Abstract

Overgeneral autobiographical memory (AM), the tendency to recall categories of events when asked to provide specific instances from one's life, is purported to be a marker of depression vulnerability that develops in childhood. Although early adolescence is a period of risk for depression onset especially among girls, prospective examination of this putative risk factor is lacking. The current study examined the prospective associations between AM recall and depressive symptomatology in an enriched community sample of predominantly African American girls. Girls (n=195) were interviewed about depressive symptoms at ages 11 and 12 years, and AM recall was assessed at age 11. The findings showed that overgeneral retrieval to positive, but not negative, cue words predicted subsequent depressive symptoms after controlling for age 11 symptoms, race, poverty, and Verbal IQ. A moderating effect of race was also shown, whereby overgeneral AM bias predicted depressive symptoms more strongly among European American girls. The findings are discussed in relation to the broader literature on depression affective biases.

Keywords: Girls, autobiographical memory, depression, risk factors

In recent years there has been increasing theoretical interest in, and empirical evidence for, autobiographical memory (AM) as an idiosyncratic, self-referent cognitive style that is associated with major depressive disorder. A wealth of studies have now shown that when asked to recall a specific event from their past, individuals with acute or chronic major depression typically retrieve a disproportionate number of overgeneral memories compared with non-depressed individuals (Goddard, Dritschel & Burton, 1996; Kuyken & Dalgleish, 1995; van Vreeswijk & de Wilde, 2004; Williams, Barnhofer, Crane, Hermans, Raes, Watkins, & Dalgleish, 2007). For example, an overgeneral memory might consist of: “I feel happy when I play tennis” compared with a specific memory such as “I felt happy this morning when I played tennis”. The same overgeneral bias has been reported in studies that experimentally induced low mood in research participants (Yeung, Dalgleish, Golden & Schartau, 1988), and also in studies of adults whose depression was in remission (Williams & Dritschel, 1988). Of particular clinical importance, an overgeneral memory bias appears to predict the course of, and recovery from, depressive episodes (Brittelbank, Scott, Williams & Ferrier, 1993).

Williams (1996) posited that reduced AM specificity develops as a means of regulating negative affect by repressing the recall of distressing experiences, which over time results in characteristic over-general remembering of personal events. Some empirical studies have indeed shown a direct relationship between overgeneral AM and retrospectively reported trauma during childhood (Henderson, Hargreaves, Gregory & Williams, 2002), as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (McNally, Lasko, Macklin & Pitman, 1995). In other studies, however, such associations have not been found (Kuyken, Howell & Dalgleish, 2006). More recently, the role of impaired executive control has been incorporated into the model to further explain the tendency of depressed individuals to retrieve overgeneral memories (Williams, J. et al., 2007). This updated model has been supported by research showing that verbal fluency mediates the relationship between overgeneral recall and depressed mood in adults (Dalgleish et al., 2007).

Because transient mood fluctuations in clinical samples of adults do not appear to be associated with increased AM specificity (Brittlebank et al., 1993; Mackinger, Pachinger, Leibetseder & Fartacek, 2000; Nandrino, Pezard, Poste, Reveillere & Beaune, 2002), it has been suggested that overgeneral retrieval represents a trait-like marker of vulnerability to depression (Goddard et al., 1996; Kuyken & Brewin, 1995; Williams, Watts, MacLeod & Mathews, 1997) that develops in childhood. Retrospective reports of adolescents and adults lend some support to this notion (Kuyken et al., 2006; Orbach, Lamb, Sternberg, Williams & Dawud-Noursi, 2001), as do data from a growing number of studies examining concurrent associations between AM style and depression in children and adolescents. Consistent with the adult literature, results indicate that clinic-referred samples of depressed adolescents generate disproportionately more overgeneral memories to positive and negative cue words than non-depressed adolescents (Kuyken et al., 2006; Park, Goodyer & Teasdale, 2002; Swales, Williams & Wood, 2001). Further, Park and colleagues reported higher rates of overgeneral recall among adolescents with a first episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) suggesting that this AM bias is not attributable to the scarring effects of prior depressive episodes (Park et al., 2002). Less consistent evidence has emerged from studies examining the association between AM recall style and continuous measures of depressed mood in adolescents (de Decker, Hermans, Raes & Eelen, 2003; Johnson, Greenhoot, Glisky & McCloskey, 2005; Meesters, Merckelbach, Muris & Wessel, 2000), suggesting that the association may only be revealed when using diagnostic measures of depressive symptoms and disorders.

There are very few studies in which AM characteristics in children have been described (Drummond, Dritschel, Astell, O’Carroll & Dalgleish, 2006; Orbach et al., 2001; Valentino, Toth & Cicchetti, 2009; Vrielynck, Deplus & Philippot, 2007). Drummond and colleagues (2006) reported greater overgeneral recall to positively valenced cue words in a non-referred sample of 14 dysphoric children (ages 7–11 years), compared with a healthy comparison group, after controlling for general scholastic ability. Their results also suggested that among the older children in the sample (10–11 year olds), dysphoria was associated with a greater likelihood of overgeneral memory retrieval to negative cues. Although the authors suggested that negative schemas, conceptualized as becoming more clearly defined and established with increasing age, may account for the greater influence of dysphoria on negative recall in older children, this interpretation is clearly limited by the small sample size. A second cross-sectional study compared three groups of children aged 9–13 years: children with a history of depression, children with a history of anxiety and/or behavioural disorders, and healthy controls (Vrielynck et al., 2007). The group with a history of depressive disorder generated fewer specific memories irrespective of cue valence compared with the other groups even after controlling for verbal IQ, and history of trauma. Further, current depressed mood did not mediate the effect of lifetime depression on overgeneral memory, providing some additional support for the notion that an overgeneral AM bias is a stable cognitive index of vulnerability to depression.

In addition to specificity or lack thereof, latency to respond to positive or negative cue words provides additional information about the accessibility of personal event recall. For example, clinically-referred adolescents demonstrated a longer latency to respond to positive cues than did non-referred adolescents (Swales et al., 2001). However, the association between latency to respond and clinical status has not been tested in children.

The lack of prospective research beginning in late childhood leaves open the question of whether an overgeneral memory bias is an early predictor of depression risk or is simply a characteristic of the depressive state. Identifying markers of vulnerability for depression during childhood and adolescence, prior to the onset of full threshold depressive disorder, could have a major public health impact and is critical for the development of effective prevention programs. The current study is a first step towards this goal. Identification of preadolescent risk factors is especially critical for girls, given evidence that girls’ risk for depression increases faster relative to boys in early adolescence (Angold, Costello & Worthman, 1998; Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer & Nelson, 1993; Kessler & Walters, 1998; Lewinsohn, Rohde & Seeley, 1998; Wade, Cairney & Pevalin, 2002), and that females carry a greater lifetime burden for depression than males (Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley & Andrews, 1993; Murray & Lopez, 1996; Weissman, Leaf & Holzer, 1984).

Prior work has shown that household poverty heightens an individual’s risk for depression (Gilman, Kawachi, Fitzmaurice & Buka, 2003; Leech, Larkby, Day & Day, 2006). Some studies also suggest that African American youth are more vulnerable to developing depressive disorder (Goldsmith, 2002; Sen, 2004; Van Voorhees, Paunesku, Kuwabara, Reinecke, & Basu, 2008), although this has not been shown consistently (e.g. Merikangas & Knight, 2009). Other research however has revealed significant racial/ethnic disparities in the course of depression and responsiveness to treatment. For example, compared with European Americans, African American individuals experience more chronic and impairing depressive disorders (Williams, D. et al., 2007), less complete functional and symptomatic recovery from treatment (Brown, Schulberg, Sacco, Perel & Houck, 1999), and African American children have been shown to benefit less from preventive interventions targeting negative cognitions (Cardemil, Reivich, Beevers, Seligman & James, 2007). These latter findings in particular, highlight the need for a better understanding of the interaction between race and the development of depression.

The primary goal of the current study was to examine the concurrent and prospective associations between the nature of autobiographical memory recall and symptoms of depression in an enriched community sample of young girls: half of whom were at heightened risk for the development of depression based on screening measures. In order to explore whether AM bias exists prior to the experience of a depressive disorder, as opposed to emerging as a consequence or ‘scar’ of having had a depressive episode, we focused on a developmental period that pre-dates the reported increase in female depression at around age 12–15 years of age (Angold et al., 1998; Lewinsohn et al., 1998; Rohde, Beevers, Stice & O’Neil, 2009). First, we hypothesized that overgeneral autobiographical recall at age 11 would predict level of depressive symptomatology in the following year, and that this predictive effect would hold even after accounting for sociodemographic factors and Verbal IQ. Based on the mixed findings in prior work with children and adolescents, no predictions were made as to whether the strength of this relationship varied by cue word valency. Second, we hypothesized that the level of depressive symptoms would be associated with a longer latency to generate an autobiographical memory, and that this would be more likely to occur in response to positive cue words. Finally, we conducted analyses to explore whether race moderated the association between AM and depression symptoms, based on prior evidence suggesting that vulnerability factors for depression operate differently for African American and European American children.

Method

Sample

Girls and their mothers were recruited from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS, N=2451), a prospective study of the development of psychopathology in girls. The PGS sample comprised girls aged 5–8 years old in the first assessment wave, who were recruited following an oversampling of the poorest city neighbourhoods (see Hipwell et al., 2002; Keenan et al., 2010 for more details). Girls were selected to participate in the Emotions sub-study (PGS-E) from the youngest participants in the PGS who either screened high on standardized measures of depressive symptoms by their self- and parent-report at age 8, or who were included in a random selection from the remaining girls (see Keenan, Hipwell, Feng, Babinski, Hinze, Rischall, & Henneberger, 2008). The measures used to enrich the sample for depressive symptoms and disorders later in development were the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold, Costello, Messer, Pickles, Winder, & Silver, 1995), and the Child Symptom Inventory (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1996). Girls whose scores fell at or above the 75th percentile by their own report, their mother’s report, or by both informants comprised the screen-high group (n = 135). There were significantly more African American than European American girls in this group. Girls selected from the remaining 75% of the PGS sample were matched to the screen-high group on race (n = 136). Of the 271 families eligible to participate, 232 (84.8%) agreed to participate and completed the first assessment when the girl was age 9 years.

Retention of girls in wave 3, when the assessment of AM was administered, and wave 4 of the study was high: 97.0% and 94.4% respectively. Comparison of depression symptom levels in waves 1, 2 and 3 between girls who were (N=13), and were not (N=219), lost to attrition in wave 4, was conducted to determine whether a bias resulting from attrition impacted the level of depression symptoms. Symptoms of depression did not differ between the two groups in any wave (ps <.05). Thirty-four girls with an estimated Verbal IQ at or below 70 were excluded from the current study due to the fact that the validity of the AM test has not been established for children with below average cognitive functioning. The final sample comprised 195 girls with complete data at wave 3 (mean age = 11.54 years, SD = .44) and at wave 4 (mean age = 12.53 years, SD = .45). Seventy percent of the girls were African American or Multi-racial. Approximately half of the families (50.5%) received public assistance (e.g., food stamps, Medicaid, or monies from public aid); receipt of public assistance was used as an index of family poverty. Less than half (40.2%) of parents had received 12 or fewer years of education, and 74% of the families were headed by a single parent.

Measures

Current symptoms of depression (i.e., past month) were measured using child reports on the Schedule for Affective Disorders for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL, Kaufman et al., 1997) in both laboratory visits conducted at ages 11 and 12. In this semi-structured diagnostic interview symptoms of depression are rigorously assessed by trained interviewers using standard probes to determine whether a behavior meets the symptom criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In the current study, all nine symptoms of depression were assessed regardless of whether disturbances in mood (i.e., sadness or irritability) or anhedonia were endorsed. In addition to using total number of symptoms endorsed (possible range 0–9), minor and major depressive disorders were generated from the K-SADS-PL according to DSM-IV criteria. Minor depression, a sub-syndromal form of major depression (MDD), was proposed as a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV. It is defined using the same duration criteria (2 weeks), the requirement of disturbance in mood (depressed mood or irritability) or anhedonia, and one additional symptom.

The K-SADS-PL has demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability for depression diagnoses, and significant associations with depression scales supporting good concurrent validity (Kaufman et al., 1997). In the current study, high levels of inter-rater reliability were achieved. A second trained interviewer listened to and coded responses (n = 42) from the digital video of the K-SADS-PL interview. The average intraclass correlation coefficient for total number of symptoms was .96, and the average kappa coefficient for minor/major depressive disorder was .89.

Overgeneral memory. The Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT) was administered to girls at age 11 to assess personal event memory (Williams & Broadbent, 1986). As part of the laboratory assessment, participants were asked to retrieve a specific personal memory to each of ten emotional cue words presented both orally and visually in a fixed order, alternating positive and negative cues (i.e. happy, bored, relieved, hopeless, excited, failure, lucky, lonely, relaxed, and sad). The girls’ responses were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The first response to each cue word was coded. An omission was recorded if a response was given 30 seconds after presentation. Participants who did not provide a specific memory as a first response were always given a standard prompt (“Can you think of a particular time – one particular event?”), even though their subsequent responses were not coded. First responses were rated as Specific (lasting a day or less, e.g. “when my uncle died”), or Overgeneral. Overgeneral responses included ‘extended’ memories (e.g. “when I was 12, we used to go bowling on Sundays”) or ‘categoric’ types (e.g. “when I’m at home with my mom”) following an established coding scheme (Williams & Dritschel, 1992). Inter-rater reliability for the classification of ratings of memories as Specific or Overgeneral was assessed on a random sample of 55 transcripts (550 responses) scored independently by two raters. Cohen’s kappa values ranged from 0.64 (excited) to 0.87 (lucky) for positive items and 0.71 (hopeless) to 0.79 (sad) for negative items. All Kappa values were significant at the 1% level. These reliability estimates were comparable to reliability rates found in the adult literature (e.g. Williams & Broadbent, 1986). Validity of the test was confirmed by the fact that none of the girls included in the final sample failed to retrieve a specific AM to at least one practice cue word.

Verbal IQ was estimated using the Vocabulary and Similarities subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III-R (Wechsler, 1991). These two subtests were administered by trained interviewers in the home when the girls were age 10 years as part of the PGS assessment battery. This short-form has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties relative to the full-length Verbal Scale (Donders, 1997; Kaufman, Kaufman, Balgopal & McLean, 1996).

Procedure

Approval for all study procedures was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent from the caregiver and verbal assent from the girl were obtained prior to data collection. The AMT and K-SADS were administered face-to-face with the girl in a private room in the research laboratory: the AMT in assessment wave 3, and the K-SADS-PL in waves 3 and 4. All the participants were financially reimbursed for their help with the study. Researchers coding the AMT responses were unaware of diagnostic status or depressive symptomatology of the girls.

Data Analysis Plan

The analyses were conducted in three stages. First, we examined the concurrent univariate associations between overgeneral AM and response latency with depressive symptomatology at age 11 using Spearman’s rho coefficient for non-parametric data. Second, we estimated Generalized Linear Models (GLM) to examine the main effects of the AMT indices (overgeneral memory bias and response latency irrespective of cue word valency) at age 11 on depressive symptoms reported at age 12. If either overgeneral bias or latency was significantly related to subsequent depressed mood, then the models were re-run for positive and negative cue words separately. In order to examine overgeneral AM as a predictor of subsequent depressive symptomatology at age 12, the level of depressive symptoms at age 11 were controlled for in all analyses. The potential moderating effects of race on the association between AM indices and depression symptoms were also tested in these models. Prior to computing interaction terms, the AMT variables were centered at the mean. In order to explore whether any effects of race were due to the greater representation of African American families living on low-incomes, receipt of public assistance was included in each model. A Poisson distribution was specified for the dependent measure of symptom counts and robust estimators of the standard errors. Finally, verbal IQ was added to the model to test whether the effects of AM style were accounted for by general cognitive impairment.

Results

Descriptive statistics

In the present study, the mean number of child-reported depressive symptoms in the sample was 1.22 (SD=1.53, median=1.0, range = 0–8), and 1.07 (SD=1.42, median = 1.0, range = 0–7,) at ages 11 and 12 years respectively. As expected, the distribution of depression symptoms was positively skewed (skewness = 1.49, s.e. of skewness = .17 at age 11 and skewness = 1.69, s.e. of skewness = .18 at age 12). Among 11-year-olds, 88 (45.1%) girls reported no symptoms, 45 (23.1%) reported one and 31.8% reported two or more. At age 12, 87 (46.3%) girls reported no symptoms, 52 (27.7%) reported one, and the remaining 26.1% reported two or more. The most commonly endorsed symptoms at both ages were changes in sleep, concentration, and appetite, and fatigue. Few girls met criteria for major or minor depression. At age 11, 3 girls met diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and 9 for minor depression, and at 12 years, 2 met diagnostic criteria for MDD and 10 for minor depression. Thus, twelve girls at 11 years and at 12 years (6.2% and 6.4% respectively) were diagnosed with either MDD or minor depression. Mean Verbal IQ for the final sample was 99.54 (SD=14.97, range = 76–148).

Descriptive statistics for AMT responses are shown in Table 1. On average, the girls generated 6.8 (SD=2.4) responses that were classified as specific, 1.56 (SD=1.87) as overgeneral-categoric and .45 (SD=.72) as overgeneral-extended. Out of 10 potential responses, a mean of 1.05 (SD=1.32) responses were coded as omissions. Because the reasons for scoring an omission were ambiguous (e.g. the girl may have been unable to retrieve a memory, or may have chosen not to report the memory), the proportion of overgeneral responses from classified responses was calculated and used in subsequent analyses. For the sample as a whole, 23.4% (SD=22.2) of classified responses were rated as overgeneral. Wilcoxon signed ranks test revealed that overgeneral responses were significantly more likely to occur in response to cue words that were negatively, rather than positively, valenced (z = 4.35, p<.001). Across all responses, the average latency to respond was 9.64 (SD=6.94) seconds. A significant effect of valence on latency to respond was observed, with a longer latency to negative than to positive cue words (Wilcoxon’s z = 6.65, p<.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of girls’ responses to the Autobiographical Memory Test.

| All cue words | Positive cue words | Negative cue words | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | range | Mean (SD) | range | Mean (SD) | range | |

| Specific | 6.83 (2.41) | 0–10 | 3.65 (1.34) | 0–5 | 3.18 (1.37) | 0–5 |

| Overgeneral | 2.01 (1.86) | 0–9 | .85 (1.06) | 0–5 | 1.16 (1.08) | 0–4 |

| - Categoric | 1.56 (1.87) | 0–9 | .68 (1.03) | 0–5 | .88 (1.07) | 0–4 |

| - Extended | .45 (.72) | 0–4 | .17 (.43) | 0–3 | .28 (.53) | 0–2 |

| Omission | 1.05 (1.32) | 0–6 | .45 (.74) | 0–5 | .61 (.85) | 0–4 |

| Proportion overgeneral | 2.34 (2.22) | 0–10 | .99 (1.21) | 0–5 | 1.39 (1.35) | 0–5 |

| Average latency | 9.64 (6.94) | 1.59–46.59 | 7.88 (5.59) | 1.15–36.17 | 12.27 (12.26) | 1.97–69.0 |

Comparison of AMT responses by race revealed no differences in the overall proportion of overgeneral memories produced by African American and European American girls. European American girls, however, demonstrated a longer response latency compared with African American girls (F [1,190] = 10.01, p <.01; mean latency = 11.97 sec, SD = 9.21, and mean = 8.60 sec, SD = 5.42, respectively). There were no differences in overgeneral memory bias or latency to respond to all cue words among girls living in family poverty compared with those who were not. Verbal IQ was significantly correlated with the overall proportion of overgeneral memories retrieved, such that high verbal IQ was associated with fewer overgeneral responses (r =−.16, p<.05). In addition, higher Verbal IQ was significantly correlated with longer response latency (r = .18, p<.05).

Univariate tests of the association between depressive symptoms and autobiographical memory

At age 11, girls’ responses on the AMT were concurrently associated with number of depressive symptoms. As shown in Table 2, significant correlations were revealed between depressed mood and overgeneral recall (Spearman’s rho = .16, p <.05), an effect that was accounted for by responses to positive cue words only (Spearman’s rho = .15, p <.05). Depressed mood was also related to a shorter latency to respond to AMT cues (Spearman’s rho =−.25, p<.001). In this case however, significant associations were revealed for both positively and negatively valenced words (Spearman’s rho =−.15, p< .05 and −.26, p < .001 respectively).

Table 2.

Concurrent associations between depression symptom counts and AMT responses at age 11.

| Depression symptom count | |

|---|---|

| r | |

| Race | .32** |

| Household poverty | .23** |

| IQ | −.29** |

| AMT response | |

| Proportion overgeneral | .16* |

| - positive cues | .15* |

| - negative cues | .13 |

| Average latency | −.25*** |

| - positive cues | −.15* |

| - negative cues | −.26*** |

Note: r = Spearman’s rho.

Multivariate tests of the prospective association between symptoms of depression and autobiographical memory

Generalized Linear Models were then conducted to examine the prospective associations between AMT response at age 11 years and depression symptoms at age 12 years, controlling for the effects of race, poverty, and depression symptoms at age 11. The interactions between race and overgeneral AM and latency, were also included as independent variables. As expected, depression symptoms at age 11 were strong predictors of depression symptoms at age 12 (B = .31, Wald χ2 = 76.57, p <.001). However, after accounting for this year-to-year stability, African American race (B = .74, Wald χ2 = 6.71, p =.01), overgeneral autobiographical recall (irrespective of cue word valency; B = .02, Wald χ2 = 11.52, p =.001), and the interaction between race and overgeneral recall (B =−.02, Wald χ2 = 6.57, p =.01) each predicted residual change in age 12 depression symptoms. The likelihood ratio chi-square for the overall model was χ2 [7] = 114.62, p < .001.

We then tested whether the same results held for both positive and negative cue words. The results showed that the association between overgeneral AM bias and change in depression symptoms was only evident for responses to positive, rather than negative, cue words (see Table 3). Thus, African American race, the proportion of overgeneral responses to positive cue words, and the interaction between overgeneral responses and race uniquely predicted depression symptoms in the following year, after controlling for depression symptoms at age 11. In contrast, the proportion of overgeneral responses to negative cue words was not associated with residual change in depression symptoms at age 12 (B = .008, Wald χ2 = 2.55, p = .110).

Table 3.

Prospective associations between overgeneral AM and response latency to positive and negative cues, and interactions between overgeneral AM recall and latency by race at age 11 and depressive symptom counts at age 12.

| 95% Wald (CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Lower | Upper | Wald χ2 | df | p |

| Response to positive cues | |||||||

| (Intercept) | −1.31 | .26 | −1.81 | −.81 | 26.18 | 1 | .000 |

| Age 11 depressive symptoms | .30 | .03 | .24 | .37 | 77.68 | 1 | .000 |

| Race | .80 | .30 | .21 | 1.39 | 7.13 | 1 | .008 |

| Household poverty | .27 | .17 | −.05 | .60 | 2.75 | 1 | ns |

| Overgeneral recall | .02 | .01 | .01 | .03 | 11.95 | 1 | .001 |

| Latency | −.01 | .03 | −.06 | .04 | .16 | 1 | ns |

| Overgeneral × race | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | 7.13 | 1 | .008 |

| Latency × race | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .05 | .30 | 1 | ns |

| Response to negative cues | |||||||

| (Intercept) | −1.18 | .23 | −1.62 | −.73 | 26.79 | 1 | .000 |

| Age 11 depressive symptoms | .31 | .03 | .24 | .38 | 80.06 | 1 | .000 |

| Race | .70 | .28 | .16 | 1.25 | 6.37 | 1 | .012 |

| Household poverty | .25 | .17 | −.07 | .58 | 2.34 | 1 | ns |

| Overgeneral recall | .01 | .00 | −.00 | .02 | 2.55 | 1 | ns |

| Latency | −.01 | .02 | −.04 | .03 | .20 | 1 | ns |

| Overgeneral × race | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | .00 | 1.87 | 1 | ns |

| Latency × race | −.01 | .02 | −.04 | .04 | .00 | 1 | ns |

Post hoc analyses were then conducted to test whether overgeneral AM bias to positive cues predicted the development vs. maintenance of depression symptoms between ages 11 and 12 (following Joiner, 1994). To achieve this, the age 11 overgeneral AM (for positive cues) by depression symptom interaction term was added to the previous model. The results showed no significant effect of this interaction term (B = − .001, Wald χ2 = .07, p = .79), and no change to the pattern of results shown in Table 3, indicating that the predictive utility of overgeneral AM (for positive cues) did not vary significantly as a function of initial depression symptom level.

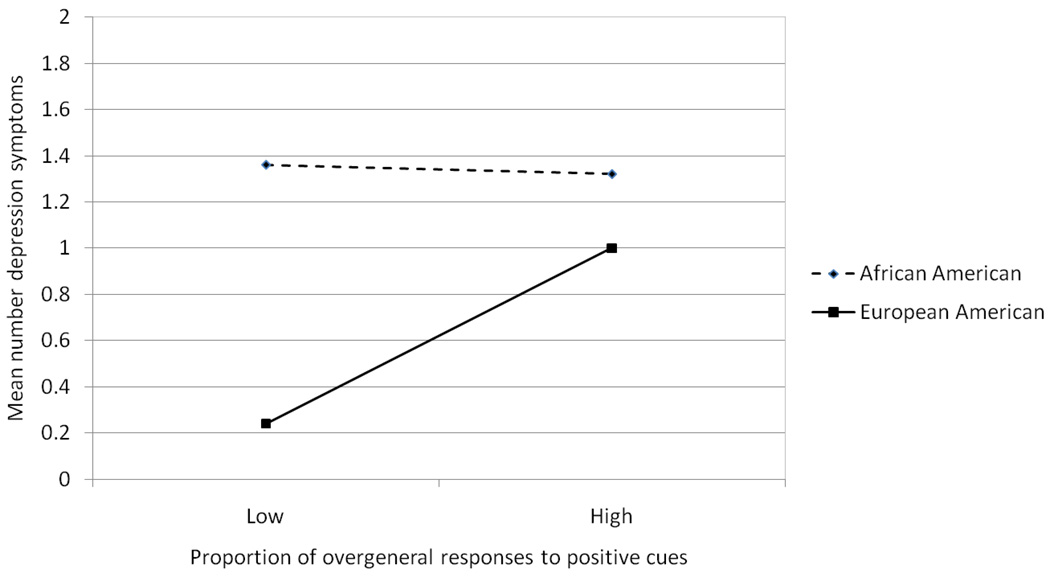

The moderating effect of race and overgeneral memory bias on subsequent depression symptoms was then probed by plotting the average number of depression symptoms for African American and European American girls with high (upper quartile) rates of overgeneral AM recall to positive cues versus all others. As shown in Figure 1, there was no difference in the number of depression symptoms between African American girls with lower rates of overgeneral recall (mean = 1.36 symptoms, SD=1.52) compared with high overgeneral recall (mean = 1.32 symptoms, SD=1.61) (t[121] = .11, p = n.s.). In contrast, European American girls with high overgeneral recall at age 11 had higher rates of depressive symptoms in the following year (mean = 1.00, SD=1.41) compared with European American girls demonstrating lower levels of overgeneral recall (mean = .24, SD=.54) (t [53] = −.2.90, p <.01).

Figure 1.

Interaction between race and overgeneral autobiographical memory at age 11 on depression symptoms at age 12.

In the final step, Verbal IQ and the interaction between Verbal IQ and race were added to the GLM model for responses to both positive and negative cues. The previous results were unchanged. Thus, Verbal IQ did not account for the significant effect of overgeneral autobiographical retrieval to positive cue words on depression symptoms in the following year.

Discussion

Results from the present study extend the existing literature on autobiographical memory and depression by examining overgeneral bias among young girls concurrently, and as a predictor of depression symptoms in the following year. The prospective design of the study, control for depression symptoms at time 1, as well as the focus on girls during a developmental period of known vulnerability for depression onset, were unique aspects of the current research.

The study findings demonstrated a small but significant concurrent association between overgeneral memory bias and young girls’ depressive symptoms. Consistent with results reported by Drummond and colleagues (2006), this relationship was evident for AM responses to positive, but not negative, cue words. In the prospective analyses, overgeneral recall to positive cues significantly predicted depression symptoms at age 12 after accounting for symptoms at age 11, race, family poverty, response latency and verbal IQ. These findings suggest that the relationship between overgeneral recall to positive cues and both concurrent and subsequent symptoms of depression is a robust one, revealed even in a non-referred sample of girls who have not yet reached the developmental period at highest risk for depression onset. The ability to detect an association between AM and early emerging depression symptoms is critical for generating testable hypotheses about the causal mechanisms related to onset of depressive disorders.

One hypothesis for the observed bias to positive, but not to negative cues, is that, by virtue of their young age, the girls had difficulty in processing negatively valenced material. For example, Drummond and colleagues (2005) reported that 6–11 year-old children were similar to adults in their ability to recognize happy and neutral faces, but were poorer at identifying negative affect. Indeed, the girls in the current study were generally slower to respond to negative than to positive cues, and as a group they were more likely to provide an overgeneral memory to negative than to positive cues. However this pattern was not observed in the relationship between AM recall and depression symptoms. Rather, the results suggest a particular significance of positive cues in the relationship between overgeneral AM retrieval and subsequent depressive symptoms, such that girls with emergent depressed mood may be less able to access positive events from their past. This hypothesis is consistent with prior work showing that children of depressed parents (i.e. at high risk for depression themselves) demonstrate impairments in memory for positive but not negative adjectives (Jaenicke, Hammen, Zupan, Hiroto, Gordon, Adrian, & Burge, 1987), as well as impaired processing of positive self-referent words following negative mood induction (Taylor & Ingram, 1999). Such deficits may trigger or exacerbate depression in several ways. For example, the individual may have difficulties in reflecting on past successes or prior examples of self-efficacious behavior, and thus lack a basis for generating solutions to new problems as they arise (Goddard et al., 1996). Alternatively, the individual may have difficulty in accessing positive memories to correct negative schemas that contribute to negative thinking and affect, or he/she may experience difficulties in imagining positive future outcomes (Williams et al., 1996).

The current findings also raise the possibility that a low level of positive emotionality is an important vulnerability trait for depression, as has been posited by Clark, Watson and Mineka (1994). In fact, prior research has shown that low levels of positive affect in children and adolescents do predict subsequent depressive symptoms and disorder (e.g. Lee & Rebok, 2002; Wilcox & Anthony, 2004), and that positive emotionality is related inversely to depressed mood in cross-sectional studies (Chorpita, Plummer & Moffitt, 2000; see also a review by Compas, Connor-Smith & Jaser, 2004). Positive emotions are also associated with more flexible attention and cognitive processes (Derryberry & Tucker, 1994; Fredrickson, 1998), which increases an individual’s capacity for integrating stimuli (Isen, 1990). An important goal for future research would be to determine whether overgeneral recall of positive autobiographical memories moderates and/or mediates the putative link between low temperamental positive affect and risk for depressive disorders among young adolescent girls.

An interesting finding of the current study was that young girls’ symptoms of depression were concurrently related to a shorter latency to respond to both positive and negative cue words. Moreover, there was no evidence that verbal fluency accounted for the relationship between depressed mood and overgeneral AM. These results suggest that the study findings cannot be accounted for by general cognitive lethargy that might be a characteristic of depression vulnerability. In contrast, recent data on depressed adults suggest that the overgeneral AM bias is indicative of poor task performance, possibly due to impaired executive control (Dalgleish et al., 2007). A possible explanation for these divergent findings is that the extent of depression is critical. The findings in the present study were for depression symptoms, not disorder, which may have not met the threshold required to impair functioning or task performance.

In addition to the main effect of overgeneral recall on depression symptoms in the following year, this predictive relationship was also moderated by race. Overgeneral recall to positive cues was more strongly associated with number of depression symptoms for European American than for African American girls. In fact, age 12 depression symptoms among African American girls appeared unrelated to AMT performance in the previous year. The reasons for this pattern of results are unclear. One possibility is that there is a threshold effect, such that, among children, the extent of overgeneral AM only distinguishes between vulnerabilities at lower levels of depression symptoms. As the mean level of depression symptoms was already higher among African American girls, other factors (e.g. family stress, neighbourhood disorder) may have been more salient predictors of depressed mood. Alternatively, this moderating effect of race may reflect different cultural experiences that reinforce or encourage rehearsal of memory for events. For example, the ways in which girls recall events from their past has been found to be related to the style of interaction that occurs between parents and their children (Nelson, 1993; Reese & Fivush, 1993). Research has shown that when mothers give precise information about past experiences, their children are better able to recall more specific memories (Reese & Fivush, 1993). It is therefore possible that differences in mother-daughter conversation content and style among African American and European American families might contribute to the group differences revealed here.

The current study is not without methodological limitations that may have affected the results and should be addressed in future research. First, it is important to recognize that what was modelled in the present study was low levels of symptoms of depression, and not depressive disorders. It is well established, however, that sub-threshold depression is associated with substantial functional impairment among adolescents (e.g., Gonzáles-Tejera et al., 2005), and significantly elevates the risk for developing full threshold depressive disorders (Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder & Beautrais, 2005; Klein, Shankman, Lewinsohn & Seeley, 2009; Pickles, Rowe, Simonoff, Foley, Rutter, & Silberg 2001; Pine, Cohen, Cohen & Brook, 1999). Furthermore, Keenan and colleagues (2008) reported that for each increase in number of depression symptoms at age 9, there was nearly a 2-fold increase in the risk of a later depressive disorder, and that over 78% of girls who met criteria for minor or major depression at ages 10 or 11 had at least 1 symptom at a younger age. The combined results of these studies suggest that there is significant morbidity associated with the depression symptoms observed in the current sample of preadolescent girls. Continued follow-up of the current sample will enable us to establish whether the results reported here also extend to the prediction of depression as a clinical entity. In addition, it will be important to establish whether an overgeneral AM bias can predict the course of depressive illness, as well as the probability of relapse and recurrence.

Second, we did not examine the extent to which the responses provided were ‘self-defining’ (Singer & Salovey, 1993), or truly autobiographical, versus insignificant events in the girls’ lives. It is possible that the relationship to depression varies along this dimension. Furthermore, we did not consider response perseveration (i.e. the same memory being provided for different cue words) when coding girls’ responses to the AMT cues. Such a pattern of response has been previously documented in a sample of clinic-referred adolescents who had experienced trauma (Swales et al., 2001).

An additional consideration in the current sample is the role played by comorbid conditions such as anxiety or externalizing problems. It is possible for example, that heightened vigilance or sub-threshold symptoms of anxiety may have led to shorter response latencies in girls also reporting symptoms of depression. A logical next step would be to examine whether the results reported here are specific to depression or reflect a more general vulnerability to other mental health problems.

Finally, exposure to trauma was not included in the current study. It is conceivable however, that there are distinct subgroups of girls at risk for depression: some girls may show overgeneral recall to negative cues associated with their experience of trauma, whereas for others, overgeneral recall may reflect a deficit with executive control as has been shown in some studies of adults (Dalgleish et al., 2007; Dalgleish, Rolfe, Golden, Dunn & Barnard, 2008). These hypothesized subgroups warrant further study to examine whether the relationships between overgeneral style and depression vary according to trauma experience. It is possible that such differences also contribute to the race effects observed here.

Implications for Research, Policy and Practice

The current sample was enriched for early depression symptoms and residence in low-income neighborhoods. Approximately 6% of the sample met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for major or minor depression: a rate that is 6–12 times that of other non-referred community samples of similar aged children (e.g., Anderson, Williams, McGee & Silva, 1987). The results, therefore, have implications for early detection of depression risk among urban dwelling preadolescent girls. As noted previously, low levels of depression symptoms manifest during the preadolescent period are stable and predictive of later depressive disorders (Keenan et al., 2008). Thus, establishing an association between autobiographical memory and emerging depression symptoms is of clinical relevance and provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that the nature AM recall predicts depression vulnerability. These results also suggest that girls who are at risk for depression could potentially be identified prior to adolescence, providing a critical opportunity to prevent a first episode of depressive disorder. The findings of the current study further suggest that cognitive interventions that improve specificity of AM recall as a means of preventing depression may be highly relevant during this developmental period. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy that aims to increase awareness of present experiences and reduce rumination, has been shown to increase AM specificity and reduce depressive symptoms in adults (Williams, Teasdale, Segal & Soulsby, 2000), but little is known about the efficacy of this approach in children.

Determining whether specific symptoms of depression account for the relationship with overgeneral memory to positive cues will be an important next step. For example, this finding may be largely driven by symptoms of anhedonia, i.e. a diminished capacity to experience enjoyment, or difficulties in activating, or sustaining positive emotions, rather than symptoms of depressed mood or irritability. The importance of these distinctions is becoming evident in research examining neuroaffective processes in depression. In particular, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown MDD-related neural dysfunction in responses to positive aspects of emotional stimuli. Atypical activity in amygdala, prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices, and striatum have been demonstrated in adults and adolescents with depressive disorders, compared to those without depression (Drevets, 2003; Epstein et al., 2006; Forbes, May, Siegle, Ladouceur, Ryan, Carter, & Dahl, 2006; Phillips, Drevets, Rauch, & Lane, 2003). For example, ventral striatal activation to pleasant visual stimuli is dampened among individuals with depression compared to those without depression (Lawrence, Williams, Surguladze, Brammer, Williams, & Phillips, 2004). Other work has shown that anhedonia is negatively associated with ventromedial prefrontal cortex and amygdala/ventral striatal activity, in response to positive stimuli (Keedwell, Andrew, Williams, Brammer, & Phillips, 2005). These emerging findings suggest that there may also be alterations in the neural systems of positive autobiographical memories relevant to depression. This, and the intriguing possibility that such alterations may be evident prior to depression onset, clearly warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xin Feng, and acknowledge the efforts of Danielle Aronson, Julia Chasler, Jess Edelstein, Alison Frazier, Brandon Gillie, Aerinne Owens, and Alison Ryan in coding responses to the Autobiographical Memory Task. Special thanks go to the families participating in the Learning About Girls’ Emotions Study.

Contributor Information

Alison E. Hipwell, Western Psychiatric Institute & Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Brenna Sapotichne, Western Psychiatric Institute & Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Susan Klostermann, Western Psychiatric Institute & Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Deena Battista, Western Psychiatric Institute & Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Kate Keenan, Department of Psychiatry, University of Chicago.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Williams S, McGee R, Silva PA. DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children: Prevalence in a large sample from the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:69–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800130081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman C. Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittlebank AD, Scott J, Williams JMG, Ferrier I. Autobiographical memory in depression: State or trait marker? British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;162:118–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Schulberg H, Sacco D, Perel J, Houck P. Effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary medical care practice: a post hoc analysis of outcomes for African American and white patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;53:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil E, Reivich K, Beevers C, Seligman M, James J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in low-income, minority children: Two-year follow-up. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45:313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, Plummer C, Moffitt C. Relations of tripartite dimensions of emotion to childhood anxiety and mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:299–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1005152505888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;100:316–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas B, Connor-Smith J, Jaser S. Temperament, stress reactivity and coping: Implications for depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:21–31. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Rolfe J, Golden A, Dunn BD, Barnard PJ. Reduced autobiographical memory specificity and posttraumatic stress: Exploring the contributions of impaired executive control and affect regulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:236–241. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Williams JMG, Golden AMJ, Perkins N, Barnard P, Au-Yeung C, Watkins E. Reduced specificity of autobiographical memory and depression: The role of executive processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2007;136:23–42. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Decker A, Hermans D, Raes F, Eelen P. Autobiographical memory specificity and trauma in inpatient adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:22–31. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Tucker D. Motivating the focus of attention. In: Neidenthal P, Kitayama S, editors. The heart’s eye: Emotional influences in perception and attention. San Diego, CA: Academic; 1994. pp. 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Donders J. A short form of the WISC-II for clinical use. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W. Neuroimaging abnormalities in the amygdala in mood disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;985:420–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond LE, Astell A, Dritschel B. Investigating development of over-general autobiographical memory following severe negative life events. A study of 11 to 16-year-olds in residential care; Paper presented at the Autobiographical Memory meeting, Morton College; Oxford, England: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond LE, Dritschel B, Astell A, O’Carroll RE, Dalgleish T. Effects of age, dysphoria, and emotion-focusing on autobiographical memory specificity in children. Cognition & Emotion. 2006;20:488–505. doi: 10.1080/02699930500341342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis J, Yang Y, Butler T, Chusid J, Silbersweig D. Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1784–1790. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D, Horwood L, Ridder E, Beautrais A. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E, May C, Siegle G, Ladouceur C, Ryan N, Carter C, Dahl R. Reward-related decision-making in pediatric major depressive disorder: An fMRI study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventory. Stony Brook, NY: State University of New York at Stony Brook; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Socio-economic status, family disruptions, and residential stability in childhood: Relation to onset, recurrence, and remission of major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1341–1355. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard L, Dritschel B, Burton A. Role of autobiographical memory in social problem-solving and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:609–616. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith S. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles-Tejera G, Canino G, Ramírez R, Chávez L, Shrout P, Bird H, Bauermeister J. Examining minor and major depression in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology. 2005;46:888–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D, Hargreaves I, Gregory S, Williams JMG. Autobiographical memory and emotion in a nonclinical sample of women with and without a reported history of childhood sexual abuse. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:129–142. doi: 10.1348/014466502163921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell A, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, Kroneman L. Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2002;12:99–118. doi: 10.1002/cbm.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen A. The influence of positive and negative affect on cognitive organization: Some implications for development. In: Stein N, Leventhal B, Trabasso T, editors. Psychological and biological approaches to emotion. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke C, Hammen C, Zupan B, Hiroto D, Gordon D, Adrian C, Burge D. Cognitive vulnerability in children at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:559–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00917241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Greenhoot A, Glisky E, McCloskey L. The relations among abuse, depression, and adolescents’ autobiographical memory. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:235–247. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Covariance of baseline symptom scores in prediction of future symptom scores: A methodological note. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1994;18:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Kaufman J, Balgopal R, McLean J. Comparison of three WISC-II short forms: Weighing psychometric, clinical and practical factors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children – present and lifetime version (KSADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell P, Andrew C, Williams S, Brammer M, Phillips M. The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Hipwell A, Chung T, Stepp S, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, McTigue K. The Pittsburgh Girls Study: Overview and initial findings. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:506–521. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Hipwell AE, Feng X, Babinski D, Hinze A, Rischall M, Henneberger A. Subthreshold symptoms of depression in preadolescent girls are stable and predictive of depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1433–1442. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181886eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Walters E. Epidemiology of DSM-II-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the national comorbidity survey. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7:3–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<3::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, McGonagle K, Swartz M, Blazer D, Nelson C. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Shankman S, Lewinsohn P, Seeley J. Subthreshold depressive disorder in adolescents: Predictors of escalation to full-syndrome depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:703–710. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a56606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Brewin C. Autobiographical memory functioning in depression and reports of early abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:585–591. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Dalgleish T. Autobiographical memory and depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;34:79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Howell R, Dalgleish T. Overgeneral autobiographical memory in depressed adolescents with, versus without, a reported history of trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:387–396. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence N, Williams A, Surguladze S, Brammer M, Williams S, Phillips ML. Subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Rebok G. Anxiety and depression in children: A test of the positive-negative affect model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:419–426. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech S, Larkby C, Day R, Day N. Predictors and correlations of high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among children at age 10. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:223–230. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000184930.18552.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Hops H, Roberts R, Seeley J, Andrews J. Adolescent psychopathology: Vol. 1 Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders among high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Rohde P, Seeley J. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinger H, Pachinger M, Leibetseder M, Fartacek R. Autobiographical memories in women remitted from major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:331–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally R, Lasko N, Macklin M, Pitman R. Autobiographical memory disturbance in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meesters C, Merckelbach H, Muris P, Wessel I. Autobiographical memory and trauma in adolescents. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Knight E. The epidemiology of depression in adolescents. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease. MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nandrino J, Pezard L, Poste A, Reveillere C, Beaune D. Autobiographical memory in major depression: A comparison between first-episode and recurrent patients. Psychopathology. 2002;35:335–340. doi: 10.1159/000068591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. The psychological and social origins of autobiographical memory. Psychological Science. 1993;4:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Orbach Y, Lamb ME, Sternberg KJ, Williams JMG, Dawud-Noursi S. The effect of being a victim or witness of family violence on the retrieval of autobiographical memories. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;25:1427–1437. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Goodyer IM, Teasdale JD. Categoric overgeneral autobiographical memory in adolescent with major depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:267–276. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701005189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M, Drevets W, Rauch S, Lane R. Neurobiology of Emotion Perception II: Implications for Major Psychiatric Disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:515–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Rowe R, Simonoff E, Foley D, Rutter M, Silberg J. Child psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial impairment: Relationship and prognostic significance. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:230–235. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine D, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: moodiness or mood disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:133–135. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Fivush R. Parental styles for talking about the past. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:596–606. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Beevers C, Stice E, O’Neil K. Major and minor depression in female adolescents: Onset, course, symptom presentation and demographic associations. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1339–1349. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2004;7:133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Salovey P, editors. The Remembered Self: Emotion and Memory in Personality. New York, NY: Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Swales MA, Williams JMG, Wood P. Specificity of autobiographical memory and mood disturbance in adolescents. Cognition & Emotion. 2001;15:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Ingram R. Cognitive reactivity and depressotypic information processing in children of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:202–208. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino K, Toth S, Cicchetti D. Autobiographical memory functioning among abused, neglected, and nonmaltreated children: The overgeneral memory effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1029–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees B, Paunesku D, Kuwabara S, Reinecke M, Basu A. Protective and vulnerability factors predicting new-onset depressive episode in a representative of U.S. adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vreeswijk MF, de Wilde EJ. Autobiographical memory specificity, psychopathology, depressed mood, and the use of the Autobiographical Memory Test: A meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:731–743. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrielynck N, Deplus S, Philippot P. Overgeneral autobiographical memory and depressive disorder in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:95–105. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade R, Cairney J, Pevalin D. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:190–198. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Holzer CE. The epidemiology of depression: An update on sex differences in rates. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1984;7:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(84)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox H, Anthony J. Child and adolescent clinical features as forerunners of adult-onset major depressive disorder: Retrospective evidence from an epidemiological sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Gonzalez H, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson J, Sweetman J, Jackson J. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG. Depression and the specificity of autobiographical memory. In: Rubin D, editor. Remembering Our Past: Studies in Autobiographical Memory. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 244–267. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Hermans D, Raes F, Watkins E, Dalgleish T. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:122–148. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Broadbent K. Autobiographical memory in attempted suicide patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:144–149. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Dritschel B. Emotional disturbance and the specificity of autobiographical memory. Cognition and Emotion. 1988;22:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Dritschel BH. Categoric and extended autobiographical memories. In: Conway M, Rubin D, Spencer H, Wagenaar W, editors. Theoretical Perspectives on Autobiographical Memory. London: Kluwer Academic; 1992. pp. 391–412. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Ellis N, Tyers C, Healy H, Rose G, Macleod AK. The specificity of autobiographical memory and imageability of the future. Memory and Cognition. 1996;24:116–125. doi: 10.3758/bf03197278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Teasdale J, Segal ZV, Soulsby J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:150–155. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Watts F, MacLeod C, Mathews A. Cognitive psychology and emotional disorders. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung CA, Dalgleish T, Golden A, Schartau P. Reduced specificity of autobiographical memories following a negative mood induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1481–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]