Abstract

Objetive

To evaluate whether the use of oxytocin during first and second stages of labor is associated with higher incidence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in pregnant women who received active management of third stage of labor (AMTSL).

Study design

A secondary data analysis from vaginal deliveries in a hospital-based cohort study from 24 maternities in South America. The primary outcomes analyzed were: moderate PPH (≥500ml of blood loss), severe PPH (≥1000ml of blood loss) and need of blood transfusion.

Results

A total of 11,323 vaginal deliveries were included. The incidence of moderate and severe PPH was 10.8% and 1.86%, respectively. Overall, 36% received AMTSL. There was no association between induced/augmented labor and moderate PPH (p=0.753), severe PPH (p=0.273) and blood transfusion (p=0.603) in the population that received AMTSL.

Conclusion

AMTSL should be recommended regardless of whether pregnant women received or not oxytocin during the first and second stages of labor.

Keywords: Active management labor, augmentation, induction, oxytocin

Introduction

Third stage of labor is defined as the period of time between the delivery of the baby and the delivery of the placenta. The length of this stage and its subsequent complications depend on a combination of the length of time it takes for placental separation and the ability of the uterine muscle to contract (1). There is strong evidence that the active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL) reduces the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) by more than 40% (2;3). Currently, prestigious organizations such as the Joint Statement of the International Confederation of Midwifes (ICM), the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the World Health Organization recommend this practice for all vaginal deliveries as a way to prevent PPH in developed and developing countries (4–7).

AMTSL involves the administration of an oxytocic agent, early umbilical cord clamping and division and controlled cord traction for delivery of the umbilical cord (2). Oxytocin is the current drug of choice for AMTSL(8). As the binding of oxytocin to receptors on the myometrial cell membranes releases intracellular calcium and produces the uterine contractility, this drug is used as a potent stimulant of labor during early stages of labor (9). Oxytocin has been prescribed to induce labor from the beginning (induction of labor), or after the labor has been initiated and requires an oxytocic agent to improve uterine contractility (augmentation of labor)(10). Therefore, due to current recommendations many pregnant women who receive oxytocin during the third stage of labor are also exposed to receive the drug during the early stages of labor.

However, it has been observed that the use of oxytocin in first and second stages associated with AMTSL may be associated with an increase in blood loss and blood transfusion (11). This finding may be product of an interaction between the use of oxytocin during two different stages of labor, resulting in a decrease in the effect of active management of the third stage of labor on PPH. Robinson et al. showed that pre-treatment with oxytocin resulted in a decrease in the percentage of cells that responded to subsequent oxytocin exposure. The authors found that this oxytocin-induced desensitization occurred over a clinical time frame of 4.2 hours (12). Nevertheless, this potential interaction between oxytocin used during first and second stages and third stage of labor has not consistently been described (13).

The main objective of this current study is to evaluate whether the use of oxytocin during the first and second stages of labor is associated with a higher risk of PPH in pregnant women who received AMTSL. Our hypothesis is that patients who received oxytocin during the earlystages of labor have a higher risk for PPH due to the presence of an interaction effect given by the oxytocin-induced desensitization.

Material and methods

The Trial for Improving Perinatal Care in Latin America was a multicenter cluster randomized trial in 24 public maternity hospitals in Argentina and Uruguay. The main aim of the trial was to increase the use of two evidence-based birth practices, the use of oxytocin during the third stage of labor and selective episiotomy. For that purpose, the trial evaluated a behavioral intervention to facilitate the development and implementation of evidence-based clinical guidelines regarding the prevention of PPH and the use of episiotomy, compared to usual training activities. A complete description of the trial and the main results have been previously published (14;15). Out of the 24 hospitals that were initially invited to participate in the study, 19 were finally randomized. For this secondary data analysis we used baseline data from the 24 hospitals and post-intervention data from the 19 randomized hospitals. The protocol for this analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the Tulane Office of Human Research Protection.

Study population

A total of 15,263 deliveries were recorded in the final dataset. We excluded 3,690 deliveries that were terminated by cesarean section (24.2%), 14 cases whose birthweight was less than 500 grams (defined as abortion), and 236 cases in which blood loss during the third stage of labor was not registered. After these exclusions, data were available from 11,323 women.

Clinical data collection instruments and database

Although the hospital was the unit of analysis at the end of the trial, individual patient information was collected at the patient level. A standard perinatal clinical history form was designed for the study in which data on obstetric history, prenatal care, labor, delivery and neonatal outcomes were registered. These data were collected directly from the clinical records and the delivery log book from each hospital. For these analyses we included all vaginal deliveries. Data for primary and secondary outcomes and on potential confounders or effect modifiers were collected.

Outcome measurement and definition

Nurses, midwifes and physicians who were part of the teams attending deliveries at participating hospitals were trained in post-partum blood loss measurement. A plastic bag designed to collect blood (drape) was used to collect post-partum blood loss. As soon as the baby was delivered, the drape was placed under the buttock. The blood was allowed to flow into the drape as long as the woman stayed in the delivery chair. After pouring the blood in a calibrated jar, the amount of blood was recorded on the study form and the drape was properly disposed. For the current study, we defined the primary outcome as moderate PPH based on the definition by WHO (≥ 500 ml of blood loss). In addition, severe PPH (≥ 1000 ml of blood loss) and the need of blood transfusion were used as secondary outcome measures.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in STATA, version 9.0. Delivery characteristics were calculated as means and proportions for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Preliminary analyses included univariate and bivariate analyses. Chi-square statistics were used to determine whether the independent variable (use of oxytocin during early stages of labor) was significantly associated with PPH or blood transfusion. Two specific analyses were done in order to evaluate our research question about the potential interaction between the use of oxytocin during the first and second stage of labor and the use of AMTSL with the same drug: 1) stratified analysis in women that received and not received active management of third stage of labor; and 2) multivariate analyses in the whole dataset with the use of interaction terms between induction/augmentation of labor and AMTSL. Due to the fact that the included population was originally from 24 hospitals, we performed cluster regression analyses. Finally, sensitivity analyses were performed comparing the final results of the 24 hospitals with: 1) the five hospitals dropped after baseline collection; 2) the 19 hospitals kept in the main trial.

Power calculations

Based on the following considerations: i) a minimum expected sample size of 2,200 vaginal deliveries that received AMTSL (20% of all expected vaginal deliveries); ii) an estimated prevalence of moderate PPH of 6% (defined as blood loss ≥ 500 ml) in women that received active management of labor; and iii) a relative risk of 1.7 between exposed and non-exposed for oxytocin during early stages of labor, we estimated in advance that the power of the study would be 80% for the analyses restricted to women that received AMTSL.

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of the independent variables in all vaginal deliveries and in women that received and not received oxytocin during the first and second stage of labor. Almost two thirds of the pregnant women received oxytocin during the early stages of labor (induction or augmentation of labor) (N=6,991). In a total of 1,221 vaginal deliveries (10.8%), blood loss was ≥ 500 ml (moderate PPH) and in 209 (1.86%) vaginal deliveries the amount of blood loss was ≥ 1,000 ml (severe PPH). Among all 11,323 vaginal deliveries, only 40 (0.35%) received blood transfusion. However, when we analyzed only the subpopulation that received AMTSL, we found that moderate PPH was 6.7% (275/4,084) and severe PPH was 1.2% (50/4,084). Only 12 patients out of the 4,084 that received AMTSL required blood transfusion (0.29%).

Table 1.

Distribution of different characteristics in the studied population and population characteristics by oxytocin-used during first and second stage of labor

| All vaginal deliveries Number (%)N = 11,323 | No oxytocin during first/second stage of labor Number (%)N = 4,332 | Induced/augmented labor Number (%)N = 6,991 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age Mean (SD) | 24.69 (0.06) | 24.80 (0.09) | 24.63 (0.07) |

| Birthweight Mean (SD) | 3,238 (5.13) | 3,186 (8.93) | 3,271 (6.16) |

| Gestational Age Mean (SD) | 38.6 (0.02) | 38.4 (0.04) | 38.78 (0.02) |

| Parity | |||

| Nullipara | 4,047 (35.7) | 1,290 (29.7) | 2,757 (39.4) |

| 1 – 3 previous para | 5,622 (49.7) | 2,351 (54.3) | 3,271 (46.8) |

| More than 3 previous para | 1,654 (14.6) | 691 (16.0) | 963 (13.8) |

| Birthweight | |||

| Low birth weight (< 2,500 g) | 776 (6.8)) | 381 (8.8) | 395 (5.7) |

| Normal weight | 9,836 (86.9) | 3,703 (85.5) | 6,133 (87.7) |

| Macrosomia (> 4,000 g) | 711 (6.3) | 248 (5.7) | 463 (6.6) |

| Gestational age a | |||

| Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks) | 669 (5.9) | 328 (7.6) | 341 (4.9) |

| Term pregnancy (37 – 41 weeks) | 10,557 (93.3) | 3,980 (91.9) | 6,577 (94.1) |

| Post-term pregnancy (> 41 weeks) | 92 (0.8) | 21 (0.5) | 71 (1.0) |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||

| No | 11,280 (99.6) | 4,316 (99.6) | 6,963 (99.6) |

| Yes | 43 (0.4) | 16 (0.4) | 27 (0.4) |

| Termination | |||

| Spontaneous | 10,960 (96.8) | 4,241 (97.9) | 6,719 (96.1) |

| Operative deliveries | 363 (3.2) | 91 (2.1) | 272 (3.9) |

| Episiotomy | |||

| No | 6,818 (60.2) | 2,816 (65.0) | 4,002 (57.2) |

| Yes | 4,505 (39.8) | 1,516 (35.0) | 2,989 (42.8) |

| Tears | |||

| No | 9,312 (82.2) | 3,610 (83.3) | 5,702 (81.6) |

| First degree | 1,454 (12.8) | 577 (13.3) | 877 (12.5) |

| Second degree | 499 (4.5) | 133 (3.1) | 366 (5.2) |

| Third and fourth degree | 58 (0.5) | 12 (0.3) | 46 (0.7) |

| Active management of third stage of labor b | |||

| No | 7,235 (63.9) | 3,016 (69.7) | 4,219 (60.4) |

| Yes | 4,084 (36.1) | 1,313 (30.3) | 2,771 (39.6) |

| Retained placenta c | |||

| No | 11,174 (99.0) | 4,275 (99.1) | 6,899 (98.9) |

| Yes | 111 (1.0) | 37 (0.9) | 74 (1.1) |

5 missing data

4 missing data

38 missing data

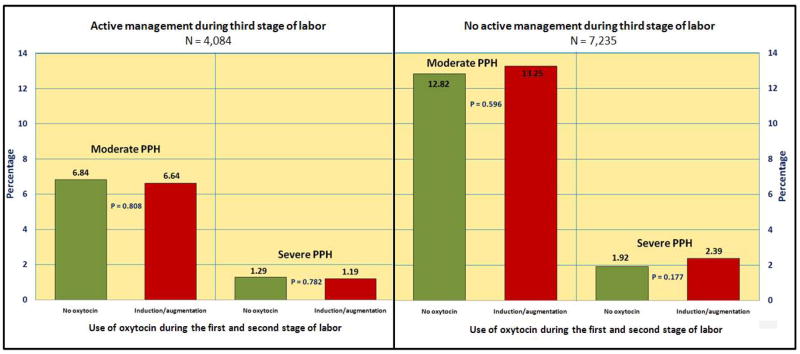

Bivariate analyses between use of active management of labor and use of oxytocin during early stages of labor for PPH are shown in figure 1. In these analyses we did not find any association between the use of oxytocin during early stages of labor and the outcomes when AMTSL was or was not done. Similar results were found when blood transfusion was analyzed as a main outcome (not shown in the figure).

Figure 1.

Moderate and severe postpartum hemorrhage stratified by use of oxytocin during early stages of labor and use of active management of third stage of labor.

The variables associated with PPH were: maternal age, parity, birthweight, gestational age, multiple pregnancy, termination, episiotomy, tears, suture and retained placenta. Since these variables may be interrelated, we performed multivariate analyses in the whole population. An interaction term between the use of oxytocin during the first stage of labor and the use of AMTSL with the same drug was added to the final model. Neither the interaction term nor the main effect for oxytocin during the first/second stage of labor were statistically significant for any of the outcomes (Table 2). A multivariate analysis with and without retained placenta was performed - to consider this event as a potential result of the drug interaction - and the findings were similar. Finally, we performed sensitivity analysis in hospitals kept after the baseline data collection (N=19) and in hospitals dropped after this period (N=5). Despite the loss of power due to sample size reduction, the findings from these analyses were similar to the main results.

Table 2.

Interaction between use of oxytocin during the first and second stage of labor and active management of the third stage of labor. Multivariable analyses (with cluster effect).

| PPH ≥ 500 ml a | PPH ≥ 1000 ml a | Blood transfusion b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Active management of third stage of labor c | 0.49 | 0.34–0.68 | 0.001 | 0.66 | 0.39–1.12 | 0.124 | 0.93 | 0.25–3.49 | 0.917 |

| Oxytocin during first/second stage of labor d | 0.91 | 0.69–1.18 | 0.478 | 1.17 | 0.76–1.79 | 0.474 | 2.00 | 0.74–5.43 | 0.169 |

| Active management of third stage of labor and oxytocin first/second stage of labor e | 0.94 | 0.62–1.41 | 0.753 | 0.66 | 0.32–1.38 | 0.273 | 0.69 | 0.17–2.84 | 0.603 |

PPH: Postpartum hemorrhage, OR: Odds ratio, 95%CI: 95% Confidence Interval.

Adjust for: maternal age, parity, multiple pregnancy, macrosomia, low birth weight, gestational age, episiotomy, tears, suture, forceps and placental retention

Adjust for: maternal age, parity, macrosomia, low birth weight, gestational age, episiotomy, suture, forceps and placental retention

Reference: No active management of third stage of labor

Reference: No use of oxytocin during first/second stage of labor

Reference: No use of oxytocin during any stage of labor.

Comment

The purpose of this report was to evaluate whether AMTSL, as a widely recommend obstetrical intervention, was less effective in preventing PPH in pregnant women that received oxytocin during early stages of labor. Before discussing the findings, the strengths and limitations of our study must be considered. The main strength of this study is the accurate way in which blood loss was measured. The majority of previously reported studies measured blood loss through visual estimation without any objective measurement. In our case, the main cluster randomized controlled trial used a plastic bag specifically designed to collect blood during the third stage of labor for all vaginal deliveries (14). Furthermore, data in this study should be considered of high quality due to the design of a continuous control process within each hospital, and among the main data centre and each hospital in the original trial. All these processes achieved a final dataset with a very low rate of missing data (14). On the other hand, an important limitation of this study is the absence of some variables in the dataset that could be considered important confounding factors for our research question (such as prolonged labor or previous post partum haemorrhage). A further problem with some of the outcomes, such as blood loss transfusion, derives from the fact that the observed number of events was low; therefore, statistical power to detect significant associations was also low.

Our research question was to address the effect of AMTSL in patients that received oxytocin during the first and/or second stage of labor. We hypothesized that women that received oxytocin during early stages of labor could have a different effect when they received active management of labor. The physiological reasoning for this hypothesis was based on the possible binding of the oxytocin receptor by this drug during early stages of labor that could interact with the oxytocin used during the active management of labor. Nevertheless, all the analyses were consistent with the presence of no clinical important differences between pregnant women that received and not received oxytocin during early stages of labor and the use of active management of labor. One limitation from our dataset that may affect our findings is the fact that there was no information about the time that the pregnant women received oxytocin during early stages of labor. This is an important consideration because oxytocin is rapidly metabolized by several enzymes in the kidney and the placenta with a short half-life, therefore, discontinuation of the infusion during induction/augmentation early during labor may reduce the potential interaction effect with the oxytocin in the third stage of labor. Nevertheless, there is some physiological evidence that the oxytocin receptors desensitization occurs during the following 4 hours after the prescription of oxytocin during labor (12). Other findings from our analysis were the description of specific risk factors in our Latin American population, such as: retained placenta, multiple pregnancy, macrosomia, episiotomy, tears, operative delivery and suture. All these risk factors were considered during the analysis in order to avoid important confounder effects that could alter our conclusions.

According to the literature and to our findings (16–18), PPH was more associated with complications of the second or third stage of labor (placental retention, tear, forceps, etc). Most cases of PPH are due to retained placenta, maternal soft tissue trauma, uterine atony or a combination of these factors. We presume that the interaction between the use of oxytocin during different stages of labor and blood loss should be related to uterine atony, and not with maternal soft tissue trauma during delivery. Although uterine atony was not specifically registered as a variable for this study, when we adjusted for retained placenta and maternal soft tissue trauma, we indirectly evaluated the potential effect of uterine atony in this population –as an intermediate variable. Nonetheless, as it was shown, there was no evidence of effect in any of the adjusted analyses. Finally, we explored the possibility that the interaction of oxytocin use in different stages of labor could produce an increase of PPH mediated through the retention of the placenta. Nevertheless, the findings were similar and there was no effect observed between pregnant women that received and those who did not receive oxytocin during the early stages of labor.

In sum, we can conclude that there is no interaction between the use of oxytocics during the first and/or second stage of labor and AMTSL for the outcome PPH. Thus, active management of the third stage of labor should be recommended to any vaginal delivery regardless of whether pregnant women received or not oxytocin during the early stages of labor.

Acknowledgments

Source of the study: Guidelines Trial (U01HD040477).

We would like to thank the NICHD Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research and RTI for allowing us to analyze the dataset from the study “Guidelines Trial” (U01HD040477).

Footnotes

Information for authors: This study was presented as a thesis dissertation at the Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University. New Orleans, United States. May 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Claudio G. SOSA, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, University of Uruguay, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Fernando ALTHABE, Institute of Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

José M. BELIZAN, Institute of Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Pierre BUEKENS, School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, United States.

References

- 1.B-Lynch C, Keith L, Lalonde A, Karoshi M. A text book of Postpartum Hemorrhage. 1. Sapiens Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD000007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prendiville W, Elbourne D, Chalmers I. The effects of routine oxytocic administration in the management of the third stage of labour: an overview of the evidence from controlled trials. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988 Jan;95(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb06475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International joint policy statement. FIGO/ICM global initiative to prevent post-partum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004 Dec;26(12):1100–11. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint statement: management of the third stage of labour to prevent post-partum haemorrhage. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004 Jan;49(1):76–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnay F. Maternal survival in developing countries: what has been done, what can be achieved in the next decade. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000 Jul;70(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalonde A, Daviss BA, Acosta A, Herschderfer K. Postpartum hemorrhage today: ICM/FIGO initiative 2004–2006. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006 Sep;94(3):243–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker S, Loper D. Maternal, Fetal, and Neonatal Physiology. 1. W.B. Saunders Company; 1992. Parturation and Uterine Physiology; pp. 109–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):386–97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b48ef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser W, Vendittelli F, Krauss I, Breart G. Effects of early augmentation of labour with amniotomy and oxytocin in nulliparous women: a meta-analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Feb;105(2):189–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson C, Schumann R, Zhang P, Young RC. Oxytocin-induced desensitization of the oxytocin receptor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Feb;188(2):497–502. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Zeno JA, Peaceman AM, Adashek JA, Socol ML. A controlled trial of a program for the active management of labor. N Engl J Med. 1992 Feb 13;326(7):450–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202133260705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althabe F, Buekens P, Bergel E, Belizan JM, Kropp N, Wright L, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to facilitate the development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines in Latin American maternity hospitals: the Guidelines Trial: Study protocol [ISRCTN82417627] BMC Womens Health. 2005 Apr 11;5(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Althabe F, Buekens P, Bergel E, Belizan JM, Campbell MK, Moss N, et al. A behavioral intervention to improve obstetrical care. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358(18):1929–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa071456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK., Jr Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jan;77(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK., Jr Factors associated with hemorrhage in cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jan;77(1):77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sosa CG, Althabe F, Belizan JM, Buekens P. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in vaginal deliveries in a Latin-American population. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;113(6):1313–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a66b05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]