Abstract

Using data from 34 participants who completed an emotion-word Stroop task during functional magnetic resonance imaging, we examined the effects of adult attachment on neural activity associated with top-down cognitive control in the presence of emotional distractors. Individuals with lower levels of secure-base-script knowledge—reflected in an adult’s inability to generate narratives in which attachment-related threats are recognized, competent help is provided, and the problem is resolved—demonstrated more activity in prefrontal cortical regions associated with emotion regulation (e.g., right orbitofrontal cortex) and with top-down cognitive control (left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and superior frontal gyrus). Less efficient performance and related increases in brain activity suggest that insecure attachment involves a vulnerability to distraction by attachment-relevant emotional information and that greater cognitive control is required to attend to task-relevant, nonemotional information. These results contribute to the understanding of mechanisms through which attachment-related experiences may influence developmental adaptation.

Keywords: attachment, secure-base-script knowledge, cognitive control, emotion regulation, Stroop, fMRI

Despite theoretical claims and considerable evidence that individual differences in attachment security provide a foundation for social and emotional development (Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005), surprisingly few studies have investigated specific neural mechanisms linking attachment-related variation to socioemotional adaptation and maladaptation. Most of the literature integrating attachment and neuroscience is theoretical rather than empirical, and studies of the neural circuitry associated with attachment are quite rare (Coan, 2008). The present study addressed this need by examining individual differences in neural responses to emotional stimuli as a function of adult attachment.

Attachment Theory, Emotional Organization, and Cognitive Representation

Bowlby (1979) highlighted the role of emotion in the development of attachment relationships and suggested that distinctive patterns of emotional response, self-regulation, and cognitive evaluation emerge from attachment histories (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). For example, secure adults are thought to have a preponderance of positive affect, enduring emotional security, and flexible expressions of emotion, all of which increase the effectiveness of adaptation. Insecure adults are thought to suppress negative affect or to have dysregulated emotional responses, both of which result in vulnerability to interpersonal maladaptation (Cassidy & Kobak, 1988). The neural processes associated with these patterns have rarely been measured (though see Dozier & Kobak, 1992; Groh & Roisman, 2009; Roisman, 2007; Roisman, Tsai, & Chiang, 2004). Investigating these neural associations may advance understanding of how attachment is linked to overt behavior and of attachment-related mechanisms that have historically been inferred.

Adult Attachment and Neural Mechanisms of Cognition and Emotion

Narrative-based measures of adult attachment such as the Attachment Script Assessment (ASA; Waters & Rodrigues-Doolabh, 2004) and the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; Main et al., 1985) are widely used in developmental psychology. The ASA is used to analyze stories generated in response to attachment-related word prompts, and the AAI is used to assess accounts of autobiographical experiences. Secure-base-script knowledge, as assessed by the ASA, is an index of the degree to which an individual is able to generate narratives in which attachment-related threats are recognized, competent help is provided, and the problem is resolved in a hypothetical situation.

Using the AAI, a measure of the coherence of adults’ narratives about their childhood experiences, Dozier and Kobak (1992) and Roisman et al. (2004) found that insecure, dismissing adults (who idealized their caregivers or normalized harsh childhood experiences) showed elevated electrodermal activity during the interview, which suggests that these individuals were suppressing or deactivating emotion systems. Roisman and his colleagues have extended this line of research, finding (a) that insecure adults show relatively high levels of electrodermal reactivity when discussing areas of disagreement with their romantic partners (Roisman, 2007) and (b) that individuals with low levels of secure-base-script knowledge also demonstrate heightened skin conductance in response to attachment-related distress vocalizations (a baby crying; Groh & Roisman, 2009).

Only one study to date has used central nervous system measures to examine neural correlates of access to a secure base script. Buchheim et al. (2006) used the Adult Attachment Projective and had participants vocalize attachment-relevant stories during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, methodological issues in this study (e.g., potentially significant movement artifact due to vocalization, lack of correction for multiple comparisons, and relatively small sample size) preclude firm conclusions.

Two other fMRI studies focused on self-reported attachment style. In the first study (Gillath, Bunge, Shaver, Wendelken, & Mikulincer, 2005), participants were asked to think about negative relationship scenarios. Adults who reported high levels of attachment-related anxiety (i.e., those who worried about the availability and responsiveness of relationship partners) showed increased activity in brain areas associated with negative emotion (e.g., right posterior cortex; see Heller, Koven, & Miller, 2003, for a review). These adults also showed less activity in brain regions associated with the down-regulation of negative emotions than did adults who reported low levels of attachment-related anxiety. Attachment-related anxiety was positively associated with activity in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), and this association may reflect a need for increased cognitive control. Consistent with other evidence that insecure attachment may be associated with more effortful processing in suppression of negative affect, the results of Gillath et al. (2005) showed that highly avoidant individuals (those reporting discomfort about relying on other people for attachment-related functions) were less likely to deactivate brain areas directly related to thought suppression than were less avoidant participants.

The second fMRI study that examined self-reported attachment style (Coan, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2006) found that under threat of mild electric shock, self-reported attachment security was associated with less activity in rostral-ventral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) while participants were holding their spouse’s hand and was positively correlated with rACC activity while they were holding a stranger’s hand (rACC has been associated with modulation of affect-related arousal; e.g., Mohanty et al., 2007). In contrast, attachment-related avoidance was associated with increased activity during spouse hand-holding and decreased activity during stranger hand-holding in right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a region implicated in the regulation of negative affect (see Banich et al., 2009, for a review). These findings are thus consistent with the thesis that insecure attachment involves increased effort to suppress or manage negative affect.

Attachment and Attention-Emotion Interaction

Because attachment theory makes explicit claims about how individual differences in security reflect distinctive organizations of emotional response and regulation (with accompanying cognition and overt behavior), directly relevant neural mechanisms for understanding attachment behavior include those involved in emotion and in the interplay between emotion and cognition. Attention is a particularly relevant phenomenon for which individual differences in attachment security and the processing of emotion can be examined. For example, the distinctive patterns of emotion and cognition that emerge as a function of attachment histories are thought to become automatic and self-confirming over time because they influence the interpretation, processing, and memory of social and emotion-laden information (Bowlby, 1988). In addition, considerable research demonstrates that attention is modulated by emotion (see Compton et al., 2003, for a review). Emotional stimuli are more likely to be automatically, rapidly, and extensively processed than are neutral stimuli (e.g., Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001). If attachment-related experiences are self-confirming over time (Belsky, Spritz, & Crnic, 1996), then selective biases in attention toward certain types of information might be expected (e.g., attachment-threat-related emotion stimuli might capture attention). Furthermore, attentional biases toward particular types of emotional information could disrupt processing of nonemotional information.

A few studies have explored attentional bias in attachment patterns using an emotion-word Stroop task, in which researchers ask the participant to ignore emotion-word meanings and to respond as quickly as possible to the color in which the word is written. Reaction time (RT) during the task is often increased for negative words, and this is taken to indicate that the subject’s attention is captured by the emotional content of the word, despite explicit instructions to ignore it. The effect is enhanced by anxiety but can be demonstrated in nonanxious individuals if the sample size is sufficiently large (for a review, see Koven, Heller, Banich, & Miller, 2003). It is also assumed that, to the degree attention is captured by the word, increased cognitive control is required to carry out the task. The Stroop task is therefore an effective probe of implicit or automatic attention to emotional information.

Focusing on individuals who report high levels of attachment-related avoidance, Edelstein and Gillath (2008) found less interference for attachment-related words (e.g., intimate, loss) than for non-attachment-related words. This effect was attenuated during a concurrent cognitive-load task, which suggests that avoidant individuals attempt to inhibit their attention to such information and that cognitive effort is required to do so. Insecure attachment was associated with less interference for threatening words in another study using an emotion-word Stroop task (van Emmichoven, van IJzendoorn, De Ruiter, & Brosschot, 2003). This study used the AAI to classify secure and insecure attachment styles in nonclinical and anxiety-disorder participants. Attachment insecurity was also associated with poorer recall of threatening words. Taken together, findings from emotional Stroop tasks suggest that attachment security is associated with an effortful (although not necessarily explicit or accessible to conscious awareness) suppression of disturbing information.

The Present Study

The present study brought theory and methodology from cognitive neuroscience research on emotion to bear on cognitive, affective, and neurobiological processes related to attachment. Individual differences in neural responses to an emotion-word Stroop task were assessed as a function of secure-base-script knowledge. Building on previous research (e.g., Groh & Roisman, 2009; Koven et al., 2003; Roisman, 2007; Roisman et al., 2004), we hypothesized that individuals lower in secure-base-script knowledge would experience unpleasant emotional stimuli as more disturbing or dysregulating and would therefore show increased activation in brain regions that regulate emotional experience (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex, OFC; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). It was also expected that lower secure-base-script knowledge would elicit a greater attentional bias to such stimuli, and that this bias would require more cognitive effort and control to suppress. This effect would be instantiated in poorer performance (longer RT and more errors) and increased brain activity in regions associated with cognitive control on this task (e.g., DLPFC; e.g., Banich et al., 2009; Engels et al., 2010).

Method

Participants, measures, and procedure

Thirty-four participants (21 females and 13 males; mean age = 35.71 years, SD = 9.23) were recruited from the local community and from an outpatient mental health clinic via advertisements. All participants were right-handed, native speakers of English with self-reported normal color vision and no reported neurological disorders or impairments. Participants were given a laboratory tour, informed of the procedures of the study, and screened for claustrophobia and other contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging participation. Dimensional measures of anxiety and depression, the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Molina & Borkovec, 1994) and the Anxious Arousal and the Anhedonic Depression scales of the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (Watson et al., 1995), were administered during each participant’s first visit to the laboratory (see Table 1 for scores). In other sessions, participants completed an electroencephalogram (EEG) procedure, a diagnostic interview, and the ASA (Waters & Waters, 2006). An fMRI session included the emotion-word Stroop task. The order of the fMRI and EEG sessions was counterbalanced, as was the order of the emotion-word blocks (see the Supplemental Material available online) within fMRI sessions. Only the data from the Stroop task and the ASA are reported here. Two participants were excluded from the study, as their error rates were greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean.

Table 1.

Self-Reported Psychopathology

| Measure | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSWQ anxious apprehension | 47.97 | 13.27 | 18 | 75 |

| MASQ Anxious Arousal | 22.24 | 4.53 | 17 | 39 |

| MASQ Anhedonic Depression | 14.91 | 4.36 | 10 | 27 |

Note: N = 34. The table reports mean scores on the following measures: Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Molina & Borkovec, 1994), Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ) Anxious Arousal scale (Watson et al., 1995), and MASQ Anhedonic Depression 8-item subscale (Nitschke, Heller, Imig, McDonald, & Miller, 2001; Watson et al., 1995).

ASA task

Participants were given two cards, each displaying a title and a list of 12 words, which they were to use in producing a story (themes were baby’s morning and doctor’s office). They were instructed to read the words to get a sense of the content of the story and to tell the “most detailed story possible.” Their stories were audiotaped. The two standard word-prompt lists involved a parent-child dyad and were intended to prime secure-base-script knowledge by introducing attachment-related threats.

The stories were transcribed verbatim prior to scoring. Two trained coders (K.K.B. and G.I.R.) rated each story for secure-base-script knowledge using the 7-point scale designed by Waters and Rodrigues-Doolabh (2004); higher scores represent more access to secure-base-script knowledge. Withinrater correlations for the two stories were .81 and .80, respectively (ps < .01). Interrater agreement (intraclass correlations) ranged from .90 to .95 across stories and was .94 for the total average across stories and raters (all ps < .01). A composite score reflecting secure-base-script knowledge was derived by averaging the security scores across the two raters and two stories. Security scores in this sample averaged 3.71 (SD = 1.55).

Emotion-word Stroop task

Participants completed an emotion-word Stroop task during fMRI data acquisition (see the Supplemental Material available online). The task consisted of blocks of 64 pleasant or 64 unpleasant emotion words alternating with blocks of 64 neutral emotion words. Each trial consisted of one word written in one of four colors (red, yellow, green, or blue) on a black back-ground, with each color occurring equally often with each word type (pleasant, neutral, unpleasant). Trials were pseudorandomized such that no more than two trials featuring the same color appeared in a row. None of the words was repeated. Participants pressed one of four buttons to indicate the color in which each word appeared on the screen while attempting to ignore the word’s meaning. Because emotional stimuli capture greater attention than color stimuli, rapid and correct performance depends on attention being directed away from word meaning.

Image acquisition

Participants completed 32 practice trials during a low-resolution anatomical scan. Gradient field maps were then collected for correction of geometric distortions in the functional data caused by magnetic field inhomogeneity.

A series of 370 fMRI images (16 images per block of 16 stimuli plus rest and fixation periods) were acquired using a gradient-echo echo-planar pulse sequence (repetition time = 2,000 ms, echo time = 25 ms, flip angle = 80°, field of view = 22 cm) on a Siemens (New York, NY) 3-T Allegra head-only scanner. Thirty-eight contiguous oblique axial slices (slice thickness = 3 mm, in-plane resolution = 3.4375 mm × 3.4375 mm, gap between slices = 0.3 mm) were acquired parallel to the anterior and posterior commissures. After the functional acquisition, a 160-slice magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo structural sequence was acquired (slice thickness = 1 mm, in-plane resolution = 1 mm × 1 mm) for registering each participant’s functional data to Montreal Neurological Institute stereotactic space.

fMRI data reduction and analysis

Image processing and analysis relied primarily on tools from the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library (FSL) analysis package (Version 4.1; Analysis Group, University of Oxford FMRIB Centre, 2008). A few analytic tools were also drawn from the Analysis of Functional Neuroimages (AFNI) package (Cox, 2006). Additional region-of-interest analyses were carried out using locally written MATLAB programs (e.g., Herrington et al., 2005) and SPSS Version 17.0. Methods closely followed those described by Engels et al. (2007), who used a different sample with the same task and stimuli, but were adjusted for the higher-resolution magnetic resonance imaging parameters of the present study (see the Supplemental Material). The contrasts of interest for the present study were activations during unpleasant-word blocks compared with neutral-word blocks, and pleasant-word blocks compared with neutral-word blocks.

In order to explore brain regions uniquely associated with secure-base-script knowledge, we entered each participant’s ASA score and three psychopathology scores (each converted to a z score) as predictors into whole-brain, per-voxel, cross-subject regression analyses in FSL. Psychopathology is associated with patterns of activation in prefrontal cortex in this task (Engels et al., 2007, 2010). However, psychopathology is distinct from attachment security (Guttmann-Steinmetz & Crowell, 2006). Indeed, in the present study, zero-order correlations between each psychopathology score and secure-base-script knowledge did not approach significance (ps = .15–.90). Additionally, in simultaneous multiple regressions, the psychopathology scores as a group did not predict variance in secure-base-script knowledge (p = .52). This lack of relationship indicated that it was appropriate (Miller & Chapman, 2001) for the three psychopathology scores to serve as covariates in the main regressions, with secure-base-script knowledge predicting brain activity, in order to reduce noise in the dependent variables. Accordingly, variance shared between these three covariates and either secure-base-script knowledge or brain activity was removed.

Behavioral data

Average RT for correct-response trials was computed for each condition (unpleasant words, neutral words, pleasant words). Unpleasant-word-trial and pleasant-word-trial RT interference scores were computed by subtracting each participant’s average neutral-word RT from his or her average unpleasant-word and pleasant-word RTs, respectively. No-response trials were excluded from behavioral analyses. Errors of commission were tallied for each condition. Error interference scores were calculated by subtracting the number of neutral-word errors from the number of errors in each emotion-word condition, divided by their sums (e.g., [unpleasant-word errors minus neutral-word errors]/[unpleasant-word errors plus neutralword errors]). RT and error interference scores were correlated with ASA to examine the relationship between secure-base-script knowledge and behavioral performance.

Results

Behavioral data

All participants demonstrated color-choice accuracy of at least 90%. As a manipulation check, we examined RT interference for emotion-word trials. Participants demonstrated more RT interference for unpleasant-word trials (M = 19.0 ms, SD = 30.7 ms) than for pleasant-word trials (M = 4.8 ms, SD = 31.4 ms), t(33) = 2.20, p = .04. No error interference difference emerged for pleasant-word trials compared with unpleasant-word trials.

Lower levels of secure-base-script knowledge were generally associated with poorer performance. Secure-base-script knowledge predicted unpleasant-word error interference, r(29) = −.38, p = .02, and pleasant-word error interference, r(29) = −.39, p = .02. In line with our a priori hypothesis, secure-base-script knowledge marginally predicted pleasant-word RT interference, r(29) = −.28, p = .06, but not unpleasant-word RT interference, r(29) = .12, p = .26. Given these two-tailed tests of a one-tailed hypothesis, low levels of secure-base-script knowledge were associated with more errors and slower responses for pleasant words, and more errors for unpleasant words, than were high levels of secure-base-script knowledge.

fMRI data

Unpleasant-word compared with neutral-word contrast

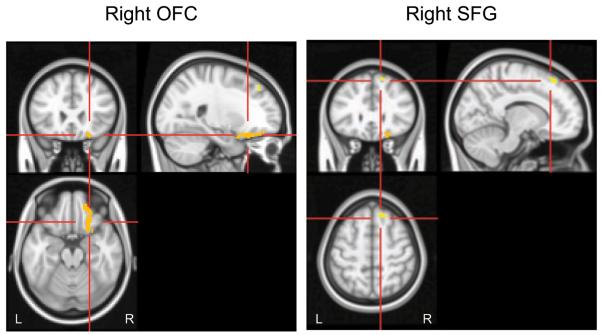

Table 2 lists the two right-hemisphere regions for which the ASA predicted activation during exposure to unpleasant words relative to exposure to neutral words. Figure 1 shows that low secure-base-script knowledge was associated with unpleasant-word activation in OFC and superior frontal gyrus (SFG; extending into DLPFC). Activation in these regions did not correlate with RT or error interference.

Table 2.

Distinct Effects of Secure-Base-Script Knowledge

| COM location |

Maximum-z location |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast and region | Cluster size | Mean z | x | y | z | x | y | z |

| Unpleasant words compared with neutral words | ||||||||

| RH orbitofrontal cortex | 200 | −2.51 | 23 | 29 | −20 | 22 | 26 | −20 |

| RH superior frontal gyrus (extends into DLPFC) | 157 | −2.48 | 19 | 38 | 48 | 14 | 30 | 56 |

| Pleasant words compared with neutral words | ||||||||

| RH precuneus cortex, lingual gyrus | 223 | −2.60 | 16 | −45 | 4 | 26 | −52 | 8 |

| Cingulate gyrus, anterior division (dACC) | 284 | −2.65 | −4 | 29 | 23 | 0 | 28 | 22 |

| LH middle frontal gyrus (DLPFC) | 137 | −2.60 | −24 | 28 | 40 | −26 | 30 | 38 |

| RH precentral gyrus, posterior cingulate | 117 | −2.65 | 6 | −26 | 46 | 6 | −28 | 48 |

| Paracingulate gyrus, superior frontal gyrus | 157 | −2.63 | 0 | 11 | 53 | −6 | 10 | 50 |

Note: N = 34. For unpleasant words compared with neutral words, the table reports regions where z scores were greater than 2.1701 and cluster size was greater than or equal to 156 (corrected p < .05). For pleasant words compared with neutral words, the table reports regions where z scores were greater than 2.3263 and cluster size was greater than or equal to 112 (corrected p < .05). COM = center of mass; dACC = dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; LH = left hemisphere; RH = right hemisphere.

Fig. 1.

Brain regions in which Attachment Script Assessment score predicted unique variance in the contrast of unpleasant-word versus neutral-word activations. The left panel shows activations in right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; x = 22, y = 26, z = −20). The right panel shows activations in right superior frontal gyrus (SFG; x = 14, y = 30, z = 56). Highlighted voxels had z scores greater than 2.1701 and cluster size greater than or equal to 156 (corrected p < .05). L = left; R = right.

Pleasant-word compared with neutral-word contrast

Table 2 lists the regions in which secure-base-script knowledge predicted the difference between pleasant-word and neutral-word activations. Lower levels of secure-base-script knowledge were associated with more brain activation in portions of left DLPFC and dACC (see Fig. 2). Activation in both of these regions also correlated with RT interference on pleasant-word trials, such that the greater the activation in these regions, the greater the observed interference—dACC: r(29) = .40, p = .03; left DLPFC: r(29) = .44, p = .01. Activation in these regions also correlated with error interference on pleasant-word trials, although not significantly—dACC: r(29) = .17, p = .37; left DLPFC: r(29) = .33, p = .07.

Fig. 2.

Brain regions in which Attachment Script Assessment score predicted unique variance in the contrast of pleasant-word versus neutral-word activations and the relationship between reaction time (RT) interference scores and activity in those regions. The upper left panel shows activations in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC; x = 0, y = 28, z = 22). The upper right panel shows activations in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; x = −26, y = 30, z = 38). Highlighted voxels had z scores greater than 2.3263 and cluster size greater than or equal to 112 (corrected p < .05). The lower panels show scatter plots (with best-fitting regression lines) illustrating RT interference on pleasant-word trials as a function of dACC and DLPFC activation residualized for three psychopathology scales. RT interference was calculated by subtracting RT on neutral-word trials from RT on pleasant-word trials. L = left; R = right.

Discussion

The present study investigated the contribution of secure-base-script knowledge, as measured by the ASA, to behavioral performance and brain activity during a task that requires cognitive control to ignore emotional distractors. Consistent with hypotheses that lower secure-base-script knowledge might involve more intense or dysregulated reactions to meanings of negative emotional words, indicators of performance suggested some interference with efficient performance on unpleasant-word trials on the cognitive task. Furthermore, brain regions that have been implicated in efforts to regulate emotion, such as lateral and medial OFC, showed increased activity for unpleasant words (e.g., Elliott, Dolan, & Frith, 2000). In addition, a region in the right hemisphere that has been implicated in inhibitory functions (SFG; e.g., Nielson, Langenecker, & Garavan, 2002) showed more activity in conjunction with lower secure-script knowledge; this finding suggests a mechanism for increased cognitive control in response to negative emotional information. Activation in the right-hemisphere SFG and DLPFC region and in OFC has been observed in various paradigms that require active maintenance in the presence of distracting information (D’Esposito et al., 1995), inhibition (Nielson et al., 2002), and emotion regulation, including instructed inhibition or suppression of negative emotions (Depue, Curran, & Banich, 2007). The present finding of more right-hemisphere activity in these regions for unpleasant words than for neutral words is consistent with predictions that emotion regulation and cognitive control would be required to counteract increased reactivity to emotional information in insecure individuals.

Also consistent with predictions that emotional distractors would require more effort to ignore, findings showed that lower secure-base-script knowledge was associated with enhancement of left-frontal activity and dACC, but only during pleasant-word blocks. Left DLPFC and dACC have been repeatedly implicated in top-down attentional control for this task (Banich et al., 2009; Compton et al., 2003; Herrington et al., 2005; Mohanty et al., 2007). Together, these findings suggest that lower secure-base-script knowledge requires additional cognitive control to overcome the tendency for pleasant words to capture the individual’s attention.

Why these regions were more active for pleasant words than for unpleasant words cannot be addressed conclusively by the present design, but it is conceivable that the pleasant words in this paradigm (e.g., marriage) represented aspects of intimacy that were actually more attention grabbing for subjects with lower secure-base-script knowledge than were the unpleasant words, which, even if disturbing emotionally, were less associated with attachment-specific issues. Thus, the two types of words elicited very different cognitive processes, instantiated in different brain regions reflecting the different psychological processes they engaged. These findings suggest that there is not a simplistic mapping between valence and attachment-related responses. Rather, the features that tap attachment-related processes depend on the nature of the stimuli and the associative networks they engage.

Another possibility is that different types of cognitive control were elicited as a function of valence. Left DLPFC has been proposed to modulate an emphasis on task instructions to enable enhanced focus on the relevant task dimension, in this case, the color of the word (e.g., Banich et al., 2009). In contrast, right SFG may be involved in inhibiting responses to the irrelevant or distracting task dimension, in this case, word meaning (Cohen et al., 1997). Although it is not possible to tease apart these mechanisms in the present study, the engagement of these regions is consistent with the prediction that the need for cognitive control would be enhanced when individuals with lower secure-base-script knowledge are required to ignore both pleasant and unpleasant information with attachment-relevant content. These data support Bowlby’s (1988) notion that insecure individuals have more difficulty regulating negative emotion than secure individuals do and are also less flexible or comfortable in embracing positive emotion.

Measurement of brain activity provides insight into the mechanisms by which attachment may affect cognitive control. Despite the fact that RT interference for unpleasant stimuli relative to neutral stimuli did not increase as a function of low secure-base-script knowledge, brain regions involved in emotion regulation and cognitive control were nevertheless more active. This suggests that the activation findings reflect compensation and are not merely epiphenomenal to the relationship between attachment and RT. In supplementary analyses of attachment as a predictor of brain activation prompted by unpleasant or pleasant words, all fMRI findings survived after partialing out RT interference variance. (The one marginal exception was that the effect size in left DLPFC for pleasant words declined to requiring a one-tailed test for significance, which is an adequate effect size given strong a priori reasons to expect left DLPFC activity in this task.) That the fMRI activation in cognitive-control regions was dispro-portionate to the behavioral effects suggests compensatory efforts to minimize distraction by emotional content.

Although the evidence suggests that insecure individuals engage in compensatory strategies during emotionally challenging conditions, lower secure-base-script knowledge was nevertheless associated with more errors for both unpleasant and pleasant stimuli, so compensatory efforts were not entirely successful. These findings suggest that as the intensity of emotional distractors increases, low levels of secure-base-script knowledge are associated with a decreasing ability to compensate for and regulate the consequent responses. Compensation can have limits even for generic emotional stimuli. It may be that in situations in which the emotional information is more relevant to the individual (either by design or in ecologically valid situations, such as confrontations with intimate partners), insecure attachment would create even more difficulty in maintaining top-down control of attention.

The results of our study point to an interaction of attachment and emotional challenge, but do not rule out a more general tendency of individuals with insecure attachment to attempt to exert increased cognitive control in nonemotional contexts as well. Supplementary analyses supported some specificity for emotional stimuli, as secure-base-script knowledge did not predict region-of-interest activation (in dACC, DLPFC, OFC, SFG) for a contrast comparing neutral-word trials with fixation (all ps >.4).

The brain regions identified in the present study reflect patterns of emotion-cognition synergy associated with adult attachment-related individual differences. The findings support other evidence suggesting that insecure attachment is associated with emotional responses that require increased cognitive resources to manage and that are likely to confer vulnerability to socioemotional maladaptation, including anxiety and depression. These emotional responses appear to be relatively automatic, as reflected in attentional biases and distinctive patterns of activity in brain regions that typically represent implicit information processing (e.g., OFC). Our results thus contribute to theory and methodology across cognitive neuroscience and attachment paradigms and to the understanding of mechanisms through which attachment-related experiences may influence developmental adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marie Banich, Emily Cahill, Amanda Bull, Laura Crocker, and Tracey Wszalek for their contributions.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (P50 MH079485, R01 MH61358, T32 MH19554) and by the University of Illinois Beckman Institute and Department of Psychology.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information may be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- Analysis Group. University of Oxford Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Centre Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library [Computer software] 2008 Retrieved December 2, 2008, from http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fsl/downloading.html.

- Banich MT, Mackiewicz KL, Depue BE, Whitmer A, Miller GA, Heller W. Cognitive control mechanisms, emotion and memory: A neural perspective with implications for psychopathology. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33:613–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Spritz B, Crnic K. Infant attachment security and affective-cognitive information processing at age 3. Psychological Science. 1996;7:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Tavistock; London, England: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge; London, England: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Buchheim A, Erk S, George C, Kächele H, Ruchsow M, Spitzer M, et al. Measuring attachment representation in an fMRI environment: A pilot study. Psychopathology. 2006;39:144–152. doi: 10.1159/000091800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Kobak R. Avoidance and its relation to other defensive processes. In: Belsky J, Nezorski T, editors. Clinical applications of attachment. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 300–323. [Google Scholar]

- Coan JA. Toward a neuroscience of attachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Coan JA, Schaefer HS, Davidson RJ. Lending a hand: Social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science. 2006;17:1032–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JD, Peristein WM, Braver TS, Nystrom LE, Noll DC, Jonides J, Smith EE. Temporal dynamics of brain activation during a working memory task. Nature. 1997;386:604–607. doi: 10.1038/386604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton RJ, Banich MT, Mohanty A, Milham MP, Herrington J, Miller GA, et al. Paying attention to emotion: An fMRI investigation of cognitive and emotional Stroop tasks. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;3:81–96. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. Analysis of Functional Neuroimages [Computer software] 2006 Retrieved from http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/download/

- Depue BE, Curran T, Banich MT. Prefrontal regions orchestrate suppression of emotional memories via a two-phase process. Science. 2007;317:215–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1139560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Esposito M, Detre JA, Alsop DC, Shin RK, Atlas S, Grossman M. The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature. 1995;378:279–281. doi: 10.1038/378279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Kobak RR. Psychophysiology in attachment interviews: Converging evidence for deactivating strategies. Child Development. 1992;63:1473–1480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein RS, Gillath O. Avoiding interference: Adult attachment and emotional processing biases. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:171–181. doi: 10.1177/0146167207310024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dissociable functions in the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex: Evidence from human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:308–317. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels AS, Heller W, Mohanty A, Herrington JD, Banich MT, Webb AG, Miller GA. Specificity of regional brain activity in anxiety types during emotion processing. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:352–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels AS, Heller W, Spielberg JM, Warren SL, Sutton BP, Banich MT, Miller GA. Co-occurring anxiety influences patterns of brain activity in depression. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10:141–156. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillath O, Bunge S, Shaver PR, Wendelken C, Mikulincer M. Attachment-style differences in the ability to suppress negative thoughts: Exploring the neural correlates. NeuroImage. 2005;28:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh AS, Roisman GI. Adults’ autonomic and subjective responses to infant vocalizations: The role of secure base script knowledge. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:889–893. doi: 10.1037/a0014943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Steinmetz S, Crowell JA. Attachment and externalizing disorders: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:440–451. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000196422.42599.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller W, Koven NS, Miller GA. Regional brain activity in anxiety and depression, cognition/emotion interaction, and emotion regulation. In: Hugdahl K, Davidson RJ, editors. The asymmetrical brain. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. pp. 533–564. [Google Scholar]

- Herrington JD, Mohanty A, Koven NS, Fisher JE, Stewart JL, Banich MT, et al. Emotion-modulated performance and activity in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Emotion. 2005;5:200–207. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koven N, Heller W, Banich MT, Miller GA. Relationships of distinct affective dimensions to performance on an emotional Stroop task. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty A, Engels AS, Herrington JD, Heller W, Ho RM, Banich MT, et al. Differential engagement of anterior cingulate cortex subdivisions for cognitive and emotional function. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:343–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina S, Borkovec TD. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associated characteristics. In: Davey GCL, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: Perspectives on theory, assessment and treatment. Wiley; Chichester, England: 1994. pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Nielson KA, Langenecker SA, Garavan H. Differences in the functional neuroanatomy of inhibitory control across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:56–71. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB, Heller W, Imig JC, McDonald RP, Miller GA. Distinguishing dimensions of anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Flykt A, Esteves F. Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:466–478. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI. The psychophysiology of adult attachment relationships: Autonomic reactivity in marital and premarital interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:39–53. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Tsai JL, Chiang K-HS. The emotional integration of childhood experience: Physiological, facial expressiveness, and self-reported emotional response during the Adult Attachment Interview. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:776–789. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E, Collins A. The development of the person: The Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaptation from birth to adulthood. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- van Emmichoven IA, van IJzendoorn MH, De Ruiter C, Brosschot JF. Selective processing of threatening information: Effects of attachment representation and anxiety disorder on attention and memory. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:219–237. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS, Rodrigues-Doolabh L. Manual for decoding secure base narratives. State University of New York at Stony Brook; 2004. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS, Waters E. The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment & Human Development. 2006;8:185–197. doi: 10.1080/14616730600856016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:15–25. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.