Abstract

The processes that occur with normal sternal healing and potential complications related to median sternotomy are of particular interest to physical therapists. The premise of patients following sternal precautions (SP) or specific activity restrictions is the belief that avoiding certain movements will reduce risk of sternal complications. However, current research has identified that many patients remain functionally impaired long after cardiothoracic surgery. It is possible that some SP may contribute to such functional impairments. Currently, SP have several limitations including that they: (1) have no universally accepted definition, (2) are often based on anecdotal/expert opinion or at best supported by indirect evidence, (3) are mostly applied uniformly for all patients without regard to individual differences, and (4) may be overly restrictive and therefore impede ideal recovery. The purpose of this article is to present an overview of current research and commentary on median sternotomy procedures and activity restrictions. We propose that the optimal degree and duration of SP should be based on an individual patient's characteristics (eg, risk factors, comorbidities, previous activity level) that would enable physical activity to be targeted to particular limitations rather than restricting specific functional tasks and physical activity. Such patient-specific SP focusing on function may be more likely to facilitate recovery after median sternotomy and less likely to impede it.

Key Words: median sternotomy, sternal precautions, physical therapy, exercise protocols

INTRODUCTION

Sternal precautions (SP) are almost universally given to patients following median sternotomy surgeries. However, in clinical practice, SP most commonly represent a wide variety of functional restrictions. In fact, the word ‘precautions’ should probably be replaced by the word ‘restrictions’ since this is what many physical therapists have encountered in clinical practice over the years. Restrictions in shoulder range of motion, lifting, reaching, dressing, exercise, driving, and a variety of other tasks have been reported. However, the exact origin of such restrictions is difficult to find. Furthermore, there appears to be no consistency in the type or duration of restriction.

The purpose of this paper is to review the available research related to the median sternotomy procedure and physical activity. We begin with a historical perspective of physical activity after myocardial infarction (MI) and a brief overview of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. We review the literature regarding (1) complications after cardiac surgery and median sternotomy, (2) symptoms and functional status after cardiac surgery, and (3) the changes in pulmonary function and thoracic motion after cardiac surgery. Finally, we propose an algorithm highlighting the role that appropriately prescribed exercise and functional training, based on specific patient characteristics and limitations, may have in improving outcomes after a median sternotomy. Such patient specific precautions, rather than restrictions, which focus on function, may be more likely to facilitate recovery after median sternotomy and less likely to impede it.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The attitude regarding physical activity following the onset of symptomatic coronary artery disease has undergone substantial change in the past two centuries. Prior to 1876, many practitioners favored moderate activity for patients experiencing angina pectoris and with what was later recognized as MI.1 This position was expressed by Austin Flint in 1886: “Patients exchanging habits of activity for complete rest are likely to become rapidly worse.”2 Near the turn of the 19th century, however, physicians became more conservative following observations linking early activity to sudden death in several patients with rheumatic fever.3 Early studies dealing with MI and with ventricular aneurysm development during acute MI recovery seemed to favor a more cautious approach to physical rehabilitation.4,5

A study supporting the prescription of physical activity after MI appeared in 1944. Levine6 found prolonged immobility contributed to 11 negative sequelae ranging from bone demineralization to venous thrombosis. He theorized that the sitting position was beneficial because it promoted peripheral venous pooling and decreased venous return thereby reducing the work of the heart. Patients were permitted to sit in a chair for one to 2 hours beginning the first post-MI day. This procedure became known as the “armchair treatment of coronary thrombosis.”7 Subsequent early studies supported this rehabilitation approach.8,9 Other research followed demonstrating both the physiological and psychological benefits of early exercise participation.10–13

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery

During the 1960s, CABG surgery was introduced as a surgical adjunct to the medical treatment of coronary heart disease.14 Acceptance of this procedure was almost immediate; in 1968 René Favaloro and his Cleveland Clinic colleagues performed 171 CABG operations.15 By 1979, over 100,000 CABG surgeries were documented in America at an average cost to patients of $5,000.16 Not surprisingly, both frequency and expense mushroomed by 2006. A total of 448,000 CABG surgeries were performed that year with procedures ranging from $50,000 to $100,000 per patient.17 Despite the cost involved, it appears CABG surgery will continue as a practical option for coronary heart disease treatment until a viable, nonoperative substitute is found.

As the name implies, CABG surgical technique involves locating and ‘bypassing’ occluded coronary arteries. Often a section from the saphenous vein is selected as the conduit of choice; one end of the vessel is affixed to the aorta while the other end is anastomosed to the blocked coronary artery distal to the occlusion. Arterial conduits are often used as well. A partial list of these vessels includes the internal thoracic (aka internal mammary), radial, subscapular, inferior epigastric, and right gastroepiglotic arteries.18 Historically, all CABG surgeries were performed via a median sternotomy.

With the advent of CABG surgery, a unique group of patients was added to those traditionally involved in cardiac rehabilitation. First, since CABG surgery improves coronary blood flow reducing anginal symptoms, these patients become excellent candidates for more aggressive therapy than their post-MI contemporaries.19 Second, since surgical exposure of the heart is often accomplished via median sternotomy, considerable strain is placed on the anatomy of the chest, back, shoulders, and neck as sternal halves are retracted. Thus, it is not uncommon for patients following CABG surgery to manifest with a variety of musculoskeletal and neurological complaints from the procedure.20 Lastly, surgical site infection involving soft and bony tissues always exists as a possible threat. Indeed, early CABG surgeries were plagued with high infection rates - sometimes resulting in sternectomy or death. Sternal infections and dehiscence at that time were reported in 0.5% to 8.4% of cases with mortality running between 14% and 50% when infection was present.21

STERNAL PRECAUTIONS–CURRENT STATUS

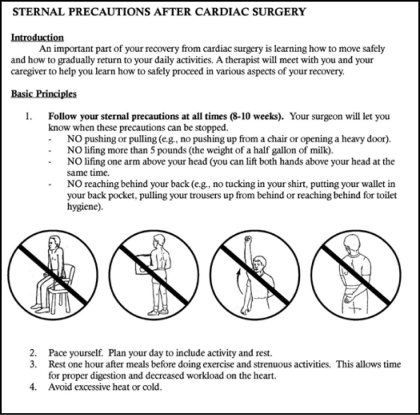

The exact genesis of SP is unknown. However, it is likely that initial concerns regarding sternal infection heightened topic awareness. Add to this the idea that sternum healing might be compromised by certain upper extremity movements and the ‘precaution’ (or really ‘restriction’) stage was set. Although impaired, sternal healing had never been proven empirically, nurses and therapists began presenting patients with a list of proscribed postsurgical movements and activities (Figure 1). Such lists often warned against arm movements above shoulder level (90° of flexion/abduction) and scapular adduction. Other precautions included not lifting more than 5 to 10 pounds, avoiding weight-bearing through the upper extremity (ie, using arm rests to stand), and avoiding unilateral reaching posteriorly (ie, providing support while sitting).

Figure 1.

Example of a sternal precautions sheet presented to patients following CABG surgery prior to hospital discharge.97

Over time, SP became synonymous with responsible patient care. A plethora of protocols subsequently emerged, often with conflicting advice. Table 1 is illustrative of this point. Note the absence of agreement between 3 health care agencies (all residing in the same state) on shoulder movement, lifting, and reaching. OhioHealth limits shoulder movement to 90° while the Cleveland Clinic approves movement above shoulder level. The Ohio State Medical Center limits lifting to 10 pounds while the Cleveland Clinic doubles this amount. Also confusing is OhioHealth's warning about lifting with “your affected arm” since CABG surgery is performed on the chest. Moreover, both Ohio-Health and The Ohio State Medical Center prohibit reaching backward while the Cleveland Clinic is without comment on the matter. Such lack of consensus pertaining to SP not infrequently leads to contentious interactions between surgeons, nurses, and rehabilitation team members.

Table 1.

Comparison of Select Sternal Precautions by Health Care Providers

| Activity | OhioHealth1 | The Ohio State Medical Center2 | Cleveland Clinic3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder Movement | Do not raise your elbows higher than your shoulders | You may move your arms within a pain free range | It is okay to perform activities above shoulder level |

| Lifting | Do not lift greater than 5 to 10 pounds with your affected arm (for 4 weeks) | Do not lift more than 10 pounds for the 6 weeks after your surgery | Do not lift objects greater than 20 pounds for first 6–8 weeks following surgery |

| Reaching | Do not reach behind you when dressing your upper body | Avoid reaching backwards | Not mentioned |

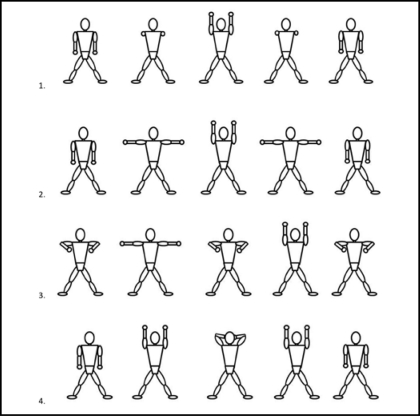

An almost paradoxical stance regarding SP and upper extremity exercise was recently reported by therapists at one Midwestern hospital.22 The very movements typically avoided by most therapists are stressed as important at this facility (Figure 2). Beginning postoperative day one, patients perform active shoulder flexion, shoulder abduction, and scapular adduction exercises. Arm movements are to be performed slowly, are to be free of pain, and should produce limited excursion of sternal halves. Experience-to-date reveals no negative physical therapy outcomes and the protocol, which also includes other exercises, is now accepted as a “standing order” approved by all of the hospitals’ cardiothoracic surgeons.22

Figure 2.

Inpatient CABG exercise regimen showing often contraindicated upper extremity movements. Redrawn from handout obtained from Mary Greeley Medical Center, Ames, Iowa; 2004.22

Although the SP employed by the above Midwestern hospital appear to be uncommon, there appears to be a set of SP that are more commonly prescribed by cardiothoracic surgeons, believed to be important by physical therapists, and observed to be employed in health care facilities by physical therapists.23 A recent survey sent to 1000 US cardiothoracic surgeons and over 600 APTA Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Section members provided information about 28 possible SP. Although there was a poor response rate (10% and 12.5%, respectively), some valuable information was gained.23 Table 2 lists the top 5 SP cardiothoracic surgeons provided to patients after a median sternotomy. Table 2 also lists the top 5 SP that physical therapists believed most important for patients after a median sternotomy as well as the top 5 SP observed by physical therapists in facilities where they worked. Although there are differences between cardiothoracic surgeons and physical therapists, the similarities, particularly regarding lifting, were surprising.23

Table 2.

The Top 5 Sternal Precautions Reported by Cardio-thoracic Surgeons, Physical Therapists, and Those Observed by Physical Therapists in the Facilities Where They Work

|

|

|

Clearly the final chapter concerning SP has yet to be written. Until further evidence is available, perhaps the American College of Sports Medicine provides a voice of reason in the SP debate. The College's recommendations for safe post-CABG exercise are as follow:

For 5 to 8 weeks after cardiothoracic surgery, lifting with the upper extremities should be restricted to 5 to 8 pounds (2.27-3.63 kg). Range of motion (ROM) exercises and lifting 1 to 3 pounds (0.45-1.36 kg) with the arms is permissible if there is no evidence of sternal instability, as detected by movement in the sternum, pain, cracking, or popping. Patients should be advised to limit ROM within the onset of feelings of pulling on the incision or mild pain.24

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Median Sternotomy Complications

Of particular relevance to SP are the processes that occur during normal sternal healing and potential complications related to median sternotomy (Table 3). Sternal wound healing complications can range from superficial skin infections and integumentary dehiscence to sternal instability and mediastinitis.24 Sternal instability is defined as nonphysiologic or abnormal motion of the sternum after either bone fracture or disruption of the wires reuniting the surgically divided sternum. Sternal instability has been shown to be highly associated with the development of mediastinitis and sternal approximation is important for prevention of it.25,26 Mediastinitis involves purulent deep sternal wound infection requiring extensive debridement and drainage. Although the incidence of these more serious sternal complications is relatively low (0.4 to 8%), they are associated with a significant mortality rate (14%-47%). Additionally, the 4-year survival rate of patients with sternal instability and or mediastinitis is 65% versus 89% for those without sternal complications.27–34 Olbrecht and colleagues35 found that prognosis for patients with noninfectious sternal dehiscence was better than for those with infection. Most sternal wound complications (66%) are identified after hospital discharge.31

Table 3.

Complications Associated with Cardiac Surgery via Median Sternotomy

|

Sternal instability can be described acutely as sternal dehiscence/disruption or chronically (> 6 months postoperatively) as sternal nonunion. Sternal separation can take place along the entire sternum or a limited portion, usually the caudal end.25,26 This abnormality in turn can result in sternal clicking, excessive sternal movement, pain, and difficulty performing functional tasks.25 El-Ansary and colleagues25,36 recently developed a 5-point scale for evaluating the severity of sternal instability anchored with a clinically stable sternum/no detectable motion (0) and complete instability >1–1.5 cm (4).

Previous research investigations have identified many of the risk factors associated with median sternotomy complications. Table 4 outlines primary risk factors (identified by multiple research studies) and secondary risk factors (identified by 1–2 research studies) for sternal wound complications.24,27–29,32,34,35,37–44 Obesity or high body mass index is a well-known risk factor for a variety of surgical complications including sternal healing problems.24,34,37–39,42,43 Comorbidities that are highly associated with sternal wound complications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus.24,27,32,35,41,44 In addition, complications with chest surgical wound healing may be exacerbated by tissue ischemia of the anterior chest wall and greater risk of infection exists with harvesting of the internal mammary artery, particularly when it is done bilaterally.29,32,39,41,42,45,46 Recent studies have also identified rethoracotomy (re-entry through the previous median sternotomy incision) and greater blood loss/number of transfused units of blood postsurgically as factors associated with sternal complications.24,29,32,38,41,43,44 Of note, Schimmer et al43 reported an inverse relationship between number of sternal wires and risk of sternal would infection.

Table 4.

Risk Factors Associated with Sternal Wound Complications

| Primary Risk Factors | Secondary Risk Factors |

|---|---|

|

|

CCS = Canadian Cardiovascular Society Anginal Classification; NYHA = New York Heart Association Heart Failure Classification

The Relationship Between Activities and Sternal Complications

To date, there is no direct evidence linking postoperative activity level or arm movement to increased risk for sternal complications. Yet, activity limitations are often employed following median sternotomy with the clinical assumption that this will reduce risk of sternal instability and mediastinitis. What do we actually know about “sternal precautions?” Simply answered, not very much. Most of what is currently done in clinical practice is based on anecdotal evidence and expert opinion. Some indirect evidence is provided by cadaver studies using material engineering approaches. Cohen and Griffin47 evaluated the biomechanical properties of 3 different sternotomy closure techniques and found that sternal separation occurred as a result of wires cutting through bone. Also, sternal distraction (2.0 mm) occurred with the least force in the lateral direction and the greatest force in the rostral-caudal direction with anterior-posterior force intermediate.47 In another investigation, greater separation occurred at the lower end of the sternum than the upper.48

Some studies have provided indirect evidence of the stresses imposed on the sternum during different activities and exercises. Recently, El-Ansary and colleagues25,49 examined a variety of upper body activities in patients with chronic sternal instability. In this patient population, pushing up from a chair during sit-to-stand transfers created the greatest sternal separation and elevating both arms simultaneously overhead produced the least amount of sternal separation. They also found that patients with chronic sternal instability experienced the greatest amount of pain during transitions from supine to short sitting and sudden loss of balance but the least amount of pain when reaching above shoulder height.25,49 In addition, Irion et al50,51 measured supra-sternal skin movement during a variety of daily activities and found the greatest skin movement during sit-to-stand and supine-to-long sitting transfers using upper extremities and the least movement when lifting containers up to 1 gallon of water (approximately 8 lbs). It has also been suggested that upper extremity movements against resistance and/or above shoulder height (> 90° of flexion and abduction), especially those that are unilateral and weighted, place undue stress on the healing sternum. In fact, it has been reported that patients with chronic sternal instability experience pain more often with upper extremity activities that are unilateral and loaded (78%) as compared to unilateral without a load (25%), bilateral and loaded (9%), and bilateral without a load (12.5%).25 In a pilot study, Adams and colleagues52 measured the force required to complete 32 activities of daily living and found that a majority of them elicited forces of greater than the 10 lbs that is typically used to instruct patients post-sternotomy of ‘lifting’ restrictions. Interestingly, some of the greatest forces were necessary to open and close doors.52

Strategies to Reduce Sternal Complications

Several prevention strategies have been investigated for patients undergoing median sternotomy aimed at reducing the incidence of sternal instability, dehiscence, and/or mediastinitis. Alternate techniques for wiring the sternal halves may provide better stability and therefore reduce complication rates.47,53 When evaluating the biomechanical properties of 3 different sternotomy closure techniques (stainless-steel figure-of-eight wires, figure-of-eight cables, and dynamic fixation plates), Cohen et al47 found that the plate and cable systems were superior to the wire system especially during transverse and longitudinal forces. In addition, the plate system substantially reduced cutting into the sternal model as compared to the wire and cable systems during distraction and longitudinal forces. The use of metal plates to approximate the sternal borders following median sternotomy is a promising intervention, particularly for patients at risk for sternal complications.47,54–57 Snyder et al56 found that primary sternal plating in high risk patients (obesity, manual laborer, osteoporosis, intraoperative transverse sternal fracture) resulted in no early sternal complications (vs. 12% in the control group) and a decreased length of hospital stay. Recently, Gorlitzer and colleagues58,59 have investigated the effects of a sternal harness (Posthorax® Vest) used following median sternotomy and reported decreased hospital length of stay and reoperative rates as compared to a control group. Certainly, clinical use of external thoracic support (‘splinting’) during coughing and other activities that place stress on the sternum is almost universally employed with the rationale that it protects the incision and thereby reduces risk of sternal complications.60,61 In fact, the premise of patients following SP or specific activity restriction is the belief that avoiding certain movements will reduce risk of sternal complications.

Treatment of sternal instability, dehiscence, and or mediastinitis usually requires invasive procedures, but recently nonsurgical approaches to patient management have emerged. Traditionally sternal complications required surgical debridement, lavage, and reclosure.28 Use of metal plates to stabilize the sternal halves in cases of nonunion has shown promising results in several studies.62,63 When sternectomy is necessary, a flap repair is performed using skeletal muscle (typically rectus abdominus or latissimis dorsi) or the omentum as the donor tissue.64,65 Vacuum assisted closure (VAC) therapy has also been used successfully in patients with sternal wound complications.32 Gill and colleagues66 used pulsed ultrasound therapy (40 minutes per day for 3 months) over the entire sternal surface for a patient with chronic nonunion and reported complete bony union and pain resolution. El-Ansary et al67 recently investigated the effects of supportive devices in patients with chronic sternal instability and found that use of an adjustable fastening brace improved pain and lessened sternal separation. Also, in patients with chronic sternal instability, a series of trunk stabilization exercises performed for 10 minutes, twice daily, over a 6-week period resulted in less sternal separation (decreased by 6.2 mm) and less pain (decreased 14 mm on a 10 cm visual analog scale) during activity.68

Functional Consequences and Symptom Impact of Median Sternotomy

Following cardiac surgery many surgery specific factors produce adverse symptoms and interfere with patient function.69 Common symptoms and functional limitations after cardiac surgery include incisional sternotomy pain and drainage, respiratory problems, feelings of weakness, sleeping difficulties due to chest wall pain with side lying; problems with wound healing; thoracic pain; dissatisfaction with postoperative supportive care; problems with eating; pain in the shoulders, back, and neck; and ineffective coping.70–73 Hunt et al74 found that surgery-associated pain persisted in patients 12 months following cardiac surgery. Sternal wound pain was present in 61% of the patients with 18% describing the pain as severe and that pain was associated with a poor quality of life. Moore72 found that chest incisional pain was reported by 25% of women and 60% of men 3 weeks following cardiac surgery. Zimmerman et al75 examined symptoms in patients 2, 4, and 6 weeks after cardiac surgery and found that shortness of breath, fatigue, and pain were common and related to function. In a separate study, they also found that an intensive (daily for 6 weeks following hospital discharge) education intervention focusing on self-efficacy to enhance beliefs and capabilities to manage prospective situations using telehealth technology reduced symptom influence with physical activity in patients recovering from CABG surgery.76 DiMattio et al77 found a significant relationship between pain and functional status during the first 6 weeks of recovery in patients following cardiac surgery. In addition, the sternotomy scar is often perceived as disfiguring, that in turn sometimes negatively influences self-esteem and self-confidence, especially in women who have undergone cardiac surgery.78,79 Persistent chest wall pain following median sternotomy is common and has been termed Post-Coronary Artery Bypass Pain Syndrome. Carle et al80 found that the incidence of this syndrome reported by patients was high (46%) despite that a surprisingly low incidence was estimated by cardiothoracic surgeons. Biyak and colleagues81 postulated that post-sternotomy chest pain and paresthesia may be due to neuropathic pain and recently reported that pharmacological intervention (gabapentin and diclofenac) targeted towards this type of pain improved patient symptoms. Also, early postoperative pain has been shown to be lower when the pleural integrity is preserved during median sternotomy.82 Lastly, King et al83 reported that 47% of women recovering from sternotomy still reported having incision or breast pain 12 months after cardiac surgery. They also found that increasing chest circumference and harvesting of bilateral internal mammary arteries were associated with ongoing incisional pain.

Previous studies examining the effects of CABG surgery and median sternotomy provide information on the potential impact of these procedures on patient functional status.84 In a cross-sectional study that involved patients entering an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program, results demonstrated that function was more limited in patients surgically treated than those medically treated.84 Another investigation demonstrated that quality of life scores for physical functioning, role limitation due to physical health, and pain were decreased from presurgery as compared to 2 weeks postcardiac surgery and they returned to baseline values at 2 months post-CABG surgery.85 Significant differences over time were found in patients’ ability to perform daily tasks that involved vigorous and moderate activities, lifting or carrying groceries, walking more than a mile, and bathing or dressing. Depressed physical function immediately following cardiac surgery may be related to surgeon dictated SP, fear of activity, and/or pain exacerbated by movement.86 Results also showed that 2 months after CABG surgery many patients reported difficulty and/or pain with mobility, personal care, and hand activity tasks. Two months following CABG surgery many patients reported deficits in performing home chores needing assistance (36%), having difficulty (56%), and/or experiencing pain (44%).85,86 Another study found that patients who had undergone CABG surgery in the past 6 months frequently reported chest incision tenderness/ irritation (69%), chest incision numbness/tingling (50%), and waking multiple times at night (75%).87,88 Using a pain diagram, 20% of these study participants indicated having pain over the sternum.87,88 At the time of hospital discharge following cardiac surgery, another study found that 24% to 40% of patients had difficulty and 16% to 36% of patients had pain with personal care and hand activities.89 Although these findings cannot be directly attributed to only the consequences of median sternotomy, they are most likely strongly influenced by this iatrogenic effect. Interestingly, one year after CABG surgery 36% of patients subjectively reported their functional status was ‘unsatisfactory.’90 Overly restrictive SP may contribute the functional limitations by directly causing decreased muscle strength and connective tissue mobility and or indirectly by reducing habitual physical activity level.

One potential reason for such prolonged unsatisfactory functional status in many patients after CABG surgery may be the substantial change that occurs in pulmonary function and thoracic motion after a median sternotomy.91–93 The percent change in maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressure (MIP & MEP, respectively) as well as respiratory rates after median sternotomy were compared to preoperative measures.91 The MEP was most adversely affected after median sternotomy with almost a 50% reduction at one week postsurgery and was still reduced by 25% at 12 weeks postsurgery. The MIP was also adversely affected and was 17% lower than before surgery at one week postsurgery and worsened to 20% at 12 weeks postsurgery. The respiratory rate increased more than 30% at one week postsurgery and decreased, but was still approximately 5% higher than before surgery at 12 weeks postsurgery.91

At one week postsurgery, pulmonary function was between 30% to 40% lower than before surgery and while improved by 12 weeks postsurgery, still remained 10% to 15% lower than before surgery. One week after median sternotomy, the total lung capacity and functional residual capacity were reduced by 22% and 17%, respectively, and returned to near preoperative levels by 12 weeks after surgery. However, despite the residual volume being reduced only 2% at week 1 postsurgery, it increased to approximately 6% at week 12 postsurgery.91 Such a finding is concerning and suggestive of lung hyperinflation or incomplete emptying of the lungs due to sternal pain that occurred weeks after median sternotomy.

Chest wall excursion was also affected by median sternotomy.91 Upper chest motion was most adversely affected (almost 90% less than before surgery) and while improved by 12 weeks after sternotomy, was still reduced by more than 40% from preoperative levels. Thoracic motion in other areas were reduced from 20% to more than 40% at 1 week postsurgery and returned to near preoperative levels, but remained less than before surgery at 12 weeks postsurgery.91

WHY IS CHANGE NEEDED?

Currently the use of SP has created a number of quandaries for clinicians and patients. There is no universally accepted definition causing application of SP to be largely arbitrary. The information on which SP are based is often anecdotal or based on expert opinion and at best supported by indirect evidence. In most cases SP are applied uniformly for all patients over a given timeframe without regard to individual differences, risk factors for complications, and clinical status of the recovery processes. By overly restricting physical activity, optimal sternal healing may be hindered due to insufficient stress on the connective tissue structures of the chest wall. Furthermore, restricting functional tasks and exercise is likely to hinder optimal physiologic recovery. Such restriction, therefore, has the potential to promote physiological disuse atrophy and the numerous consequences associated with it, such as pain and impaired pulmonary and chest wall function.94

Currently, many clinicians and researchers are questioning whether SP are too restrictive. Parker et al95 demonstrated that the force across the median sternotomy during a cough was greater than during lifting activities including lifting 40 lb weights. They concluded that the “strength of the repair is significantly greater than is implied by the recommendation to ‘not lift more than 5 lbs.’” Others have described sternal precautions as, “…vague and/or overly restrictive, limiting the ability of cardiac rehabilitation programs to help patients achieve their desired levels of daily activity in a timely manner…”52 Recently, Brocki and colleagues61 published an extensive literature review of factors leading to sternal complications from which they developed activity recommendations. Ironically, although their purpose was to create less restrictive evidence-based guidelines for activity following sternotomy, many of their recommendations were vague (“keep upper arms to the body” and “loaded movements”), relatively conservative (in place for 6-8 weeks), and not amenable to adaptation or progression. For example, “Loaded movements of the arms should be done at a pain-free level, keeping the upper arms to the body during the initial 6 to 8 weeks following sternotomy.”61

The benefits of physical activity and exercise on health and recovery from illness are copious and well-known. Healing and remodeling of connective tissue, including bone, requires appropriate loading to facilitate development of ideal structural architecture for tensile strength and extensibility. In addition, restricted movement and activity will lead to shortening of connective tissue structures and weakening of skeletal muscle.94 There are also beneficial effects of upper body exercise on arm and chest wall circulation that in turn promotes healing.96 Therefore, the optimal degree and duration of activity restriction should be based on the patient's characteristics (risk factors, comorbidities, previous activity level, etc.) and should have a progression of activity in stages.

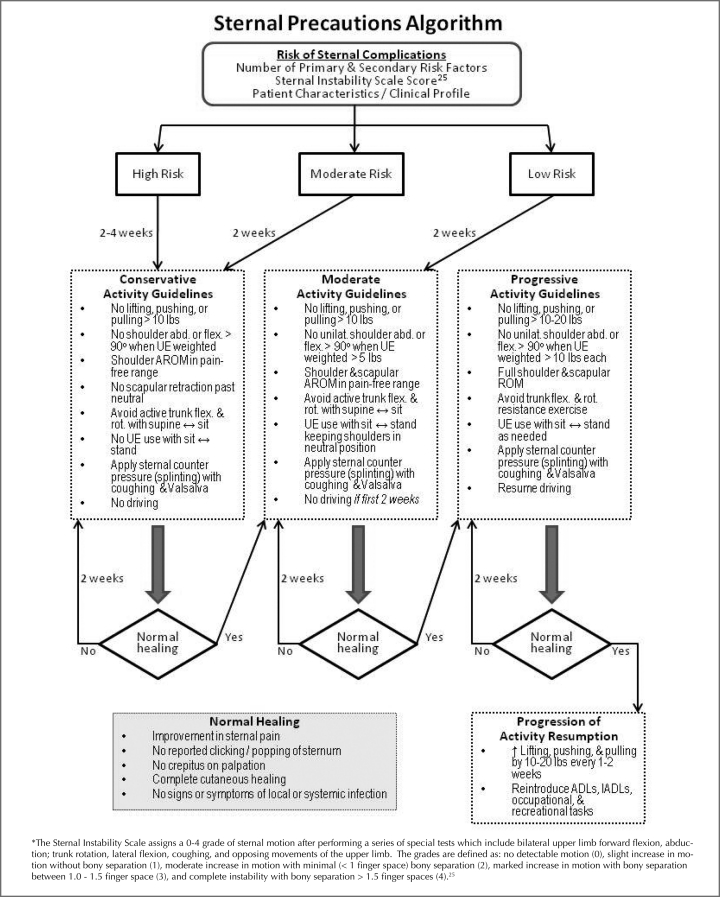

Figure 3 presents a proposed algorithm that allows less restrictive and more individual, dynamic application of SP. The first part of the model proposes placing patients in a risk category for sternal complications based on known risk factors, clinical evaluation of the wound characteristics, and other patient factors. Then, based on patient risk, the type and degree of activity precautions could be determined more specifically for each situation. Lastly, this model allows progression of activity based on patient recovery characteristics rather than a sudden lifting of all precautions at an arbitrary timepoint.

Figure 3.

Theoretical algorithm for determining type and duration of activity restrictions for patients following median sternotomy.

Example cases using this type of model:

A 21-year-old male college athlete who had undergone a single valve replacement could be considered at Low Risk for sternal complications and instructed to use the Moderate Activity Guidelines for 2 weeks. If after 2 weeks he has normal healing he could move on to the Progressive Activity Guidelines and then by 4 weeks postcardiac surgery resume normal activity.

An 85-year-old woman who has multiple risk factors for sternal complications (diabetes, osteoporosis, COPD, large breast size) who had CABG surgery could be considered High Risk for complications and instructed to use the Conservative Activity Guidelines for 2 weeks. If after 2 weeks she has incomplete cutaneous healing and sternal pain, she could be instructed to follow the same precautions for 2 more weeks. If after 4 weeks she has normal healing, she could move on to the Moderate and Progressive Activity Guidelines for 2 weeks each and by 8 weeks postcardiac surgery resume normal activity.

CONCLUSION

Traditional SP that are currently provided to patients after a median sternotomy are more restrictive than precautionary. A precautionary approach rather than restrictive approach is likely to better facilitate optimal sternal healing and functional recovery after a median sternotomy. Literature strongly suggests that progressive rehabilitation for patients after CABG surgery is needed to improve thoracic motion, pulmonary function, symptoms, and functional status after a median sternotomy. In view of these findings, SP are in need of change. Only through more active rehabilitation performed with patient-specific precautions will the above impairments improve. In fact, the current restrictive SP may be related to the poorer outcomes that have been observed in patients after median sternotomy. Therefore, patient-specific SP that focus on function and patient characteristics may be more likely to facilitate recovery after median sternotomy and less likely to impede it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Certo MC, DeTurk WE, Cahalin LP. History of cardiac rehabilitation. In: DeTurk WE, Cahalin LP, editors. Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2004. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pratt JH. Rest and exercise in the treatment of heart disease. South Med J. 1920;13:481–485. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fothergill JM. Handbook of Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: HC Lea; 1877. p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallory GK, White PD, Salcedo-Salgar J. The speed of healing of myocardial infarction: A study of the pathologic anatomy in 72 cases. Am Heart J. 1939;18:647–671. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jetter WW, White PD. Rupture of the heart in patients in metal institutions. Ann Intern Med. 1944;21:783–802. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine SA. Some harmful effects of recumbency in the treatment of heart disease. JAMA. 1944;126:80–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine SA, Lown B. Armchair treatment of acute coronary thrombosis. JAMA. 1952;148:1365. doi: 10.1001/jama.1952.02930160001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckwith JR, Kenodle DT, Sehew AE, Wood JE. Management of myocardial infarction with particular reference to armchair treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1954;41:1189–1195. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-41-6-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JL, Ward JH., Jr Acute myocardial infarction treated by the chair rest regimen. JAMA. 1954;155:226–230. doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.03690210004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson BD, Pairo A, Yuhasz M, Rechnitzer PA, Pickard HA, Lefcoe N. Psychological effects of an exercise program on post infarct and normal men. J Sports Med. 1967;7:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce EN, Frederick R, Bruce RA, Fisher L. Comparison of active participants and dropouts in CAPRI cardiopulmonary programs. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kentala E. Physical fitness and feasibility of physical rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in men of working age. Ann Clin Res. 1972;9(suppl):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanne H. Exercise tolerance and physical training of non-selected patients after myocardial infarction. Acta Med Scand. 1973;551:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frye RL, Frommer PL. Concensus development conference on coronary artery bypass surgery: medical and scientific aspects. Circulation. 1982;65(suppl 2):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konstantinov IE. The first coronary artery bypass operation and forgotten pioneers. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1522–1523. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00928-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson G, Froelicher VF, Utley JR. Continuing medical education: rehabilitation of the coronary artery bypass graft patient. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1984;4:74–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2009 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canver CC. Conduit options in coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest. 1995;108:1150–1155. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Sports Medicine . ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dafoe WA, Koshal A. Pashkow FJ, Defoe WA. Clinical Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Cardiologist's Guide. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1999. Noncardiologic complications of coronary artery bypass surgery and common patient concerns; pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grevious MA, Henry GI, Ramaswamy R, Grubb KJ. Chest reconstruction, sternal dehiscence. Web site http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1278627-overview Accessed June 4, 2010.

- 22.Personal communication with Rehabilitation Director, Mary Greeley Medical Center, Ames, Iowa, 2004.

- 23.Cahalin LP, Saponaro CM, Zuckerman JL, Krumpelbeck M, Kelliher C. A cardiothoracic surgeons perspective on sternal precautions: Implications for rehabilitation professionals. Chest 2009. http://meeting.chestpubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/136/4/98S

- 24.Crabtree TD, Codd JE, Fraser VJ, Bailey MS, Olsen MA, Damiano RJ. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for deep and superficial sternal infection after coronary artery bypass grafting at a tertiary care medical center. Sem Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;16:53–61. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Ansary D, Waddington G, Adams R. Relationship between pain and upper limb movement in patients with chronic sternal instability following cardiac surgery. Physiother Theory Prac. 2007;23(5):273–280. doi: 10.1080/09593980701209402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robicsek F, Fokin AA, Cook J, Bhatia B. Sternal instability after midline sternotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;4:1–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baskett RJF, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Is mediastinitis a Preventable Complication? A 10-year review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:462–465. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Disruption and infection of median sternotomy: a comprehensive review. Euro J Cardio-thorac Surg. 2002;21:831–839. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mekontso D, Vivier E, Girou E, Brun-Buisson C, Kirsch M. Effect of time to onset on clinical feature and prognosis of post sternotomy mediastinitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Ramzisham AR, Raflis AR, Khairulasri MG, Fikri AM, Zamrin MD. Figure-of-eight vs. interrupted sternal wire closure of median sternotomy. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:587–591. doi: 10.1177/0218492309348948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridderstolpe L, Gill H, Granfeldt H, Ahlfeldt H, Rutberg H. Superficial and deep sternal wound complications: incidence, risk factors and mortality. Eur J Cardio-thor Surg. 2001;20:1168–1175. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diez C, Koch D, Kuss O, Silber RE, Friedrich I, Boergermann J. Risk factors for mediastinitis after cardiac surgery – a retrospective analysis of 1700 patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;2:23–30. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howlader M, Smith J, Madden B. An approach to improve early detection of sternal wound infection. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2009;35(1):11–14. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v35i1.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeitani J, Penta de Peppo A, Moscarelli M, et al. Influence of sternal size and inadvertent paramedian sternotomy on stability of the closure site: a clinical and mechanical study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olbercht VA, Barreiro CJ, Bonde PN, et al. Clinical outcomes of noninfectious sternal dehiscence after median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:902–908. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldsborough MA, Miller MH, Gibson J, et al. Prevalence of leg wound complications after coronary artery bypass grafting: determination of risk factors. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8(3):149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Ansary D, Adams R, Toms L, Elkins M. Sternal instability following coronary artery bypass grafting. Physiother Theory Prac. 2000;16(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strecker T, Rosch J, Horch RE, Weyand M, Knesser U. Sternal wound infections following cardiac surgery: risk factor analysis and interdisciplinary treatment. Heart Surg Forum. 2007;10:E366–E371. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20071079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu JCY, Grayson AD, Jha P, Srinivasan AK, Fabri BM. Risk factors for sternal wound infection and mid-term survival following coronary artery bypass surgery. Euro J Cardio-thorac Surg. 2003;23:943–949. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bitkover CY, Gardlund B. Mediastinitis after cardiovascular operations: a case-control study of risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohli M, Yuan L, Escobar M, et al. A risk index for sternal surgical wound infection after cardiovascular surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:17–25. doi: 10.1086/502110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savage EB, Grab JD, O'Brien SM. Use of both internal thoracic arteries in diabetic patients increases deep sternal would infection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schimmer C, Reents W, Berneder S, et al. Prevention of sternal dehiscence and infection in high-risk patients: a prospective reandomized multicenter trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(2):707–708. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trick WE, Scheckler WE, Tokars JL, et al. Modifiable risk factors associated with deep sternal site infections after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:108–114. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(00)70224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arom KV, Emery RW, Flavin TF, Petersen RJ. Cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1562–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagni S, Salloum EJ, Tobin GR, VanHimbergen DJ, Spence PA. Serious wound infections after minimally invasive coronary bypass procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:92–94. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen DJ, Griffin LV. A biomechanical comparison of three sternotomy closure techniques. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGregor WE, Trumble DR, Magovern JA. Mechanical analysis of midline sternotomy wound closure. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Ansary D, Waddington G, Adams R. Measurement of non-physiological movement in sternal instability by ultrasound. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1513–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irion G. Effect of upper extremity movement on sternal skin stress. Acute Care Perspectives. 2006;15:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Irion G, Boyte B, Ingram J, Kirchem C, Weathers J. Sternal skin stress produced by functional upper extremity movements. Acute Care Perspectives. 2007;16:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams J, Cline MJ, Hubbard M, McCullough T, Hartman J. A new paradigm for post-cardiac event resistance exercise guidelines. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma R, Puri D, Panigrahi BP, Virdi IS. A modified parasternal wire technique for prevention and treatment of sternal dehiscence. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:210–213. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plass A, Grunenfelder J, Reuthebuch O, et al. New transverse plate fixation system for complicated sternal wound infection after median sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1210–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raman J, Song DH, Bolotin G, Jeevanandam V. Sternal closure with titanium plate fixation – a paradigm shift in preventing mediastinitis. Interactive Cardiovasc Thor Surg. 2006;5:336–339. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2005.121863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snyder CW, Graham LA, Byers RE, Holman WL. Primary sternal plating to prevent sternal wound complications after cardiac surgery: early experience and patterns of failure. Interactive Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:763–766. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.214023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song DH, Lohman RF, Renucci JD, Jeevanandam V, Raman J. Primary sternal plating in high-risk patients prevents mediastinitis. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg. 2004;26:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gorlitzer M, Folkmann S, Meinhart J, et al. A newly designed thorax support vest prevents sternum instability after median sternotomy. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2009;36:335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorlitzer M, Wagner F, Pfeiffer S, et al. A prospcetive randomized multicenter trial shows improvement of sternum related complications in cardiac surgery with the Posthorax® support vest. Interactive Cardiovasc Thor Surg. 2009;36:335–339. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.223305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sobush DC. Is the application of external thoracic support following median sternotomy a placebo or a prudent intervention strategy? Resp Care. 2008;53(8):1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brocki BC, Thorup CB, Andreasen JJ. Precautions related to midline sternotomy in cardiac surgery: A review or mechanical stress factors leading to sternal complications. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voss B, Bauemschmitt R, Will A, et al. Sternal reconstruction with titanium plates in complicated sternal dehiscence. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(1):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huh J, Bakaeen F, Chu D, Wall MJ. Transverse sternal plating in secondary sternal reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(6):1476–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cabbabe EB, Cabbabe SW. Surgical management of the symptomatic unstable sternum with pectoralis major muscle flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1495–1498. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a07459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hameed A, Akhtar S, Naqvi A, Pervaiz Z. Reconstruction of complex chest wall defects by using polypropylene mesh and a pediciled latissimus dorsi flap: a 6-year experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(6):628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gill IPS, Montgomery RJ, Wallis J. Successful treatment of sternal non-union by ultrasound. Interactive Cardio-Vasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:389–390. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.196600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Ansary D, Waddington G, Adams R. Control of separation in sternal instability by supportive devices: a comparison of an adjustable fastening brace, compression garment, and sports tape. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1775–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Ansary D, Waddington G, Adams R. Trunk stabilisation exercises reduce sternal separation in chronic sternal instability after cardiac surgery: a randomized cross-over trial. Austral. J Physiother. 2007;53:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(07)70006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaPier TK, Schenk R. Thoracic musculoskeletal considerations following open heart surgery. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2002;13(4):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Edell-Gustafsson UM, Hetta JE, Aren GB, Hamrin EK. Measurement of sleep and quality of life before and after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract. 1997;3(4):239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172x.1997.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson G, Feleke E, Perski A. Patient-perceived quality of life after coronary bypass surgery Experienced problems and reactions to supportive care one year after the operation. Scand J Caring Sci. 1999;13:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore SM. A comparison of women's and men's symptoms during home recovery after coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart Lung. 1995;24:495–501. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(95)80027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tack BB, Gilliss CL. Nurse-monitored cardiac recovery: a description of the first 8 weeks. Heart Lung. 1990;19:491–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunt JO, Hendrata MV, Myles PS. Quality of life 12 months after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Heart Lung. 2000;29:401–411. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.110578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zimmerman L, Barnason S, Brey BA, Catlin SS, Nieveen J. Comparison of recovery patterns for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass in the early discharge period. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:132–141. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zimmerman L, Barnason S, Nieveen J, Schmaderer M. Symptom management intervention in elderly coronary artery bypass graft patients. Outcomes Manag. 2004;8:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DiMattio MJ, Tulman L. A longitudinal study of functional status and correlates following coronary artery bypass graft surgery in women. Nurs Res. 2003;52:98–107. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kantoch MJ, Eustace J, Collins-Nakai RL, Taylor DA, Boisvert JA, Lysak PS. The significance of cardiac surgery scars in adult patients with congenital heart disease. Kardiol Pol. 2006;64:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.King K, McFetridge-Durdle J, LeBlanc P, Anzarut A, Tsuyuki R. A descriptive examination of the impact of sternal scar formation in women. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carle C, Ashwörth A, Roscoe A. A survey of post-sternotomy chronic pain following cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(12):1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06169_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Biyik I, Gülcüler M, Karabiga M, Ergene O, Tayyar N. Efficacy of gabapentin versus diclofenac in the treatment of chest pain and paresthesia in pain with sternotomy. Anàdolu Kardiyol Derg. 2009;9(5):390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gullu AU, Ekinci A, Sensoz Y, et al. Preserved pleural integrity provides better respiratory function and pain score after coronary surgery. J Card Surg. 2009;24:374–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.King K, Parry M, Southern D, Faris P, Tsuyuki R. Women's recovery from sternotomy-extension (WRESTE) study: examining long-term pain and discomfort following sternotomy and their predictors. Heart. 2008;94(4):493–497. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.117606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.LaPier TL. Functional status during acute recovery following hospitalization for coronary artery disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:203–207. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200305000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.LaPier TL, Wintz C, Holmes W, et al. Analysis of activities of daily living performance in patients recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. J Phys Occupational Ther Geriatrics. 2008;27(1):16–35. [Google Scholar]

- 86.LaPier TL. Functional status of patients during sub-acute recovery from coronary artery bypass: cross-sectional analysis of multiple domains. Heart Lung. 2007;36(2):114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.LaPier TL, Wilson B. Prevalence and severity of symptoms in patients recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. Acute Care Perspectives. 2007;16(3):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 88.LaPier TL. Psychometric evaluation of the Heart Surgery Symptom Inventory in patients recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26:101–106. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.LaPier TL, Wilson B. Functional deficits at the time of hospital discharge in patients following coronary artery bypass surgery. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2006;17:144. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Falcoz PE, Chocron S, Stoica L, et al. Open heart surgery: one-year self-assessment of quality of life and functional outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1598–1604. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00730-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Locke TJ, Griffiths TL, Mould H, Gibson GJ. Rib cage mechanics after median sternotomy. Thorax. 1990;45:465–468. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.6.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ragnarsdottir M, Kristjansdottir A, Ingvarsdottir I, et al. Short-term changes in pulmonary function and respiratory movements after cardiac surgery via median sternotomy. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2004;38:46–52. doi: 10.1080/14017430310016658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kristjansdottir A, Ragnarsdottir M, Hannesson P, et al. Respiratory movements are altered three months and one year following cardiac surgery. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2004;38(2):98–103. doi: 10.1080/14017430410028492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lieber R. Skeletal Muscle Structure, Function, and Plasticity. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Parker R, Adams JL, Ogalo G, et al. Current activity guidelines for CABG patients are too restrictive: a comparison of the forces exerted on the median sternotomy during a cough vs. lifting activities combimed with valsalva maneuver. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56(4):190–194. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Harms CA. Effect of skeletal muscle demand on cardiovascular function (Review) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(1):94–99. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.The Heart Institute at Providence Everett Medical Center, Everett WA. A Patient's Guide to Cardiac Surgery, Treatment and Rehabilitation and Diet for a Healthy Heart. Available at: http://www.ectsa.net/31563all.pdf Accessed on November 11, 2010.