Abstract

Objective

To describe key determinants for residents’ selection of a new community-based, interprofessional site for their family medicine training, and to evaluate residents’ satisfaction with their programs.

Design

Combined qualitative and quantitative methods using in-depth interviews and a survey.

Setting

McMaster University, including the new site of the Centre for Family Medicine in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ont, and a long-established site in Hamilton, Ont.

Participants

Eleven first-year and second-year family medicine residents from the Kitchener-Waterloo site participated in in-depth interviews. Forty-four first-year and second-year family medicine residents completed the survey, 22 in Kitchener-Waterloo and 22 in Hamilton.

Methods

Kitchener-Waterloo residents participated in in-depth interviews during their residency programs in 2008 to 2009 using a semistructured format to explore their choice of site and the effect of an interprofessional environment on their education. Common themes were established using qualitative analysis techniques; based on these themes, a survey was developed and distributed to residents from both sites to further explore factors influencing site selection, satisfaction, and effects of interprofessional education.

Main findings

Residents identified several reasons for selecting a new community-based, interprofessional family medicine residency program. Reasons included preference for the location and opportunities to learn in an interprofessional teaching environment. A less hierarchical structure and greater opportunities for one-on-one teaching also influenced their choices. Perception of poor communication from the well established site was identified as a challenge. Residents at both sites indicated similarly high levels of program satisfaction.

Conclusion

Residents selected the new community-based family medicine site for reasons of geographic location and the potential for clinical learning experiences and interprofessional education. High program satisfaction was achieved at both the new and well established sites. Family medicine residency programs developing community-based networks might consider and encourage the positive influence of interprofessional care and education. Good communication between distributed sites remains a challenge.

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire les facteurs clés qui amènent les résidents à choisir un nouveau site interdisciplinaire en milieu communautaire pour leur formation en médecine familiale et évaluer leur niveau de satisfaction à l’égard de leur programme.

Type d’étude

Méthodes à la fois qualitative et quantitative au moyen d’entrevues en profondeur et d’une enquête.

Contexte

L’Université McMaster, incluant le nouveau Centre de médecine familiale à Kitchener-Waterloo (Ont.), et un site établi depuis longtemps à Hamilton (Ont.).

Participants

Onze résidents de première et deuxième années du programme de médecine familiale du site de Kitchener-Waterloo ont participé aux entrevues en profondeur. Quarante-quatre résidents en médecine familiale des première et deuxième années ont répondu à l’enquête, 22 à Kitchener-Waterloo et 22 à Hamilton.

Méthodes

Les résidents de Kitchener-Waterloo ont participé aux entrevues en profondeur durant leur programme de résidence entre 2008 et 2009 à l’aide d’une version semi-structurée permettant d’établir leur choix de site et l’effet d’un milieu interdisciplinaire sur leur formation. Des techniques d’analyse qualitative ont servi à identifier les thèmes communs; à partir de ces thèmes, on a développé une enquête qui a été soumise aux résidents des deux sites pour mieux établir les facteurs qui influent sur leur choix de site, leur satisfaction et les effets d’une formation interdisciplinaire.

Principales observations

Les résidents ont cerné plusieurs raisons pour choisir un nouveau programme interdisciplinaire de résidence en médecine familiale en milieu communautaire. Ces raisons comprenaient une préférence pour l’endroit et la possibilité d‘apprendre dans un milieu d’enseignement interdisciplinaire. Une structure moins hiérarchique et la possibilité d’un enseignement individualisé avaient aussi influencé leur choix. La perception d’une faiblesse dans les communications au site déjà bien établi a été citée comme une difficulté. Les résidents ont rapporté des niveaux de satisfaction élevés relativement à leur programme, aux 2 endroits.

Conclusion

Les résidents choisissaient le nouveau site de médecine familiale en milieu communautaire en raison du lieu géographique et pour profiter d’un apprentissage clinique et d’une formation interdisciplinaire. Des niveaux élevés de satisfaction étaient observés au nouveau site comme à l’ancien. Les programmes de résidence en médecine familiale qui développent des réseaux en milieu communautaire devraient tenir compte des effets favorables des soins et de la formation interdisciplinaires, et en faire la promotion. Une communication adéquate entre les sites demeure toutefois un défi.

The Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, has developed a distributed network for its residency program in South-Central Ontario. The first major urban site developed outside of Hamilton is located in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ont, where residents began participating in the full 2-year curriculum beginning in 2005. The local program has a separate Canadian Resident Matching Service stream established, and its first graduates completed their entire residency in the Kitchener-Waterloo area in 2007.

The principle setting for the program in Kitchener-Waterloo is the Centre for Family Medicine, a family health team developed as the regional clinical teaching site for a new health sciences campus, which includes a pharmacy school, a regional medical school, and an optometry training clinic. When the Kitchener-Waterloo program was established, the provincial Ministry of Health had designated the area as underserviced by family physicians.

There has been a shift in training to community-based centres, highly valued by learners, in many programs.1 Training in distributed sites often links communities, governments, and universities in an effort to assist with recruitment and human resource distribution to help alleviate the shortage of family physicians.2

Family practice in Canada has been developing an interprofessional component also with the goal of alleviating the family physician shortage. The Kitchener-Waterloo site’s family health team was established as one of Ontario’s first interprofessional care institutions in 2005.

A review of the literature revealed no studies examining the key determinants of location choices of and satisfaction with family medicine residency training sites featuring an interprofessional component.

The purpose of this study was to determine the key factors affecting family medicine residents’ choice of a distributed program in a new location and their perceptions of interprofessional education.

METHODS

A mixed-method approach was used. Qualitative in-depth interviews initially explored the themes surrounding residents’ experiences with the new distributed program and informed the development of a quantitative survey that further garnered data on site selection, program satisfaction, and interprofessional education.

In-depth interviews

In 2008 to 2009, in-depth interviews were conducted with 11 first-year and second-year family medicine residents at the Kitchener-Waterloo site by one of the researchers (M.A.) who was not a resident preceptor. Ethics approval was obtained from McMaster University and informed consent was obtained from participants. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached through an iterative process by 2 of the researchers involving a minimum of 3 iterations. Interviews of 30 to 60 minutes’ duration were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. A semistructured interview format was used, with thematic analysis conducted independently by 2 of the researchers after each interview, followed by comparison and corroboration. Immersion and crystallization techniques were used.

Survey

Based on themes obtained from the interviews, a quantitative survey was developed with 3 sections: reasons for site selection, program satisfaction, and exposure to interprofessional collaboration. Ethics approval was obtained from McMaster University and the survey was distributed to McMaster family medicine residents at 2 sites, Kitchener-Waterloo and Hamilton, during 2008 to 2009. All 22 residents in Kitchener-Waterloo completed the survey and an equal number of participants was selected at random in Hamilton. Participants received an honorarium of a small-value gift card. Completion of the survey was anonymous. The survey included open-ended and closed-ended questions with responses measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

Fischer exact tests were used owing to the small sample size, with an α value of .05 to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

The in-depth interviews revealed 4 main themes: location and community; interprofessional environment; less hierarchical structure or hands-on teaching; and resident satisfaction or poor communication with the central site. The survey was designed to reflect these themes. All 22 residents of the Kitchener-Waterloo site completed the survey for a response rate of 100%. Twenty-two residents from the Hamilton site chosen at random completed the survey as a comparison group. Combined results of the interviews and survey are explained below.

Location and community

During the in-depth interviews, almost all the residents identified location and community as important factors in choosing the Kitchener-Waterloo site:

“This is my home town.”

“I had done my clerkship here in Kitchener-Waterloo ... I really like the city.”

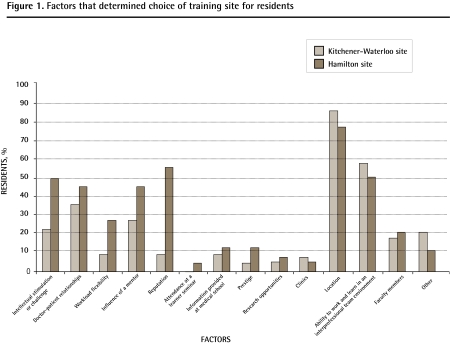

Among the factors determining choice of a residency program site (Figure 1), the following 6 factors were the most frequently identified by residents in the survey: location, intellectual stimulation, ability to work in an interprofessional team environment, patient-doctor relationships, reputation, and influence of a mentor.

Figure 1.

Factors that determined choice of training site for residents

Interprofessional environment

Most of the Kitchener-Waterloo residents who were interviewed expressed that the interprofessional environment was a positive factor in their program:

“I just feel like I’ve learned more. I really do. I believe we learn more here than other people do.”

“Certainly at the Kitchener site, you don’t go anywhere without bumping into interprofessional care.”

The ability to work in an interprofessional team was identified as an influencing factor by 59.1% of the Kitchener-Waterloo residents, making it the second most frequently identified factor in choice of residency program selection.

Similar percentages of Kitchener-Waterloo and Hamilton residents had completed a horizontal elective with an interprofessional provider (63.6% Hamilton site residents, 72.7% Kitchener-Waterloo site residents). Approximately half of the residents at each site had had 11 or more interactions with interprofessional providers (45.5% Hamilton, 50.0% Kitchener-Waterloo).

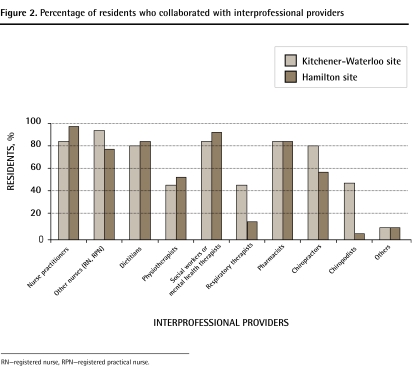

Similar percentages (Figure 2) of the Kitchener-Waterloo and Hamilton residents indicated they had collaborated with various interprofessional providers, including nurse practitioners, nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists, social workers or mental health therapists, and pharmacists. There were substantially more exposures to chiropractors, chiropodists, and respiratory therapists at the Kitchener-Waterloo site, reflecting differences in the team compositions.

Figure 2.

Percentage of residents who collaborated with interprofessional providers

RN—registered nurse, RPN—registered practical nurse.

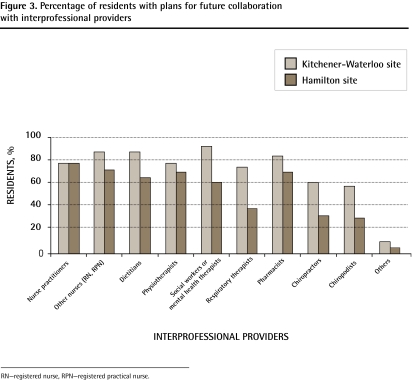

Residents were also surveyed about their future plans to collaborate with the above-mentioned interprofessional providers (Figure 3). Generally, Kitchener-Waterloo residents planned future collaboration more than Hamilton residents.

Figure 3.

Percentage of residents with plans for future collaboration with interprofessional providers

RN—registered nurse, RPN—registered practical nurse.

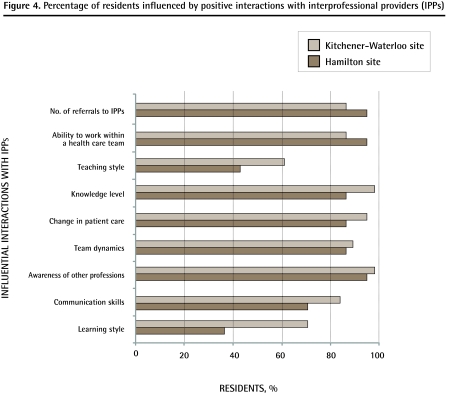

The influence of interactions with interprofessional providers on learning style, communication skills, awareness of other professionals, team dynamics, change in patient care, knowledge level, teaching style, ability to work within a health care team, and number of referrals to interprofessional providers was also determined through the survey. There were no significant differences noted between the 2 groups of residents in any of these variables. Both groups of residents reported positive interactions with interprofessional providers (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of residents influenced by positive interactions with interprofessional providers (IPPs)

Less hierarchical structure and hands-on teaching

Almost all interviewed Kitchener-Waterloo residents stated that the less hierarchical structure, one-on-one teaching, and excellent teaching opportunities in a community-based practice were important factors in their programs:

“I have way more face time with preceptors.”

“I get more respect in the hospitals and you get to do a lot more.”

“I think the quality of learning is much better here. I like the more individual attention.”

Poor communication with the central site

Almost all the interviewed Kitchener-Waterloo residents voiced frustrations with communication from the central site in Hamilton to their new site.

“You don’t feel as involved with the [wider] program .... There’s a separation.”

“Hamilton has some communication problems with their peripheral sites ... that is reflected in us not knowing ... or finding out about things too late and such.”

“We still had weeks of horrible communication in which the residents actually just got left out altogether .... They just cancelled the videoconferencing. It was purely bad communication from Hamilton.”

Residents were surveyed on whether experiences were available, whether the experiences prepared them for future practice, and whether they believed experiences should be mandatory for the following areas: collaborative care; communication skills; computer skills or clinical information retrieval; critical appraisal skills; end-of-life issues; ethics and professionalism; evidence-based medicine; office procedures; hands-on research experience; hands-on teaching experience; working with a health care team; and working with an interdisciplinary team.

There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 sites for any of these areas except for the availability of opportunities to learn critical appraisal skills (Kitchener-Waterloo 77.3%, Hamilton 100%, P = .05) and end-of-life preparedness (Kitchener-Waterloo 36.4%, Hamilton 77.3%, P = .01). There was no significant difference in critical appraisal skills preparedness (Kitchener-Waterloo 86.4%, Hamilton 81.8%), and there was no significant difference in availability of end-of-life experiences (Kitchener-Waterloo 77.3%, Hamilton 90.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of residents who believed the following to be true: Experience in various areas of practice was available; experience in various areas of practice prepared them for future practice; and experiences in various area of practice should be mandatory.

| AREAS OF PRACTICE |

EXPERIENCE IN AREA OF PRACTICE WAS AVAILABLE |

EXPERIENCE IN AREA OF PRACTICE PREPARED RESIDENTS FOR FUTURE PRACTICE |

EXPERIENCE IN AREA OF PRACTICE SHOULD BE MANDATORY |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESIDENTS AT KW SITE, % | RESIDENTS AT HAMILTON SITE, % | P VALUE | RESIDENTS AT KW SITE, % | RESIDENTS AT HAMILTON SITE, % | P VALUE | RESIDENTS AT KW SITE, % | RESIDENTS AT HAMILTON SITE, % | P VALUE | |

| Collaborative care | 95.5 | 100 | NS | 86.4 | 90.9 | NS | 77.3 | 86.4 | NS |

| Communication skills | 95.5 | 95.5 | NS | 100 | 90.9 | NS | 81.8 | 77.3 | NS |

| Information technology skills (computers, etc) | 68.2 | 81.8 | NS | 81.8 | 72.7 | NS | 59.1 | 72.7 | NS |

| Critical appraisal | 77.3 | 100 | .048 | 86.4 | 81.8 | NS | 81.8 | 81.8 | NS |

| End-of-life issues | 77.3 | 90.9 | NS | 36.4 | 77.3 | .013 | 86.4 | 81.8 | NS |

| Ethics and professionalism | 90.9 | 100 | NS | 81.8 | 90.9 | NS | 81.8 | 77.3 | NS |

| Evidence-based medicine | 95.5 | 100 | NS | 90.9 | 81.8 | NS | 81.8 | 81.8 | NS |

| Office procedures | 86.4 | 72.7 | NS | 50.0 | 36.4 | NS | 63.6 | 72.7 | NS |

| Hands-on research | 81.8 | 86.4 | NS | 50.0 | 36.4 | NS | 18.2 | 36.4 | NS |

| Hands-on teaching | 72.7 | 95.5 | .09 | 72.7 | 54.5 | NS | 45.5 | 50.0 | NS |

| Working with health care team | 95.5 | 100 | NS | 100 | 95.5 | NS | 86.4 | 86.4 | NS |

| Interdisciplinary team | 100 | 100 | NS | 86.4 | 95.5 | NS | 86.4 | 86.4 | NS |

KW—Kitchener-Waterloo, NS—not significant.

Most of the residents in both sites thought their residency training was preparing them well for their future family medicine practice (Kitchener-Waterloo 95.5%, Hamilton 86.4%).

Overall, 86.4% of both groups of residents were satisfied or very satisfied with their residency programs.

DISCUSSION

This study has identified several factors that influenced residents’ selection of a new community-based, interprofessional family medicine residency program. Factors included location in a known community, an interprofessional learning environment, a less hierarchical structure, opportunities for more one-on-one teaching, and the potential for excellent teaching experiences.

Community-based and academic sites have been noted to have some differences that might be seen as complementary to each other in family medicine clerkship, as most medical schools use community preceptors as clinical teachers.3 Community-based training for residents has been highly valued by residents and preceptors.1

Family medicine residency programs across Canada are developing networks involving many communities previously not involved in training residents. Training in new sites often links communities, governments, and universities in an effort to assist with recruitment and human resource distribution to help with the shortage of family physicians.2 This is not without challenges; the University of Calgary, for example, was unsuccessful in recruiting family physician graduates to rural areas.4

Residents valued the ability to learn in an interprofessional environment. Clinical exposure to other health care professionals facilitated their education. Barr stated that there are 4 foci for interprofessional education (IPE): preparing for collaborative practice, learning to work in teams, developing services to improve care, and improving quality of life in communities.5 Family medicine is well suited for IPE, as these foci occur naturally in practice. Poorly planned and delivered IPE can reinforce professional differences, so its use needs to reflect local needs, opportunities, and resources.6 There are few reports of controlled studies of IPE in primary care, but the setting can contribute to fostering positive learner attitudes for interprofessional care and development of team skills.7 In a publication addressing IPE, Barker and Oandasan8 caution that faculty members need to be involved in interprofessional care and understand IPE. Residents might receive “mixed messages” otherwise.8

Intentional team training and development can lead to the expression of a high-functioning interprofessional team.9 Oandasan and Reeves10 state that if the objective is to teach collaborative competencies, then the content should be focused on enhancing interprofessional knowledge, skills, and attitudes in residency education.

Perceived poor communication from the well established central site to the new site was identified as a challenge. Residents in both sites indicated similarly high levels of program satisfaction including with the teaching quality by family physicians and other health care professionals. The Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University has acknowledged the challenge of communication and has demonstrated support by a number of measures, including improved videoconferencing links, strengthened administration, and increased local autonomy.

A future area of study might be to explore resident training site selection, satisfaction, and burnout. Recruitment of family physicians to rural and traditionally non-academic communities might depend on addressing experiences that deter family medicine residents from these sites while enhancing training in areas that are satisfying. For example, rigorous training in family medicine with hands-on procedural opportunities and breadth of experiences and care has been associated with early career satisfaction in family medicine.11 It might be important for recruitment and human resource planning in family medicine to provide strategies to reduce stress and burnout in family physicians during residency training. A substantial number of residents have noted being stressed; in one study, 22% of residents would not pursue medicine again if given the opportunity to relive their career.12 Lee et al reported high stress in 42.5% of family physicians surveyed.13 They also suggested proactive planning as a strategy to reduce burnout.14 Satisfaction with training for residents and medical students has been highly associated with the learning environment established.15 Studies that explore these themes might assist family medicine residency program directors with addressing potential stress and burnout in training sites while promoting career satisfaction.

Conclusion

This qualitative and quantitative study found that residents select a new community-based family medicine site for reasons that include geographic location and the potential for clinical experiences. Interprofessional education and care were also highly valued.

Program satisfaction in a new site was high and similar to that in a well established site. High resident satisfaction might be a factor in reducing stress and burnout early in physicians’ careers. A less hierarchical structure, opportunities for one-on-one teaching, and excellence in teaching were identified as important factors influencing preference for a community-based program.

Family medicine residency programs developing community-based networks might consider and encourage the positive influence of interprofessional care and education within community settings.

Good communication between central and distributed sites is a challenge that needs to be addressed by the wider program. Intentional support can be provided by specific measures such as use of technology and increased local autonomy.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Community-based training for residents has been highly valued by residents and preceptors.

The goal of this study was to determine the key factors affecting family medicine residents’ choice of a distributed program in a new location and their perceptions of interprofessional education.

Residents identified the following 6 factors most frequently when determining choice of a residency program site: location, intellectual stimulation, ability to work in an interprofessional team environment, patient-doctor relationships, reputation, and influence of a mentor.

Family medicine residency programs developing community-based networks should consider and encourage the positive influence of interprofessional care and education.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Résidents et moniteurs appréciaient hautement que la formation des résidents se fasse en milieu communautaire.

Cette étude avait pour but de déterminer les facteurs clés qui influencent le choix que font les résidents en médecine familiale d’un programme dispensé dans un nouvel endroit et leur perception d’une formation interdisciplinaire.

Les résidents ont observé que les 6 facteurs les plus souvent invoqués au moment de choisir un programme de résidence sont : l’endroit, la stimulation intellectuelle, la capacité de travailler au sein d’une équipe interdisciplinaire, les relations médecin-patient, la réputation et l’influence d’un conseiller.

Les programmes de résidence en médecine familiale qui développent des réseaux en milieu communautaire devraient tenir compte des effets favorables des soins et de la formation interdisciplinaires et en faire la promotion.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Dr Joseph Lee conceived and planned the study and its ethics submission, conducted the research for the study, participated in the thematic development and interpretive analysis, and developed the survey. Ms Alfieri conducted the qualitative interviews, developed the research protocol, prepared ethics submission, participated in the thematic development and interpretive analysis, and developed the survey. Dr Patel participated in the literature search, the quantitative analysis, and the discussion and conclusions. Dr Linda Lee provided advice and guidance on the qualitative and quantitative research protocol, prepared ethics submission, and provided commentary and suggestions on the findings, discussion, and conclusions.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Parenti CM, Moldow CF. Training internal medicine residents in the community: the Minnesota experience. Acad Med. 1995;70(5):366–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaytors RG, Spooner GR. Training for rural family medicine: a cooperative venture of government, university and community in Alberta. Acad Med. 1998;73(7):739–42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney PA, Eliassen MS, Pipas CF, Genereaux SH, Nierenberg DW. Ambulatory care education: how do academic medical centres, affiliated residency teaching sites, and community-based practices compare? Acad Med. 2004;79(1):69–77. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200401000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu DJ, Hakes J, Bai M, Tolhurst H, Dickinson JA. Rural intentions. Factors affecting the career choices of family medicine graduates. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1016-7.e1–5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/cgi/reprint/54/7/1016. Accessed 2011 Feb 10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr H. Interprofessional education: the fourth focus. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(Suppl 2):40–50. doi: 10.1080/13561820701515335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priest H, Sawyer A, Roberts P, Rhodes S. A survey of interprofessional education in communication skills in health care programmes in the UK. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(3):236–50. doi: 10.1080/13561820500053447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman MT, Roberts K, Wulff D, van Zyl R, Newton K. Interprofessional ambulatory primary care practice-based educational program. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(1):69–84. doi: 10.1080/13561820701714763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker KK, Oandasan I. Interprofessional care review with medical residents: lessons learned, tensions aired—a pilot study. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(3):207–14. doi: 10.1080/13561820500138693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashman S, Reidy P, Cody K, Lemay C. Developing and measuring progress toward collaborative, integrated, interdisciplinary health care teams. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(2):183–96. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001686936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part I: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):21–38. doi: 10.1080/13561820500083550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young R, Webb A, Lackan N, Marchand L. Family medicine residency educational characteristics and career satisfaction in recent graduates. Fam Med. 2008;40(7):484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: a survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee FJ, Stewart M, Brown JB. Stress, burnout, and strategies for reducing them. What’s the situation among Canadian family physicians? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:234-5.e1–5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/cgi/reprint/54/2/234. Accessed 2011 Feb 10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee FJ, Brown JB, Stewart M. Exploring family physician stress. Helpful strategies. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:288-9.e1–6. Available from: www.cfp.ca/cgi/reprint/55/3/288. Accessed 2011 Feb 10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon GW, Keitz SA, Holland GJ, Chang BK, Byrne JM, Tomolo A, et al. Factors determining medical students’ and residents’ satisfaction during a VA-based training: findings from the VA Learners’ Perceptions Survey. Acad Med. 2008;83(6):611–20. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181722e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]