Abstract

Clinical and laboratory evidence suggests that alcohol consumption dysregulates immune function. Burn patients who consume alcohol before their injuries demonstrate higher rates of morbidity and mortality, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, than patients without alcohol at the time of injury. Our laboratory observed higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and leukocyte infiltration in the lungs of mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury than with either insult alone. To understand the mechanism of the increased pulmonary inflammatory response in mice treated with ethanol and burn injury, we investigated the role of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1. Wild-type and ICAM-1 knockout (KO) mice were treated with vehicle or ethanol and subsequently given a sham or burn injury. Twenty-four hours postinjury, lungs were harvested and analyzed for indices of inflammation. Higher numbers of neutrophils were observed in the lungs of wild-type mice after burn and burn with ethanol treatment. This increase in pulmonary inflammatory cell accumulation was significantly lower in the KO mice. In addition, levels of KC, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 in the lung were decreased in the ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Interestingly, no differences were observed in serum or lung tissue content of soluble ICAM-1 24 hours postinjury. These data suggest that upregulation of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 on the vascular endothelium may play a critical role in the excessive inflammation seen after ethanol exposure and burn injury.

Burn injury has been shown to cause an enhanced systemic inflammatory response leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and multiple organ failure. 1,2 This dysregulated immune response in humans and mice can be characterized by higher levels of proinflammatory cytokine production and a suppressed cellular immune response.3 The suppression of the immune response observed after burn is exaggerated with the addition of alcohol resulting in increased morbidity and mortality.4–6 Major postinjury complications result from sepsis and pulmonary failure, 7 most likely resulting from bacteria and endotoxin leaking from the gut to the lungs, increased risk of contact with pathogens from both the circulation and the airway, and the delicate architecture of the lung itself. In animal models, increased neutrophils were observed in the lungs of both mice and rats after burn injury.8,9 In addition to facilitating clearance of pathogens from the lungs, neutrophils can also cause tissue damage through the release of soluble toxic mediators, such as reactive oxygen species and elastase.10,11 Neutrophil accumulation is often used as a marker for remote organ damage after burn injury.12,13

Increased neutrophil extravasation into the lung is a result of multiple factors including increases in chemokine secretion, adhesion molecule expression, and vascular permeability. This study focused on the role of adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, in the aberrant pulmonary inflammation observed after ethanol exposure and burn injury. ICAM-1 binds LFA-1 or MAC-1 (CD11a or CD11b) on the surface of circulating leukocytes and is important as both a costimulatory and adhesion molecule recruiting immune cells to the site of inflammation. 14 Both in vitro and in vivo work demonstrate that immune cell-adhesion molecule interactions are altered with physiological doses of ethanol,15 which may play a role in the increased innate cell infiltration and inflammation observed after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Although normal expression of ICAM-1 is very low or nonexistent, it is upregulated during inflammation16,17 and has been shown to be increased in the lungs after burn alone18 and after ethanol exposure and burn injury.9 In addition, increased expression of the ICAM-1 receptor, CD11/CD18, was also found on peripheral neutrophils after burn.18 Consistent with these observations, clinical studies found increased soluble ICAM (sICAM)-1 in the serum of burn patients19 and patients with acute lung injury.20 sICAM-1 can also be found in murine models of lung injury and fibrosis.21 Moreover, in a mouse model of sepsis, ICAM-1 was shown to be crucial for the systemic inflammatory response and neutrophilia observed in the lung.22 Blocking by monoclonal antibody or use of ICAM-1 knockout (KO) mice showed decreased neutrophil accumulation in models of bleomyin-induced and pancreatitis-associated lung injury.23,24 Therefore, ICAM-1 may play a crucial role in distal organ inflammation observed after injury.

Based on observations that ICAM-1 is elevated in the lung after ethanol exposure and burn injury,9 we hypothesized that mice deficient in ICAM-1 would display a blunted inflammatory response after the combined insult. By using a murine model of acute ethanol exposure and burn injury, we demonstrated that the combined insult of ethanol and burn results in increased proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, in the circulation at 24 and 48 hours postinjury. 25–27 In addition, we showed that at early time points after injury (2–24 hours), there is a significant increase in the number of neutrophils present in the lung interstitium.8 The studies described below expand on the previous observations by examining the role of ICAM-1 in the excessive pulmonary inflammation after the combined injury of ethanol and burn. Wild-type mice had increased chemokine and cytokine levels and neutrophil infiltration in the lungs after ethanol exposure and burn injury compared with sham animals and animals receiving burn alone. However, the ICAM-1 KO mice had significantly reduced levels of pulmonary inflammatory mediators and leukocyte emigration in the lung interstitium, indicating an important role for this molecule in the aberrant pulmonary inflammation observed in our model of ethanol exposure and burn injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Male wild-type (C57BL/6) and ICAM-1 KO (B6.129SR-Icam1tm1Jcgr/J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The ICAM-1 KO mice were created by the insertion of a neomycin-resistance cassette into exon 4 of the ICAM-1 gene.28 Mice were housed in sterile microisolator cages under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Loyola University Medical Center Comparative Medicine facility. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine Model of Ethanol Exposure and Burn Injury

A murine model of a single (acute) ethanol exposure and burn injury was performed as described previously.8,29 Briefly, mice were given a single dose of 1.11 g/kg of 20% (vol/vol) ethanol solution given intraperitoneally that resulted in a blood ethanol level of 150 to 180 mg/dl at 30 minutes. The mice were then anesthetized with 50 mg/kg of Nembutal (Webster Veterinary, Sterling, MA), their dorsum shaved, and placed in a plastic template exposing 15% of the TBSA and subjected to a scald injury in a 92 to 95°C water bath or a sham injury in room temperature water. The scald injury resulted in an insensate, full-thickness burn injury of ~15% TBSA.30

Histopathologic Examination of the Lungs

At 24 hours postinjury, mice were killed by CO2 narcosis, and the lungs were harvested. The upper right lobe was inflated with 10% formalin and fixed overnight as described previously.8 The lung was then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The sections were analyzed microscopically in a blinded fashion for pathologic changes, and numbers of neutrophils in 10 high-power fields were counted as a marker of inflammation.8 The degree of vascular congestion was evaluated by a pathologist in a blinded manner. The sections were given scores from 0 to 4 based on the expansion of the alveolar walls by red blood cells and neutrophils within the capillaries. The number and morphology of the red blood cells and the number of neutrophils present in the capillary and alveolar walls were evaluated as follows: no congestion (0), slightly widened alveolar walls by attenuated or flattened erythrocytes, no neutrophils (1), expanded alveolar wall containing erythrocytes with a rounded morphology and mild congestion (2), expanded alveolar wall containing a row of rounded erythrocytes with moderate congestion with or without rare neutrophils (3), and expanded alveolar wall containing a row of rounded erythrocytes (4), moderate to severe congestion with multiple neutrophils present in the vascular and alveolar walls. The scores were then averaged within each treatment group.

Immunofluorescent Staining of Neutrophils in the Lung

The lower left lobe was inflated with 25% OCT freezing medium (Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) in phosphate-buffered saline, then embedded in OCT and frozen for immunofluorescent staining of cells as described previously.31 The lung was then sectioned (5 µm) and stained using rat anti-Gr-1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by goat antirat IgA conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) to detect Gr-1 positive neutrophils. The sections were also stained with biotinylated anti-MOMA-2 antibody (BMA Biomedicals, Augst, Switzerland), a pan-macrophage marker, and detected with Cy3 streptavidin (Invitrogen).

Cytokine Analysis of Lung Homogenates

In the same animals, the middle right lobe was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 1 ml of BioPlex cell lysis buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The homogenates were then filtered and analyzed for cytokine production using BioPlex multiplex bead array. The results were normalized to total protein present in the homogenate using the BioRad protein assay based on the methods of Bradford32 (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Quantification of IL-6 in Serum

For measurement of IL-6, blood was obtained from cardiac puncture after sacrifice, allowed to clot for 20 minutes at room temperature, and centrifuged (3000 rpm for 20 minutes) to obtain serum. IL-6 levels were then determined by multiplex bead array according to kit instructions (Invitrogen). The multiplex array also measured levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which were below the limit of detection (8–14 pg/ml).

Determination of Circulating Leukocytes

Approximately 100 µl of whole blood was collected in an EDTA-treated microcuvette (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Total and differential counts were then obtained using a Hemavet 950 machine (Drew Scientific, Inc., Oxford, CT) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Data are shown as total cell counts in thousands of cells per microliter.

Soluble ICAM-1 ELISA

sICAM-1 levels were detected in serum and lung homogenates of wild-type mice using an ELISA kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The lower limit of detection for this assay is 5 ng/ml. The range of sICAM-1 determined for ICAM-1 KO mice in the serum was 0 to 0.9 µg/ml and for lungs 14.4 to 19.8 µg/mg protein.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were made between wild-type and KO animals in the sham vehicle, sham ethanol, burn vehicle, and burn ethanol treatment groups, resulting in 8 total groups analyzed. One-way analysis of variance was used to determine differences between treatment responses, and then, Tukey’s post hoc test once significance was achieved (P < .05).

RESULTS

Changes in Lung Histopathology After Acute Ethanol Exposure and Burn Injury

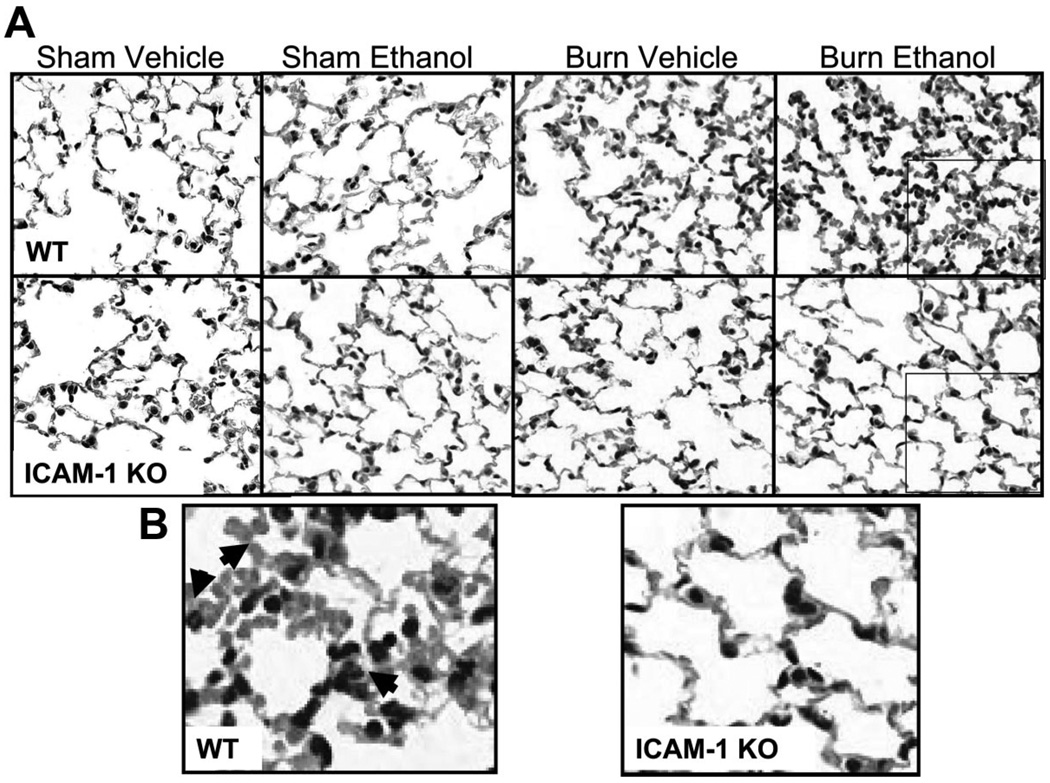

Previous studies by our laboratory showed increases in both pathology and inflammatory cell infiltrate in the lungs of mice exposed to acute ethanol exposure and burn injury.8 ICAM-1 binds CD11a (LFA-1) on the surface of neutrophils allowing them to extravasate into the site of injury. To determine if ICAM-1 was important in aberrant pulmonary inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury, lungs from wild-type and ICAM-1 KO mice were examined histologically for indices of inflammation including leukocyte infiltration, alveolar wall thickness, and airway congestion (Figure 1). At 24 hours after 15% TBSA burn injury, lungs from wild-type mice appeared to have thickened alveolar and capillary walls and increased numbers of leukocytes both in the capillaries and the interstitium (Figure 1B). This increased inflammation was more pronounced in wild-type mice receiving ethanol before burn. The addition of ethanol alone did not alter lung morphology, so that lungs from mice in the sham ethanol group resembled mice in the sham vehicle control group. In contrast to wild-type mice treated with acute ethanol and burn-injury, the lungs from ICAM-1 KO mice given either burn alone or ethanol and burn injury showed attenuated pulmonary inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury, resembling sham animals (Figure 1C). The lung sections were also given a congestion score from 0 to 4 based on the presence of rounded erythrocytes and neutrophils in the capillaries and alveolar walls. Consistent with the morphological changes, lungs from wild-type mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury had a higher congestion score (4 ± 0) compared with sham wild-type animals (0.7 ± 0.3) and mice receiving burn injury alone (2.3 ± 0.8). Interestingly, the ICAM-1 KO mice received similar congestion scores regardless of treatment (2 to 2.5 ± 0.5).

Figure 1.

Inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury in the lung. A, Lung sections from wild-type (WT) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 knockout (ICAM-1 KO) mice were examined for degree of inflammation 24 hours after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Representative micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin lung sections are shown. All images are at magnification, 400×. B, Enlarged image of lung sections in A from WT and ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Arrowheads indicate areas of neutrophils and thickened alveolar walls.

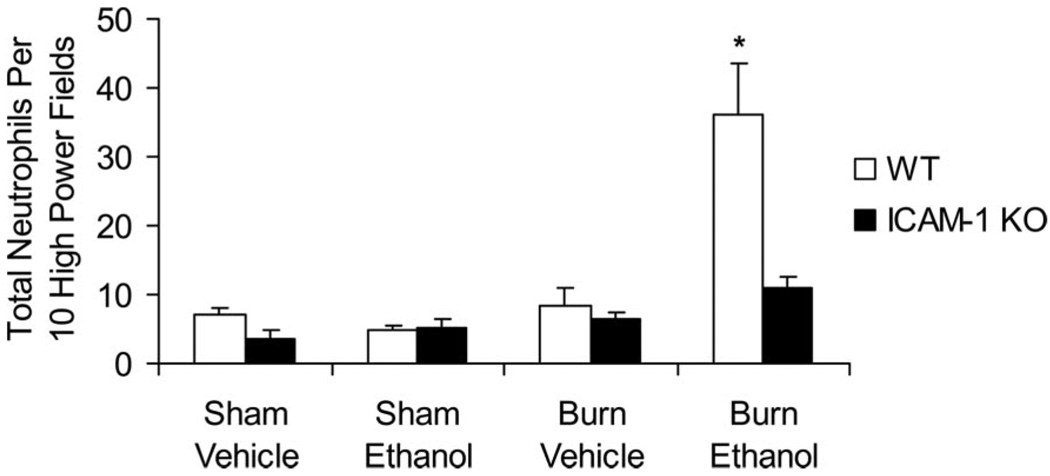

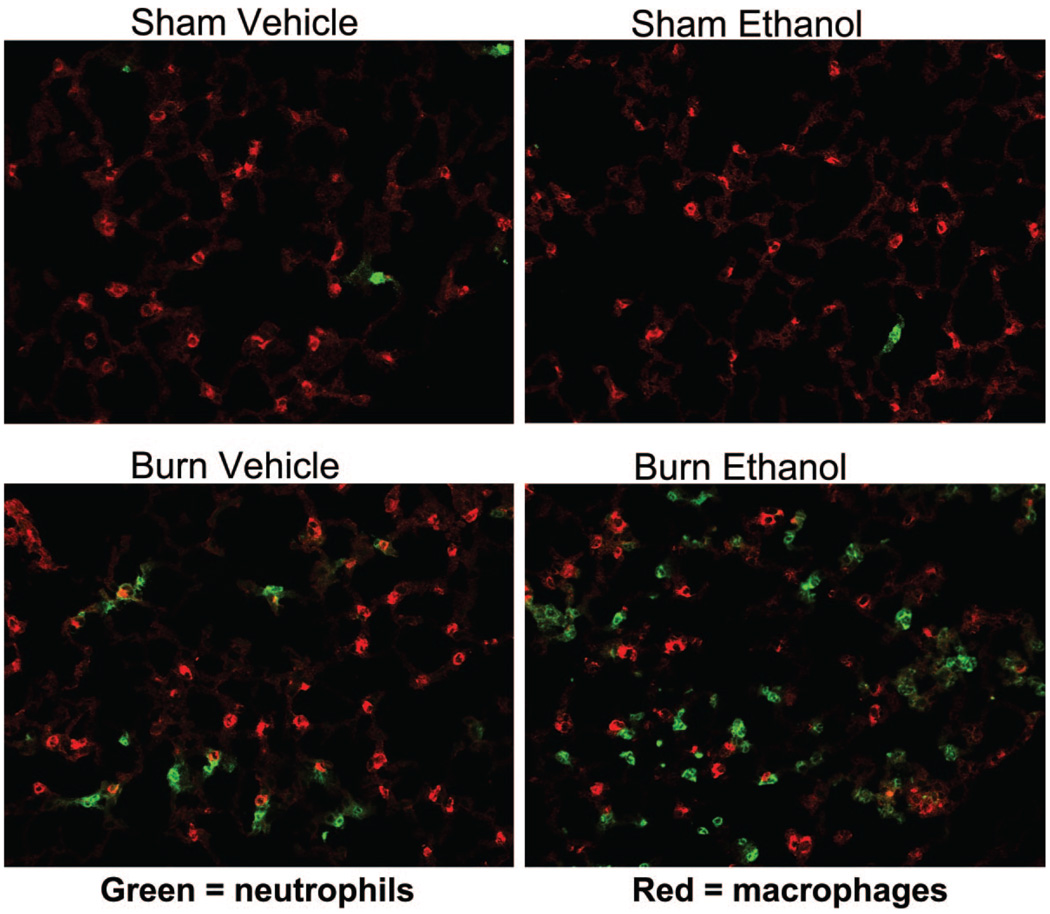

On closer examination of the H&E-stained lung sections (400×), the infiltrating cells appeared morphologically similar to neutrophils with segmented nuclei (data not shown). The number of neutrophils in 10 high-power fields of the H&E-stained sections were counted as described previously.8 We observed an 8-fold increase in the number of neutrophils present in the lungs of ethanol-treated and burn-injured wild-type mice compared with sham animals (P < .001; Figure 2). The combined insult also resulted in 4-fold higher numbers of neutrophils than in mice receiving burn injury alone. In contrast, ICAM-1 KO mice had low levels of neutrophils present regardless of treatment group, with 70% fewer cells observed in KO mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury compared with their wild-type counterparts (P < .001). Similar levels of neutrophils were present in both wild-type and ICAM-1 KO animals after burn alone. To confirm that these infiltrating cells were indeed neutrophils, we stained frozen lung sections with antibodies specific for neutrophils (Gr-1–green) and macrophages (MOMA-2–red). There was a marked increase in the number of cells staining for the green Gr-1 marker, indicating the presence of neutrophils in the lungs of ethanol- and burn-treated wild-type mice and wild-type mice treated with burn injury alone (Figure 3). No differences were observed in the number of MOMA-2+ macrophages.

Figure 2.

Neutrophil infiltration in the lung. Neutrophils were counted by light microscopy in hemotoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections 24 hours after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Data are shown as the total number of neutrophils in 10 high-power fields (magnification, 400×) ± SEM. *P < .001 compared with all groups. N = 7–12 animals per group.

Figure 3.

Neutrophil infiltration after ethanol exposure and burn injury in the lung. Lung sections from wild-type (WT) were stained by flurochrome-conjugated antibodies against Gr-1 (green) and MOMA-2 (red) to detect the presence of neutrophils and macrophages, respectively. Representative micrographs are shown. All images are at magnification, 400×.

To determine if the decreased numbers of neutrophils present in the lungs of ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury were a result of an inability to mobilize leukocytes from the bone marrow to the circulation, total and differential blood cell counts at 24 hours after injury were obtained. We observed a significant increase in the numbers of circulating neutrophils (5000 ± 555 cells/µl) in the blood of ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn compared with their wild-type counterparts (2900 ± 400 cells/µl).

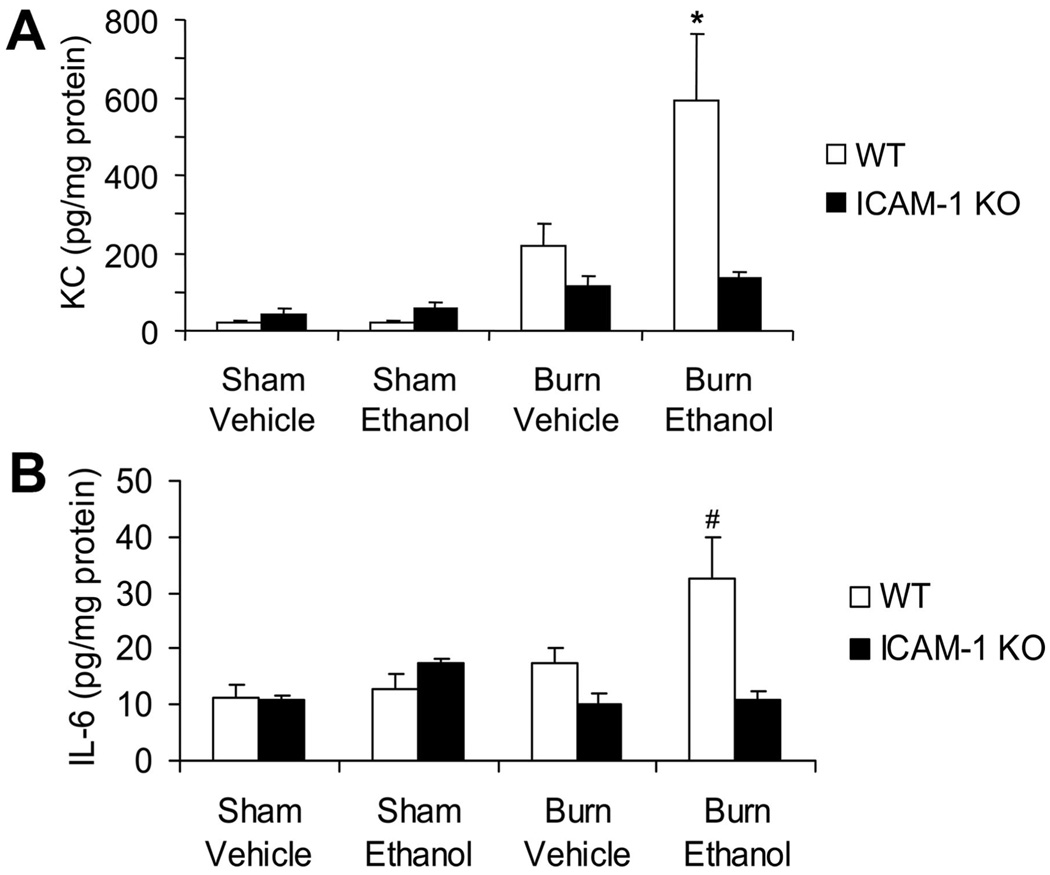

Decreased Proinflammatory Cytokines in ICAM-1 KO Mice

Next, we wanted to determine if the decreased neutrophil accumulation in the lungs of ethanol-exposed, burn-injured KO mice was simply due to the lack of ICAM-1 or if there was a decrease in neutrophil chemoattractants as well. As shown in Figure 4A, there was a significant increase in the amount of KC, an analog to human IL-8, present in the lungs of wild-type mice after the combined injury compared with mice receiving either injury alone (P < .01). Interestingly, although we were able to detect levels of KC in the lungs of mice given burn injury alone, they were not significantly different from sham levels. However, there was a 77% reduction in the levels of KC in ICAM-1 KO mice compared with their wild-type counterparts after ethanol exposure and burn injury (P < .01). There were no differences in the levels of KC between wild-type and ICAM-1 KO mice after burn injury alone. Levels of pulmonary KC in the ICAM-1 KO mice were not significantly different across treatment groups.

Figure 4.

Decreased pulmonary levels of proinflammatory mediators after ethanol exposure and burn injury in intercellular adhesion molecule-1 knockout (ICAM-1 KO) mice. Levels of KC (A) and interleukin (IL)-6 (B) in the lung were quantified by multiplex assay in total lung homogenates. Cytokine concentrations were normalized to total protein in the sample as determined by BioRad protein assay and presented as concentration ± SEM. *P < .01 compared with all other groups, #P < .05 compared with all groups but sham ethanol knockout. N = 7–12 animals per group. No significant differences were seen in monocyte inflammatory protein-2 production in the lung.

KC levels in the lung are upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines; however, no differences in TNF-α were observed in the lungs at 24 hours after injury. We did observe a 50% reduction in IL-1β levels in the lungs in ICAM-1 KO mice compared with wild-types after both burn and the combined injury (data not shown). In addition, we saw a significant upregulation of IL-6 in the lungs of wild-type mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury (32.4 ± 7.4 pg/mg protein) compared with mice receiving burn alone (17.3 ± 3 pg/mg protein; Figure 4B). Similar to KC, the levels of IL-6 observed in the lungs of mice receiving burn alone were not different from their sham counterparts. This upregulation of IL-6 was absent in the KO mice since these mice had similar levels to sham animals (10.8 ± 1.8 pg/mg protein; Figure 4B). Circulating levels of IL-6 were also measured. Similar to levels observed in the lungs, wild-type mice showed significantly increased amounts of IL-6 in their serum after ethanol exposure and burn injury compared with sham animals and animals subjected to burn alone (Table 1). The ICAM-1 KO mice had low levels of IL-6 in their circulation regardless of treatment group (Table 1). These data suggest that in addition to lacking ICAM-1, the KO mice also have a decreased inflammatory response to ethanol exposure and burn injury.

Table 1.

Circulating levels of IL-6 after ethanol exposure and burn injury*

| Sham Vehicle |

Sham Ethanol |

Burn Vehicle |

Burn Ethanol |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 0 ± 0 | 15.5 ± 15.5 | 70.4 ± 40.9 | 377.5 ± 113.1† |

| ICAM-1 KO | 10.6 ± 10.6 | 14.2 ± 14.2 | 77.8 ± 25.1 | 108.3 ± 41.5 |

n = 3–6 animals per group.

Levels of IL-6 (pg/ml) ± SEM.

P < 0.05 compared with all other groups by one-way ANOVA.

IL, interleukin; WT, wild-type; ICAM-1 KO, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 knockout.

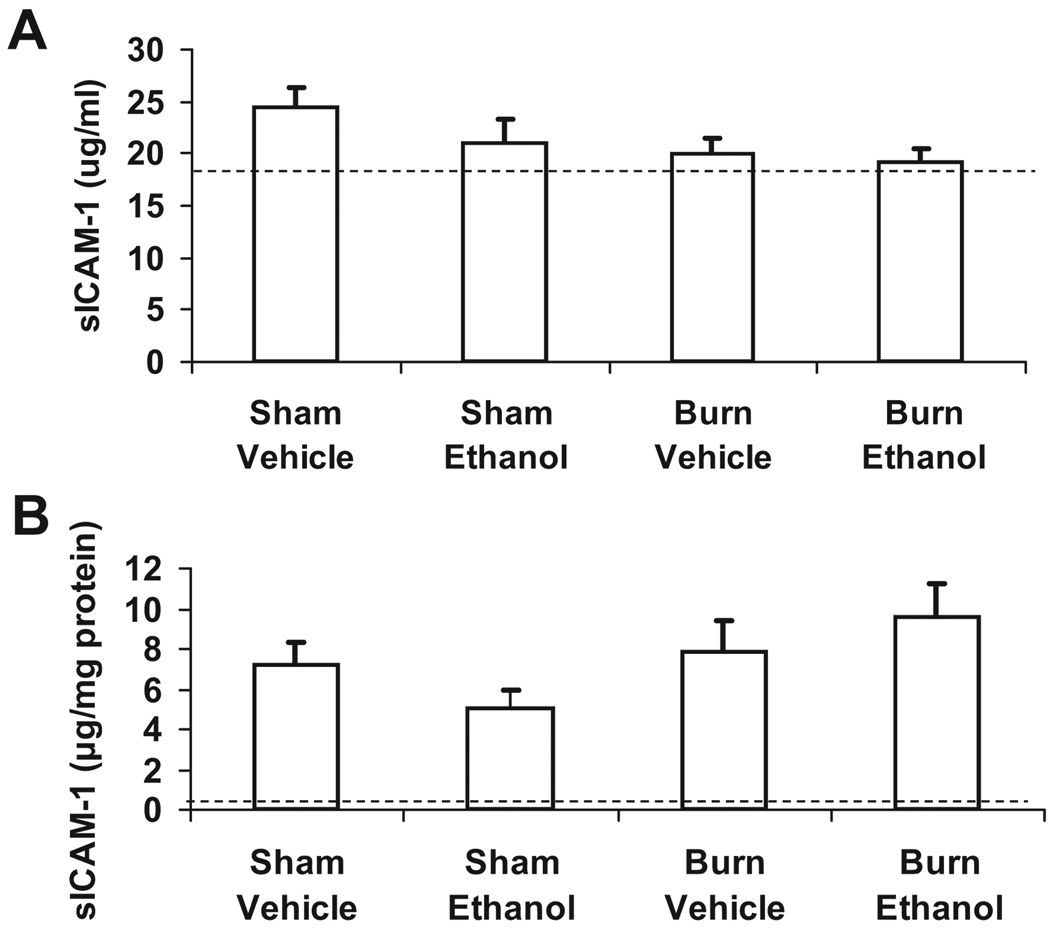

Comparable Levels of Soluble ICAM-1 After Ethanol Exposure and Burn Injury

We wished to determine if sICAM-1 was increased in our model of ethanol exposure and burn injury. We examined levels of sICAM-1 by ELISA in both serum and lung homogenates. Normal serum levels range from 10.3 to 13.8 µg/ml (manufacturer protocol), which is only slightly below the range of sICAM-1 that we observed in our wild-type mice, regardless of treatment group (Figure 5). Concentrations of sICAM-1 were lower in the lung homogenates (5–10 pg/mg protein), but again there were no differences observed among the 4 treatment groups. These data suggest that at least at 24 hours postinjury, sICAM-1 is not a reliable indicator of systemic or pulmonary inflammation in our model.

Figure 5.

No differences in soluble ICAM-1 in serum or lung after ethanol exposure and burn injury. Levels of soluble ICAM (sICAM)-1 in serum (A) and lung homogenates (B) were quantified by ELISA. Soluble ICAM-1 levels in the lung were normalized to total protein in the sample as determined by BioRad protein assay and presented as concentration ± SEM. Dashed line represents the level of sICAM-1 in the serum and lungs of ICAM-1 KO mice. N = 7–12 animals per group.

DISCUSSION

Because of recent advances in antibiotics and standard care practices, infection in the wound bed is no longer the major cause of morbidity and mortality in burn patients.33,34 Instead, the major postinjury complications result from sepsis and multiple organ failure,7 with lungs being one of the first organs to fail. In addition, chronic ethanol consumption was linked with increased risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. 35 Although the exact mechanism by which ethanol increases pulmonary dysfunction after burn injury remains to be elucidated, several possibilities include leakage of proinflammatory mediators and endotoxin from the gut to the lungs, the increased risk of contact with pathogens from both the circulation and the airway, and the delicate architecture of the lung itself. Animal models have shown that these proinflammatory factors released from the gut after burn or trauma-hemorrhage lead to neutrophil and endothelial cell activation, with upregulation of adhesion molecules,36 and acute lung injury.37

We demonstrated previously that ethanol exposure before burn injury results in increased pulmonary edema and neutrophil accumulation beginning as early as 2 hours after injury and continues last 48 hours.8 Histochemical analysis of lung sections at 24 hours postinjury showed increased leukocyte emigration into the lungs of mice given ethanol and burn injury compared with mice given burn alone. The increase in pulmonary inflammation in the wild-type animals after ethanol exposure and burn correlated with an increased vascular congestion severity score. This increase in vascular congestion may result in an inability of these animals to oxygenate and perfuse tissues appropriately and subsequent tissue injury. However, further measurements of tissue injury need to be performed to accurately assess the role of the combined insult in lung injury. The ICAM-1 KO mice showed mild vascular congestion in the lung across all treatment groups because of the presence of rounded erythrocytes and the occasional neutrophil in the capillaries. However, the vascular congestion was less pronounced in the KO animals even after ethanol exposure and burn injury pointing to this being an issue of the KO phenotype.

In previous studies, pulmonary levels of neutrophils and monocyte inflammatory protein-2, another neutrophil chemoattractant factor, were elevated at early time points after ethanol exposure and burn injury.8 However, levels of KC were not observed to be different in burn and ethanol-treated mice. Also, in these earlier studies, pulmonary edema (as measured by lung wet weight) was higher in mice given burn and ethanol, suggesting a possible increase in vascular leakiness.8 In this study, we observed a similar pattern of increased neutrophil infiltration in mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury (Figure 2), but, unlike the previous study, we saw significantly higher levels of KC at 24 hours after the combined injury (Figure 4A). This discrepancy may simply be due to the difference in strains of mice used (C57BL/6 vs B6D2F1) or that we used multiplex bead arrays in this study, which is a more sensitive assay. By using a rat model, Li et al9 also showed increased levels of neutrophil infiltration, neutrophil chemoattractants (CINC-1/CINC-3), and pulmonary edema after the combined injury compared with ethanol exposure or burn injury alone.

The study by Li et al9 also showed increased expression of ICAM-1 in the lungs of rats exposed to ethanol and burn injury. In this study, we expanded on this observation and examined the effect of ethanol exposure and burn injury on mice that are genetically deficient in ICAM-1. Not surprisingly, we observed decreased levels of neutrophils emigrating from the circulation into the lungs of the ICAM-1 KO mice after the combined injury (Figure 2). As mentioned earlier, a possible explanation for the decreased numbers of pulmonary neutrophils in the ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury could be a result of a genetic defect of these mice to mobilize innate immune cells from the bone marrow to the circulation. However, a previous study showed increased numbers of neutrophils in the circulation after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration in ICAM-1 KO mice.28 Consistent with the above study, we observed a significant increase in the numbers of circulating neutrophils in the blood of ICAM-1 KO mice after ethanol exposure and burn injury compared with their wild-type counterparts. Therefore, the KO mice do not have a defect in generation of neutrophils or mobilization, but because of the lack of the presence of membrane bound ICAM-1 and/or the decreased levels of chemoattractants, the neutrophils do not readily gain access to the lung interstitial tissues. The increase in circulating neutrophils may also have lead to the increase in vascular congestion observed in the lungs of these animals.

However, we also observed decreased proinflammatory cytokine production in both the serum and the lungs compared with wild-type mice. This is in contrast to an earlier study, which showed similar levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in the serum after high doses of LPS were given to ICAM-1 deficient mice.28 The ICAM-1 KO mice in this study had fewer infiltrating neutrophils in the liver and were resistant to endotoxic shock.28 Therefore, one may hypothesize that part of the proinflammatory cytokine production observed in the lung after ethanol exposure and burn injury may be dependent on the emigration of neutrophils into the tissue. Another possibility could be that ICAM-1 is important for macrophage activation after ethanol exposure and burn injury. We have shown increased levels of IL-6 in splenocyte culture supernatants that were dependent on the presence of macrophages.3 The observed decreased pulmonary IL-6 in ICAM-1 KO mice after the combined injury could be a result of decreased activation of alveolar macrophages or that the cytokines found in the lung are produced by infiltrating macrophages instead of the resident cells. Interestingly, the study described earlier by Xu et al28 showed that if the ICAM-1 KO mice were given d-galactosamine and staphylococcal enterotoxin B, they had significantly lower circulating levels of IL-1β and TNF-α and were protected from lethality, suggesting that the response in ICAM-1KO mice may be dependent on the model used.

KC levels in the lung are upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α38; however, no differences in TNF-α were observed in the lungs at 24 hours after injury. This is expected because serum levels of TNF-α are known to peak at 90 minutes after burn in the circulation.39,40 IL-1β was shown to upregulate the expression of neutrophil chemoattractants through NF-κB.41 Blocking the receptor for IL-1 resulted in decreased LPS-induced production of CINC-1 and monocyte inflammatory protein-2 in lung, plasma, and liver.42 Because the ICAM-1 KO mice produce lower levels of IL-1β, it is expected that KC levels would also be decreased in the lung. In addition, it was shown that cross-linking of ICAM-1 induced the production of the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8 in human endothelial cells.43 Therefore, it may be possible that the lack of ICAM-1 signaling results in decreased levels of KC in our KO mice. Another possibility could also be that the infiltrating neutrophils are responsible for the increased production of IL-6 and KC. Determination of the actual cells responsible for the proinflammatory cytokine production in the lung after ethanol exposure and burn injury is an ongoing investigation by our laboratory. IL-6 was also shown to be involved in neutrophil chemotaxis to the lungs during pneumonia, although through a different mechanism involving STAT1 and STAT3.44 It stands to reason that the lack of IL-6 in the lungs and circulation may also have affected the migration of neutrophils into lung interstitium.

In addition to its membrane-bound form, ICAM-1 can be cleaved and released as a soluble mediator. ICAM-1 is expressed constitutively in the lungs on alveolar epithelial cells,45 and the proteolytically cleaved soluble form can be found in the bronchoalveolar lavage samples of normal mice,46 and increased sICAM-1 was observed in patients after burn and acute lung injury.19,20,47 In our model, we did not observe any differences in sICAM-1 levels between groups regardless of the tissues examined. In fact, the levels detected were comparable with basal levels of this adhesion molecule in lung and serum. These data suggest that either the 15% TBSA injury is not sufficient to induce high levels of sICAM-1 or perhaps 24 hours is not the correct time point to detect sICAM-1 in the serum and lungs. The second hypothesis is consistent with other studies performed in a mouse model of hypoxia-induced lung injury, which showed levels of sICAM-1 similar to uninjured mice on days 1 and 2 postinjury and increased sICAM-1 after 3 to 4 days postinjury in the lung.21

In summary, we have shown that mice genetically deficient in ICAM-1 display a significant reduction in pulmonary neutrophil infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine production after ethanol exposure and burn injury. These data demonstrate that ICAM-1 is an integral part of the excessive pulmonary inflammation observed after ethanol exposure and burn injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marykay Olson for help with histology, Dr. Henry Brown for thoughtful discussions about lung pathology, and Dr. Shegufta Mahbub and Cory Deburghgraeve for critical review of the manuscript.

Supported by NIH grants R01AA012034 (E.J.K.), R01AA012034-S1 (E.J.K.), T32AA013527 (E.J.K.), F32 AA018068 (M.D.B.), an Illinois Excellence in Academic Medicine grant, The Margaret A. Baima Endowment Fund for Alcohol Research, and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall JC. SIRS and MODS: what is their relevance to the science and practice of intensive care? Shock. 2000;14:586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore FA, Moore EE. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of postinjury multiple organ failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:257–277. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird MD, Kovacs EJ. Organ-specific inflammation following acute ethanol and burn injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:607–613. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howland J, Hingson R. Alcohol as a risk factor for injuries or death due to fires and burns: review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 1987;102:475–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowal-Vern A, Walenga JM, Hoppensteadt D, et al. Interleukin-2 and interleukin-6 in relation to burn wound size in the acute phase of thermal injury. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, et al. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J Trauma. 1995;38:931–934. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomkin JS. Neutrophil disorders in burn injury: complement, cytokines, and organ injury. J Trauma. 1990;30(Suppl 12):S80–S85. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199012001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel PJ, Faunce DE, Gregory MS, et al. Elevation in pulmonary neutrophils and prolonged production of pulmonary macrophage inflammatory protein-2 after burn injury with prior alcohol exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:1229–1237. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Kovacs EJ, Schwacha MG, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication increases interleukin-18-mediated neutrophil infiltration and lung inflammation following burn injury in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1193–L1201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00408.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansbrough JF, Wikström T, Braide M, et al. Neutrophil activation and tissue neutrophil sequestration in a rat model of thermal injury. J Surg Res. 1996;61:17–22. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravage ZB, Gomez HF, Czermak BJ, et al. Mediators of microvascular injury in dermal burn wounds. Inflammation. 1998;22:619–629. doi: 10.1023/a:1022366514847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baskaran H, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Dynamics of tissue neutrophil sequestration after cutaneous burns in rats. J Surg Res. 2000;93:88–96. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demling RH, LaLonde C, Liu YP, et al. The lung inflammatory response to thermal injury: relationship between physiologic and histologic changes. Surgery. 1989;106:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albelda SM, Smith CW, Ward PA. Adhesion molecules and inflammatory injury. FASEB J. 1994;8:504–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeed RW, Varma S, Peng T, et al. Ethanol blocks leukocyte recruitment and endothelial cell activation in vivo and in vitro. J Immunol. 2004;173:6376–6383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams DH, Nash GB. Disturbance of leucocyte circulation and adhesion to the endothelium as factors in circulatory pathology. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:17–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roebuck KA, Finnegan A. Regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (CD54) gene expression. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:876–888. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin RB, Zhu PF, Wang ZG, et al. Changes of pulmonary intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and CD11b/CD18 in peripheral polymorphonuclear neutrophils and their significance at the early stage of burns. Chin J Traumatol. 2003;6:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed Sel-D, el-Shahat AS, Saad SO. Assessment of certain neutrophil receptors, opsonophagocytosis and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) following thermal injury. Burns. 1999;25:395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calfee CS, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, et al. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:248–257. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendez MP, Morris SB, Wilcoxen S, et al. Shedding of soluble ICAM-1 into the alveolar space in murine models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L962–L970. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00352.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildebrand F, Pape HC, Harwood P, et al. Role of adhesion molecule ICAM in the pathogenesis of polymicrobial sepsis. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2005;56:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato N, Suzuki Y, Nishio K, et al. Roles of ICAM-1 for abnormal leukocyte recruitment in the microcirculation of bleomycin-induced fibrotic lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1681–1688. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9907104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frossard JL, Saluja A, Bhagat L, et al. The role of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and neutrophils in acute pancreatitis and pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:694–701. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colantoni A, Duffner LA, De Maria N, et al. Dose-dependent effect of ethanol on hepatic oxidative stress and interleukin-6 production after burn injury in the mouse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1443–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Glucocorticoids protect against suppression of T cell responses in a murine model of acute ethanol exposure and thermal injury by regulating IL-6. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:724–732. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.6.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messingham KA, Fontanilla CV, Colantoni A, et al. Cellular immunity after ethanol exposure and burn injury: dose and time dependence. Alcohol. 2000;22:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H, Gonzalo JA, St Pierre Y, et al. Leukocytosis and resistance to septic shock in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:95–109. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on cellular immune responses in a murine model of thermal injury. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:733–740. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faunce DE, Llanas JN, Patel PJ, et al. Neutrophil chemokine production in the skin following scald injury. Burns. 1999;25:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomellini V, Faunce DE, Gomez CR, et al. An age-associated increase in pulmonary inflammation after burn injury is abrogated by CXCR2 inhibition. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1493–1501. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tompkins RG, Burke JF. Burn therapy 1985: acute management. Intensive Care Med. 1986;12:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00261738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tompkins RG, Remensnyder JP, Burke JF, et al. Significant reductions in mortality for children with burn injuries through the use of prompt eschar excision. Ann Surg. 1988;208:577–585. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198811000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, et al. The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. JAMA. 1996;275:50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu DZ, Lu Q, Adams CA, et al. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced up-regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules is blunted by mesenteric lymph duct ligation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:760–765. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114815.88622.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magnotti LJ, Deitch EA. Burns, bacterial translocation, gut barrier function, and failure. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:383–391. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000176878.79267.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodman RB, Pugin J, Lee JS, et al. Cytokine-mediated inflammation in acute lung injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plackett TP, Colantoni A, Heinrich SA, et al. The early acute phase response after burn injury in mice. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:167–172. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013E31802CB84F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinrich SA, Messingham KA, Gregory MS, et al. Elevated monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 levels following thermal injury precede monocyte recruitment to the wound site and are controlled, in part, by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11:110–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sica A, Matsushima K, Van Damme J, et al. IL-1 transcriptionally activates the neutrophil chemotactic factor/IL-8 gene in endothelial cells. Immunology. 1990;69:548–553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calkins CM, Bensard DD, Shames BD, et al. IL-1 regulates in vivo C-X-C chemokine induction and neutrophil sequestration following endotoxemia. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sano H, Nakagawa N, Chiba R, et al. Cross-linking of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 induces interleukin-8 and RANTES production through the activation of MAP kinases in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:694–698. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones MR, Quinton LJ, Simms BT, et al. Roles of interleukin-6 in activation of STAT proteins and recruitment of neutrophils during Escherichia coli pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:360–369. doi: 10.1086/499312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Stolpe A, van der Saag PT. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Mol Med. 1996;74:13–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang BH, Crapo JD, Wegner CD, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on the alveolar epithelium and its modification by hyperoxia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;9:350–355. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakae H, Endo S, Tamada Y, et al. Bound and soluble adhesion molecule and cytokine levels in patients with severe burns. Burns. 2000;26:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]