Abstract

Purpose

Patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are at elevated risk of second primary malignancies (SPM), most commonly of the head and neck (HN), lung, and esophagus. Our objectives were to identify HNSCC subsite-specific differences in SPM risk and distribution and to describe trends in risk over 3 decades, before and during the era of human papillomavirus (HPV) –associated oropharyngeal SCC.

Methods

Population-based cohort study of 75,087 patients with HNSCC in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. SPM risk was quantified by using standardized incidence ratios (SIRs), excess absolute risk (EAR) per 10,000 person-years at risk (PYR), and number needed to observe. Trends in SPM risk were analyzed by using joinpoint log-linear regression.

Results

In patients with HNSCC, the SIR of second primary solid tumor was 2.2 (95% CI, 2.1 to 2.2), and the EAR was 167.7 cancers per 10,000 PYR. The risk of SPM was highest for hypopharyngeal SCC (SIR, 3.5; EAR, 307.1 per 10,000 PYR) and lowest for laryngeal SCC (SIR, 1.9; EAR, 147.8 per 10,000 PYR). The most common SPM site for patients with oral cavity and oropharynx SCC was HN; for patients with laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, it was the lung. Since 1991, SPM risk has decreased significantly among patients with oropharyngeal SCC (annual percentage change in EAR, −4.6%; P = .03).

Conclusion

In patients with HNSCC, the risk and distribution of SPM differ significantly according to subsite of the index cancer. Before the 1990s, hypopharynx and oropharynx cancers carried the highest excess risk of SPM. Since then, during the HPV era, SPM risk associated with oropharyngeal SCC has declined to the lowest risk level of any subsite.

INTRODUCTION

Second primary malignancy (SPM) represents the leading long-term cause of mortality in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).1 Approximately one third of HNSCC deaths are attributable to SPMs,2,3 triple the number of deaths that are a result of distant metastases.4

SPMs after HNSCC illustrate concepts of field cancerization, in which environmental carcinogens, such as tobacco and alcohol, may induce a field of mucosa afflicted with premalignant disease and may elevate epithelial cancer risk throughout the upper aerodigestive tract.5,6 SPMs also provide information regarding common etiologies and epidemiologic trends.7,8 The canonical sites of elevated SPM risk after an index HNSCC are the head and neck, lung, and esophagus (HNLE sites).2,3,6,7,9–17

HNSCC is a heterogeneous disease that has variation across subsites (oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, or hypopharynx) in many characteristics: age, sex, ethnicity, N and M classification, histologic grade, treatment modality, and prognosis. Recent data from international case-control studies have demonstrated that the risk of HNSCC attributable to tobacco and alcohol exposure differs by HNSCC subsite; alcohol is most strongly associated with risk for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers, and tobacco is most strongly associated with risk of laryngeal cancers.18–20 Oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) has recently been etiologically associated with the majority of oropharyngeal cancers and is associated with improved survival compared with non-HPV associated HNSCC.21–23

Therefore, HNSCC subsites may also differ in levels of SPM risk and in the distributions of SPM location. The risk of SPM in the era of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer is unknown. Data regarding subsite-specific risks and trends over time may be helpful in the rational application of surveillance of HNSCC patients after treatment of the index cancer.

The objective of this study was to characterize SPM risks by HNSCC subsite and time period in a large U.S. cohort of patients with HNSCC who had near-universal follow-up. We hypothesized that risks of SPM would differ by HNSCC subsite and would have changed over time, associated with the emergence of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC.

METHODS

Cases in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

The National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program has collected data continuously since 1973 and now captures 26% of cancers in the United States. All cancers, primary and subsequent, occurring among residents of defined geographical registries comprising the SEER program are reportable. Near-universal follow-up is achieved by actively tracing all patients. A limitation of cancer incidence registries such as SEER is lack of information on risk factors, such as tobacco use, alcohol use, or HPV status. Quality control is an integral part of the SEER program, and comparison studies have confirmed that pathologic, surgical, and radiation data are accurately recorded.24,25 The National Cancer Institute does not require institutional board approval for use of this deidentified data set.

The study population was drawn from patients diagnosed with HNSCC between 1975 and 2006 (accounting for delayed entry of the Seattle and Atlanta registries) within the nine original SEER registries, which represent a cross-section of the U.S. population with respect to race, ethnicity, income, and educational level.26 All patients with an index invasive SCC (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition27 histology codes 8070-8076, 8078) arising from subsites of the head and neck (oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx) were included.

Definition of SPM Risk

SPM was defined as a metachronous invasive solid cancer developing ≥ 6 months after an index HNSCC, under criteria of Warren and Gates28 as modified by the National Cancer Institute.29 If the second cancer was of non-squamous cell origin, or if it developed in a different location, it was coded as an SPM. If the second cancer was SCC and developed in the same region as the index cancer, it was only coded as an SPM if greater than 60 months had passed since the index diagnosis. Occurrences defined in primary medical records as either recurrent or metastatic were excluded. These criteria are intended to be conservative and to minimize classification of recurrences as SPMs.

The crude incidence of SPM is not informative, as it simply reflects the number of cancers developing in the cohort, irrespective of censoring or the expected number of cancers; therefore, the risk of SPM was defined as the standardized incidence ratio (SIR), described by Schoenberg and Myers30 and adapted to cancer registry analysis by Begg.31 SIR was defined as the ratio of observed to expected (O/E) second cancers, in which the number of cancers expected was calculated for a reference SEER cohort of identical age, sex, ethnicity, and time period.

The excess absolute risk (EAR) represents the absolute number of additional subsequent cancers attributable to the index HNSCC. EAR is calculated as the excess (observed – expected) number of second cancers in patients with an index HNSCC per 10,000 person-years at risk (PYR).29

In our study, SIR and EAR account for the number of patients at risk, as patients are lost to follow-up or die. SIR is a relative measure of the strength of association between two cancers, whereas EAR is an absolute measure of the clinical burden of additional cancer occurrences in a given population. The number needed to observe is calculated from EAR, and it represents the number of patients who would need to be observed for 1 year to observe one additional occurrence of SPM beyond the number of malignancies expected in the reference population.

Statistical Methods

Patient and tumor characteristics for patients with HNSCC occurrences arising in various subsites were compared by using analysis of variance and χ2 statistics, with an a priori level of α = .05. Confidence intervals for SIR were calculated with Byar's approximation to the Poisson distribution.32 Considering multiple comparisons, SIR values were considered significantly elevated at P < .01.

To determine changes in excess SPM burden over time, the trend in EAR was analyzed for each HNSCC subsite. Occurrences were binned by year of diagnosis (ie, 1975 to 1979, 1980 to 1984, 1985 to 1990, 1991 to 1995, 1996 to 2000, 2001 to 2006). EAR was limited to risk for the first 5 years from index HNSCC diagnosis, to limit heterogeneity in length of follow-up across period cohorts. Trends in EAR were calculated by using joinpoint regression, a variant of log-linear regression used in the analysis of trends in cancer incidence.33 In this technique, a segmented trend line is fitted in an unsupervised fashion by using a permutation test to determine the most parsimonious number of joinpoints. SIR and EAR values were calculated in SEERStat release 6.5.2 (2009; National Cancer Institute Cancer Statistics Branch, Bethesda, MD). Joinpoint regression was performed in Joinpoint 3.4.3 (2010; National Cancer Institute Statistical Research Applications Branch, Bethesda, MD). Additional statistical analyses were performed by using SAS 9.2 (2008; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 75,087 occurrences of HNSCC were identified by subsite in the SEER registry between 1975 and 2006. Patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up time for patients with HNSCC was 69.1 months, and 1,140 patients (1.5%) were lost to follow-up. When occurrences by subsite were compared on patient and tumor characteristics, including follow-up time, loss to follow-up, age, sex, ethnicity, N and M classification, treatment modality, and histologic grade, there were significant differences between subsites on all parameters (P < .001), which reflects the heterogeneity of head and neck cancer across subsites.

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics by Head and Neck Subsite

| Characteristic | Patients by Subsite |

P | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Sites |

Oral Cavity |

Oropharynx |

Larynx |

Hypopharynx |

|||||||

| No. (N = 75,087) | %(100%) | No. (n = 36,107) | %(48.1%) | No. (n = 8,440) | %(11.2%) | No. (n = 25,624) | %(34.1%) | No. (n = 4,916) | %(6.5%) | ||

| Median follow-up time, months | 69.1 | 68.2 | 55.5 | 79.9 | 43.3 | < .001 | |||||

| Lost to follow-up | 1,140 | 1.5 | 600 | 1.7 | 148 | 1.8 | 374 | 1.5 | 18 | 0.4 | < .001 |

| Median age, years | 63.4 | 63.9 | 59.9 | 64.1 | 63.2 | < .001 | |||||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 72,300 | 75.6 | 32,725 | 71.0 | 7,525 | 73.2 | 27,310 | 82.3 | 4,740 | 78.1 | |

| Female | 23,338 | 24.4 | 13,377 | 29.0 | 2,755 | 26.8 | 5,877 | 17.7 | 1,329 | 21.9 | < .001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| White | 82,304 | 86.1 | 40,915 | 88.7 | 8,567 | 83.3 | 27,993 | 84.3 | 4,829 | 80.0 | |

| Black | 9,971 | 10.4 | 3563 | 7.7 | 1,373 | 13.4 | 4,127 | 12.4 | 908 | 14.9 | |

| Other | 3,363 | 3.5 | 1624 | 3.5 | 340 | 3.3 | 1,067 | 3.2 | 332 | 5.4 | < .001 |

| N and M classification | |||||||||||

| N0 M0 | 39,265 | 47.0 | 20,918 | 51.3 | 1,908 | 20.4 | 15,356 | 54.9 | 1,083 | 19.6 | |

| N+ M0 | 35,434 | 42.4 | 16,093 | 39.5 | 5,972 | 63.9 | 9,940 | 35.5 | 3,429 | 62.1 | |

| Any N M1 | 8,909 | 10.7 | 3743 | 9.2 | 1,466 | 15.7 | 2,693 | 9.6 | 1,007 | 18.2 | < .001 |

| Treatment modality | |||||||||||

| Surgery alone | 35,435 | 54.1 | 24,104 | 68.5 | 1,727 | 23.7 | 8,696 | 36.9 | 908 | 21.5 | |

| S + RT | 23,158 | 35.3 | 8,399 | 23.9 | 3,546 | 48.8 | 9,004 | 38.2 | 2,209 | 52.4 | |

| RT alone | 6,942 | 10.6 | 4,500 | 12.8 | 1,998 | 27.5 | 5,843 | 24.8 | 1,099 | 26.1 | < .001 |

| Histologic grade | |||||||||||

| Well | 17,077 | 24.5 | 10,247 | 31.1 | 862 | 11.0 | 5,521 | 22.7 | 447 | 9.7 | |

| Moderately | 33,163 | 47.5 | 15,156 | 46.0 | 3,468 | 44.3 | 12,321 | 50.6 | 2,218 | 48.0 | |

| Poor | 17,978 | 25.8 | 6,926 | 21.0 | 3,274 | 41.8 | 5,924 | 24.3 | 1,854 | 40.1 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1,529 | 2.2 | 600 | 1.8 | 230 | 2.9 | 592 | 2.4 | 107 | 2.3 | < .001 |

NOTE. P values represent subsite comparisons on analysis of variance or χ2 tests.

Abbreviations: S + RT, surgery and postoperative radiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

The crude nonactuarial incidence and location of second primary malignancy (SPM) differed significantly between subsites (P < .001), as detailed in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Because crude SPM incidence data do not adjust for the expected number of cancers in a reference population or for the number of patients at risk, SIR and EAR of SPM were calculated (Table 2). Among patients with HNSCC, the SIR of second solid tumor was 2.2 (95% CI, 2.1 to 2.2), corresponding to 167.7 excess (ie, EAR) second solid cancers per 10,000 PYR. The highest relative risk of SPM was observed for second head and neck cancer (SIR, 12.4; 95% CI, 12.0 to 12.7). Excess burden of disease, as measured by EAR, was highest for lung (75.2 excess cases per 10,000 PYR), followed by head and neck (59.8 excess cases per 10,000 PYR), and then esophageal cancer (14.2 excess cases per 10,000 PYR).

Table 2.

Elevated Risk of SPM by Site of Index HNSCC

| SPM Site | All HN Primaries |

Oral Cavity Primaries |

Oropharynx Primaries |

Larynx Primaries |

Hypopharynx Primaries |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIR |

EAR per 10,000 PYR | SIR |

EAR per 10,000 PYR | SIR |

EAR per 10,000 PYR | SIR |

EAR per 10,000 PYR | SIR |

EAR per 10,000 PYR | ||||||

| Rate | 95% CI | Rate | 95% CI | Rate | 95% CI | Rate | 95% CI | Rate | 95% CI | ||||||

| All solid tumors | 2.18 | 2.15 to 2.21 | 167.74 | 2.82 | 2.74 to 2.90 | 228.73 | 2.99 | 2.88 to 3.10 | 209.78 | 1.92 | 1.88 to 1.97 | 147.78 | 3.47 | 3.27 to 3.68 | 307.06 |

| Lung and bronchus | 3.75 | 3.66 to 3.85 | 75.22 | 3.96 | 3.74 to 4.20 | 69.07 | 4.86 | 4.54 to 5.20 | 79.59 | 4.07 | 3.92 to 4.22 | 93.83 | 6.06 | 5.46 to 6.71 | 139.52 |

| HN | 12.38 | 12.03 to 12.74 | 59.76 | 26.16 | 24.92 to 27.44 | 115.91 | 22.21 | 20.80 to 23.70 | 83.73 | 5.80 | 5.42 to 6.19 | 29.34 | 18.94 | 16.74 to 21.35 | 83.73 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx | 15.25 | 14.78 to 15.73 | 54.29 | 31.68 | 30.08 to 33.33 | 105.21 | 26.73 | 24.9 to 28.65 | 75.46 | 7.25 | 6.74 to 7.77 | 26.47 | 23.69 | 20.76 to 26.91 | 80.27 |

| Oropharynx | 18.22 | 15.36 to 21.47 | 1.83 | 28.04 | 19.84 to 38.49 | 2.73 | 40.16 | 28.42 to 55.12 | 3.56 | 11.24 | 7.92 to 15.49 | 1.32 | 32.15 | 15.42 to 59.12 | 2.48 |

| Larynx | 5.03 | 4.64 to 5.43 | 6.44 | 10.50 | 9.14 to 11.99 | 12.56 | 9.42 | 7.86 to 11.20 | 9.06 | 2.24 | 1.86 to 2.68 | 2.83 | 7.79 | 5.51 to 10.69 | 5.34 |

| Hypopharynx | 16.53 | 15.04 to 18.13 | 5.54 | 28.56 | 23.90 to 33.87 | 8.73 | 38.93 | 32.20 to 46.66 | 9.19 | 9.81 | 8.09 to 11.78 | 3.73 | 11.68 | 6.22 to 19.97 | 4.67 |

| Esophagus | 8.35 | 7.86 to 8.87 | 14.24 | 15.05 | 13.44 to 16.80 | 22.95 | 15.70 | 13.68 to 17.94 | 20.95 | 4.69 | 4.12 to 5.30 | 8.65 | 28.63 | 24.02 to 33.87 | 51.78 |

| All non-HNLE sites | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.09 | 10.38 | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.10 | 9.40 | 1.12 | 1.03 to 1.22 | 14.38 | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.10 | 10.40 | 1.10 | 0.98 to 1.24 | 13.86 |

Abbreviations: SPM, second primary malignancy; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HN, head and neck; SIR, standardized incidence ratio; EAR, excess absolute risk; PYR, person-years at risk; HNLE, head and neck, lung, and esophagus.

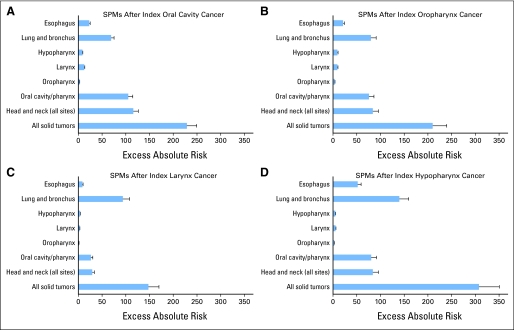

The risk of SPM differed significantly by subsite of index HNSCC (Table 2; Fig 1). The SIR of a second solid tumor at any site was highest for patients with an index hypopharynx SCC (3.5; 95% CI, 3.3 to 3.7), followed by oropharynx (3.0; 95% CI, 2.9 to 3.1), oral cavity (2.8; 95% CI, 2.7 to 2.9), and larynx (1.9; 95% CI, 1.9 to 2.0; P < .001). Similarly, the absolute number of excess second solid cancers per 10,000 PYR was highest in patients with an index hypopharyngeal SCC (307.1), and lowest for index larynx SCC (147.8; P < .001).

Fig 1.

Excess absolute risk of second primary malignancy (SPM), by site of index head and neck cancer: (A) index oral cavity, (B) index oropharynx, (C) index larynx, and (D) index hypopharynx cancer.

For most subsites, the SIR values for SPM of the head and neck were 15- to 30-fold greater than expected, whereas SIRs for lung cancer were elevated by about four-fold. In oral cavity and oropharynx primary cancers, the highest number of excess SPMs occurred in the head and neck. In larynx and hypopharynx primary cancers, the highest number of excess SPMs occurred in the lung. Additional context for EAR values is provided by the number needed to observe, representing the number of patients who would need to observed for 1 year to observe one additional SPM, at that site (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients Required for 1 Year of Observation to Identify One Additional SPM by Subsite of Index HN Cancer

| SPM Site | No. of Patients by Subsite |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All HN Primaries | Oral Cavity | Oropharynx | Larynx | Hypopharynx | |

| All solid tumors | 60 | 44 | 48 | 68 | 33 |

| Lung and bronchus | 133 | 145 | 126 | 107 | 72 |

| HN | 167 | 86 | 119 | 341 | 119 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx | 184 | 95 | 133 | 378 | 125 |

| Oropharynx | 5,464 | 3,663 | 2,809 | 7,576 | 4,032 |

| Larynx | 1,553 | 796 | 1,104 | 3,534 | 1,873 |

| Hypopharynx | 1,805 | 1,145 | 1,088 | 2,681 | 2,141 |

| Esophagus | 702 | 436 | 477 | 1,156 | 193 |

| All non-HNLE sites | 963 | 1063 | 695 | 961 | 721 |

Abbreviations: SPM, second primary malignancy; HN, head and neck; HNLE, head and neck, lung, and esophagus.

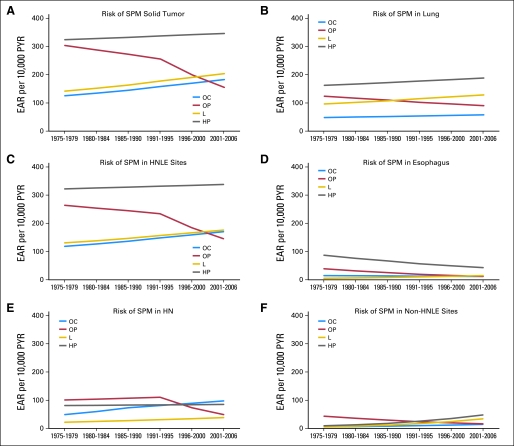

Trends in second primary cancer risk by EAR for each subsite were analyzed by using joinpoint regression (Fig 2). Between 1975 and 2006, the excess burden of SPM was consistently highest for patients with hypopharyngeal primary cancers, and it was lowest for patients with oral cavity and larynx primary cancers. Table 4 shows the corresponding annual percentage change for each HNSCC subsite trend line. Over time, in contrast to the other three subsites, there has been a substantial decline in the risk of SPM in patients with oropharyngeal primary cancers (annual percentage decrease of 1.2 to 7.8%; P = .03 to .26). This corresponds to 10-year decreases in excess SPM risk of 11.3 to 55.6%. In most occurrences, the joinpoint regression model determined that the SPM trend line in oropharyngeal SCC patients changed after 1991. Before the 1990s, oropharynx index cancers carried the second highest excess burden of SPM of any head and neck subsite. Currently, oropharynx index cancers carry the lowest excess burden of SPM.

Fig 2.

Trends (1975-2006) in excess absolute risk (EAR) of second primary malignancy (SPM) by site of index head and neck cancer (HN): (A) second solid tumor; (B) second primary lung cancer; (C) second primary head and neck, lung, or esophagus cancer (HNLE); (D) second primary esophageal cancer; (E) second primary HN; and (F) second primary non-HNLE cancer. PYR, person-years at risk; OC, oral cavity; OP, oropharynx; L, larynx; HP, hypopharynx.

Table 4.

APC Over Time in the Risk of SPM by Head and Neck Subsite

| Subsite by Years and SPM Site | Trend in Excess Absolute Risk |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| APC | 95% CI | P | |

| SPM solid tumor | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-2006 | 1.5 | 0.4 to 2.5 | .02 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-1991 | −1.1 | −4.6 to 2.6 | .17 |

| 1991-2001 | −4.9 | −11.9 to 2.8 | .08 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 1.4 | 0.2 to 2.6 | .04 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | 0.3 | −2.9 to 3.6 | .84 |

| SPM in HNLE | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-2006 | 1.4 | 0.8 to 2.0 | .01 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-1991 | −0.8 | −2.4 to 0.9 | .11 |

| 1991-2001 | −4.6 | −6.3 to −2.9 | .03 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 1.2 | 0.6 to 1.7 | .01 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | 0.2 | −1.5 to 1.9 | .85 |

| SPM in HN | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-1985 | 4.0 | −38.8 to 76.9 | .52 |

| 1985-2001 | 1.8 | −21.9 to 32.7 | .55 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-1991 | 0.6 | −17.1 to 22.0 | .77 |

| 1991-2001 | −7.8 | −40.5 to 42.9 | .26 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 2.1 | 0.8 to 3.4 | .009 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | 0.2 | −2.7 to 3.1 | .88 |

| SPM in lung | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-2006 | 0.7 | −1.7 to 3.1 | .47 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-2006 | −1.2 | −2.2 to −0.2 | .029 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 1.1 | −0.1 to 2.3 | .06 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | 0.6 | −2.6 to 3.9 | .75 |

| SPM in esophagus | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-2006 | −0.8 | −2.9 to 1.4 | .38 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-2006 | −4.1 | −7.9 to −0.1 | .046 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 3.5 | −3.2 to 10.7 | .22 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | −2.6 | −6.7 to 1.7 | .16 |

| SPM in non-HNLE | |||

| OC | |||

| 1975-2006 | 3.6 | −13.0 to 23.3 | .61 |

| OP | |||

| 1975-2006 | −3.7 | −6.8 to −0.4 | .032 |

| L | |||

| 1975-2006 | 6.8 | −16.1 to 35.8 | .50 |

| HP | |||

| 1975-2006 | 6.3 | −3.3 to 16.9 | .16 |

Abbreviations: APC, annual percentage change; SPM, second primary malignancy; OC, oral cavity; OP, oropharynx; L, larynx; HP, hypopharynx; HNLE, head and neck, lung, and esophagus; HN, head and neck.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort study, we report risks of SPM after an index head and neck cancer. The burden of SPM is high in patients with HNSCC, with 168 excess second solid tumors developing per 10,000 PYR. SPM risk was highest for index hypopharyngeal cancers. Lung cancer accounted for the largest proportion of excess second cancer burden and was the most common SPM associated with HNSCC of the larynx or hypopharynx. Second head and neck cancer was the most common SPM associated with an index oral cavity or oropharynx cancer. The most striking observation was that, over 3 decades in the United States, the risk of SPM in patients with oropharyngeal SCC has declined dramatically. Oropharynx was the subsite with second highest SPM risk until the last decade and is now the subsite with lowest SPM risk.

There are several caveats to our data. First, there are limitations to data in the SEER registry. A small percentage of recurrences in adjacent anatomic locations could theoretically be misclassified as SPM. Lung metastases may be misclassified as second primary lung cancers or vice versa. These issues are also inevitable in clinical practice, and we attempted to minimize misclassification in this study with the strict application of modified Warren and Gates criteria for SPM.28,29 Migration of patients out of a SEER geographic registry will lead to underestimation of SPM risk. However, this phenomenon is most common among children and young adults, who make up a small percentage of patients with HNSCC. Finally, SEER data do not record cancer risk factors, such as tobacco use, alcohol use, and HPV status, and we were therefore unable to incorporate these factors into a wider analysis of risk factors for SPM. It is likely that the subsite-specific differences in SPM risk are attributable to differences in attributable cancer risk as a result of exposure to tobacco and alcohol, as has been demonstrated in recent international pooled case-control data.18,20

A final caveat is that the definition of SPM is likely to be refined in the future. Contemporary research into field cancerization has revealed that abnormalities such as TP53 gene mutation, loss of heterozygosity, and high Ki-67 proliferation index are present in histologically normal mucosa adjacent to a head and neck tumor. It is likely that some cancers currently considered second cancers are in fact recurrences within an area of pre-existing genetic field cancerization.5,34 For the purposes of this study, we were necessarily limited to clinical criteria for SPM.

Methodologic strengths of this study include large sample size, near complete follow-up, and high quality control of the SEER program, considered the standard for quality among international cancer registries.29 Risks are calculated relative to large SEER reference cohorts, thus maximizing both internal validity and generalizability of results. Joinpoint regression allowed identification of changes in cancer incidence trends over time, facilitating the identification of recent changes in SPM risk associated with oropharyngeal cancer that would not have been evident with standard linear regression.

Subsite-Specific Risks

Differences in overall SPM risk by index HNSCC subsite were recently described in a pooled analysis of international cancer registry data.11 Several smaller single-institution studies have reported that laryngeal cancer appears most strongly associated with SPMs in the lung, whereas oral cavity cancer is most strongly associated with SPMs in the head and neck.2,13–15,17,35,36 In our study, we have validated these findings and comprehensively defined the risk and distribution of SPMs associated with each of the four major HNSCC subsites.

For patients with index oral cavity or oropharyngeal SCC, there were strongly elevated risk ratios for the development of a head and neck SPM, with SIR values greater than 20. Accordingly, the highest absolute number of excess SPMs was observed in the head and neck. In patients with index laryngeal SCC, the relative risk for a second head and neck cancer (SIR, 5.8) was only slightly higher than for a second primary cancer in the lung (SIR, 4.1). Because of the much higher number of expected lung cancers, the highest absolute number of excess SPMs was observed in the lung. Patients with index hypopharyngeal SCC had relative risks for SPM that were highest of any subsite.

Number needed to observe figures for patients with hypopharyngeal SCC were striking: in 1 year, one of 33 patients will develop a second primary solid cancer as a result of the history of HNSCC; one of 72 will develop a lung cancer; one of 125 will develop an oral cancer; and one of 193 will develop an esophageal cancer. These numbers are presented solely as context for the EAR values and may inform the design of prospective studies of screening in high-risk patients but cannot of themselves prove the efficacy of any screening technique.

Subsite-Specific Trends in the HPV Era

The regression lines of SPM risk over time, as measured by EAR, revealed two patterns. Between 1975 and 2006, the excess absolute risk of SPM has been stable to slightly increasing among patients with index HNSCC of the oral cavity, larynx, and hypopharynx. We attribute these mild increases to three possible causes. First, more sensitive imaging modalities have improved detection of SPM; for example, small, indolent pulmonary lesions may be more commonly identified. Second, improved imaging and biopsy techniques may have allowed correct classification of lesions, previously thought to be metastases, as SPMs. Third, as tobacco use has declined in the United States,37 the tobacco use behaviors of patients with HNSCC and reference patients may have diverged, leading to a declining number of expected tobacco-related cancers in the reference population against which HNSCC patients are compared (the SIR denominator) and, thereby, to a slight increase in SIR and EAR values.

In contrast to the trends in the other subsites, the excess risk of second cancers in patients with an index oropharyngeal SCC has declined dramatically since the early 1990s, with the risk of SPM having now declined to the lowest risk of any head and neck subsite. This finding is consistent with the recent predominance of HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC. Over the past 2 decades, the etiology of oropharynx cancer has shifted from predominantly tobacco and alcohol–related to predominantly oncogenic HPV-related. In Colorado, the percentage of oropharyngeal SCC found to be HPV positive increased from 42% before 1995 to 79% after 1995.38 In Sweden, the HPV-positive proportion of tonsil SCC increased from 23% in the 1970s to 28% in the 1980s, 57% in the 1990s, and 79% in 2000 to 2007.39 In recent data from the University of Michigan, 82% of oropharyngeal tumors between 2002 and 2007 were HPV positive.40

To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive data have been reported on the risk of SPM among HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancers, although Licitra et al41 observed a nonsignificant trend toward lower SPM risk in patients with HPV-positive disease.41 More recently, Ang et al21 have reported a lower rate of second head and neck and lung cancers among patients with HPV-positive tumors.21 Existing data do provide a rationale for hypothesizing that the risk of SPM in patients with HPV-positive SCC would be lower. Patients with HPV-positive disease are more likely to lack systemic exposure to tobacco and alcohol and to be predominantly subjected to local exposure to an oncogenic virus with tropism for oropharyngeal epithelium. Now that the vast majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers are viral in etiology, the risk of SPM has declined to low levels. This explanation will best be validated in prospective or nested case-control studies. We believe that the significantly lower risk of SPM in modern HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC may be a major contributor to the demonstrated superior survival outcomes among patients with HPV-positive disease.40,42,43

In conclusion, SPMs in patients with an index HNSCC are common and represent a significant obstacle to improvements in survival. Multiple investigators have demonstrated that SPMs negatively impact survival in patients with HNSCC.15,44,45 Our findings highlight the broad public health consequences of tobacco use, which not only causes single cancers, but also leads to long-term increased risk of second and multiple primary cancers. These data may impact follow-up surveillance strategies in patients with HNSCC. Patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal SCC may be at lower SPM risk. The hypotheses generated by these data will be helpful in informing future investigations of surveillance strategies in patients with HNSCC.

Appendix

Table A1.

Crude Incidence and Location of SPM by Head and Neck Subsite

| Variable | All Sites |

Subsite |

P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Cavity |

Oropharynx |

Larynx |

Hypopharynx |

||||||||

| No. (N = 75,087) | %(100%) | No. (n = 36,107) | %(48.1%) | No. (n = 8,440) | %(11.2%) | No. (n = 25,624) | %(34.1%) | No. (n = 4,916) | %(6.5%) | ||

| Incidence of SPM | |||||||||||

| Patients with any number of SPMs | 17,441 | 23.2 | 8,294 | 23.0 | 1,674 | 19.8 | 6,594 | 25.7 | 879 | 17.9 | < .001 |

| Patients with 1 SPM | 14,720 | 19.6 | 7,004 | 19.4 | 1,230 | 14.5 | 5,723 | 22.3 | 763 | 15.5 | < .001 |

| Patients with 2 SPMs | 2,103 | 2.8 | 1,071 | 3.0 | 177 | 2.1 | 757 | 3.0 | 98 | 2.0 | < .001 |

| Patients with 3 or more SPMs | 618 | 0.8 | 219 | 0.6 | 267 | 3.1 | 114 | 0.5 | 18 | 0.4 | < .001 |

| Location of SPM | < .001 | ||||||||||

| Head and neck | 3,696 | 17.7 | 2,266 | 27.9 | 484 | 28.8 | 765 | 11.7 | 181 | 20.6 | |

| Oral cavity | 2,135 | 10.2 | 1,369 | 16.8 | 289 | 17.2 | 359 | 5.5 | 118 | 13.4 | |

| Oropharynx | 826 | 3.9 | 459 | 5.6 | 105 | 6.2 | 221 | 3.4 | 41 | 4.7 | |

| Larynx | 422 | 2.0 | 256 | 3.1 | 52 | 3.1 | 102 | 1.6 | 12 | 1.4 | |

| Hypopharynx | 313 | 1.5 | 182 | 2.2 | 38 | 2.2 | 83 | 1.3 | 10 | 1.1 | |

| Lung and bronchus | 5,394 | 25.8 | 2,049 | 25.2 | 529 | 31.5 | 2,487 | 38.0 | 329 | 37.4 | |

| Esophagus | 861 | 4.1 | 433 | 5.3 | 103 | 6.2 | 220 | 3.4 | 105 | 11.9 | |

| All non-HNLE sites | 7,281 | 34.8 | 3,386 | 41.6 | 566 | 33.7 | 3,065 | 46.9 | 264 | 30.0 | |

NOTE. P values represent subsite comparisons on analysis of variance or χ2 tests.

Abbreviations: SPM, second primary malignancy; HNLE, head and neck, lung, and esophagus.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. T32 CA009685.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Luc G.T. Morris, Andrew G. Sikora, Richard B. Hayes, Ian Ganly

Financial support: Luc G.T. Morris

Administrative support: Luc G.T. Morris

Provision of study materials or patients: Luc G.T. Morris

Collection and assembly of data: Luc G.T. Morris

Data analysis and interpretation: Luc G.T. Morris, Richard B. Hayes, Ian Ganly

Manuscript writing: Luc G.T. Morris, Andrew G. Sikora, Snehal G. Patel, Richard B. Hayes, Ian Ganly

Final approval of manuscript: Luc G.T. Morris, Andrew G. Sikora, Snehal G. Patel, Richard B. Hayes, Ian Ganly

REFERENCES

- 1.Vikram B. Changing patterns of failure in advanced head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110:564–565. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800350006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.León X, Quer M, Diez S, et al. Second neoplasm in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1999;21:204–210. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199905)21:3<204::aid-hed4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturgis EM, Miller RH. Second primary malignancies in the head and neck cancer patient. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:946–954. doi: 10.1177/000348949510401206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garavello W, Ciardo A, Spreafico R, et al. Risk factors for distant metastases in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:762–766. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ha PK, Califano JA. The molecular biology of mucosal field cancerization of the head and neck. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:363–369. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::aid-cncr2820060515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boice JD, Jr, Fraumeni JF., Jr Second cancer following cancer of the respiratory system in Connecticut, 1935-1982. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1985;68:83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veli EM, Schatzkin A. Common environmental risk factors. In: Neugut AI, editor. Multiple Primary Cancers. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tepperman BS, Fitzpatrick PJ. Second respiratory and upper digestive tract cancers after oral cancer. Lancet. 1981;2:547–549. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gluckman JL, Crissman JD. Survival rates in 548 patients with multiple neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:71–74. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuang SC, Scelo G, Tonita JM, et al. Risk of second primary cancer among patients with head and neck cancers: A pooled analysis of 13 cancer registries. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2390–2396. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Rubin P, et al. Second malignancies in patients who have head and neck cancer: Incidence, effect on survival and implications based on the RTOG experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:449–456. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vries N, Snow GB. Multiple primary tumours in laryngeal cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 1986;100:915–918. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries N, Van der Waal I, Snow GB. Multiple primary tumours in oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15:85–87. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(86)80015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin K, Patel SG, Chu PY, et al. Second primary malignancy of the aerodigestive tract in patients treated for cancer of the oral cavity and larynx. Head Neck. 2005;27:1042–1048. doi: 10.1002/hed.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennemo E, Zätterström U, Boysen M. Impact of second primary tumors on survival in head and neck cancer: An analysis of 2,063 cases. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1350–1356. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318172ef9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones AS, Morar P, Phillips DE, et al. Second primary tumors in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;75:1343–1353. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950315)75:6<1343::aid-cncr2820750617>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, et al. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:541–550. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubin JH, Purdue M, Kelsey K, et al. Total exposure and exposure rate effects for alcohol and smoking and risk of head and neck cancer: A pooled analysis of case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:937–947. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purdue MP, Hashibe M, Berthiller J, et al. Type of alcoholic beverage and risk of head and neck cancer: A pooled analysis within the INHANCE Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:132–142. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung CH, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer: Its role in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6758–6762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harlan LC, Hankey BF. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end-results program database as a resource for conducting descriptive epidemiologic and clinical studies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2232–2233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.94.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: Selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results— National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:417–435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren S, Gates O. Multiple primary malignant tumors: A survey of the literature and a statistical study. Am J Cancer. 1932;16:1358–1414. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis RE, Ries LA. Methods. In: Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, et al., editors. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoenberg BS, Myers MH. Statistical methods for studying multiple primary malignant neoplasms. Cancer. 1977;40(suppl):1892–1898. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4+<1892::aid-cncr2820400820>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Begg CB, Zhang ZF, Sun M, et al. Methodology for evaluating the incidence of second primary cancers with application to smoking-related cancers from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:653–665. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslow NE, Day NE. Lyon, France: International Association for Research on Cancer; 1987. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research (vol 2): The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies; pp. 69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, et al. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Leemans CR, et al. Second primary tumors and field cancerization in oral and oropharyngeal cancer: Molecular techniques provide new insights and definitions. Head Neck. 2002;24:198–206. doi: 10.1002/hed.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haughey BH, Gates GA, Arfken CL, et al. Meta-analysis of second malignant tumors in head and neck cancer: The case for an endoscopic screening protocol. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:105–112. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto E, Shibuya H, Yoshimura R, et al. Site specific dependency of second primary cancer in early stage head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2007–2014. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CDC grand rounds. Current opportunities in tobacco control. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernster JA, Sciotto CG, O'Brien MM, et al. Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:2115–2128. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31813e5fbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Näsman A, Attner P, Hammarstedt L, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive tonsillar carcinoma in Stockholm, Sweden: An epidemic of viral-induced carcinoma? Int J Cancer. 2009;125:362–366. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. Tobacco use in human papillomavirus-positive advanced oropharynx cancer patients related to increased risk of distant metastases and tumor recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1226–1235. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Licitra L, Perrone F, Bossi P, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus affects prognosis in patients with surgically treated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5630–5636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindquist D, Romanitan M, Hammarstedt L, et al. Human papillomavirus is a favourable prognostic factor in tonsillar cancer and its oncogenic role is supported by the expression of E6 and E7. Mol Oncol. 2007;1:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen MC, Huang WC, Chan CH, et al. Impact of second primary esophageal or lung cancer on survival of patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erkal HS, Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, et al. Synchronous and metachronous squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck mucosal sites. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1358–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]