Abstract

We investigated ethnic/religious mortality differentials in Bulgaria during the 1990s. The analyses employed a unique longitudinal data set covering the entire population of Bulgaria from the census of 1992 until 1998. The mortality of Roma is very high compared to all other ethnic/religious groups. The excess applies to nearly every cause of death examined and is not entirely explained by the adverse location of Roma on social and economic variables. For young men, Muslim mortality is substantially lower than that of non-Muslims when socioeconomic differences are controlled. An analysis of causes of death suggests that lower consumption of alcohol may contribute to this ‘Muslim paradox’. For older Muslim women, a significant mortality disadvantage remains after controls are imposed. Suicide mortality is lower for Muslims than for Christian groups of the same ethnicity. Consistent with deteriorating economic conditions over the study period, mortality was rising, particularly for women.

Keywords: Muslims, Christians, Turks, Pomaks, Roma, mortality, cause of death, life style, socioeconomic determinants, Bulgaria

1 Introduction

Ethnic and religious minority groups in Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries are understudied, despite their century-long presence and their increasing relevance for shaping demographic processes in the region. Specifically, limited knowledge exists about their health characteristics and mortality experience and how these compare with patterns and trends observed for the majority populations in these countries. In the analysis reported here we examined the health conditions of ethnic and religious groups in Bulgaria during the period of economic and social restructuring in the 1990s. Using a unique longitudinal micro dataset covering the entire population of Bulgaria during 1992–98, the aim of our analysis was to document mortality patterns during this period, providing the first reliable life table measures and cause-specific mortality indicators according to ethnicity and religion.

During the past two decades, debates about the sources and causes of the observed health deterioration in most Eastern European countries including Bulgaria, have been dominated by two main—but not mutually exclusive—explanatory approaches. Economically-oriented interpretations of mortality variation cite socioeconomic deprivation, limited access to health care, or worsening living conditions as primary causes for the observed mortality increase during the 1990s in Central and Eastern Europe (Delcheva et al. 1997; Mackenbach et al. 1999; Davis 2000). The economic setbacks in Bulgaria during this period provide an outstanding opportunity to examine mortality conditions under material adversity. Real income per head in Bulgaria fell from an index of 100 in 1989 to 61.5 in 1992 and further to 30.8 in 1998 (Gantcheva and Kolev 2001). Household budget surveys in 1992 and 1998 showed large declines in consumption per capita of fruits, vegetables, meat, and milk products (Gantcheva and Kolev 2001). The severe economic crisis during 1996–97 was characterized by a decline in GDP of 18 per cent and an annual inflation rate of 579 per cent. Poverty, as defined by the World Bank, escalated to 36 per cent of the population during this period (World Bank 2002, p. IX). Many social institutions, on which particularly economically disadvantaged ethnic minority groups such as Roma were relying to meet basic needs, collapsed after 1989. The result was a growing gap in wellbeing between the minorities and mainstream society in Bulgaria. During the period of investigation poverty was dramatically concentrated among certain population groups. Ethnic minorities comprised over 60 per cent of the poor population in the country, with Roma being ten times more likely to be poor and Turks four times more likely to be poor than ethnic Bulgarians (World Bank 2002, p. XI).

The disadvantaged status of ethnic and religious minorities in Bulgaria was not a new phenomenon. They had been secluded in a cycle of poverty, social and economic discrimination and exclusion, restricted education, poor access to health care, and neglect throughout the 20th century (Courbage 1992; Pickles 2001; UNDP 2004; Rechel 2008). Their marginalized status is clearly reflected in educational stratification. In 1992 among the non-institutionalized population, 72 per cent of adult Muslim men aged 25–90 in Bulgaria had completed fewer than 9 years of schooling, compared to 39 per cent of Bulgarian Christians. Comparable figures for women were 83 per cent and 42 per cent respectively (authors’ calculations based on the 1992 population census). After 1989, the political status of minority groups changed substantially, but the ambiguous socioeconomic reforms combined with pre-existing developmental conditions in the country pushed these groups to the margin of society, and, into a sharp impoverishment. In view of the non-linear relation between mortality and income per head or economic development more generally (Preston 1975), we thought it likely that the deteriorating economic circumstances would have a particularly severe impact on the most socially and economically disadvantaged ethnic and religious minority populations such as Roma, Turks, and Bulgarian Muslims (Pomaks).

In contrast to economically-oriented interpretations, the behavioural literature stresses the role of unhealthy life styles in Eastern Europe as a leading explanation of its unfavourable mortality levels and trends relative to Western Europe (Cockerham 1997; Laaksonen et al. 2001; McKee and Shkolnikov 2001; McKee et al. 2001; Shkolnikov et al. 2002; Leon et al. 2007). Among the life-style factors seen as key factors for the high mortality levels in the region are excessive alcohol consumption and the very poor quality of home-made alcohol (Szucs et al. 2005), a diet based on high intakes of animal fats and low consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, and the high prevalence of cigarette smoking (Bobak and Marmot 1996a, 1999; Cockerham 2007; Cockerham et al. 2004; Laaksonen et al. 2001). Poor personal life styles are not found in all segments of the society in Bulgaria. For instance, a 1997 Bulgarian national survey found that Muslim men were only 40 to 45 per cent as likely to consume alcohol or to drink heavily as Orthodox Christians (Balabanova and Mckee 1999). This low level of alcohol consumption among Muslims appears to be a general phenomenon (Cockerham et al. 2004). Thus, religiously mediated healthy life styles and stronger social networks observed specifically among Muslims may have enabled them to better withstand the greater economic insecurity of this period. If so, we expected these differences to be reflected in comparative mortality levels.

In summary, the analysis we present lies at the intersection of three important social phenomena observed in Bulgaria and Eastern Europe in general: the strong presence of ethnic and religious minority groups (specifically Muslim populations) about whose health conditions very little knowledge exists; worsening economic circumstances during the period of economic restructuring in the 1990s;, and very high and deteriorating mortality in Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries compared with Western Europe during the 1990s period of investigation (Bobak and Marmot 1996b; Laaksonen et al. 2001; Carlson 2004). By integrating these three phenomena, our analysis helped to identify reasons for the very high and rising mortality in Bulgaria and to illuminate the health status of large ethnic and religious minority populations. More generally, our analysis bore upon the relative explanatory power of economically-oriented and behavioural approaches to the study of adult health and mortality.

2 Description of data and analytic scheme

2.1 Data

The analyses utilized a unique longitudinal data set that followed the entire population of Bulgaria from the census on December 5th, 1992 to the end of 1998 by linking individuals enumerated in the 1992 census to subsequent death records. The linkage was performed by using a personal identification number uniquely assigned to each Bulgarian citizen and permanent resident and that was included on both the census and the death records. Approximately 93 per cent of all death certificates from the study period were linked to the census records of the individuals known to have died during this period. The linkage rate in this data set is higher than in mortality studies using records of the U.S. Social Security Administration and comparable to that of studies using the National Death Index (Cowper et al. 2002, p. 114).

The dataset contains a broad range of individual demographic and socioeconomic characteristics measured at census, including ethnicity, religion, mother tongue, completed educational attainment, marital status, detailed occupation and industry of employment, place of residence, and various characteristics of the dwelling occupied by the enumerated individual. The availability of cause-of-death records was a valuable asset in sorting out the different mechanisms that may have differentiated the health circumstances of different ethnic and religious groups in Bulgaria.

The most problematic and challenging aspect involved in the analyses of mortality by ethnicity and religious groups in Bulgaria was the assignment of individuals to a specific group. Our scheme for making this assignment is described in the Appendix. It is based on responses to census questions on ethnicity, religion, and mother tongue. We note in the Appendix that identification as Roma appeared to be the least reliable of the groups considered.

2.2 Analytical Scheme

All analyses were restricted to the non-institutionalized adult population aged 20 and over, and were conducted separately for men and women. One advantage of focusing on adult mortality is that we avoided potential problems in measuring mortality of children in the census-based dataset. Since our dataset included only individuals alive on December 5th 1992—the census day—infant mortality rates could not have been accurately estimated because they require observation from birth.

We first document mortality patterns in Bulgaria during the period 1993–98 and provide the first reliable life tables and other mortality measures by religion and ethnic groups. In particular, we calculated life tables for the following 2-year periods: 1993–94, 1995–96, and 1997–98. In order to provide reliable estimates for the highest ages, we estimated Gompertz models by sex and ethnic/religious groups for the age range 65–95 years. Kohler and Kohler have previously shown that the Gompertz model provides a very good fit to mortality data in Bulgaria, including data for the old and oldest-old. In our models, we also included dummies for the respective 2-year periods and allowed the level-parameter, but not the slope-parameter, to vary by period. For Bulgarian Christians, Gompertz estimates were used above age 85 for men and above age 90 for women. For Turks and Pomaks the starting age was 80 for men and 85 for women. For Roma, the starting ages were 70 for men and 75 for women. We then calculated period life tables by ethnicity and religious membership based on standard demographic methods (Preston et al. 2001).

To analyse mortality differentials between Muslims and non-Muslims, we estimated non-parametric piecewise-constant hazard models in which the death rate was modelled as a function of age and a series of covariates measured at the individual level.

The post-communist period of economic transition in Bulgaria was characterized by substantial out-migration. The emigration process was particularly pronounced among the Turkish minority and started before the beginning of the transition period. In the summer of 1989, over 360,000 Turks and Roma left Bulgaria for Turkey (Pickles 2001), but in the following years strong return migration was observed (Kaltchev 2005). The region most affected by out-migration in the summer of 1989 was Kardshali, a region situated in the south of Bulgaria along the border with Turkey. Kardshali was also the region with the lowest per centage of linked deaths in our dataset (89 per cent). Other ethnically diverse regions or regions also situated along the border with Turkey had higher percentages of linked deaths. One possible explanation for the low linkage rate in Kardshali is that these death records were for individuals who had not been enumerated in the 1992 population Census because they had left Bulgaria before the census (e.g., in the summer of 1989) and later returned. After 1993, migration had an economic character and was concentrated among the better-educated young people. A survey from 2001 showed that among all the ethnic groups, Roma had the lowest migration intensity (Kaltchev 2005).

To investigate whether migration distortions affected our estimates, we estimated piecewise-constant hazard models in which we interacted the ethnicity variable with a linear time variable. It was our hypothesis that any migration distortions would have grown as the period of observation increased, whereas the ethnicity variables themselves would not have shown a time trend. Specific analyses (not reported here) showed that none of the ethnicity–time-trend interaction variables were statistically significant.

2.3 Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the ethnic/religious groups included in the analysis presented below. All socioeconomic characteristics refer to characteristics measured at census. As a result, we could not assess how changes in demographic and socioeconomic indicators were related to mortality outcomes during the entire period of observation.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by ethnic/religious group derived from the 1992 census and vital statistics 1993–98, Bulgaria

| Bulgarian Christians | Turks | Pomaks | Christian Roma | Muslim Roma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men age 30–60 years | |||||

| Total population (January 1st, 1993) | 1,667,125 | 184,962 | 24,622 | 37,791 | 24,570 |

| Mean age (January 1st, 1993) | 42.51 (9.48) | 40.59 (9.35) | 40.74 (9.40) | 38.66 (8.72) | 38.96 (8.88) |

| Total number of deaths (1993–98) | 81,470 | 7,581 | 981 | 1,956 | 1,218 |

| Mean age at death (1993–98) | 53.24 (7.98) | 52.3 (8.59) | 52.39 (8.58) | 51.12 (8.95) | 51.42 (8.88) |

| Per cent married | 80.94 | 89.04 | 89.58 | 88.96 | 89.89 |

| Years of education (per cent) | |||||

| 0–8 | 28.05 | 68.59 | 57.79 | 87.76 | 90.64 |

| 9–12 | 53.45 | 29.46 | 38.13 | 11.43 | 9.09 |

| 13–15 | 3.52 | 1.08 | 2.00 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| 16+ | 14.99 | 0.87 | 2.08 | 0.55 | 0.13 |

| Place of residence (per cent) | |||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 35.73 | 8.00 | 0.66 | 16.91 | 8.8 |

| Small town (<100,000 population) | 39.96 | 23.52 | 16.65 | 42.27 | 33.09 |

| Village | 24.31 | 68.48 | 82.69 | 40.82 | 58.11 |

| Standard of accommodation | |||||

| Mean of household index | 4.67 (1.10) | 3.24 (1.04) | 3.61 (0.91) | 2.85 (1.12) | 2.78 (0.92) |

| Square meters/HH member | 13.95 (9.25) | 12.23 (8.32) | 12.91 (8.44) | 8.39 (6.55) | 8.95 (6.59) |

| Men age 60–90 years | |||||

| Total population (January 1st, 1993) | 959,718 | 65,065 | 8,917 | 6,793 | 5,148 |

| Mean age (January 1st, 1993) | 66.93 (7.21) | 65.79 (6.61) | 65.87 (7.00) | 64.29 (5.76) | 64.53 (5.75) |

| Total number of deaths (1993–98) | 240,599 | 15,566 | 1,957 | 1,962 | 1,453 |

| Mean age at death (1993–98) | 74.85 (8.17) | 73.14 (7.70) | 73.72 (8.32) | 69.98 (7.03) | 70.46 (6.92) |

| Per cent married | 82.4 | 83.84 | 86.26 | 79.02 | 82.26 |

| Years of education (per cent) | |||||

| 0–8 | 64.76 | 95.86 | 97.38 | 96.7 | 99.03 |

| 9–12 | 22.21 | 3.02 | 1.94 | 2.53 | 0.7 |

| 13–15 | 2.82 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.08 |

| 16+ | 10.21 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.19 |

| Place of residence (per cent) | |||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 27.01 | 4.35 | 0.31 | 13.91 | 6.72 |

| Small town(<100,000 population) | 30.04 | 16.86 | 12.82 | 41.25 | 29.68 |

| Village | 42.96 | 78.78 | 86.87 | 44.84 | 63.6 |

| Standard of accommodation | |||||

| Mean of household index | 4.16 (1.22) | 2.99 (0.92) | 3.34 (0.91) | 2.73 (0.99) | 2.71 (0.83) |

| Square meters/HH member | 19.12 (12.11) | 15.79 (11.54) | 14.62 (9.82) | 10.89 (9.04) | 11.07 (8.45) |

| Women age 30–60 years | |||||

| Total population (January 1st, 1993) | 1,703,476 | 185,472 | 24,456 | 38,231 | 25,009 |

| Mean age (January 1st, 1993) | 42.76 (9.53) | 40.89 (9.35) | 41.33 (9.47) | 38.99 (8.88) | 39.29 (8.97) |

| Total number of deaths (1993–98) | 33,281 | 3,629 | 420 | 1,061 | 668 |

| Mean age at death (1993–98) | 53.89 (8.10) | 53.42 (8.40) | 52.99 (8.47) | 52.71 (8.57) | 52.5 (8.80) |

| Per cent married | 81.86 | 87.83 | 88.22 | 82.94 | 83.69 |

| Years of education (per cent) | |||||

| 0–8 | 26.39 | 81.84 | 75.28 | 93.3 | 96.65 |

| 9–12 | 50.66 | 16.33 | 21.21 | 6.16 | 3.16 |

| 13–15 | 8.34 | 1.37 | 2.64 | 0.21 | 0.09 |

| 16+ | 14.61 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| Place of residence (per cent) | |||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 37.57 | 7.77 | 0.54 | 16.89 | 8.84 |

| Small town (<100,000 population) | 40.11 | 23.85 | 15.94 | 42.86 | 33.61 |

| Village | 22.32 | 68.37 | 83.52 | 40.25 | 57.55 |

| Standard of accommodation | |||||

| Mean of household index | 4.47 (1.06) | 3.24 (1.04) | 3.59 (0.91) | 2.87 (1.12) | 2.79 (0.91) |

| Square meters/HH member | 13.93 (8.82) | 12.29 (8.19) | 13.13 (8.47) | 8.4 (6.51) | 9.08 (6.58) |

| Women age 60–90 years | |||||

| Total population (January 1st, 1993) | 1,144,499 | 71,089 | 10,840 | 8,424 | 6,117 |

| Mean age (January 1st, 1993) | 67.64 (7.57) | 66.33 (7.15) | 66.64 (7.57) | 64.83 (6.16) | 65.19 (6.41) |

| Total number of deaths (1993–98) | 222,718 | 13,024 | 1,716 | 1,908 | 1,379 |

| Mean age at death (1993–98) | 77.69 (8.02) | 75.59 (8.24) | 77.14 (8.57) | 72.07 (7.59) | 72.88 (7.75) |

| Per cent married | 57.83 | 62.18 | 60.38 | 52.64 | 52.49 |

| Years of education (per cent) | |||||

| 0–8 | 73.41 | 98.93 | 99.29 | 98.3 | 99.66 |

| 9–12 | 19.39 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 1.21 | 0.25 |

| 13–15 | 3.41 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| 16+ | 3.79 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.08 |

| Place of residence (per cent) | |||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 26.97 | 4.47 | 0.19 | 14.33 | 7.42 |

| Small town (<100,000 population) | 29.45 | 17.36 | 12.88 | 40.62 | 29.61 |

| Village | 43.59 | 78.17 | 86.93 | 45.05 | 62.97 |

| Standard of accommodation | |||||

| Mean of household index | 4.11 (1.24) | 2.97 (0.91) | 3.30 (0.91) | 2.71 (0.97) | 2.67 (0.81) |

| Square meters/HH member | 20.62 (13.91) | 19.09 (12.12) | 15.69 (12.10) | 10.91 (9.52) | 11.64 (9.31) |

Note: Standard deviation in parentheses.

Source: Census of Bulgaria 1992 and vital statistics for the period 1993–98.

On average, the Bulgarian Christian population is older, better educated, and wealthier (as measured by the household index and square meters of living space available per household member) than all other ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria. About 18 per cent of Bulgarian Christian men and 23 per cent of women aged 30 to 60 have completed 13 or more years of education. In contrast, less than 1 per cent of Roma men and women have 13 or more years of education. These numbers are also strikingly low for the Turkish and Pomak groups—less than 2 per cent of Turkish men and women aged 30 to 60 have completed 13 or more years of education, and only about 3.5–4 per cent of Pomak men and women. Educational attainment is lower among the older population. Above age 60, 65 per cent of Bulgarian Christian men and 73 per cent of women have completed 8 or fewer years of education. Among the remaining ethnic/religious groups more than 90 per cent of elderly men and women fall into this category. Bulgarian Christians are also more likely to live in big cities than their counterparts from other ethnic/religious groups. Marriage is more or less universal across all ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria. More than 80 per cent of the census population below age 60 in all ethnic/religious groups are married. Among women above age 60 the fraction of married individuals varies from 53 per cent among Christian Roma to 62 per cent among Turkish women.

3 Life-table parameters for ethnic and religious groups in Bulgaria during the 1990s

To draw an initial picture of the characteristic mortality profiles of Muslim and non-Muslim populations in Bulgaria during the 1990s, we first discuss period life-table parameters estimated for these groups. We computed life tables conditional on survival to age 20 for the years 1993–94, 1995–96, and 1997–98. The boxplot-like Figure 1 summarizes the distribution of age at death (1d↓x) for men and women based on these life tables. The life-table mean age at death for the population aged 20 and over, calculated as life expectancy at age 20 (e↓20) plus 20, is shown by the little dots within the boxes. The length of the boxes shows the inter-quartile range in the age at death, and the bottom and upper lines correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles of the age-at-death distribution. The bottom and top whiskers denote the 10th and 90th percentiles respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age at death conditional on survival to age 20 by sex and period for different Muslim and non-Muslim population groups.

Source: As for Table 1.

Figure 1 reveals that there is substantial variation in mortality between the ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria that is highly systematic across sex and period. Muslim and Christian Roma men and women experience the highest mortality and lowest mean age at death among all groups and years. For example, the mean age at death of Christian Roma men in the period 1993–94 is 5.6 years below that estimated for Bulgarian Christian men, a difference that decreases to 5.07 years in the latest period included. Similarly, the life expectancy e20 of Christian Roma women is more than 6 years lower than that of their Bulgarian Christian counterparts.

In contrast to the very distinctive pattern of the Roma population, the distributions of ages at death of the other groups are very similar to one another. Among men, the Pomaks have the highest mean age at death, one that exceeds that of Bulgarian Christian men by 0.34 years, 0.75 years, and 0.56 years as time advances. In general, Pomak men retain a slight relative and absolute mortality advantage at all ages compared to Bulgarian Christian men. Turkish men have a mean age at death that is 0.37 years lower than Bulgarian Christian men in 1993–94, and this difference slightly increases in the following period to 0.51 years. In contrast, Turkish men have a slight absolute and relative mortality advantage at younger ages as revealed by the 10th percentiles of the distribution of age at death shown on the upper graphs in Figure 1. In particular, the 10th percentile for Turkish men is 0.83 years higher than that for Bulgarian Christian men in 1993–94, a difference that decreases in the following two periods to 0.22 and 0.34 years respectively.

For women, the observed patterns are somewhat different. The only ethnic/religious group with lower mortality than that of Bulgarian Christian women is the group of Pomak women, although their mortality advantage declines over time. All other ethnic/religious groups experience higher levels of mortality than Bulgarian Christian women.

Figure 1 reveals little variation in the inter-quartile ranges of the distribution of age at death among the ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria. This indicates that the mortality differences are systematic across ages and no mortality cross-over occurs among the ethic/religious groups, at least in terms of the age distribution of deaths.

4 Mortality differentials among Muslims and non-Muslims in Bulgaria

In this section, we present the results of our investigations of mortality differentials between the Muslim and non-Muslim populations at different stages of the life course, and estimates of the extent to which demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of these populations contributed to the observed mortality differences. We focused on mortality above age 30, which is approximately the age at which men and women begin to develop the chronic diseases that are the principal causes of adult morbidity and mortality.

Table 2 shows relative risks of dying by ethnic/religious group derived from four piecewise-constant hazard models that control for various individual demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. In the baseline Model 1, we controlled only for age and calendar year. In the next Model 2, we introduced educational attainment as an additional control variable. Model 3 added indicators for place of residence (i.e., villages, small towns, and cities with a population above 100,000 inhabitants), marital status, square metres of living space available to each household member, and dummy variables for the quartiles of a household wealth index to which a person’s household belongs. We explain how the household index was computed in Section 5, when we discuss the association of various socioeconomic characteristics with the mortality of ethnic/religious groups. In Model 4, we added a control variable for region of residence at census since regions in Bulgaria differ considerably in economic development, infrastructure, and population composition (see for instance United Nations Development Programme 1996). The four models were estimated separately by sex and two age ranges—30–60 and 60–90 years. In all models, the baseline hazard of mortality was assumed to be constant within 2-year age intervals. The reference category in all models was the respective Bulgarian Christian population. We discuss the results separately for each sex and age group.

Table 2.

Relative risk of dying by ethnic/religious group, derived from piecewise-constant proportional hazard models, hazard models, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Bulgarian Christians | Turks | Pomaks | Christian Roma | Muslim Roma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men age 30–60 years | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.951 | 1.584** | 1.454** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 0.820** | 0.791** | 1.240** | 1.127** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 0.811** | 0.848** | 1.122** | 1.051+ |

| Model 4 | 1 | 0.844** | 0.932* | 1.122** | 1.040 |

| Men age 60–90 years | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.088** | 0.955* | 1.681** | 1.591** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.020* | 0.896** | 1.569** | 1.479** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 0.987 | 0.889** | 1.409** | 1.359** |

| Model 4 | 1 | 0.988 | 0.946* | 1.406** | 1.330** |

| Women age 30–60 years | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.201** | 0.986 | 2.101** | 1.975** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.010 | 0.834** | 1.730** | 1.617** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 0.977 | 0.851** | 1.499** | 1.436** |

| Model 4 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.964 | 1.500** | 1.410** |

| Women 60–90 years | |||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.108** | 0.859** | 1.871** | 1.744** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.061** | 0.824** | 1.787** | 1.662** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.019* | 0.798** | 1.630** | 1.525** |

| Model 4 | 1 | 1.033** | 0.953+ | 1.619** | 1.485** |

Notes: p values:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p <0.01.

Model 1 -- controls for age and calendar year.

Model 2 -- controls for age, calendar year and years of education.

Model 3 -- controls for age, calendar year, years of education, place of residence, marital status, square meters per HH member, HH index

Model 4 -- controls for age, calendar year, years of education, place of residence, marital status, square meters per HH member, HH index and region of residence at census.

Source: As for Table 1

Men 30–60 years old

In the baseline model 1, Turkish and Pomak men do not experience risks of death significantly different from those of the reference category of Bulgarian Christian men, despite their poorer socioeconomic circumstances (see Table 1). Controlling for education in Model 2, the relative risks of dying are substantially reduced for both Turkish and Pomak men: younger Turkish men have an 18-per-cent and Pomak men a 21 per cent lower relative risk of dying than Bulgarian Christians once education is controlled. The magnitude and significance level of the estimated relative risk of death for Turkish men below age 60 does not change substantially when Models 3 and 4 introduce additional controls for marital status, place of residence, characteristics of the household, and region of residence at census. The estimates for Pomak men are slightly reduced in Models 3 and 4.

Younger Roma men, whether Christian or Muslim, have substantially higher mortality risks than those of Bulgarian Christians. The mortality excess of Roma men is primarily attributable to their adverse socioeconomic status. Controlling for education alone reduces the excess mortality by 59 per cent [i.e, (0.584 − 0.240)/0.584] for Roma Christians and by 72 per cent for Roma Muslims.

Men 60–90 years old

Model 1 estimates a 9-per-cent higher relative risk of dying for older Turkish men than for Bulgarian Christian men of this age. However, controlling for educational attainment in Model 2 reduces the difference in the relative risk of dying between the two groups to 2 per cent. Once additional socioeconomic characteristics are considered in models 3 and 4, the Turkish disadvantage disappears altogether.

In all hazard models, elderly Pomak men above age 60 have a significantly lower relative risk of death than Bulgarian Christian men of this age. The Pomak advantage in this difference increases once various demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are introduced via models 2 and 3.

As is the case for younger men, both groups of Roma show much higher mortality than the reference category at ages 60–90. In contrast to the results at younger ages, most of this excess remains when socioeconomic characteristics are controlled.

Women 30–60 years old

Young Turkish women experience a 20-per-cent higher relative risk of dying than that of the reference group of Bulgarian Christian women if we consider only age and calendar year in the hazard model (Model 1). The difference in relative risk between these two groups diminishes and eventually disappears when socioeconomic variables are introduced in Models 2 to 4. In contrast, younger Pomak women have lower mortality than the reference group in all models; these differences twice reach statistical significance. As was the case for men, both groups of Roma have much higher mortality than Bulgarian Christians. Even after all controls are instituted, their mortality remains 41–50 per cent higher than that of Bulgarian Christians.

Women 60–90 years old

Elderly Turkish women have significantly higher relative risks of dying than those of Bulgarian women of this age in all four models. Although the differences are not large, they are persistent across models and stand in contrast to the results for Turkish men, whose mortality was below average once account was taken of their social circumstances. Pomak women show patterns more similar to Pomak men. The relative mortality of elderly Roma women remains high in all models. Once all socioeconomic variables are introduced (Model 4), it is older Roma women who suffer comparatively the most, and younger Roma men who suffer the least.

In summary, our results show that Pomak men and women represent the only ethnic/religious group that has lower mortality at both young and old ages than the Bulgarian Christian population. Including region of residence in Model 4 reduces the mortality advantage of the Pomak population in all regressions, indicating that part of the advantage of this ethnic/religious group is that they are heavily concentrated in regions with lower mortality (e.g., southern regions along the Bulgarian-Turkish border). The effects are less clear-cut and more heterogeneous among the Turkish minority group. While Turkish men below age 60 experience a mortality advantage over Bulgarian men, the difference in the relative risk of dying between the two groups disappears above age 60 and a Turkish excess emerges among older women.

The life expectancy estimates in Figure 1 showed that Roma in Bulgaria represent an outlier group in terms of their high mortality levels. The multivariate analyses shown in Table 2 confirmed this pattern. Christian and Muslim Roma of both sexes have substantially higher risks of death than those of the Bulgarian population. The mortality disadvantage among Roma, however, depends partly on their religious background. Relative to Bulgarian Christian men, Christian Roma represent the most disadvantaged group and experience higher relative risks of death than Muslim Roma in all four age/sex categories. Taking account of differences in the socioeconomic status between Roma and the reference group reduces but does not eliminate the Roma excess mortality. The reduction is particularly large for younger men and small for older women. In general, the magnitude of difference in mortality risks between Roma women and Bulgarian Christian women is larger than that observed among the male population.

5 Socioeconomic Differences in Mortality among Muslims and non-Muslims

The census/death certificate link provided the first comprehensive data on social and economic differentials in adult mortality in Bulgaria. While economic circumstances were in a sense the control variables employed to analyse differences in mortality by ethnic/religious group and to identify the Muslim mortality ‘puzzle’ outlined in the previous section, they were important enough to warrant investigation in their own right.

The relationship between mortality and various socioeconomic characteristics included in our models is summarized in Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Table 3.

Relative risk of dying for men aged 30–60, by ethnic/religious group, derived from piecewise-constant proportional hazard models, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic/religious group | ||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Christian Roma | 1.584** | 1.240** | 1.122** | 1.122** |

| Muslim Roma | 1.454** | 1.127** | 1.051+ | 1.040 |

| Turks | 0.999 | 0.820** | 0.811** | 0.844** |

| Pomaks | 0.951 | 0.791** | 0.848** | 0.932* |

| Year | ||||

| 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1994 | 1.030* | 1.039** | 1.036** | 1.036** |

| 1995 | 1.021+ | 1.038** | 1.032** | 1.032** |

| 1996 | 0.994 | 1.019 | 1.011 | 1.011 |

| 1997 | 1.025* | 1.059** | 1.048** | 1.048** |

| 1998 | 1.006 | 1.047** | 1.033** | 1.034** |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9–12 | 0.676** | 0.724** | 0.724** | |

| 13–15 | 0.551** | 0.601** | 0.603** | |

| 16+ | 0.500** | 0.547** | 0.536** | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small town (< 100,000 population) | 0.924** | 1.028* | ||

| Village | 0.829** | 0.914** | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 1.789** | 1.778** | ||

| Divorced | 2.171** | 2.150** | ||

| Widowed | 1.481** | 1.479** | ||

| Standard of accommodation | ||||

| Square meters/HH member | 0.999** | 0.999** | ||

| Non-substandard dwelling | 1 | 1 | ||

| Substandard dwelling (0 score on HH index) | 1.175** | 1.189** | ||

| Highest (4th) quartile HH index | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1st quartile HH index | 1.457** | 1.449** | ||

| 2nd quartile HH index | 1.131** | 1.121** | ||

| 3rd quartile HH index | 1.068** | 1.067** | ||

Notes: p values:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p <0.01.

Model 4 includes controls for region of residence.

Source: As for Table 1

Table 4.

Relative risk of dying for women aged 30–60, by ethnic/religious group, derived from piecewise-constant proportional hazard models, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic/religious group | ||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Christian Roma | 2.101** | 1.730** | 1.499** | 1.500** |

| Muslim Roma | 1.975** | 1.617** | 1.436** | 1.410** |

| Turks | 1.201** | 1.010 | 0.977 | 0.999 |

| Pomaks | 0.986 | 0.834** | 0.851** | 0.964 |

| Year | ||||

| 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1994 | 1.061** | 1.069** | 1.068** | 1.069** |

| 1995 | 1.062** | 1.077** | 1.077** | 1.077** |

| 1996 | 1.053** | 1.076** | 1.075** | 1.076** |

| 1997 | 1.124** | 1.157** | 1.155** | 1.157** |

| 1998 | 1.059** | 1.098** | 1.097** | 1.098** |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9–12 | 0.727** | 0.743** | 0.737** | |

| 13–15 | 0.639** | 0.656** | 0.653** | |

| 16+ | 0.653** | 0.633** | 0.617** | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small town (< 100,000 population) | 0.927** | 0.985 | ||

| Village | 0.867** | 0.918** | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 1.934** | 1.928** | ||

| Divorced | 1.494** | 1.478** | ||

| Widowed | 1.214** | 1.212** | ||

| Standard of accommodation | ||||

| Square meters/HH member | 0.996** | 0.996** | ||

| Non-substandard dwelling | 1 | 1 | ||

| Substandard dwelling (0 score on HH index) | 1.130 | 1.154 | ||

| Highest (4th) quartile HH index | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1st quartile HH index | 1.282** | 1.279** | ||

| 2nd quartile HH index | 1.055** | 1.050** | ||

| 3rd quartile HH index | 1.006 | 1.021 | ||

Notes: p values:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p <0.01.

Model 4 includes controls for region of residence.

Source: As for Table 1

Table 5.

Relative risk of dying for men aged 60–90, by ethnic/religious group, derived from piecewise-constant proportional hazard models, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic/religious group | ||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Christian Roma | 1.681** | 1.569** | 1.409** | 1.406** |

| Muslim Roma | 1.591** | 1.479** | 1.359** | 1.330** |

| Turks | 1.088** | 1.020* | 0.987 | 0.988 |

| Pomaks | 0.955* | 0.896** | 0.889** | 0.946* |

| Year | ||||

| 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1994 | 1.007 | 1.010 | 1.014* | 1.014* |

| 1995 | 1.029** | 1.034** | 1.043** | 1.043** |

| 1996 | 1.030** | 1.039** | 1.051** | 1.051** |

| 1997 | 1.065** | 1.078** | 1.094** | 1.095** |

| 1998 | 1.031** | 1.047** | 1.066** | 1.067** |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9–12 | 0.828** | 0.848** | 0.850** | |

| 13–15 | 0.725** | 0.750** | 0.751** | |

| 16+ | 0.704** | 0.733** | 0.733** | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small town (< 100,000 population) | 0.998 | 1.032** | ||

| Village | 0.921** | 0.950** | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 1.125** | 1.127** | ||

| Divorced | 1.507** | 1.504** | ||

| Widowed | 1.209** | 1.209** | ||

| Standard of accommodation | ||||

| Square meters/HH member | 0.996** | 0.996** | ||

| Non-substandard dwelling | 1 | 1 | ||

| Substandard dwelling (0 score on HH index) | 1.158** | 1.163** | ||

| Highest (4th) quartile HH index | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1st quartile HH index | 1.181** | 1.177** | ||

| 2nd quartile HH index | 1.063** | 1.059** | ||

| 3rd quartile HH index | 1.008 | 1.013 | ||

Notes: p values:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p <0.01.

Model 4 includes controls for region of residence.

Source: As for Table 1

Table 6.

Relative risk of dying for women aged 60–90, by ethnic/religious group, derived from piecewise-constant proportional hazard models, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic/religious group | ||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Christian Roma | 1.871** | 1.787** | 1.630** | 1.619** |

| Muslim Roma | 1.744** | 1.662** | 1.525** | 1.485** |

| Turks | 1.108** | 1.061** | 1.019* | 1.033** |

| Pomaks | 0.859** | 0.824** | 0.798** | 0.953+ |

| Year | ||||

| 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1994 | 1.001 | 1.003 | 1.006 | 1.006 |

| 1995 | 1.029** | 1.034** | 1.040** | 1.040** |

| 1996 | 1.047** | 1.054** | 1.064** | 1.064** |

| 1997 | 1.092** | 1.103** | 1.116** | 1.117** |

| 1998 | 1.030** | 1.043** | 1.059** | 1.060** |

| Years of education | ||||

| 0–8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9–12 | 0.788** | 0.810** | 0.810** | |

| 13–15 | 0.705** | 0.731** | 0.732** | |

| 16+ | 0.734** | 0.761** | 0.763** | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Big city (100,000+ population) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Small town (< 100,000 population) | 1.015* | 1.033** | ||

| Village | 0.987 | 1.001 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 | 1 | ||

| Single | 1.257** | 1.267** | ||

| Divorced | 1.235** | 1.235** | ||

| Widowed | 1.126** | 1.127** | ||

| Standard of accommodation | ||||

| Square meters/HH member | 0.996** | 0.995** | ||

| Non-substandard dwelling | 1 | 1 | ||

| Substandard dwelling (0 score on HH index) | 1.012 | 1.017 | ||

| Highest (4th) quartile HH index | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1st quartile HH index | 1.111** | 1.104** | ||

| 2nd quartile HH index | 1.055** | 1.050** | ||

| 3rd quartile HH index | 0.997 (0.010) | 1.006 (0.010) | ||

Notes: p values:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p <0.01.

Model 4 includes controls for region of residence.

Source: As for Table 1

In all models, we estimated statistically significant effects of calendar year. Consistent with deteriorating economic conditions over the period, Bulgarian mortality rose during the period of observation from its level in the reference year 1993. This increase was observed for all age/sex groups. The year with the highest level of mortality was 1997.

In contrast to most other Eastern European countries and the Newly Independent States (Watson 1995; Mackenbach et al. 1999; McKee and Shkolnikov 2001), the increase in mortality was greater for women than for men. For example, the relative risk of death for young women rose in 1997 by 12 per cent (Model 1) to 15 per cent (Model 4) above the reference year 1993, and the respective increase for older women was between 9 and 12 per cent. For young men, the estimates show a 3-per-cent (Model 1) to 6-per-cent (Model 4) increase in the relative risk of dying in 1997 above that of 1993, and for old men the respective figures are 7 per cent to 10 per cent.

Education is highly significantly associated with the risk of death in Bulgaria in all models and for both sexes and age ranges. The educational gradient is most pronounced among young men. Marital status is significantly associated with the risk of dying. Young divorced men in Bulgaria are particularly disadvantaged and experience more than double the risk of death of married men below age 60. Single young men and women are also at great risk compared to their married counterparts.

In Model 3, living in small cities (i.e., below 100,000 in population) or villages is associated with 7-per-cent to 13-per-cent lower relative risk of death for both sexes and age ranges than that of individuals living in big cities. Exceptions are women above age 60 in small cities, whose mortality is elevated by about 2 per cent. The association of place of residence with risk of death changes modestly once we controlled in Model 4 for region of residence.

In Models 3 and 4 we also included variables reflecting household characteristics. Living and housing conditions differ substantially between the ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria, with Roma typically having the worst living environment (see for instance Tomova 1995, p. 158). We calculated the square metres of living space available per household member. The estimates for this variable are stable across all models, and suggest that more living space per household member is significantly associated with reduced mortality for all age/sex groups. Using the household characteristics collected at census, we also constructed a household-quality index that captured important aspects of the quality of the environment in which people lived. We used the following household items to construct the index: access to different types of central water supply, access to different types of warm water supply, types of lavatory in the dwelling, availability of bath in the dwelling, and types of drain system in the dwelling. Different scales were used to measure these items. To allow a straightforward interpretation of the index, we divided each of the variables by its maximum value so that the effect of going from the lowest to the highest level within each of these categories had the same effect on the index. The sum of the values on all household variables constituted the score on the household index scale. In the models, we used quartiles of the index to indicate the position of each individual. A large proportion of individuals live in substandard dwellings, a separate category used in the census form.

There is a clear gradient in mortality associated with the position of the household on the index scale: living in a household that is in the 1st quartile of the household index is associated with a relative risk of death for young women that is 28-per-cent higher for young women and about 46 per cent higher for young men than for those positioned in the highest quartile of the index. The effect is substantially smaller for elderly women and men and varies from 10 to 18 per cent respectively. The difference in the risk of death between those living in a household scoring in the 2nd quartile of the household index and the wealthiest households is smaller and varies from a 5-per-cent higher risk of death for women and elderly men to an estimated 13-per-cent higher risk of death for men below age 60. The effect of the 3rd quartiles of the household index is statistically significant only for young men.

Substandard dwellings are scored as zero on the household index and are reported as a separate category. As a reference category for the household index in Models 3 and 4, we use living in a household scoring in the highest quartile of the index. Living in a substandard dwelling is statistically significant only for men. Its effect is associated with 16–19-percent higher risk of death than that of young or elderly men living in households scoring in the highest quartiles.

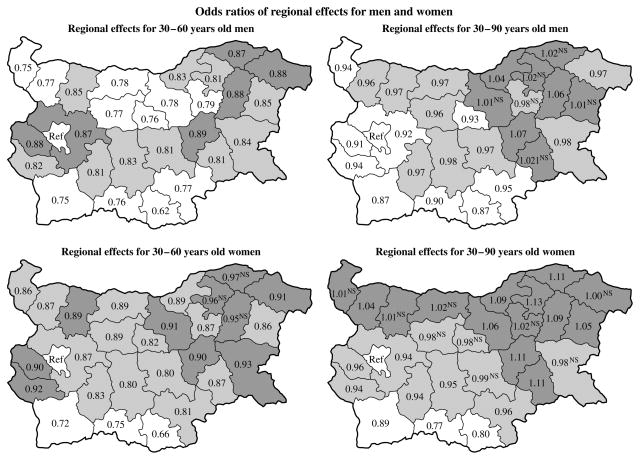

In Model 4 we added a set of dummy variables representing region of residence at census. The association of these variables with the risk of death is shown in Figure 2. The reference region is the metropolitan area of the capital Sofia, and the coefficients show the extent to which the remaining regions differ from the reference region. All regional effects are statistically significant for young men and indicate that men living outside of metropolitan Sofia have a lower risk of death than the capital’s residents. The pattern is very similar for young women, with the exception that the coefficients of three of the north-eastern regions are not statistically significant. The picture is somewhat different for older men and women. While some regions situated in the middle of the country are associated with lower risk of death, individuals living in regions along the north-eastern and south-eastern parts of the country experience higher risk of death than in Sofia. Three regions along the Greek and Turkish borders are systematically associated with lower risk of death.

Figure 2.

Relative risks of dying by region of residence.

Source: As for Table 1.

6 Ethnic/religious differences in mortality by cause of death

In this section, we present ethnic differences in mortality according to major causes of death. We retained the four age/sex groupings and the five ethnic groupings that were used earlier. Information on causes of death was obtained from death certificates. We defined the following groups of causes of death: infectious and parasitic diseases, neoplasms, heart diseases, strokes, diseases of the respiratory system, injuries and poisoning, and all other causes. Causes of death were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, revision 9 (ICD-9). We used as a standard for these computations the Bulgarian Christian population of both sexes combined.

Figure 3 presents age-standardized death rates by cause in the four age/sex groups. As suggested by the life tables and regression analyses, the two Roma groups have by far the highest mortality levels in each of the four age/sex categories; death rates of the remaining ethnic/religious groups are similar to one another. However, Turks have higher mortality than Bulgarian Christians in all cases except that of younger men, an exception that is a possible indicator of the role played by life-style factors.

Figure 3.

Age-standardised mortality by ethnic/religious group and sex—cause specific contributions.

Source: As for Table 1.

Table 7 presents age-standardized death rates according to these major causal groupings. It is clear that both Christian and Muslim Roma have higher death rates from virtually every cause in every age/sex group. To obtain the contribution of each cause of death to the difference between age-standardized death rates (ASDR) for ethnic/religious groups, we calculated for each group of causes of death the difference between age-standardized death rate (ASDR) for Roma Muslims and the ASDR for Bulgarian Christians. We then divided this difference by the difference in ASDR for all causes combined between the two respective ethnic/religious groups as follows: , where Mus refers to the Roma Muslim populations and Bulg refers to the Bulgarian Christian population. In terms of their contribution to Roma/Bulgarian differences in mortality from all causes combined, cardiovascular diseases are the most important. Comparing Muslim Roma to Bulgarian Christians, heart diseases and stroke account for 62 per cent of the difference in all-cause mortality for men aged 30–60 and 68 per cent of the difference for men aged 60–90. For women, the comparable figures are 81 per cent and 75 per cent. Respiratory diseases account for 10–22 per cent of this ethnic difference.

Table 7.

Age-standardized death rate per 1,000 by cause of death and ethnic/religious groups, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Infectious/parasitic disease | Neoplasm | Heart disease | Stroke | Respiratory disease | Injury and poisoning | All other | All causes combined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men 30–60 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.101 | 1.790 | 2.520 | 1.002 | 0.333 | 1.112 | 1.333 | 8.191 |

| Turks | 0.102 | 1.678 | 2.690 | 1.037 | 0.511 | 1.003 | 0.979 | 8.000 |

| Pomaks | 0.097 | 1.895 | 2.399 | 0.746 | 0.674 | 0.920 | 0.970 | 7.702 |

| Christian Roma | 0.305 | 2.515 | 4.436 | 1.950 | 0.750 | 1.383 | 1.631 | 12.971 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.242 | 2.404 | 4.235 | 1.535 | 1.034 | 1.047 | 1.347 | 11.844 |

| Men 60–90 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.247 | 7.757 | 21.702 | 11.642 | 2.621 | 1.490 | 10.689 | 56.147 |

| Turks | 0.364 | 6.570 | 26.163 | 11.152 | 6.007 | 0.991 | 9.462 | 60.710 |

| Pomaks | 0.337 | 7.647 | 23.010 | 8.094 | 6.703 | 0.892 | 6.647 | 53.329 |

| Christian Roma | 0.787 | 9.240 | 37.935 | 17.386 | 6.475 | 1.755 | 13.564 | 87.141 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.470 | 7.885 | 34.537 | 17.609 | 8.569 | 1.642 | 13.053 | 83.764 |

| Women 30–60 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.022 | 1.141 | 0.717 | 0.416 | 0.087 | 0.216 | 0.440 | 3.038 |

| Turks | 0.031 | 0.833 | 1.126 | 0.674 | 0.134 | 0.185 | 0.543 | 3.525 |

| Pomaks | 0.015 | 0.858 | 0.938 | 0.454 | 0.100 | 0.163 | 0.445 | 2.973 |

| Christian Roma | 0.104 | 1.175 | 2.468 | 1.352 | 0.249 | 0.264 | 0.823 | 6.434 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.031 | 1.008 | 2.400 | 1.173 | 0.388 | 0.204 | 0.840 | 6.044 |

| Women 60–90 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.093 | 4.345 | 14.552 | 8.890 | 1.238 | 0.563 | 7.806 | 37.486 |

| Turks | 0.106 | 2.770 | 18.786 | 9.823 | 2.681 | 0.314 | 7.251 | 41.730 |

| Pomaks | 0.122 | 2.976 | 15.476 | 6.901 | 2.771 | 0.323 | 4.278 | 32.847 |

| Christian Roma | 0.333 | 4.215 | 31.098 | 14.746 | 3.885 | 0.892 | 9.659 | 64.827 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.147 | 4.199 | 26.926 | 14.982 | 4.429 | 0.788 | 10.583 | 62.053 |

Source: As for Table 1

Results are very similar for Christian Roma. Neoplasms contribute 15–17 per cent of the difference in ASDRs between Roma and Bulgarian Christians for younger men; as will be shown below, most of that difference is attributable to lung and respiratory cancers.

Apart from the Roma/non-Roma contrasts in Table 7, differences in cause-specific mortality by ethnicity/religion are small. Death rates from infectious and parasitic diseases are sometimes used as an indicator of the adequacy of health services, since most such deaths are readily prevented. It is therefore noteworthy that ethnic differences in death rates from infectious and parasitic diseases are quite small, apart from the large disparities involving the Roma. Turkish Muslims and the Muslim Pomaks do not appear disadvantaged on this indicator.

There are several exceptions to the rather unstructured death-rate differences among the non-Roma groups. Death rates from respiratory diseases are much lower among Bulgarian Christians than among other ethnic groups in all four age/sex categories. As shown below, similar differences exist for lung cancer in men. In addition, Turks have higher death rates from heart disease and strokes than do Bulgarian Christians or Pomaks in nearly all comparisons. Such death rates are highly responsive to technology-intensive medical and surgical procedures, and it is possible that Turks do not have the same access to these procedures as other groups. For instance, during the 1990s, medical personnel was unevenly distributed across regions, with a high concentration in urban centres and limited coverage in poor rural areas, which are predominantly inhabited by ethnic/religious minorities such as Turks or Pomaks (; United Nations Development Programme 1996; Tomova 2005).

7 Life-style factors and ethnic/religious differences in mortality

Unhealthy personal habits such as smoking and excessive drinking are among the factors that have been cited as the driving forces behind the unfavourable mortality trends in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Cockerham 2000; Laaksonen et al. 200; Cockerham et al. 2004). Among the life-style factors, excessive alcohol consumption and the very poor quality of homemade alcohol have been cited more frequently than others (Szucs et al. 2005). While a low level of alcohol consumption among Muslims appears to be a general phenomenon (Cockerham et al. 2004), smoking differences among ethnic and religious groups are less clear-cut. The Islamic religion does not ban tobacco consumption. Turkey was one of the first countries to develop a high prevalence of smoking and maintains a very high prevalence of 74 per cent among adult men today (El-Agha and Gokmen 2002). In a study of migrant populations in Belgium, Deboosere and Gadeyne (2005) found that lung-cancer mortality among Turkish men was one of the highest among migrants and was comparable to the levels found among Belgian, French, and Italian men. In contrast, Moroccan migrants to France have lower levels of lung cancer than the locally born population (Khlat 1995; Darmon and Khlat 2001). In the presence of the substantial differences in behavioural and dietary habits observed between Muslim and non-Muslim religious groups overall, we investigated whether differences in life styles and behaviour between Muslims and non-Muslims were reflected in cause-specific mortality differentials among the ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria.

We selected six causes of death that were most likely to reflect life-style and behavioural differences between the ethnic/religious groups. Table 8 shows age-standardized death rate per 1,000 (ASDR) for smoking-related cancers, alcohol-related causes of death, suicides, homicides, traffic accidents, and other accidents, calculated for the ethnic/religious groups investigated in this paper. Smoking-related cancers include malignant neoplasm of the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx, cancer of upper aerdigestive tract and larynx, and cancer of trachea, bronchus, and lung. Cancers of the lung and respiratory system are a clear reflection of smoking patterns, since approximately 80–90 per cent of deaths from this cause in heavy smoking groups are attributable to smoking (Preston and Wang 2006).

Table 8.

Age-standardized death rate per 1,000 for selected ‘lifestyle’ causes of death, by ethnic/religious groups, Bulgaria 1993–98

| Smoking-related cancer | Alcohol-related cause | Suicide | Homicide | Traffic accident | Other accident | All other causes | All causes combined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men 30–60 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.774 | 0.589 | 0.266 | 0.088 | 0.241 | 0.453 | 5.781 | 8.191 |

| Turks | 0.710 | 0.471 | 0.180 | 0.061 | 0.118 | 0.448 | 5.714 | 7.702 |

| Pomaks | 0.811 | 0.398 | 0.217 | 0.092 | 0.196 | 0.425 | 5.862 | 8.000 |

| Christian Roma | 1.251 | 0.546 | 0.271 | 0.267 | 0.287 | 0.460 | 9.889 | 12.971 |

| Muslim Roma | 1.372 | 0.370 | 0.210 | 0.165 | 0.196 | 0.449 | 9.082 | 11.844 |

| Men 60–90 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 2.283 | 1.087 | 0.556 | 0.064 | 0.256 | 0.572 | 51.329 | 56.147 |

| Turks | 2.850 | 0.833 | 0.283 | 0.070 | 0.121 | 0.353 | 48.820 | 53.330 |

| Pomaks | 2.722 | 0.810 | 0.336 | 0.046 | 0.151 | 0.446 | 56.199 | 60.710 |

| Christian Roma | 4.025 | 1.442 | 0.565 | 0.203 | 0.461 | 0.444 | 80.002 | 87.141 |

| Muslim Roma | 4.204 | 1.256 | 0.345 | 0.229 | 0.291 | 0.608 | 76.830 | 83.764 |

| Women 30–60 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.090 | 0.076 | 0.081 | 0.016 | 0.048 | 0.064 | 2.663 | 3.038 |

| Turks | 0.078 | 0.043 | 0.082 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 2.706 | 2.973 |

| Pomaks | 0.086 | 0.068 | 0.069 | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.059 | 3.191 | 3.525 |

| Christian Roma | 0.265 | 0.138 | 0.070 | 0.061 | 0.050 | 0.083 | 5.767 | 6.434 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.203 | 0.110 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.059 | 0.071 | 5.538 | 6.044 |

| Women 60–90 years old | ||||||||

| Bulgarian Christians | 0.400 | 0.332 | 0.231 | 0.023 | 0.098 | 0.193 | 36.209 | 37.486 |

| Turks | 0.253 | 0.237 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.142 | 32.035 | 32.847 |

| Pomaks | 0.412 | 0.307 | 0.087 | 0.025 | 0.053 | 0.144 | 40.704 | 41.730 |

| Christian Roma | 0.921 | 0.588 | 0.179 | 0.105 | 0.233 | 0.321 | 62.479 | 64.827 |

| Muslim Roma | 0.950 | 0.436 | 0.081 | 0.089 | 0.273 | 0.346 | 59.879 | 62.053 |

Source: As for Table 1.

For all age/sex groups, Roma (whether Christian or Muslim) have by far the highest death rates from smoking-related cancers. It is clear that a history of heavy smoking among Roma is having a serious impact on their mortality profile, an impact that could be expected to appear in cardiovascular diseases as well. Among men, Bulgarian Christians have the lowest death rate in both age intervals from lung and respiratory cancers. However, this pattern may reflect not only differences in smoking behaviour and lower prevalence of smoking among Bulgarian Christians than among Muslim men, but also occupational differences between groups: Muslim men were more likely to be employed in hazardous occupations such as mining, or be exposed to adverse working conditions in the heavy industry, a known source of harm to the lung and respiratory systems (Tomova 2005). Among women, the results are more clear-cut: Bulgarian Christians, who have higher prevalence of smoking, also experience higher rates of mortality from cancers of the lung and respiratory system than do Turkish or Pomak women.

Alcohol-related causes of death include cancer of the esophagus, mental and behavioural disorders caused by use of alcohol, alcoholic liver disease, fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver, and alcohol poisoning. The consequences of heavy alcohol consumption are spread across many causes of death in Eastern Europe: poisoning, suicide, homicide, accidents, and cardiovascular diseases (Guillot et al. 2007). There is no pure measure of the consequences of alcohol consumption equivalent to that of lung cancer for smoking. A comparison of death rates in Table 8 of Turks and Pomaks with those of Bulgarian Christians for alcohol-related causes, suicides, homicides, traffic accidents and other accidents shows that both Turkish and Pomak men and women have lower death rates in 37 out of 40 comparisons. It is likely that lower alcohol consumption among Turks and Pomaks is related to this mortality pattern. It is particularly noteworthy that among young men, Turks, Pomaks and Muslim Roma have lower death rates from alcohol-related causes than do Bulgarian Christian men, while the death rate of Christian Roma resembles closely that of the Bulgarian Christian men. Similarly, Turkish and Pomak women in both age groups have lower mortality from alcohol-related causes of death than do Bulgarian Christian women. In contrast to the pattern for men, Roma women of both religious groups have higher death rates from alcohol-related causes of death than Bulgarian Christian women. Once again, a carry-over of these patterns into cardiovascular diseases was to be expected.

The ethnic/religious pattern of mortality from suicide is intriguing. In three of the four age/sex groups (in all except younger women), the two highest death rates from suicide occur among Christian Bulgarians and Christian Roma. This is the only cause of death for which religious differences appear to dominate ethnic differences: Muslim Roma have suicide death rates closer to those of Pomaks and Turks than to those of Christian Roma in all four age/sex categories, and in three of the four the differences are quite large. The other Muslim group, the Pomaks, have lower death rates from suicide than the two Christian groups in 7 of 8 comparisons in Table 8. The death rates from suicide mortality increase with age, a pattern shown also in other Eastern European countries (Skog and Elekes 1993).

The pattern of suicide mortality that we have uncovered is consistent with previous studies. Several studies have connected alcohol abuse with suicides (Skog and Elekes 1993; Wasserman et al. 1994; Värnik et al. 1998), and evidence exists that suicide mortality among men is higher in countries with high alcohol consumption and lower in predominantly Muslim countries (Wasserman et al. 1994), or among Muslim migrant populations in Europe (Khlat and Courbage 1996; Deboosere and Gadeyne 2005). A higher death rate from suicide among Christians than among Muslims has been noted across countries (Pritchard and Amanullah 2007) and within countries (Eskin 2004). Islam strictly forbids alcohol consumption (Sarhill et al. 2001). In contrast to the Bible, which is silent on suicide as a moral issue, the Holy Quran explicitly condemns suicide. On the other hand, high mortality from suicide among Christians has been attributed to the feelings of guilt engendered by religious doctrines that emphasize personal responsibility, as well as lower levels of social solidarity (Durkheim 1992; Marmot 2005). Homicide presents a much clearer and more conventional ethnic pattern. In each of the four age/sex categories, the two Roma groups have the two highest death rates from homicide. In three of the four groups, the distinction of having the lowest homicide rate belongs to the Pomaks. Interestingly, exactly this pattern is maintained for the sizable number of deaths from ‘other accidents’: the two Roma groups have the two highest death rates in all age/sex groups, and Pomaks the lowest in three of four.

Death rates from traffic accidents are a function of the number of miles driven, which generally increases with income per, and the degree of danger posed by each mile, which generally decreases with income per head. These conflicting tendencies produce a mixed ethnic pattern of mortality from this cause. But for each age/sex group, the Roma have the highest death rate from traffic accidents, and in three of the four age/sex groups the two Roma groups have the two highest death rates. The exceptionally high death rates from traffic accidents of older Roma men and women are particularly noteworthy. In contrast to most populations, death rates from traffic accidents rise in Bulgaria with age for all groups except Turkish men.

To summarize some of the main findings of this section, the Roma groups exhibit unusually high mortality from lung cancer, traffic accidents, other accidents, and homicide. Clearly, life-style factors are contributing to their unusually high mortality from all causes combined. Turks and Pomaks generally have lower mortality than the ethnic majority from causes thought to be related to excessive consumption of alcohol, although the multifactorial nature of these mortality rubrics precludes the drawing of any definitive conclusions. Christian groups have higher death rates than Muslims from suicide, the only instance in which Christian Roma break ranks with their Muslim Roma counterparts.

8 Summary and discussion

Our results show that the mortality of most minorities in Bulgaria is similar in levels and patterns to that of the Bulgarian Christian Orthodox majority. This observation is inconsistent with many economically-oriented interpretations of mortality variation, including those that cite socioeconomic deprivation, limited access to health care, or deteriorating housing conditions for the observed mortality increase in Central and Eastern Europe during the 1990s (Delcheva et al. 1997; Mackenbach et al. 1999; Davis 2000). Turks and Pomaks score poorly on all these factors compared to the Bulgarian Christian Orthodox majority. Nevertheless, these two Muslim groups enjoy mortality levels similar to that of ethnic Christian Bulgarians. When socioeconomic conditions are controlled, Muslim men aged 30–60 have significantly lower mortality than do Bulgarian Christians. Among Pomaks, this advantage extends to all age/sex groups considered. In this respect, the demographic position of Muslim ethnic/religious groups in Bulgaria (and possibly in other European countries for which no data exist) is similar to that of Hispanics in the United States, a group of relatively low socio-economic standing that enjoys better-than-average mortality (Elo and Preston 1997; Elo et al. 2004; Palloni and Arias 2004). This phenomenon has been dubbed the ’Hispanic paradox’ and has been the subject of considerable research because of the light that it sheds on the determinants of mortality. We attribute the mortality advantage of Muslim populations—when education is controlled—to life-style factors and to social relations that differ between Muslims and non-Muslims.

To investigate these factors, we used detailed information available on causes of death. Two causes of death—suicide and alcohol-related causes— are instrumental in distinguishing the factors involved. Suicide mortality is the cause of death for which religious differences appear to dominate ethnic differences in our analysis. Muslim groups in Bulgaria have lower suicide mortality than the Christian population. Moreover, the suicide death rates of Muslim Roma are closer to those of other Muslim groups than to their Christian counterparts. Although serious concerns about the under-reporting of suicide in Muslim populations exist (Lester 2006; Pritchard and Amanullah 2007), there is no evidence that discrepancies by religion in reporting suicides exist in Bulgaria.

Differences in smoking behaviour are mirrored in mortality from lung cancer and cancers of the respiratory system. Among women, Bulgarian Christians, who have a higher prevalence of smoking, experience higher rates of cancers of the lung and respiratory system than do Turkish or Pomak women. In contrast, smoking is highly prevalent among Muslim men in general, and Bulgarian Muslims are no exception. Muslim men have higher death rates from cancers of the lung and respiratory system than do Bulgarian Christians.

Differences in mortality are evident not only across but also within religious groups. Pomaks, whose socioeconomic position, religious affiliation, life style, and social standing mirror the position of the Turkish minority, had the lowest mortality of any ethnic/religious group during the 1990s. Pomaks represent a very closed and isolated community with a strong religious identity and social ties (Poulton 1991). Muslim Roma, who represent religiously and socially a more coherent group, have a mortality advantage over Christian Roma. It is possible that membership in a socially and religiously cohesive group contributes to lower mortality. The benefits may be material, or social-psychological in nature, and they may become more pronounced in a situation of economic crisis. Such factors may also be reflected in the differences between Christian and Muslim Roma in suicide rate.

The evidence makes it abundantly clear that Roma, both Muslim and Christian, experience the highest mortality risks in Bulgaria. The marginalized status of Roma in Bulgaria is replicated throughout Eastern Europe. Roma represent the largest minority population in Europe and our results suggest that their health conditions require special attention.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Institutes of Health-National Institute on Aging, (Grant Number P30 AG12836), the Boettner Center for Pensions and Retirement Security at the University of Pennsylvania, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute of Child Health, and the Development Population Research Infrastructure Program R24 HD-044964 at the University of Pennsylvania. The compilation of the Bulgarian dataset was performed at the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (NSI) and funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA 10168). We gratefully acknowledge the support received for this research by the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (NSI), and we are gratefully indebted to Ekaterina Arnaudova, Ivan Balev and Mariana Dimova for their help and support in establishing this database.

Appendix

Information on ethnicity and religion in the dataset was available only from the census records and was based on self-identification. This imposed the limitation that multiple records for the same individual could not be used to verify the individual’s ethnic and religious self-identification. Verification of ethnic/religious membership was potentially important since it has been shown that members of low-standing ethnic/religious groups tend to identify themselves with other, more prestigious groups (Tomova 2005, 1995; UNDP 2003). The problem of changing ethnic self-identification is particularly pronounced among the Roma population and this tendency is persistently evident in the population censuses carried out in post-Ottoman Bulgaria (Tomova 1995; Vladimirova 2007). According to Tomova (1995), the way Roma identify themselves to others depends on various situational factors. For instance in her sample, one in ten of the better-educated Roma living in big urban centres identified themselves as ethnic Bulgarians. There is also evidence to suggest that official demographic data systematically under-count the Roma population, who tend to identify with local ethnic and religious groups (UNDP 2003). In addition, Roma represent the most diverse ethnic community in Bulgaria in terms of religion, mother tongue, identity, and customs (Tomova et al. 2000; Revenga et al. 2002; Tomova 2005;), and the criteria for assigning individuals to this ethnic group are not straightforward.

The problem with changing ethnic/religious membership is not particularly prominent among the Turks and Bulgarian Muslims (Pomaks). With the exception of the Revival Period, few disputes exist about the identity of Turks as a separate ethnic/religious group (Lozanova et al. 2005). Whether the Pomaks (Bulgarian Muslims) constitute a separate ethnic group is not clear. They are usually identified as a Slavic minority, primarily concentrated in the mountainous regions of the Rhodope mountains, with Bulgarian language as their mother tongue, but whose religion and customs are Muslim (Poulton 1991; Georgieva 2001). According to Poulton (1991, p. 114), Pomaks are more Islamic in their cultural customs, traditions, and religious practices than are ethnic Turks since religion is the only factor that differentiates them from Slavic Bulgarians. Existing evidence suggests that Pomaks are also under-counted in the official statistics.

As noted by Vladimirova (2007, p. 155) the census with the most complete information about the ethnic composition of the Bulgarian population is that of 1992, on which our analyses were based. The 1992 census asked a set of three questions on ethnicity, religion, and mother tongue. We assigned all individuals in our analysis to a certain ethnic or religious group by combining responses to these three questions. In particular, all individuals who identified themselves as being of Bulgarian ethnicity, speaking the Bulgarian language, and Christian Orthodox in religion were classified in these analyses as Bulgarian Christians. We considered Turks to be those who listed Turkish either as an ethnic group or a mother tongue and whose religion was Muslim. Turks identifying their religion as Christian were dropped from the analysis. According to the 1992 Census, 91.86 per cent of Turks were Sunni Muslims and 7.10 per cent were Shiite Muslims. Together, they constituted 9.43 per cent of the Bulgarian population. In a similar manner, individuals were classified as Roma if they listed Roma either as an ethnicity or a mother tongue. Roma were subdivided into Muslim and Christian according to their stated religion. Roma made up 3.7 per cent of the Bulgarian population in 1992, of whom about 39 per cent were Muslims. Finally, Pomaks were those who listed Pomak as their ethnicity and whose religion was Muslim. They represented 1.2 per cent of the Bulgarian population.

All other observations were dropped, including 69,506 cases (or 0.98 per cent) with Bulgarian ethnicity and Muslim religion because we were not able to assign these cases unambiguously to one of the ethnic/religious groups included in our analyses.

The way ethnic/religious groups were identified in our analyses had several potential implications for our results. If more advantaged members of minority groups, such as Roma and Pomaks, were more likely to be misclassified into some other group or be under-counted, we may have underestimated their mortality and overestimated the mortality of other groups. In other words, the mortality differentials between the minority groups and the other groups may be even larger than the ones we described.

While especially the Roma tend to self-identify with other more prestigious groups and change ethnic membership depending on circumstances (Tomova 1995, 2005), an under-count because of migration is of greater concern in the case of the Turkish minority (Kaltchev 2005). The largest wave of out-migration, to Turkey, of an ethno-political character in recent time was in the period 1989–1992, i.e. before the census enumeration in 1992. These Turks were not enumerated in the census, and thus did not contribute to our mortality estimates. Subsequent out-migration that coincided with the period of our study had an economic character. Those who left the country were primarily young and well educated people, concentrated among the Bulgarian Orthodox population.

Contributor Information

Iliana V. Kohler, Email: iliana@pop.upenn.edu, Population Aging Research Center (PARC), Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6299.

Samuel H. Preston, Email: spreston@sas.upenn.edu, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Balabanova D, Mckee M. Patterns of alcohol consumption in Bulgaria. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 1999;34(4):622–628. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Marmot M. East-West health divide and potential explanations. In: Hertzman C, Kelly S, Bobak M, editors. East-West Life Expectancy Gap in Europe. Environmental and Non-Environmental Determinants. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996a. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Marmot M. East-West mortality divide and its potential explanations: proposed research agenda. British Medical Journal. 1996b;312(7028):421–425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Marmot M. Alcohol and mortality in Russia: Is it different than elsewhere? Annals of Epidemiology. 1999;9(6):335–338. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson P. The European Health Divide: A matter of financial or social capital? Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(9):1985–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham W. Health lifestyles and the absence of the Russian middle class. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2007;29(3):457–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham WC. The social determinants of the decline of life expectancy in Russia and Eastern Europe: A lifestyle explanation. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(2):117–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham WC. Health lifestyles in Russia. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(9):1313–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham WC, Hinote BP, Abbott P, Haerpfer C. Health life styles in Central Asia: The case of Kazakhastan and Kyrgyzstan. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(7):1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]