Abstract

Genetic and physical maps for the 16 chromosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are presented. The genetic map is the result of 40 years of genetic analysis. The physical map was produced from the results of an international systematic sequencing effort. The data for the maps are accessible electronically from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD: http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/).

During the past 40 years, 11 compilations of mapping data for the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been made by R. K. Mortimer and colleagues1–11. The last such compilation11 included mapping data to 1991, and contained for the first time the results of physical as well as genetic mapping methods. Here we present the twelfth, and probably the last, such compilation. These final maps are based on the genetic information accumulated over the years1–11 and, for the physical mapping data, on an entirely new set of data: the complete genomic sequence of S. cerevisiae.

The genetic and physical maps were derived from two entirely different types of data. Genetic distances between genes were determined by tetrad analysis. Distances for gene–gene and gene–centromere linkages are expressed in centimorgans (cM) and were calculated using a maximum-likelihood equation12 which yields values for map distance, an interference parameter, and error calculations for these two parameters. Mapping results on more than 2,600 named genes are presented. Physical distances are calculated directly from the complete DNA sequence. The precise values of all parameters (both tetrad analysis results and chromosomal base-pair coordinates) are available from the SGD.

Associations between open reading frames (ORFs) and corresponding mutations were made using a set of hybridization filters, originally produced by L. Riles and M. Olson13, which are now available from the American Type Culture Collection (http://www.atcc.org/). Other such associations were made by complementation experiments using cloned DNA fragments and/or sequence analysis of mutants. The data for some of these associations are published, but the documentation for all of them can be found on SGD.

Now that the entire yeast genome sequence is available, most revisions of the map will consist of associations between a biological function and an ORF. These associations will often involve the study of mutants of the gene. In the past, such an association invariably resulted in the naming of the gene; this process is likely to continue until all of the genes have been associated with a function and have thereby acquired a name. Because the genetic and physical maps are unlikely to change significantly, we see no need for any future publications; rather, we expect the electronic version of the maps to evolve into increasingly accurate guides to S. cerevisiae biology.

The maps shown here are also available in a continually updated electronic form from the SGD (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/), which will also provide directions to other useful information (gene names, aliases, phenotypes, mapping data, protein information, and curated compilations of published literature about genes).

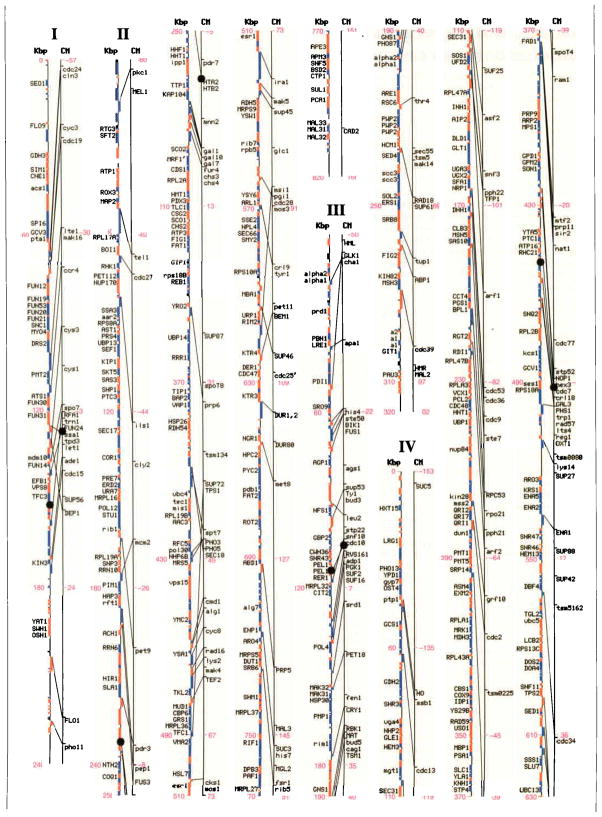

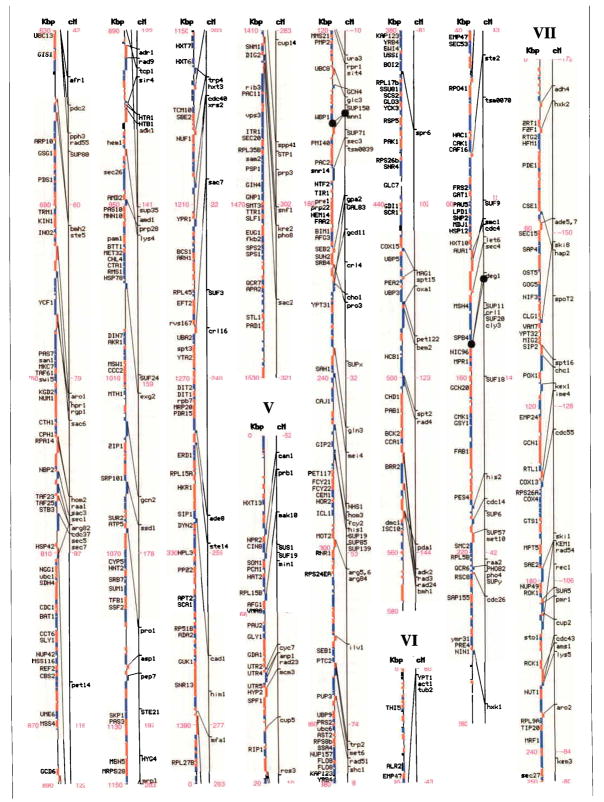

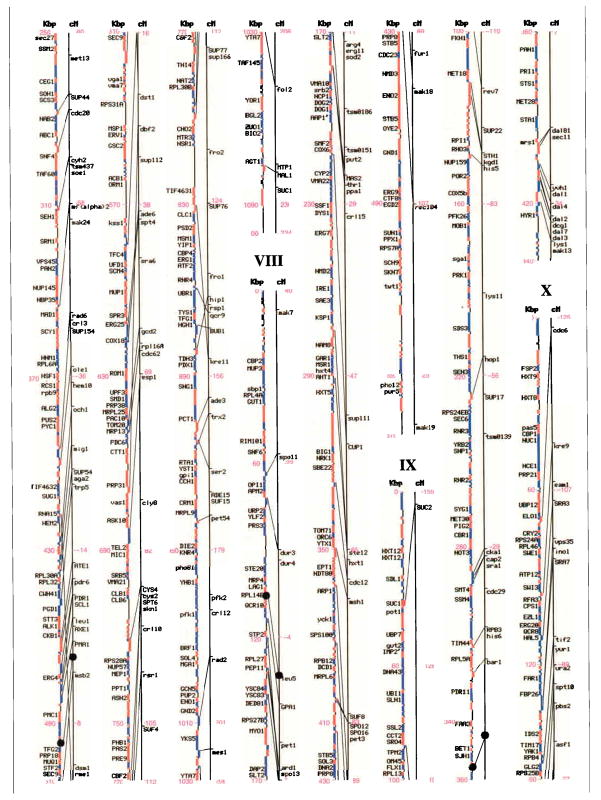

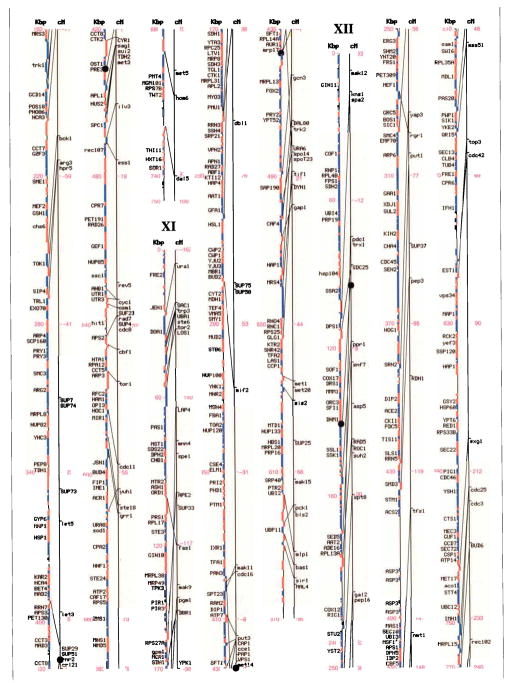

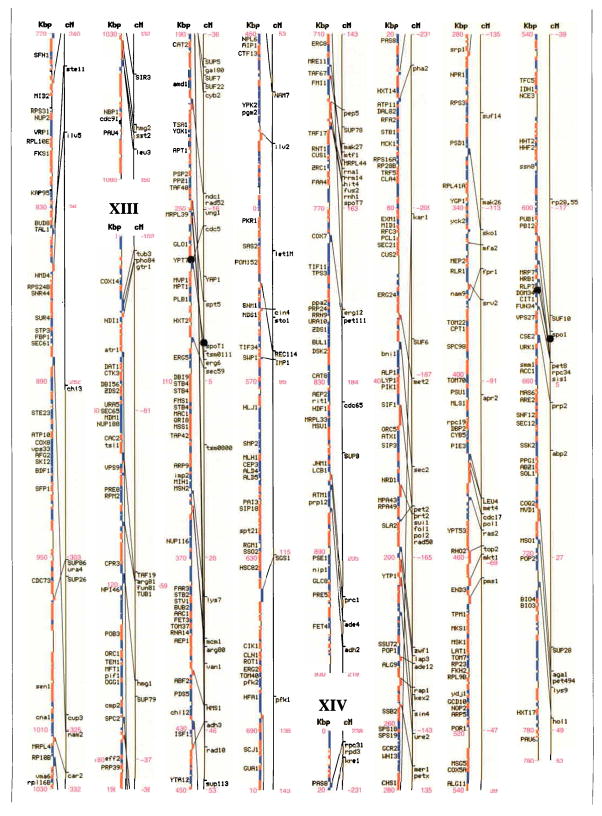

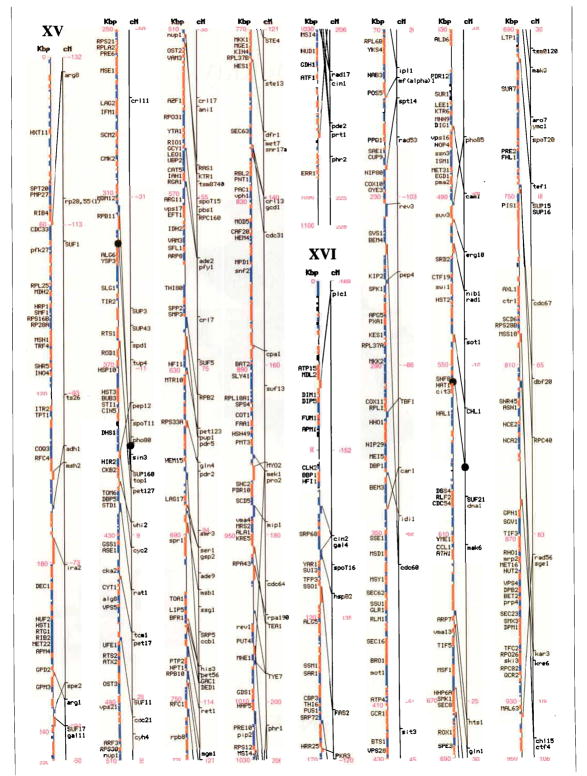

Figures I–XVI.

Genetic and physical maps, and their correlations, of the 16 Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes. A parallel comparison of the physical map (left, in kilobase pairs) and the genetic map (right, in centimorgans) of each of the 16 chromosomes is illustrated. The information in this figure is available on the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/Saccharomyces/). The physical map consists of coloured boxes that indicate ORFs. ORFs on the Watson strand (left telomere is the 5′ end of this strand) are shown as red boxes, those on the Crick strand as blue boxes. Where it has been defined, the gene name of an ORF is indicated. The genetic map is based on data collected since 1991 by the SGD project, as well as on earlier data1–11. Horizontal tick marks on the right of the genetic map line indicate positions of genes. Lines connect genetically mapped genes with their ORF on the physical map. A single name is listed for known synonyms.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the yeast researchers, who are too numerous to name individually; F. Dietrich, M. Johnston, E. W. Jones, M. Olson and B. F. F. Ouellette for criticism; A. Goffeau, for encouragement and advice and J. Garrels, D. Lipman, A. Bairoch and H. W. Mewes for their continuing collaboration. S. G. D. is funded by a grant from the National Center for Human Genome Research.

References

- 1.Hawthorne DC, Mortimer RK. Genetics. 1960;45:1085–1110. doi: 10.1093/genetics/45.8.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortimer RK, Hawthorne DC. Genetics. 1966;53:165–173. doi: 10.1093/genetics/53.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawthorne DC, Mortimer RK. Genetics. 1968;60:735–742. doi: 10.1093/genetics/60.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortimer RK, Hawthorne DC. Genetics. 1973;74:33–54. doi: 10.1093/genetics/74.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortimer RK, Hawthorne DC. Methods Cell Biol. 1975;11:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortimer RK, Schild D. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:519–571. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.4.519-571.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortimer RK, Schild D. The Molecular Biology of the Yeast. In: Strathern JN, Jones EW, Broach JR, editors. Saccharomyces: Metabolism and Gene Expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; NY: 1982. pp. 639–650. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortimer RK, Schild D. Microbiol Sci. 1984;1:145–146. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortimer RK, Schild D. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:181–213. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.3.181-213.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mortimer RK, Schild D, Contopoulou CR, Kans J. Yeast. 1989;5:321–404. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortimer RK, Contopoulou CR, King JS. Yeast. 1992;8:817–902. doi: 10.1002/yea.320081002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King JS, Mortimer RK. Genetics. 1991;129:597–601. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riles L, et al. Genetics. 1993;134:81–150. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]