Abstract

Study Objective

Sexual reference display on a social networking web site (SNS) is associated with self-reported sexual intention; females are more likely to display sexually explicit content on SNSs. The purpose of this study was to investigate male college students' views towards sexual references displayed on publicly available SNSs by females.

Design

Focus groups

Setting

One large state university

Participants

Male college students age 18–23

Interventions

All tape recorded data was fully transcribed, then discussed to determine thematic consensus.

Main Outcome Measures

A trained male facilitator asked participants about views on sexual references displayed on SNSs by female peers and showed examples of sexual references from female's SNS profiles to facilitate discussion.

Results

A total of 28 heterosexual male participants participated in 7 focus groups. Nearly all participants reported using Facebook to evaluate potential female partners. Three themes emerged from our data. First, participants reported that displays of sexual references on social networking web sites increased sexual expectations. Second, sexual reference display decreased interest in pursuing a dating relationship. Third, SNS data was acknowledged as imperfect but valuable.

Conclusion

Females who display sexual references on publicly available SNS profiles may be influencing potential partners' sexual expectations and dating intentions. Future research should examine females' motivations and beliefs about displaying such references, and educate women about the potential impact of these sexual displays.

Keywords: Adolescent, sexual behavior, internet, social networking sites, college student

INTRODUCTION

Social networking web sites (SNSs) are extremely popular among college students, over 94% of college students currently maintain a SNS profile.[1, 2] SNSs are commonly used to initiate and maintain friendships, and anecdotal reports suggest that college students may also use SNSs to evaluate potential romantic partners.[2, 3] College students display a variety of personal information on SNS profiles, including the profile owner's sexual preference, whether the profile owner is currently in a romantic relationship and displayed sexual references.[4–8] The definition of sexual references on SNSs includes sexually explicit material or discussions about sexual behaviors.[9] On SNS profiles, these references can include photographs portraying the profile owner in a sexually suggestive way or personal descriptions of sexual experiences.[4, 5]

Females are more likely than males to display sexual references on a SNS profile.[5] Our recent work evaluated whether sexual reference display on a public SNS was associated with sexual intention, sexual experience or risky sexual behavior. We found that among older adolescents, display of sexual references on a SNS was associated with sexual intention.[10] If these sexual references are interpreted by viewers as messages of sexual intention, then these references may influence the sexual expectations of potential romantic partners who view the SNS profile.

While sexual behavior among college students is common, it is not without potential for negative consequences.[11] Rates of sexual activity among adolescent and young adult males and females are comparable, but the potential negative consequences of sexual behavior such as unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are disproportionately distributed among females.[12, 13] Female college students are also more likely to be victims of sexual assault or sexual coercion compared to male peers.[12]

This study focuses on female college students because females are more at risk for negative consequences associated with sex, and females are more likely to display sexual references on their SNS profiles.[12] Our goal for this preliminary investigation was to investigate male college students' views towards sexual references displayed on publicly available SNSs by females.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Between July and September 2009 participants were recruited through purposeful sampling at a large state university. Eligible subjects were current undergraduate students who were male and interested in dating females. A trained male facilitator identified key contacts within university housing and several campus organizations with the goal of recruiting males from a variety of social groups. The facilitator informed the key contacts on the objectives of the research. The key contact then recruited 2–3 male peers to accompany him to the focus group. All individuals who attended the focus groups and met the eligibility requirements participated. Each participant gave written consent for participation. Participants received a meal and a $15 gift card for participating. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board approved this project.

Focus groups

A trained male facilitator conducted semi-structured focus groups. Focus groups were designed to explore male college students' views and interpretations of sexual references displayed on female college students' SNS profiles. Focus groups were the optimal method to investigate this topic as they allow for participant interaction and encourage participants to build on other's comments, which leads to greater insight into why certain opinions or views are held. However, given that sexual discussions are an intimate topic, relatively small (3–4 participants) focus groups were used to create an atmosphere in which participants could comfortably discuss such a topic.

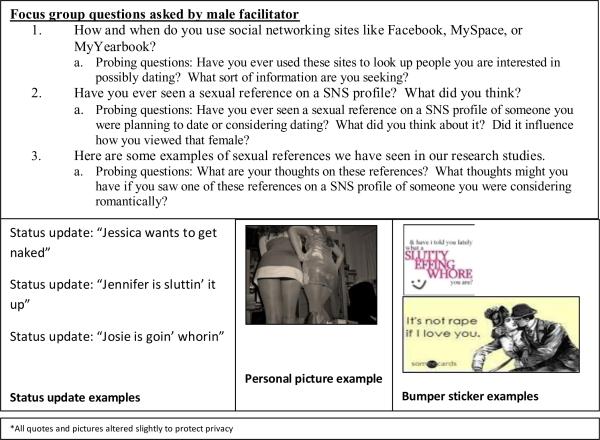

Before the start of each focus group, participants provided their age in years. The facilitator then introduced the project and explained the purpose of the focus group. Male participants were encouraged to discuss their thoughts and interpretations of displayed sexual references on college females' SNS profiles. The facilitator began with open-ended questions followed by probing questions. Participants were initially asked to discuss their experiences with SNSs and their interpretations of displayed SNSs sexual references. Later during the group, participants were shown examples of sexual references drawn from SNSs used in our ongoing research studies and asked to comment on them. Figure 1 provides the list of questions used in each focus group, as well as examples of sexual references that were shown to participants in each focus group to generate discussion. These references included data from Facebook status updates (personally written text that typically describes the profile owner's actions, emotions, or plans), personal photographs, and bumper stickers (downloaded icons displayed on SNS profiles). Each focus group lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. All focus group discussions were audio recorded and transcribed.

Figure 1.

Focus group questions and example references shown to participants during focus groups

Analysis

All transcripts were read and coded by three authors with expertise in adolescent sexual relationships and behaviors for themes present in the data. Transcribed data from each focus group was first analyzed separately, after which a merged document of themes and corresponding text was created in the grounded theory tradition.[14–16] Investigators discussed and reached consensus among major themes in the data and determined illustrative quotations.

RESULTS

A total of 28 heterosexual males participated in seven focus groups. All participants contributed to discussions. All participants reported maintaining a personal profile on either MySpace or Facebook, and a few participants reported maintaining personal profiles on both of these SNSs. Most participants reported logging into their profile daily and a few reported logging in every few days.

All participants reported having seen sexual references displayed on SNS profiles by female college students. Participants gave consistent descriptions of what they considered to be sexual references, such as photographs with nudity or revealing clothing, sexually suggestive poses, or text describing sexual behaviors.

Participants commented that within a SNS profile, certain types of references are viewed as being more representative of a person's character, and therefore weighed more heavily when evaluating someone. Bumper stickers were unanimously considered the least personal or believable type of information on Facebook, “bumper stickers are intended to be pretty funny, at least that's how I use them.” A few participants mentioned that often these icons are sent to a profile owner by another SNS user, so the bumper sticker may represent a friends' humor or values more than the profile owner's personal views. One participant explained that he did not know how to remove bumper stickers from his profile, so any bumper sticker sent to him was permanently displayed on his profile, not necessarily by choice. Status updates were often considered reliable representations of a profile owner, but participants did not always agree on the meaning of the status update. For example, the status update example presented to the focus groups that referred to “goin whorin” generated two opposite reactions from participants in one group. One participant stated, “well you can just tell that she's a whore.” However, another participant argued, “you don't clearly know what that person's definition of the word is. I mean yeah, but like whore could be like obviously what pops into mind first or it could be like I don't know like going out and having a good time, like shock factor.” Participants all agreed that personal pictures were considered the most valuable in assessing someone one didn't know well, “apicture kind of speaks a thousand words, you know?”

Three themes were identified in our data: 1) sexual reference display increased sexual expectations, 2) sexual reference display decreased interest in pursuing a dating relationship and 3) SNS data was acknowledged as imperfect but valuable.

Theme 1: Sexual reference display increased sexual expectations

The most consistent theme expressed during focus groups was that displays of sexual references on SNS profiles were interpreted as messages that sexual activity may be forthcoming. Increased numbers of references, such as multiple photographs in revealing clothing, were considered particularly convincing clues that a romantic encounter with the female profile owner would lead to sexual activity.

“…it would definitely make me think a little bit, um I mean if that's someone I was looking to date. It might be a little easier to get her naked than somebody else.”

“I guess if they were willing to put it up on Facebook, then they would probably be willing to give it to me.”

“Sexual pictures equal sexual activity is around the corner.”

“Yeah, the sexier the pictures, the more you know they are wilder.”

A few participants expressed that though they felt that a sexual reference display suggested increased potential for sexual activity with a female, this display could lead to a diminished interest in sexual activity with that female.

“I think [sexual references] are an indication of how easy it would be to get with that person, you know, or whatever. Um, that would probably increase the indication of the availability of that, but it doesn't mean that would increase my wanting of that.”

Theme 2: Sexual reference display decreased interest in pursuing a dating relationship

Several men described using Facebook to investigate potential romantic partners; one participant explained: “I have looked at people's interests, photos, friends, and things to see maybe if I am more or less interested [in dating them].”

Many male participants discussed the impact of viewing displayed SNS references on their consideration of the female profile owner as a potential dating or relationship partner. Several acknowledged that displayed sexual references could negatively impact their views towards that female as a relationship partner. Participants commented that seeing a trend of multiple sexual references was more concerning than seeing a single concerning reference.

“If that girl is just kind of putting herself out there for anybody to see, uh, that's not really somebody I would want to date. I mean, I think for me, keeping that stuff private is a little bit better.”

“If they don't mind people seeing them online then why wouldn't they mind people seeing that in real life and that's something I wouldn't want to deal with if I was going to date that person.”

“Yeah, I can think of a few instances where it changed my mind [about whether to date that woman].”

“I don't want to show my friends a girl I like on Facebook and them seeing only sexual pictures and her all drunk.”

“Well you can see how flirtatious they are with other guys in photos and by what people have written about them which can be a deterrent, you know?”

“I don't want to be with someone who puts themselves out there so much.”

“I want someone who is loyal and I feel like someone who puts themselves out there in pictures might have questionable morals.”

Theme 3: SNS data was acknowledged as imperfect but valuable

Participants expressed complex and varied viewpoints about the accuracy of personal information displayed on SNSs. One expressed viewpoint was that any information presented on Facebook may not be a perfect representation of that person, as it was felt that people may embellish or misrepresent themselves on SNSs. A second expressed viewpoint was that SNS displays represented people's character and personality and could be believed. Participants further explained that if the profile owner is not known very well, then SNS data is considered the best available data about that person. In these cases, the SNS becomes a way to form first impressions of people one doesn't know very well. Several participants also explained that if the profile owner is a friend, and the SNS data supports what they already believe about that friend, then the profile is assumed to be a true representation.

A few participants seemed to struggle with this topic and expressed both a questioning of displayed information as well as an example of a decision based on displayed information from SNS profiles. These comments suggested that although participants believed that the displayed information could be suspect, they still made decisions or took action based on this information.

“So I think this [display] would be another deterrent [to dating this girl]. Although I wouldn't judge a person completely off of it.”

“At this point I would say they depend more on real life, but what I see in Facebook can change things.”

In processing the complex information presented on SNSs, participants described tools they use in interpreting displayed information. As in Theme 2, participants commonly mentioned noting frequency patterns in display of sexual references to assist them in drawing conclusions about a potential romantic partner.

“Like nights out on the town, I've seen girls on Halloween they're dressed up in a promiscuous costume or something like that, you know. If there's multiple numbers of pictures like that that starts to be a huge indicator. Like different nights out, but like, slutty outfits.”

“I think that, there's a point where if you see kind of a trend you could definitely figure out…it's a good indicator.”

Last, participants acknowledged that unconscious processes may be triggered by viewing sexual references, and that these unconscious thoughts could impact their view of the female who displays references.

“I mean I'm not passing complete judgment on the person but you can kind of like I said, I think a lot has to do with the subconscious stereotypes you pass on a person.”

“I don't think I would ever rely on Facebook to give me a good, great snapshot of what the person's all about but I mean, I think definitely it subconsciously probably makes an impression, whether it's true or not.”

“I think more of when it kind of has a subconscious influence on you is when you don't know the person. Maybe you're looking at some of their friends or something um when you don't even know the person at all, that's when you kind of get those stereotypes put in your head.”

DISCUSSION

Our study provides a preliminary assessment of how male college students view sexual references displayed on female peers' SNS profiles. The dominant theme of our data was that males reported that displayed sexual references by females on SNSs may increase their sexual expectations of these females. Several males were openly willing to discuss these increased sexual expectations during our focus groups. However, others did not openly admit to this increased expectation and instead discussed these references as having a “subconscious” influence.

Our finding that display of sexual references on SNSs by females is associated with increased expectations for sexual behavior by males must be interpreted with care. Two points are essential to consider. First, though our previous work suggests that display of sexual references on SNSs is associated with reporting intention to intiate sexual behavior, those findings do not imply that all females place sexual references on SNSs as a direct expression of sexual intention. Second, though our current findings suggest that displayed sexual references may influence sexual expectations, not all males in our study expressed this viewpoint, and even among those that did it is unlikely that all would act on these increased expectations.

Despite these considerations, our findings raise concerns as it is not known how sexual expectations actually influence sexual behavior. As display of sexual references is associated with sexual intentions, and display of sexual references is associated with increased expectations for sexual behavior by partners, then displayed sexual references may lead to increased likelihood of sex. Increased number of sexual partners is associated with increased risks for STIs; female adolescents have the highest rates of STIs in the US.[13, 17] Given the mens' dialogue suggesting that such displays increase expectations for sexual activity, it is possible that sexual references displayed by females could serve as a risk factor for unwanted sexual advances by males.

The second theme in our data suggests that for some men in our study, displayed sexual references led to diminished interest in dating these women. The men described concerns about losing social capital among friends by dating a woman with publicly available sexual references. This raises the concern that the display of sexual references may lead a female to attract males who are interested in sexual activity but not necessarily in romantic relationships. Alternatively, these statements may represent social scripting, that males offer this information because they feel it is the right thing to say in this context.[18]

Our last and most complex theme from this data illustrated the opinions among males regarding whether information presented on SNSs represents reality. Despite a general recognition that not all information displayed on a profile may be accurate, participants acknowledged the powerful impact of SNSs, especially in creating first impressions. Participants described systems through which displayed sexual references were filtered, both conscious and subconscious. Sexual references appear to be able to generate powerful impressions, ones that could make “subconscious impressions” even if a viewer tries to ignore the content, and potentially call to mind “stereotypes” about women. The potential for negative consequences from gender stereotypes has been illustrated in multiple domains including sexual relationships as well as career advancement.[19, 20] Our findings support previous work that suggest that SNS profiles have potential risks for female sexual objectification.[21]

There are several limitations to our study which merit attention. Our study utilized a purposeful sample, which is common in focus group studies. Although we made every effort to seek a sample that would represent a range of male college students by recruiting from a variety of campus organizations, generalization to the larger adolescent population should be done with caution. Further, our study focused on views from heterosexual males, future research should evaluate the impact of displayed sexual references on adolescents of both genders and other sexual preferences. Social desirability may have also influenced responses of our participants, particularly given the intimate nature of this topic. Our study utilized smaller focus groups in an attempt to limit such bias.

In conclusion, participants all reported use of SNSs, and many participants acknowledged using these web sites to investigate potential romantic partners. Therefore, the content of these web sites is being used by college students to inform decisions about not only friendships, but also romantic relationships. Given the popularity of SNSs and the high prevalence of sexual references displayed on SNSs, these references have the potential to influence sexual expectations among a large population of college students. Though male college students recognize the complexity of obtaining personal information via SNSs, they still acknowledge the power of displayed sexual references. If male college students are aware that these displays may impact their sexual expectations and lead to stereotyped views of females, then female college students should be aware of this as well. It is possible that sexual education programs should include messages about the impact of sexual references on SNSs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work described was supported by award K12HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Child Health, Behavior and Development Institute. The authors would also like to thank Elizabeth Cox, MD, PhD; Henry Young, PhD and Molly Carnes, MD, MS for their assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The Taste for Privacy: An Analysis of College Student Privacy Settings in an Online Social Network. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008;14(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capitol and College Students' Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenhart A, Madden M. Social Networking Sites and Teens: An Overview. Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno MA, Parks M, Richardson LP. What are adolescents showing the world about their health risk behaviors on MySpace? MedGenMed. 2007;9(4):9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno MA, et al. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and Associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno MA, et al. Reducing at-risk adolescents' display of risk behavior on a social networking web site: a randomized controlled pilot intervention trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008;31(1):125–46. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams AL, Merten MJ. A Review of Online Social Networking Profiles by Adolescents: Implications for Future Research and Intervention. Adolescence. 2008;43:253–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunkel D, et al. Sex on TV 4. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno MA, et al. A Pilot Investigation of Sexual Reference Display on Facebook: Are These References Associated with Sexual Intention, Sexual Experience or Risky Sexual Behavior? Manuscript under review. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire E, 3rd, et al. Sexual behavior, knowledge, and attitudes about AIDS among college freshmen. Am J Prev Med. 1992;8(4):226–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association ACH. American College Health Association: National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Data Report Fall 2008. American College Health Association; Baltimore: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton DK, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glesne C. Becoming Qualitative Researchers. Second ed. Longman; Reading, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser BG, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Transaction; Hawthorne, NY: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coker AL, et al. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. J Sch Health. 1994;64(9):372–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiederman MW. The Gendered Nature of Sexual Scripts. The Family Journal. 2005;13(4):496–502. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilman M. Description and Prescription: How Gender Stereotypes prevent women's ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, Gender, Hierarchy and Leadership. 2001;57:657–674. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muehlenhard C, Hollabaugh L. Do women sometimes say no when they mean yes? The prevalence and correlates of women's token resistance to sex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:872–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manago AM, et al. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:446–458. [Google Scholar]