transcription factor cAMP response element binding protein, which encompasses CpG site 1. Sequencing primer pair positions are indicated by the left and right arrows, and primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Bisulfite DNA sequencing analysis indicates that maltreatment increases methylation of all CpG sites within the examined region of exon IV DNA in the adult prefrontal cortex (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc tests; significant effect of infant condition F=46.62, p<0.0001). n=7–8/group; *p-values significant versus controls (p 0.05). (B) Location of 11 CpG sites within the common coding exon (IX) relative to two transcription initiation sites (bent arrows) in promoter IXA. *major splice site; sequencing primer pair positions are indicated by the left and right arrows, and primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Bisulfite DNA sequencing analysis confirms that maltreatment during infancy results in site-specific methylation of exon IX DNA in the adult prefrontal cortex (n=9–11/group; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc tests), with a significant increase at CpG site 11 (p=0.0161). For both panels - error bars represent SEM. Male and female adults were derived from 7 mothers.

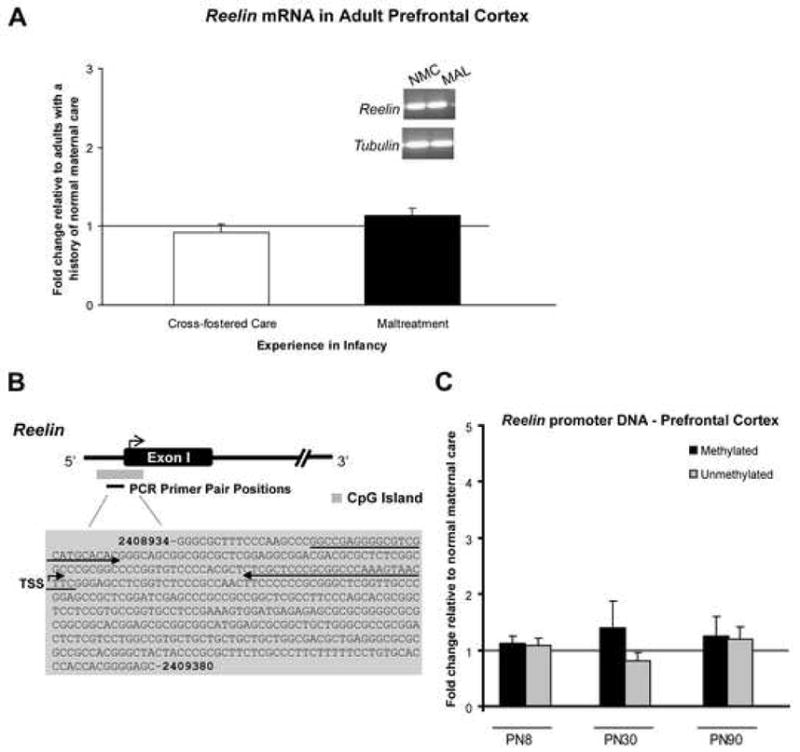

To determine whether such experiences produced similar changes in other genes, we also examined the methylation status of Reelin DNA within the prefrontal cortex. Reelin is another gene associated with neural plasticity and emotional health, and epigenetic regulation of the Reelin gene has been implicated in cognition and mental health (26, 33, 51). Although very little is known of how postnatal experiences affect Reelin gene regulation, what is known is that Reelin mRNA levels are higher in adults that as infants experienced abundant positive maternal behaviors (52). The effect of an adverse caregiving environment on transcriptional molecular mechanisms supporting Reelin gene expression is unknown. We first measured Reelin mRNA levels in the adult prefrontal cortex and found no difference between adults with either a history of maltreatment or normal infancy (Figure 5A). Using MSP, we failed to detect changes in methylation of DNA within the examined region of the Reelin promoter (Figure 5B–C). However, it is worth noting that we observed transient changes in Reelin DNA methylation in the cross-fostered care condition that may reflect environmental enrichment or learning of some sort (data not shown). This is in agreement with recent data that demonstrate the beneficial effect of environmental enrichment on chromatin remodeling (23).

Figure 5. Exposure to an adverse caregiving environment had no effect on Reelin gene expression or methylation of Reelin DNA.

(A) Maltreatment or cross-fostered care during infancy had no detectable effect on Reelin mRNA levels in the adult prefrontal cortex (n=8–10/group). Male and female adults were derived from 5 mothers. (B) Schematic of the large CpG island (in grey) relative to the transcription start site (TSS) of the Reelin gene (note that the entire CpG island is not represented, but only the portion relevant to the primer target region). Methylated primer pair positions are indicated by the left and right arrows, and primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1. (C) Exposure to the maltreatment condition had no observable effect on methylation of Reelin DNA within the prefrontal cortex. We also observed no changes in methylation of a CpG island located within an intragenic region of the Reelin gene (at location 2841591–2841823; data not shown). Male and female subjects were derived from 13 mothers; n=4–8/group. For panels A and C, error bars represent SEM. PN=postnatal day.

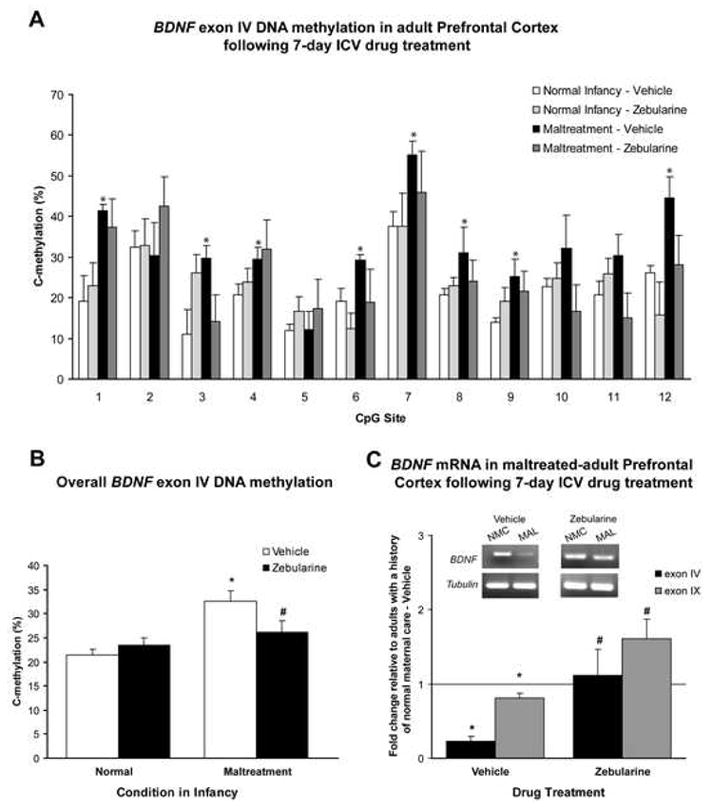

Maltreatment-induced deficits in BDNF gene expression in the adult prefrontal cortex are rescued by treatment with a DNA methylation inhibitor

Our studies support the hypothesis that experience-induced changes in adult BDNF gene expression could be due to changes in BDNF DNA methylation. To assess a causal relationship between maltreatment-induced changes in BDNF DNA methylation and BDNF mRNA expression in the adult prefrontal cortex, we chronically infused zebularine, a DNA methylation inhibitor, in male and female adults from our maltreatment regimen, and then assessed BDNF exon IV DNA methylation, as exon IV is the best-characterized target of epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene expression (22, 29, 45, 48). We also assessed BDNF exon IV mRNA levels as well as total BDNF mRNA levels (exon IX) following the drug treatment regimen.

The results indicate that zebularine treatment for seven days was sufficient to decrease methylation of BDNF exon IV DNA and rescue both BDNF exon IV mRNA and total mRNA levels in adults with a history of maltreatment (Figure 6). We note that there were differences in baseline methylation between vehicle-treated groups in Figure 6A and animals in Figure 4A. However, it is reasonable to ascribe these differences to any of several variables not present in the earlier experiment, including surgery for cannulation, daily handling of animals for drug infusions, and the 7-day infusion regimen. The precise mechanism of how zebularine is able to rescue aberrant methylation and gene expression in the adult CNS is not understood, but may do so by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases through its incorporation as a cytosine analog (53), or by actively demethylating DNA in non-dividing cells through a replication-independent event, such as DNA repair (19, 54–56). Nevertheless, we show that aberrant BDNF gene expression patterns induced by early experiences are reversible in the adult prefrontal cortex by pharmacological manipulation of DNA methylation, and at least one of the BDNF promoters responsible for this increase in gene expression is associated with exon IV.

Figure 6. Infusions of a DNA methylation inhibitor in the adult rescues maltreatment-induced deficits in BDNF gene expression in the prefrontal cortex.

(A) The effects of zebularine treatment on methylation of BDNF exon IV DNA (n=3–5/group; male and female adults were derived from 3 mothers). Maltreated animals infused with vehicle demonstrated significantly higher levels of methylation than controls, while zebularine treatment lowered levels of methylation in maltreated-animals (three-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc tests; significant effects of infant condition F=18.44, p<0.0001, CpG region F=7.69, p<0.0001, and infant condition × drug interaction F=6.73, p=0.0103). *p-values significant versus adults with a normal infancy infused with vehicle (p 0.05). (B) Average percentage of methylation across the examined CpG sites of exon IV in subjects from panel A (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc tests; significant effect of infant condition F=13.54, p=0.0003 and infant × drug interaction F=4.94, p=0.0273). *p-value significant versus adults with normal infancy (p<0.0001); #p-value significant versus maltreated-animals infused with vehicle (p=0.05). Maltreated-animals that received zebularine were not significantly different from normal controls. (C) The effects of zebularine treatment on mRNA (n=4–6/group). Animals with a history of maltreatment infused with vehicle demonstrated a significant decrease in both exon IV BDNF mRNA and total BDNF mRNA (exon IX). *p-values significant versus adults with a normal infancy infused with vehicle (exon IV t5=10.94, p=0.0001; exon IX t5=2.82, p=0.0373, one-sample t tests) or zebularine (exon IV t8=2.19, p=0.06; exon IX t9=2.29, p=0.0474, Student’s two-tailed t test). Zebularine treatment rescued the maltreatment-induced reduction in BDNF mRNA expression (exon IV t8=3.05, #p=0.0159; exon IX t10=2.91, #p=0.0156, Student’s two-tailed t test), and animals did not differ from normal maternal care controls. Agarose gel images represent total BDNF gene expression (IX). For all panels, error bars represent SEM. NMC=normal maternal care; MAL=maltreatment.

BDNF DNA methylation patterns in the prefrontal cortex incited by maltreatment are perpetuated to the next generation

Experiences in the nest provide a learning environment that serves to program the quality of maternal behavior that will be displayed toward the next generation. For example, infant rats reared without a mother display deficits in maternal behavior toward their own offspring, and the amount of licking rat neonates receive from the mother correlate with the amount of licking they will display toward their own offspring (57–59). In addition, rhesus macaques that were abused in infancy display maladaptive behaviors toward their own offspring (60–61). One brain area that may play a pivotal role in the programming of maternal behavior is the prefrontal cortex (58, 62–64). Given our findings of persisting maltreatment-induced changes in BDNF DNA methylation and gene expression in the prefrontal cortex, we hypothesized that adult females would display atypical maternal behavior toward their own offspring. As illustrated in Figure 7, females with a history of maltreatment (maltreated-females) displayed significant amounts of abusive behaviors toward their offspring, and these interactions resulted in audible pup vocalization. In the realm of normal maternal care behaviors, maltreated-females also frequently displayed low posture nursing positions. Thus, from our behavioral assessment we found that atypical maternal behavior correlated with the aberrant BDNF DNA methylation and gene expression patterns that we had observed.

Figure 7. Females with a history of maltreatment display aberrant maternal behavior toward their own offspring.

(A) Qualitative assessment of the percent occurrence of pup-directed behaviors in females with a history of infant maltreatment indicates that females display considerable abusive behaviors toward their first offspring. (B) In sharp contrast, females with a history of normal maternal care display predominately normal maternal care behaviors toward their first offspring. n=4–5/group, derived from 3 mothers. Statistical analysis of the maternal behaviors (abusive versus normal care) is provided with Supplementary Figure 3.

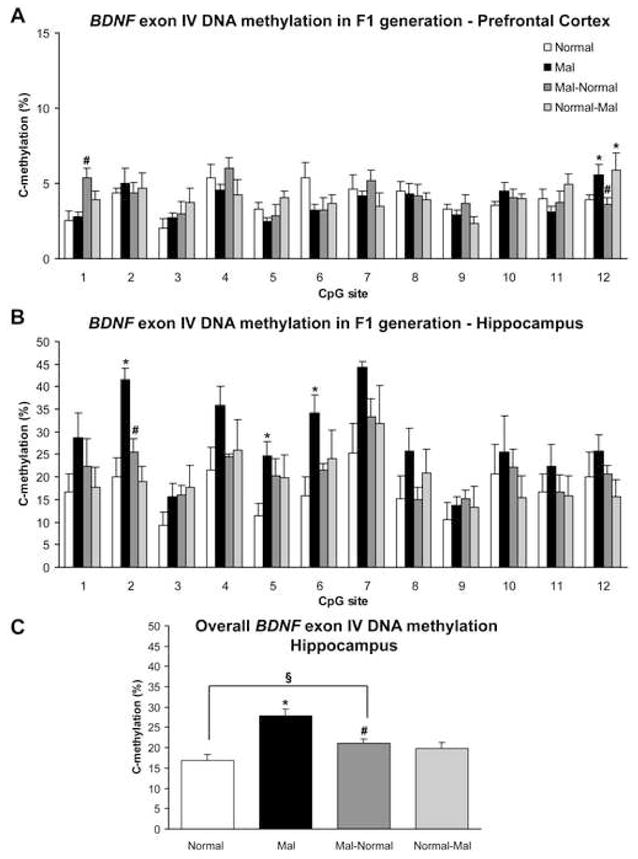

As our maltreated-females showed higher abusive behaviors toward their own offspring, we next sought to determine whether their offspring would also exhibit changes in methylation of BDNF DNA. Indeed, PN8 offspring (both males and females) derived from maltreated-females had significantly greater methylated BDNF DNA in their prefrontal cortex and hippocampus than offspring derived from normal-treated females (Figure 8, Supplementary Figures 4–5). Sequencing data indicated a site-specific increase in exon IV DNA methylation within the prefrontal cortex of offspring born to females with a history of maltreatment (Figure 8A). Although MSP failed to detect any changes in DNA methylation within the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 4A), sequencing data revealed significant increases in methylation at several CpG sites within the examined region of exon IV DNA (Figure 8B–C). Furthermore, sequencing also revealed site-specific increases in methylation of exon IX DNA in the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 5A). Overall, these data indicate that there is increased DNA methylation in the next generation.

Figure 8. Direct bisulfite sequencing confirms that DNA methylation patterns incited by maltreatment are perpetuated to the next generation, and that cross-fostering fails to completely rescue DNA methylation patterns.

(A) Sequencing reveals site-specific effects of mother history on methylation of exon IV DNA in offspring’s prefrontal cortex (two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s post hoc tests; significant effect of CpG site F=4.02, p<0.0001 and marginal effect of CpG site × mother history interaction F=1.45, p=0.06). At CpG site 12, offspring born to females with a history of maltreatment (Mal) have significant methylation in comparison to offspring from females with a history of normal infancy (*p=0.05). Cross-fostering mal-offspring to a female with a history of normal infancy (Mal-Normal) evokes an increase in methylation at CpG site 1 (#p-value significant versus mal and normal, p<0.01), while it reverses methylation at site 12 (#p-value significant versus mal, p=0.023). Cross-fostering normal offspring to a female with a history of maltreatment (Normal-Mal) is sufficient to increase methylation at site 12 (*p-value significant versus normal, p=0.05) (B) Sequencing detected significant methylation of exon IV DNA in the hippocampus of mal offspring (two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s post hoc tests; significant effect of CpG site F=5.21, p<0.0001 and mother history F=10.29, p<0.0001). *p-values significant versus normal, p<0.05. Cross-fostering (Mal-Normal) significantly reversed methylation at site 2 (#p-value significant versus mal offspring, p=0.04). (C) Average percentage of methylation across the examined CpG sites of exon IV in subjects from panel B (one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s post hoc tests; F=8.59, p<0.0001). *p-value significant versus normal, p<0.0001. Though cross-fostering (Mal-Normal) was able to reduce methylation (#p-value significant versus mal, p=0.004), methylation in these animals was still significantly higher than normal controls (p=0.034). Cross-fostering normal offspring to maltreated-females did not induce significant methylation. In all panels, n=3–8/group, derived from 7 mothers; error bars represent SEM.

To evaluate whether these changes were directly attributable to the postnatal environment, that is, the maternal behavior received, we cross-fostered offspring derived from maltreated-females to normal-treated females for the duration of the first postnatal week, and then assessed methylation of BDNF DNA at PN8. Sequencing data again indicated site-specific effects in methylation of exon IV DNA within the infant prefrontal cortex, with cross-fostering producing an increase in methylation at CpG site 1, yet a decrease at site 12 (Figure 8A). Likewise, there were site-specific effects in methylation of exon IX DNA in the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 5A). Finally, while there was an overall significant decrease in methylation of exon IV DNA within the hippocampus, cross-fostered offspring still had higher levels of methylation in comparison to normal controls (Figure 8B–C, Supplementary Figure 4B). Thus surprisingly, we failed to observe a complete rescue of the altered methylation patterns with cross-fostering. These data suggest that the perpetuation of maltreatment-induced DNA methylation patterns is not simply a product of the postnatal experience.

We also cross-fostered offspring derived from normal-treated females to maltreated-females for the duration of the first postnatal week, and then assessed BDNF DNA methylation at PN8. While sequencing did detect significant increases at both CpG site 12 of exon IV in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 8A) and CpG site 5 of exon IX in the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 5A), overall methylation levels did not significantly change (Figure 8B–C, Supplementary Figures 4C and 5B). These data again suggest that the perpetuation of methylation in this generation reflects another variable than postnatal experience.

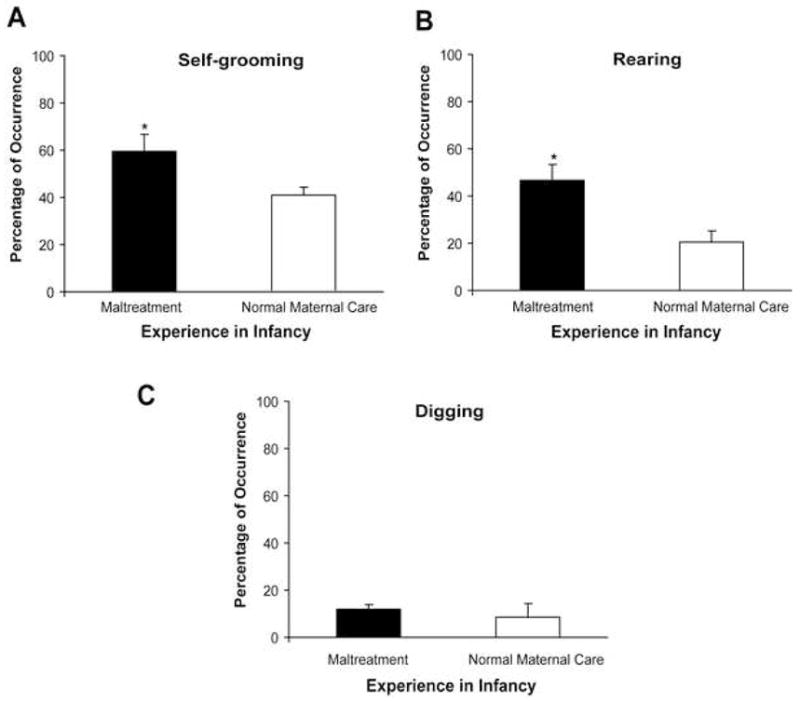

Since it is well-documented that stress experienced during gestation produces brain and behavioral alterations in offspring that are comparable to those produced by postnatal adversity (65–66), we wanted to document whether there were differences in prepartum behaviors between maltreated- and normal-treated females that may be indicative of stress and thus could influence fetal development. Our prepartum behavioral observations indicate that females with history of maltreatment displayed significantly more anxiety-related behaviors (excessive self-grooming and rearing) during this period (Figure 9). Though these are not direct measures of stress or the physiology of the prenatal environment, it is worthwhile to speculate that in addition to postnatal maltreatment, pups born to females with a history of abuse were potentially subjected to prenatal stress. Together, data suggest that the transgenerational perpetuation of maltreatment-induced changes in CNS DNA methylation is likely attributable to an interplay of both prenatal and postnatal experiences, and the hormonal environment in utero.

Figure 9. Females with a history of maltreatment display more anxiety-related behaviors during the prepartum period.

Assessment of behaviors 3 days prior to giving birth indicates that females with a history of maltreatment had increased (A) self-grooming and (B) rearing behaviors than females with a normal infancy. n=4–5/group; self-grooming t7=2.44, p=0.0448; rearing t6=3.12, p=0.0205; Student’s two-tailed t tests. (C) Digging behaviors were not affected by prior experience.

Discussion

Here we use a rodent model of infant maltreatment from a caregiver to explore the hypothesis that epigenetic modulation of gene transcription underlies the perpetuation of changes in gene expression incited by early-life adversity. First, we show that infant maltreatment results in methylation of BDNF DNA through the lifespan to adulthood that dovetails reduced BDNF gene expression in the adult prefrontal cortex. Second, we demonstrate that the altered epigenetic marks and gene expression in the adult can be rescued with chronic treatment of a DNA methylation inhibitor. Finally, we explore the perpetuation of maternal behavior and DNA methylation across a generation. We demonstrate that not only do rodents that have experienced abuse grow up and mistreat their own offspring, but that their offspring also have significant DNA methylation. To summarize, our results demonstrate a surprising robustness to the perpetuation of changes in BDNF DNA methylation both within the individual across its lifespan and in passing that altered methylation from one generation to the next.

It is clear that early social experiences and experience-related changes in neural correlates of cognition and emotion play a pivotal role in transgenerational transmission of phenotype, and particularly of maternal behavior. Recent support for the existence of transgenerational inheritance in mammals suggests that the epigenetic status of particular genes in the previous generation influences the next generation (57, 67–72). Indeed, transmission of positive aspects of maternal behavior, as well as adult stress responses, appears attributable to the methylation status of the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the hippocampus of the mother, as well as the methylation status of the promoter of the estrogen receptor alpha in the medial preoptic area (57, 67–68, 72). With the results presented here, we now provide the first evidence of perpetuation of maltreatment-induced changes in DNA methylation across a generation. The impact of these inherited DNA methylation changes on gene expression and behavior in this generation is currently unknown, and thus a focus of ongoing studies. Nevertheless, data highlight the possibility that epigenetic changes contribute to the cycle of maltreatment through generations as well as the perpetuation of nurturing behavior that has been previously proposed.

One striking finding from our studies was the inability of cross-fostering to completely rescue CNS DNA methylation changes that a pup acquired as a result of being born to a mother that had herself experienced neonatal maltreatment. If the changes in DNA methylation were entirely attributable to postnatal treatment and experience, one would expect cross-fostering to a normal mother to completely rescue the altered methylation, which it did not. This finding suggests that certain epigenetic marks, or at minimum a predisposition to form these marks, might be inherited through mechanisms involving the prenatal milieu. The importance of the quality of the prenatal environment is underscored by several studies. For example, human infants of mothers with high levels of depression and anxiety during the third trimester have increased methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter in cord blood cells (73). Exposure to cocaine during the second and third trimesters of gestation is sufficient to induce global changes in DNA methylation in the infant hippocampus as well as changes that later emerge in the adolescent (74), and prenatal stress is sufficient to alter site-specific methylation of stress-related genes in the adult hypothalamus and amygdala (75). Still it remains to be determined what types of cells are responsible for the observed DNA methylation changes in these studies as well as in our own study.

As epigenetic mechanisms continue to be linked with neuronal plasticity and psychiatric illnesses, manipulating chromatin structure continues to gain support as a viable avenue for therapeutic intervention to restore cognitive and emotional health. This raises the intriguing speculation that such interventions, such as early exposure to complex environments (enrichment), handling, or treatment with DNA demethylases or histone deacetylase inhibitors, might prove useful as therapeutic strategies for reversing persisting effects of early-life adversity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Li, T.O. Tollefsbol, M. Han, and the UAB Genomics Core Facility for their assistance in bisulfite sequencing. We thank Drs. B.R. Korf, E. Klann, J.H. Meador-Woodruff, and R.M. Sullivan for their comments and critical reading of this manuscript; and F. Hester, E. Ellis, J. Glover, and J. Tate for their technical assistance. This work was funded by grants MH57014, NARSAD, NS048811, and the Evelyn McKnight Brain Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bellis MD. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:150–172. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee V, Hoaken PN. Cognition, emotion, and neurobiological development: mediating the relation between maltreatment and aggression. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:281–298. doi: 10.1177/1077559507303778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaffman A, Meaney MJ. Neurodevelopmental sequelae of postnatal maternal care in rodents: clinical and research implications of molecular insights. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:224–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fumagalli F, Molteni R, Racagni G, Riva MA. Stress during development: impact on neuroplasticity and relevance to psychopathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:197–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noble KG, Tottenham N, Casey BJ. Neuroscience perspectives on disparities in school readiness and cognitive achievement. Future Child. 2005;15:71–89. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP, Kim DM. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bock J, Gruss M, Becker S, Braun K. Experience-induced changes of dendritic spine densities in the prefrontal and sensory cortex: correlation with developmental time windows. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:802–808. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branchi I. The mouse communal nest: Investigating the epigenetic influences of the early social environment on brain and behavior development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.011. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branchi I, Francia N, Alleva E. Epigenetic control of neurobehavioural plasticity: the role of neurotrophins. Behav Pharmacol. 2004;15:353–362. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200409000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenoglio KA, Brunson KL, Baram TZ. Hippocampal neuroplasticity induced by early-life stress: functional and molecular aspects. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graff J, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic codes in cognition and behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda TB, Jones PA. DNA methylation: the nuts and bolts of repression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:384–390. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown SE, Weaver ICG, Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Regional-specific global cytosine methylation and DNA methyltransferase expression in the adult rat hippocampus. Neurosci Letters. 2008;440:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kangaspeska S, Stride B, Metivier R, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Ibberson D, Carmouche RP, et al. Transient cyclical methylation of promoter DNA. Nature. 2008;452:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Peron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, et al. Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegmund KD, Connor CM. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex Is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey CH, Kandel ER, Si K. The persistence of long-term memory: a molecular approach to self-sustaining changes in learning-induced synaptic growth. Neuron. 2004;44:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M. Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn Memory. 2007;14:268–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.500907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Wang X, Dobbin M, Tsai L-H. Recovery of learning and memory is associated with chromatin remodeling. Nature. 2007;447:178–182. doi: 10.1038/nature05772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korzus E, Rosenfeld MG, Mayford M. CBP histone acetyltransferase activity is a critical component on memory consolidation. Neuron. 2004;42:961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubin FD, Roth TL, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic regulation of bdnf gene transcription in the consolidation of fear memory. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10576–10586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1786-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller CA, Sweatt JD. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron. 2007;53:857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. Activity-dependent suppression of miniature neurotransmission through the regulation of DNA methylation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:395–406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3796-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang AC, Zou B, Reeb BC, Connor JA. An epigenetic induction of a right-shift in hippocampal asymmetry: selectivity for short- and long-term potentiation but not post-tetanic potentiation. Hippocampus. 2008;18:5–10. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsankova N, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve R, Nestler E. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nature Neurosci. 2006;9:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nn1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Human Gen. 2008;82:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsankova N, Renthal W, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:355–367. doi: 10.1038/nrn2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa E, Chen Y, Davis J, Dong E, Noh JS, Tremolizzo L. REELIN and schizophrenia: a disease at the interface of the genome and the epigenome. Mol Intervent. 2002;2:47–57. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guidotti A, Ruzicka W, Grayson DR, Veldic M, Pinna G, Davis JM, Costa E. S-adenosyl methionine and DNA methyltransferase-1 mRNA overexpression in psychosis. Neuroreport. 2007;18:57–60. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32800fefd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGowan PO, Sasaki A, Huang TCT, Unterberger A, Suderman M, Ernst C, et al. Promoter-wide hypermethylation of the ribosomal RNA gene promoter in the suicide brain. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivy AS, Brunson KL, Sandman C, Baram TZ. Dysfunctional nurturing behavior in rat dams with limited access to nesting material: A clinically relevant model for early-life stress. Neurosci. 2008;154:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth TL, Sullivan RM. Memory of early maltreatment: neonatal behavioral and neural correlates of maternal maltreatment within the context of classical conditioning. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak K, Schmittgen T. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfaffl M. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippmann M, Bress A, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM, Monteggia LM. Long-term behavioural and molecular alterations associated with maternal separation in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3091–3098. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nair A, Vadodaria KC, Banerjee SB, Benekareddy M, Dias BG, Duman RS, Vaidya VA. Stressor-specific regulation of distinct brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein expression in the postnatal and adult rat hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;32:1504–1519. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shelton RC. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Psychiat Clin N Am. 2007;30:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Lipska BK, Herman MM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor in prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:592–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Q-R, Lu L, Zhu X-G, Gong J-P, Shaham Y, Uhl GR. Rodent BDNF genes, novel promoters, novel splice variants, and regulation by cocaine. Brain Res. 2006;1067:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sathanoori M, Dias BG, Nair AR, Banerjee SB, Tole S, Vaidya VA. Differential regulation of multiple brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts in the postnatal and adult rat hippocampus during development, and in response to kainate administration. Molecular Brain Research. 2004;130:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y, et al. DNA Methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent bdnf gene regulation. Science. 2003;302:890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.1090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dennis KE, Levitt P. Regional expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is correlated with dynamic patterns of promoter methylation in the developing mouse forebrain. Mol Brain Res. 2005;140:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maisonpierre PC, Belluscio L, Friedman B, Alderson RF, Wiegand SJ, Furth ME, et al. NT-3, BDNF, and NGF in the developing rat nervous system: Parallel as well as reciprocal patterns of expression. Neuron. 1990;5:501–509. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herz J, Chen Y. Reelin, lipoprotein receptors and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:850–859. doi: 10.1038/nrn2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver I, Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Maternal care effects on the hippocampal transcriptome and anxiety-mediated behaviors in the offspring that are reversible in adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3480–3485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng JC, Matsen CB, Gonzales FA, Ye W, Greer S, Marquez VE, et al. Inhibition of DNA methylation and reactivation of silenced genes by zebularine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:399–409. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barreto G, Schafer A, Marhold J, Stach D, Swaminathan SK, Handa V, et al. Gadd45a promotes epigenetic gene activation by repair-mediated DNA demethylation. Nature. 2007;445:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature05515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Detich N, Bovenzi, Szyf M. Valproate induces replication-independent active DNA demethylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27586–27592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kress C, Thomassin H, Grange T. Active cytosine demethylation triggered by a nuclear receptor involves DNA strand breaks. PNAS. 2006;103:11112–11117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601793103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Champagne FA. Epigenetic mechanisms and the transgenerational effects of maternal care. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleming AS, Kraemer GW, Gonzalez A, Lovic V, Rees S, Melo A. Mothering begets mothering: the transmission of behavior and its neurobiology across generations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:61–75. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lovic V, Gonzalez A, Fleming AS. Maternally separated rats show deficits in maternal care in adulthood. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;39:19–33. doi: 10.1002/dev.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maestripieri D, Lindell SG, Higley JD. Intergenerational transmission of maternal behavior in rhesus macaques and its underlying mechanisms. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:165–171. doi: 10.1002/dev.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanchez MM. The impact of early adverse care on HPA axis development: nonhuman primate models. Horm Behav. 2006;50:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Febo M, Numan M, Ferris CF. Functional magnetic resonance imaging shows oxytocin activates brain regions associated with mother-pup bonding during suckling. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11637–11644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3604-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hernandez-Gonzalez M, Navarro-Meza M, Prieto-Beracoechea CA, Guevara MA. Electrical activity of prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area during rat maternal behavior. Behav Proc. 2005;70:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Numan M. Motivational systems and the neural circuitry of maternal behavior in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:12–21. doi: 10.1002/dev.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:571–585. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moles A, Rizzi R, D’Amota FR. Postnatal stress in mice: does “stressing” the mother have the same effect as “stressing” the pups? Dev Psychobiol. 2004;44:230–237. doi: 10.1002/dev.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Champagne F, Weaver I, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinol. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Champagne FA, Curley JP. Epigenetic mechanisms mediating the long-term effects of maternal care on development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.009. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McLeod J, Sinal CJ, Perrot-Sinal TS. Evidence for non-genomic transmission of ecological information via maternal behavior in female rats. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richards EJ. Inherited epigenetic variation - revisiting soft inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:395–401. doi: 10.1038/nrg1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szyf M, Weaver I, Meaney M. Maternal care, the epigenome and phenotypic differences in behavior. Reproductive Toxicol. 2007;24:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Novikova SI, He F, Bai J, Cutrufello NJ, Lidow MS, Undieh AS. Maternal cocaine administration in mice alters DNA methylation and gene expression in hippocampal neurons of neonatal and prepubertal offspring. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mueller BR, Bale TL. Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9055–9065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1424-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.