Abstract

Background & Aims

Mutations in TP53, a tumor suppressor gene, are associated with prognosis of many cancers. However, the prognostic values of TP53 mutation sites are not known for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) because of heterogeneity in their geographic and etiological backgrounds.

Methods

TP53 mutations were investigated in a total of 409 HCC patients, including Chinese (n=336) and Caucasian (n=73) patients, using direct sequencing method.

Results

A total of 125 TP53 mutations were found in Chinese patients with HCC (37.2 %). HCC patients with TP53 mutations had a shorter overall survival time compared with patients with wild-type TP53 (hazard ratio [HR], 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.37–2.52; P<0.001). The hotspot mutations R249S and V157F were significantly associated with worse prognosis in univariate (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.51–2.94; P<0.001) and multivariate analyses (HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.29–2.51; P<0.001). Gene expression analysis revealed the existence of stem cell-like traits in tumors with TP53 mutations. These findings were validated in breast and lung tumor samples with TP53 mutations.

Conclusions

TP53 mutations, particularly the hotspot mutations R249S and V157F, are associated with poor prognosis for patients with HCC. The acquisition of stem cell-like gene expression traits might contribute to the aggressive behavior of tumors with TP53 mutation.

Keywords: Liver cancer, p53, gene expression patterns, cancer stem cells

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers with dismal clinical outcome accounting for the third highest cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Significantly, China alone accounts for more than 55 % of liver cancer in the world1, and the incidence of HCC continues to increase in the United States and Western Europe.2 In addition, the clinical heterogeneity of HCC and the lack of good diagnostic markers and treatment options have rendered this disease a major health problem.

TP53 is a multifunctional transcription factor that, along with number of other functions, regulates genes involved in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and senescence in response to various types of stress. Mutations of TP53 are frequently found in human cancers, and are generally associated with poor prognosis. In HCC, several studies have shown the association of TP53 mutations with poor survival.3–5 However, these studies were limited to specific populations with small sample size. In addition, overwhelming evidence demonstrated multi-factorial association of TP53 mutation spectra with environmental and etiological factors, resulting in variations among geographic regions, racial and ethnic groups.6, 7 In particular, the mutation at codon 249 position (R249S) is prevalent in China and sub-Saharan Africa.8 This site preference is known to associate with the dietary exposure to aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and HBV infection.9 Therefore, the prognostic value of TP53 mutations needs to be evaluated in the context of such confounding factors. Furthermore, TP53 mutations in different structural and functional regions of TP53 are associated with different prognostic values in diverse cancer types.10–12 However, the prognostic values of the different sites of TP53 mutations in HCC have not yet been rigorously evaluated.

In this study, we investigated the prognostic significance of the TP53 mutations in a Chinese cohort of HCC patients and evaluated the impact of individual mutations on prognosis. We found that hotspot mutations at codon 249 and 157 are significantly associated with patients’ survival. Additionally, we demonstrated that the TP53 mutated tumors express “stemness”-related genes suggesting a potential progenitor cell origin. These results have both biological and clinical implications for TP53 mutated HCC.

Materials and Methods

Direct sequencing of TP53

A total of 409 HCC patients including 336 Chinese patients collected from Qidong (n=120) and Shanghai (n= 216) areas and 73 Caucasian patients from Belgium (n=47) and United States (n=26) were analyzed. Direct sequencing of TP53 exon 5 through 8 was performed using cDNAs obtained from frozen tissue specimens by reverse transcription PCR. Genomic DNAs were used in case of the cDNA samples were not available. Sequencing reaction was performed using ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer with BigDye terminator sequencing reaction kit (Version 1.1). The primers for sequencing reaction and PCR are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Compiling Gene Expression Data Sets

Gene expression data sets from the LEC (data from the Laboratory of Experimental Carcinogenesis, GSE1898 and GSE4024), GSE5975 13, and a publicly available data E-TABM-3614 were complied together. For each data set, average expression levels of each array and gene were set to 0, and each array was scaled to have standard deviation 1. For multiple tagged gene features for the same Entrez Gene identifier, the gene feature with the highest magnitude (i.e. sum of square of each sample) was used as a representative gene feature. Non-tumor samples or the samples without TP53 mutations were excluded and finally 366 HCC profiles were compiled. For external validation, a breast cancer data (GSE3494, n=251)15 with two platforms of Affymetrix (HGU-133A and HGU-133B) and a compiled lung cancer data set of GSE11969 (n=149)16 and GSE8569 (n=69) were used. Preprocessing of each data set was performed by the same method as described above.

Enrichment of Gene Expression Signatures

The enrichment of gene sets in individual tumors was determined as described previously.17 Briefly, for each array, we assessed the fraction of up- or down-regulated genes with a fold difference greater than 2 in each tested gene set. The gene set enrichment was calculated by hypergeometric test with a threshold of P < 0.01 for significant enrichment. The enrichment scores Sup and Sdown for a given signature were calculated as −log10 (P-value) from up- and down-regulated gene sets, respectively. The enrichment score S was defined as Sup if Sup > Sdown and Sdown if Sup < Sdown. The enrichment patterns across groups were determined by calculating fraction of the significantly enriched samples in a group, and the significance of the group enrichment was calculated by hypergeometric test.

Embryonic stem (ES) cell-related signatures (i.e. ES1, ES2, NOS, NOS_TF, and the target genes for Nanog, Oct4, Sox2, Myc1, and Myc2) and proliferation-related gene signature (prol) were obtained from the previous publication site.17 NOS includes the target genes for Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2. NOS_TF includes a subset of NOS activation targets encoding transcription regulators. We also obtained rat hepatoblast (HB) gene signatures (n=191) which contained over-expressed (HB_UP) and down-regulated (HB_DOWN) genes in early fetal liver development.18 For the validation using breast and lung cancer data, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA, version 2.0) was applied with default parameters.19

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

The same amount of first-strand cDNA from each sample was used to detect the mRNA expression levels using specific primers (CD24 sense 5'-ACAGCCAGTCTCTTCGTGGT-3', anti-sense 5'-CCTGTTTTTCCTTGCCACAT-3'; AFP sense 5'-AGCTTGGTGGTGGATGAAAC-3', anti-sense 5'-CCCTCTTCAGCAAAGCAGAC-3'; GAPDH sense 5'-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3', anti-sense 5'-TTCTAGACGGCAGGTCAGGT-3'). PCR was carried out with a SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA) of 40 cycles for 10 min at 95 °C, 15 sec at 95 °C, 30 sec at 60 °C, with a final dissociation step of 15 sec at 95 °C, 20 sec at 60 °C, 15 sec at 95 °C using ABI 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each sample was assayed in duplicate and a control normal liver DNA was included in every assay. The mRNA expression levels were normalized with that of the GAPDH, and the relative values compared to a normal liver sample were calculated (−ΔΔCT).

Statistical Analysis

Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan-Meir method and log-rank test. The association of clinical features with TP53 mutations was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate analysis for survival data were performed by using Cox proportional hazard models. qPCR result was analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Profiling of TP53 Mutation Status in HCC

A total of 134 mutations were found in 409 HCC patients (Supplementary Table 2). Of these, 1 case of silent mutation, 2 cases of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (R213R), and 1 case of a deletion at splicing site were excluded from the analysis. For tumors with more than one mutation, the mutations were counted as a single event. In Chinese cohort (n=334), 125 cases of TP53 mutations (37.4 %) including miss-sense (120 cases), 4 non-sense, and 1 frame shift mutations were found. The patients from Qidong showed higher mutation rate compared with the patients from Shanghai areas (54.1 % and 28.0 %, respectively). In accordance with the previous studies 6, 20, codon 249 of TP53 (R249S) was the most common mutation (24.4 %, 77 cases) both in the samples from Qidong (36.6 %, 44 cases) and Shanghai (14.4 %, 31 cases). Codon 157 (V157F) was the second most common mutation site (2.4 %, 8 case), particularly in Qidong province (7 cases). By contrast, Caucasian HCC patients showed low mutation rate (7.0 %, 5 out of 71) with mutations at codon 249 (3 cases) and codon 157 (2 cases).

Clinico-Pathological Features Related to TP53 Mutation Status

Due to the very high heterogeneity between the mutation status of Chinese and Caucasian people which could introduce bias, survival analysis was confined to the Chinese cohort. The survival data were available in a total of 329 out of the 334 Chinese patients. Follow-up time was truncated to five years after surgical resection. Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to characterize the prognostic association of clinico-pathological features. Of the clinical features, serum AFP (> 300 ng/ml), tumor size (>5 cm), and tumor grade (> III, IV) were significantly associated with the increased risk of death (P<0.001, Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis for selected clinical features of HCC

| Number of patients |

Hazard Ratio |

95% CI lower |

95% CI upper |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 282/48 | 1.23 | 0.78 | 1.93 | 0.369 |

| Age (<50/≥50, year) | 173/157 | 1.30 | 0.95 | 1.76 | 0.097 |

| AFP (≥300/<300 ng/ml) | 170/152 | 2.13 | 1.54 | 2.95 | <0.001 |

| Size (≥5/<5 cm) | 177/152 | 1.94 | 1.41 | 2.66 | <0.001 |

| Presence of cirrhosis (yes/no) | 249/80 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 1.11 | 0.182 |

| Grade (III,IV/I,II) | 184/108 | 1.82 | 1.28 | 2.58 | <0.001 |

| HBV (+/−) | 296/38 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.93 | 0.022 |

| HCV (+/−) | 5/329 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 2.48 | 0.269 |

| TP53 mutation types | |||||

| Any types | 125/209 | 1.86 | 1.37 | 2.53 | <0.001 |

| R249S | 77/209* | 1.98 | 1.41 | 2.80 | <0.001 |

| V157F | 8/209* | 4.25 | 1.95 | 9.27 | <0.001 |

| Hotspot mutations | 84/209 | 2.11 | 1.51 | 2.94 | <0.001 |

| Non-hotspot mutations | 41/209 | 1.44 | 0.89 | 2.31 | 0.134 |

One case of double mutation with R249S and V157F was counted as a separate event.

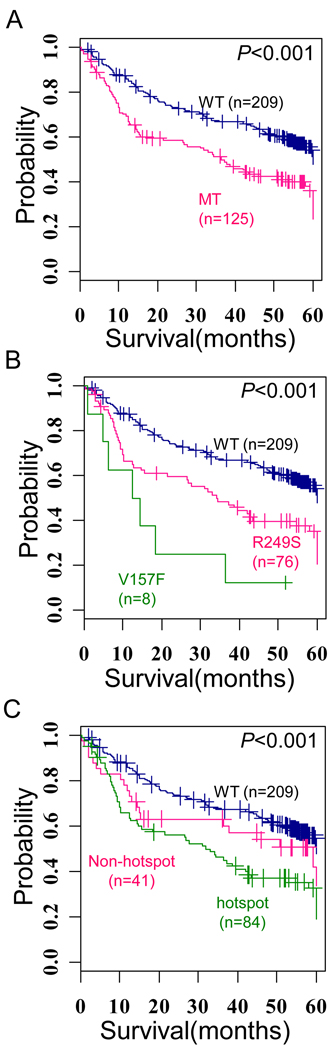

Kaplan-Meir plot analysis showed the presence of TP53 mutations is significantly associated with shorter overall survival (Hazard ratio [HR], 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.37–2.52; P<0.001) (Figure 1A). Interestingly, when we examined the prognostic values of individual mutations, we found that highly frequent mutations i.e. hotspot mutations (mutation rate > 2%) at codon 249 and codon 157 are significantly associated with worse survival (HR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.41–2.80; P=7.1×10−5, HR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.97–9.27; P<0.001, respectively) (Figure 1B). Grouping the patients with hotspot mutations (84/125, 67.2% cases with mutations) also showed shorter survival than patients with the wild-type TP53 (P<0.001) (Figure 1C). Multivariate analysis including TP53 mutations also revealed that only the hotspot mutations are independent risk factors for overall survival (Hazard ratio, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.29–2.51; P<0.001, Table 2). These results suggest that the hotspot mutations mainly contribute to the heterogeneous progression of HCC.

Figure 1. Prognostic values of TP53 mutation sites.

(A) Kaplan-Meir plot for survival between the tumors of mutation-type (MT) and wild-type (WT) TP53. (B). Kaplan-Meir plot for survival between the tumors with R249S and V157F mutations. (C) Kaplan-Meir plot for survival between the tumors with hotspot (i.e. R249S and V157F) and non-hotspot mutations. The + symbols in panel indicate censored data.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis for the selected clinical features of HCC

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation any types | ||||

| Sex (male/female) | 1.09 | 0.67 | 1.79 | 0.730 |

| Age (<50/≥50, year) | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.27 | 0.580 |

| AFP (≥300/<300 ng/ml) | 1.76 | 1.24 | 2.50 | 0.002 |

| Size (≥5/<5 cm) | 1.68 | 1.19 | 2.38 | 0.004 |

| Presence of cirrhosis (yes/no) | 0.99 | 0.68 | 1.43 | 0.950 |

| Grade (III,IV/I,II) | 1.73 | 1.21 | 2.48 | 0.003 |

| TP53 mutation any types | 1.79 | 1.29 | 2.51 | <0.001 |

| Mutation category | ||||

| Sex (male/female) | 1.07 | 0.65 | 1.75 | 0.800 |

| Age (<50/≥50, year) | 0.89 | 0.64 | 1.25 | 0.510 |

| AFP (≥300/<300 ng/ml) | 1.77 | 1.24 | 2.52 | 0.002 |

| Size (≥5/<5 cm) | 1.71 | 1.21 | 2.43 | 0.003 |

| Presence of cirrhosis (yes/no) | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.50 | 0.880 |

| Grade (III,IV/I,II) | 1.70 | 1.19 | 2.44 | 0.004 |

| Hotspot mutations | 1.97 | 1.36 | 2.86 | <0.001 |

| Non-hotspot mutations | 1.47 | 0.88 | 2.44 | 0.140 |

Previously, classification of TP53 mutations based on the structural properties revealed distinct prognostic values in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck.10, 11 We therefore evaluated whether the structural classifications of TP53 mutations have different prognostic values in HCC. The TP53 mutations were categorized based on the structural properties as described in the TP53 mutation database of International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC, http://www-p53.iarc.fr). The HCC patients with mutations at the DNA binding motifs (loop-L3) and S4 beta-sandwich regions showed a significantly shorter survival compared with the wild-type TP53 patients (Supplementary Table 3). These results seem to be largely due to the profound prognostic values of the two hotspot mutations at codon 249 and 157 which are located in L3 and S4, respectively. However, mutations located outside the L3 or S4 were also associated with a poor prognosis albeit with a marginal significance (P=0.053 and P=0.048, respectively), indicating that these structural properties may not be proficient in classifying the prognostic outcome. We also applied another classification of disruptive vs. non-disruptive mutations based on the mutation location and the predicted amino acid alterations.11 Differing from the previous analysis, both disruptive and non-disruptive mutations were associated with a worse prognosis (P<0.001 and P=0.048, respectively, Supplementary Table 3), which might be due to the non-disruptive nature of V157F mutation. These findings suggest that the hotspot mutation frequency rather than structural or functional classifications of TP53 mutations is a more significant prognostic indicator at least in the Chinese cohort.

The association of TP53 mutations with clinical features was also investigated (Supplementary Table 4). TP53 mutations were more frequent in the patients with high serum AFP level (> 300 ng/ml) and patients without cirrhosis (P<0.05). Hotspot mutations were more frequent in young patients (P=0.019) and patients without cirrhosis (P=0.007). The association of TP53 mutation with HBV infection has been reported previously 6, 21, however, we could not assess this finding because most of the patients in our cohort were HBV infected.

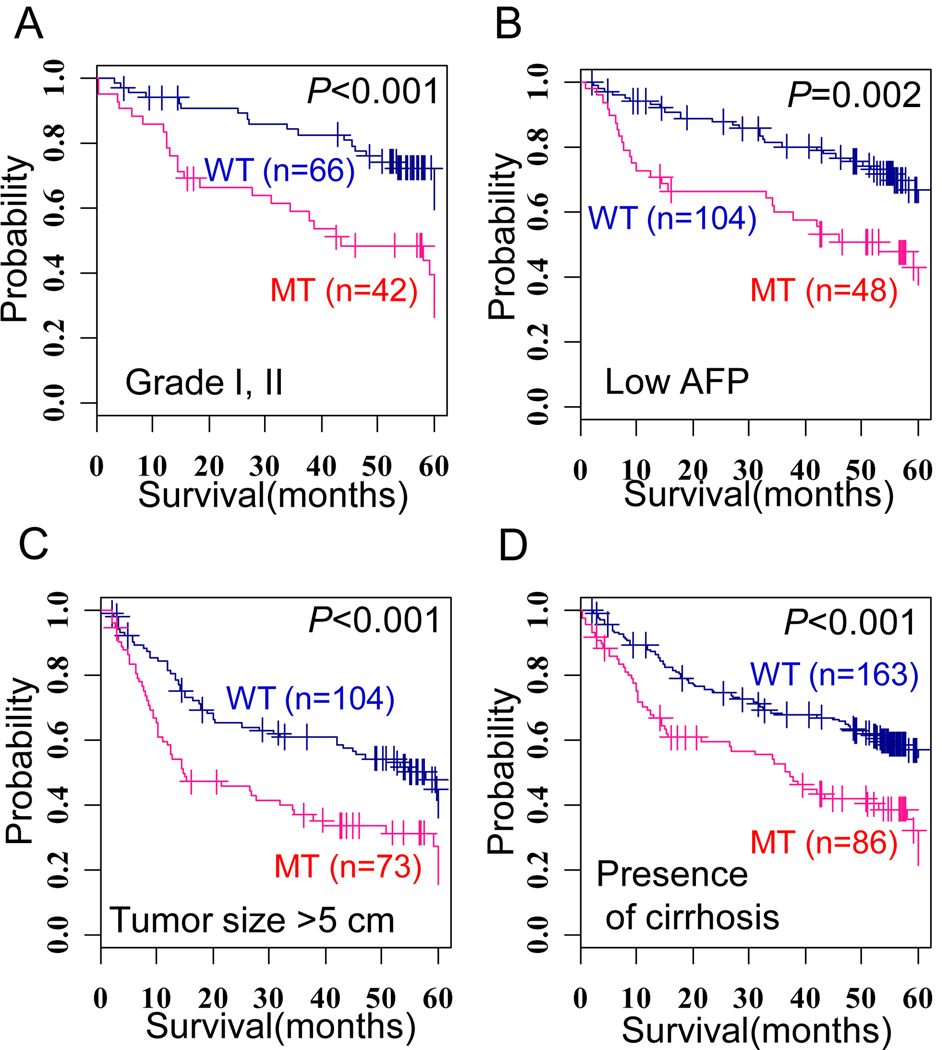

Next, we tested whether a combination of clinico-pathological features and TP53 mutations could improve the stratification of the prognostic subgroups. Patients with TP53 mutations could be stratified according to a poor survival in each of the subpopulations with a low tumor grade (I, II), low serum AFP level (< 300 ng/ml), large tumor size (>5 cm), or presence of liver cirrhosis (Figure 2). The patients with hotspot TP53 mutations showed similar prognostic values in these subpopulations (Supplementary Figure 1). These results suggest that a combined application of TP53 mutation status with the conventional clinical features would be a practical approach to predict the patient’s survival.

Figure 2. Prognostic value of combined status of TP53 mutation and other clinical features.

(A–D) Kaplan-Meir plots for survival between patients with mutation-type (MT) and wild-type (WT) TP53 in subpopulations of patients who have a low tumor grade (I, II) (A), low serum AFP level (< 300 ng/ml) (B), large tumor size (> 5cm), (C), or liver cirrhosis (D). The + symbols in panel indicate censored data.

Gene Expression Profiles Reflect the Prognostic Value of TP53 Mutation Sites

Gene expression profile analysis was performed to further characterize the tumors according to the TP53 mutation status. A total of 366 HCC gene expression profiles having TP53 mutation status were compiled together (see Materials and Methods). It includes 238 Chinese samples with 89 cases of TP53 mutation and 128 Caucasian samples with 19 cases of TP53 mutation. We performed an unbiased estimation of the functional gene set enrichments using Gene Ontology (GO) hierarchy. Considering the complexity of the TP53 biology and molecular heterogeneity of each sample, gene set enrichment analyses were performed on the individual HCC samples not the groups (see Materials and Methods for details). The unbiased screening of the gene set enrichment revealed a profound increase in proliferation-related gene expression activity in the TP53 mutated tumors with the enrichment of transcription/cell cycle-related functions (Supplementary Figure 2A). By contrast, the wild-type tumors were enriched with the metabolism-related genes, which may indicate a conservation of liver functions. The same patterns were observed in both Chinese (n=238) and Caucasian (n=128) cohorts. The comparison of hotspot and non-hotspot mutations was performed using Chinese cohort because of the marked difference in the mutation frequency in Caucasian cohort. Consistent with the different prognostic values, the proliferation-related genes were prevalently enriched in the hotspot-mutated tumors compared with the non-hotspot mutated tumors (Supplementary Figure 2B). These data indicate that the distinct prognostic significance of TP53 mutations, particularly the hotspot mutations, is a consequence of the molecular alterations rather than by-chance casual association with the clinical data.

TP53 Mutations are Associated with Stem Cell-Like Gene Expression Traits

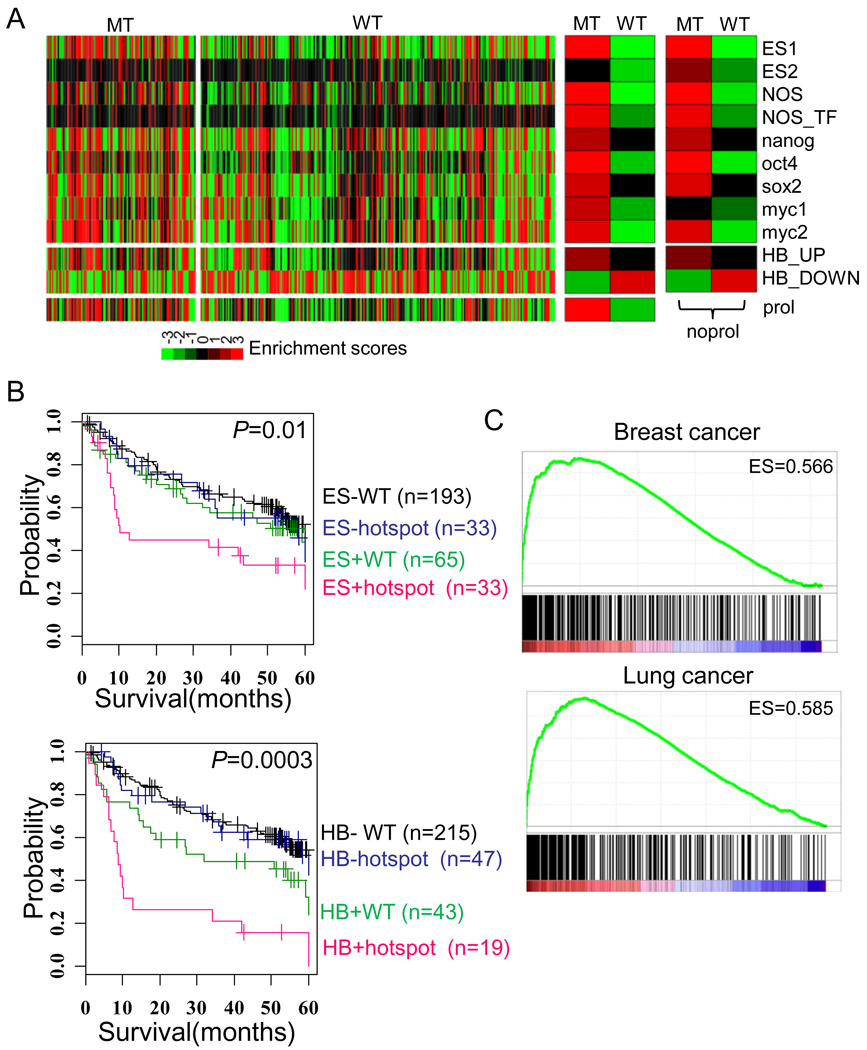

It has been suggested that the tumors originated from the stem/progenitor cells acquire a more aggressive phenotype in numerous cancer types.17, 22 Moreover, several recent studies have shown association between TP53 mutations and the “stemness” of cancer cells (see also Discussion). To address this issue in human tumor specimens, we measured the expression of stemness genes by the enrichment scores of multiple stem cell-related genes rather than the expression of individual stem cell marker genes as described in previous study.17 It has been suggested that detection of the activity of such stemness-related complex networks rather than the expression of individual genes is more important, because different ES regulators may activate stem-cell regulatory networks in each tumors. Enrichment of various embryonic stem (ES) and hepatoblast (HB)-related gene signatures (for details see Materials and Methods) was calculated in individual tumors of the HCC data set (n=366). We found that the ES-related and HB signatures were concomitantly enriched in the TP53 mutated tumors but repressed in the wild-type tumors (Figure 3A). To exclude the contribution of the proliferation related-genes in the stem cell signature, we tested the enrichment of the signatures after subtracting the proliferation-related genes as described previously.17 The results were similar suggesting that the enrichment of the stem cell-related signatures in the TP53 mutated tumors was independent of the expression of proliferation-related genes (Figure 3A, right). In addition, when the tumors were classified according to the status of stem cell-like expression (i.e., HB and ES) and hotspot TP53 mutation, they showed correlation with patient’s survival supporting the prognostic significance of TP53 mutation and stem cell traits (Figure 3B). Classification with mutations with any types (MT vs. WT) also demonstrated a similar result (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 3. Expression of stem cell-like traits in TP53 mutated tumors.

(A) The enrichment scores for the ES signatures and HB signatures in the compiled HCC data set are shown on the left; the enrichment in groups of mutation-type (MT) and wild-type (WT) is shown in the middle; and the enrichments of ES signature without the proliferation-related genes (noprol) are shown on the right. The enrichment scores in each sample and group represent −log10 (P-value) calculated by hypergeometric test. (B) Based on the expression status of ES1 (upper) or HB (lower) signatures and the hotspot TP53 mutation status, the 366 patients were stratified into four groups. 42 cases of non-hotspot mutations were not included in the analysis. ES+ represent the tumors which were enriched with ES1 signature (P<0.01), while other tumors were indicated as ES−. HB+ represents the tumors which were positively enriched with HB_UP and negatively enriched with HB_DOWN signatures (P<0.01), while other tumors were indicated as HB−. (C) The plots showed the enrichment scores (ES) for the ES1 signature in breast cancers (upper) and lung cancers (lower) were calculated by GSEA method.

The generality of our finding was evaluated by extending our analysis to the public data sets of breast cancer (n=251) and lung cancer (n=218) using GSEA method.19 Similar to HCC, there was a significant up-regulation of ES trait in the TP53 mutated tumors compared with wild-type breast and lung cancers (Figure 3B,C and Supplementary Table 5). These findings suggest that the stem cell-like traits are a common feature of tumors harboring TP53 mutations.

Validation of Stem Cell-Like Gene Expression in TP53 mutated tumors

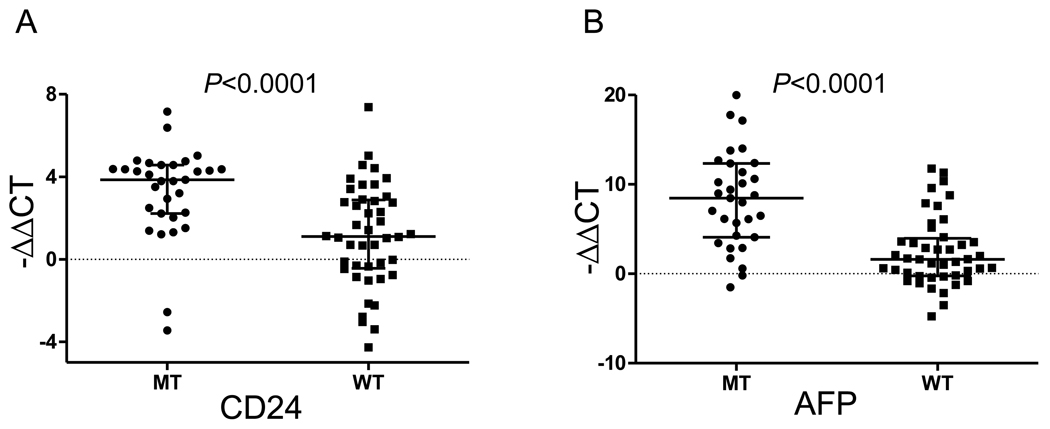

Next, we evaluated the expression of stemness-related genes, and identified fourteen differentially overexpressed genes in mutated tumors compared to wild-type tumors by performing 10,000 permuted two-sample T-test (P<0.01) with greater than two fold difference (Supplementary Table 6). Notably, CD24 highly expressed in TP53 mutated as compared with wild type tumors. CD24 has been proposed as a stemness marker in numerous types of cancers including ovary23, pancreas24, and colon cancers.25 In addition, AFP was found in the gene list, which is recognaized as a cancer stem cell marker in combination with EpCam in HCC.26 To confirm our finding, the expression levels of CD24 and AFP were measured by quantitative RT-PCR on 75 samples of mutant type (MT, n=31) and wild-type (WT, n=44) HCC. Significant overexpression of CD24 and AFP was found in the mutant as compared to the wild-type tumors (Mann-Whitney U test, P<0.0001, Figure 4A, B). Taken together, our results support the association of TP53 mutations with the enriched expression of stemness-related traits.

Figure 4. Validation of CD24 and AFP expression by quantitative PCR.

(A, B) Expression of CD24 (A) and AFP (B) levels in mutant type (MT, n=31) and wild-type (WT, n=44) HCCs were measured by quantitative PCR. Statistical significance was tested by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. Median and interquartile ranges were indicated by horizontal lines.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that the TP53 mutations in Chinese HCC are associated with poor clinical outcome. In particular, the hotspot mutations, i.e. R249S and V157F, are strongly associated with bad prognosis. Evaluation of site specific prognostic values of mutations may be helpful in delineating mutant p53 functions as well as its clinical implication.

The reason(s) for the worse prognostic feature associated with the hotspot mutations of TP53 is unclear. It has been suggested that the hotspot mutations, arising from the clonal expansion of the mutated cells during cancer progression, can provide a selective advantage for tumor cell survival 27 and/or that they are more deleterious than the non-hotspot mutations.28 Indeed, accumulating evidence supports the functional alterations of the hotspot mutations, i.e. R249S and V157F.29–31 It is also possible that the different mode-of-actions can contribute to their prognostic distinction., R249S is frequently found, both in normal and cirrhotic liver. in high AFB1 exposure area, suggesting that R249S mutation occurs at the early stage of hepatocarcinogenesis, while other mutations seem to be more prevalent at later stages.32, 33 Similarly in lung cancer, V157F is frequently found in close association with cigarette smoking.27 These hotspot-specific features caused by the environmental exposure of mutagens result in G to T transversion and may be involved in the development of more aggressive phenotypes. However, considering the complexity of p53 biology, further studies are needed to delineate the mechanisms by which the hotspot mutations result in a worse prognosis.

We arbitrarily classified the tumors into hotspot vs. non-hotspot mutated tumors with mutation frequency of 2%. However, the prognostic values of the hotspot TP53 mutations are well reflected in their corresponding gene expression profiles. These data support the notion that the worse prognostic value of the hotspot mutations is not likely to be a biased observation due to the large number of cases or arbitrary classification. In addition, we found that the TP53 mutations are accompanied by the expression of stem cell like-traits. Although further validation was not performed here for the causal link between TP53 mutations and stem cell-traits, it was already known that the p53 is involved in the stem cells self-renewal by suppressing NANOG expression.34 It has also been shown that neural stem cells harboring TP53 mutations have increased potential to accumulate genetic lesions and generate glioblastomatosis.35 Moreover, it was recently shown that TP53 is critical for reprogramming of differentiated cells into pluripotent stem cells.36 Similarly, our data support the view that the acquisition of stem cell-like traits in the TP53 mutated tumors play important role in the generation and/or progression of poor prognostic phenotype. Accordingly, the invalidation of stem-stem traits might be novel potential therapeutic strategy especially for the TP53 mutated tumors.

In the present study, we observed the differential expression of the well-known putative CSC markers i.e. CD24 and AFP in TP53 mutated tumors compared to wild-type tumors, however, other putative liver CSC markers were not differentially expressed37–39. This might be due to the population heterogeneity of the stem-like tumors as well as TP53 mutated tumors activating different ES cell regulators. However, our data collectively suggest that the acquisition of stem-like trait in TP53 mutated tumors is a likely explanation for the aggressive phenotype of TP53 mutated tumors.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the TP53 mutations, particularly hotspot mutations, represent an independent risk factor for a shorter survival of the HCC patients. The acquisition of stem cell-like phenotype likely contributes to the aggressive behavior of TP53 mutated tumors. Our results may therefore have prognostic and therapeutic implications for the future management of HCC patients with TP53 mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the research grant of the Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea (3-2010027-0, 2010).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimers: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Authors involvement: Study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision and writing of the manuscript: Snorri S.Thorgeirsson and Huyn Goo Woo; Technical support : Yun Hee Kim and So Mee Kwon; Acquisition of data and critical revision of manuscript: Xin Wei Wang, Anuradha Budhu, Zhao-You Tang, Zongtang Sun, and Curtis C. Harris.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi H, Sugio K, Matsumata T, Adachi E, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. The clinical significance of p53 gene mutation in hepatocellular carcinomas from Japan. Hepatology. 1995;22:1702–1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda K, Sbisa E, Tullo A, Papeo PA, Saccone C, Poole S, Pignatelli M, Mitry RR, Ding S, Isla A, Davies A, Habib NA. p53 mutation is a poor prognostic indicator for survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing surgical tumour ablation. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:776–782. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yano M, Hamatani K, Eguchi H, Hirai Y, MacPhee DG, Sugino K, Dohi K, Itamoto T, Asahara T. Prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma correlates to mutations of p53 and/or hMSH2 genes. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain SP, Schwank J, Staib F, Wang XW, Harris CC. TP53 mutations and hepatocellular carcinoma: insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of liver cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2166–2176. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soussi T, Wiman K. Shaping genetic alterations in human cancer: the p53 mutation paradigm. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu IC, Metcalf RA, Sun T, Welsh JA, Wang NJ, Harris CC. Mutational hotspot in the p53 gene in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nature. 1991;350:427–428. doi: 10.1038/350427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozturk M. p53 mutation in hepatocellular carcinoma after aflatoxin exposure. Lancet. 1991;338:1356–1359. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92236-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young KH, Leroy K, Moller MB, Colleoni GW, Sanchez-Beato M, Kerbauy FR, Haioun C, Eickhoff JC, Young AH, Gaulard P, Piris MA, Oberley TD, Rehrauer WM, Kahl BS, Malter JS, Campo E, Delabie J, Gascoyne RD, Rosenwald A, Rimsza L, Huang J, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, Wilson WH, Staudt LM, Vose JM, Chan WC, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC. Structural profiles of TP53 gene mutations predict clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an international collaborative study. Blood. 2008;112:3088–3098. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-129783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poeta ML, Manola J, Goldwasser MA, Forastiere A, Benoit N, Califano JA, Ridge JA, Goodwin J, Kenady D, Saunders J, Westra W, Sidransky D, Koch WM. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2552–2561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:701–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia HL, Ye QH, Qin LX, Budhu A, Forgues M, Chen Y, Liu YK, Sun HC, Wang L, Lu HZ, Shen F, Tang ZY, Wang XW. Gene expression profiling reveals potential biomarkers of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1133–1139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reynies A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, Herault A, Saric J, Belghiti J, Franco D, Bioulac-Sage P, Laurent-Puig P, Zucman-Rossi J. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, Vega VB, Vergara L, Ploner A, Pawitan Y, Hall P, Klaar S, Liu ET, Bergh J. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13550–13555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi T, Tomida S, Yatabe Y, Kosaka T, Osada H, Yanagisawa K, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T. Expression profile-defined classification of lung adenocarcinoma shows close relationship with underlying major genetic changes and clinicopathologic behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1679–1688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petkov PM, Zavadil J, Goetz D, Chu T, Carver R, Rogler CE, Bottinger EP, Shafritz DA, Dabeva MD. Gene expression pattern in hepatic stem/progenitor cells during rat fetal development using complementary DNA microarrays. Hepatology. 2004;39:617–627. doi: 10.1002/hep.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda T, Tsuda H, Scarpa A, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. p53 gene mutation spectrum in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1992;52:6358–6364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirk GD, Lesi OA, Mendy M, Szymanska K, Whittle H, Goedert JJ, Hainaut P, Montesano R. 249(ser) TP53 mutation in plasma DNA, hepatitis B viral infection, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:5858–5867. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, Chu IS, Kaposi-Novak P, Calvisi DF, Mikaelyan A, Roberts LR, Demetris AJ, Sun Z, Nevens F, Roskams T, Thorgeirsson SS. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao MQ, Choi YP, Kang S, Youn JH, Cho NH. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:2672–2680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P, Burant CF, Zhang L, Adsay V, Wicha M, Clarke MF, Simeone DM. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1030–1037. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeung TM, Gandhi SC, Wilding JL, Muschel R, Bodmer WF. Cancer stem cells from colorectal cancer-derived cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3722–3727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915135107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, Kim JW, Ye Q, Jia H, Budhu A, Zanetti KA, Chen Y, Qin LX, Tang ZY, Wang XW. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1451–1461. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidransky D, Mikkelsen T, Schwechheimer K, Rosenblum ML, Cavanee W, Vogelstein B. Clonal expansion of p53 mutant cells is associated with brain tumour progression. Nature. 1992;355:846–847. doi: 10.1038/355846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, Olivier M. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:622–629. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuarai S, Yamanaka K, Kotani H. Mutant p53 induces the GEF-H1 oncogene, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor-H1 for RhoA, resulting in accelerated cell proliferation in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6319–6326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumenco L, Oguey D, Wu J, Messier N, Fausto N. Introduction of a murine p53 mutation corresponding to human codon 249 into a murine hepatocyte cell line results in growth advantage, but not in transformation. Hepatology. 1995;22:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90640-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghebranious N, Sell S. The mouse equivalent of the human p53ser249 mutation p53ser246 enhances aflatoxin hepatocarcinogenesis in hepatitis B surface antigen transgenic and p53 heterozygous null mice. Hepatology. 1998;27:967–973. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguilar F, Harris CC, Sun T, Hollstein M, Cerutti P. Geographic variation of p53 mutational profile in nonmalignant human liver. Science. 1994;264:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.8191284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teramoto T, Satonaka K, Kitazawa S, Fujimori T, Hayashi K, Maeda S. p53 gene abnormalities are closely related to hepatoviral infections and occur at a late stage of hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin T, Chao C, Saito S, Mazur SJ, Murphy ME, Appella E, Xu Y. p53 induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing Nanog expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:165–171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Yang J, Zheng H, Tomasek GJ, Zhang P, McKeever PE, Lee EY, Zhu Y. Expression of mutant p53 proteins implicates a lineage relationship between neural stem cells and malignant astrocytic glioma in a murine model. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460:1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, Zheng BJ, Guan XY. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Lau CK, Yu WC, Ngai P, Chu PW, Lam CT, Poon RT, Fan ST. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klonisch T, Wiechec E, Hombach-Klonisch S, Ande SR, Wesselborg S, Schulze-Osthoff K, Los M. Cancer stem cell markers in common cancers - therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.