Abstract

Maintenance of appropriate cell adhesion is crucial for normal cellular and organismal homeostasis. Certain microRNAs have recently been found capable of regulating molecules that oversee the fundamental cell biological events that drive cellular adhesion. It is now apparent that microRNAs play crucial roles in the great majority of biochemical pathways that contribute to normal cell adhesion. In this Commentary, we describe the latest advances within this still-emerging field, and highlight connections between the deregulation of microRNAs that affect cell-adhesion-associated molecules and the pathogenesis of several human diseases. Current evidence suggests that the ability of certain microRNAs – notably miR-17, miR-29, miR-31, miR-124 and miR-200 – to pleiotropically regulate multiple molecular components of the cell adhesion machinery endows these microRNAs with the capacity to function as key modulators of adhesion-associated processes. This, in turn, holds important implications for our understanding of both the basic biology of cell adhesion and the etiology of multiple pathological conditions.

Key words: Cancer, Cell Adhesion, Integrin, MicroRNA, miR-200, miR-31

Introduction

Cell adhesion status, involving both cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, is a fundamental determinant of a wide variety of cell biological responses (Parsons et al., 2010). For example, in the absence of proper integrin-mediated adhesion to defined components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), many cell types will undergo a form of apoptotic cell death termed anoikis. Similarly, the forced downregulation of cell adhesion molecules is known to adversely affect the survival and proliferation of multiple cell types (Guo and Giancotti, 2004). Thus, cellular adhesion plays a key role in dictating the fate of a cell, in significant part through modulation of the intracellular signal transduction networks that lie downstream of these cell adhesion molecules. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that the deregulation of various cell adhesion molecules has been observed to play a causative role in the etiology of many human diseases, including the development of cancer (Guo and Giancotti, 2004; Parsons et al., 2010). Accordingly, elucidation of upstream signaling networks that control the expression and/or activity of cell adhesion molecules has become a field of intensive research.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute a class of regulatory molecules that have attracted a great deal of attention because of their capacity to modulate the expression levels of cell adhesion proteins. This evolutionarily conserved family of small regulatory RNAs can pleiotropically suppress gene expression through several distinct post-transcriptional mechanisms that depend on sequence-specific interactions of individual miRNAs with the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of their mRNA targets. More than 650 miRNAs have been reported in human cells (Filipowicz et al., 2008; Bartel, 2009). In light of the fact that an individual miRNA can simultaneously modulate the expression levels of dozens – and in some cases even hundreds – of different mRNA targets, it has been estimated that more than half of the total mRNA species encoded in the human genome are likely to be subject to miRNA-mediated control (Friedman et al., 2009).

Given the multitude of mRNA species that are regulated by miRNAs, one might anticipate that aberrant miRNA activity would result in significant cell biological consequences, including those associated with various types of disease states. Indeed, genetic ablation of core components of the miRNA biogenesis machinery is incompatible with cell and/or organismal viability in certain model systems, including cultured mammalian cells and genetically engineered mice (Bernstein et al., 2003; Ambros, 2004). Moreover, altered miRNA expression profiles have been documented to contribute to the pathogenesis of a number of human diseases, such as cardiac abnormalities and cancer development (Ambros, 2004; Ventura and Jacks, 2009; Valastyan and Weinberg, 2009). Hence, maintenance of appropriate miRNA activity is essential for accurate cell and organismal homeostasis, as altered miRNA function leads to widespread deregulation of the myriad complex signaling networks that lie downstream of these miRNAs.

In this Commentary, we will summarize our current knowledge regarding the roles of miRNAs in regulating one specific category of such downstream target genes – cell adhesion molecules. Emerging evidence suggests that miRNAs are capable of controlling the expression levels of many crucial cell adhesion molecules and it is rapidly becoming apparent that miRNAs play imperative key roles in organizing diverse aspects of the biochemical pathways that govern normal cellular adhesion. Additionally, deregulation of some of these miRNAs has been found to contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple human diseases, including neoplastic development and subsequent metastatic progression. When taken together, these findings carry significant implications for our understanding of cell adhesion. In addition, in cases of diseases caused in part by deregulated cell adhesion, this research suggests that certain miRNAs represent attractive molecular targets for the development of novel therapeutic agents.

MicroRNA-mediated suppression of cell adhesion molecules

Cell adhesion physically couples the actin cytoskeleton of a cell either to the actin cytoskeleton of a neighboring cell or to defined components of the surrounding ECM. Thus, cell adhesion arises through the concerted actions of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, cell–cell adhesion molecules, cell–matrix adhesion molecules and ECM proteins (Parsons et al., 2010). Interestingly, research conducted over the past five years has revealed that certain miRNAs are capable of regulating mRNAs that encode proteins that function in each of these four major categories of adhesion-related processes.

Cytoskeletal regulatory proteins

The actin cytoskeleton is a highly dynamic entity, and even subtle perturbation of the rates of actin polymerization and depolymerization can cause dramatic changes in cellular behavior. In many cases, deregulation of these processes can create pathological conditions. Consequently, cytoskeletal dynamics are tightly controlled under normal physiological settings (Parsons et al., 2010). One central control node that oversees actin polymerization and depolymerization is composed of members of the Rho superfamily of small GTPases, which encompasses the Rho, Rac and Cdc42 subfamilies (Heasman and Ridley, 2008).

Certain miRNAs have been found to target mRNAs encoding members of the Rho superfamily. For example, miR-31 (Valastyan et al., 2009a; Valastyan et al., 2009b), miR-133 (Cáre et al., 2007) and miR-155 (Kong et al., 2008) suppress the expression levels of RhoA in various different tissue types. Similarly, RhoC is a direct downstream effector of miR-138 (Jiang et al., 2010), as well as an indirect downstream target of miR-10b (Ma et al., 2007). Expression of the small GTPase Cdc42 can be suppressed by the miRNAs miR-29 (Park et al., 2009), miR-133 (Cáre et al., 2007) and miR-224 (Zhu et al., 2010). It is therefore interesting to note that miR-133 is capable of simultaneously suppressing the expression levels of two distinct GTPases – namely, RhoA and Cdc42 – that play fundamental roles in controlling cytoskeletal dynamics.

The functional outputs of Rho, Rac and Cdc42 are controlled not only by modulation of the overall expression levels of these proteins, but also through the functional activation of these small GTPases by GTP loading (Heasman and Ridley, 2008). It seems that miRNAs play a crucial role in overseeing these post-translational regulatory events as well. For example, Tiam1, a Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), is a downstream effector of miR-10b (Moriarty et al., 2010). Analogously, miR-151 can target the mRNA encoding RhoGDIA (Ding et al., 2010). Thus, miRNAs can impact small GTPase signal transduction at multiple distinct nodes of intervention.

Additionally, Rho superfamily signaling can be controlled at the level of expression of downstream effectors of the small GTPases (Parsons et al., 2010); once again, miRNAs can participate in this mode of regulation. The Rho effector kinase ROCK2, for example, can be targeted by both miR-138 (Jiang et al., 2010) and miR-139 (Wong et al., 2010). Accordingly, miR-138 can regulate Rho-dependent signaling through suppression of both RhoC itself and the downstream effector kinase ROCK2. This form of regulation, in which an individual miRNA is capable of simultaneously downregulating multiple components of the same signal transduction pathway, is not unprecedented and is believed to represent a means by which pleiotropically acting miRNAs can exert precise control over important signaling networks (Bartel, 2009).

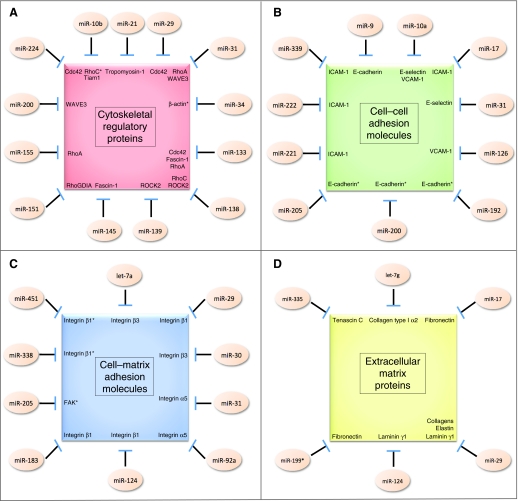

Ultimately, signaling by many Rho GTPase superfamily members funnels through a series of downstream actin-regulating proteins that directly modulate the dynamics of actin polymerization and depolymerization (Heasman and Ridley, 2008). Here too, miRNAs play a crucial role in overseeing cytoskeletal remodeling. For example, miR-31 (Sossey-Alaoui et al., 2010) and the miR-200 family (Sossey-Alaoui et al., 2009) are capable of suppressing levels of the actin polymerization factor WASP-family protein member 3 (WAVE3), whereas miR-21 can control expression of the actin regulatory protein tropomyosin-1 (Zhu et al., 2007). Similarly, expression of the actin-bundling molecule fascin-1 can be suppressed by both miR-133a and miR-145 (Chiyomaru et al., 2010). Moreover, it appears that the miRNA miR-34 can regulate the mRNA encoding β-actin itself, although this modulatory interaction might be quite complex and seems to involve the miRNA-mediated stabilization of an alternatively polyadenylated β-actin mRNA species (Ghosh et al., 2008). When assessed collectively, the above-cited studies clearly indicate that miRNAs play a pervasive role in regulating biochemical pathways relevant to cell adhesion through their capacity to control the expression levels of numerous cytoskeletal regulatory proteins (Fig. 1A) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

MicroRNA-imposed regulation of cell adhesion molecules. Schematic depicting microRNAs (miRNAs) that have been described to modulate the expression levels of (A) cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, (B) cell–cell adhesion molecules, (C) cell–matrix adhesion molecules and (D) extracellular matrix proteins. Asterisks denote indirect downstream targets of the indicated miRNA. ‘Collagens’ refers to the following collagen genes, all of which have been demonstrated to be downstream targets of miR-29: collagen type I α1, collagen type III α1, collagen type IV α1, collagen type IV α2, collagen type V α1, collagen type V α2, collagen type V α3, collagen type VII α1 and collagen type VIII α1.

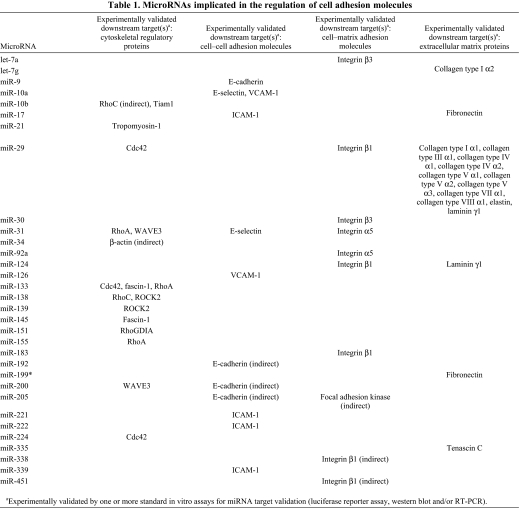

Table 1.

MicroRNAs implicated in the regulation of cell adhesion molecules

Cell–cell adhesion molecules

Maintenance of proper cell–cell adhesion is crucial for a variety of cell types. Cell–cell adhesion plays a vital role in homeostatic control by creating the physical tethering that permits assembly of complex tissues. Furthermore, within individual cells, the activation of various signal transduction pathways is initiated by cell–cell adhesion receptors (Parsons et al., 2010). It is therefore logical that deregulation of cell–cell adhesion interfaces can contribute to the pathogenesis of human diseases. Accordingly, cell–cell adhesion is an intricately regulated process during normal organismal development and physiology (Thiery et al., 2009).

The predominant cell–cell adhesion molecule present on virtually all epithelial cell types is the cadherin family member E-cadherin (Thiery et al., 2009). E-cadherin can be targeted by the miRNA miR-9 (Hao-Xiang et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2010). In addition to direct regulation of the E-cadherin-encoding mRNA, miRNAs play a crucial role in determining ultimate E-cadherin levels through their capacity to modulate expression of the transcription factors zinc finger E-box-binding proteins 1 and 2 (ZEB1 and ZEB2), which can repress transcription from the E-cadherin gene. More specifically, the miR-200 seed family [i.e. those miRNAs sharing the same eight nucleotide sequence at their 5′ ends that is thought to determine their ability to specifically target certain mRNAs (Bartel, 2009)] (Gregory et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008; Korpal et al., 2008) – as well as miR-192 and miR-205 (Wang et al., 2010) – can bind the 3′ UTRs of ZEB1 and ZEB2, thereby mediating their post-transcriptional downregulation; this leads, in turn, to increased E-cadherin expression levels.

It has been discovered that not only can the miR-200 family suppress expression of ZEB1 and ZEB2, but so too can ZEB1 and ZEB2 transcriptionally repress levels of miR-200 family members (Bracken et al., 2008; Thiery et al., 2009). These findings regarding a reciprocal regulatory relationship between the miR-200 family and ZEB1 and ZEB2 are noteworthy, as the status of this double-negative feedback loop has been proposed to represent a crucial governor of the epithelial phenotype in light of experimental evidence indicating that miR-200 expression is largely incompatible with the mesenchymal phenotype (Park et al., 2008; Bracken et al., 2008; Thiery et al., 2009). More generally, the pleiotropic ability of the miR-200 seed family to coordinately target both cytoskeletal regulatory proteins and cell–cell adhesion molecules is potentially highly significant for overall cell adhesion dynamics, as these multiple control nodes probably afford increased potency for exerting phenotypic influences.

In contrast to the E-cadherin-mediated cell–cell adhesion that operates in epithelial tissues, cell–cell adhesion in the bloodstream is often achieved through the actions of members of the selectin family of cell adhesion receptors (Parsons et al., 2010). The selectin family member E-selectin can be suppressed by the miRNAs miR-10a (Fang et al., 2010) and miR-31 (Suárez et al., 2010). Here again, it is interesting that an individual miRNA – in this case, miR-31 – can pleiotropically regulate mRNA targets that are involved in a variety of distinct cellular processes relevant for dictating overall cell adhesion status. Thus, miR-31 can modulate both cytoskeletal regulatory factors and cell–cell adhesion molecules, as well as cell–matrix adhesion receptors, as will be described below.

The immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) represent another important class of cell–cell adhesion receptors (Parsons et al., 2010). Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) is targeted by miR-17 (Suárez et al., 2010), miR-221 (Hu et al., 2010), miR-222 (Ueda et al., 2009) and miR-339 (Ueda et al., 2009). Similarly, miR-10a (Fang et al., 2010) and miR-126 (Harris et al., 2008) can control the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). When taken together, the findings detailed above indicate that miRNAs can regulate the expression levels of mRNAs that encode a variety of different cell–cell adhesion factors, thereby reinforcing the roles of these small RNAs in overseeing pathways central to cellular adhesion dynamics (Fig. 1B) (Table 1).

Cell–matrix adhesion molecules

Within tissues, cells must adhere properly not only to one another, but also to components of the ECM that surrounds them (Parsons et al., 2010). Indeed, appropriate interactions between cells and the surrounding ECM are crucial for normal cellular survival. This explains why cells that participate in disease processes involving detachment from the ECM – for example, tumor cells undergoing metastasis – must become tolerant of reduced cell–matrix interactions (Guo and Giancotti, 2004). Members of the integrin family of cell–matrix adhesion receptors are key regulators of cell–matrix interactions in a wide variety of tissue types (Parsons et al., 2010).

Certain miRNAs have been found to regulate the expression levels of specific integrins. For example, miR-31 (Valastyan et al., 2009a; Valastyan et al., 2009b) and miR-92a (Bonauer et al., 2009) can bind the 3′ UTR of the mRNA encoding integrin α5, thereby mediating its suppression. Furthermore, integrin β3 can be targeted by the let-7a (Müller and Bosserhoff, 2008) and miR-30 (Yu et al., 2010) miRNAs. Also of interest, integrin β1 seems to be targeted by a number of distinct miRNAs; thus, overall integrin β1 expression levels probably reflect the concomitant actions of multiple miRNA species. The miRNAs reported to directly regulate integrin β1 expression include miR-29 (Liu et al., 2010), miR-124 (Cao et al., 2007) and miR-183 (Li, G. et al., 2010). Moreover, miR-338 and miR-451 affect the trafficking and subcellular localization of integrin β1 through mechanisms that remain incompletely understood (Tsuchiya et al., 2009). Hence, the expression levels of a variety of integrins are controlled by the actions of miRNAs.

Importantly, in addition to physically tethering cells to the surrounding ECM, integrins activate certain cytoplasmic signal transduction pathways in response to their successful engagement with the ECM. A prominent component of these integrin-dependent signaling pathways is the downstream effector focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Parsons et al., 2010). No miRNAs have yet been demonstrated to directly suppress the FAK-encoding mRNA. However, miR-205 has been proposed to indirectly affect FAK by negatively regulating its phosphorylation through mechanisms that are, at present, undefined (Li, J. et al., 2010). Of further note, the genomic locus specifying FAK also harbors the hairpin sequence that encodes miR-151 (Ding et al., 2010). This association might indicate that a yet-to-be-described adhesion-pertinent negative-feedback loop operates here. Thus, expression of FAK might be necessarily accompanied by expression of miR-151, a miRNA that has been reported to target the small GTPase regulatory protein RhoGDIA (Ding et al., 2010). The resulting miR-151-mediated suppression of RhoGDIA levels might dampen those signals that initially emanated from increased FAK expression. When taken together, these emerging insights reveal that miRNAs are capable of regulating cell–matrix adhesion molecules through their ability to both directly control integrin expression at the mRNA level and modulate the levels of various downstream effectors of integrin-initiated signal transduction cascades (Fig. 1C) (Table 1).

Extracellular matrix proteins

As indicated above, integrins physically tether cells to the surrounding ECM. Several prominent classes of ECM proteins, which can display altered activity in human pathological states, serve as ligands for the extracellular domains of well-defined integrins and bind them in a highly substrate-specific manner. These ECM proteins include various collagens, laminins and fibronectin (Guo and Giancotti, 2004; Parsons et al., 2010).

Collagens are a principal protein component of most ECMs and represent the dominant ECM constituent of mesenchymal tissue (Guo and Giancotti, 2004). It is therefore potentially significant that the expression levels of numerous different collagens are regulated by miRNAs. For example, collagen type I α2 is a downstream target of let-7g (Ji et al., 2010). Analogously, miR-29 is capable of suppressing expression of collagen type I α1, collagen type III α1, collagen type IV α1, collagen type IV α2, collagen type V α1, collagen type V α2, collagen type V α3, collagen type VII α1 and collagen type VIII α1 (Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). This capacity of miR-29 to simultaneously target many distinct collagen-encoding mRNAs might suggest a crucial role for miR-29 in overseeing collagen-dependent ECM homeostasis in a variety of tissue contexts.

Laminins represent a second class of important protein components of the ECM. Laminins too can participate in integrin engagement, specifically when these proteins help to assemble the specialized ECM that forms the basal lamina or basement membrane. Notably, alteration of the constituents of the basal lamina is a hallmark of several pathological states, including neoplastic progression (Guo and Giancotti, 2004). In addition to their above-detailed capacity to regulate the expression of various collagens, miR-29 is also capable of downregulating levels of laminin γ1 (Sengupta et al., 2008). Laminin γ1 is also a downstream effector of miR-124 (Cao et al., 2007). It is notable that both miR-29 and miR-124 are capable of pleiotropically regulating downstream effector molecules associated with multiple distinct cell biological programs involved in controlling cell adhesion – namely, cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, cell–matrix adhesion molecules and ECM proteins in the case of miR-29, and cell–matrix adhesion molecules and ECM proteins in the case of miR-124.

Although less abundant than collagens, fibronectin is a crucially important protein constituent of the ECM to which integrins can bind (Guo and Giancotti, 2004). Fibronectin expression can be regulated by miR-17 (Shan et al., 2009) and miR-199a* (Lee et al., 2009). Hence, miR-17 is capable of governing cellular events that are important for cell-adhesion-associated signal transduction not only by controlling the expression of cell–cell adhesion molecules, but also through suppressing levels of mRNAs that encode ECM protein components involved in cell adhesion.

In addition to the above-described integrin-engaging ECM molecules, several additional classes of adhesion-pertinent proteins that are present in the ECM are regulated by specific miRNAs. For example, the anti-adhesive molecule tenascin C is a downstream target of miR-335 (Tavazoie et al., 2008). Furthermore, elastin expression can be potently suppressed by overexpression of miR-29 family members (van Rooij et al., 2008). Together, these studies indicate that miRNAs play a prominent role in controlling the expression levels of various mRNAs encoding protein components of the ECM, thereby underscoring the multifaceted roles played by miRNAs in regulating biochemical pathways that are crucial for cell adhesion (Fig. 1D) (Table 1).

When assessed collectively, the findings outlined above unequivocally reveal diverse and important functions for miRNAs in overseeing the homeostatic maintenance of cell-adhesion-relevant signaling pathways in a vast array of different cell types. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly apparent that miRNAs are likely to play a fundamental role in essentially all aspects of cell adhesion signal transduction. This putatively pervasive role of miRNAs in the regulation of cellular adhesion pathways is probably attributable to the capacity of miRNAs to pleiotropically target various integral components of each of the principal classes of molecules that are responsible for driving cellular processes that are relevant to cell adhesion. More specifically, there are numerous examples of miRNAs that suppress the expression of various proteins belonging to each of the four major subclasses of cell adhesion molecules: cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, cell–cell adhesion molecules, cell – matrix adhesion molecules and ECM proteins (Fig. 1) (Table 1).

Relevance of microRNA-mediated regulation of cell adhesion molecules for disease pathogenesis

Given the central role of miRNAs in regulating various cell adhesion molecules, as well as the crucial nature of proper cellular adhesion for the maintenance of normal cell and organismal homeostasis, it is not surprising that the altered activity of some adhesion-associated miRNAs has been found to contribute to the pathogenesis of a number of distinct human diseases. For example, deregulation of either the miR-29 family (van Rooij et al., 2008) or miR-133 family (Caré et al., 2007) contributes to cardiac abnormalities. These effects have been attributed to the capacities of these miRNAs to alter the expression levels of molecules relevant to cellular adhesion properties – namely, Rho GTPases (van Rooij et al., 2008) and elastin (Caré et al., 2007), respectively. At present, it remains unclear whether altered activity of miR-29 and miR-133 leads to defects in other tissue types, or whether the actions of these miRNAs are limited to the control of cardiac tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis.

The activities of many of the above-mentioned adhesion-related miRNAs have been found to be altered during primary tumor development and subsequent metastatic progression. For example, the miR-17~92 cluster is a well-characterized family of known oncogenic miRNAs, whereas the let-7 seed family functions as a classical tumor suppressor gene in many human tumor types (Ventura and Jacks, 2009). Similarly, several additional miRNAs involved in regulating cell adhesion – such as miR-10b, miR-31, miR-200 and miR-335 – have been found to contribute causally to various aspects of metastatic progression in tumor models (Valastyan and Weinberg, 2009). At a molecular level, these miRNAs appear to affect cancer progression by regulating a number of mRNAs that encode proteins with functions in cell-adhesion-related processes, such as RhoC, RhoA, E-cadherin and tenascin C (Valastyan and Weinberg, 2009). In light of the extensively documented roles of cellular adhesion in the control of apoptotic cell death and cell migration, the convergence of these adhesion-associated miRNAs on the single pathological state of cancer is not entirely unexpected.

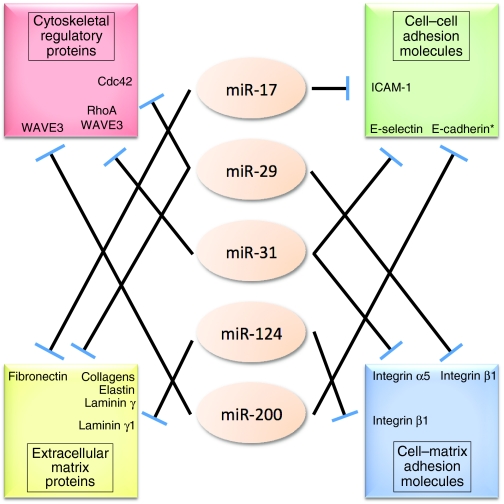

What is quite noteworthy, however, are the observations that those individual miRNAs that are known to target key effectors belonging to more than one of the four major classes of cell adhesion molecules – such as miR-17, miR-29, miR-31 and miR-200 – are the very same miRNAs whose deregulation is closely associated with disease status in various human conditions, as discussed above (Fig. 2) (Table 1) (van Rooij et al., 2008; Ventura and Jacks, 2009; Valastyan and Weinberg, 2009). Such findings provide empirical support for the notion that the profound effects of certain miRNAs on cellular phenotypes derive from the pleiotropic gene regulatory capacity of these miRNAs. Moreover, these associations further underscore the belief that the maintenance of appropriate cell-adhesion-related signal transduction is crucial for normal cellular and organismal homeostasis. Thus, when taken together, the above-cited examples provide evidence that the altered activity of a number of adhesion-pertinent miRNAs contributes crucially to disease pathogenesis.

Fig. 2.

Pleiotropic control of multiple classes of cell adhesion molecules by miR-17, miR-29, miR-31, miR-124 and miR-200. Illustration highlighting the capacity of certain miRNAs to pleiotropically suppress the expression levels of downstream effector molecules belonging to more than one of the four major classes of cell adhesion molecules. Asterisks indicate indirect downstream target of the indicated miRNA. ‘Collagens’ refers to the following collagen genes, all of which have been demonstrated to be downstream targets of miR-29: collagen type I α1, collagen type III α1, collagen type IV α1, collagen type IV α2, collagen type V α1, collagen type V α2, collagen type V α3, collagen type VII α1 and collagen type VIII α1.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The field of miRNA research is still in its infancy. Nonetheless, remarkable progress has already been made in elucidating the functions of these small regulatory RNAs in various cell biological processes. Emerging evidence provides clear indications that miRNAs play crucial roles in numerous aspects of normal cellular homeostasis, including the regulation of cell adhesion molecules. Indeed, many of the key control nodes that operate to dictate cell adhesion decisions are governed by the actions of one or more miRNAs, and future research is likely to uncover additional modulations of cell adhesion molecules imposed by yet other miRNAs.

One striking finding stems from the observation that a subset of miRNAs – which include miR-17, miR-29, miR-31, miR-124 and miR-200 – seems to be particularly well situated within the cellular control circuitry to function as crucial regulators of cell adhesion, owing to their capacity to pleiotropically regulate multiple distinct components of the cell adhesion machinery (Fig. 2) (Table 1). In light of these data, it is tempting to speculate that these particular miRNAs might represent attractive therapeutic targets for the remediation of human diseases characterized by aberrant cell adhesion properties.

At present, it remains unresolved whether additional miRNAs behave analogously to miR-17, miR-29, miR-31, miR-124 and miR-200 in the regulation of cell adhesion molecules. Moreover, it is currently unknown whether miRNAs are capable of directly controlling the expression levels of other molecular factors, such as Rac, components of the Arp2/3 complex, N-cadherin and FAK, which are all known to be important for forming and responding to cell adhesion. Resolution of these issues represents important directions for future research, and is likely to afford crucial insights into the basic biology of cell adhesion and help to identify putative candidates for the treatment of pathological conditions that are mediated by defects in cell adhesion signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Valastyan for assistance in crafting the display items in this manuscript. Research in the authors' laboratories is supported by the NIH, MIT Ludwig Center for Molecular Oncology, US Department of Defense and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. S.V. is a US Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Predoctoral Fellow. R.A.W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and a Daniel K. Ludwig Foundation Cancer Research Professor. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Ambros V. (2004). The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A., Kim S. Y., Carmell M. A., Murchison E. P., Alcorn H., Li M. Z., Mills A. A., Elledge S. J., Anderson K. V., Hannon G. J. (2003). Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat. Genet. 35, 215-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonauer A., Carmona G., Iwasaki M., Mione M., Koyanagi M., Fischer A., Burchfield J., Fox H., Doebele C., Ohtani K., et al. (2009). MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science 324, 1710-1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken C. P., Gregory P. A., Kolensnikoff N., Bert A. G., Wang J., Shannon M. F., Goodall G. J. (2008). A double-negative feedback loop between ZEB1-SIP1 and the microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 68, 7846-7854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Pfaff S. L., Gage F. H. (2007). A functional study of miR-124 in the developing neural tube. Genes Dev. 21, 531-536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caré A., Catalucci D., Felicetti F., Bonci D., Addario A., Gallo P., Bang M. L., Segnalini P., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., et al. (2007). MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 13, 613-618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiyomaru T., Enokida H., Tatarano S., Kawahara K., Uchida Y., Nishiyama K., Fujimura L., Kikkawa N., Seki N., Nakagawa M. (2010). miR-145 and miR-133a function as tumour suppressors and directly regulate FSCN1 expression in bladder cancer. Br. J. Cancer 102, 883-891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Huang S., Wu S., Zhao Y., Liang L., Yan M., Ge C., Yao J., Chen T., Wan D., et al. (2010). Gain of miR-151 on chromosome 8q24.3 facilitates tumour cell migration and spreading through downregulating RhoGDIA. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 390-399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Shi C., Manduchi E., Civelek M., Davies P. F. (2010). MicroRNA-10a regulation of proinflammatory phenotype in athero-susceptible endothelium in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13450-13455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W., Bhattacharyya S. N., Sonenberg N. (2008). Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 102-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R. C., Farh K. K., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 19, 92-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh T., Soni K., Scaria V., Halimani M., Bhattacharjee C., Pillai B. (2008). MicroRNA-mediated up-regulation of an alternatively polyadenylated variant of the mouse cytoplasmic {beta}-actin gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 6318-6332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory P. A., Bert A. G., Paterson E. L., Barry S. C., Tsykin A., Farshid G., Vadas M. A., Khew-Goodall Y., Goodall G. J. (2008). The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 593-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Giancotti F. G. (2004). Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 816-826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao-Xiang T., Qian W., Lian-Zhou C., Zhao-Hui H., Jin-Song C., Xin-Hui F., Liang-Qi C., Xi-Ling C., Wen L., Long-Juan Z. (2010). MicroRNA-9 reduces cell invasion and E-cadherin secretion in SK-Hep-1 cell. Med. Oncol. 27, 654-660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T. A., Yamakuchi M., Ferlito M., Mendell J. T., Lownstein C. J. (2008). MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1516-1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman S. J., Ridley A. J. (2008). Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 690-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G., Gong A. Y., Liu J., Zhou R., Deng C., Chen X. M. (2010). miR-221 suppresses ICAM-1 translation and regulates interferon-gamma-induced ICAM-1 expression in human cholangiocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 298, G542-G550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J., Zhao L., Bundu A., Forques M., Jia H. L., Qin L. X., Ye Q. H., Yu J., Shi X., Tang Z. Y., et al. (2010). Let-7g targets collagen type I alpha2 and inhibits cell migration in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 52, 690-697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Liu X., Kolokythas A., Yu J., Wang A., Heidbreder C. E., Shi F., Zhou X. (2010). Downregulation of the Rho GTPase signaling pathway is involved in the microRNA-138-mediated inhibition of cell migration and invasion in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 127, 505-512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Yang H., He L., Zhao J. J., Coppola D., Dalton W. S., Cheng J. Q. (2008). MicroRNA-155 is regulated by the transforming growth factor beta/smad pathway and contributes to epithelial cell plasticity by targeting RhoA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6773-6784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpal M., Lee E. S., Kang Y. (2008). The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14910-14914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. Y., Shatseva T., Jeyapalan Z., Du W. W., Deng Z., Yang B. B. (2009). A 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) induces organ adhesion by regulating miR-199a* functions. PLoS One 4, e4527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Luna C., Qiu J., Epstein D. L., Gonzalez P. (2010). Targeting of integrin beta1 and kinesin 2alpha by microRNA 183. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5461-5471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Bai H., Zhu Y., Wang X. Y., Wang F., Zhang J. W., Lavker R. M., Yu J. (2010). Antagomir dependent microRNA-205 reduction enhances adhesion ability of human corneal epithelial keratinocytes. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 25, 65-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Hassan M. Q., Jafferji M., Ageilan R. I., Garzon R., Croce C. M., van Wijnen A. J., Stein J. L., Stein G. S., Lian J. B. (2009). Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation of osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15676-15684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Taylor N. E., Lu L., Usa K., Cowley A. W., Jr, Ferreri N. R., Yeo N. C., Liang M. (2010). Renal medullary microRNAs in Dahl salt-sensitive rats: miR-29b regulates several collagens and related genes. Hypertension 55, 974-982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Teruya-Feldstein J., Weinberg R. A. (2007). Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature 449, 682-688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Young J., Prabhala H., Pan E., Mestdagh P., Muth D., Teruya-Feldstein J., Reinhardt F., Onder T. T., Valastyan S., et al. (2010). miR-9, a MYC/MYCN-activated microRNA, regulates E-cadherin and cancer metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 247-256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty C. H., Pursell B., Mercurio A. M. (2010). miR-10b targets Tiam1: implications for Rac activation and carcinoma migration. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20541-20546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D. W., Bosserhoff A. K. (2008). Integrin beta 3 expression is regulated by let-7a miRNA in malignant melanoma. Oncogene 27, 6698-6706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. M., Gaur A. B., Lengyel E., Peter M. E. (2008). The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev. 22, 894-907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Lee J. H., Ha M., Nam J. W., Kim V. N. (2009). miR-29 miRNAs activate p53 by targeting p85 alpha and CDC42. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 23-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R., Schwartz M. A. (2010). Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 633-643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., den Boon J. A., Chen I. H., Newton M. A., Stanhope S. A., Cheng Y. J., Chen C. J., Hildesheim A., Sugden B., Ahlquist P. (2008). MicroRNA 29c is down-regulated in nasopharyngeal carcinomas, up-regulating mRNAs encoding extracellular matrix proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5874-5878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan S. W., Lee D. Y., Deng Z., Shatseva T., Jeyapalan Z., Du W. W., Zhang Y., Zuan J. W., Yee S. P., Siragam V., et al. (2009). MicroRNA MiR-17 retards tissue growth and represses fibronectin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1031-1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossey-Alaoui K., Bialkowska K., Plow E. F. (2009). The miR200 family of microRNAs regulates WAVE3-dependent cancer cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33019-33029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossey-Alaoui K., Downs-Kelly E., Das M., Izem L., Tubbs R., Plow E. F. (2010). WAVE3, an actin remodeling protein, is regulated by the metastasis suppressor microRNA, miR-31, during the invasion-metastasis cascade. Int. J. Cancer doi:10.1002/ijc.25793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Y., Wang C., Manes T. D., Pober J. S. (2010). Cutting edge: TNF-induced microRNAs regulate TNF-induced expression of E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human endothelial cells: feedback control of inflammation. J. Immunol. 184, 21-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie S. F., Alarcón C., Oskarsson T., Padua D., Wang Q., Bos P. D., Gerald W. L., Masagué J. (2008). Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature 451, 147-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. Y., Nieto M. A. (2009). Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139, 871-890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya S., Oku M., Imanaka Y., Kunimoto R., Okuno Y., Terasawa K., Sato F., Tsujimoto G., Shimizu K. (2009). MicroRNA-338-3p and microRNA-451 contribute to the formation of basolateral polarity in epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 3821-3827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda R., Kohanbash G., Sasaki K., Fujita M., Zhu X., Kastenhuber E. R., McDonald H. A., Potter D. M., Hamilton R. L., Lotze M. T., et al. (2009). Dicer-regulated microRNAs 222 and 339 promote resistance of cancer cells to cytotoxic T-lymphocytes by down-regulation of ICAM-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10746-10751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan S., Weinberg R. A. (2009). MicroRNAs: crucial multi-tasking components in the complex circuitry of tumor metastasis. Cell Cycle 8, 3506-3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan S., Benaich N., Chang A., Reinhardt F., Weinberg R. A. (2009a). Concomitant suppression of three target genes can explain the impact of a microRNA on metastasis. Genes Dev. 23, 2592-2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Valastyan S., Reinhardt F., Benaich N., Calogrias D., Szász A. M., Wang Z. C., Brock J. E., Richardson A. L., Weinberg R. A. (2009b). A pleiotropically acting microRNA, miR-31, inhibits breast cancer metastasis. Cell 137, 1032-1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Thatcher J. E., DiMaio J. M., Nasseem R. H., Marshall W. S., Hill J. A., Olson E. N. (2008). Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 13027-13032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A., Jacks T. (2009). MicroRNAs and cancer: short RNAs go a long way. Cell 136, 586-591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Herman-Edelstein M., Koh P., Burns W., Jandeleit-Dahm K., Watson A., Saleem M., Goodall G. J., Twigg S. M., et al. (2010). E-cadherin expression is regulated by miR-192/215 by a mechanism that is independent of the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta. Diabetes 59, 1794-1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. C., Wong C. M., Tung E. K., Au S. L., Lee J. M., Poon R. T., Man K., Ng I. O. (2010). The microRNA miR-139 suppresses metastasis and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by downregulating Rho-kinase 2 (ROCK2). Gastroenterology 140, 322-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Deng H., Yao H., Liu Q., Su F., Song E. (2010). MiR-30 reduction maintains self-renewal and inhibits apoptosis in breast tumor-initiating cells. Oncogene 29, 4194-4204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Si M. L., Wu H., Mo Y. Y. (2007). MicroRNA-21 targets the tumor suppressor gene tropomyosin 1 (TPM1). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14328-14336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Sachdeya M., Wu F., Lu Z., Mo Y. Y. (2010). Ubc9 promotes breast cell invasion and metastasis in a sumoylation-independent manner. Oncogene 29, 1763-1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]