Abstract

Background

Pluripotent stem cells represent one promising source for cellular cardiomyoplasty. In this study, we employed cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) to examine the ability of highly enriched cardiomyocytes (CMs) derived from murine embryonic stem cells (ESC) to form grafts and improve contractile function of infarcted rat hearts.

Methods and Results

Highly enriched ESC-CMs were obtained by inducing cardiac differentiation of ESCs stably expressing a cardiac restricted puromycin resistance gene. At the time of transplantation, enriched ESC-CMs expressed cardiac specific markers and markers of developing CMs but only 6% of them were proliferating. A growth factor containing vehicle solution or ESC-CMs (5–10 million) suspended in the same solution was injected into athymic rat hearts one week after myocardial infarction (MI). Initial infarct size was measured by CMR one day post-MI. Compared to vehicle, treatment with ESC-CMs improved global systolic function at 1 and 2-months post injection, and significantly increased contractile function in initially infarcted and border zones. Immunohistochemistry confirmed successful engraftment and the persistence of α-actinin positive ESC-CMs that also expressed α-smooth muscle actin. Connexin-43 positive sites were observed between grafted ESC-CMs but only rarely between grafted and host CMs. No teratomas were observed in any of the animals.

Conclusions

Highly enriched and early staged ESC-CMs were safe, formed stable grafts and mediated a long-term recovery of global and regional myocardial contractile function following infarction.

Keywords: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, embryonic stem cells, left ventricular remodeling, left ventricular wall motion, myocardial infarction

Restoration of contractile function to infarcted myocardium is the ultimate goal of cellular cardiomyoplasty. To achieve this goal, cell –based therapies have been proposed to replace some, or even a majority, of the myocytes lost to infarction. Several major unresolved issues remain, including the optimal cell type for effecting improvement of function, and the most useful method for assessment of contractile function.

Unlike most adult stem or progenitor cells, pluripotent stem cells derived from embryos (embryonic stem cells, ESCs) or experimentally from somatic cells (induced pluripotent stem cells, iPSCs) provide a nearly unlimited source of cardiomyocytes (CMs) for cellular cardiomyoplasty. However, constraints to the use of human-derived ESCs for cell therapy include ethical barriers and potential immunogenicity of ESC-progeny 1. These concerns can potentially be overcome by iPSCs, which are generated in vitro via transcription factor-mediated reprogramming, but suffer from interline heterogeneity and incomplete epigenetic remodeling 2–4. Because of this variability, ESCs still represent one of the best model systems to study critical issues in cellular cardiomyoplasty.

The adult myocardium, however, is not suited for guiding cardiac differentiation of ESCs in situ, and teratomas commonly form in immune-competent syngeneic hosts as well as immune-deficient hosts1,5. Alternatively, cardiac differentiation can be robustly induced in ESCs to derive bona fide CMs in vitro by formation of embryoid bodies (EBs) 6,7, but purification of CMs from a mixed cell population is challenging due to lack of suitable CM surface markers. In the past, CMs ranging from low to moderately high enrichment obtained from ESCs of murine and human origin were shown to form grafts and improve global function 8–14. In a mixed cell population, survival of CMs could be promoted by non-cardiac cells (e.g., fibroblasts) 15, but the risk of tumor formation from these non-cardiac cells poses a safety concern. In addition, regional myocardial contractile function was not directly characterized in these studies, which may add further insight into mechanisms of functional recovery. To overcome these latter two limitations, kinematic analysis of myocardial wall motion can be employed to estimate regional and intramural contractile function in a more detailed manner compared to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Importantly, these quantitative measurements have been achieved in both humans and mice 16–23. In our previous study, a significant improvement in LVEF and fractional shortening at infarct borders was observed after injection of undifferentiated ESCs, however, tagged MRI revealed a lack of contraction inside the graft, an observation consistent with infrequent cardiac differentiation in grafted cells 24. Hence, wall motion appears more specific to evaluate regional improvement of myocardial contraction 25,26.

Separately, we recently described murine ESCs containing a cardiac specific puromycin-resistant gene that eliminates non-cardiac cells by antibiotic treatment 27. By combining this system with CMR-based wall motion measurement, we have tested the hypotheses that highly enriched and early staged ESC-CMs can be isolated in large numbers for in vivo studies, and such ESC-CMs injected into athymic rats one week after surgical induction of myocardial infarction (MI) would form grafts and improve global and regional contractile function at 2-months post-MI as assessed by in vivo CMR.

Methods

1. Production of highly enriched ESC-CMs via a high throughput system

Murine R1 ESCs (clone syNP4) that stably express puromycin resistant gene cassette under the cardiac specific promoter of sodium calcium exchanger (NCX1) 27, were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells/ml into a spin flask (Integra Biosciences, Zizers, Switzerland) rotating at 60 rpm. Half of the ESC-media without LIF 24 was replaced every other day. BMP2 (0.5–1 ng/mL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added into media at day 6 after seeding. Puromycin (2.5 μg/mL) was added at day 9–10 when contracting EBs were first observed. EBs were then harvested and disassociated with collagenase on the following day. Monolayer culture continued for 7 days in the presence of puromycin and all surviving cells were harvested at day 16–17. This high throughput method routinely yielded 35(±15) million ESC-CMs in 16–17 days after initial seeding of 25 million.

2. Characterization of ESC-CMs

Enrichment The harvested cells were probed with antibody to cTnI (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and α-SMA (Biomeda, Foster, CA). The percentage of cTnI positive cells was estimated either by microscopy from a total of 4313 cells in 3 experiments, or, by florescence activated cell sorting (FACS) in 3 experiments, each examining 10,000 cell events.

Proliferation of ESC-CMs was evaluated by immunostaining for Ki-67 (Biomeda, Foster, CA). The number of Ki-67 and α-actinin double positive cells was counted by microscope from a total of 3932 α-actinin positive cells in 3 experiments to estimate the % of Ki-67+ population.

Gene expression profile Genes related to pluripotency: OCT3/4 and Nanog, and genes expressed at various stages of embryonic heart development: α- and β-myosin heavy chain (α- and β-MHC), myosin light chain 2v (MLC2V), NKX2.5, NCX1, atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) were examined. RNA from ESCs, 16–17 day old ESC-CMs and isolated adult rat CMs was extracted 27. The primer sequences and RT-PCR procedure were detailed in our previous report 28.

Cellular electrophysiology (EP) The whole-cell patch clamp configuration was used to record action potentials (APs) from ESC-CMs and adult mouse CMs using hard borosilicate micropipettes with a resistance from 2–3 MΩ 29. APs were initiated by current pulses (0.2–0.3 ms, 400–500 pA) and recorded at 25°C with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) under current clamp conditions. Pipette solution for recording APs contained (mmol/L): K-aspartate (80), KCl (50), MgCl2 (1), EGTA (10), HEPES (10), MgATP (3) with pH adjusted to 7.2. Bath solution contained (mmol/L): NaCl (140), KCl (5.4), CaCl2 (1.8), MgCl2 (1), HEPES (10) and glucose (10) with pH adjusted to 7.4.

3. Labeling with superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) particles

ESC-CMs were incubated with labeling media containing 6.25 μg Fe/mL (Feridex®, Berlex Laboratories) and 0.4 μg/mL of poly-L-Lysine overnight; labeling efficiency was determined24 from 3 experiments (total of 1490 cells).

4. In vivo Studies

Surgeries to induce MI and inject cells All animal procedures were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A reperfused MI was induced in female athymic nu/nu rats of 200 gram (Frederick Cancer Center, Frederick, MD)24. If the infarct size estimated by CMR was in the specified range (see below), the rat was assigned randomly to one of two groups: Vehicle (n=16) or ESC-CM (n=17), which received 100-μl Vehicle or 5–10 million ESC-CMs suspended in 100-μl Vehicle, respectively. The Vehicle solution contained a cocktail of growth factors13 dissolved in growth factor-reduced Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical, Bedford, MA). Intramyocardial injection was performed via a 2nd lateral thoracotomy 7 days post-MI. The lateral intercostal space was used as the entry site to avoid re-entry from the sternum. This strategy eliminated excessive bleeding from dissection of scar tissues formed after the 1st surgery and reduced surgery time & mortality. Vehicle or ESC-CM was injected into the mid-anterior LV wall in two locations.

CMR imaging and analysis CMR was performed on 4.7 Tesla horizontal bore Varian INOVA system equipped with a 12-cm ID gradient coil (25 Gauss/cm). A volume transmitting coil (ID of 70 mm) and a surface receiving coil (Insight MRI, MA) 24 were used. The animals were maintained under isoflurane (1% mixed with oxygen) via a nose cone; ECG and respiration were monitored and core temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.2°C (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). All images were acquired under cardiac and respiratory double gating. CMR scan took about 1 hour, which includes shimming and scout (15 min), cine (15 min) and displacement encoding with stimulated echo (DENSE) protocol (2 min/set × 5 sets × 3 slices = 30 min).

Initial infarct size was estimated 1-day post MI surgery by delayed hyper-enhancement (DHE) 24,30. Infarct size was calculated as percent of LV myocardial volume.

Confirmation of intramyocardial delivery of ESC-CMs was achieved by T2*-weighted CMR 1-day after injection 24.

Global function was measured at 1-day post MI, 1- and 2-months post cell injection; the LV from base to apex was covered by 11–13 contiguous short axis images (each 1 mm thick); LV end-diastolic (LVEDV) & end-systolic volume (LVESV), and LVEF were derived from cine images 21.

Regional contractile function was measured at 2-months post cell injection using a DENSE imaging sequence adapted from Kim et al 23. In our sequence, the read-out and phase-encoding directions were not swapped, and only one set of reference images was acquired. DENSE data sets were acquired from three SA slices (each 1-mm thick) from mid-ventricle to apex with a 1.5 mm gap using the following parameters: FOV = 40 × 40 mm2, matrix = 128 × 128, ke = 0.5 cycle/mm (0.156 cycle/pixel), 7 time points were captured evenly over 140 ms, which covers over 75% of the rat cardiac cycle (160–170 ms). The k-space raw data was analyzed offline using MATLAB program (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) as detailed in Supplemental Materials to derive intramyocardial displacements and normal Lagrangian strains (the radial strain, Err, and circumferential strain, Ecc).

Two segmentation schemes were used to present regional function: 1. I/B–L/B–S/R Scheme in which infarcted (I), lateral border (B–L) and septal border (B–S) of the infarcted area, and remote region (R) were defined on DHE images. These regions were then transferred to corresponding DENSE images to estimate the Ecc and Err. 2. S/A/L/P Scheme in which the myocardial wall on the DENSE image was divided into septum (S), anterior (A), lateral (L) and posterior (P) segments.

5. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) to characterize grafts and estimate scar size

All rats were euthanized at 2-months post-transplantation. The heart was embedded in paraffin or OCT. Each heart was cut in a short axis orientation (from base to the apex) into 30 levels with an interval of 300 μm between adjacent levels. Five sections (each 10 μm thick) per level were obtained for the following analyses: 1. H&E staining for general morphology and identification of teratoma; 2. Prussian blue (PB) staining to visualize SPIO labeled cells; 3. Immunofluorescence using primary antibodies against α-actinin, α-SMA and connexin-43 (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to visualize grafts; 4. Host macrophages identified by CD68 24; 5. Scar tissue was visualized by Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining on one section per level for all levels. The area of scar tissue and myocardium were measured in ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

5. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean (± standard deviation) in text and figures. Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. To test the hypothesis of intervention effects on global function at various time points, a three-stage linear model analysis, consisting of MANOVA, followed by ANOVA, followed by post hoc contrasts, was performed in SAS/STAT PROC GLM. In the first stage, a separate MANOVA was performed at 1-day post-MI, and at 1- and 2-months post cell injection. Each multivariate analysis included three within-subject cardiac outcomes, LVEF, LVESV, and LVEDV, and the three between-subject groups: ESC-CM, Vehicle, and Normal (non-infarcted). If the MANOVA was significant, by Wilks Lambda criterion, it was followed by a three-group, one-way ANOVA for each of the three cardiac outcomes. The third stage consisted of Tukey post hoc contrasts to identify significant intervention effects for each outcome at each time point.

Results

1. In vitro characterization of ESC-CMs

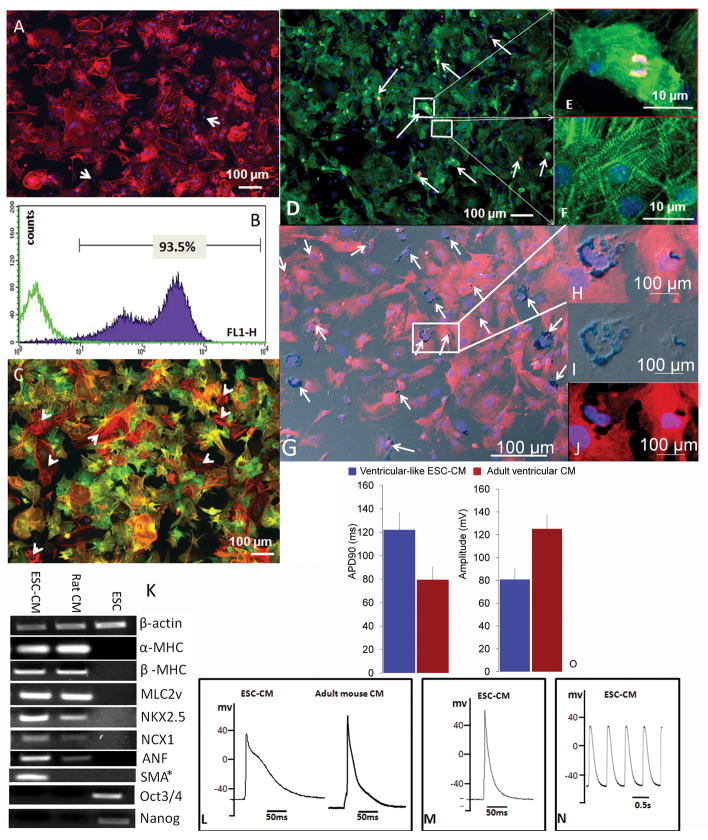

Immunostaining for cTnI suggested that cells harvested at the end of 16–17-day differentiation protocol were highly enriched in ESC-CM: the enrichment was 98 ± 1.7% by microscopy and 92 ± 3% by FACS (Fig 1A–B). About 98% of the cells were double positive for cTnI and α-SMA, and 2% are α-SMA positive only (arrow heads in Fig 1C). Gene expression profile suggested that ESC-CMs expressed mature cardiac markers including NCX1, α- and β-MHC and MLC2v as well as early markers such α-SMA (Fig 1K). Pluripotency markers were not expressed in ESC-CMs. Ki-67 and α-actinin double positive staining was observed in 5.7 ± 2.3% of α-actinin positive cells (Fig 1D, arrows). Ki-67 negative ESC-CMs showed typical striation patterns (Fig 1F), which were absent in positive ESC-CMs (Fig 1E). The SPIO labeling efficiency was 20.7 ± 9.8% (Fig 1G–J). Ventricle-, atria- and pacemaker-like cells were identified as subtypes of ESC-CM by single-cell EP studies (Fig 1L–N) and the percentages were similar to those previously published 27. Ventricle-like ESC-CMs exhibited a pronounced plateau phase with a longer APD90 but lower AP amplitude compared to adult ventricular myocytes (VM, Fig 1O), suggesting that they resembling embryonic/fetal rather than adult VM (Fig 1O).

Fig 1. Characterization of ESC-CMs in vitro.

A–B: Enrichment estimated by immunostaining for cTnI via fluorescence microscopy (A) or FACS (B). Arrows mark cTnI negative cells (A). Purple trace represents cTnI positive cells; green trace represents control cells, which were stained only with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (B).

C: Double staining for cTnI (green) and α-SMA (red).

D–F: Proliferation status assessed by double α-actinin (green) and Ki-67 (red) immunostaining. Boxes with magnified view in E and F show a Ki-67 positive and negative cell respectively.

G–J: G and H are the overlay of differential interference contrast (DIC) image of PB staining (I) and fluorescent α-actinin (J). SPIOs were shown surrounded by α-actinin (J). DIC conveys a greyish appearance in G–H. Nuclei in A–J were counterstained with DAPI.

K: Gene expression profile of ESC-CMs, ESCs, and adult rat ventricular CMs detected by RT-PCR. β-actin was used as reference. * H2O instead of rat CMs was used as a control in the middle well in PCR of SMA.

L–O: Electrophysiological properties. AP of ESC-CM of ventricle- (L), atria- (M) and pacemaker-like (N) cells. AP in L and M was evoked by current pulses. EP features of ventricle-like ESC-CM and adult VM (O). No statistics was performed for panel O due to small sample size in VM (n=3) and ESC-CM (n=2). APD90 = action potential duration at 90% repolarization.

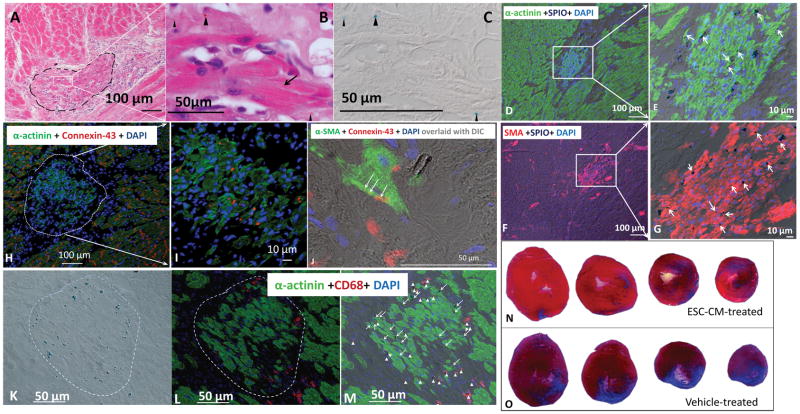

2. Characterization of ESC-CM grafts and estimation of final infarct size

Characterization of grafts SPIO-labeled ESC-CMs were injected into athymic hearts 1 week post MI, and no teratoma or teratoma-like structures were observed at 2-months post-injection in any of the injected hearts. Grafts were identified on H&E stained sections by morphology and confirmed by positive PB staining (Fig 2A–C). Grafted ESC-CMs were elongated and striated (Fig 2B). They were double positive for α-actinin and SPIOs (Fig 2D–E), and for α-SMA and SPIOs (Fig 2F–G) on adjacent sections. In host myocardium, α-SMA expression was limited to smooth muscle cells lining the vasculature (Fig 2F). Punctate connexin-43 positive sites were detected between host CMs and between grafted CMs (Fig 2H–I), but infrequently (although unequivocally) between the grafted (green) and host CM (Fig 2J).

Fig 2. Characterization of ESC-CM-formed grafts and estimation of final infarct size.

A: H&E staining shows a graft (dashed line) adjacent to the host myocardium. B: Grafted cells (arrow) are elongated and show clear striations. Brownish SPIO particles in cytoplasm (arrow heads) were confirmed by PB staining of the same section (arrow heads in C).

D–G: ESC-CM formed grafts were identified by double staining for SPIO and α-actinin (D–E), or by SPIO and α-SMA (F–G). Both host and grafted CM were positive for α-actinin; however, α-SMA was positive only in grafted ESC-CMs or in vascular smooth muscle in the host heart. Arrows mark α-actinin or SMA positive cells which contain SPIOs. D and F are adjacent sections.

H–I: Immunofluorescence of Connexin-43 (red) and α-actinin (green). Connexin-43 positive sites as punctated red dots or thin lines were frequently identified between host CMs (H) and between the grafted ES-CMs (I). J: Overlay of DIC image of PB staining with connexin-43 (red) and α-SMA (green). Connexin-43 positive sites (thin arrows) were found between a grafted CM (green) and host CM (its border revealed by DIC).

K–M: Evaluation of SPIO distribution. K: DIC image of PB staining for SPIO particles (blue spots). L: Immunofluorescence of α-actinin (green) and CD68 (red) for macrophages. M: Overlay of K and L revealed SPIO located in ESC-CMs (arrows) or in macrophages (arrow heads). The graft is outlined with the dashed lines. Nuclei in D–M were counterstained with DAPI.

N–O: Estimation of scar tissue by MT staining at 2-months post cell injection. Sections at the level of papillary muscle and at three adjacent levels toward the apex were displayed for an ESC-CM (N) and Vehicle -treated (O) heart.

Grafts were identified in ~70% ESC-CM treated rats (11 out of 17). The graft extended to 5–10 transverse levels; the graft area on sections ranged from 0.009 to 0.86 mm2, with an average of 0.14 mm2. The maximal graft volume was estimated to be 0.24% of LV volume with an average volume of 0.10 ± 0.086%.

Juxtaposition of SPIO-containing cell populations Triple staining for SPIO, α-actinin (or α-SMA) and CD68 (macrophage) revealed that 38±18% of PB positive cells were ESC-CMs and 62±18% were macrophages, which distributed around the graft (Fig 2K–M). No host CMs were PB positive. These data suggested that SPIOs were not uniquely associated with ESC-CMs; however, signals from SPIO could be used to localize grafts on histological sections and on MR images due to juxtaposition of the two SPIO-containing cell populations.

Estimation of final infarct size by MT staining of scar tissue at 2-months post injection (Fig 2N–O) revealed a substantially smaller scar tissue volume in ESC-CM vs. Vehicle group (5.9 ± 2.5% vs. 12.1 ± 5.0% of LV myocardial volume, P = 0.0481).

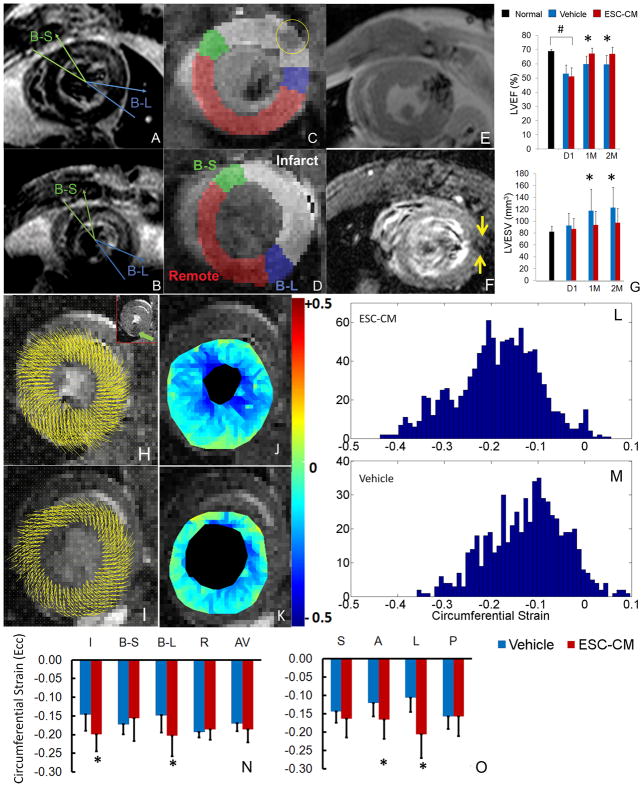

3. Initial infarct size, global and regional contractile function estimated by in vivo CMR

Initial infarct size was measured on DHE images (Fig 3A–B). Transmural infarct was observed in nearly every case and consistent with prolonged ligation time (45 min). The infarcted territory usually localized to the anterolateral portion of the myocardial wall and extended from mid-ventricle to apex. Animals with an infarct size in the range of [10% – 30%] of LV wall volume were assigned randomly to one of two experimental groups, whereas others were excluded. As a result, a relatively uniform distribution of infarct size in both groups was achieved: 20.4 ± 3.9% in ESC-CM (n=17) and 19.4 ± 4.9% in Vehicle group (n=16) without significant difference (P = 0.5). The initial infarcted, border and remote regions identified on DHE images were transferred to DENSE images (Fig 3C–D).

Fig 3. Initial infarct size, global and regional contractile function estimated by in vivo MRI.

A–B: Infarction visualized by DHE MRI at day-1 post MI from a heart in the ESC-CM (A) and Vehicle (B) group. For I/B–S/B–L/R segmentation: I was marked between the two arrows; B–S (between two green lines) and B–L (between two blue lines) were defined as 30° sectors neighboring the infarct segment, and R was the remaining myocardium16. The segmentation was transferred to DENSE images at the corresponding level (C–D): infarcted region is pseudo-colored in white, B–S in green, B–L in blue and R in red. The yellow circle in C identifies the SPIO-containing cells.

E–F: Visualization of SPIO containing cells at 1-day (E) and 2-months post cell injection (F, between arrows).

G: Global function of normal (non-infarcted), day-1 post MI, and 1- & 2-months post cell injection. #: P<0.05 for ESC-CM or Vehicle vs. normal at day-1. *: P<0.05 for ESC-CM vs. Vehicle group.

H–O: Displacement vectors overlaid on DENSE images (ED phase) of an ESC-CM (H) and Vehicle-treated heart (I); residual SPIO signal in a reference image is identified by a green arrow (inset of H); corresponding Ecc maps of the same hearts (J–K). Histograms of Ecc maps (L–M, y axis is number of triangular elements). Regional Ecc values plotted for ESC-CM and Vehicle groups based on I/B–S/B–L/R (N) or S/A/L/P Scheme (O). AV= average over all segments. *: P<0.05 for ESC-CM vs. Vehicle group.

SPIO-related MRI signal was sufficient at 1-day post-injection for assessing the distribution of injected cells (Fig 3E); At 2-months post injection, the hypointense signal was reduced but still traceable (Fig 3F and inset of 3H).

Global function LVEF in both groups was significantly depressed at day-1 post-MI compared to normal values (P < 0.0001, Fig 3G). Over time, LVEF in both groups increased suggesting that growth factors in the vehicle solution had a beneficial impact on post-MI remodeling. However, at both 1 and 2 months post-injection, the ESC-CM group achieved a significantly greater LVEF (P = 0.0003 and 0.0007, respectively) and lower LVESV (P = 0.0408 and 0.0411, respectively) than the Vehicle group. Taken together, these data demonstrate that ESC-CM mediated a significant improvement in global systolic function over that induced by soluble growth factors alone.

Regional contractile function Greater intramyocardial displacements were observed in ESC-CM vs. Vehicle-treated hearts (Fig 3H–I). Ecc maps and corresponding histograms revealed more vigorous contraction (i.e. more negative) in ESC-CM vs. Vehicle-treated hearts (Fig 3J–M). In I/B–S/B–L/R Scheme (Fig 3N), significantly greater Ecc in initial infarcted and B–L regions was observed in the ESC-CM vs. Vehicle group (P = 0.0328 and 0.0244, respectively). In the S/A/L/P Scheme (Fig 3O), Ecc in the anterior and lateral regions was greater in the ESC-CM than Vehicle group (P = 0.0481 and 0.0037, respectively). Results from both schemes are concordant, providing direct evidence that ESC-CMs mediated a substantial and regional improvement of myocardial contraction. The radial strain (Err) value for S/A/L/P Scheme is (0.25±0.09/0.29±0.09/0.30±0.09/0.31±0.12) for ESC-CM and (0.27±0.08/0.29±0.07/0.30±0.08/0.33±0.09) for Vehicle group, without statistically significant difference.

Discussion

Highly enriched ESC-CMs were obtained in large numbers. The degree of differentiation of ESC-CMs was determined by the following analyses: 1. double positive for cTnI and α-SMA (Fig 1C), 2. expression of Nkx2.5, NCX1, α- and β-MHC, MLC2v and α-SMA by RT-PCR (Fig 1K), 3. double positive for α-actinin and α-SMA 2-months after engraftment (Fig 2D–G). These data combined with the EP feature suggest a phenotype of early stage cardiomyocytes. On tissue sections (Fig 2F–G), SMA staining was clearly observed in SPIO labeled ESC-CMs, suggesting the usefulness of SMA marker for identifying grafted cells. Normally, α-SMA is expressed in smooth muscle cells or myofibroblasts, but in heart, it either marks the earliest appearance of embryonic CMs during heart development 31 or is a marker of dedifferentiation and hibernating myocardium 32,33. Since the ESC-CMs were positive for α-actinin, they were neither myofibroblasts 34 nor smooth muscle cells. These data therefore suggest the SMA marker may serve as a surrogate for surviving cells in the heart that do not readily mature or couple. Alternatively, the use of SMA as a marker of grafted cells could underestimate the coupling between grafted and host CM since a “mature” ESC-CM should have lost its SMA expression. This observation is important for two reasons: first, SMA can be used histologically as a marker to evaluate potentials of ESC-CM engraftment in the heart; and second, it can be used to identify conditions that may promote ESC-CM maturation in vivo (i.e., loss of SMA expression).

The ESC-CMs mediated teratoma-free myocardial repair by forming grafts, reducing scar size, and improving global and regional contractile function significantly over Vehicle-treated controls. The gap junction protein, connexin-43, was observed frequently between grafted ESC-CMs, but rarely between the grafted and host CMs (Fig 2J), suggesting that cellular coupling between grafts and host myocardium is far from optimal. Additional experiments will be required to address this question in the future with other ESC-CMs populations isolated at various developmental stages.

Our study did, however, clearly demonstrate the power of non-invasive, quantitative imaging to assess functional recovery following cellular cardiomyoplasty. First we addressed a critical shortcoming of many studies concerning large variations of infarct sizes following surgically-induced MI in rodents 35. Such variations may arise due to variability in rodent coronary artery anatomy and invisibility of the left anterior descending artery in a substantial portion of rats/mice, despite confirmation of myocardial ischemia upon ligation by ECG (e.g., ST elevation) and/or blanching of the affected region. Our approach of excluding subjects whose infarct size at day-1 was out of the specified range led to a relatively uniform distribution of infarct size in experimental groups, minimized the bias introduced by infarct size-related variations in post-MI remodeling, and allowed a therapeutic study to be completed with a reasonable group size (n ≤ 17).

Second, a more vigorous contraction in regions corresponding to initial infarcted and lateral border zones in ESC-CM treated animals suggests that relatively small grafts (<1% of LV volume) could mediate a substantial improvement in contractile function. Both the presence of grafts and a paracrine effect of ESC-CMs might have contributed to the improvement. Despite its small size, the graft might be able to transmit contractile force to the surrounding host CMs through proper coupling 15, or, it might reduce stiffness in the infarcted region 36. The grafted ESC-CMs might also mediate a paracrine effect by secretion of cytokines and growth factors, which might reduce apoptosis or autophagy of host CMs during post-MI remodeling. The significantly smaller scar size in the ESC-CM group (5.9% vs. 12.1% in Vehicle group) is consistent with this mechanism.

Third, by lowering the SPIO labeling efficiency (~ 20% cells were labeled), a mild perturbation of local magnetic field homogeneity was obtained at 2-months post-injection to avoid interference with DENSE protocol, while a sufficiently hypointense MRI signal was obtained at day-1 post injection to confirm intramyocardial delivery of cells. The close proximity of two SPIO-containing populations (grafted cells and macrophages) could be useful in that it provides clues as to localizing grafts. However, whether a SPIO-containing cell is an ESC-CM or a macrophage can only be established by histology. Hence, the SPIO-associated MRI signal itself may not represent a graft. In applications where biopsy is not an option, other methods (either a unique marker of grafted cells or an indirect method such as contractile function recovery in that region) will be required to confirm the existence of the graft.

In summary, highly enriched and early staged ESC-CMs engraft in the infarcted heart and significantly improve regional wall motion. CMR provides a powerful quantitative tool for assessment of cellular cardiomyoplasty and facilitates direct comparisons of functional improvements among scientific laboratories worldwide. These results together with our findings on SMA should foster improved strategies for cell-based therapies in heart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nan Zhou, MS, for programming in SAS/STAT to perform statistical analyses of LV global function.

Funding Sources

NIH grants R21EB-2473 and R01-HL081185 (RZ) and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging (KRB).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Nussbaum J, Minami E, Laflamme MA, Virag JAI, Ware CB, Masino A, Muskheli V, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Murry CE. Transplantation of undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells in the heart: teratoma formation and immune response. FASEB J. 2007;21:1345–1357. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6769com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, Cahan P, Kim J, Aryee MJ, Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Yabuuchi A, Takeuchi A, Cunniff KC, Hongguang H, McKinney-Freeman S, Naveiras O, Yoon TJ, Irizarry RA, Jung N, Seita J, Hanna J, Murakami P, Jaenisch R, Weissleder R, Orkin SH, Weissman IL, Feinberg AP, Daley GQ. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09342. Online publish ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin MH, Mason MJ, Xie W, Volinia S, Singer M, Peterson C, Ambartsumyan G, Aimiuwu O, Richter L, Zhang J, Khvorostov I, Ott V, Grunstein M, Lavon N, Benvenisty N, Croce CM, Clark AT, Baxter T, Pyle AD, Teitell MA, Pelegrini M, Plath K, Lowry WE. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swijnenburg R-J, Tanaka M, Vogel H, Baker J, Kofidis T, Gunawan F, Lebl DR, Caffarelli AD, de Bruin JL, Fedoseyeva EV, Robbins RC. Embryonic Stem Cell Immunogenicity Increases Upon Differentiation After Transplantation Into Ischemic Myocardium. Circulation. 2005;112:I-166–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doetschman TC, Eistetter H, Katz M, Schmidt W, Kemler R. The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985;87:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boheler KR, Czyz J, Tweedie D, Yang HT, Anisimov SV, Wobus AM. Differentiation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:189–201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000027865.61704.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min JY, Yang Y, Sullivan MF, Ke Q, Converso KL, Chen Y, Morgan JP, Xiao YF. Long-term improvement of cardiac function in rats after infarction by transplantation of embryonic stem cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:361–9. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ménard C, Hagège AA, Agbulut O, Barro M, Morichetti MC, Brasselet C, Bel A, Messas E, Bissery A, Bruneval P, Desnos M, Puceat M, Menasche P. Transplantation of cardiac-committed mouse embryonic stem cells to infarcted sheep myocardium: a preclinical study. The Lancet. 2005;366:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leor J, Gerecht S, Cohen S, Miller L, Holbova R, Ziskind A, Shachar M, Feinberg MS, Guetta E, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Human embryonic stem cell transplantation to repair the infarcted myocardium. Heart. 2007;93:1278–1284. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.093161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai W, Field LJ, Rubart M, Reuter S, Hale SL, Zweigerdt R, Graichen RE, Kay GL, Jyrala AJ, Colman A, Davidson BP, Pera M, Kloner RA. Survival and maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:504–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caspi O, Huber I, Kehat I, Habib M, Arbel G, Gepstein A, Yankelson L, Aronson D, Beyar R, Gepstein L. Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Improves Myocardial Performance in Infarcted Rat Hearts. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:1884–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O’Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Laake LW, Passier R, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL. Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes and Cardiac Repair in Rodents. Circ Res. 2008;102:1008–1010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolossov E, Bostani T, Roell W, Breitbach M, Pillekamp F, Nygren JM, Sasse P, Rubenchik O, Fries JWU, Wenzel D, Geisen C, Xia Y, Lu Z, Duan Y, Kettenhofen R, Jovinge S, Bloch W, Bohlen H, Welz A, Hescheler J, Jacobsen SE, Fleischmann BK. Engraftment of engineered ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes but not BM cells restores contractile function to the infarcted myocardium. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2315–2327. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Axel L, Dougherty L. MR imaging of motion with spatial modulation of magnetization. Radiology. 1989;171:841–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.3.2717762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young AA, Imai H, Chang CN, Axel L. Two-dimensional left ventricular deformation during systole using magnetic resonance imaging with spatial modulation of magnetization. Circulation. 1994;89:740–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.740. [erratum appears in Circulation 1994 Sep;90(3):1584] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1048–60. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1048::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aletras AH, Ding S, Balaban RS, Wen H. DENSE: displacement encoding with stimulated echoes in cardiac functional MRI. J Magn Reson. 1999;137:247–52. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein FH, Yang Z, Gilson WD, Berr SS, Kramer CM, French BA. MR tagging early after myocardial infarction in mice demonstrates contractile dysfunction in adjacent and remote regions. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:399–403. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou R, Pickup S, Glickson JD, Scott C, Ferrari VA. Assessment of Global and Regional Myocardial Function in the Mouse Using Cine- and Tagged MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;49:760–764. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Chen J, Ji S, Allen JS, Bayly PV, Wickline SA, Yu X. Harmonic phase MR tagging for direct quantification of Lagrangian strain in rat hearts after myocardial infarction. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1282–90. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial Tissue Tracking with Two-dimensional Cine Displacement-encoded MR Imaging: Development and Initial Evaluation. Radiology. 2004;230:862–871. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao H, Zhang H, Zheng Y, Ponde DE, Shen D, Gao F, Bakken AB, Schmitz A, Kung HF, Ferrari VA, Zhou R. Embryonic Stem Cell Grafting in Normal and Infarcted Myocardium: Serial Assessment with MR Imaging and PET Dual Detection. Radiology. 2009;250:821–829. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amado LC, Schuleri KH, Saliaris AP, Boyle AJ, Helm R, Oskouei B, Centola M, Eneboe V, Young R, Lima JA, Lardo AC, Heldman AW, Hare JM. Multimodality noninvasive imaging demonstrates in vivo cardiac regeneration after mesenchymal stem cell therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacquier A, Higgins CB, Martin AJ, Do L, Saloner D, Saeed M. Injection of Adeno-associated Viral Vector- Encoding Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene in Infarcted Swine Myocardium: MR Measurements of Left Ventricular Function and Strain. Radiology. 2007;245:196–205. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamanaka S, Zahanich I, Wersto RP, Boheler KR. Enhanced Proliferation of Monolayer Cultures of Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes Following Acute Loss of Retinoblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarasova Y, Riordon DKVT, Boheler K. In vitro Differentiation of mouse ES cells into muscle cells (Chapter 6. 130–1682) Embryonic Stem Cell. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D, Patel V, Zhou R, Levin M, Gao E, Ferrari VA, Lu M, Xu J, Zhang H, Hui Y, Cheng Y, Petrenko N, Yu Y, FitzGerald G. Cardiomyocyte cyclooxygenase-2 influences cardiac rhythm and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7548–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805806106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas D, Dumont C, Pickup S, Misselwitz B, Zhou R, Horowitz J, Ferrari VA. T1-weighted cine FLASH is superior to IR imaging of post-infarction myocardial viability at 4.7T. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:345–52. doi: 10.1080/10976640500451986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruzicka DL, Schwartz RJ. Sequential activation of alpha-actin genes during avian cardiogenesis: vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene transcripts mark the onset of cardiomyocyte differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2575–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dispersyn GD, Mesotten L, Meuris B, Maes A, Mortelmans L, Flameng W, Ramaekers F, Borgers M. Dissociation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and dedifferentiation in infarct border zones. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:849–57. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corradi D, Callegari S, Benussi S, Maestri R, Pastori P, Nascimbene S, Bosio S, Dorigo E, Grassani C, Rusconi R, Vettori MV, Alinovi R, Astorri E, Pappone C, Alfieri O. Myocyte changes and their left atrial distribution in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation related to mitral valve disease. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1080–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zlochiver S, Munoz V, Vikstrom KL, Taffet SM, Berenfeld O, Jalife J. Electrotonic Myofibroblast-to-Myocyte Coupling Increases Propensity to Reentrant Arrhythmias in Two-Dimensional Cardiac Monolayers. Biophysical Journal. 2008;95:4469–4480. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Acton PD, Thomas D, Zhou R. Quantitative imaging of myocardial infarct in rats with high resolution pinhole SPECT. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:429–434. doi: 10.1007/s10554-005-9046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berry MF, Engler AJ, Woo YJ, Pirolli TJ, Bish LT, Jayasankar V, Morine KJ, Gardner TJ, Discher DE, Sweeney HL. Mesenchymal stem cell injection after myocardial infarction improves myocardial compliance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2196–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.