Abstract

Individuals with social anxiety are prone to engage in post event processing (PEP), a post mortem review of a social interaction that focuses on negative elements. The extent that PEP is impacted by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and the relation between PEP and change during treatment has yet to be evaluated in a controlled study. The current study used multilevel modeling to determine if PEP decreased as a result of treatment and if PEP limits treatment response for two types of cognitive behavioral treatments, a group-based cognitive behavioral intervention and individually based virtual reality exposure. These hypotheses were evaluated using 91 participants diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. The findings suggested that PEP decreased as a result of treatment, and that social anxiety symptoms for individuals reporting greater levels of PEP improved at a slower rate than those with lower levels of PEP. Further research is needed to understand why PEP attenuates response to treatment.

Keywords: Post Event Processing, Treatment Outcome, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Social Anxiety

Post Event Processing (PEP) is a negatively valenced review of social situations in which inadequacies, mistakes, imperfections, and negative perceptions of the interaction are exaggerated and integrated into a larger history of poor social performance (Rachman, Grater-Andrew, & Shafran, 2000). PEP is included as a maintaining factor for social anxiety disorder in theoretical models of social anxiety (Clark & Wells, 1995; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), and empirical research has shown that PEP is associated with increased cognitive intrusions about social interactions, increased recall of past negative experiences, poorer concentration, and lowered anticipation for success in future social situations (Field, Psychol, & Morgan, 2004; Rachman, et al., 2000). There has been relatively little work examining PEP in a treatment context, and no controlled studies have examined whether PEP is impacted by treatment or impacts treatment response. The purpose of the current study is to determine whether or not PEP decreased as a result of cognitive behavioral therapy as compared to a waitlist comparison condition, and to examine the relation between PEP and treatment response for individual- and group-based therapies for social anxiety disorder.

The majority of research on PEP has examined its association with social anxiety (for a review see Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008). Empirical research with non-clinical (e.g. Dannahy & Stopa, 2007; Edwards, Rapee, & Franklin, 2003) and clinical samples (Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Coles, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Kocovski & Rector, 2008; Perini, Abbott, & Rapee, 2006) consistently supports a positive relation between PEP and social anxiety symptoms, with one exception (McEvoy & Kingsep, 2006). Furthermore, people with social anxiety disorder engage in more PEP than those without a clinical diagnosis (Mellings & Alden, 2000).

Only two studies have examined the relation between PEP and treatment outcome for CBT for social anxiety disorder. Abbott & Rapee (2004) examined change in PEP following 12 weeks of CBT that included exposure, attention training, assertiveness training, and realistic thinking (Abbott & Rapee, 2004). A pretest/posttest comparison suggested that PEP symptoms declined during the course of therapy. McEvoy and colleagues (2009) reported similar findings for a seven-week cognitive behavioral group therapy treatment. However, neither study included a control group, which makes it difficult to determine if PEP declined as a direct result of treatment or other effects. Thus, further research using a controlled design is warranted.

A second aim of the current study is to examine the impact of PEP on response to treatment. Work on this topic is necessary because not all individuals with social anxiety disorder benefit from CBT (Dalrymple & Herbert, 2007). Of those that do benefit, many remain with anxiety levels that are significantly higher than those without the disorder (Heimberg et al., 1998; Herbert et al., 2005). Little empirical research has examined factors that attenuate response to treatment, and PEP may be one such factor. McEvoy and colleagues’ (2009) work is suggestive of this relation, as these researchers demonstrated that change scores in PEP are correlated with change scores in social anxiety symptoms after treatment. Theoretical models also are suggestive that PEP may impact treatment response. According to Clark and Wells’ (1995) cognitive model of social anxiety, PEP serves to consolidate negative beliefs and to reduce attentional resources towards positive aspects of the social situation, thus rendering it difficult for the social phobic to disconfirm negative beliefs. Socially anxious individuals who engage in higher levels of PEP may find it more difficult to benefit from cognitive interventions. Additionally, research has shown that PEP occurs between exposure sessions and that PEP following the first session of therapy is positively related to state anxiety for the subsequent therapy session (Kocovski & Rector, 2008). Thus, from a learning perspective, PEP may attenuate response to treatment by maintaining high levels of anxiety between exposure therapy sessions when extinction learning is thought to occur (Rowe & Craske, 1998; Tsao & Craske, 2000). Although theoretical models and empirical research is suggestive, no studies to date have examined the extent that fluctuations in PEP relate to changes in social anxiety symptoms over the course of treatment.

The present study evaluated whether or not PEP decreased after individual and group CBT as compared to a waitlist control. Furthermore, the extent that PEP during treatment was associated with reduced treatment response to individual and group CBT for social anxiety disorder was evaluated. It was hypothesized that PEP would decrease following treatment as compared to a wait list control. Furthermore, PEP was expected to be associated with a reduced rate of change in social anxiety over the course of treatment.

Methods

The data for the current study came from a larger, NIMH funded randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of an experimental virtual reality exposure treatment (VRE; Anderson, Zimand, Hodges, & Rothbaum, 2005) for social anxiety with a primary fear of public speaking. VRE was compared to an exposure-based group treatment (EGT; Hofmann, 1999) and a waitlist control.

Participants

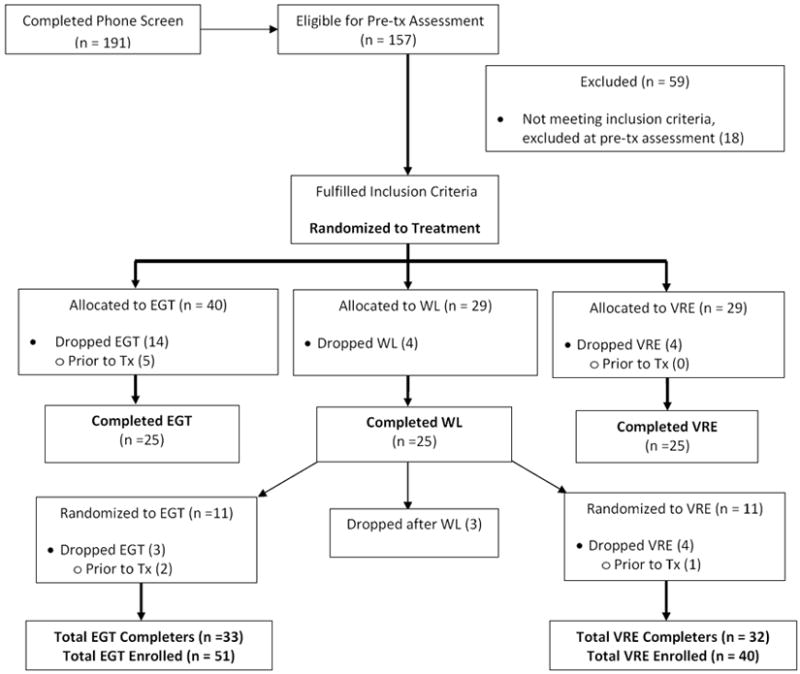

Participants were 91 individuals diagnosed with social anxiety. Half of the sample met criteria for the generalized subtype of social anxiety (n = 46). Most participants did not have a co-morbid diagnosis (n = 69, 76%). Participants were recruited broadly through newspaper advertising, posted flyers, and internet-based outlets seeking participants with fears of public speaking. Inclusion criteria included English speakers meeting DSM-IV (APA, 2000) criteria for a diagnosis of social anxiety who reported that their primary social fear was public speaking. Participants on psychoactive medication were required to be stabilized on their current medication(s) and dosage(s) for at least three months and were to remain at the same dosage throughout the course of the study. Individuals meeting any of the following criteria were excluded, (a) history of mania, schizophrenia, or other psychoses; (b) current suicidal ideation; (c) current alcohol or substance dependence; (d) inability to tolerate the virtual reality helmet; (e) history of seizures. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants over the course of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants through study.

The sample was predominately female (61%, n = 55) with an average age of M = 39.08, SD = 11.24. Participants self-identified as “Caucasian” (n = 43), “African American” (n = 33), “Hispanic” (n = 4), and “Asian American” (n = 2). The remaining (n = 9) participants reported their ethnicity as “Other.” The sample was well educated, with 64% completing college. With regard to other demographic information, 37% reported their relationship status as married and 42% reported an annual income of $50,000 or more.

Measures

Fear of Negative Evaluation - Brief Form (FNE-BF; Watson & Friend, 1969)

The FNE-BF is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that assesses cognitions about negative evaluation for a variety of situations. Responses are measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely) with overall scores ranging from 5 to 60. Sample items include thoughts about social fears such as “I am frequently afraid of other people noticing my short comings.” The FNE-BF has demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94 - 0.98) and 1-month test-retest reliability (r = 0.78 - 0.94).

Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker (PRCS; Paul, 1966)

The PRCS is a 30-item self-report questionnaire that assesses behavioral and cognitive responses to public speaking. Answers are recorded in a True False format with summary scores ranging from 0-30. Higher scores indicate less confidence with public speaking. Sample items include “While preparing a speech, I am in a constant state of anxiety.”

Rumination Questionnaire (RQ; Mellings & Alden, 2000)

The RQ is a 5-item self-report questionnaire that assesses PEP for a recent public speaking opportunity. This measure was chosen because both treatments in this study utilized public speaking situations for exposure. Questions assess the frequency that a person has thought about their most recent speech and the negativity of these thoughts. Sample items include “To what extent did you think about the anxiety you felt during your last speech?” Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much), with summary scores ranging from 5 to 35.

Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID: First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams,2002)

The SCID is a diagnostic interview that is used to assess psychological disorders based upon the criteria of the DSM-IV. For the current project, the SCID was used to establish clinical diagnoses for participants. A licensed clinical psychologist made independent ratings of the primary diagnosis for a randomly selected subset of the sample (n =15). Interrater reliability amongst these ratings was 100%.

Procedure

Eligibility for the current study was determined through a two-stage process. First, participants completed a telephone screen to identify exclusion criteria such as active suicidal ideation, active substance abuse, current enrollment in therapy for social anxiety, a history of mania, and having started or having changed dosage of a psychotropic medication within the past three months. Second, candidates were invited for an in-person assessment during which the SCID was used to determine if the participant met inclusion criteria for a primary diagnosis of social anxiety and other co-morbid disorders. Participants were randomly assigned using a simple randomization procedure. The randomization procedure was administered by the project coordinator, using a random number generator according to ID number. Assignment was made following the pretreatment assessment and enrollment to the study.

Assessments

Participants were given self-report measures prior to being randomized to a condition (pretreatment), at the end of the fourth session (midtreatment), and at the end of the eighth session (posttreatment). Waitlist participants completed self-report measures at pretreatment and after an eight-week waiting period. Following the waitlist period and assessment, waitlist participants were randomly assigned to one of the two active treatments using the same procedure described above.

Treatment

Both treatments consisted of eight sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, and targeted several processes shown to maintain social anxiety, including self-focused attention, negative perceptions of self and others, perceptions of lack of emotional control, and realistic goal setting for social situations. Although PEP was described as a maintaining factor for social anxiety disorder during each treatment, there was not a sustained focus on this process. The primary difference between the two therapies was the modality of exposure, delivered either in a group setting using other group members for exposure (EGT) or using virtual reality for exposure (VRE). Both treatments were administered according to a manualized protocol (Anderson, Zimand, Hodges, & Rothbaum, 2005; Hofmann, 2004). The virtual reality (VR) scenarios included 1) a conference room (~5 people), 2) a classroom (~35 people), and 3) a large auditorium (+100 people). These scenarios were presented via a head-mounted display (HMD) that consisted of a helmet with headphones and goggles. The therapist was able to communicate with the participant through a microphone to encourage sustained contact with the feared stimuli. Exposure was conducted according to individualized fear hierarchies within the parameters of the virtual environments. EGT was conducted in groups of 3-6 participants led by two therapists. Exposures primarily consisted of having participants give brief speeches in front of the group, with the group members providing feedback. Later sessions involved exposure with social mishaps. The final session for both treatments discussed relapse prevention and reviewed what was learned during the course of therapy.

Data analysis

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to assess all of the hypotheses for the current study1. To assess the extent that changes in PEP varied across EGT, VRE, and WL, a multilevel model was fitted to the data that included a fixed effect for VRE, EGT, and pretreatment PEP with the WL condition serving as the comparison group. A linear change model could not be fitted because of a lack of a midtreatment measurement point for the WL condition. Another multilevel model was used to assess the association between PEP and treatment response that included fixed effects for the pretreatment severity, time, PEP, and a PEP x time interaction. An additional level that contained a random effect for the EGT variable was added to all models to account for the partial nestedness of the data. Partial nesting refers to data in which a portion is organized into groups and a portion are treated as individuals (Bauer, Sterba, & Hallfors, 2008). The present study are organized in such a fashion because two of the arms of the study are individual-based (VRE, WL) and one arm is group-based (EGT). Because EGT is a group-based treatment, some of variance in treatment outcome may be accounted for by the shared experience of participating in a particular group.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all variables can be found in Table 1. A series of ANOVAs and chi-squares were conducted as a randomization check. For measures of social anxiety, there were no pretreatment differences across the three conditions, PRCS: F (2, 72) = 0.27, p = 0.77; FNE-BF: F (2, 72) = 1.42, p = 0.29. A test of independence revealed no significant differences in the demographic characteristics across the treatment conditions, Gender: χ2 (2) = 2.02, p = 0.33; Ethnicity: χ2(8) = 5.32, p = 0.72; Education: χ2(12) = 7.00, p = 0.86; Marital Status: χ2(10) = 5.67, p = 0.84; Income: χ2(10) = 10.58, p = 0.39.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the three treatment arms.

| Pretreatment | Midtreatment | Posttreatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNE-BF | VRE | 41.72 (10.65) | 42.34 (9.22) | 37.78 (9.31) |

| EGT | 43.97 (7.64) | 40.01 (9.40) | 35.13 (6.66) | |

| WL | 42.88 (9.68) | - | 42.36 (10.16) | |

| PRCS | VRE | 23.75 (2.37) | 22.87 (3.53) | 16.72 (6.44) |

| EGT | 24.61 (2.14) | 18.90 (5.02) | 11.50 (5.22) | |

| WL | 24.96 (2.89) | - | 23.57 (4.46) | |

| RQ | VRE | 23.56 (4.80) | 19.54 (7.11) | 14.48 (6.09) |

| EGT | 25.12 (6.70) | 16.75 (7.50) | 13.88 (5.40) | |

| WL | 26.92 (5.83) | - | 24.08 (6.45) |

Note: Values in parentheses are standard deviations. FNE-BF = Fear of Negative Evaluation. PRCS = Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker. RQ = Rumination Questionnaire for on the initial group assignment for participants. VRE = Virtual Reality Exposure. EGT = Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy. WL = Waitlist.

Comparison of PEP across the three treatment conditions

The findings from the model comparing changes in RQ scores across the treatment conditions model suggested that RQ scores significantly declined from pretreatment to posttreatment for VRE and EGT as compared to WL, VR: β10i = -8.82, p < 0.01; EGT: β20i = -9.85, p < 0.01 (Table 2). Treatment (vs. WL) had a large effect, accounting for 33% of the variance in posttreatment PEP scores. The level 2 model indicated that there were no differences among the groups in the EGT condition. A secondary analysis indicated that after controlling for pretreatment RQ scores, there was no difference between the VRE and EGT conditions on posttreatment RQ scores, β20i = 0.62, p = 0.62.

Table 2.

Comparison of EBT and VRE posttreatment RQ scores to WL Scores.

| Parameter | RQ | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept | β00i | 17.66** (3.88) |

| VRE | β10i | -8.83** (1.85) |

| EGT | β20i | -9.81** (1.63) |

| Pretreatment | β30i | 0.24 (0.13) |

| Random Effects | ||

| Level 1 | e2 | 32.52 |

| Level 2 | r2 2i | 0.06 |

Note:

= p < 0.05.

= p < 0.01.

RQ = Rumination Questionnaire. VRE = Virtual Reality Exposure. EGT = Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy.

Effect of PEP on changes in social anxiety

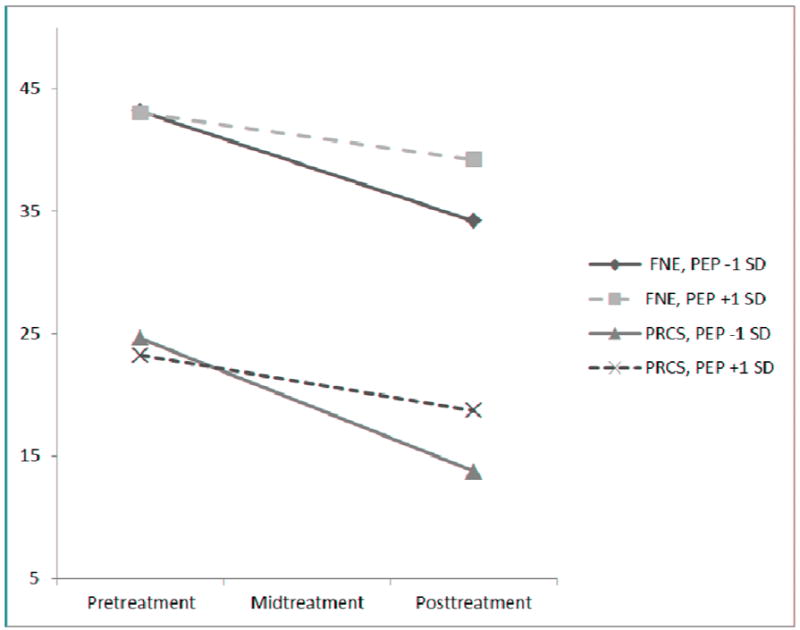

To address the extent that PEP impacted the rate of change in social anxiety during treatment, an intent to treat sample was used that included treatment completers, dropouts, and participants that completed treatment after WL, which yielded a total sample size of N = 91 (nVRE = 40, nEGT = 51)2. There was a main effect for time (PRCS: γ100 = -8.91, p < 0.01; FNE-BF: γ100 = -6.54, p < 0.01) and for RQ scores (PRCS: γ200 = 0.09, p < 0.05; FNE-BF: γ200 = 0.22, p < 0.05) (Table 3). Change over time accounted for 45% of the variance in PRCS scores and 60% of the variance in FNE scores. The effect of RQ scores was small, accounting for 5% of the variance in PRCS scores and 10% of the variance in FNE-BF scores. The interaction between RQ scores and time was significant for both the PRCS (γ300 = 0.33, p < 0.01) and the FNE-BF (γ300 = 0.30, p < 0.01), accounting for 12% and 6% of the variance respectively. This suggests that PEP had a small to medium effect on changes in social anxiety symptoms during treatment (Figure 2) such that higher levels of PEP over time were associated with poorer treatment response. Furthermore, this association did not differ across the VRE and EGT groups for both outcome measures. Finally, the level 3 random effects were not significant for both dependent variables, indicating that there were no significant differences amongst the groups in the EGT condition.

Table 3.

Piecewise model examining the impact of RQ on the rate of change in the PRCS and FNE-BF

| Parameter | PRCS | FNE-BF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | |||

| Pretreatment | γ000 | 21.86**(1.02) | 34.27**(2.99) |

| Treatment rate of change | γ100 | -8.91** (1.09) | -6.06** (1.49) |

| Difference between VRE & EBGT for treatment | γ110 | <0.01 (0.01) | -0.35 (1.79) |

| PEP | γ200 | 0.09* (0.04) | 0.22* (0.13) |

| Difference between VRE & EBGT for PEP | γ210 | <0.01 (0.02) | < 0.01 (0.08) |

| Interaction between PEP and Treatment Period | γ300 | 0.33** (0.05) | 0.30** (0.09) |

| Difference between VRE & EGT | γ310 | -0.16 (0.07) | -0.35 (0.28) |

| Random Effects | |||

| Level 1 | e2 | 7.68 | 29.06 |

| Level 2 | r2 0 | 0.33 | 37.83 |

| r2 1 | 5.87* | 0.16 | |

| r2 2 | <0.01 | 0.09 | |

| Level 3 | u12 | 2.75 | 12.29 |

| u22 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| u32 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

Note:

= p < 0.05.

= p < 0.01.

Values in parentheses are standard errors. FNE-BF = Fear of Negative Evaluation. PRCS = Personal Report of Confidence as a Speaker. VRE = Virtual Reality Exposure. EGT = Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy.

Figure 2.

Rate of change for PRCS and FNE-BF for +1 and -1 standard deviation of RQ.

Discussion

The results of this study show that PEP declined following treatment, which is consistent with prior research (Abbott & Rapee, 2004; McEvoy et al., 2009). However, this is the first study to examine whether PEP declines as a result of treatment using a controlled design. Interestingly, none of the treatments across these studies contained interventions that focused explicitly on PEP and so future work should attempt to discern what components of the current treatment packages contributed to the reductions in this process. Additionally, research should attempt to develop interventions that would explicitly target PEP. Results also showed that PEP was associated with a reduced rate of change in social anxiety symptoms over the course of treatment for both VRE and EGT.

This study is the first to show that PEP attenuates response to treatment for social anxiety disorder. However, the mechanism by which this occurs is unknown. Prior research offers two potential explanations. Telch and colleagues (2004) argued that distraction reduces treatment response by increasing the client’s cognitive load during treatment, which, in turn, inhibits the consolidation of non-fearful learning. From this perspective, PEP may increase cognitive load between sessions, which limits the resources available for consolidating extinction learning. Alternatively, other theorists have argued that treatment response is determined by the strength of non-fearful associations that are formed during treatment (Craske et al., 2008). The strength of such associations is determined by context and the frequency of contact with the feared stimulus. Novel contexts and decreased contact with the feared stimulus are believed to strengthen the activation of the non-fearful association. From this perspective, PEP may increase the chance that the fear pathway is activated between sessions. This increased activation would allow the fear response to generalize to more contexts and lead to more frequent encounters with the stimulus. Thus, the strength of the non-fearful associations that are acquired during treatment would be weakened, which would limit overall treatment response. Further research on the mechanisms of change for CBT are needed to better understand how PEP interferes with treatment outcome, whether it be increasing cognitive load, reducing the strength of non-fearful pathways, or another mechanism.

There are important limitations to the current study, particularly with regard to the manner in which PEP was assessed. The current study examined PEP for the previous week at the end of an exposure therapy session, which renders it vulnerable to recall bias. It may be more beneficial to assess PEP at the start of a treatment session to avoid any interference from the exposures of the current session. Alternatively, a more accurate method of assessing PEP would involve methods to assess participant’s “online” thoughts throughout the course of the week. This could involve journaling in which participants note their thoughts about their past speech. Another method that may be useful would be sending participants cues throughout the day electronically (e.g. text messages, e-mails) asking them to note the frequency of their PEP (Boschen, 2009). Additionally, there are alternative measures (that were not yet developed at the time the present study began) that may better assess the construct of PEP, including the PEP Questionnaire (PEP-Q; Fehm, Hoyer, Schneider, Lindemann, & Klusmann, 2008; McEvoy & Kingsep, 2006) and the Repetitive Negative Thinking Questionnaire (RNT; McEvoy, Mahoney, & Moulds, 2010).

Another limitation is that the current study examined PEP within a sample of individuals diagnosed with social phobia whose primary fear was public speaking and underwent exposures that focused exclusively on public speaking. We did not collect qualitative data about the content of PEP, and although we can be sure that each participant encountered a public speaking situation from week to week (because exposure therapy consisted of public speaking tasks), we do not know whether participants reported PEP for the speech during exposure therapy or some other social situation encountered between sessions. This is important because a recent review (Blöte, Kint, Miers, & Westenberg, 2009) questioned the utility of speech tasks for assessing social anxiety symptoms, and suggested that public speaking anxiety may be a specific subtype of social phobia. Future research is needed to assess the extent that these findings generalize to individuals with social phobia who do not report public speaking as their primary social fear.

Also, the rate of co-morbidity in the current sample (12%) deserves mention, as it is lower than what is typically found for individuals with social anxiety disorder. The relative lack of co-morbidity may be related to the fact that we advertised the present study as one targeting public speaking fears, as well as a study that included a technology-based treatment (VRE). Indeed, the rate of co-morbidity in the current study is comparable to recent studies utilizing internet-based or virtual reality exposure therapy for public speaking fears (7% - 12.5%; Andersson et al., 2006; Botella et al., 2008). Despite lower levels of co-morbidity, participants’ self-report of social anxiety symptoms were elevated as compared to non-clinical samples (Duke, Krishnan, Faith, & Storch, 2006). Although this sample may be less impaired with regard to psychiatric co-morbidity than other treatment-seeking samples, participants appeared to be impacted by their public speaking and other social fears, as evidenced by meeting DSM-IV criteria for social anxiety disorder and by self-reported levels on standardized measures of social anxiety symptoms.

Overall, the present study is the first to show that PEP decreases after a course of CBT using a controlled design. It also is the first study to examine whether PEP is negatively related to the rate of change in social anxiety symptoms during the course of treatment. Future work should attempt to understand how PEP is associated with a poorer response to therapy, which may in turn lead to improved interventions for PEP itself or to an understanding of how to reduce its impact on the treatment process.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this paper was supported in part by grants to the first author from the American Psychological Association and Georgia State University and the NIMH R42 MH 60506-02 grant awarded to the second author. This project was completed by the first author as part of their dissertation work.

Footnotes

Full models for the current study are available upon request from the first author.

The analyses were run with the sample of treatment completers and the exact same findings were obtained.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott MJ, Rapee RM. Post-Event Rumination and Negative Self-Appraisal in Social Phobia Before and After Treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):136–144. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PL, Zimand E, Hodges LF, Rothbaum BO. Cognitive behavioral therapy for public-speaking anxiety using virtual reality for exposure. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(3):156–158. doi: 10.1002/da.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Carlbring P, Holmström A, Sparthan E, Furmark T, Nilsson-Ihrfelt E, et al. Internet-based self-help with therapist feedback and in vivo group exposure for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(4):677–686. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR Fourth Edition (Text Revision) American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Sterba SK, Hallfors DD. Evaluting Group-Based Interventions When Control Participants Are Ungrouped. Multivariate Behavioral Reesearch. 2008;43:210–236. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöte AW, Kint MJW, Miers AC, Westenberg PM. The relation between public speaking anxiety and social anxiety: A review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(3):305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschen MJ. Mobile telephones and psychotherpay: II A review of empirical research. The Behavior Therapist. 2009;32(8):175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Botella C, Gallego MJ, Garcia-Palacios A, Baños RM, Quero S, Guillen V. An Internet-based self-help program for the treatment of fear of public speaking: A case study. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2008;26(2-4):182–202. [Google Scholar]

- Brozovich F, Heimberg RG. An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(6):891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. The role of memory perspective in social phobia: Immediate and delayed memories for role-played situations. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;30(4):415–425. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(1):5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple KL, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification. 2007;31(5):543–568. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannahy L, Stopa L. Post-event processing in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(6):1207–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke D, Krishnan M, Faith M, Storch EA. The psychometric properties of the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(6):807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Franklin J. Postevent Rumination and Recall Bias for a Social Performance Event in High and Low Socially Anxious Individuals. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2003;27(6):603. [Google Scholar]

- Fehm L, Hoyer Jr, Schneider G, Lindemann C, Klusmann U. Assessing post-event processing after social situations: A measure based on the cognitive model for social phobia. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2008;21(2):129–142. doi: 10.1080/10615800701424672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP, Psychol C, Morgan J. Post-event processing and the retrieval of autobiographical memories in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18(5):647–663. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV-TR axis 1 disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, et al. Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1133–1141. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JD, Gaudiano BA, Rheingold AA, Myers VH, Dalrymple K, Nolan EM. Social Skills Training Augments the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(2):125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Behavior group therapy for social phobia. Boston University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive Mediation of Treatment Change in Social Phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):392–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocovski NL, Rector NA. Post-event processing in social anxiety disorder: Idiosyncratic priming in the course of CBT. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Kingsep P. The post-event processing questionnaire in a clinical sample with social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(11):1689–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Mahoney A, Perini SJ, Kingsep P. Changes in post-event processing and metacognitions during cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(5):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Mahoney AEJ, Moulds ML. Are worry, rumination, and post-event processing one and the same?: Development of the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(5):509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellings TMB, Alden LE. Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38(3):243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul GL. Insight vs desensitization in psychotherapy. Standford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Perini SJ, Abbott MJ, Rapee RM. Perception of Performance as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Social Anxiety and Negative Post-Event Rumination. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(5):645–659. [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S, Grater-Andrew J, Shafran R. Post-event processing in social anxiety. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38(6):611–617. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(8):741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe MK, Craske MG. Effects of an expanding-spaced vs massed exposure schedule on fear reduction and return of fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(7):701–717. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch MJ, Valentiner DP, Ilai D, Young PR, Powers MB, Smits JAJ. Fear activation and distraction during the emotional processing of claustrophobic fear. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2004;35(3):219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao JCI, Craske MG. Timing of treatment and return of fear: Effects of massed, uniform-, and expanding-spaced exposure schedules. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31(3):479–497. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]