Cycloaddition reactions of nitrones,i azides,ii and related 1,3-dipolar species iii have become recognized as powerful tools for the construction of compounds with great utility in organic synthesis, chemical biology, and materials science. The conceptual model that underpins our understanding of this broad class of reactions was first formalized by Huisgen in 1963. iv This seminal contribution to organic chemistry provided chemists with a unified framework for understanding the structure and reactivity of 1,3-dipolar compounds, and also predicted the structures of several elementary 1,3-dipoles that were unknown at the time. Subsequent research has identified cycloaddition reactions of many of these predicted 1,3-dipolar species.v However, carbonyl imines (e.g., 3, Scheme 1) have remained elusive in the half-century since Huisgen’s initial prediction. Although these unusual dipoles have been postulated to be intermediates in the photochemical decomposition of nitroarenes,vi no compounds resulting from dipolar cycloadditions of carbonyl imines have previously been reported. In this communication, we demonstrate that carbonyl imines can be efficiently generated by Lewis acid-catalyzed rearrangement of N-sulfonyl oxaziridines and trapped by cycloaddition with a variety of dipolarophiles.

Scheme 1.

Lewis acid-dependent formation of nitrones or carbonyl imines from N-sulfonyl oxaziridines. Ns = 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl.

We recently reported that TiCl4-catalyzed rearrangement of N-sulfonyl oxaziridinesvii (“Davis oxaziridines”, e.g., 1) produces a new class of electron-deficient N-sulfonyl nitrones (2).viii These highly unstable nitrones can be efficiently intercepted in situ by cycloaddition with a variety of styrenic olefins, affording 1,2-isoxazolidines with very high levels of cis selectivity (5, Table 1, entry 1). In the course of investigations probing this novel reactivity, we made the surprising observation that a variety of other Lewis acid catalysts (entries 2–5) produce a side product that we identified as the regioisomeric and diastereomeric 1,2-isoxazolidine 4.ix The production of 4 suggested that Lewis acid-catalyzed rearrangement of 1 could generate either N-sulfonyl nitrones or N-sulfonyl carbonyl imines, and that the partitioning between these two 1,3-dipoles could be controlled by the identity of the catalyst. Intrigued by this observation, we initiated an investigation to develop conditions that would result in exclusive formation of carbonyl imine cycloadduct 4, which would enable us to explore this reactivity in greater detail.

Table 1.

Optimization of Lewis acid for carbonyl imine cycloaddition.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | T | yield[b] | 4:5 |

| 1[c] | TiCl4 | 23 °C | 69% | 1:>10 |

| 2 | BF3•OEt2 | 23 °C | 32% | 1:5 |

| 3 | Sc(OTf)3 | 23 °C | 65% | 1:2 |

| 4 | Yb(OTf)3 | 23 °C | 40% | 8:1 |

| 5 | La(OTf)3 | 23 °C | 26% | 9:1 |

| 6 | Sc(OTf)3•6 | 23 °C | 30% | >10:1 |

| 7 | Sc(OTf)3•7 | 23 °C | 38% | >10:1 |

| 8 | ScCl2(SbF6)•7 | 23 °C | 41% | >10:1 |

| 9 | ScCl2(SbF6)•7 | 40 °C | 80% | >10:1 |

Reactions conducted using 10 mol% of catalyst and 4 equiv of oxaziridine unless otherwise noted.

Yields and product ratios were determined by 1H NMR analysis using a calibrated internal standard.

Reaction conducted using 2 equiv of oxaziridine.

Noting that the larger lanthanide triflate Lewis acids favored formation of 4, albeit in poor yields, we speculated that coordination of a bulky ligand to a more reactive but poorly selective transition metal salt (e.g., Sc(OTf)3, entry 3) might reverse the selectivity. Indeed, coordination of either bipyridyl ligand 6 or bis(oxazoline) ligand (tmbox, 7)x results in exclusive formation of carbonyl imine cycloadduct 4, although the reactivity of these complexes is attenuated (entries 6 and 7). The cationic (tmbox)ScCl2(SbF6) complex proved to be a more reactive catalyst (entry 8)xi and at elevated temperatures affords good yields of the desired cycloadduct without loss of selectivity (entry 9). These selective, high-yielding conditions for formation of 4 were used to further investigate this novel rearrangement–cycloaddition sequence.

Both theoretical and experimental evidence supports the intermediacy of carbonyl imine 3 in these reactions. The possibility that oxaziridines might rearrange to carbonyl imines was initially proposed in a series of computational studies reported by Rzepa.xii These studies characterized the oxaziridine-to-carbonyl imine rearrangement as a thermally allowed, conrotatory electrocyclic ring opening, and predicted that the presence of electron-withdrawing N-substituents would significantly stabilize and increase the lifetime of carbonyl imines (vide infra). Given this theoretical support, we felt that the production of N-nosyl carbonyl imine intermediate 3 was a reasonable explanation to account for the formation of 4.

Second, the intermediacy of a carbonyl imine is also supported by the stereospecificity of the cycloaddition (Scheme 2). The reaction of 1 with cis-β-deuterostyrene d-8 (96 atom % D)xiii affords isoxazolidine d-9 without any detectable loss of stereochemical fidelity of the deuterium label. This would be the result expected from a stereospecific syn addition of a carbonyl imine with the olefin in a concerted cycloaddition process.

Scheme 2.

Cycloaddition of deuterium-labelled styrene.

Finally, to distinguish between the proposed carbonyl imine mechanism (Scheme 3, Mechanism A) and an alternate mechanism involving direct nucleophilic attack of the dipolarophile upon the Lewis acid-activated oxaziridine (Mechanism B), we investigated the cycloaddition of enantioenriched oxaziridine 1*. xiv Cycloadditions using 1* of 55% ee afforded only racemic cycloadducts (eq 1), which is consistent with reaction via an achiral intermediate such as 3, and is not consistent with the stereospecific nucleophilic attack suggested by Mechanism B. We can also rule out the alternate possibility that this result arises from rapid Lewis acid catalyzed racemization of oxaziridine 1*; when the reaction is halted before completion, the remaining oxaziridine can be re-isolated in enantioenriched form, albeit with reduced ee, along with racemic cycloadduct (eq 2). This indicates that the rate of formation of racemic cycloadduct 9 is faster than the rate of racemization of 1*, which is not consistent with Mechanism B but is fully consistent with slow, reversible Lewis acid-catalyzed rearrangement of 1 to carbonyl imine 3 followed by rapid cycloaddition with styrene, as proposed in Mechanism A.

Scheme 3.

Stereochemical probe in support of carbonyl imine intermediate 3.

Table 2 summarizes the range of dipolarophiles that participate in the carbonyl imine cycloaddition.xv Styrenes are very good substrates for this process, and substitution at the para (entries 2–5), and meta (entries 6–8) positions have little impact on the efficiency of the reaction. On the other hand, large ortho substituents diminish the efficiency and diastereoselectivity of the reaction (entries 9–11), and styrenes bearing substitutents on the olefin do not undergo cycloaddition in synthetically useful yields (entry 12).

Table 2.

Dipolarophile scope in carbonyl imine cycloadditions.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | dipolarophile | product | yield[b,d] | trans:cis[c,d] |

|

||||

| 1 | Ar = Ph | 65% | >10:1 | |

| 2 | Ar = 4-AcOPh | 66% | >10:1 | |

| 3 | Ar = 4-ClPh | 74% | >10:1 | |

| 4 | Ar = 4-BrPh | 69% | >10:1 | |

| 5 | Ar = 4-MeO2CPh | 70% | >10:1 | |

| 6 | Ar = 3-MeOPh | 69% | >10:1 | |

| 7 | Ar = 3-FPh | 52% | >10:1 | |

| 8 | Ar = 3-ClPh | 55% | >10:1 | |

| 9 | Ar = 2-ClPh | 19%[e] | 7:1 | |

| 10 | Ar = 2-MePh | 56% | 9:1 | |

| 11 | Ar = 2-FPh | 62% | >10:1 | |

| 12 |  |

26% | >10:1 | |

|

||||

| 13 | R = n-Hex | 78% | >10:1 | |

| 14 | R = Bn | 68% | >10:1 | |

| 15 | R = cyclohexyl | 60% | >10:1 | |

| 16 | R = 1-adamantyl | 24%[e] | >10:1 | |

| 17 |  |

74% | >10:1 | |

| 18 |  |

79% | >10:1 | |

| 19 |  |

78% | >10:1 | |

| 20 |  |

65% | >10:1 | |

| 21 |  |

73% | >10:1 | |

| 22 |  |

72% | >10:1 | |

| 23 |  |

79% | >10:1 | |

| 24 |  |

73% | >10:1 | |

| 25 |  |

|

75% | 1:>10 |

| 26 |  |

85% | 4:1 | |

| 27 |  |

|

89% | 1:>10 |

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

Isolated yields unless otherwise noted.

Diastereomer ratios determined by 1H NMR analysis.

Yields and diastereomer ratios represent the averaged results of two reproducible experiments.

Yield determined by 1H NMR analysis using a calibrated internal standard.

Monosubstituted aliphatic alkenes are also excellent substrates for cycloaddition. Olefins bearing both linear and branched alkyl substituents react smoothly (entries 13–15), although tertiary alkyl substituents diminish the yield of the cycloadduct (entry 16). A variety of functional groups are easily tolerated, including ethers, halides, esters, silanes, and protected amines and alcohols (entries 17–22). Notably, despite the Lewis acidity of the cationic scandium(III) complex, the reaction conditions tolerate the presence of sensitive acetal functional groups (entry 23). We have found that internal aliphatic alkenes are unreactive using this methodology; thus, highly chemoselective cycloaddition of terminal olefins is observed in substrates bearing multiple olefinic bonds (entry 24).

The HOMO and LUMO energies of these highly electron-deficient carbonyl imines are presumably quite low and would be expected to be poorly matched to electron-deficient dipolarophiles. Indeed, fumarates, succinimides, and acrylates failed to produce the desired cycloadducts. On the other hand, heteroatom-containing dipolarophiles proved to be good substrates for cycloaddition. Aldehydes (entry 25), ketones (entry 26), and imines (entry 27) participated in this novel cycloaddition in good yields and with good diastereoselectivity.xvi

Although the scope of the dipolarophile is quite broad, the scope of the oxaziridine proved to be somewhat more limited (Table 3). Oxaziridines bearing aliphatic C-substituents do not participate in this reaction (entry 1), and the use of N-sulfonyl groups bearing electron-withdrawing substituents is critical to the success of the rearrangement-cycloaddition process (entries 2–4). This observation is fully consistent with Rzepa’s computation studies, which suggested that the introduction of electron-withdrawing N-substituents would significantly increase the propensity of the oxaziridine to rearrange to the isomeric carbonyl imine.xii A variety of C-aromatic N-nosyl oxaziridines are excellent carbonyl imine precursors. Experiments utilizing para or meta substituents proceeded smoothly (entries 6–8), although diminished yields are observed using ortho-substituted oxaziridines (entry 9). Electron-donating substituents increase the propensity of the oxaziridine to react; however, N-nosyl oxaziridines bearing even weakly electron-donating groups at the para position (e.g., methyl) are very unstable and can decompose violently.xvii

Table 3.

Variation of oxaziridine structure.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | oxaziridine | product | yield[b,d] | trans:cis[C,d] |

|

||||

| 1 | R = t-Bu | 0% | -- | |

| 2 | R = cyclopropyl | 0% | -- | |

|

|

|||

| 2 | Ar1 = Ph | 0% | -- | |

| 3 | Ar1 = 4-ClPh | 18% | >10:1 | |

| 4 | Ar1 = 4-CF3Ph | 45% | >10:1 | |

|

|

|||

| 6 | Ar2 = 4-FPh | 83% | >10:1 | |

| 7 | Ar2 = 3-MeOPh | 81% | >10:1 | |

| 8 | Ar2 = 3,5-Me2Ph | 90% | >10:1 | |

| 9 | Ar2 = 2-ClPh | 50% | 10:1 | |

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

Isolated yields unless otherwise noted.

Diastereomer ratios determined by 1H NMR analysis.

Yields and diastereomer ratios represent the averaged results of two reproducible experiments.

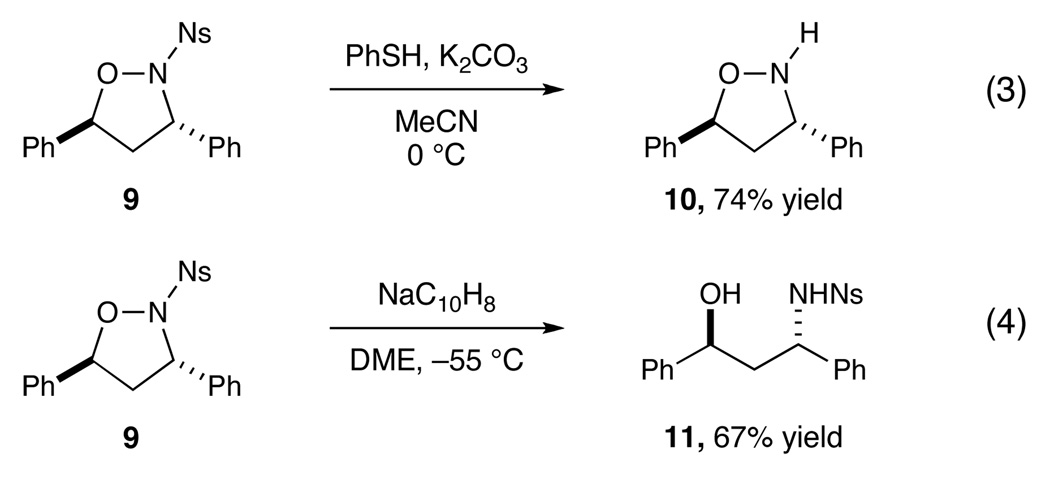

The superior reactivity of oxaziridines bearing electron-deficient N-sulfonyl groups confers an additional practical benefit to this methodology (Scheme 4). The N-nosyl moiety can be removed from trans-1,2-isoxazolidine cycloadduct 9 under the mild conditions developed by Fukuyama for this deprotection (PhSH, K2CO3);xviii no cleavage of the sensitive N–O bond is observed in the reaction, and the N-unsubstituted isoxazolidine 10 is isolated in good yields (eq 3). Alternatively, the heterocycle can be ringopened upon reduction of 9 with sodium naphthalenide, which affords N-nosyl-protected anti-1,3-aminoalcohol 11 in high diastereomeric purity (eq 4). Importantly, the isomeric cis-1,2-isoxazolidines resulting from our previously reported TiCl4-catalyzed nitrone cycloadditions are also amenable to these synthetic manipulations.viii Thus, using two complementary sets of conditions, the reaction between N-sulfonyl oxaziridines and olefins can provide access to cis- and trans-N-H-isoxazolidines and syn and anti 1,3-aminoalcohols with high levels of control over the chemoselectivity and stereoselectivity of the two-step process.

Scheme 4.

Conversion of N-isoxazolidines to N-H-isoxazolidines or 1,3-aminoalcohols under complementary conditions.

In summary, we have discovered that oxaziridines undergo highly stereoselective cycloaddition with a variety of dipolarophiles in the presence of a bulky scandium(III) catalyst. This reactivity suggests a carbonyl imine intermediate, and this study is the first report of cycloaddition products arising from this long-elusive class of 1,3-dipoles. As a method for the synthesis of structurally complex heterocycles, this transformation is a valuable complement to the TiCl-catalyzed nitrone cycloadditions previously reported by our laboratory. Thus, either cis or trans N-sulfonyl-1,2-isoxazolidines can be selectively produced from the combination of N-sulfonyl oxaziridines and olefins, and the sense of diastereoselectivity can be controlled by the choice of Lewis acid catalyst utilized. An enantioselective variant of these reactions would be a powerful tool for the synthesis of complex molecules. While we have not yet observed good levels of enantioinduction using a variety of chiral bis(oxazoline) ligands commonly used in asymmetric catalysisxix in place of 7, studies towards this goal are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin Williamson for the preparation of d-8. Financial support for this research has been provided by Abbott Laboratories (fellowship to K.M.P.), the NIH (R01-GM084022), and the NSF (CHE-0645447). The NMR spectroscopy facility at UW-Madison is funded by the NIH (S10 RR04981-01) and NSF (CHE-9629688).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Katherine M. Partridge, Department of Chemistry University of Wisconsin–Madison 1101 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706 (USA)

Tehshik P. Yoon, Department of Chemistry University of Wisconsin–Madison 1101 University Avenue, Madison, WI 53706 (USA).

References

- i.For reviews of nitrone cycloaddition chemistry, see: Revuelta J, Cicchi S, Goti A, Brandi A. Synthesis. 2007:485–504. Merino P. In: Science of Synthesis. Padwa A, editor. Vol. 27. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2004. pp. 511–580. Gothelf KV, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Commun. 2000:1449–1458. Frederickson M. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:403–425. Confalone PN, Huie EM. Org. React. 1988;36:1–173. Tufariello JJ, J J. In: 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. Padwa A, editor. Vol. 2. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1984. pp. 83–168. Black DS, Crozier RF, Davis VC. Synthesis. 1975:205–221.

- ii.For recent reviews of azide cycloaddition chemistry, see: Best MD. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6571–6584. doi: 10.1021/bi9007726. Meldal M, Tornøe CW. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952–3015. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. Tron GC, Pirali T, Billington RA, Canonico PL, Sorba G, Genazzani AA. Med. Res. Rev. 2008;28:278–308. doi: 10.1002/med.20107. Gil MV, Arévalo MJ, López Ó. Synthesis. 2007:1589–1620. Moses JE, Moorhouse AD. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1249–1262. doi: 10.1039/b613014n. Lutz J-F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1018–1025. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604050. Wu P, Fokin VV. Aldrichimica Acta. 2007;40:7–17. Binder WH, Kluger C. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006;10:1791–1815. Bock VD, Hiemstra H, Maarseveen JH. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:51–68.

- iii.For general reviews of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, see: Stanley LM, Sibi MP. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2887–2902. doi: 10.1021/cr078371m. Nair V, Suja TD. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:12247–12275. Pellissier H. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3235–3285. Molteni G. Heterocycles. 2006;68:2177–2202. Koumbis AE, Gallos JK. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:771–797. Koumbis AE, Gallos JK. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:585–628. Koumbis AE, Gallos JK. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:397–425. Padwa A, Pearson WH, editors. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry Toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. New York: Wiley; 2002. Karlsson S, Högberg H-E. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2001;33:105–172. Gothelf KV, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:863–909. doi: 10.1021/cr970324e.

- iv.a) Huisgen R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1963;2:633–696. [Google Scholar]; Huisgen R. Angew. Chem. 1963;75:742–754. [Google Scholar]; b) Huisgen R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1963;2:565–598. [Google Scholar]; Huisgen R. Angew. Chem. 1963;75:604–637. [Google Scholar]

- v.Azimines: Challand SR, Gait SF, Rance MJ, Rees CW, Storr RC. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1975;1:26–31. Gait SF, Rance MJ, Rees CW, Storr RC. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1972:688–689. Nitroso oxides: c) Ishikawa S, Nojima T, Sawaki Y. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1996;2:127–132. Ishikawa S, Tsuji S, Sawaki Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4282–4288.

- vi.Büchi G, Ayer DE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:689–690. [Google Scholar]

- vii.a) Davis FA. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8993–9003. doi: 10.1021/jo061027p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davis FA, Sheppard AC. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:5703–5742. [Google Scholar]; c) Davis FA, Jenkins R, Yocklovich SG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:5171–5174. [Google Scholar]

- viii.Partridge KM, Anzovino ME, Yoon TP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2920–2921. doi: 10.1021/ja711335d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ix.The structures of 4 and 5 were determined by X-ray crystallography. CCDC-751124 and CCDC-751123 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for 4 and 5, respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- x.a) Sulikowski GA, Lee S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:8035–8038. [Google Scholar]; b) Lee S, Lee W-M, Sulikowski GA. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:4224–4225. [Google Scholar]

- xi.a) Evans DA, Wu J, Masse CE, MacMillan DWC. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3379–3382. doi: 10.1021/ol026489d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Evans DA, Masse CE, Wu J. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3375–3378. doi: 10.1021/ol026488l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.a) Altmann JA, Rzepa HS. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1987;149:33–38. [Google Scholar]; b) Porter KE, Rzepa HS. J. Chem. Res. (S) 1983:262–263. [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Dolbier WR, Jr, Wicks GE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:3626–3631. [Google Scholar]

- xiv.Enantioenriched 1* was prepared by oxidation of the N-nosyl imine with (1S)-(+)-peroxycamphoric acid using the method of Torre: Bucciarelli M, Forni A, Moretti I, Torre G, Brückner S, Malpezzi L. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1988;2:1595–1598. Forni A, Moretti I, Torre G. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1987;2:699–704. Bucciarelli M, Forni A, Marcaccioli S, Moretti I, Torre G. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:187–192.

- xv.We found that the yields of these reactions became more reproducible upon addition of 20 mol% of NaSbF6. While the role of this additive is unclear, we speculate that it may help to control the aggregation state of the catalyst.

- xvi.The marked contrast between the good reactivity of heteroatom-containing dipolarophiles and the poor reactivity of other electron-deficient dipolarophiles suggests a change in mechanism for the cycloaddition. We propose a two-step process for imines and carbonyl compounds involving initial nucleophilic attack upon the dipole followed by ring closure. This mechanism would account for the difference in the stereochemical outcome of these reactions compared to cycloadditions involving olefinic dipolarophiles.

- xvii.Davis FA, Lamendola J, Jr, Nadir U, Kluger EW, Sedergran TC, Panunto TW, Billmers R, Jenkins R, Jr, Turchi IJ, Watson WH, Chen JS, Kimura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2000–2005. [Google Scholar]

- xviii.Fukuyama T, Jow C-K, Cheung M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6373–6374. [Google Scholar]

- xix.Desimoni G, Faita G, Jørgensen KA. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3561–3651. doi: 10.1021/cr0505324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.