Abstract

For the past two decades, salivary diagnostic approaches have been developed to monitor oral diseases such as periodontal diseases and to assess caries risk. Recently, the combination of emerging biotechnologies and salivary diagnostics has extended the range of saliva-based diagnostics from the oral cavity to the whole physiological system as most compounds found in blood are also present in saliva. Accordingly saliva can reflect the physiological state of the body, including emotional, endocrinal, nutritional and metabolic variations and provides a source for the monitoring of oral and also systemic health. This review presents the current status of saliva diagnostics and delves into their applications to the discovery of biomarkers for cancer detection and therapeutic applications. Translating scientific findings of nucleic acids, proteins and metabolites in body fluids to clinical applications is a cumbersome and challenging journey. Our research group is pursuing the biology of salivary analytes and the development of technologies in order to detect distinct biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity. The avenue of saliva diagnostics incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic findings will enable us to connect salivary molecular analytes to monitor therapies, therapeutic outcomes, and finally disease progression in cancer.

Keywords: saliva diagnostics, biomarker, transcriptome, proteome, therapeutic perspectives

Introduction

Human saliva is a clear, slightly acidic (pH=6.0-7.0) biological fluid containing a mixture of secretions from multiple salivary glands, including the parotid, submandibular, sublingual and other minor glands beneath the oral mucosa as well as gingival crevice fluid. This complex oral fluid serves the execution of multiple physiological functions such as oral digestion, food swallowing and tasting, tissue lubrication, maintenance of tooth integrity, antibacterial and antiviral protection (Mandel, 1987). In addition to the important role of maintaining the homeostasis of the oral cavity system, the oral fluid is a perfect medium to be explored for health and disease surveillance.

Like blood, saliva is a complex fluid containing a variety of enzymes, hormones, antibodies, antimicrobial constituents, and cytokines (Zelles et al., 1995, Rehak et al., 2000). Many of these enter saliva from the blood by passing through cells by transcellular, passive intracellular diffusion and active transport, or paracellular routes by extracellular ultra filtration within the salivary glands or through the gingival sulcus (Drobitch & Svensson, 1992, Haeckel & Hanecke, 1993, Jusko & Milsap, 1993). So, most compounds found in blood are also present in saliva. Accordingly saliva can reflect the physiological state of the body, including emotional, endocrinal, nutritional and metabolic variations. Consequently, this fluid provides a source for the monitoring of oral and also systemic health. This is the basis of our vision to develop disease diagnostics and promote human health surveillance by analysis of saliva. In this article, we will review the current status of saliva proteomics and transcriptomics and their applications to the discovery of biomarkers for cancer detection and therapeutic applications.

Saliva Diagnostics

For the past two decades, salivary diagnostic approaches have been developed to monitor oral diseases such as periodontal diseases (Kornman et al., 1997, Socransky et al., 2000) and to assess caries risk (Baughan et al., 2000). Recently, the combination of emerging biotechnologies and salivary diagnostics has extended the range of saliva-based diagnostics from the oral cavity to the whole physiological system. Large numbers of medically valuable analytes in saliva are gradually unveiled and represent biomarkers for different diseases including cancer (Boyle et al., 1994, Li et al., 2004a, Zhang et al., 2010), autoimmune (Hu et al., 2007b, Streckfus et al., 2001), viral (Ochnio et al., 1997) (Chaita et al., 1995, El-Medany et al., 1999, Pozo & Tenorio, 1999) and bacterial (Kountoruras, 1998, Lendenmann et al., 2000) diseases as well as HIV (Emmons, 1997, Malamud, 1997). Furthermore, a growing body of evidence is getting established for cardiovascular (Adam et al., 1999) and metabolic diseases (Walt et al., 2007) such as diabetes mellitus(Rao et al., 2009, Sashikumar & Kannan, 2010). These advances have widened the salivary diagnostic approach from the oral cavity to the whole physiological system, and thus point towards a promising future for saliva diagnostics for personalized individual medicine applications including clinical decisions and post-treatment outcome predications.

Technologies for discovery of salivary biomarkers

The term, biomarker, refers to measurable and quantifiable biological parameters than can serve as indicators for health and physiology-related assessments, such as pathogenic processes, environmental exposure, disease diagnosis and prognosis or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention. Saliva is a unique body fluid for the development of molecular diagnostics as it contains not only components found in serum but also offers several advantages over serum. Saliva collection is cost-effective, safe, easy and non-invasive. However, previously available technologies did not allow the necessary screening of the complex constituents which are present in saliva at a low abundance and so its potential was frequently underestimated (Helmerhorst & Oppenheim, 2007). Promising new technologies with higher detection sensitivity have opened a new horizon finally meeting the requirements essential to successfully screen saliva components, especially proteins and nucleic acids. Studies of the salivary proteome have shown that, in addition to the major salivary protein families such as alpha-amylase, saliva contains hundreds of minor proteins or peptides defining the first salivary biomarker alphabet. These salivary proteomic markers are present in low concentrations and can play important roles in the discrimination of diseases. Saliva not only contains proteins but also nucleic acids, and thus the second salivary diagnostic alphabet, the saliva transcriptome, is currently a focus of interest. Our laboratory has developed a significant body of work and is dedicating considerable resources to investigate the transcriptome approach in saliva, and thus spearheading the detection of messenger RNA (mRNA) and microRNA in human saliva.

The salivary proteome

The capability to identify proteins and to determine their covalent structures has been central to the life sciences. The amino acid sequence of proteins provides a link between proteins and their coding genes via the genetic code, and, principally, a link between cell physiology and genetics. The identification of proteins provides an insight into complex cellular regulatory networks (Domon & Aebersold, 2006). Studying the proteome, the protein complement of the genome, in bodily fluids is valuable due to its clinical significance as source of disease markers and thus, the proteome of human salivary fluid has the potential to open new doors for disease biomarker discovery. Salivary proteins not only play a role in maintaining oral and general health but may also serve as biological markers to survey normal health and disease status. As a consequence, analysis and cataloguing of the human salivary proteome will be of great interest to researchers within the fields saliva-based diagnostics and oral biology (Hu et al., 2007c).

Saliva Proteome Knowledge Base

The complete catalogue of the salivary proteome, including its stratification according to their parotid, submandibular/sublingual origins, has been generated using state-of-the-art, sensitive and high-throughput mass spectrometry (MS) proteomic technology combined with different protein separation methods (Hu et al., 2007a, Hu et al., 2005, Wilmarth et al., 2004, Xie et al., 2005a, Xie et al., 2005b, Yan et al., 2009, Yates et al., 2006, Guo et al., 2006, Hirtz et al., 2005, Walz et al., 2006, Karas & Hillenkamp, 1988, Lee & Wong, 2009, Denny et al., 2008). This systematic study of all salivary secretory proteome components, post-translational modifications and protein complexes has been elucidated to make a description of their structure and function fully accessible and available to the public (http://www.hspp.ucla.edu). At this website, the Saliva Proteome Knowledge Base (SPKB) and the Salivary Proteome Wiki (SPW) are linked. SPW centralizes the acquired proteomic data and annotates the identified saliva proteins and is fully accessible to the public for queries. The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) will soon launch the SPW, which is a collaborative environment to share and annotate salivary proteomics data. An initial key step for saliva to be of practical use for disease diagnosis and health monitoring is the classification of its protein components. Recently, several reports aiming to comprehensively catalogue the salivary proteome have been published with numbers of proteins identified ranging from hundreds to over thousands (Hu et al., 2007b, Hu et al., 2007d, Hu et al., 2006, Hu et al., 2005, Xie et al., 2005a, Xie et al., 2005b, Guo et al., 2006, Ramachandran et al., 2006, Wilmarth et al., 2004). In 2008, an NIDCR-funded consortium study comprehensively identified and catalogued the human ductal salivary proteome and led to the compilation of 1166 proteins, out of which 914 were identified in the parotid and 917 in the submandibular and sublingual fluids, as well as 665 proteins common between the glands (for further information go to: www.hspp.ucla.edu)(Denny et al., 2008).

Human Plasma Proteome Project

It is important to compare the saliva protein composition with other established proteomes, such as plasma to understand the unique utility of the salivary proteome in the context of its function and potential diagnostic value. Overlap in protein content between saliva and plasma may indicate that saliva could be used as a diagnostic alternative to blood tests. Numerous studies have uncovered how changes in the concentrations of specific plasma proteins have been associated with disease processes, leading to well-accepted clinical applications (Kasper, 2004). To date, the plasma proteome is perhaps the most extensively studied human proteome. The international HUPO Human Plasma Proteome Project, a collaboration of many laboratories using MS technology, compiled a core dataset of 3020 distinct proteins (with a minimum of two unique peptides per protein) (Omenn et al., 2005, Omenn, 2005, Adamski et al., 2005), out of which 889 proteins were confirmed as high-confidence identifications through a rigorous statistical approach adjusting for protein length and multiple comparisons testing (States et al., 2006).

The protein compositions found in human salivary and plasma fluids are compared (Yan et al., 2009) and approximately 27% of the whole saliva proteins are found in plasma. Despite this apparently low degree of overlap, the distribution found across Gene Ontological categories such as molecular function, biological processes and cellular components shows strong similarities (Loo et al., 2010). Nearly 40% of the proteins that have been suggested to be candidate markers for cancer, cardiovascular disease and stroke can be found in whole saliva. Several sources can contribute to the overlap of protein identifications in saliva and plasma: 1) leakage of plasma into saliva through intracellular and/or extracellular routes including outflow of gingival crevicular fluid; 2) plasma and saliva may share essential proteins needed to maintain their physiological function as body fluids and 3) proteins derived from cell debris may be in close contact with either fluid.

These comparisons and correlations should encourage researchers to consider the use of saliva to discover new protein biomarkers to detect early signs of disease throughout the body. Moreover, following the diagnostic value of proteins in blood, proteomic analysis of saliva over the course of disease progression could reveal valuable biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of disease status in a noninvasive manner. Profiling the saliva proteins before and after pharmacological interventions may provide important information on drug efficacy and toxicity.

Salivary Transcriptome

Messenger (m) RNA is the direct precursor of proteins and in general the corresponding levels are correlated in cells and tissue samples (Zimmermann & Wong, 2008). Nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA are now much easier to screen in an ‘omic’ manner, and candidate disease markers can be verified by sensitive and specific PCR based methodologies allowing a relatively efficient level of throughput. Initially as an attempt to link IL-8 protein to IL-8 RNA in the same saliva supernatant in an oral cancer study, our group discovered that mRNAs are present in cell-free saliva (St John et al., 2004). Following this finding, salivary RNA of healthy subjects was profiled on gene expression arrays and more than 3000 species of mRNA were found, out of which a set of 185 mRNAs were consistently detected in healthy subjects (normal salivary core transcripts' (NSCT)) (Li et al., 2004b). The salivary transcriptome presented a second diagnostic alphabet in saliva and opened the avenue of salivary transcriptome diagnostics.

At the UCLA Dental Research Institute, we have established a robust platform to study salivary mRNA including automated extraction, purification, amplification, and high-throughput microarray screening. Moreover, we have developed statistical and informatics tools that are tailored for salivary biomarker discovery and validation. In the past years, the nature, origin and characterization of salivary mRNA have been actively pursued (Zhang et al., 2010, Li et al., 2004a, Hu et al., 2007b, Park et al., 2007, Park et al., 2006, Walz et al., 2006). Early studies from our laboratory have demonstrated the feasibility of using salivary mRNA for detection of oral cancer (Li et al., 2004a, St John et al., 2004). In parallel, human mRNAs have been applied in various fields such as among forensic scientists who use a small set of saliva-specific mRNAs to identify body fluids (Juusola & Ballantyne, 2003, Nussbaumer et al., 2006), furthermore inflammatory mRNA markers were detected in whole saliva to monitor the status of periodontal disease in type II diabetic patients (Gomes et al., 2006).

Identification of salivary transcriptomic biomarkers

At present, the main strategy to identify salivary transcriptomic biomarkers is through microarray technology. After profiling the transcriptomic biomarkers by microarray, they are validated by quantitative (q)PCR, the gold standard for quantification of nucleic acids. The application of gene expression profiling to saliva samples is hampered by the presence of partially fragmented and degraded RNAs that are difficult to amplify and detect with the prevailing technologies. Moreover, the often limited volume of saliva samples is a challenge to qPCR validation of multiple candidates. This hurdle was overcome by a study performed in our laboratory providing proof-of-concept data on the combination of a universal mRNA-amplification method for the Affymetrix all exon array for candidate selection and a multiplex pre-amplification method for validation (Hu et al., 2008b). At present, the low amounts of RNA in saliva do not hinder the reverse transcriptase (RT)-qPCR performance as a multiplex RT-PCR-based pre-amplification approach was developed allowing to accurately quantify over 50 targets from one reaction (Hu et al., 2008b). Moreover, performing simultaneously RT-reactions for different targets offers cost- and time-effectiveness and allows a small volume of pre-amplification product to be used for subsequent qPCR measurements.

Exosome discovery in human saliva

Since our initial report, we have published and accumulated an abundance of additional supporting evidence such as the characterization of salivary RNA (Li et al., 2004b) including that RNAs in saliva, similar to cell-free RNA in plasma, are protected from environmental degradation by their association with macromolecules (Park et al., 2006). Sequencing results from a saliva cDNA library demonstrated the fragmentation and the consequently missing 3′ poly-A tail of most saliva RNAs (Park et al., 2007). This is a key study as it impressively demonstrated that the detected 117 cloned salivary mRNAs did neither originate from contaminating genomic DNA nor from pseudo-genes. Conversely, all sequences were proven to be RNA from human origin. The surprising stability of the partially degraded mRNAs in saliva may be conferred by a similar mechanism as is the case in plasma. In both body fluids the RNA is associated with some macromolecule or subcellular body. More recently, salivary mRNA were localized inside salivary exosomes, and these nucleic acids were protected against ribonucleases in saliva (Palanisamy et al., 2010). Moreover, saliva exosomes have been discovered to regulate the cell-cell environment by altering their gene expression allowing us to better understand the molecular basis of oral diseases. These findings amongst others (Skog et al., 2008, Ratajczak et al., 2006, Valadi et al., 2007) open a new research perspective on the use of exosomal transfer of mRNA to target another cell type and to activate or modulate gene expression in oral keratinocytes. Currently, exosomes are intense focus of interest as they might be the key to protecting salivary RNA with their lipid bi-layers and shuttling RNA from the system (the tumor site) into saliva to target sites.

Salivary microRNA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are encoded by genes but are not translated into proteins. They are non-coding RNAs, instead each primary transcript (a pri-miRNA) is processed into a short stem-loop structure called a pre-miRNA and finally into a functional miRNA. Mature miRNA molecules are partially complementary to one or more mRNA molecules, and their main function is to down-regulate gene expression. Initially, the miRNAs lin-4 and let-7 were discovered in C. elegans (Grosshans & Slack, 2002), categorized according to mass (Lee & Ambros, 2001) and since then, the mechanism of miRNA production and mode of action has been well characterized (Zeng, 2006). Hundreds of miRNAs from various organisms have been discovered, and functional assays have established that miRNAs serve important functions in cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, stress and immune response as well as glucose secretion (Lu et al., 2005, Stadler & Ruohola-Baker, 2008, Taganov et al., 2007). In saliva, miRNA are present in both whole saliva and saliva supernatant out of which 314 of the 708 human miRNAs registered in the most recent release of miRBase version 12.0 were profiled (Park et al., 2009, Michael et al., 2010), and so the third diagnostic alphabet in saliva was established.

Proteomic and transcriptomic approaches will allow us to comprehensively profile these two salivary analytes. Moreover, combining biomarkers from both compartments could reveal if these two classes of biomarker can be synergistic for early detection, disease progression, and monitoring of disease status. Similarly, profiling the saliva proteins, mRNAs and microRNAs before and after pharmacological interventions may provide important information on drug efficacy and toxicity in the context of therapeutic responsiveness.

Molecular oncology detection based on salivary biomarkers

Multiple molecular alterations occur during cancer development. To begin to understand these processes, we need to characterize and integrate these components. Deciphering the molecular networks that distinguish progressive disease from non-progressive disease will shed light into the biology of cancer as well as lead to the identification of biomarkers that will aid in the selection of affected patients. Advances in mass spectrometric techniques have made quantitative proteomic profiling possible in tissues and fluids. However, transcript and protein abundance measurements may not always be concordant as cells have adopted elaborate regulatory mechanisms at the levels of transcription (e.g., binding of transcription factors, chromatin structure modification), post-transcription (e.g., nucleocytoplasmic export or splicing of messenger RNA, differential ribosomal loading), and post-translation (e.g., protein degradation or export) (Chan, 2006). In this regard, quantitative transcript and protein abundance measurements serve as yardsticks for each other. While similarities between protein and RNA levels increase our confidence in novel biomarkers discovery, differences may result in additional post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms as candidates for the design of therapeutics (Chan, 2006).

Salivary biomarker detection for oral squamous cell cancer

Early detection is a key question that needs to be addressed in almost all types of cancer. In oral squamous cell cancer (OSCC), if the cancer is detected at T1 stage, the five-year survival rate is 80% compared to 20-40% if the cancer is diagnosed at later stages (T3 and T4). Saliva has been used as a diagnostic medium for OSCC, and saliva analytes such as proteins (Chai & Grandis, 2006), mRNA (Li et al., 2004a) and DNA have been used to detect OSCC (Brinkman & Wong, 2006, Chai & Grandis, 2006, Hu et al., 2008b). Using proteomics and genomics technologies we have previously discovered and validated salivary OSCC markers in American patients (Li et al., 2004a, Li et al., 2004b) (St John et al., 2004).

Salivary mRNA and microRNA biomarkers for oral squamous cell cancer

The translational utility of salivary transcriptome analysis was established by the expression microarray-based discovery of a panel of oral cancer mRNA biomarkers (Li et al., 2004a). Nine candidate transcripts were chosen from a comparison of 10 early stage OSCC patients and 10 healthy matched control subjects and validated by RT-qPCR. In a validation cohort of 32 patients and 32 controls, 7 transcripts were confirmed to be elevated in OSCC with statistical significance (p<0.05 with Wilcoxon's signed rank test): DUSP1, H3F3A, IL1B, IL8, OAZ1, SAT and S100P. Combinations of these biomarkers displayed a sensitivity and specificity of up to 91% (ROC=0.95) in distinguishing patients from controls placing them amongst the most discriminatory panels of cancer biomarkers from a body fluid (Li et al., 2006). In collaboration with the National Cancer Institute's Early Disease Detection Network (EDRN), we are currently validating the salivary transcriptome biomarkers for oral cancer detection. Targeting the initially validated 7 salivary OSCC markers, over 220 additional patients have been tested (manuscript in preparation).

Investigating miRNA in saliva, two miRNAs, miR125a and miR-200a, were found to be differentially expressed in the saliva of the OSCC patients compared with controls. These findings suggest that the use of this third diagnostic alphabet in saliva can be helpful as a non-invasive and rapid diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of oral cancer (Park et al., 2009).

Proteomic salivary biomarkers for oral squamous cell cancer

After using laser-capture micro dissection, we have identified the expression of 2 cellular genes that are uniquely associated with OSCC: interleukin (IL) 6 and IL-8 (Alevizos et al., 2001). In saliva of newly diagnosed OSCC patients, IL-8 was detected at a higher concentration (p<0.01) while IL-6 was at a higher concentration in serum of OSCC patients (p<0.01). This finding indicated that Il-8 in saliva and Il-6 in serum hold promise as biomarkers (St John et al., 2004). Furthermore, our laboratory has discovered and validated a highly discriminatory panel of salivary biomarkers for oral cancer detection, showing that five salivary proteins (M2BP, MRP14, Profilin, CD59 and Catalase) were discriminatory for oral cancer with a clinical accuracy greater than 90% (Hu et al., 2008a).

Transcriptomic salivary biomarkers for pancreatic cancer

A milestone in salivary diagnostics was recently achieved with the identification of significant differential salivary transcriptome profiles between patients with early stage resectable pancreatic cancer and healthy controls (Zhang et al., 2010). Currently pancreatic cancer consistently leads to a typical clinical presentation of incurable disease at initial diagnosis because of a lack of detection technology and therefore new strategies and biomarkers for early detection are desperately needed. Zhang et al. succeeded to link the profiles of molecular signatures in saliva and their changes between disease and controls to the detection of pancreatic cancer. Based on microarray profiling, 49 transcripts were up-regulated and 21 down-regulated out of which a total of 7 up-regulated and 5 down-regulated genes were validated. These 12 mRNA biomarkers were discovered and validated showing significant differences between pancreatic cancer patients and healthy controls (P<0.05, n=60), yielding receiver-operating characteristics (ROC)-plot area under the curve (AUC) values between 0.682 and 0.823. The logistic regression model with the combination of 4 mRNA biomarkers (KRAS, MBD3L2, ACRV1 and DPM) could differentiate pancreatic cancer patients from non-cancer subjects including chronic pancreatitis and healthy controls, yielding an area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.971 with 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity. Among the 12 validated mRNA biomarkers, several genes, e.g. MBD3L2, GLTSCR2, and TPT1, have been linked to carcinogenesis (Smith et al., 2000, Kim et al., 2008, Okahara et al., 2004, Maehama et al., 2004).

In addition to OSCC and pancreatic cancer, our laboratory is currently targeting several high-impact diseases such as breast, lung and ovarian cancer using expression-based microarray analysis and RT-qPCR. Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune disease that affects 4 million Americans, primarily women (9:1) is also discriminated via salivary biomarkers (Hu et al., 2009, Hu et al., 2007b). Furthermore, xenographed mouse models are being used in order to provide functional data aiming to provide a systemic proof-of-concept for salivary biomarkers showing that human tumor markers are trafficking from the tumor site into the mouse saliva (Gao et al., 2009).

Pharmacogenomics

One of the most promising research areas for the pharmaceutical industry that emerged in the post-genomic era is pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics, broadly defined, is the study of the impact of genetic variation on the efficacy and toxicity of drugs, or the study of how a patient's genetic makeup determines the response to a therapeutic intervention (Peet & Bey, 2001). The context within which both, basic and translational pharmacogenomic sciences have developed will be a revolution in drug therapy. These advances could offer ways to maximize drug efficacy, minimize toxicity and select responsive patients. Among many factors influencing the drug response, it became clear that inheritance can be a very important factor (Vesell & Page, 1968a, Vesell & Page, 1968b). Now, it is becoming equally clear that the union of transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic with genetic data will accelerate the process of understanding the mechanisms that are responsible for variable response to the powerful therapeutic agents used currently in medicine (Wang, 2009). Evolved from a single gene approach, pharmacogenomics now incorporates pathway-based and genome-wide approaches.

Metabolomic profiles in cancer patients

Metabolomics is the study of the metabolome, which describes the repertoire of small molecules present in cells, tissues, organs and biological fluids (Dettmer & Hammock, 2004, Aharoni et al., 2002, Fiehn et al., 2000). The concentration and fluxes of these compounds result from a multifaceted interplay among gene expression, protein expression, and the environment- an environment that includes drug exposure. Metabolomics generates quantitative data for a large number of metabolites in order to understand metabolic dynamics associated with conditions such as disease or drug exposure (Kristal, 2007). This approach is in contrast to classical biochemical approaches, which often focus on single metabolites, single biochemical reactions, their kinetic properties, and/or defined sets of linked reactions. Metabolomics can complement data obtained from genomics and transcriptomics adding another ‘layer’ of data making a system approach possible to study individual variation in a disease state or during drug therapy and response.

Recently, our laboratory obtained and compared comprehensive salivary metabolic profiles of patients with oral, breast or pancreatic cancer, or periodontal disease, and healthy controls (Sugimoto et al., 2010). In this study, 57 principal metabolites that can be used to accurately predict the probability of being affected by each individual disease were identified. In all 3 cancer groups (oral, breast and pancreatic), the profiles of quantified metabolites manifested at relatively higher concentrations for most of the metabolites compared to those in people with periodontal disease and control subjects. This body of evidence suggests cancer specific signatures are embedded in saliva metabolites. AUCs were calculated to discriminate healthy controls from each disease. The AUCs were outstanding: 0.865 for oral cancer, 0.973 for breast cancer, 0.993 for pancreatic cancer, and 0.969 for periodontal diseases.

The application of genome-wide techniques to perform ‘pharmacogenomic’ studies is in its infancy. Genomics, transcriptomics and even metabolomics are beginning to be applied to integrate studies of drug response, which clearly highlights the need for a system biology approach. These developments promise to substantially enhance our functional and mechanistic understanding of causes of variation in drug-response phenotypes and to help moving towards individualized drug therapy and personalized medicine (Wang, 2009).

Saliva ontology

The rapid development and maturity of the genomics field has led to the emergence of other ‘omics’ studies, such as proteomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics, which are now being widely implemented in studies of human disease. Furthermore, mining the data from multiple ‘omics’ studies can give deeper insight into biological systems than can be obtained from any single ‘omics’ study and thus ‘omics’ databases such as PharmGKB (the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base, www.pharmgkb.org) and EPO-KB (the Empirical Proteomic Ontology Knowledge Base, www.dbmi.pitt.edu/EPO-KB) serve as important resources for emerging disciplines of system biology.

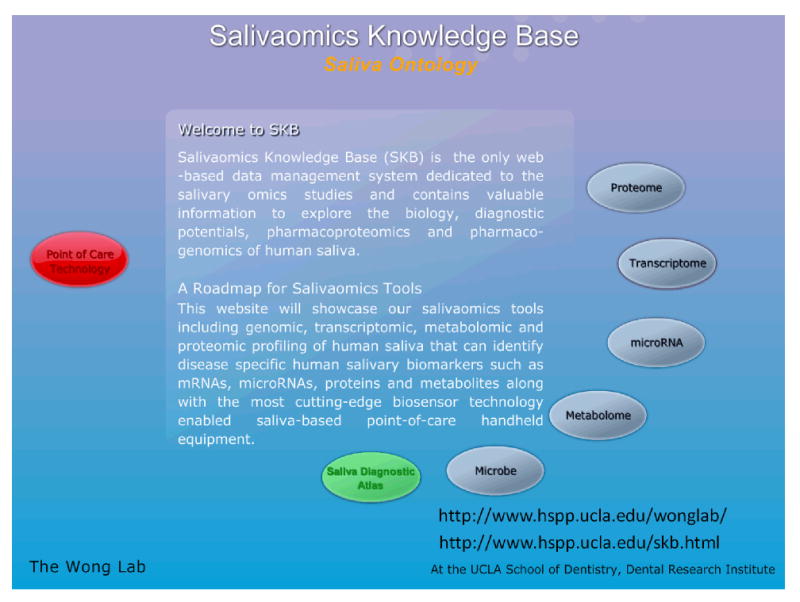

Saliva has not been widely integrated in ontology and terminology resources yet (Lisacek et al., 2006). Just recently, the Salivaomics Knowledge Base (SKB) has been created by aligning the salivary biomarker discovery and validation resources at UCLA (Figure 1) with the ontology resources developed by the OBO (Open Biomedical Ontologies) Foundry (www.obofoundry.org), including the new Saliva Ontology (SALO) (Ai et al., 2010). The SKB is a data repository, management system and web resource constructed to support human salivary proteomics, transcriptomics, miRNA, metabolomics and microbiome research. The SKB will provide the first web resource dedicated to salivary ‘omics’ studies. It will contain the data and information needed to explore the biology, diagnostic potentials, pharmacoproteomics and pharmacogenomics of human saliva (SKB; http://www.skb.ucla.edu/). Overall, the SKB will allow a systems approach to the utilization of salivary diagnostic technology for personalized medicine applications.

Figure 1.

The Salivaomics Knowledge Base (SKB) has been created by aligning the salivary biomarker discovery and validation resources at UCLA with the ontology resources developed by the OBO (Open Biomedical Ontologies) Foundry (www.obofoundry.org), including the new Saliva Ontology (SALO). The SKB is a data repository, management system and web resource constructed to support human salivary proteomics, transcriptomics, miRNA, metabolomics and microbiome research.

SALO is a consensus-based controlled vocabulary of terms and relations dedicated to the salivaomics domain and to saliva-related diagnostics following the principles of the OBO Foundry. SALO was defined based on cross-disciplinary interaction between saliva and protein experts, diagnosticians, and ontologists (SALO; http://www.skb.ucla.edu/SALO/). In order to improve development and testing of SALO, a corpus of saliva-relevant literature was incrementally developed in SKB to assist in identifying core terms, synonyms and definitions for inclusion within the ontology, and to provide examples of usage and links between SALO content and the corresponding items through their PubMed identifiers. A growing body of semantically enhanced web-enabled literature will be created within the SKB to support future research.

Point-of-Care Technology

Early detection is a key question that needs to be addressed in almost all types of diseases. The analysis of body fluids offers a great opportunity to detect diseases at an earlier stage. Saliva diagnostics are very attractive because of noninvasive sample collection and simple sample processing. For patients, the noninvasive saliva collection procedure reduces anxiety and discomfort and is easily accessible compared to tissue biopsies. Therefore, developing highly sensitive and accurate assays for salivary mRNA/protein biomarkers makes saliva a valuable diagnostic fluid (Herr et al., 2007, Gormally et al., 2006).

Single biomarker detection is not effective enough for accurate diagnosis and medical decisions because of the complexity of the human biological system and the high possibility of false positive and false negative rates. The combination of multiple biomarkers could include highly discriminatory nucleic acids (Cagir et al., 1999), proteins (Behnisch et al., 2001, Srinivas et al., 2002) and small molecules such as metabolites (Behnisch et al., 2001). However, to date no technology has been reported addressing the multiplexing mode including the measurement of RNA, protein and small molecules.

Recently, a study conducted in our laboratory reported an electrochemical (EC) sensor for oral cancer detection based on the simultaneous detection of two salivary biomarkers: interleukin (IL)-8 mRNA and IL-8 protein (Wei et al., 2009). Thereby, the limit of detection of salivary IL-8 RNA reached to 3.9 fM in saliva while the limit of detection for IL-8 protein was 7.4 pg/mL in saliva. Applying the IL-8 multiplex assay in 28 cancer and 28 matched controls showed a significant clinical discrimination with a 90% sensitivity and specificity for both markers. Measuring both markers simultaneously, showed a better accuracy than individually indicating that EC sensor is not only an alternative method to PCR/ELISA, but also it provides fast, effective and accurate multiplexing measurements for real clinical diagnostics. This report is the first to show multiplexing detection of RNA and protein salivary biomarkers and based on this data the EC sensor promises to be a promising miniaturization system with a high clinical application impact.

Outlook

Translating scientific findings of nucleic acids, proteins and metabolites in body fluids to clinical applications is a cumbersome and challenging journey. Rarely, has the final destination of the clinical implementation of a test been reached. In order to utilize disease detection biomarkers, it is of utmost importance to understand the basic mechanisms (e.g. exosomes) underlying the rationale of salivary biomarkers. Our group continues to pursue the biology of salivary analytes and the development of technologies in order to detect distinct biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity to achieve compliance for the clinical setting at the FDA level. We are convinced that our efforts in salivary diagnostics will ultimately result in the detection of diseases, including cancer, optimally at the premalignant stage, supporting the management of cancerous diseases by enhancing the survival rate. Moreover, the avenue of saliva diagnostics incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic findings will enable us to connect molecular analytes to monitor therapies, therapeutic outcomes, and finally disease progression in cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/NIH grants U01 DE016275 and U01DE17790.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Both authors claim that there is no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

Literature

- Adam DJ, Milne AA, Evans SM, Roulston JE, Lee AJ, Ruckley CV, Bradbury AW. Serum amylase isoenzymes in patients undergoing operation for ruptured and non-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:229–35. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamski M, Blackwell T, Menon R, Martens L, Hermjakob H, Taylor C, Omenn GS, States DJ. Data management and preliminary data analysis in the pilot phase of the HUPO Plasma Proteome Project. Proteomics. 2005;5:3246–61. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A, Ric de Vos CH, Verhoeven HA, Maliepaard CA, Kruppa G, Bino R, Goodenowe DB. Nontargeted metabolome analysis by use of Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Mass Spectrometry. OMICS. 2002;6:217–34. doi: 10.1089/15362310260256882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai J, Smith B, David WT. Saliva Ontology: an ontology-based framework for a Salivaomics Knowledge Base. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alevizos I, Mahadevappa M, Zhang X, Ohyama H, Kohno Y, Posner M, Gallagher GT, Varvares M, Cohen D, Kim D, Kent R, Donoff RB, Todd R, Yung CM, Warrington JA, Wong DT. Oral cancer in vivo gene expression profiling assisted by laser capture microdissection and microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2001;20:6196–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughan LW, Robertello FJ, Sarrett DC, Denny PA, Denny PC. Salivary mucin as related to oral Streptococcus mutans in elderly people. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15:10–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2000.150102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnisch PA, Hosoe K, Sakai S. Bioanalytical screening methods for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds a review of bioassay/biomarker technology. Environ Int. 2001;27:413–39. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle JO, Mao L, Brennan JA, Koch WM, Eisele DW, Saunders JR, Sidransky D. Gene mutations in saliva as molecular markers for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Surg. 1994;168:429–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman BM, Wong DT. Disease mechanism and biomarkers of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18:228–33. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000219250.15041.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagir B, Gelmann A, Park J, Fava T, Tankelevitch A, Bittner EW, Weaver EJ, Palazzo JP, Weinberg D, Fry RD, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclase C messenger RNA is a biomarker for recurrent stage II colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:805–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai RL, Grandis JR. Advances in molecular diagnostics and therapeutics in head and neck cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2006;7:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s11864-006-0027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaita TM, Graham SM, Maxwell SM, Sirivasin W, Sabchareon A, Beeching NJ. Salivary sampling for hepatitis B surface antigen carriage: a sensitive technique suitable for epidemiological studies. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995;15:135–9. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1995.11747761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E. Integrating Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Drug Discovery & Development. 2006 Drug Discovery & Development. [Google Scholar]

- Denny P, Hagen FK, Hardt M, Liao L, Yan W, Arellanno M, Bassilian S, Bedi GS, Boontheung P, Cociorva D, Delahunty CM, Denny T, Dunsmore J, Faull KF, Gilligan J, Gonzalez-Begne M, Halgand F, Hall SC, Han X, Henson B, Hewel J, Hu S, Jeffrey S, Jiang J, Loo JA, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Malamud D, Melvin JE, Miroshnychenko O, Navazesh M, Niles R, Park SK, Prakobphol A, Ramachandran P, Richert M, Robinson S, Sondej M, Souda P, Sullivan MA, Takashima J, Than S, Wang J, Whitelegge JP, Witkowska HE, Wolinsky L, Xie Y, Xu T, Yu W, Ytterberg J, Wong DT, Yates JR, 3rd, Fisher SJ. The proteomes of human parotid and submandibular/sublingual gland salivas collected as the ductal secretions. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1994–2006. doi: 10.1021/pr700764j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer K, Hammock BD. Metabolomics--a new exciting field within the “omics” sciences. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:A396–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-1241997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry and protein analysis. Science. 2006;312:212–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1124619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobitch RK, Svensson CK. Therapeutic drug monitoring in saliva. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;23:365–79. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199223050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Medany OM, El-Din Abdel Wahab KS, Abu Shady EA, Gad El-Hak N. Chronic liver disease and hepatitis C virus in Egyptian patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1895–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons W. Accuracy of oral specimen testing for human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med. 1997;102:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiehn O, Kopka J, Dormann P, Altmann T, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L. Metabolite profiling for plant functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1157–61. doi: 10.1038/81137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Zhou H, Zhang L, Lee JW, Zhou Q, Hu S, Wolinsky LE, Farrell J, Eibl G, Wong DT. Systemic disease-induced salivary biomarker profiles in mouse models of melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes MA, Rodrigues FH, Afonso-Cardoso SR, Buso AM, Silva AG, Favoreto S, Jr, Souza MA. Levels of immunoglobulin A1 and messenger RNA for interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha in total saliva from patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 with chronic periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:177–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormally E, Vineis P, Matullo G, Veglia F, Caboux E, Le Roux E, Peluso M, Garte S, Guarrera S, Munnia A, Airoldi L, Autrup H, Malaveille C, Dunning A, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Lund E, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Palli D, Krogh V, Tumino R, Panico S, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Pera G, Martinez C, Dorronsoro M, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Quiros JR, Hallmans G, Day NE, Key TJ, Saracci R, Kaaks R, Riboli E, Hainaut P. TP53 and KRAS2 mutations in plasma DNA of healthy subjects and subsequent cancer occurrence: a prospective study. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6871–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans H, Slack FJ. Micro-RNAs: small is plentiful. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:17–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Rudnick PA, Wang W, Lee CS, Devoe DL, Balgley BM. Characterization of the human salivary proteome by capillary isoelectric focusing/nanoreversed-phase liquid chromatography coupled with ESI-tandem MS. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1469–78. doi: 10.1021/pr060065m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel R, Hanecke P. The application of saliva, sweat and tear fluid for diagnostic purposes. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1993;51:903–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst EJ, Oppenheim FG. Saliva: a dynamic proteome. J Dent Res. 2007;86:680–93. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr AE, Hatch AV, Throckmorton DJ, Tran HM, Brennan JS, Giannobile WV, Singh AK. Microfluidic immunoassays as rapid saliva-based clinical diagnostics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607254104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz C, Chevalier F, Centeno D, Rofidal V, Egea JC, Rossignol M, Sommerer N, Deville de Periere D. MS characterization of multiple forms of alpha-amylase in human saliva. Proteomics. 2005;5:4597–607. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Arellano M, Boontheung P, Wang J, Zhou H, Jiang J, Elashoff D, Wei R, Loo JA, Wong DT. Salivary proteomics for oral cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Cancer Res. 2008a;14:6246–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Loo JA, Wong DT. Human body fluid proteome analysis. Proteomics. 2006;6:6326–53. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Loo JA, Wong DT. Human saliva proteome analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007a;1098:323–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Wang J, Meijer J, Ieong S, Xie Y, Yu T, Zhou H, Henry S, Vissink A, Pijpe J, Kallenberg C, Elashoff D, Loo JA, Wong DT. Salivary proteomic and genomic biomarkers for primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007b;56:3588–600. doi: 10.1002/art.22954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Xie Y, Ramachandran P, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Li Y, Loo JA, Wong DT. Large-scale identification of proteins in human salivary proteome by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis-mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2005;5:1714–28. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Yen Y, Ann D, Wong DT. Implications of salivary proteomics in drug discovery and development: a focus on cancer drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007c;12:911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Yu T, Xie Y, Yang Y, Li Y, Zhou X, Tsung S, Loo RR, Loo JR, Wong DT. Discovery of oral fluid biomarkers for human oral cancer by mass spectrometry. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2007d;4:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Zhou M, Jiang J, Wang J, Elashoff D, Gorr S, Michie SA, Spijkervet FK, Bootsma H, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A, Horvath S, Wong DT. Systems biology analysis of Sjogren's syndrome and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in parotid glands. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:81–92. doi: 10.1002/art.24150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Zimmermann BG, Zhou H, Wang J, Henson BS, Yu W, Elashoff D, Krupp G, Wong DT. Exon-level expression profiling: a comprehensive transcriptome analysis of oral fluids. Clin Chem. 2008b;54:824–32. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.096164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusko WJ, Milsap RL. Pharmacokinetic principles of drug distribution in saliva. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:36–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juusola J, Ballantyne J. Messenger RNA profiling: a prototype method to supplant conventional methods for body fluid identification. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;135:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas M, Hillenkamp F. Laser desorption ionization of proteins with molecular masses exceeding 10,000 daltons. Anal Chem. 1988;60:2299–301. doi: 10.1021/ac00171a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper D. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. © 2008 McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Cho YE, Kim YW, Kim JY, Lee S, Park JH. Suppression of putative tumour suppressor gene GLTSCR2 expression in human glioblastomas. J Pathol. 2008;216:218–24. doi: 10.1002/path.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornman KS, Crane A, Wang HY, di Giovine FS, Newman MG, Pirk FW, Wilson TG, Jr, Higginbottom FL, Duff GW. The interleukin-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kountoruras J. Diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1998;42:900–901. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.899c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristal B, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Beal MF, Marson WR. Brain Energetics. Integration of Molecular and Cellular Processes. In: Springer, editor. handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology. New York: 2007. pp. 889–912. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Wong DT. Saliva: an emerging biofluid for early detection of diseases. Am J Dent. 2009;22:241–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendenmann U, Grogan J, Oppenheim FG. Saliva and dental pellicle--a review. Adv Dent Res. 2000;14:22–8. doi: 10.1177/08959374000140010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Elashoff D, Oh M, Sinha U, St John MA, Zhou X, Abemayor E, Wong DT. Serum circulating human mRNA profiling and its utility for oral cancer detection. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1754–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, St John MA, Zhou X, Kim Y, Sinha U, Jordan RC, Eisele D, Abemayor E, Elashoff D, Park NH, Wong DT. Salivary transcriptome diagnostics for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2004a;10:8442–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhou X, St John MA, Wong DT. RNA profiling of cell-free saliva using microarray technology. J Dent Res. 2004b;83:199–203. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisacek F, Cohen-Boulakia S, Appel RD. Proteome informatics II: bioinformatics for comparative proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:5445–66. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo JA, Yan W, Ramachandran P, Wong DT. Comparative Human Salivary and Plasma Proteomes. J Dent Res. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0022034510380414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, Horvitz HR, Golub TR. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Okahara F, Kanaho Y. The tumour suppressor PTEN: involvement of a tumour suppressor candidate protein in PTEN turnover. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:343–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0320343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamud D. Oral diagnostic testing for detecting human immunodeficiency virus-1 antibodies: a technology whose time has come. Am J Med. 1997;102:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel ID. The functions of saliva. J Dent Res. 1987;66 Spec No:623–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660S203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael A, Bajracharya SD, Yuen PS, Zhou H, Star RA, Illei GG, Alevizos I. Exosomes from human saliva as a source of microRNA biomarkers. Oral Dis. 2010;16:34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer C, Gharehbaghi-Schnell E, Korschineck I. Messenger RNA profiling: a novel method for body fluid identification by real-time PCR. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;157:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochnio JJ, Scheifele DW, Ho M, Mitchell LA. New, ultrasensitive enzyme immunoassay for detecting vaccine- and disease-induced hepatitis A virus-specific immunoglobulin G in saliva. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:98–101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.98-101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okahara F, Ikawa H, Kanaho Y, Maehama T. Regulation of PTEN phosphorylation and stability by a tumor suppressor candidate protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45300–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenn GS. Exploring the human plasma proteome. Proteomics. 2005;5:3223–3225. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200590056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenn GS, States DJ, Adamski M, Blackwell TW, Menon R, Hermjakob H, Apweiler R, Haab BB, Simpson RJ, Eddes JS, Kapp EA, Moritz RL, Chan DW, Rai AJ, Admon A, Aebersold R, Eng J, Hancock WS, Hefta SA, Meyer H, Paik YK, Yoo JS, Ping P, Pounds J, Adkins J, Qian X, Wang R, Wasinger V, Wu CY, Zhao X, Zeng R, Archakov A, Tsugita A, Beer I, Pandey A, Pisano M, Andrews P, Tammen H, Speicher DW, Hanash SM. Overview of the HUPO Plasma Proteome Project: results from the pilot phase with 35 collaborating laboratories and multiple analytical groups, generating a core dataset of 3020 proteins and a publicly-available database. Proteomics. 2005;5:3226–45. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy V, Sharma S, Deshpande A, Zhou H, Gimzewski J, Wong DT. Nanostructural and transcriptomic analyses of human saliva derived exosomes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NJ, Li Y, Yu T, Brinkman BM, Wong DT. Characterization of RNA in saliva. Clin Chem. 2006;52:988–94. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Henson BS, Kastratovic DA, Abemayor E, Wong DT. Salivary microRNA: discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5473–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NJ, Zhou X, Yu T, Brinkman BM, Zimmermann BG, Palanisamy V, Wong DT. Characterization of salivary RNA by cDNA library analysis. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet NP, Bey P. Pharmacogenomics: challenges and opportunities. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6:495–498. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo F, Tenorio A. Detection and typing of lymphotropic herpesviruses by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1999;79:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran P, Boontheung P, Xie Y, Sondej M, Wong DT, Loo JA. Identification of N-linked glycoproteins in human saliva by glycoprotein capture and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1493–503. doi: 10.1021/pr050492k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PV, Reddy AP, Lu X, Dasari S, Krishnaprasad A, Biggs E, Roberts CT, Nagalla SR. Proteomic identification of salivary biomarkers of type-2 diabetes. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:239–45. doi: 10.1021/pr8003776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, Ratajczak MZ. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20:847–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehak NN, Cecco SA, Csako G. Biochemical composition and electrolyte balance of “unstimulated” whole human saliva. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:335–43. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sashikumar R, Kannan R. Salivary glucose levels and oral candidal carriage in type II diabetics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:706–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Sena-Esteves M, Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Tachibana I, Pohl U, Lee HK, Thanarajasingam U, Portier BP, Ueki K, Ramaswamy S, Billings SJ, Mohrenweiser HW, Louis DN, Jenkins RB. A transcript map of the chromosome 19q-arm glioma tumor suppressor region. Genomics. 2000;64:44–50. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Duff GW. Microbiological parameters associated with IL-1 gene polymorphisms in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:810–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027011810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas PR, Verma M, Zhao Y, Srivastava S. Proteomics for cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1160–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John MA, Li Y, Zhou X, Denny P, Ho CM, Montemagno C, Shi W, Qi F, Wu B, Sinha U, Jordan R, Wolinsky L, Park NH, Liu H, Abemayor E, Wong DT. Interleukin 6 and interleukin 8 as potential biomarkers for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:929–35. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.8.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler BM, Ruohola-Baker H. Small RNAs: keeping stem cells in line. Cell. 2008;132:563–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- States DJ, Omenn GS, Blackwell TW, Fermin D, Eng J, Speicher DW, Hanash SM. Challenges in deriving high-confidence protein identifications from data gathered by a HUPO plasma proteome collaborative study. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:333–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streckfus C, Bigler L, Navazesh M, Al-Hashimi I. Cytokine concentrations in stimulated whole saliva among patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome, secondary Sjogren's syndrome, and patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome receiving varying doses of interferon for symptomatic treatment of the condition: a preliminary study. Clin Oral Investig. 2001;5:133–5. doi: 10.1007/s007840100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto M, Wong DT, Hirayama A, Soga T, Tomita M. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry-based saliva metabolomics identified oral, breast and pancreatic cancer-specific profiles. Metabolomics. 2010;6:78–95. doi: 10.1007/s11306-009-0178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Baltimore D. MicroRNAs and immunity: tiny players in a big field. Immunity. 2007;26:133–7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesell ES, Page JG. Genetic control of drug levels in man: antipyrine. Science. 1968a;161:72–3. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3836.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesell ES, Page JG. Genetic control of drug levels in man: phenylbutazone. Science. 1968b;159:1479–80. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3822.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt DR, Blicharz TM, Hayman RB, Rissin DM, Bowden M, Siqueira WL, Helmerhorst EJ, Grand-Pierre N, Oppenheim FG, Bhatia JS, Little FF, Brody JS. Microsensor arrays for saliva diagnostics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098:389–400. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz A, Stuhler K, Wattenberg A, Hawranke E, Meyer HE, Schmalz G, Bluggel M, Ruhl S. Proteome analysis of glandular parotid and submandibular-sublingual saliva in comparison to whole human saliva by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2006;6:1631–9. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Pharmacogenomics: a systems approach. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2009;2:3–22. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Patel P, Liao W, Chaudhry K, Zhang L, Arellano-Garcia M, Hu S, Elashoff D, Zhou H, Shukla S, Shah F, Ho CM, Wong DT. Electrochemical sensor for multiplex biomarkers detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4446–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmarth PA, Riviere MA, Rustvold DL, Lauten JD, Madden TE, David LL. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography study of the human whole saliva proteome. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:1017–23. doi: 10.1021/pr049911o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ. Evaluating preparative isoelectric focusing of complex peptide mixtures for tandem mass spectrometry-based proteomics: a case study in profiling chromatin-enriched subcellular fractions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Anal Chem. 2005a;77:3198–207. doi: 10.1021/ac0482256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Rhodus NL, Griffin RJ, Carlis JV, Griffin TJ. A catalogue of human saliva proteins identified by free flow electrophoresis-based peptide separation and tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005b;4:1826–30. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D500008-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Apweiler R, Balgley BM, Boontheung P, Bundy JL, Cargile BJ, Cole S, Fang X, Gonzalez-Begne M, Griffin TJ, Hagen F, Hu S, Wolinsky LE, Lee CS, Malamud D, Melvin JE, Menon R, Mueller M, Qiao R, Rhodus NL, Sevinsky JR, States D, Stephenson JL, Than S, Yates JR, Yu W, Xie H, Xie Y, Omenn GS, Loo JA, Wong DT. Systematic comparison of the human saliva and plasma proteomes. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:116–134. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JR, Cociorva D, Liao L, Zabrouskov V. Performance of a linear ion trap-Orbitrap hybrid for peptide analysis. Anal Chem. 2006;78:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ac0514624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelles T, Purushotham KR, Macauley SP, Oxford GE, Humphreys-Beher MG. Saliva and growth factors: the fountain of youth resides in us all. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1826–32. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y. Principles of micro-RNA production and maturation. Oncogene. 2006;25:6156–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Farrell JJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Akin D, Park NH, Chia D, Wong DT. Salivary transcriptomic biomarkers for detection of resectable pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:949–57. e1–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann BG, Wong DT. Salivary mRNA targets for cancer diagnostics. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]