Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric disorder of complex pathogenesis caused by acute or chronic liver failure. We investigated the effects of cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive constituent of Cannabis sativa with anti-inflammatory properties that activates the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 5-HT1A, on brain and liver functions in a model of hepatic encephalopathy associated with fulminant hepatic failure induced in mice by thioacetamide.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Female Sabra mice were injected with either saline or thioacetamide and were treated with either vehicle or cannabidiol. Neurological and motor functions were evaluated 2 and 3 days, respectively, after induction of hepatic failure, after which brains and livers were removed for histopathological analysis and blood was drawn for analysis of plasma liver enzymes. In a separate group of animals, cognitive function was tested after 8 days and brain 5-HT levels were measured 12 days after induction of hepatic failure.

KEY RESULTS

Neurological and cognitive functions were severely impaired in thioacetamide-treated mice and were restored by cannabidiol. Similarly, decreased motor activity in thioacetamide-treated mice was partially restored by cannabidiol. Increased plasma levels of ammonia, bilirubin and liver enzymes, as well as enhanced 5-HT levels in thioacetamide-treated mice were normalized following cannabidiol administration. Likewise, astrogliosis in the brains of thioacetamide-treated mice was moderated after cannabidiol treatment.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Cannabidiol restores liver function, normalizes 5-HT levels and improves brain pathology in accordance with normalization of brain function. Therefore, the effects of cannabidiol may result from a combination of its actions in the liver and brain.

Keywords: hepatic encephalopathy, cannabidiol, cognition, liver enzymes, thioacetamide

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a syndrome observed in patients with end-stage liver disease. It is defined as a spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities in patients with liver dysfunction, after exclusion of other known brain diseases, and is characterized by personality changes, intellectual impairments and a depressed level of consciousness associated with multiple neurotransmitter systems, astrocyte dysfunction and cerebral perfusion (Riggio et al., 2005; Magen et al., 2008; Avraham et al., 2006; 2008a; 2009; Butterworth, 2010). Subtle signs of HE are observed in nearly 70% of patients with cirrhosis and approximately 30% of patients dying of end-stage liver disease experience significant encephalopathy (Ferenci, 1995). HE, accompanying the acute onset of severe hepatic dysfunction, is the hallmark of fulminant hepatic failure (FHF), and patients with HE have been reported to have elevated levels of ammonia in their blood (Stahl, 1963). In addition, the infiltration of tumour necrosis factor-α-secreting monocytes into the brain of bile duct-ligated mice, a model of chronic liver disease, has been found 10 days after the ligation, indicating that neuroinflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of HE. This infiltration was shown to be associated with activation of the cerebral endothelium and an increase in the expression of adhesion molecules (Kerfoot et al., 2006).

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a non-psychoactive ingredient of Cannabis sativa (Izzo et al., 2009). Many mechanisms have been suggested for its action, such as agonism of 5-HT1A receptors (Russo et al., 2005). It also has a very strong anti-inflammatory activity both in vivo, as an anti-arthritic therapeutic (Malfait et al., 2000; Durst et al., 2007), and in vitro, manifested by inhibition of cytokine production in immune cells (Ben-Shabat et al., 2006). The finding that CBD is devoid of any psychotropic effects combined with its anti-inflammatory activity makes it a promising tool for treating HE, which is exacerbated by an inflammatory response (Shawcross et al., 2004). In the present work, we aimed to explore the effects of CBD in the acute model of HE induced by the hepatotoxin thioacetamide (TAA), focusing on brain function, brain pathology and 5-HT levels, liver function and pathology as possible targets for therapeutic effects of CBD.

Methods

Mice

Female Sabra mice (34–36 g), 8 to 10 weeks old, were assigned at random to different groups of 10 mice per cage and were used in all experiments. All cages contained wood-chip bedding and were placed in a temperature-controlled room at 22°C, on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07h00min). The mice had free access to water 24 h a day. The food provided was Purina chow and the animals were maintained in the animal facility (Specific Pathogen Free Organism unit) of the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem. Mice were killed after each treatment by decapitation between 10h00min and 12h00min. Animals were kept at the animal facility in accordance with NIH guidelines and all experiments were approved by the institutional animal use and care committee, No. MD-89.52-4.

Induction of hepatic failure

We adapted the rat model of acute liver failure induced by TAA to mice (Zimmermann et al., 1989). The TAA model in mice has been extensively validated previously (Honda et al., 2002; Fernández-Martínez et al., 2004; Schnur et al., 2004). TAA was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Rehovot, Israel) in powder form and dissolved in sterile normal saline (NS) solution; it was injected i.p. as a single dose of 200 mg·kg−1. Vehicle (NS) was also administered in a separate group of animals that served as controls. Twenty-four hours after injection of TAA all animals (including control) were injected s.c. with 0.5 mL of a solution containing 0.45% NaCl, 5% dextrose and 0.2% KCl in order to prevent hypovolaemia, hypokalaemia and hypoglycaemia. The mice were intermittently exposed to infrared light in order to prevent hypothermia.

Administration of CBD

CBD was extracted from cannabis resin (hashish) and purified as previously reported (Gaoni and Mechoulam, 1971) and was dissolved in a vehicle solution consisting of ethanol, emulphor and saline at a ratio of 1:1:18, respectively, and was injected in a single dose of 5 mg·kg−1 i.p, 1 day after either NS or TAA treatment. Similarly, the CBD-related vehicle (the same mixture without CBD) was administered at the same time points following either NS or TAA treatment. A dose of 5 mg·kg−1 CBD was chosen based on the studies done by Magen et al. (2009; 2010;) and on preliminary experiments done in our laboratory, which demonstrated that this does produced a maximal effect compared to 1 and 10 mg·kg−1. Four groups of animals were studied: control naïve animals treated with either CBD or its vehicle, and corresponding TAA-treated animals.

Assessment of neurological function

Neurological function was assessed by a 10-point scale based on reflexes and task performance (Chen et al., 1996): exit from a 1 m in diameter circle in less than 1 min, seeking, walking a straight line, startle reflex, grasping reflex, righting reflex, placing reflex, corneal reflex, maintaining balance on a beam 3, 2 and 1 cm in width, climbing onto a square and a round pole. For each task failed or abnormal reflex reaction a score of 1 was assigned. Thus, a higher score indicates poorer neurological function. The neurological score was assessed 1 day after induction of hepatic failure by TAA (day 2). The mice were then divided between treatment groups so that all groups had similar baseline neurological scores after TAA induction. The post-treatment neurological score was assessed 1 day after administration of CBD or vehicle (day 3).

Assessment of activity

The activity test was performed 2 days after the induction of hepatic failure. Activity of two mice was measured simultaneously for a 5 min period. Two mice were tested together to lower stress to the minimum, as it has been shown that separation of mice induces stress (van Leeuwen et al., 1997; Hao et al., 2001). Activity was assessed in the open field (20 × 30 cm field divided into 12 squares of equal size) as described previously (Fride and Mechoulam, 1993). Locomotor activity was recorded by counting the number of crossings by the mice at 1 min intervals.

Results are presented as the mean number of crossings·min−1.

Cognitive function

Cognitive function studies were performed 8 days after the induction of hepatic failure. The animals were placed in an eight-arm maze, which is a scaled-down version of that developed for rats (Olton and Samuelson, 1976; Pick and Yanai, 1983). Mice were deprived of water 2 h prior to the test and a reward of 50 µL of water was presented at the end of each arm, in order to motivate them to perform the task. Animals were divided between treatment groups so that all groups had similar baselines neurological scores after TAA induction. The mice were tested (no. of entries) until they made entries into all eight arms or until they completed 24 entries, whichever came first. Hence, the lower the score the better the cognitive function. Food and water were given at the completion of the test. Maze performance was calculated on each day for five consecutive days. Results are presented as area under the curve (AUC) utilizing the formula: (day 2 + day 3 + day 4 + day 5) − 4*(day 1) (Pick and Yanai, 1983).

Brain histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Two days after the induction of hepatic failure, mice were killed by decapitation and brains were excised and fixed in 4% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde.

The brain was cut along the midline and separated into two pieces containing brain and cerebellum hemispheres. Both sections were embedded en block in paraffin and 6 µm sagittal sections were adhered to slides. Serial sections were taken in 15 groups of slides (10 slides each, three sections per slide) at 100 µm intervals. These slides were used for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry (a total of 90 sections), according to standard protocol. Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in xylene and alcohol solutions, rinsed with tris buffer saline. Citrate buffer (pH 6) was used for antigen retrieval. The endogenous peroxidase was blocked with H2O2 (0.3% in phosphate buffer saline). Sections were then incubated in blocking buffer for 1 h. A series of reselected sections were then treated with primary antibody against GFAP (1:2500, DakoCytomation, Denmark), overnight at 4°C, and then with goat anti-rabbit (1:200, Vector Burligame, CA, USA) as secondary antibody. Immunoreactions were visualized with the avidin–biotin complex (Vectastain) and the peroxidase reaction was visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Vector), as chromogen. Sections were finally counterstained with haematoxylin and examined under light microscope (Zeiss Axioplan 2). Images were captured with a digital camera (NIKON DS-5Mc-L1) mounted on microscope. Astrocytes were evaluated at the hippocampal area of both hemispheres. A total of five to seven randomly selected visual fields per hemisphere section were evaluated. A square with 100 square subdivisions each of 3721 µm2 as defined by an ocular morphometric grid adjusted at the prefrontal lens, was centred at each visual field. The number of GFAP-positive astrocytes·mm−2 was evaluated. Only those cells with an identifiable nucleus were counted. In addition, in an attempt to evaluate the level of activation of the astrocytes (cell size, extension of cell processes) the number of small square subdivisions with a positive GFAP signal and their % of the total number of square subdivisions counted, were calculated.

Two independent observers who were blinded to sample identity performed all quantitative assessments. In cases where significant discrepancies were obvious between the two observers, the evaluation was repeated by a third one.

Liver histopathology

Two days after the induction of hepatic failure, mice were killed by decapitation and their livers were excised and fixed in 4% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde.

Liver histopathological analysis and scoring of necrosis (coagulative, centrilobular) were performed as described previously (Avraham et al., 2008a).

Serum ammonia, liver enzymes and bilirubin levels

Serum for alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), bilirubin and ammonia measurements was obtained on day 3 in glass tubes, centrifuged, and analysed on the day of sampling using a Kone Progress Selective Chemistry Analyzer (Kone Instruments, Espoo, Finland). All serum samples were processed in the same laboratory using the same methods and the same reference values.

5-HT synthesis

On day 12, mice killed by decapitation and their brains were dissected out for determination of 5-HT levels. The assays for 5-HT were performed by standard alumina extraction, and HPLC with electrochemical detection using dehydroxybenzylamine (DHBA) as an internal standard (Avraham et al., 2006).

Experimental design

Experiment 1

On the first day of this experiment, 20 mice were administered with TAA (200 mg·kg−1) and 20 saline. The following day, neurological evaluation was performed and saline-treated and TAA-treated mice were each assigned to two different subgroups with approximately equal neurological score, which were administered either saline or CBD (5 mg·kg−1). On the third day, mice were evaluated for neurological and locomotor function, after which they were killed and their brains and livers were dissected out and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Blood was drawn and separated for plasma, in which liver enzymes were quantified.

Experiment 2

This was identical to experiment 1 on days 1–3, only the mice were not killed on day 3 but were evaluated for cognitive function using the eight-arm maze test, on days 8–12. On day 12, the mice were killed and their livers and brains were dissected out for determination of 5-HT levels.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way anova followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test.

Results

Neurological score

TAA significantly increased the neurological score of mice compared to the control group (Figure 1; one-way anova: F3,29= 43.19, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01). Administration of 5 mg·kg−1 CBD to TAA-treated mice improved the neurological score compared to TAA alone (1 ± 0.15; P < 0.01). CBD did not affect the score of the control animals.

Figure 1.

Neurological function, evaluated 2 days after induction of hepatic failure, was impaired in thioacetamide (TAA) mice and was restored by cannabidiol (CBD). **P < 0.01 versus control, #P < 0.01 versus TAA.

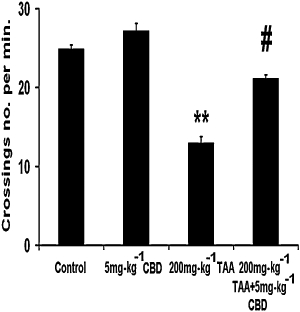

Activity

TAA decreased the activity level of the mice (Figure 2; anova: F3,29= 64.18, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01) and CBD administration significantly increased the activity level in these TAA mice, compared to the untreated TAA mice (P < 0.01). CBD did not affect the activity of control animals.

Figure 2.

Locomotor function, evaluated 3 days after induction of hepatic failure, was decreased in thioacetamide (TAA) mice and was restored by cannabidiol (CBD). **P < 0.01 versus control, #P < 0.01 versus TAA.

Cognitive function

Cognitive function was significantly impaired following TAA exposure, as reflected by the higher AUC values (Figure 3; anova: F3,22= 7.22, P= 0.001; Bonferroni: P < 0.05) and this was improved following CBD administration (P < 0.01 vs. TAA only). CBD did not affect the cognitive function of control animals.

Figure 3.

Cognitive function, tested 8 days after induction of hepatic failure, was impaired following thioacetamide (TAA) and was improved by cannabidiol (CBD). *P < 0.05 versus control, #P < 0.01 versus TAA. AUC, area under the curve.

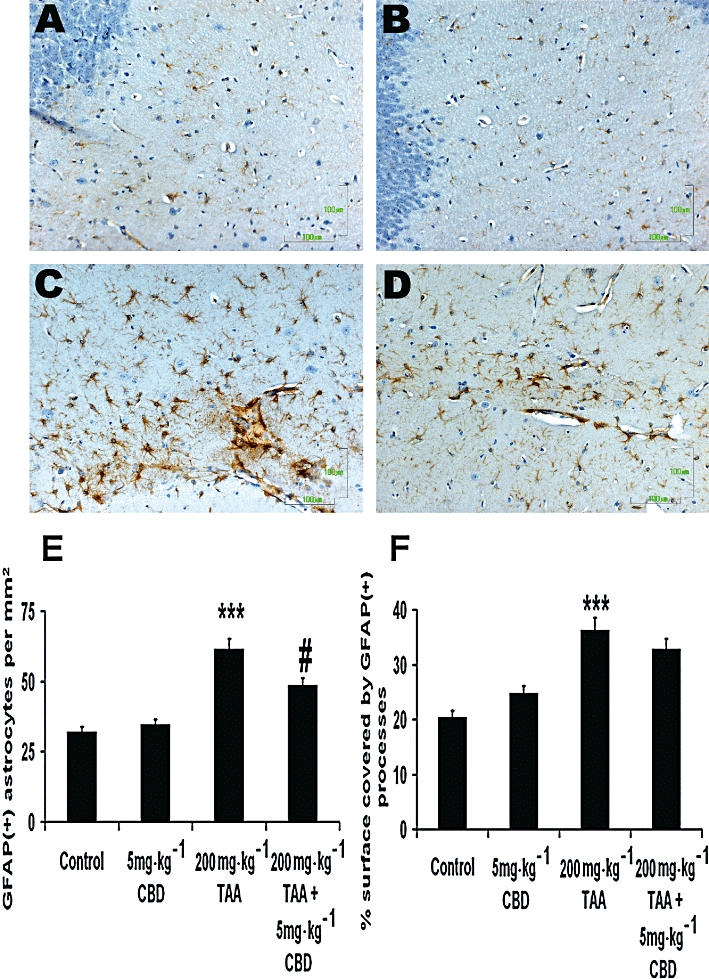

Brain and liver histopathology

Figure 4 shows images of slices from brains of animals from the control group (A), control + CBD group (B), TAA group (C) and TAA + CBD group (D), immunostained for the detection of astrogliosis. Astrogliosis was observed in visual fields studied in TAA animals, as evident both by the increase in the number of GFAP-positive cells·mm−2 (Figure 4E; anova: F3,298= 26.8, P < 0.001; Bonferroni: P < 0.001) and by the increased % of GFAP-positive surface (Figure 4F; anova: F3,298= 19.21, P < 0.001; Bonferroni: P < 0.001). Both parameters were unaffected in CBD-treated controls (Figure 4E and F). However, the number of GFAP-positive cells·mm−2 in TAA + 5 mg·kg−1 CBD-treated animals was reduced compared to TAA-treated animals (Figure 4E; Bonferroni: P= 0.002). In contrast, CBD had no effect on the % of GFAP-positive surface in TAA animals (Figure 4F). Overall, it seems that TAA administration increased the number of activated astrocytes and CBD significantly reduced this effect. However, astrocytes in both CBD- and vehicle-treated TAA animals did not differ as regards their cellular size or extension of processes.

Figure 4.

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry indicating the astrocytic reaction throughout the parahippocampal area in naïve controls (A, B) and thioacetamide (TAA)-treated animals (C,D) following treatment with vehicle (A,C) or cannabidiol (CBD) (B,D). CBD treatment had no effect on the astrocytic activation of naïve animals. However, in the case of animals with hepatic encephalopathy, CBD treatment induced significant reduction in the total number of activated astrocytes, although the level of individual cell activation was not impaired. E. Quantification of GFAP-positive cells·mm−2; the number was reduced in TAA mice treated with 5 mg·kg−1 CBD compared to TAA mice treated with vehicle. ***P < 0.001 versus control, #P < 0.01 versus TAA. F. Quantification of GFAP-positive surface in µm2; 5 mg·kg−1 CBD had no effect on the GFAP-positive surface in the brains of TAA-treated mice. ***P < 0.001 versus control. Scale bars: 100 µm.

TAA-treated animals showed the typical TAA-induced liver necrosis lesions that have been described in detail previously (Avraham et al., 2008a). The statistical analysis of liver histopathology scores did not reveal significant differences in the extent and severity of necrotic lesions between CBD-treated and untreated mice (data not shown).

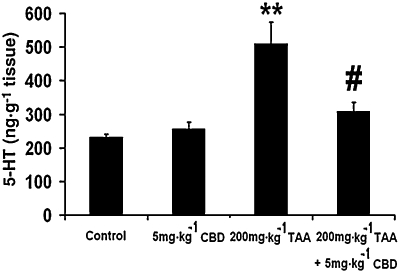

5-HT levels

Whole brain 5-HT levels were increased by TAA administration (Figure 5; anova: F3,17= 13.46, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01), and CBD partially restored the levels in TAA-treated animals (P < 0.01 vs. TAA only). CBD did not affect the levels of 5-HT in control animals.

Figure 5.

Brain 5-HT levels, measured 12 days after induction of hepatic failure, were increased in the brains of thioacetamide (TAA) mice and were restored by cannabidiol (CBD).

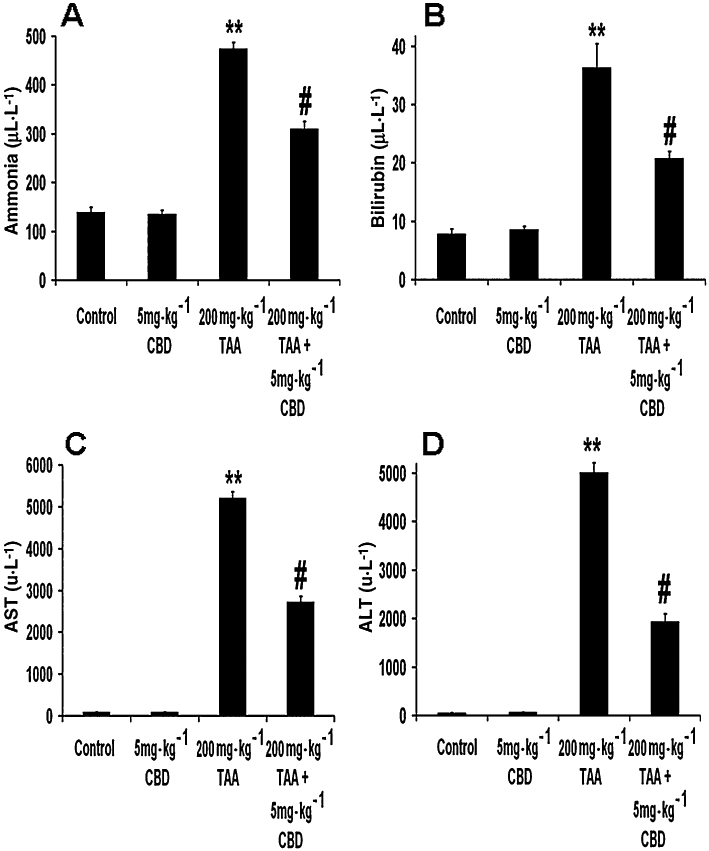

Liver function

The levels of ammonia (Figure 6A), bilirubin (Figure 6B) and the liver enzymes AST (Figure 6C) and ALT (Figure 6D) were increased after TAA administration (ammonia: anova: F3,26= 156.93, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01 vs. control; bilirubin: anova: F3,27= 34.99, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01 vs. control; AST: anova: F3,27= 590.84, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01 vs. control; ALT: anova: F3,27= 314.95, P < 0.0001; Bonferroni: P < 0.01 vs. control). CBD partially restored all of these indices in TAA-treated animals (P < 0.01 vs. TAA only for all parameters). CBD did not affect the levels of any of these substances in control animals.

Figure 6.

Indices of liver function. The levels of ammonia (A), bilirubin (B), aspartate transaminase (AST) (C) and alanine transaminase (ALT) (D) were all increased in the plasma of thioacetamide (TAA) mice and were all reversed by cannabidiol (CBD). **P < 0.01 versus control, #P < 0.01 versus TAA.

Discussion

TAA administration induces acute liver failure which leads to CNS changes related to those seen in HE (Zimmermann et al., 1989; Magen et al., 2008; Avraham et al., 2006; 2008a; 2009;). The hepatotoxicity of TAA is due to the generation of free radicals and oxidative stress (Zimmermann et al., 1989). However, it is not clear whether TAA affects the brain directly or the liver (Albrecht et al., 1996). In previous studies both a CB1 antagonist and a CB2 or TRPV1 agonist have been shown to ameliorate the brain and liver damage that occurs in liver disease and HE (Avraham et al., 2006; 2008a,b; 2009; Mallat and Lotersztajn, 2008). Also CBD, an agonist of the 5-HT1A receptor, was found to ameliorate brain damage in a chronic model of HE induced by bile duct ligation. Hence, we investigated the potential of CBD as a treatment for HE induced by FHF. Our results indicated that it has a neuroprotective role in HE induced by FHF; CBD was found to restore liver function, normalize 5-HT levels and improve the brain pathology in accordance with normalization of brain function. We also showed that CBD affects both central functions: neurological score, motor and cognitive functions, brain 5-HT levels as well as astrogliosis and peripheral functions: reduced liver enzymes, ammonia and bilirubin. Therefore, we conclude that it acts both centrally and peripherally. In addition, it has been shown that CBD can cross the blood – brain barrier and act centrally (for review see Pertwee, 2009). Therefore, its effect may result from a combination of its actions in the liver and the brain. However, to elucidate its mechanism of action future experiments are needed to determine the effects of central administration of CBD.

Previous work from our laboratory has demonstrated an impaired neurological and motor function 3 days, and impaired cognition 12 days after TAA injection to mice (Avraham et al., 2006; 2008a; 2009;). These results were reproduced in the present study (Figures 1–3). In a more recent study from our laboratory, cognitive and motor deficits were observed 21 days after bile duct ligation, a chronic model of liver disease (Magen et al., 2009). The different durations of the development of HE symptoms in the two models apparently result from their different characteristics – an acute versus a chronic model of HE. In the latter model, CBD was found to improve cognition and locomotor activity, in accordance with our present data (Magen et al., 2009). However, in sharp contrast to the findings reported here no evidence for astrogliosis was found in that study (data not reported); in our acute model induced by TAA we observed astrogliosis after 3 days (Figure 4C). Those mice with histopathological alterations displayed an increased neurological score and decreased activity level, and 5 mg·kg−1 CBD reversed both the increase in the number of GFAP(+) cells, an index of neuroinflammation (Figure 4E), and the neurological and locomotor impairments (Figures 1 and 2), suggesting a link between neuroinflammation and motor and neurological deficits. Similar results were reported by Jover et al. (2006) who demonstrated a decrease in motor activity in bile duct-ligated rats on a high-protein diet, in association with astrogliosis, and by Cauli et al. (2009), who reported that treatment with an anti-inflammatory restored the motor activity in HE. In the work of Jover et al. (2006), astrogliosis was found only in the bile duct-ligated rats on a high protein diet, but not in the bile duct-ligated rats on a regular diet, similar to our previous findings (Avraham et al., 2009) This suggests that TAA causes more severe damage to the brain than bile duct ligation, and that hyperammonaemia is required to worsen the damage in bile duct-ligated rats to an extent that is equivalent to that observed in TAA mice. The reason for this may be that in chronic liver disease induced by bile duct ligation, compensation mechanisms are activated, which moderate the brain damage, while in the acute model induced by TAA, no such mechanisms can come into action because of the severity of the liver insult and the short interval of time between the induction of liver damage and the histopathological examination.

Kerfoot et al. (2006) showed the infiltration of peripheral monocytes into the brain of bile duct-ligated mice 10 days after the ligation and suggested that this infiltration may cause the activation of inflammatory cells in the brain. Therefore, it is conceivable that such a mechanism was responsible for the astrogliosis observed in our study, since we found evidence of liver inflammation (data not shown). As evident from the histopathology results, CBD did not appear to affect the development of TAA-induced necrotic lesions in the liver of mice. However, the levels of liver transaminases in the serum of CBD-treated mice were significantly reduced compared to their untreated counterparts, indicating that this substance contributed to a partial restoration of liver function. Recent evidence elucidating the complicated mechanisms involved in the release of hepatocyte cytosolic enzymes such as ALT and AST in the blood may explain the discrepancy between histopathology and serum biochemistry data observed in the present study. Indeed, it is now generally accepted that the release of cytosolic enzymes during both the reversible and irreversible phases of hepatocyte injury and therefore their appearance in blood does not necessarily indicate cell death and also that enzyme release during reversible cell damage occurs with an apparent lack of histological evidence of necrosis (Solter, 2005). Following this reasoning, it could be hypothesized that although CBD did not reduce the levels of histologically detectable necrosis, it may have ameliorated the minute reversible hepatocyte damage that causes the so-called ‘leakage’ of cytoplasmic ALT and AST in blood. The interaction between hyperammonaemia and inflammation as a precipitating factor for HE has been discussed in two recent reviews (Shawcross and Jalan, 2005; Wright and Jalan, 2007). Further work is required to reveal the exact mechanism/s of the manner by which liver damage is related to dysfunction/damage in the brain, and studies using antagonists of the A2A adenosine receptors, which are potential targets of CBD that may mediate its anti-inflammatory effect (Carrier et al., 2006), need to be carried out in order to elucidate the receptors involved in this effect.

Astrogliosis has also been shown to be involved in learning and memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. In this study, astrogliosis was reduced by caloric restriction, which also reversed the cognitive deficits and increased the expression of neurogenesis in related genes (Wu et al., 2008). Further studies, such as expression analysis of such genes using DNA microarray and evaluation of neurogenesis using BrdU staining, needs to be performed in order to explore the mechanisms through which TAA-induced astrogliosis impairs cognition, and through which CBD acts to improve it.

Even though astrogliosis was found a week before cognitive function was observed, and it is not definite whether it was long-lasting, this mechanism seems, in our eyes, to account for the cognitive dysfunction, rather than the increase in 5-HT level (Figure 5). The latter mechanism does not seem to be related to the cognitive dysfunction, even though this increase in 5-HT was reversed by CBD (Figure 5), as 5-HT depletion, not increase, has been shown to cause memory deficits in the eight arm maze (Mazer et al., 1997). On the other hand, there is much evidence that ammonia induces astrocyte swelling which via a number of mechanisms leads to impaired astrocyte/neuronal communication and synaptic plasticity, thereby resulting in a disturbance of oscillatory networks. The latter accounts for the symptoms of HE (for review see Häussinger and Görg, 2010), among them presumably the cognitive dysfunction.

An increased level of 5-HT in the brain of rats after TAA administration was reported by Yurdaydin et al. (1990). In addition, there is indirect evidence that this increase is related to decreased motor activity, as the nonselective 5-HT receptor antagonist methysergide increased motor activity in TAA-injected rats, while the selective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist seganserin did not (Yurdaydin et al., 1996). Likewise, we found that the level of 5-HT was increased following TAA administration and this was restored after CBD treatment (Figure 5). In parallel, motor activity was decreased following TAA injection and increased after CBD treatment, indicating a link between the increase in 5-HT and decrease in motor activity. Hence, it seems that CBD reversed the increased 5-HT level in the brains of TAA mice and thus reversed the decrease in their motor activity. A possible mechanism can be activation of 5-HT1A receptors by CBD (Russo et al., 2005; receptor nomencalture follows Alexander et al., 2008), as these receptors have been reported to inhibit 5-HT synthesis (Invernizzi et al., 1991). We have shown that the effects of CBD in a chronic model of HE, bile duct ligation, are mediated via the 5-HT1A receptors (Magen et al., 2010), and in an earlier study with the same model we demonstrated that the effects of CBD can be also mediated via A2A adenosine receptors (Magen et al., 2009). Thus, the effects of CBD can be mediated by 5-HT1A or/and A2A adenosine receptors. We think that in the current study the effects of CBD were mediated by the 5-HT1A receptor since activation of the receptor by CBD caused depletion of 5-HT (Figure 5). In our previous studies we showed that cognition is multifactorial and not dependent only on 5-HT levels, and therefore there is no direct correlation between cognition and 5-HT levels.

The reversal of astrogliosis was probably related to reduced hepatic toxin formation. Indeed, there is much evidence that ammonia induces astrocyte swelling, which via a number of mechanisms leads to impaired astrocyte/neuronal communication and synaptic plasticity, thereby resulting in a disturbance of oscillatory networks. The latter accounts for the symptoms of HE (for review see Häussinger and Görg, 2010), among them presumably the cognitive dysfunction. Neurological and motor functions were improved 2 and 3 days, respectively, after induction of hepatic failure at the same time as a partial reversal of the astrogliosis and reduced levels of ammonia, bilirubin and liver enzymes were noticed. It seems that the behavioural effects of CBD are dramatic and occur within 3 days.

In summary, the present study demonstrates the therapeutic effects of CBD in an acute model of HE. It appears that this effect of CBD is multifactorial and involves cannabinoid (Avraham et al., 2006), vanilloid (Avraham et al., 2008a; 2009;) and 5-HT1A receptors (Magen et al., 2010). CBD improves the symptoms of FHF by affecting both brain histopathology and liver function, and thus may serve as therapeutic agent for treating human HE.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Israel Science Foundation for their support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- AUC

area under the curve

- CBD

cannabidiol

- FHF

fulminant hepatic failure

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- NS

normal saline

- TAA

thioacetamide

Conflict of interest

None.

Supplementary material

Supporting Information: Teaching Materials; Figs 1–6 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Albrecht J, Hilgier W, Januszewski S, Quack G. Contrasting effects of thioacetamide-induced liver damage on the brain uptake indices of ornithine, arginine and lysine: modulation by treatment with ornithine aspartate. Metab Brain Dis. 1996;11:229–237. doi: 10.1007/BF02237960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition (2008 revision) Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham Y, Israeli E, Gabbay E, Okun A, Zolotarev O, Silberman I, et al. Endocannabinoids affect neurological and cognitive function in thioacetamide-induced hepatic encephalopathy in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham Y, Zolotarev O, Grigoriadis NC, Poutahidis T, Magen I, Vorobiav L, et al. Cannabinoids and Capsaicin improve liver function following Thioacetamide – induced acute injury in mice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008a;103:3047–3056. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham Y, Magen I, Zolotarev O, Vorobiav L, Pappo O, Ilan Y, et al. 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor agonist, in various rat tissues during the eveloution of experimental cholestatic liver disease. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008b;79:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham Y, Grigoriadis N, Pautahidis T, Magen I, Vorobiav L, Zolotarev O, et al. Capsaicin affects brain function in a model of hepatic encephalopathy associated with fulminant hepatic failure in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:896–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shabat S, Hanuš LO, Katzavian G, Gallily R. New cannabidiol derivatives: synthesis, binding to cannabinoid receptor, and evaluation of their antiinflammatory activity. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1113–1117. doi: 10.1021/jm050709m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth RF. Altered glial-neuronal crosstalk: cornerstone in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Auchampach JA, Hillard CJ. Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter by cannabidiol: a mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7895–7900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511232103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli O, Rodrigo R, Piedrafita B, Llansola M, Mansouri MT, Felipo V, et al. Neuroinflammation contributes to hypokinesia in rats with hepatic encephalopathy: ibuprofen restores its motor activity. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1369–1374. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Constantini S, Trembovler V, Weinstock M, Shohami E. An experimental model of closed head injury in mice: pathophysiology, histopathology, and cognitive deficits. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13:557–568. doi: 10.1089/neu.1996.13.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durst R, Danenberg H, Gallily R, Mechoulam R, Meir K, Grad E, et al. Cannabidiol, a nonpsychoactive Cannabis constituent, protects against myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3602–H3607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00098.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy. In: Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, editors. Bockus Gastroenterology. 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 1998–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Martínez A, Callejas NA, Casado M, Boscá L, Martín-Sanz P. Thioacetamide-induced liver regeneration involves the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and nitric oxide synthase 2 in hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2004;40:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Mechoulam R. Pharmacological activity of the cannabinoid receptor agonist, anandamide, a brain constituent. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;231:313–314. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90468-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. The isolation and structure of delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other neutral cannabinoids from hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:217–224. doi: 10.1021/ja00730a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S, Avraham Y, Bonne O, Berry EM. Separation-induced body weight loss, impairment in alternation behavior, and autonomic tone: effects of tyrosine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häussinger D, Görg B. Interaction of oxidative stress, astrocyte swelling and cerebral ammonia toxicity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:87–92. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333b829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda H, Ikejima K, Hirose M, Yoshikawa M, Lang T, Enomoto N, et al. Leptin is required for fibrogenic responses induced by thioacetamide in the murine liver. Hepatology. 2002;36:12–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi R, Carli M, Di Clemente A, Samanin R. Administration of 8-hydroxy-2-(Di-n-propylamino)tetralin in raphe nuclei dorsalis and medianus reduces serotonin synthesis in the rat brain: differences in potency and regional sensitivity. J Neurochem. 1991;56:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo AA, Borrelli F, Capasso R, Di Marzo V, Mechoulam R. Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: new therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.006. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jover R, Rodrigo R, Felipo V, Insausti R, Sáez-Valero J, García-Ayllón MS, et al. Brain edema and inflammatory activation in bile duct ligated rats with diet-induced hyperammonemia: a model of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:1257–1266. doi: 10.1002/hep.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfoot SM, D’Mello C, Nguyen H, Ajuebor MN, Kubes P, Le T, et al. TNF-α secreting monocytes are recruited into the brain of cholestatic mice. Hepatology. 2006;43:154–162. doi: 10.1002/hep.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen SD, Bonne OB, Avraham Y, Berry EM. Separation as a new animal model for self-induced weight loss. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magen I, Avraham Y, Berry EM, Mechoulam R. Endocannabinoids in liver disease and hepatic encephalopathy. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2362–2369. doi: 10.2174/138161208785740063. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magen I, Avraham Y, Ackerman Z, Vorobiev L, Mechoulam R, Berry EM. Cannabidiol ameliorates cognitive and motor impairments in mice with bile duct ligation. J Hepatol. 2009;51:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magen I, Avraham Y, Ackerman Z, Vorobiav L, Mechoulam R, Berry EM. Cannabidiol ameliorates cognitive and motor impairments in bile-duct ligated mice via 5-HT1A receptor activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:950–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfait AM, Gallily R, Sumariwalla PF, Malik AS, Andreakos E, Mechoulam R, et al. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9561–9566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160105897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat A, Lotersztajn S. Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets in the management of liver diseases. Drug News Perspect. 2008;21:363–368. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2008.21.7.1255306. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazer C, Muneyyirci J, Taheny K, Raio N, Borella A, Whitaker-Azmitia P. Serotonin depletion during synaptogenesis leads to decreased synaptic density and learning deficits in the adult rat: a possible model of neuro developmental disorders with cognitive deficits. Brain Res. 1997;760:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Samuelson RJ. Remembrance of places passed: spatial memory in rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1976;2:97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Emerging strategies for exploiting cannabinoid receptor agonists as medicines. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick CG, Yanai J. Eight arm maze for mice. Int J Neurosci. 1983;21:63–66. doi: 10.3109/00207458308986121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggio O, Efrati C, Catalano C, Pediconi F, Mecarelli O, Accornero N, et al. High prevalence of spontaneous portal-systemic shunts in persistent hepatic encephalopathy: a case-control study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK. Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1A receptors. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-6978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnur J, Oláh J, Szepesi A, Nagy P, Thorgeirsson SS. Thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis in transforming growth factor beta-1 transgenic mice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:127–133. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawcross D, Jalan R. The pathophysiologic basis of hepatic encephalopathy: central role for ammonia and inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2295–2304. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5089-0. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, Jalan R. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solter PF. Clinical pathology approaches to hepatic injury. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33:9–16. doi: 10.1080/01926230590522086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl J. Studies of the blood ammonia in liver disease. Its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance. Ann Intern Med. 1963;58:1–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-58-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G, Jalan R. Ammonia and inflammation in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy: pandora's box? Hepatology. 2007;46:291–294. doi: 10.1002/hep.21843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Shen Q, Dong S, Xu Z, Tsien JZ, Hu Y. Calorie restriction ameliorates neurodegenerative phenotypes in forebrain-specific presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 double knockout mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1502–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurdaydin C, Hörtnagl H, Steindl P, Zimmermann C, Pifl C, Singer EA, et al. Increased serotonergic and noradrenergic activity in hepatic encephalopathy in rats with thioacetamide-induced acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1990;12:695–700. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurdaydin C, Herneth AM, Püspök A, Steindl P, Singer E, Ferenci P. Modulation of hepatic encephalopathy in rats with thioacetamide-induced acute liver failure by serotonin antagonists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:667–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann C, Ferenci P, Pifl C, Yurdaydin C, Ebner J, Lassmann H, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in thioacetamide-induced acute liver failure in rats: characterization of an improved model and study of amino acid-ergic neurotransmission. Hepatology. 1989;9:594–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.