Abstract

Endothelial protein kinase C (PKC) signaling was investigated in different regions of normal porcine aorta. The locations map to differential atherosclerotic susceptibility and correlate with sites of disturbed (DF) or undisturbed (UF) local flow profiles. Endothelial lysates were isolated from the inner curvature of the aortic arch (DF; athero-susceptible) and a nearby UF region of the descending thoracic aorta (UF; athero-protected), and in some experiments a distant athero-protected UF site, the common carotid artery. Total endothelial PKC activity in the DF regions was 145% to 240% of that in both UF locations (P<0.05), whereas the UF regions were not significantly different from each other. PKC protein isoforms α, β, ε, ι, λ, and ζ were expressed in similar proportions in both aortic regions, suggesting that differences of kinase activity were not directly attributable to expression levels. Inhibition of members of the “conventional” and “novel” PKC families had no differential effect on regional kinase activity. However, inhibition of PKCζ, a member of the “atypical” PKC family, reduced the DF lysate kinase activity to that of UF levels (NS P=0.35). Differential phosphorylation of PKCζ Thr410 and Thr560, along with increased levels of PKCζ degradation products in UF endothelial lysates, suggested posttranslational modification of PKCζ as the basis for site-specific differences in vivo. Steady-state regional heterogeneity of an important family of regulatory proteins in intact arterial endothelium in vivo may link localized athero-susceptibility and the associated hemodynamic environment.

Keywords: endothelial phenotypic heterogeneity, site-specific PKC activity, flow disturbance, hemodynamics

In regions of the arterial vasculature that exhibit complex hemodynamics associated with laminar flow separations and transient turbulence (collectively “disturbed flow”, DF), there is a predilection for the development of atherosclerotic lesions.1 The regulation of endothelial biology by hemodynamic forces, particularly shear stress, is well established,2 as is the link between endothelial functional changes, and by implication phenotype, to the focal initiation and development of lesions.3 We have proposed that endothelial phenotypic heterogeneity within arteries over relatively short length scales accounts for localized athero-susceptibility while adjacent regions are protected.4

The diversity of endothelial phenotype from different vascular beds persists in tissue culture as demonstrated by transcript profiles of cultured endothelial cells isolated from distinct anatomic locations.5 Functional heterogeneity, demonstrated by variations in lymphocyte recruitment, has also been shown in endothelial cells cultured from different organs.6 Investigations over a narrower spatial scale and conducted on endothelium directly isolated from fresh arteries has recently revealed differential transcriptional regulation of athero-protective and athero-susceptible pathways in discrete aortic locations.7 A similar spatial approach to the aortic valve endothelium has revealed side-specific transcript expression.8 Together these studies demonstrate that endothelial cells in vivo display a range of phenotypes. Regional susceptibility to, or protection from, pathological change is likely related to such endothelial heterogeneity.

The biology of endothelium residing at locations that predictably develop atherosclerotic plaques can be investigated by studying the phenotype differences between athero-susceptible and athero-protected vascular regions in situ or after isolation from circumscribed locations. The spatial distribution of phenotype diversity in vivo has been demonstrated at the transcript level by microarray analysis7 but few studies have addressed protein expression, posttranslational modifications, and cell function in relation to hemodynamics and focal/regional vulnerability to atherosclerosis.

PKC is a prominent example of a regulatory signaling pathway that links extracellular events to intracellular responses, and which has been directly implicated in atherogenesis. Among its many roles, PKC activity is necessary for leukocyte recruitment9 and free radical production by endothelial cells in diabetic atherosclerosis,10 and mediates ICAM-1 upregulation.11 PKC is a family of serine/threonine kinases which have been divided into 3 classes of isozymes based on their domain structure and activity profiles. The “conventional” family of PKCs (α, β, γ) is Ca2+-dependent, diacylglycerol (DAG) sensitive, and can be activated by phorbol esters. The “novel” family (δ, ε, η, θ) is Ca2+-independent, DAG sensitive, and activated by phorbol esters. The “atypical” family (ζ, ι, λ) is Ca2+-independent and DAG and phorbol ester-insensitive. PKC isozymes have also been shown to require phosphorylation for full activity.12 The intracellular localization of each isozyme is mediated by specific anchoring proteins,13 having a profound impact on the substrate specificity of individual PKC isozymes. At least 2 isozymes (β and ε) were previously found to be shear-sensitive in vascular endothelial cells in culture.14,15

Here we investigate regional heterogeneity of endothelial PKC expression and activation at arterial locations distinguished both by different hemodynamic characteristics and athero-susceptibility, and report site-specific differences in PKCζ activity and posttranslational modifications.

Materials and Methods

Expanded materials and methods are available in the online supplement at http://circres.ahajournals.org.

Sample Isolation

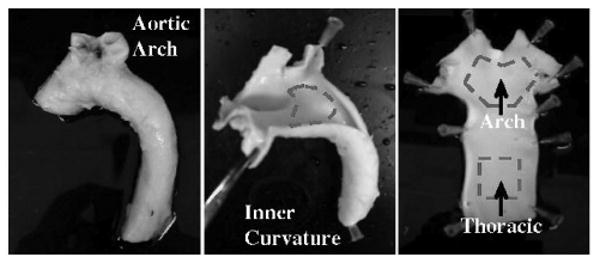

The ascending aorta, aortic arch, descending thoracic aorta, and common carotid arteries were dissected from adult male pigs obtained immediately after euthanization (Hatfield Industries, Hatfield, Pa). The tissues were flushed with sterile ice-cold PBS and incised lengthwise (Figure 1). Endothelial cells were gently scraped from 2 cm2 regions located (i) at a region of flow separation and disturbance (DF), the inner curvature of the aortic arch, (ii) a nearby region of undisturbed unidirectional flow (UF) in the descending thoracic aorta, and (iii) the mid-section of the common carotid artery, a second UF site. The presence of flow reversal in the aortic arch of adult boars, similar to that measured in humans has been previously confirmed.7 The cells were transferred directly into 100 μL of lysis buffer (TBS, 1% Triton X-100, protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for transport to the laboratory. The lysates were thawed, agitated for 10 minutes at 4°C, centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. We have previously characterized the purity of endothelial cell isolates by immunocytochemistry;7 as a further check, immunoblotting for the smooth muscle cell marker calponin was performed on each sample (online Figure I). Any sample that showed detectable calponin was discarded.

Figure 1.

Isolation of porcine aortic endothelium. Left and center, Porcine aortas from adult male pigs were dissected from the surrounding tissue, flushed with cold sterile PBS, and incised lengthwise. Right, Endothelial cells were gently scraped from the inner curvature of the aortic arch (DF) and from the descending thoracic aorta (UF). The collected endothelial cells were immediately placed into lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and frozen in LN2. A similar method of isolation was used to collect endothelial lysates from the middle section of common carotid artery (UF).

Immunohistochemistry

The aorta was collected as in sample isolation, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Small sections (25 mm2) were cut from the aortic arch (DF) and the thoracic aorta (UF). The same anti-PKCζ antibody was used along with an Alexa-647 conjugated secondary antibody. Cell nuclei were counterstained with SYTOX Green and imaging was performed on a BioRad Radiance 2000 confocal microscope.

Immunoprecipitation

Lysates (50 μg) were incubated on a shaking platform with protein A coated agarose beads (Oncogene) for 1 hour in lysis buffer to preclear nonspecifically-binding proteins. The primary antibody was added to the cleared lysate and incubated overnight at 4°C. Protein A beads were added and the incubation was continued for an additional 2 hours. The beads were then collected by centrifugation and washed 5 times in cold lysis buffer. Protein was eluted with a low pH buffer (Immunopure IgG Elution Buffer, Pierce Biotechnology) at room temperature.

Immunoblotting

Five μg of protein was electrophoresed in a 4% to 12% polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) under denaturing and reducing conditions and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated for 1 hour with primary antibody. After 3 washes in PBS-T the membrane was incubated for 1 hour with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was performed by chemiluminescence (Western Lightning Reagents, Perkin Elmer Inc). Following development, the films were digitally scanned and stored as high-resolution TIFF images. The program ImageJ (NIH) was used for densitometric quantification of blots. In the preparation of each gel for quantification all samples were loaded onto a single gel and statistical tests were performed only within that gel.

PKC Activity Assay

PKC activity was measured by the transfer of 32P-phosphate to a synthetic peptide substrate (EMD Biosciences). 5 μL of protein lysate was incubated with γ32P-ATP and a biotinylated substrate for 5 minutes at 37°C. Reactions were terminated with the addition of 8 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride and collected on avidin-coated spin columns. Radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation. As a positive control, 5 ng of recombinant PKC (EMD Biosciences) was used. Two negative controls were run, one in which no substrate was added and another in which no kinase was added. All samples were run in triplicate. For each sample the specific activity was calculated as the amount of phosphate transferred per minute per milligram of total protein (pmol PO4/min/mg). For inhibition experiments, PKC inhibitors were added to the reaction mixture before the addition of γ32P-ATP.

Data Analysis

For each comparison, data from 4 animals were used. All quantitative data (protein concentrations, immunoblot densitometry, and PKC activity) were entered into Microsoft Excel for analysis and statistical testing. The comparison of means between groups was performed using Student t test. Results were considered statistically significant at probability values <0.05.

Results

Site-Specific PKC Activity in Porcine Arterial Endothelium

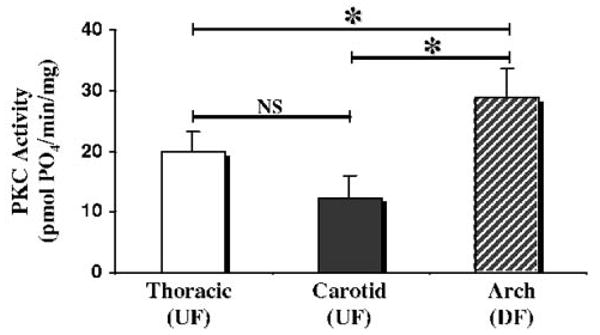

PKC activity in the endothelium of adult male pigs was measured using an in vitro kinase assay (Figure 2). To maintain consistent with our previous work,7 the inner curvature of the aortic arch and the proximal thoracic aorta were studied. Important distinctions between the sites are the presence of characteristic DF and UF hemodynamics in vivo and differential susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Kinase activity was also measured in endothelial lysates from the middle section of the common carotid artery, a more distant region of UF hemodynamics. Endothelial cell lysates from the DF region had 45% higher PKC activity (all isoforms) than matched samples from the thoracic region (29±5 versus 20±3 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05) and 140% higher activity than in the common carotid (29±5 versus 12±4 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05). Carotid artery endothelial lysates (UF) had activities similar to those isolated from the aortic UF site (12±4 versus 20±3 pmol PO4/min/mg, p=NS). These data suggested that hemodynamics, either directly or indirectly, regulate endothelial PKC activity. The levels of PKC activity are in the range reported for nonactivated cells,16 consistent with normal (nonatherosclerotic) healthy animals. In contrast, PKC activity levels in pathological settings have been reported 1 to 2 orders of magnitude higher.17

Figure 2.

Measurement of endothelial PKC activity in 3 regions. The activity level of PKC in endothelial lysates was measured using an in vitro kinase assay. Lysates from the aortic arch (DF) had 45% greater PKC activity than paired samples from the thoracic aorta (UF, 29±5 vs 20±3 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05) and 140% higher activity than in the common carotid (UF, 29±5 vs 12±4 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05). Thoracic aorta endothelial PKC activity was not significantly different from that of the carotid artery (20±3 vs 12±4 pmol PO4/min/mg, p=NS), a region with a similar UF hemodynamic profile. All measurements are the average of 4 independent samples. *P<0.05.

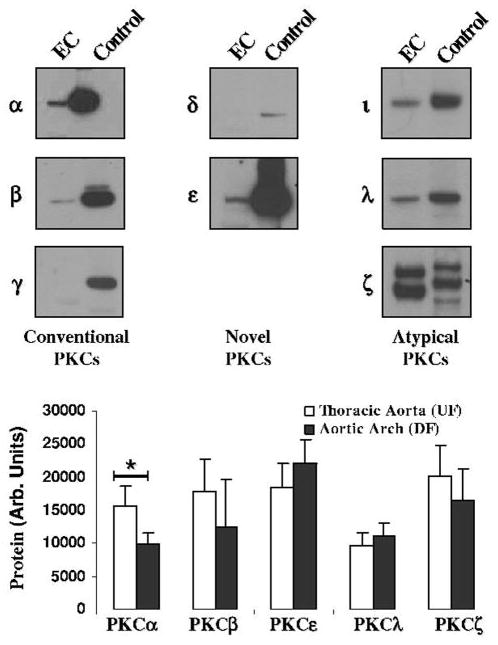

Expression Levels of PKC Isozymes Are Unrelated to Site-Specific Differential Activity

Previous reports have identified several PKC isozymes in cultured aortic endothelial cells;18 however, limited data are available concerning endothelial isoforms in vivo. A series of immunoblots (online Figure II) to identify the isoforms and their expression levels after removing endothelium directly from the artery revealed the presence of PKC isozymes alpha (α), beta (β), epsilon (ε), iota (ι), lambda (λ), and zeta (ζ) (Figure 3). All PKC isoforms were expressed in both DF and UF regions. To semiquantitatively measure the amount of each isozyme, 4 paired samples were run together on an immunoblot and measured by densitometry (Figure 3). Except for PKCα, no statistically significant differences were observed. Endothelial cell lysates from the UF aortic region contained 1.6-fold more PKCα than matched DF lysates (P<0.05), a result inconsistent (on the basis of PKC mass) with the lower PKC activity measured in the UF aortic region. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the active PKCα could translocate to a Triton-insoluble location, and thus not be detected in our lysates. These data demonstrate that the site-specific differential PKC activity could not be explained by transcriptional or translational regulation of isozyme expression, because expression of all isozymes except PKCα was unchanged between the 2 regions, and PKCα levels did not justify the higher activity levels measured in the aortic arch (DF).

Figure 3.

Identification and quantification of expressed PKC isozymes. Top, Using isozyme specific antibodies, a series of immunoblots was performed to identify those isozymes that were expressed by porcine aortic endothelial cells. For each isozyme the endothelial lysate (EC) and a positive control lysate (rat cerebral lysate, Control) were probed. Bottom, Densitometric quantification (n=4) of PKC isozyme expression showed that only PKCα was differentially regulated in the 2 regions. *P<0.05.

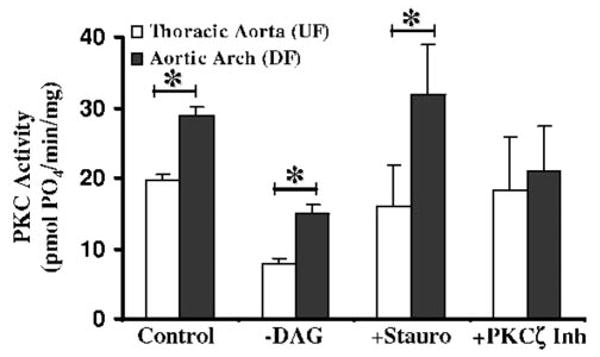

Differential Activation of PKCζ in the Aortic Arch

To determine the contributions of different PKC isozymes to the overall PKC activity, a series of in vitro kinase assays were run in which the reaction conditions were manipulated to inhibit specific PKC isozyme families (Figure 4). In the first set of experiments, the activator solution (3 mg/mL phosphatidylserine, 300 μg/mL diacylglycerol (DAG), and 3% Triton X-100) was withheld from the reaction mixture (–DAG). Although the absence of phosphatidylserine lowered the overall activity of all PKC isozymes, the site-specific differences in activity were retained (15±1 versus 7.9±0.6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05). Because only the conventional and novel PKC families are DAG sensitive, the data suggested that the atypical PKC family was differentially regulated between the 2 sites. To confirm this, staurosporine (10 nM) was added to the reaction mixture (+Stauro). At low concentrations staurosporine is reported to preferentially inhibit the conventional and novel isoforms of PKC.19 This selectivity was verified in our assay by testing staurosporine on recombinant PKC isozymes. Recombinant PKCη was inhibited by 70% (440±2 versus 150±9 pmol PO4/min/μg, P<0.01) while PKCζ was unaffected (79±5 versus 80±2 pmol PO4/min/μg) at 10 nM. At this concentration of staurosporine the PKC activity in aortic arch endothelial lysates (DF) remained significantly higher than the activity in the UF aorta lysates (32±7 versus 16±6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05), consistent with the experimental data in which DAG was withheld. Both interventions strongly suggested that the atypical class of PKC was responsible for the difference between the UF and DF regions. To distinguish between the individual atypical PKC isozymes, the in vitro kinase assay was repeated using a PKCζ pseudosubstrate peptide (40 μmol/L) that inhibits kinase activity by competing for the substrate-binding site on the enzyme (+PKCζ Inh). Again, to verify the selectivity of this inhibitor it was tested on recombinant PKCη, which was not significantly inhibited (150±8 versus 120±14 pmol PO4/min/μg, p=NS) by the zeta pseudopeptide. Addition of the pseudosubstrate PKCζ inhibitor eliminated the difference in activity between the 2 regions (18±6 versus 21±6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P=0.35). These 3 lines of evidence suggest that there were increased levels of PKCζ activity in the athero-susceptible aortic arch (DF).

Figure 4.

Local regulation of isozyme-specific activity. In one set of experiments (–DAG), the activator solution (a suspension of phosphatidylserine, diacylglycerol, and Triton) was withheld from the reaction mixture. Absence of phosphatidylserine lowers the overall activity of all PKC isozymes, but the difference between the 2 regions was maintained (15±1 vs 7.9±0.6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05). The differential PKC activity in the arch lysates (DF) compared with the thoracic aorta (UF) was retained despite inhibition of the conventional and novel classes by staurosporine (10 nM) (+Stauro, 32±7 vs 16±6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P<0.05). In contrast, addition of a pseudosubstrate PKCζ inhibitor (+PKCζ Inh) eliminated the difference in activity between the 2 regions (18±6 vs 21±6 pmol PO4/min/mg, P=0.35). All measurements are the average of 4 independent samples. *P<0.05.

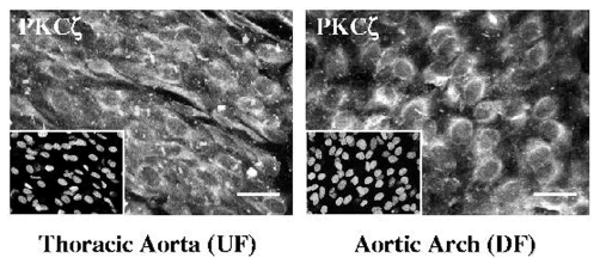

Many studies have demonstrated intracellular translocation of PKC isozymes on activation. To observe the distribution of endothelial PKCζ in the aortic arch (DF) and in the thoracic aorta (UF), en face confocal immunohistochemistry was performed. In both regions the endothelial PKCζ was primarily perinuclear (Figure 5). There were no obvious changes in either PKCζ abundance or localization, consistent with our immunoblots. In both the PKCζ staining and the nuclear counterstain (insets) the thoracic endothelial cells are elongated whereas the arch cells are more rounded, representative of the hemodynamic differences between these regions.

Figure 5.

Intracellular distribution of PKCζ. En face confocal immunohistochemistry was used to visualize PKCζ in the thoracic aorta (UF) and aortic arch (DF). In both regions the endothelial PKCζ was predominantly perinuclear. There were no obvious changes in either PKCζ abundance or localization. In both the PKCζ staining and the nuclear counterstain (insets) the thoracic endothelial cells exhibit characteristic elongated alignment with flow whereas the arch cells are more cobblestone-shaped. Scale bar is 20 μm.

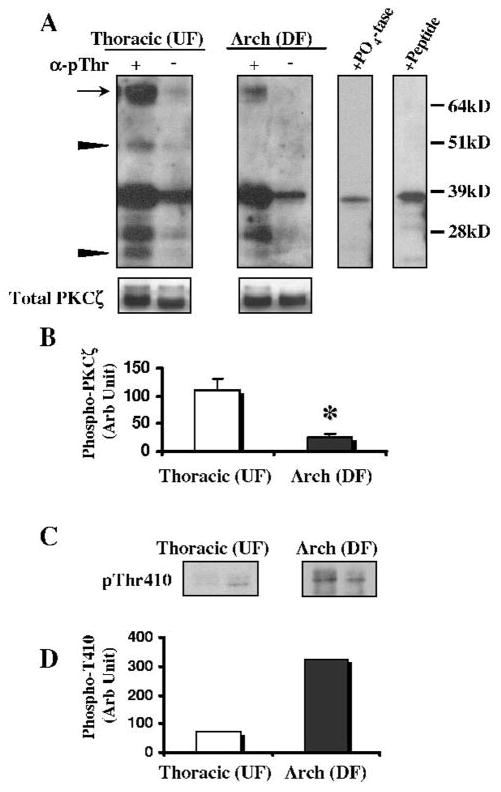

Site-Specific PKCζ Phosphorylation Differences

Endothelial protein lysates (50 μg) from the aortic arch (DF) and the thoracic aorta (UF) were immunoprecipitated using an antiphosphothreonine antibody, followed by PKCζ immunoblotting. The amount of PKCζ in the lysates before immunoprecipitation (Total PKCζ) was equal for all samples. As shown in Figure 6A, there was substantially more phosphorylated PKCζ (→) in the UF region than in the DF aortic arch, in apparent contradiction to increased PKCζ activity in the DF region. To verify that the 70kDa band was phosphorylated PKCζ, lysates (mixed UF and DF samples) were treated with lambda phosphatase (+PO4tase) or a blocking peptide (+Peptide). Densitometric quantification of phospho-PKCζ (70kDa band) recovered by antiphosphothreonine immunoprecipitation showed 4-fold higher levels in the UF aortic region than in the DF arch (110±19 versus 24±6 AU, P<0.05) (Figure 6B). However, unlike other isoforms of PKC, phosphorylation of PKCζ threonine (Thr) can either activate the kinase or target the protein for degradation, depending on the site of phosphorylation.20 Phosphorylation of Thr410 in the activation loop leads to increased activity whereas phosphorylation of Thr560 promotes degradation. Autoradiographic experiments using mutated PKCζ do not suggest the presence of any other phosphorylation sites in PKCζ.21 The appearance of PKCζ breakdown products22 at 25kDa and 50kDa (▶) in UF lysates but not DF lysates (Figure 6A) suggested that phosphorylation of the enzyme in the UF region was likely occurring at Thr560, the degradative site, rather than in the activation loop site (Thr410). Although no antibody exists for phospho-Thr560, an antibody for phospho-Thr410, the other site of threonine phosphorylation in PKCζ, was used to probe (Figure 6C) the protein lysates precipitated for phosphothreonine in Figure 6A. Levels of phospho-Thr410, a proxy for activated PKCζ, were elevated 4-fold in the aortic arch (DF) (Figure 6D). This is in contrast to the levels of phospho-PKCζ seen in Figure 6A, which implies that the “missing” phosphothreonine in the UF immunoprecipitates is phospho-Thr560. This evidence, although necessarily indirect, suggests that posttranslational destabilization of PKCζ in the UF region of thoracic aorta leads to the observed decreased kinase activity compared with the DF site in the arch.

Figure 6.

Regional differences in the posttranslational modification of PKCζ. A, Protein lysates from the aortic arch (DF) and the thoracic aorta (UF) were immunoprecipitated using an anti-phosphothreonine antibody, followed by PKCζ immunoblotting. Significantly more phosphorylated PKCζ (→) was observed in the thoracic aorta (UF) than in the aortic arch (DF). However, unlike other isoforms of PKC, phosphorylation of PKCζ can target the protein for degradation, observed as breakdown products of 25 kDa and 50 kDa (▶). Before immunoprecipitation PKCζ was equal in all samples (Total PKCζ). To verify the identity of these bands, the lysates were treated with lambda protein phosphatase (+PO4tase) or a blocking peptide (+Peptide). B, Densitometric quantification of phospho-PKCζ (70-kDa band) recovered by anti-phosphothreonine immunoprecipitation showed 4-fold higher levels in the UF aortic region than in the DF arch (110±19 vs 24±6 AU, P<0.05). C, The protein lysates precipitated for phosphothreonine (from A) were then probed with a phospho-specific PKCζ (Thr410) antibody to show phosphorylation of the activation loop. D, More (4-fold) phospho-Thr410 was seen in the arch (DF) than in the thoracic aorta (UF). All measurements are the average of 4 independent samples, except for the Thr410 blot which was measured in duplicate samples. Negative control lanes (−) are bead-only immunoprecipitates. *P<0.05.

Discussion

Endothelial cells with distinct morphologies, ultrastructural features, and specialized functions are distributed throughout the body, with phenotypes matched to the diverse vascular beds in which they reside. However, over the past decade there is a growing realization that more subtle heterogeneities exist within the same artery over shorter length scales.4,7,23 In large arteries, such spatial differences have been linked to the localization of pathological susceptibility. It has been appreciated for more than a century that atherosclerotic lesions develop in regions of arterial geometry that contemporary imaging and mathematical modeling identify as coincident with complex patterns of blood flow. The association of vascular heterogeneity with predisposition to atherogenesis provides an investigative rationale to study the link between the endothelial responsiveness to hemodynamics and athero-susceptibility or protection. Recent studies have demonstrated differential endothelial gene expression linked to putative atherogenic mechanisms both in cultured cell models24 and in vivo/in situ.7,23 The present study extends regional endothelial heterogeneity to the level of the PKC signaling pathway in normal swine aortic endothelium. We show that although the endothelial cells in the aortic arch and the near-adjacent thoracic aorta express the same complement of PKC isozymes, the kinase activity was higher in the DF region, a difference attributable to activation of the atypical isozyme PKCζ. Furthermore, the posttranslational modification of PKCζ in DF diverged from that in UF, with consistent functional consequences. Interestingly, the intracellular localization of the enzyme was unchanged between the 2 regions, suggesting that in endothelial cells obtained from healthy animals the translocation of PKCζ to the plasma membrane, a traditional marker of activation, requires an additional stimulus.

One of the key findings of this study was the difference in posttranslational PKCζ modifications between the 2 regions. In the thoracic aorta (UF), where the PKC activity was lower, enzyme phosphorylation occurred preferentially on Thr560, as inferred by the lack of phosphorylation on Thr410. In contrast, in the aortic arch (DF) PKCζ phosphorylation appeared on Thr410, with low levels of phosphorylation on Thr560. It has been shown that phosphorylation at Thr560 reduces the stability of the enzyme without affecting the kinase activity while phosphorylation of the activation loop (Thr410) confers increased catalytic activity.20 The pattern of PKCζ modifications reported here is fully consistent with these reports. Other groups studying PKCζ processing by caspases have noted that the full-length kinase is degraded as rapidly as it is produced,22 implying tight regulation of this enzyme. Despite the evidence for decreased degradation in the aortic arch (DF), the observed levels of cytoplasmic PKCζ were equal in the 2 regions. We speculate that a portion of the PKCζ in the thoracic arch (UF) remains identifiable on an immunoblot but has lost kinase activity attributable to posttranslational modifications. PKCζ is not the only isozyme controlled through a degradative pathway; other PKC isozymes including PKCδ,25 PKCθ,26 and PKCα27 appear to be regulated by degradation of the enzyme.

The endothelial susceptibility to atherosclerosis and other disease pathologies varies throughout the vasculature. Recent work in our laboratory7 and elsewhere5,28,29 has begun to demonstrate how endothelial cells located in discrete regions exhibit variable phenotypes that may be “primed for disease” by their local environment. Whether hemodynamics in vivo is directly causative for atherosclerotic susceptibility or merely correlated with an alternate mechanism (eg, structural or developmental differences) is unresolved. However, many labs have demonstrated in vitro that shear stress directly influences enzymes, adhesion molecules, receptors, and structural cytoskeleton,30–35 multiple independent promoter elements,34,35 and transcription factors such as NF-κB and Pyk-2.36,37 The Src and MAP kinase pathways are shear-sensitive,38,39 suggesting that extracellular forces elicit gene expression through cytoplasmic signaling cascades. In this context, our findings offer a glimpse into how endothelial cells can respond differently when biochemical stimuli are superimposed on a diverse hemodynamic environment.

A useful and important methodology for understanding localized effects on the vascular endothelium is to study the cells in their natural environment. In contrast to cells studied in culture, the endothelial cells in this study were maintained until analysis in their natural setting exposed to physical forces such as shear, tension and pressure, cell-cell interactions with smooth muscle cells and circulating cells, and to soluble factors from both the blood and the adjacent tissue. However, the study of discrete in situ areas also presents experimental difficulties relating to the small amount of material with which to work. In this study these limitations were most apparent in 2 areas. First, because only the detergent-soluble cell fraction yielded enough material to study, we were unable to measure PKC abundance and activity in insoluble fractions. Although confocal imaging does not lead us to believe that there is significant PKCζ translocation to the cell membrane or nucleus in either aortic region, it remains possible that the regulation of PKCζ is spatially heterogeneous within the cell. Second, the limited sample material precludes the direct analysis of PKCζ phosphorylation by mass spectrometry. Although we were able to show differential phosphorylation of Thr410, the evidence for the converse regulation of Thr560 is predicated on the hypothesis that there are only 2 sites of threonine phosphorylation in PKCζ. Although this is consistent with all published reports, mass spectrometry would conclusively demonstrate the presence or absence of alternative phospho-sites. Despite these limitations, we believe that measurements of endothelial heterogeneity derived directly from the in vivo state are of high value.

The association of increased endothelial PKCζ activity with a site of increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis may reflect the function of this isozyme in endothelial cells. Genetic disruption of PKCζ in mice has been found to impair NF-κB activation,40 leading us to speculate that the heterogeneity of PKCζ activity observed in this study may contribute to the upregulation of NF-κB pathway elements, which we have previously observed in the DF region.7 The activity of PKCζ has also been shown to regulate thrombin-induced vascular permeability changes.41 This is also consistent with our findings; regions with disturbed flow are well known to have increased permeability to macromolecules such as protein and lipids. Javaid et al reported that PKCζ phosphorylation of ICAM-1 was necessary for receptor clustering and subsequent leukocyte binding.42 This is again consistent with a mechanism by which locally increased PKCζ activity contributes to the atherosclerotic phenotype. Because of the vast number of potential targets, we have begun a proteomics-based approach to characterize the downstream PKCζ targets. Comprehensive identification of PKCζ substrates will allow us to better understand how the differential regulation of PKCζ presented in this study is affecting the endothelial phenotype and the susceptibility to atherosclerosis.

In summary, we identify differences in PKC activity of endothelial cells from adjacent sites that are differentially susceptible to atherosclerosis and experience different hemodynamic environments. In addition to improved understanding of the normal-to-pathology transition, an understanding of the differences that account for susceptibility and protection may identify biomarkers predictive of disease transition and progression, and potential targets for novel pharmaceutical interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HL36049 (MERIT), HL70128, and HL62250 (PFD); and HL07954 and HL80867 (RM). We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Jasmin Lau and Justin Walker and thank Drs Marcelo Kazanietz and Rick Assoian at the University of Pennsylvania for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ku DN, Giddens DP, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis. 1985;5:293–302. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.5.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–560. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, Pober JS, Wick TM, Konkle BA, Schwartz BS, Barnathan ES, McCrae KR, Hug BA, Schmidt AM, Stern DM. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies PF, Polacek DC, Handen JS, Helmke BP, DePaola N. A spatial approach to transcriptional profiling: mechanotransduction and the focal origin of atherosclerosis. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:347–351. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi JT, Chang HY, Haraldsen G, Jahnsen FL, Troyanskaya OG, Chang DS, Wang Z, Rockson SG, Van De Rijn M, Botstein D, Brown PO. Endothelial cell diversity revealed by global expression profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10623–10628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1434429100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim YC, Garcia-Cardena G, Allport JR, Zervoglos M, Connolly AJ, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Luscinskas FW. Heterogeneity of endothelial cells from different organ sites in T-cell subset recruitment. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64293-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passerini AG, Polacek DC, Shi C, Francesco NM, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Pritchard WF, Powell S, Chang GY, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothelial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2482–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305938101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmons CA, Grant GR, Manduchi E, Davies PF. Spatial heterogeneity of endothelial phenotypes correlates with side-specific vulnerability to calcification in normal porcine aortic valves. Circ Res. 2005;96:792–799. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161998.92009.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omi H, Okayama N, Shimizu M, Fukutomi T, Imaeda K, Okouchi M, Itoh M. Statins inhibit high glucose-mediated neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion through decreasing surface expression of endothelial adhesion molecules by stimulating production of endothelial nitric oxide. Microvasc Res. 2003;65:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(02)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoguchi T, Li P, Umeda F, Yu HY, Kakimoto M, Imamura M, Aoki T, Etoh T, Hashimoto T, Naruse M, Sano H, Utsumi H, Nawata H. High glucose level and free fatty acid stimulate reactive oxygen species production through protein kinase C–dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase in cultured vascular cells. Diabetes. 2000;49:1939–1945. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vielma SA, Krings G, Lopes-Virella MF. Chlamydophila pneumoniae induces ICAM-1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells via protein kinase C-dependent activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ Res. 2003;92:1130–1137. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074001.46892.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou MM, Hou W, Johnson J, Graham LK, Lee MH, Chen CS, Newton AC, Schaffhausen BS, Toker A. Regulation of protein kinase C zeta by PI 3-kinase and PDK-1. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mochly-Rosen D, Gordon AS. Anchoring proteins for protein kinase C: a means for isozyme selectivity. Faseb J. 1998;12:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu YL, Chien S. Effects of shear stress on protein kinase C distribution in endothelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:237–249. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traub O, Monia BP, Dean NM, Berk BC. PKC-epsilon is required for mechano-sensitive activation of ERK1/2 in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31251–31257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerbon J, del Carmen Lopez-Sanchez R. Diacylglycerol generated during sphingomyelin synthesis is involved in protein kinase C activation and cell proliferation in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Biochem J. 2003;373:917–924. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowling N, Walsh RA, Song G, Estridge T, Sandusky GE, Fouts RL, Mintze K, Pickard T, Roden R, Bristow MR, Sabbah HN, Mizrahi JL, Gromo G, King GL, Vlahos CJ. Increased protein kinase C activity and expression of Ca2+-sensitive isoforms in the failing human heart. Circulation. 1999;99:384–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hecker M, Luckhoff A, Busse R. Modulation of endothelial autacoid release by protein kinase C: feedback inhibition or non-specific attenuation of receptor-dependent cell activation? J Cell Physiol. 1993;156:571–578. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041560317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seynaeve CM, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Sausville EA, Worland PJ. Differential inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by UCN-01, a staurosporine analogue. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Good JA, Brindley DN. Molecular mechanisms regulating protein kinase Czeta turnover and cellular transformation. Biochem J. 2004;378:83–92. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Standaert ML, Sajan MP, Miura A, Kanoh Y, Chen HC, Farese RV, Jr, Farese RV. Insulin-induced activation of atypical protein kinase C, but not protein kinase B, is maintained in diabetic (ob/ob and Goto-Kakazaki) liver. Contrasting insulin signaling patterns in liver versus muscle define phenotypes of type 2 diabetic and high fat-induced insulin-resistant states. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24929–24934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith L, Chen L, Reyland ME, DeVries TA, Talanian RV, Omura S, Smith JB. Activation of atypical protein kinase C zeta by caspase processing and degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40620–40627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908517199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajra L, Evans AI, Chen M, Hyduk SJ, Collins T, Cybulsky MI. The NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway in aortic endothelial cells is primed for activation in regions predisposed to atherosclerotic lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9052–9057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topper JN, Gimbrone MA., Jr Blood flow and vascular gene expression: fluid shear stress as a modulator of endothelial phenotype. Mol Med Today. 1999;5:40–46. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava J, Procyk KJ, Iturrioz X, Parker PJ. Phosphorylation is required for PMA- and cell-cycle-induced degradation of protein kinase Cdelta. Biochem J. 2002;368:349–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heissmeyer V, Macian F, Im SH, Varma R, Feske S, Venuprasad K, Gu H, Liu YC, Dustin ML, Rao A. Calcineurin imposes T cell unresponsiveness through targeted proteolysis of signaling proteins. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:255–265. doi: 10.1038/ni1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leontieva OV, Black JD. Identification of two distinct pathways of protein kinase Calpha down-regulation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5788–5801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh P, Li Y, Yu J, Durr E, Krasinska KM, Carver LA, Testa JE, Schnitzer JE. Subtractive proteomic mapping of the endothelial surface in lung and solid tumours for tissue-specific therapy. Nature. 2004;429:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature02580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aird WC, Edelberg JM, Weiler-Guettler H, Simmons WW, Smith TW, Rosenberg RD. Vascular bed-specific expression of an endothelial cell gene is programmed by the tissue microenvironment. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1117–1124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagase M, Abe J, Takahashi K, Ando J, Hirose S, Fujita T. Genomic organization and regulation of expression of the lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor (LOX-1) gene. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33702–33707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chappell DC, Varner SE, Nerem RM, Medford RM, Alexander RW. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates adhesion molecule expression in cultured human endothelium. Circ Res. 1998;82:532–539. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagel T, Resnick N, Atkinson WJ, Dewey CF, Jr, Gimbrone MA., Jr Shear stress selectively upregulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:885–891. doi: 10.1172/JCI117410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dewey CF, Bussolari SR, Gimbrone MA, Davies PF. The dynamic response of vascular endothelial cells to fluid shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1981;103:177–185. doi: 10.1115/1.3138276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khachigian LM, Resnick N, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Collins T. Nuclear factor-kappa B interacts functionally with the platelet-derived growth factor B-chain shear-stress response element in vascular endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1169–1175. doi: 10.1172/JCI118106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magid R, Murphy TJ, Galis ZS. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in endothelial cells is differentially regulated by shear stress. Role of c-Myc. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32994–32999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai LK, Okuda M, Abe J, Yan C, Berk BC. Fluid shear stress activates proline-rich tyrosine kinase via reactive oxygen species-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1790–1796. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000034475.40227.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lan Q, Mercurius KO, Davies PF. Stimulation of transcription factors NF kappa B and AP1 in endothelial cells subjected to shear stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:950–956. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis ME, Cai H, Drummond GR, Harrison DG. Shear stress regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression through c-Src by divergent signaling pathways. Circ Res. 2001;89:1073–1080. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jo H, Sipos K, Go YM, Law R, Rong J, McDonald JM. Differential effect of shear stress on extracellular signal-regulated kinase and N-terminal Jun kinase in endothelial cells. Gi2- and Gbeta/gamma-dependent signaling pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:1395–1401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leitges M, Sanz L, Martin P, Duran A, Braun U, Garcia JF, Camacho F, Diaz-Meco MT, Rennert PD, Moscat J. Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;8:771–780. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Hahn CN, Parsons M, Drew J, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. Role of protein kinase Czeta in thrombin-induced endothelial permeability changes: inhibition by angiopoietin-1. Blood. 2004;104:1716–1724. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Javaid K, Rahman A, Anwar KN, Frey RS, Minshall RD, Malik AB. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces early-onset endothelial adhesivity by protein kinase Czeta-dependent activation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Circ Res. 2003;92:1089–1097. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000072971.88704.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.