Abstract

NRAS is frequently mutated in hematologic malignancies. We generated Mx1-Cre, Lox-STOP-Lox (LSL)-NrasG12D mice to comprehensively analyze the phenotypic, cellular, and biochemical consequences of endogenous oncogenic Nras expression in hematopoietic cells. Here we show that Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice develop an indolent myeloproliferative disorder but ultimately die of a diverse spectrum of hematologic cancers. Expressing mutant Nras in hematopoietic tissues alters the distribution of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations, and Nras mutant progenitors show distinct responses to cytokine growth factors. Injecting Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice with the MOL4070LTR retrovirus causes acute myeloid leukemia that faithfully recapitulates many aspects of human NRAS-associated leukemias, including cooperation with deregulated Evi1 expression. The disease phenotype in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice is attenuated compared with Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice, which die of aggressive myeloproliferative disorder by 4 months of age. We found that endogenous KrasG12D expression results in markedly elevated Ras protein expression and Ras-GTP levels in Mac1+ cells, whereas Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice show much lower Ras protein and Ras-GTP levels. Together, these studies establish a robust and tractable system for interrogating the differential properties of oncogenic Ras proteins in primary cells, for identifying candidate cooperating genes, and for testing novel therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Ras proteins regulate cell growth by cycling between active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound and inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound states (Ras-GTP and Ras-GDP).1–3 Ras-GTP binds to and activates downstream effectors, such as Raf, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and Ral-GDS. The HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS genes encode 4 highly homologous proteins (H-Ras, K-Ras4A, K-Ras4B, and N-Ras) that share a conserved mechanism of action. The first 85 amino acids are identical and include the effector binding domains and the P loop, which binds the γ-phosphate of GTP. Ras proteins are 85% conserved over the next 80 amino acids, and only diverge substantially over the last 24 amino acids. This “hypervariable region” specifies post-translational modifications that are essential for targeting Ras proteins to cellular membranes.4 Somatic RAS mutations are found in approximately 30% of human cancers and are common in myeloid malignancies.5,6 These alleles encode mutant Ras proteins that accumulate in the GTP-bound conformation because of defective intrinsic GTP hydrolysis and resistance to GTPase activating proteins.1,2,7

Genetic studies imply unique functional properties of different Ras isoforms. Murine Ras genes have distinct roles in development. Whereas homozygous Kras inactivation is lethal during murine embryogenesis, Hras, Nras, and Hras/Nras doubly mutant mice appear normal.3 Potenza et al8 showed that targeting an Hras cDNA to the murine Kras locus rescues the embryonic lethality in Kras mutant animals, suggesting that regulated expression of Ras isoforms modulates developmental programs. In human cancer, KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS are preferentially mutated in distinct tumor types with KRAS mutations highly prevalent in epithelial malignancies. By contrast, NRAS mutations predominate in melanoma and hematopoietic cancers, whereas HRAS mutations are relatively rare.5,6 Understanding the mechanisms that underlie these differences will not only improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis but has implications for developing more selective cancer therapeutics.

Strains of mice in which oncogenic Ras alleles are expressed from the endogenous loci are novel in vivo platforms for investigating the tumorigenic effects of individual isoforms. In the first such model, a “latent” KrasG12D oncogene that is activated by spontaneous recombination induced lung cancer and T lineage leukemia.9 Tissue-specific control of KrasG12D expression from the endogenous locus was subsequently achieved by engineering strains of mice in which a LoxP-STOP-LoxP (LSL) cassette is excised by Cre recombinase.10,11 This general strategy initiated lung and pancreatic cancers and cooperated with Apc inactivation in colon carcinogenesis.10–12 A recent study in which mutant K-Ras and N-Ras proteins with the same glycine-to-aspartate (G12D) oncogenic substitution were expressed at endogenous levels in colonic epithelium extended this paradigm and illustrated that functional differences between Ras isoforms have important effects in tumorigenesis. In this system, KrasG12D, but not NrasG12D, cooperated strongly with loss of Apc in tumorigenesis.12

Somatic NRAS and KRAS mutations occur in diverse myeloid malignancies, including juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML).5,13–16 Overall, NRAS is mutated 2 to 3 times more frequently than KRAS in hematologic cancers.6,16 Clinical and molecular data further suggest that RAS gene mutations initiate or are early events in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and CMML but cooperate with antecedent mutations in AML.17 Consistent with this idea, using Mx1-Cre, which is broadly expressed in hematopoietic cells, to activate the conditional LSL-KrasG12D allele results in an aggressive myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) that closely models juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and CMML.17,18

In this study, we generated Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice and report that endogenous NrasG12D expression perturbs steady-state hematopoiesis, deregulates cytokine responses, and induces a spectrum of fatal hematologic disorders. Injecting Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice with the MOL4070LTR retrovirus results in AML that faithfully recapitulates many aspects of human NRAS-associated leukemias. The in vitro and in vivo effects of oncogenic NrasG12D are distinct from KrasG12D. Interestingly, Kras is expressed at higher levels in myeloid lineage cells, and its expression is further elevated in Kras mutant Mac1+ cells. This increased expression is associated with higher Ras-GTP levels and may partially explain the more aggressive MPD phenotype observed in Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice. Together, these studies establish a robust system for interrogating the distinct biochemical properties of oncogenic Ras proteins in primary cells, for identifying candidate cooperating genes, and for testing novel therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Mouse strains and poly I:C injection

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Committee on Animal Research at the University of California, San Francisco. LSL-NrasG12D mice have been described,12 and heterozygous mutant animals were used in all experiments. Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D and Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of polyriboinosinic acid/polyribocytidylic acid (poly I:C; 250 μg) at 21 days of age (Sigma-Aldrich). Genotyping was performed as described.12,17

Pathologic examination

Mice were observed for signs of disease and were killed when moribund. Cardiac blood was obtained in Microvet EDTA tubes (BD Biosciences) for complete blood cell counts using a Hemavet 850FS (Drew Scientific). Blood smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissue sections of formalin-fixed solid organs were prepared by, and immunohistochemical staining was performed in, the Mouse Pathology Shared Resource at the University of California, San Francisco Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Insertional mutagenesis

Retroviral stocks of MOL4070LTR were generated from a NIH-3T3 producer cell line, and viral titers were assayed as previously described.19 Briefly, pups received a single intraperitoneal injection containing approximately 2 × 106 viral particles between 3 and 5 days of age. Genomic DNA was extracted from the bone marrow and/or spleen of mice that developed AML, and the host-viral junction fragments were cloned and mapped as described.20–22

DNA purification and southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA was purified from hematologic tissues using PUREGENE DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A probe containing MOL4070LTR long-term repeat (LTR) sequences was purified from a sequence-verified vector. Southern analysis was performed as previously described.22

Progenitor colony assays

A total of 5 × 104 nucleated bone marrow cells or 1 × 105 splenocytes were suspended in 1 mL methylcellulose (M3231 for colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage [CFU-GM] and M3234 for burst-forming units-erythroid, Stem Cell Technologies) supplemented with various cytokines. After 8 days of incubation in 35-mm plates at 37°C, 5% CO2, colonies of more than 50 cells were enumerated by direct visualization using indirect microscopy. All assays were performed with at least 3 to 5 mice.

Flow cytometry

Hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors were collected, stained, and analyzed, or isolated as previously described.23 Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) data were acquired with LSRII (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva V6.1.2 software and analyzed with FlowJo Version 8.8.7 software (TreeStar).

Biochemistry

Western blot and flow cytometric analyses to measure the levels of total and phosphorylated proteins in primary hematopoietic cells were performed as previously described.24 Ras-GTP levels were determined as reported previously16 using a fragment of Raf to immunoprecipitate GTP-bound Ras. Anti-K-Ras (F234) and N-Ras (F155) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Proliferation assay

DNA synthesis was assessed by measuring the incorporation of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU), which was administered intraperitoneally (150 mg/kg) 2.5 hours before death. Bone marrow cells and splenocytes were harvested into FACS buffer (Hanks buffer containing 3% fetal bovine serum) on ice. Red blood cells were lysed, and mononucleated cell number was determined in a ViCell instrument (Beckman Coulter). The cells were then stained, fixed, and permeabilized according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were then stained with an anti-BrdU antibody conjugated, and DNA content was measured by 7-amino-actinomycin D. BrdU incorporation was then measured by flow cytometry in an LSRII instrument (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva V6.1.2 and FlowJo Version 8.8.7 software.

RNA purification and quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was purified from bone marrow using the RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN). A total of 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad), and the resulting cDNA was used as template for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The sequence for murine glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to normalize the amount of total cDNA. The premixed probe and primer assay mixtures that were used to quantify Nras, Kras, and GAPDH expression were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Results

MPD in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice

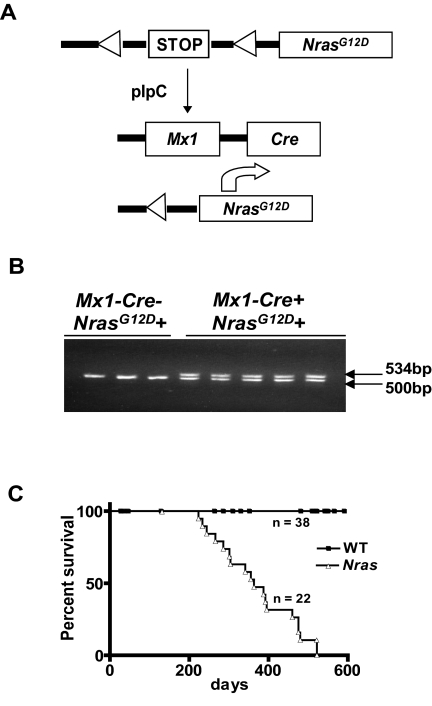

We intercrossed LSL-NrasG12D,12 and Mx1-Cre mice and administered a single dose of poly I:C at weaning to activate the Mx1 promoter (Figure 1A). Excision of the inhibitory LSL cassette was readily detected in blood 3 weeks later (Figure 1B). To quantify the recombination rate in myeloid progenitors, we enumerated CFU-GM colonies in methylcellulose medium containing a saturating concentration of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and picked individual colonies for molecular analysis. These studies revealed activation of the latent NrasG12D allele in approximately 70% of CFU-GM in 6-week-old animals (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Reduced survival of Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice. (A) Injecting Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice with poly I:C excises a transcriptional repressor (“STOP”) cassette and induces NrasG12D expression from the endogenous genetic locus. (B) The recombined NrasG12D allele is detected in blood cells 3 weeks after a single injection of poly I:C (250 μg) in mice that inherited the Mx1-Cre transgene (Mx1−Cre+) but not in Mx1−Cre− littermates. The DNA fragments amplified from the WT and recombined alleles migrate at 500 and 534 bp, respectively. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D (n = 22) and control WT littermates (n = 38) in the C57BL6/129Sv/jae F1 background (P < .0001).

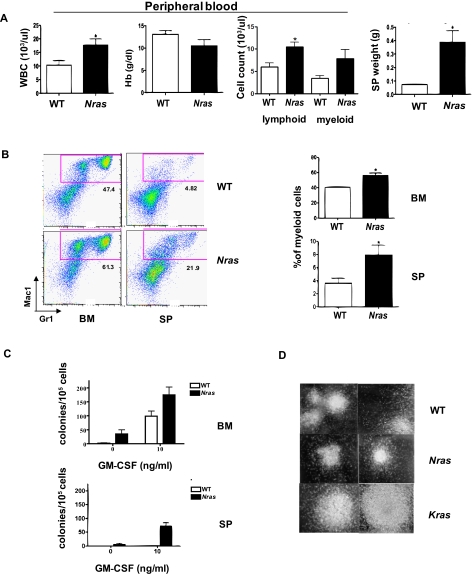

Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice appeared well until after 200 days of age and survived for a median of 363 days on a C57BL6 × 129Sv F1 strain background (Figure 1C). We electively killed mutant and littermate control mice at 6 months of age to analyze the hematopoietic compartment. Nras mutant mice consistently developed MPD with elevated white blood cell counts, splenomegaly, and myeloid infiltration of bone marrow and spleen, which were confirmed by flow cytometric analysis (Figure 2A-B). The splenomegaly and myeloid infiltration can be detected as early as 2 weeks after poly I:C injection, suggesting a direct effect of NrasG12D activation (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Nras mutant bone marrow contained small numbers of cytokine-independent colonies and yielded more CFU-GM colonies than wild-type (WT) marrow when grown in saturating concentration of GM-CSF (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the morphologies of NrasG12D and WT CFU-GM colonies were similar (Figure 2D). By contrast, Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D bone marrow cells form very large monocytic colonies under these conditions (Figure 2D). The spleens of Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice also contained many CFU-GM, including some that showed cytokine-independent growth (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Myeloproliferation in Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice. Hematopoietic tissues from F1 Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice (Nras, n = 14) that appeared well at 6 months of age were analyzed in parallel with specimens from WT littermates (n = 10). (A) Peripheral blood analysis and spleen weight from Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice and WT littermates. P value for the mean white blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentrations (Hb), peripheral lymphocyte and myeloid cell (neutrophils and monocytes) counts, and spleen (SP) weights are .0356, .1825, .0084, .1093, and .0053, respectively. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells (BM) and splenocytes (SP) with the myeloid markers Gr1 and Mac1. The frequency of the cells in the red gate (mac1+Gr1low and Mac1+Gr1+) was used to calculate the percentage of myeloid cells. A summary of 14 Nras mutant and 10 WT animals is shown on the right. P values for bone marrow and spleen are .0015 and .0379, respectively. (C) CFU-GM colonies were enumerated from WT and Nras mutant BM and SP in methylcellulose cultures containing no cytokines or a saturating dose concentration of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL). (D) Morphology of CFU-GM colonies from WT, Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D (Nras), and Mx1-Cre, KrasG12D (Kras) BM (original magnification × 40).

Ineffective erythropoiesis and lymphoproliferation in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice

Hemoglobin levels were consistently reduced in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice by 6 months of age (Figure 2A). Interestingly, however, histopathology revealed an increased number of erythroid precursors in these mice (data not shown). To assess the erythroid progenitor compartment, we compared burst-forming units-erythroid colony growth from the bone marrows and spleens of 3- to 6-month-old WT and Nras mutant littermates in cultures containing a saturating dose of erythropoietin. Under these conditions, Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mutant bone marrow cells and splenocytes formed 2.5 and 10 times more burst-forming units-erythroid colonies than the controls, respectively (supplemental Figure 2A). We also labeled Mac1−/Gr1− bone marrow cells from 3- to 6-month-old mice with antibodies to CD71 and Ter119 and performed flow cytometry.25–27 Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice showed an expanded population of immature CD71high/Ter119lo cells (7.2% ± 3.4% vs 3.7% ± 1.9% in WT mice) and a reciprocal decrease in the more mature CD71high/Ter119high compartment (25.2% ± 1.3% vs 34.6% ± 2.3%, supplemental Figure 2B). Together, these studies demonstrate that endogenous NrasG12D expression results in ineffective erythropoiesis because of a cell intrinsic defect at the proerythroblast stage of differentiation.

In addition to myeloid hyperplasia and a mild defect in erythroid maturation, all Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice had lymphoproliferation by 6 months of age. This was characterized by increased peripheral blood lymphocyte counts, expansion of the splenic white pulp, and perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes within the liver and lungs (Figure 2A, supplemental Figures 3, 4C; and data not shown). Enlarged lymph nodes or extranodal lymphoid hyperplasia was also seen in some mice (supplemental Figure 4C; and data not shown). Immunohistochemical stains showed a mixture of T and B cells typical for polyclonal lymphoid expansion (supplemental Figure 3).

Incidence and spectrum of fatal hematologic disorders

Most Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice died of hematologic disease by 15 months of age on a C57BL6/129Sv/jae F1 strain background. Moribund mice displayed phenotypes that were broadly characterized into 4 categories, which occurred at approximately equal frequencies: (1) MPD, (2) a disorder that was reminiscent of human MDS, (3) lymphoid expansion (hereafter referred to as lymphoproliferation), which was found concomitant with myeloid disease, and (4) histiocytic sarcoma. Mice that died of MPD showed marked peripheral leukocytosis, splenomegaly, and extensive infiltration of mature myeloid cells into hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues (supplemental Figure 4A; and data not shown). By contrast, the MDS-like disorder was characterized by normal or decreased white blood cell counts, severe anemia, mild splenomegaly, and morphologic changes consistent with dysplasia (supplemental Figure 4B; and data not shown). Lymphoproliferation was a prominent finding in the lymph nodes and lungs of a third group of mice that also showed myeloproliferation (supplemental Figure 4C). The remaining animals developed histiocytic sarcoma and displayed marked enlargement of the liver and spleen with multiple involved areas within these organs and variable involvement of the bone marrow and of other nonhematopoietic tissues (supplemental Figure 4D). Importantly, pathologic sections of the bone marrow and spleen revealed underlying myeloproliferation regardless of the assigned cause of death. Whereas mice that died with MDS had relatively short survival and those with MPD or histiocytic sarcoma showed longer latency, there was a wide range within each subgroup (data not shown).

NrasG12D expression also induced myeloproliferation in C57Bl/6 mice, but the phenotype was attenuated with median survival extended to 588 days (supplemental Figure 5A-B). Histopathologic analysis of moribund C57BL/6 mice revealed a preponderance of histiocytic sarcoma, with MPD, MDS, and lymphoproliferation occurring less often. Thus, strain background modulates both survival and the cause of death in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice.

Effects of endogenous NrasG12D expression on hematopoietic stem and progenitor populations

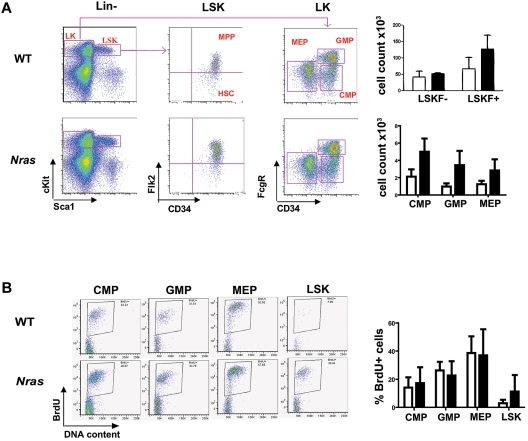

Generating Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice on a C57BL6/129Sv/jae F1 strain background allowed us to directly compare them with Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice, which have been characterized extensively in this background.17 Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice died of an aggressive MPD by the age of 4 months,17 which is remarkably different from the prolonged survival in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice. Because Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice die by the age of 4 months, we enumerated hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), multipotent progenitors (MPPs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMPs), and megakaryocytic/erythroid progenitors (MEPs) in 3- to 4-month-old Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice to compare these populations with published data from age-matched Kras mutant mice.23 Flow cytometric analysis revealed similar numbers of HSC-enriched LSKF (Lin−cKit+Sca1+Flk2−) cells in the marrows of Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D and WT mice (Figure 3A). We also detected an expansion of the MPP (Lin−cKit+Sca1+Flk2+) and immature myeloid (CMP, GMP, and MEP) populations in Nras mutant mice (Figure 3A). The spleens of Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice were infiltrated with immature hematopoietic cells, including long-term HSCs, MPPs, and myeloid progenitors (supplemental Figure 6). Labeling with BrdU revealed a similar percentage of proliferating cells within myeloid progenitor populations (CMP, GMP, and MEP) from NrasG12D and WT mice, but more cell division in the early progenitor-enriched Lin−cKit+Sca1+ (LSK) fraction in Nras mutant mice (Figure 3B). These results suggest that increased proliferation leads to the expansion of the early hematopoietic progenitors in Nras mutant animals.

Figure 3.

Effects of NrasG12D expression on hematopoietic stem cell and myeloid progenitor populations. (A) Flow cytometric analysis was performed on 3 months old F1 WT (open bars) and Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D (solid bars) bone marrow that were stained with a combination of cell surface markers to characterize HSC, MPP, CMP, GMP, and MEP populations. The absolute numbers of cells in each compartment were calculated using an established formula that estimates that 2 femurs and 2 tibiae contain 20% of total nucleated bone marrow cells.23 P values for LSKF+, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs are .0578, .0166, .0272, and .0665, respectively. (B) BrdU incorporation by hematopoietic cells enriched for myeloid progenitor activity (CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs as sorted in panel A) and for HSCs (LSK as sorted in panel A) from 3-month-old F1 WT (open bars) and Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D (solid bars) bone marrow. P value for LSK is .0596.

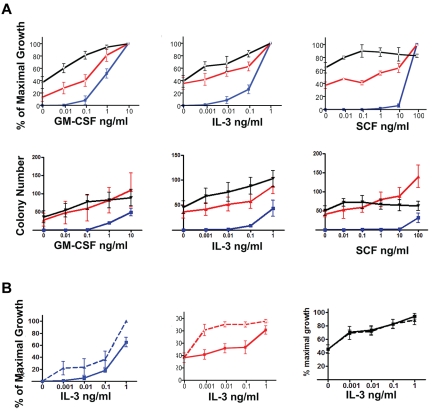

Cytokine responses of myeloid progenitors

To determine whether the distinct myeloid phenotypes in NrasG12D and KrasG12 mutant mice are associated with differential responses to cytokines, we next grew bone marrow-derived CFU-GM colonies over a range of GM-CSF, interleukin 3 (IL-3), and stem cell factor (SCF) concentrations. Nras and Kras mutant progenitors demonstrated cytokine-independent growth and hypersensitivity to GM-CSF and IL-3 (Figure 4A). KrasG12D expression was associated with a more dramatic leftward shift in the dose-response curve to GM-CSF (Figure 4A) and with much larger CFU-GM colonies in the presence of saturating concentrations of either GM-CSF or IL-3, which is consistent with the more aggressive MPD (Figure 2D; and data not shown). Interestingly, whereas higher concentrations of SCF enhanced CFU-GM growth from WT and NrasG12D bone marrow, Kras mutant cells showed no significant response (Figure 4A). Consistent with these observations, SCF and IL-3 had synergistic effects on the growth of WT and Nras, but not Kras, CFU-GM colonies (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D myeloid progenitors show distinct patterns of cytokine hypersensitivity. (A). CFU-GM colony growth from WT (blue lines), Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D (red lines), and Mx1-Cre, KrasG12D (black lines) cells in response to GM-CSF (left panel), IL-3 (middle panel), and SCF (right panel). (B). Adding SCF (10 ng/mL) to methylcellulose cultures containing a range of IL-3 concentrations revealed synergistic effects on CFU-GM growth from WT and Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D bone marrow (left and middle panels), but not Mx1-Cre, KrasG12D (right panel) marrow. The data are derived from 5 independent experiments. Well-appearing 3-month-old F1 Nras and Kras mutant mice were used.

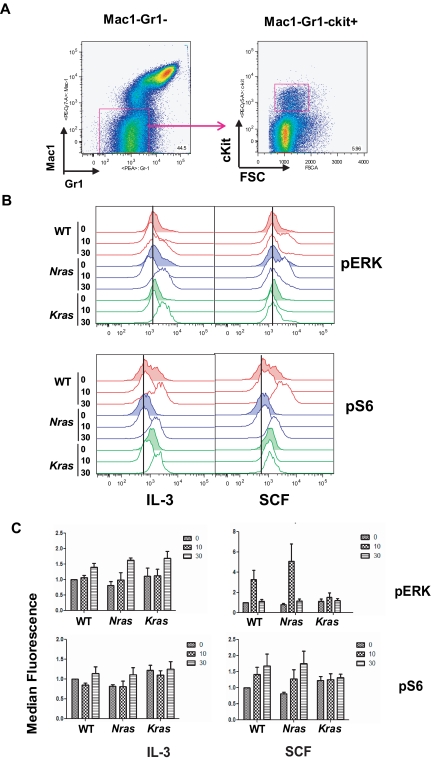

Differential activation of Ras effectors

The differential responses of Nras and Kras mutant progenitors to cytokines prompted us to look at activation of downstream Ras effectors. We performed flow cytometric analysis to measure levels of phosphorylated proteins in the Mac1−/Gr1−/c-Kit+ marrow fraction (Figure 5A), which is enriched for HSCs and progenitors.24 Analysis of Mac1−Gr1−cKit+ cells revealed a distinct pattern of basal pERK and pS6 levels and cytokine responses. The WT, Nras, and Kras mutant cells showed similar pERK levels after IL-3 stimulation (Figure 5B-5C). As previously reported,24 pERK levels increased in response to SCF in WT cells, but this induction was not observed in Kras mutant cells (Figure 5B-C). By contrast, Nras mutant cells showed a robust pERK response to SCF (Figure 5B-C). Whereas basal pS6 levels were similar in WT and Nras mutant Mac1−Gr1−cKit+ cells, they were elevated in Kras mutant cells (Figure 5B-C). IL-3 induced similar activation of pS6 in all 3 genotypes after 30 minutes; however, KrasG12D-expressing cells showed no response to SCF, whereas WT and NrasG12D increased pS6 levels. We also measured basal and cytokine-stimulated pSTAT5 and p-mTOR levels in Mac1−Gr1−cKit+ cells of all 3 genotypes and did not observe consistent differences (supplemental Figure 7A). Of note, the levels of c-Kit, which is the receptor for SCF, are similar in all 3 genotypes (supplemental Figure 7B). Together, these data demonstrate that Ras-regulated signaling networks are differentially perturbed by endogenous NrasG12D or KrasG12D expression in primary hematopoietic cells.

Figure 5.

Cytokine-induced activation of Ras effectors in Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D myeloid cells. (A) The Mac1−Gr1lowcKit+ gate was used to enrich for immature myeloid lineage cells. (B) Levels of phosphorylated ERK and S6 (pERK and pS6) were assayed in 3-month-old F1 WT, Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D, and Mx1-Cre, KrasG12D cells before and after stimulation with a saturating dose of IL-3 (50 ng/mL) or SCF (100 ng/mL) for 10 and 30 minutes. The vertical line in each panel indicates the basal level of protein phosphorylation in unstimulated WT cells. (C) Levels of pERK and pS6 were quantitated by median fluorescence signal from pFACS in panel B and compared with WT basal level, which was assigned a value of 1.

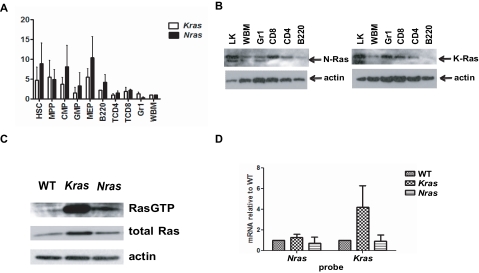

Ras expression levels and Ras-GTP levels

Because differential expression of Nras and Kras might underlie the phenotypic differences between Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D and Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice, we examined mRNA levels in WT mouse marrow. To account for the differences in the efficiency of PCR amplification, expression of Nras and Kras in whole bone marrow was normalized to a value of 1 and compared with the respective levels of Nras and Kras in different subpopulations. Nras and Kras are ubiquitously expressed in HSCs, MPPs, early myeloid progenitors (CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs), granulocytes (Gr1+ cells), B lymphocytes (B220+ cells), and in CD4 and CD8+ T lymphocytes (Figure 6A). Interestingly, early hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid restricted progenitors expressed much higher levels of both Nras and Kras compared with mature myeloid cells, which is consistent with an important role of Ras proteins in regulating cell fate decisions in HSCs and progenitors. The level of Kras, however, is significantly higher in mature myeloid cells (Gr1+ fraction). Consistent with this, K-Ras protein levels are significantly higher than N-Ras in sorted Gr1+ cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Ras expressions and protein activities. (A) Quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR was performed to determine Nras and Kras mRNA levels in normal hematopoietic cells that were sorted from bone marrow of 3-month-old WT F1 mice. Different populations were defined according to Figure 3A. The level of GAPDH was used as a loading control. The relative levels of Nras or Kras to GAPDH were determined in 4 independently sorted bone marrow samples. Expression in whole marrow (WBM) was normalized to a value of 1 for comparison with subpopulations. (B) Western blot of subpopulations from 3-month-old F1 bone marrow probed with N-Ras and K-Ras specific antibodies. Actin level was used as a loading control. (C) Activated, GTP-bound Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated from WT, Kras mutant, and Nras mutant cells and probed with pan Ras antibody (top). Total protein lysates were probed with pan Ras (middle) and actin (bottom) antibodies. (D) Quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR of Nras and Kras mRNAs from WT, Kras mutant, and Nras mutant bone marrow cells.

To extend this analysis to Nras and Kras mutant mice, we performed Western blotting and used a Raf-binding domain pulldown assay to assess Ras protein expression and levels of active, GTP-bound Ras in primary WT, Nras mutant, and Kras mutant bone marrow cells. To eliminate potential confounding effects of the different proportions of myeloid and nonmyeloid cells in WT, Nras mutant, and Kras mutant mice, we assayed Mac1+ bone marrow cells from mice of each genotype. These studies unexpectedly revealed markedly elevated levels of total Ras proteins and Ras-GTP in Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice (Figure 6C). Overall, Ras protein expression was similar in WT and Nras mutant Mac1+ cells, and the percentage of Ras-GTP was higher in Nras mutant versus WT mice (Figure 6C). Quantitative PCR analysis showed significantly higher Kras expression in KrasG12D mutant Mac1+ cells (Figure 6D), whereas the expression of Nras is similar in Mac1+ cells of all 3 genotypes. These data infer that the higher levels of Ras-GTP in Kras mutant Mac1+ cells are the result of increased K-Ras protein expression. By contrast, endogenous NrasG12D expression does not alter total Ras protein levels and is associated with a modest increase of Ras-GTP levels in myeloid lineage cells.

We also performed flow cytometric analysis to compare the levels of phosphorylated effectors in mature myeloid (Mac1+Gr1+) cells. Interestingly, despite the marked differences in Ras-GTP levels in WT, Nras mutant, and Kras mutant Mac1+ marrow, we only observed a modest increase in basal pERK levels in Kras mutant cells. Cells of all 3 genotypes that were stimulated with a saturating concentration of IL-3 increased pERK levels 30 minutes later with Kras mutant cells showing the most robust response (supplemental Figure 7C). pS6 levels increased to a similar extent in Nras and Kras mutant cells after IL-3 (supplemental Figure 7C). Kras mutant cells also showed higher pSTAT5 levels than Nras mutant or WT cells. Whereas the basal level of pmTOR in Kras mutant cells was higher than Nras mutant or WT cells, there was a minimal response to IL-3 in cells of all 3 genotypes (supplemental Figure 7C).

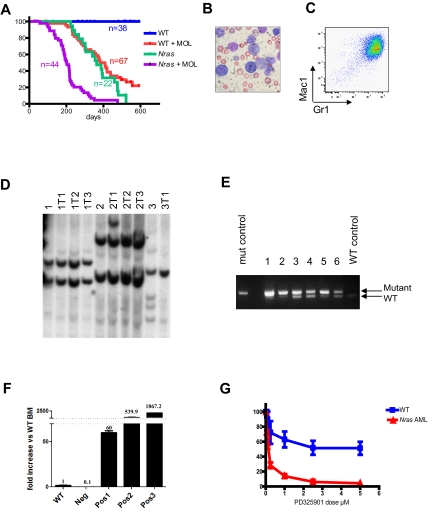

Retroviral mutagenesis induces AML in Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice

To identify genes that might cooperate with NrasG12D expression in leukemogenesis, we injected Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice with the MOL4070LTR retrovirus shortly after birth and administered a single dose of poly I:C at weaning. This protocol induced AML in 30 of 32 Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D animals (Figure 7A). The blood of affected mice contained myeloblasts (Figure 7B) that expressed myeloid lineage markers (Figure 7C) and had a morphologic appearance that is most similar to the French-American-British M4/M5 subtype of human AML (Figure 7B; and data not shown). These leukemias demonstrated a clonal pattern of retroviral integrations (Figure 7D), and many also showed complete or partial loss of the WT Nras allele (Figure 7E). Biochemical analysis revealed hyperactivation of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways in most of these AMLs (supplemental Figure 8). However, this pattern was not uniform, and a subset of the AMLs that developed in Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice demonstrated PI3K pathway activation but attenuated Raf/MEK/ERK signaling.

Figure 7.

NrasG12D cooperates with MOL4070LTR to induce AML. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of WT and Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D pups that were injected with MOL4070LTR (+MOL) and of littermate controls that did not receive this virus (−MOL). Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice in the +MOL cohort show significantly shorter survival than WT littermates +MOL (P < .0001) or the Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D −MOL group ( < .0001). (B) Blood smear from a Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mouse with AML. Slides were examined by Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope with 40×/0.75 NA oil objective. Picture was taken with Nikon Coolpix 5000 camera and analyzed with Adobe Photoshop CS3. (C) Flow cytometry demonstrating Mac1 and Gr1 expression on myeloblasts. (D) Southern blot analysis with a probe to the MOL4070 LTR sequences demonstrates that Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D leukemias are clonal. Primary AMLs (1, 2, and 3) were transplanted into sublethally irradiated recipients (labeled as 1T1, etc). (E) Semiquantitative PCR with primers that amplify both WT and mutant Nras allele demonstrates the loss of the WT allele in most Nras mutant AMLs (the amplification product corresponding to the WT Nras allele is not visible in lanes 1 and 2, and greatly reduced in intensity in lanes 3, 5, and 6). (F) Evi1 expression measured by quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR in WT whole bone marrow (WT), AML that does not have Evi1 integration (Neg), and 3 AMLs that harbor Evi1 integrations (Pos1, Pos2, and Pos3). The level of Evi1 was normalized to expression of GAPDH and presented as fold increase compared with the level in the WT whole bone marrow. Error bars represent SD from triplicates. (G) Blast colony growth from Nras mutant AMLs (red line) is hypersensitive to the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 compared with CFU-GM colony growth from WT marrow (blue line). Colony growth was assayed in methylcellulose cultures containing a saturating dose of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) over a range of PD0325901 concentrations.

Sublethally irradiated recipients that are transplanted with MOL4070LTR-induced leukemias develop AML with similar phenotypic features and the same clonal pattern of proviral restriction fragments seen in primary mice (Figure 7D). We performed linker-mediated PCR and DNA sequencing to identify MOL4070LTR integrations in a pilot group of 6 NrasG12D AMLs. Analysis of 87 independent viral insertion sites revealed 5 common insertion sites that appeared in at least 2 independent AMLs (supplemental Table 1). One common insertion site (Evi1) was identified in 5 of 6 leukemias. The insertion sites in these AMLs were uniformly identified in the “sense” orientation 5′ of Evi1 and were associated with a 60- to 1800-fold increase in expression (Figure 7F).

In a model of AML initiated by hyperactive Ras signaling resulting from inactivation of the Nf1 tumor suppressor in which MOL4070LTR induces cooperating mutations, progression from MPD to AML is associated with enhanced in vitro and in vivo sensitivity to MEK inhibitors.22 Similarly, we found that blast colony formation from Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D AMLs is abrogated at markedly lower concentrations of the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 compared with normal myeloid progenitor growth (Figure 7G).

Discussion

The prevalence of NRAS mutations in hematopoietic cancers stimulated efforts to generate mouse models for biologic and preclinical studies. Mice in which NrasG12D was expressed under the control of the hMRP8 promoter or through a Vav-tTA/TRE2 transgene showed impaired neutrophil maturation and aggressive systemic mastocytosis, respectively.28,29 Coexpressing NrasG12D with myeloid fusion oncogenes (PEBP2β-MYH11 or Mll-Af9) or with BCL-2 induced MDS and AML.28,30,31 These variable phenotypes probably reflect the promoters used to drive NrasG12D expression and the modifying effects of broadly expressing different cooperating mutations. Other groups used a retroviral transduction/transplantation approach to investigate the transforming potential of NrasG12D. In one study, expressing oncogenic Nras under the Moloney murine leukemia virus LTR induced myeloid malignancies with prolonged latency and incomplete penetrance.32 More recently, Parikh et al33 engineered retroviral vectors in the murine stem cell leukemia backbone in which they expressed a green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker gene immediately after the viral LTR followed by an internal ribosomal entry site preceding NrasG12D. Transplanting irradiated recipients with bone marrow cells that were infected with this MSCV-GFP-IRES-NrasG12D vector rapidly caused a CMML-like MPD or AML.33 Importantly, all of these malignancies harbored clonal murine stem cell leukemia integrations, which infers the need for cooperating mutations in vivo. Taken together, whereas data from transgenic and retroviral transduction/transplantation experiments indicate that oncogenic Nras initiates leukemic growth under some experimental conditions, it has not been possible to distinguish NrasG12D intrinsic phenotypes or to directly assess the functional output of endogenous NrasG12D expression in hematopoietic cells.

We generated Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice to determine whether endogenous NrasG12D expression is sufficient to initiate malignant hematologic disease and to assess the effects of endogenous NrasG12D expression on hematopoiesis. Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice show extended survival and ultimately die of a spectrum of hematologic malignancies. Whereas these mice do not spontaneously develop acute leukemia, endogenous NrasG12D cooperates strongly with the MOL4070LTR virus to induce AML. Analysis of young Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice revealed intrinsic cellular and biochemical effects of oncogenic Nras expression in hematopoietic cells, but it is unclear whether secondary mutations that lead to clonal outgrowth contribute to the development of fatal MPD and MDS. The long latency and variable spectrum of malignant hematologic disease suggest the need for cooperating mutations.

We unexpectedly observed that the myeloid phenotype is greatly attenuated in Mx1-Cre, LSL-NrasG12D mice compared with Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D animals, which uniformly die of an aggressive MPD by 3 to 4 months of age.17,18 Endogenous NrasG12D expression also had less pronounced effects on steady-state hematopoiesis than KrasG12D in age-matched mice. Whereas KrasG12D and NrasG12D hematopoietic progenitors form cytokine-independent CFU-GM in methylcellulose medium, Nras mutant cells are more dependent on growth factors, and the morphology of colonies grown in the presence of saturating concentrations of GM-CSF and IL-3 is normal. The differential response of Kras and Nras mutant progenitors to SCF further suggests that KrasG12D expression has more severe functional consequences. Whereas SCF acts synergistically with IL-3 or GM-CSF to promote WT and NrasG12D CFU-GM growth, it does not further augment the profoundly hypersensitive growth of KrasG12D progenitors.

Flow cytometric analysis of WT, Nras mutant, and Kras mutant hematopoietic cells revealed discrete differences in basal phosphorylation of Ras effectors and variable responses to cytokine stimulation, which did not reflect Ras-GTP levels. These findings are consistent with the emerging view that primary cells remodel signaling networks in response to oncoprotein expression. We also observed greatly increased Ras-GTP levels in Mac1+ cells from Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice, which suggests that endogenous KrasG12D expression initiates a “feed forward” loop in myeloid lineage cells that increases the levels of oncogenic K-Ras and Ras-GTP. We speculate that this, in turn, contributes to the more aggressive MPD in Mx1-Cre, LSL-KrasG12D mice. However, differential expression of Nras and Kras does not readily explain all the differences we observed. The distinct patterns of effector phosphorylation and cytokine responses suggest intrinsic differences in N-RasG12D and K-RasG12D, which probably result from differential posttranslational modifications of their hypervariable domains.34,35 These modifications regulate intracellular trafficking and target N-Ras and K-Ras to distinct microdomains of the plasma membrane and other endomembranes,4,34–38 Differential subcellular localization of N-Ras and K-Ras probably modulates access to upstream regulators and downstream effectors and could lead to activation of distinct signaling pathways. Consistent with this idea, a recent study revealed that the hypervariable domains of oncogenic K-Ras and H-Ras regulate self-renewal versus differentiation fates in the F9 mouse embryonal stem cell model.39

Experimental data support the idea that AML is frequently initiated by a transcription factor fusion (class 1 mutation) but also requires a cooperating class 2 mutation that deregulates cellular signaling networks.40 Consistent with this idea, some AML specimens contain subclones with independent RAS mutations, and RAS mutations that are detected at diagnosis may disappear over time.13,41,42 We designed our screen to model this proposed pathogenic sequence by first injecting neonatal mice, and inducing NrasG12D expression 3 weeks later by administering poly I:C. Using this strategy, we found that the Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice developed AML with more than 90% penetrance. Importantly, these leukemias resemble the M4 and M5 subtypes of human AML, which show the highest frequency of NRAS mutations.15,16 We also demonstrated selection for clones that have deleted the normal Nras allele, and found that this system reliably identified authentic cooperating genes. Evi-1 was detected as a common insertion site in Nras AMLs. EVI-1 encodes a zinc finger transcription factor that functions in stem cell renewal and is the target of multiple different chromosomal rearrangements in human AMLs, including the t,(3,3) inv(3), t(3;21), t(3;8), and t(3,12). Importantly, 2 large series of mutational analysis of human AML samples revealed an association between NRAS mutations and translocations that deregulate EVI-1 expression.15,16 By contrast, Mx1-Cre, KrasG12D pups that were injected with the same MOL4070LTR viral stock and treated with an identical poly I:C protocol did not spontaneously developed acute leukemia before dying from MPD at approximately 4 months of age.21 Transplanting bone marrow from these animals induced AML in a small percentage of the recipients, with the majority developing T lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia with prolonged latency.21

Together, these observations raise the question of how to reconcile the profound effects of KrasG12D expression in the myeloid compartment with the potent ability of a “weaker” NrasG12D mutation to cooperate in AML induction. We speculate that this may be true because KrasG12D drives cellular proliferation and differentiation so strongly that it does not cooperate effectively with mutations that perturb self-renewal. By contrast, our data infer that NrasG12D expression confers a proliferative and survival advantage that does not overwhelm the ability of cooperating genes to simultaneously enhance self-renewal and block differentiation.

Chemical carcinogenesis experiments demonstrated loss of the WT Hras or Kras alleles in mouse skin and lung tumors.43 Our data extend this paradigm to a model that involves spontaneous loss of the normal Nras allele in retrovirally induced AML. The emerging genetic evidence that normal Ras alleles have tumor suppressor activity is supported by limited functional data.44,45 Because oncogenic Ras proteins accumulate in the GTP-bound conformation and should therefore markedly out-compete their normal counterparts for access to effectors, it is unclear how loss of the WT allele confers a growth advantage in vivo. Genetically accurate mouse cancer models provide new tools for addressing this fundamental question.

We have comprehensively characterized the consequences of endogenous NrasG12D expression in hematopoietic cells and obtained disease phenotypes that model the spectrum of myeloid malignancies associated with NRAS mutations in human patients. MOL4070LTR-induced AMLs from Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice can also be used to test targeted and conventional cytotoxic agents, and the retroviral insertions in these leukemias provide molecular sequence tags for indentifying candidate genes that modulate drug response and resistance.22 A recent screen that identified STK33 as synthetic lethal with oncogenic KRAS, but not NRAS, in myeloid leukemia and epithelial cancer cell lines underscores the functional importance of isoform-specific differences.46 Mx1-Cre, NrasG12D mice provide a robust and tractable platform for addressing the molecular mechanisms underlying these differences and for approaching the central problem of how to effectively interfere with oncogenic Ras signaling in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emmanuelle Passegue and Ernesto Diaz-Flores for advice and assistance with flow cytometry experiments, David Largaespada for help with retroviral insertional mutagenesis, and Judith Leopold (Pfizer Inc) for PD0325901.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants U01 CA84221, R37 CA72614, K01 CA118425, K08 CA134649, K08 CA119105, and T32 CA129583), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, the Jeffrey and Karen Peterson Family Foundation, and the Frank A. Campini Foundation. T.J. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.C.K. is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar. The Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research supports research in the laboratory of L.W.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: Q.L. designed experiments, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; A.M. and E.H.-T. maintained the mice and performed research; S.C.K. analyzed the pathologic specimens and assisted in writing and editing the manuscript; K.A. performed bioinformatic analysis of retroviral insertions and assisted in writing and editing the manuscript; J.C.Y.W. performed research studies and analyzed data; B.S.B. provided assistance of HSCs analysis and FACS sorting and assisted in writing and editing the manuscript; L.W. developed MOL4070LTR retroviral strain for mutagenesis and provided essential reagents; K.M.H and T.J. developed NrasG12D knock-in mice and assisted in writing and editing the manuscript; and K.S. designed the experiments, reviewed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation of Q.L. is Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Correspondence: Kevin Shannon, Helen Diller Family Cancer Research Building, University of California San Francisco, 1450 3rd St, Rm 240, San Francisco, CA 94158-9001; e-mail: shannonk@peds.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science. 2001;294(5545):1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129(5):865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mor A, Philips MR. Compartmentalized Ras/MAPK signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:771–800. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donovan S, Shannon KM, Bollag G. GTPase activating proteins: critical regulators of intracellular signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602(1):23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potenza N, Vecchione C, Notte A, et al. Replacement of K-Ras with H-Ras supports normal embryonic development despite inducing cardiovascular pathology in adult mice. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(5):432–437. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson L, Mercer K, Breenbaum D, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15(24):3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerra C, Mijimolle N, Dhawahir A, et al. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haigis KM, Kendall KR, Wang Y, et al. Differential effects of oncogenic K-Ras and N-Ras on proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression in the colon. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):600–608. doi: 10.1038/ngXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padua RA, Carter G, Hughes D, et al. RAS mutations in myelodysplasia detected by amplification, oligonucleotide hybridization, and transformation. Leukemia. 1988;2(8):503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onida F, Kantarjian HM, Smith TL, et al. Prognostic factors and scoring systems in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a retrospective analysis of 213 patients. Blood. 2002;99(3):840–849. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacher U, Haferlach T, Schoch C, Kern W, Schnittger S. Implications of NRAS mutations in AML: a study of 2502 patients. Blood. 2006;107(10):3847–3853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen DT, Frew ME, Hills R, et al. RAS mutation in acute myeloid leukemia is associated with distinct cytogenetic subgroups but does not influence outcome in patients younger than 60 years. Blood. 2005;106(6):2113–2119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, et al. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(2):597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307203101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan IT, Kutok JL, Williams IR, et al. Conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras from its endogenous promoter induces a myeloproliferative disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(4):528–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff L, Koller R, Hu X, Anver MR. A Moloney murine leukemia virus-based retrovirus with 4070A long terminal repeat sequences induces a high incidence of myeloid as well as lymphoid neoplasms. J Virol. 2003;77(8):4965–4971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4965-4971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akagi K, Suzuki T, Stephens RM, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. RTCGD: retroviral tagged cancer gene database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D523–D527. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dail M, Li Q, McDaniel A, et al. Mutant Ikzf1, KrasG12D, and Notch1 cooperate in T lineage leukemogenesis and modulate responses to targeted agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(11):5106–5111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001064107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauchle JO, Kim D, Le DT, et al. Response and resistance to MEK inhibition in leukaemias initiated by hyperactive Ras. Nature. 2009;461(7262):411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature08279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passegue E, Wagner EF, Weissman IL. JunB deficiency leads to a myeloproliferative disorder arising from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2004;119(3):431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Meter ME, Diaz-Flores E, Archard JA, et al. K-RasG12D expression induces hyperproliferation and aberrant signaling in primary hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109(9):3945–3952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Liu Y, Beard C, et al. Expression of oncogenic K-ras from its endogenous promoter leads to a partial block of erythroid differentiation and hyperactivation of cytokine-dependent signaling pathways. Blood. 2007;109(12):5238–5241. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Socolovsky M, Gross AW, Lodish HF. Role of Ras signaling in erythroid differentiation of mouse fetal liver cells: functional analysis by a flow cytometry-based novel culture system. Blood. 2003;102(12):3938–3946. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun BS, Archard JA, Van Ziffle JA, Tuveson DA, Jacks TE, Shannon K. Somatic activation of a conditional KrasG12D allele causes ineffective erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2006;108(6):2041–2044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kogan SC, Lagasse E, Atwater S, et al. The PEBP2betaMYH11 fusion created by Inv(16)(p13;q22) in myeloid leukemia impairs neutrophil maturation and contributes to granulocytic dysplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(20):11863–11868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiesner SM, Jones JM, Hasz DE, Largaespada DA. Repressible transgenic model of NRAS oncogene-driven mast cell disease in the mouse. Blood. 2005;106(3):1054–1062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omidvar N, Kogan S, Beurlet S, et al. BCL-2 and mutant NRAS interact physically and functionally in a mouse model of progressive myelodysplasia. Cancer Res. 2007;67(24):11657–11667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim WI, Matise I, Diers MD, Largaespada DA. RAS oncogene suppression induces apoptosis followed by more differentiated and less myelosuppressive disease upon relapse of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(5):1086–1096. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacKenzie KL, Dolnikov A, Millington M, Shounan Y, Symonds G. Mutant N-ras induces myeloproliferative disorders and apoptosis in bone marrow repopulated mice. Blood. 1999;93(6):2043–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parikh C, Subrahmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS rapidly and efficiently induces CMML- and AML-like diseases in mice. Blood. 2006;108(7):2349–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvius JR. Mechanisms of Ras protein targeting in mammalian cells. J Membr Biol. 2002;190(2):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancock JF. Ras proteins: different signals from different locations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrm1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rocks O, Peyker A, Bastiaens PI. Spatio-temporal segregation of Ras signals: one ship, three anchors, many harbors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abankwa D, Gorfe AA, Hancock JF. Ras nanoclusters: molecular structure and assembly. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(5):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian T, Harding A, Inder K, Plowman S, Parton RG, Hancock JF. Plasma membrane nanoswitches generate high-fidelity Ras signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(8):905–914. doi: 10.1038/ncb1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinlan MP, Quatela SE, Philips MR, Settleman J. Activated Kras, but not Hras or Nras, may initiate tumors of endodermal origin via stem cell expansion. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(8):2659–2674. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01661-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly L, Clark J, Gilliland DG. Comprehensive genotypic analysis of leukemia: clinical and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14(1):10–18. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farr CJ, Saiki RK, Erlich HA, McCormick F, Marshall CJ. Analysis of RAS gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia by polymerase chain reaction and oligonucleotide probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(5):1629–1633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bashey A, Gill R, Levi S, et al. Mutational activation of the N-ras oncogene assessed in primary clonogenic culture of acute myeloid leukemia (AML): implications for the role of N-ras mutation in AML pathogenesis. Blood. 1992;79(4):981–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z, Wang Y, Vikis HG, et al. Wildtype Kras2 can inhibit lung carcinogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 2001;29(1):25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.To MD, Wong CE, Karnezis AN, Del Rosario R, Di Lauro R, Balmain A. Kras regulatory elements and exon 4A determine mutation specificity in lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1240–1244. doi: 10.1038/ng.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz R, Lue J, Mathews J, et al. Inhibition of Ras oncogenic activity by Ras protooncogenes. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(2):241–248. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scholl C, Frohling S, Dunn IF, et al. Synthetic lethal interaction between oncogenic KRAS dependency and STK33 suppression in human cancer cells. Cell. 2009;137(5):821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.