Abstract

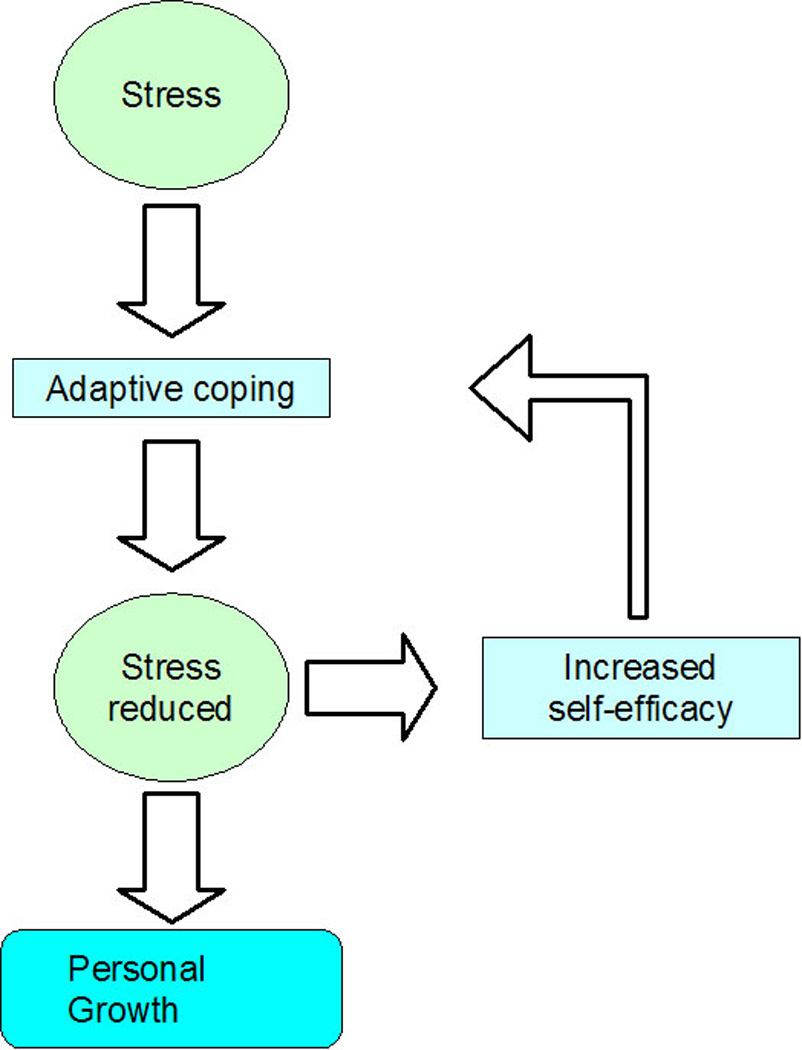

The literature has shown that long-term outcomes for both below-knee amputation and reconstruction following type III-B and III-C tibial fracture are poor. Yet, patients often report satisfaction with their treatment and/or outcomes. The aim of this study is to explore the relationship between patient outcomes and satisfaction after open tibial fractures via qualitative methodology. Twenty patients who were treated for open tibial fractures at one institution were selected using purposeful sampling and interviewed in-person in a semi-structured manner. Data were analyzed using grounded theory methodology. Despite reporting marked physical and psychosocial deficits, participants relayed high satisfaction. We hypothesize that the use adaptive coping techniques successfully reduces stress, which leads to an increase in coping self-efficacy that results in the further use of adaptive coping strategies, culminating in personal growth. This stress reduction and personal growth leads to satisfaction despite poor functional and emotional outcomes.

Keywords: lower leg trauma, amputation, reconstruction, coping, qualitative research

Type III-B and III-C fractures are among the most serious trauma an individual can experience. Fractures of this type can be managed with either below-knee amputation or complex reconstructive procedures. Both treatment methods require extensive hospital stays and years of rehabilitation and additional treatment. Our utility survey showed that patients and physicians favor reconstruction over amputation,(1) but outcomes are uncertain regardless of which treatment method is chosen.(2) The Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP), a multi-center, prospective study of patients with severe injuries below the level of the distal femur, followed over 600 patients for nearly a decade and discovered that long-term functional outcomes are poor in both groups. (3, 4)

These, and other, research findings suggest that lower-extremity trauma is a devastating injury that leaves patients broken physically, psychologically and financially. Conversely, however, multiple studies have reported that patients are actually quite satisfied following treatment. Hoogendoorn et al. found that over 80% of patients interviewed reported satisfaction with their treatment, although they do note that this high satisfaction rate indicates satisfaction with treatment, not necessarily with treatment outcomes.(5) However, the LEAP Study found that 66% of patients responded that they were very or completely satisfied when asked, two years after injury, “Overall, how satisfied are you with the progress you have made in recovering from your injuries?”(6) All despite functional outcomes that appear dismal. There is some evidence that some patients’ satisfaction may even extend beyond satisfaction to a sense of personal growth. A 2007 survey of patients who had experienced severe orthopedic trauma due to motor vehicle accidents in the preceding 4 years found that although 87% reported ongoing physical difficulties and 62% reported ongoing psychological difficulties, 99% reported that they felt they had experienced personal growth due to their injuries.(7) For a life-altering traumatic event such as open tibial fracture, the full spectrum of factors contributing to patients’ recovery and well-being may not be fully captured by using quantitative methods, such as physical measurements and outcomes questionnaires, alone. The specific aim of this study is to conduct a qualitative analysis of the patient experience, including satisfaction following type III-B or III-C fracture of the tibia.

Materials and Methods

Previous research exploring the psychological experiences of patient with severe lower limb trauma has used quantitative methodology,(8–10) which cannot provide the rich, intricate details that qualitative methods can.(11) Quantitative methodology has reveled that there are significant psychological sequelae after severe lower limb injury. (8–10) But quantitative methodology cannot define how these sequela plays out in the recovery process; it can only show that they do indeed exist. We chose to use qualitative methodology which is ideal for shining light on complex issues, such as coping and emotional recovery, that can be difficult to assess with quality of life surveys or psychological inventories.(11)

We used grounded theory to guide our research. Grounded theory is characterized by the lack of hypotheses at the beginning of the project.(11) This does not mean that research is begun aimlessly, but that there is only a focus and no preconceived notions about what one might discover. Through the process of analyzing interview data, a theory is allowed to emerge. The theory that is developed using grounded theory will often more closely resemble “reality” than one that is developed a priori.(11)

Study Sample

We used purposive sampling methodology to select our study sample. Purposive sampling differs from random sampling, generally used in quantitative research, in that participants are chosen because the represent a particular characteristic that one wishes to study.(12) We chose to use purposive sampling because we wanted to ensure that our sample included patients who had been treated with successful reconstruction, reconstruction attempt with secondary amputation and primary amputation. We also wanted to interview patients with a wide range of complications.

We began our purposive sampling with patients who had undergone treatment for type III-B or III-C fractures of the tibia at the University of Michigan between 1997 and 2007. Patients were excluded if they suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) concurrently. The myriad of issues inherent to recovery from TBI have been well documented(13) and we felt that the experience of patients recovering from this type of injury would differ drastically from patients without such injuries. We also excluded patients who were involved in fatality accidents because we felt that recovering from a personal loss may require substantial emotional energy, thus confounding the coping with the physical injury. We ultimately selected 20 patients to interview. Participants received a $100 grocery gift card to thank them for their time. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Interviews took place in-person at the University of Michigan. To maintain consistency, one member of the research team (MSA) conducted all interviews. Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner, meaning that questions were open-ended and participants were encouraged to elaborate on their responses and were to discuss topics in whatever cognitive order they preferred..(14) An interview guide was used, focusing on various areas of the participants’ lives that may have been affected by their injury and participants’ feelings about the medical treatment they received and their decision-making process related to choice of treatment. The latter two topics were examined in an analysis separate from this one. For all questions, participants were encouraged to compare their experiences before and after their injury.

Data Analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Following grounded theory, data analysis was achieved in a step-wise process.(11) First, transcribed interviews were read by two member of the research team (MJS, MSA). During this first reading, open coding was performed. Open coding is the process of identifying sentences or passages that represent key concepts.(11) After open coding of all transcripts was completed, the research team met to discuss the open coding and to construct the codebook, including categories, codes and sub-codes. Transcripts were then reread and the codebook was applied in the process of focus coding, which is the process by which the agreed up codes are applied to sentences and passages in transcripts. (11) Following focus coding, the research team met again to discuss any discrepancies. The final, agreed upon coded transcripts were then analyzed to discover which codes appeared the most frequently and if they appeared in conjunction with other codes.

Results

Participants were interviewed an average of 6.8 years (range: 2.3 – 12.0) following injury. Interviews averaged 31:09 minutes in duration (range: 13:22 – 77:06). Participant demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Information

| Patient Information (n=20) | ||

| Gender Distribution (M/F) | 15/5 | |

| Mean age (range) | 47 (23 – 68) | |

| Injury information (n=23) | ||

| Bilateral injuries | 3 | |

| Fracture type | ||

| III-B | 17 | |

| III-C | 6 | |

| Treatment type | ||

| Primary amputation | 4 | |

| Reconstruction | 14 | |

| Secondary amputation | 5 | |

| Mean duration to 2° amputation (range) | 30 weeks (2 – 72) | |

| Injury Cause | ||

| Motor vehicle accident | 12 | |

| Crush injury | 3 | |

| Fall from height | 3 | |

| Pedestrian hit by vehicle | 2 | |

| Additional Orthopedic Injuries | ||

| Ipsilateral femur fracture | 8 | |

| Upper extremity fracture | 4 | |

| Ipsilateral foot fracture | 3 | |

| Pelvic fracture | 3 | |

| Vertebrae fracture | 2 | |

| Major Complications | ||

| Nonunion | 11 | |

| Flap failure | 5 | |

| Osteomyelitis | 3 | |

| Secondary revision of amputation | 2 | |

| Necrotizing Fasciitis | 1 | |

Twenty-three codes emerged in 3 broad categories: 1) Effects on Life, 2) Medical Treatment and 3) Medical Decision-Making. As previously mentioned, this analysis will focus Effects on Life. This category was broken down into 9 specific codes, shown in Table 2. We present highlights and representative quotes on physical outcomes are presented in Table 3, work-related outcomes in Table 4 and psychosocial outcomes in Table 5.

Table 2.

Codes clarifying the effect of type III-B and III-C fractures on participants' lives Physical functioning

| Physical functioning |

| Pain |

| Energy |

| Work |

| Impact on family |

| Body image |

| Social life |

| Other’s reactions to injury |

| Overall life effects |

Table 3.

Remarks and Representative Quotes Relating to Physical Outcomes

Physical Functioning

|

Pain

|

Energy

|

Table 4.

Remarks and Representative Quotes Relating Work-Related Outcomes

|

Table 5.

Remarks and Representative Quotes Relating to Psychosocial Outcomes

Body Image

|

Social Life

|

Other’s Reactions to Injury

|

Satisfaction

Our patients, like those reported in other studies, reported satisfaction with their treatment and/or outcomes. Overall, 80% of participants reported that they were satisfied with their outcomes and/or treatment. Only 1 participant who received reconstructive surgery was satisfied with neither his treatment nor his outcomes. Likewise, only 1 participant who received secondary amputation was equally dissatisfied with his treatment and outcomes. For participants receiving primary amputation, 2 were dissatisfied with their outcomes, but did express satisfaction with the treatment they received. Representative quotes are shown in Table 6

Table 6.

Representative Quotes Relating to Satisfaction

Satisfaction

|

Coping

The use of qualitative methodology has shed some light upon the apparent paradox between outcomes and patient satisfaction. Existing literature, using quality of life questionnaires and Likert scale satisfaction questions could not reconcile the fact that physically, and often emotionally, patients’ quality of life is suboptimal, yet they still report high satisfaction. The use of qualitative methodology has shed some light upon this apparent paradox. A factor that quality of life questionnaires cannot expose is coping, the process of managing unpleasant circumstances to minimize or elevate the stress that these circumstances cause.(15) While examining and coding our participants’ responses to our questions, a number of coping strategies began to emerge, despite the fact that we never explicitly asked about coping. These responses were consistent with the Approach/Avoidance coping framework. As the name would suggest approach strategies confront the stressor and are considered to be more adaptive, whereas avoidance strategies tend to circumvent the stressor, which is seen as more maladaptive.(16) Both strategies can be defined as problem-focused or emotion-focused. Representative quotes are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Representative Quotes Relating to Coping

Approach Coping

|

Avoidance Coping

|

Approach Coping

Approach coping focuses on understanding and dealing with the stressor head-on. In a problem-focused manner this may involve practical problem-solving. Several participants reported modifications to their homes or vehicles, and nearly every participant mentioned learning new ways to preform everyday tasks or changes.

Another problem-focused approach coping strategy is cognitive restructuring, the process of recognizing the positive aspect of a negative situation. Many participants exhibited this by comparing their current situation with death; 85% of participants mentioned at least once that they were thankful to be alive or that they saw their injuries as a more favorable alternative to death. Cognitive restructuring was also demonstrated by participants receiving disability payments, who felt fortunate to have any income because they felt they would have been unemployed otherwise due to the economy. Finally, a few participants noted that although they continued to have pain, they chose to view it not as an affliction caused by their injury, but as something that would have occurred as part of the normal aging process.

Emotion-focused approach coping is characterized by the expression of emotion and the seeking of social support. When participants were asked about the emotional impact of their injuries, the majority allowed that they often felt frustrated that they could not perform activities that they used to engage in. Four participants mentioned feeling depressed soon after their injury, but very few participants discussed the actual expression of emotion.

Similarly, despite being questioned about the impact of their injuries on their social lives, very few patients explicitly mentioned relying on the support of others. One participant mentioned that her friends had been a source of support, and another relayed thankfulness that her siblings were able to help her physically and emotionally. But spouses were the most frequently mentioned source of support. 60% of our participants were currently married, and interestingly all mentioned during the interview how long they had been married, perhaps indicating the importance of spousal support in the eyes of our participants.

Avoidance Coping

Avoidance coping is characterized by attempts to steer clear of the stressor or its effects. For a stressor such as open lower leg fracture problem-focused avoidance coping techniques, particularly denial that the stressor exists, are highly difficult, if not impossible to achieve. Several participants reported engaging in some degrees of problem avoidance, by avoiding situations that are now too difficult or that would highlight the participants’ injury or disability. Emotion-focused avoidance coping strategies were expressed by several participants in one form or another. For example, three participants with amputations engaged in self-criticism, focused primarily on the perception from the popular media that many amputees are able to compete in athletics at a high level. Withdrawing from sources of possible social support is another emotion-focused coping strategy. At the extreme end of avoidance coping, one participant denied that he felt any emotion toward his injury at all. Overall, though, avoidance coping was seldom expressed by our participants. Given the correspondingly high satisfaction that participants relayed, it is possible that high patient satisfaction is not the result of superior outcomes, but the result of frequent use of adaptive coping strategies.

Self-Efficacy

Another concept related to coping is self-efficacy, the belief that one is capable of performing a particular action at a particular level. The LEAP study found that patients who expressed less self-efficacy over their physical recovery displayed more symptoms of anxiety and depression two years after injury and had a higher level of functional disability seven years after injury.(9),(17) None of our participants relayed feelings of self-efficacy for coping with the aftermath of their injuries, but it is conceivable that low self-efficacy for emotional recovery can have similar negative effects as low self-efficacy for physical recovery.(18) Representative quotes are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Representative Quote Relating to Self-Efficacy

|

Personal Growth

Through our analysis a relationship emerged between coping and self-efficacy leading to the best possible outcomes following this life-altering trauma. Some of our participants seemed to be not only surviving their open tibial fractures, they were appearing to thrive, not in spite of the trauma they had been through, but because of it. Anecdotal and scientific evidence show that some people are strengthened after facing severe mental or physical adversity(7, 19, 20) and our participants seemed to be among them. Three participants explicitly expressed that they have grown personally as a result of their injuries. One, who had undergone successful reconstruction after a motorcycle accident, attributed the accident to his decision to stop drinking and to renew his relationship with his religion.

The other two participants were remarkably similar. Both were 24-years-old when they had crush injuries in industrial accidents. Both could no longer perform the physical demands of manual labor and opted to attend college and become teachers. Some of their personal growth could simply be the increased security and sense of self that occurs during one’s mid to late 20s, but both men strongly attribute this growth to their experiences during recovery from their injuries. Representative quotes are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Representative Quotes Relating to Personal Growth

|

Cognitive Framework

Examining the data with coping strategies in mind allowed a cognitive framework to emerge, demonstrating the possible interplay between the physical, social, financial and emotional stress of a severe open tibial fracture, the use of adaptive coping strategies, coping self-efficacy and finally, personal growth. (Figure 1) We hypothesize that positive coping strategies, such as directly confronting the problem, either using problem-focused or emotion-focused approach coping strategies, leads to an alleviation of the stress caused by the injury and its effects. The successful use of positive coping strategies to reduce stress leads to increased self-efficacy for coping with the injury. This leads to the further use of adaptive coping strategies, the further reduction of stress and continuing increase in self-efficacy. Finally, in some cases, this cycle can lead to personal growth, like that seen in three of our participants.

Figure 1.

Cognitive Framework showing the relationship between stress, adaptive coping, self-efficacy and personal growth.

Discussion

Despite ever-emerging new technology the outcomes of type III-B and III-C tibial fractures are not improving. The LEAP study found that regardless of the treatment method used two years after injury only about half of the patients had returned to work and more than 40% had Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) scores that indicated severe disability. (21) Seven years after injury only 58% of patients had returned to work and nearly 50% had SIP scores indicating a severe disability.(17, 22) Inability to work and severe disability can affect patients financially; 57% of patients who sustained lower-extremity injuries in motor vehicle accidents would describe the financial impact of their injury as moderate to severe.(8) Physical disability is not the only long-term effect. Hoogendoorn et al. found that three years after injury 46% of reconstructed patients and 39% of amputees still experience occasional pain.(5) Fourteen percent and 11%, respectively, still experience continuous pain.(5) Furthermore, two years after injury nearly 40% of patients in the LEAP study still report moderate to severe psychological distress, including somatic symptoms, depression and anxiety.(9) A Swiss study found that one-third of patients felt that they were less sexually attractive than prior to the injury and about half said that they felt “insecure in their social relations.”(10)

Despite these poor outcomes, over 60% of patients report satisfaction with their treatment and/or outcomes.(5, 6) We found similar results. Eighty percent of the patients we interviewed reported satisfaction with their treatment and/or outcomes. This is despite the fact that 100% reported at least some continued impairment to physical functioning and 95% reported that they still had at least occasional pain related to their injury.

This study is not without limitations. There may have been several factors confounding the high level of satisfaction among our participants. First, it is unlikely that participants who were highly dissatisfied with their treatment or outcomes, or who were experiencing significant emotional distress related to the injury, would volunteer to return for an interview. Secondly, our participants were interviewed at least 2 years after injury. This long follow-up time may have given participants time to overcome much of the initial shock of the injury. However, we feel that this is not necessarily negative. The average age of open tibial fracture patients is 43 years.(23) Many of these patients have a long life ahead of them. They will spend many more years in the “post-shock” phase than in the first 24 months after injury.

Using qualitative methodology allowed us to explore the personal experiences of patients recovering from type III-B and III-C tibial fractures, an injury with a generally poor functional prognosis regardless of treatment method. (17, 21, 22) By asking patients to describe their own experiences, we were able to not only get a more personal glimpse of the physical and psychosocial difficulties that prior research has shown to exist, we were able to explore the apparent paradox between low functional and quality of life outcomes and high patient satisfaction. We hypothesize that satisfaction may come as a results of the use of adaptive coping strategies, which successfully alleviates the life stress that can result from a serious injury such as open tibial fracture. Additional research will allow us to explore these topics further and to test our hypothesized relationship between self-efficacy, coping and personal growth and to explore possible interventions that can detect maladaptive coping strategies, help patients make the most of adaptive coping strategies and to help build coping self-efficacy.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the support from the National Endowment for Plastic Surgery and a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chung KC, Shauver MJ, Saddawi-Konefka D, et al. A decision analysis of amputation versus reconstruction for severe open tibial fracture from the physician and patient perspectives. Ann Plast Surg. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181cbfcce. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saddawi-Konefka D, Kim HM, Chung KC. A systematic review of outcomes and complications of reconstruction and amputation for type IIIB and IIIC fractures of the tibia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1796–1805. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818d69c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, et al. Characterization of patients with high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:455–466. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacKenzie EJ, Jones AS, Bosse MJ, et al. Health-care costs associated with amputation or reconstruction of a limb-threatening injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1685–1692. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoogendoorn JM, van der Werken C. Grade III open tibial fractures: functional outcome and quality of life in amputees versus patients with successful reconstruction. Injury. 2001;32:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Toole RV, Castillo RC, Pollak AN, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction after severe lower-extremity injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1206–1211. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harms L, Talbot M. The aftermath of road trauma: survivors' perceptions of trauma and growth. Health Soc Work. 2007;32:129–137. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Read KM, Kufera JA, Dischinger PC, et al. Life-altering outcomes after lower extremity injury sustained in motor vehicle crashes. J Trauma. 2004;57:815–823. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000136289.15303.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Edwin D, et al. Psychological distress associated with severe lower-limb injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1689–1697. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertel R, Strebel N, Ganz R. Amputation versus reconstruction in traumatic defects of the leg: outcome and costs. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:223–229. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman D, Marvasti A. Doing qualitative research: A comprehensive guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. Selecting a case. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marion DW. Introduction. In: Marion DW, editor. Traumatic brain injury. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishing; 1999. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillham B. Research interviewing: The range of techniques. Berkshire, England: Open University Press; 2005. The semi-structured interview; pp. 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. The concept of coping; pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littleton H, Horsley S, John S, et al. Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:977–988. doi: 10.1002/jts.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, et al. Long-term persistence of disability following severe lower-limb trauma. Results of a seven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1801–1809. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benight CC, Cieslak R, Molton IR, et al. Self-evaluative appraisals of coping capability and posttraumatic distress following motor vehicle accidents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ubel PA. You're stronger than you think: tapping into the secrets of emotionally resilient people. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruane ME. From wounds, inner strength. Washington, DC: Washington Post; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation of leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1924–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, et al. Factors influencing the decision to amputate or reconstruct after high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Trauma. 2002;52:641–649. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Court-Brown CM, Rimmer S, Prakash U, et al. The epidemiology of open long bone fractures. Injury. 1998;29:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]