Abstract

Ultrasound is a relatively inexpensive, portable, and versatile imaging modality that has a broad range of clinical uses. It incorporates many imaging modes, such as conventional gray-scale “B-mode” imaging to display echo amplitude in a scanned plane; M-mode imaging to track motion at a given fixed location over time; duplex, color, and power Doppler imaging to display motion in a scanned plane; harmonic imaging to display non-linear responses to incident ultrasound; elastographic imaging to display relative tissue stiffness; and contrast-agent imaging with simple contrast agents to display blood-filled spaces or with targeted agents to display specific agent-binding tissue types. These imaging modes have been well described in the scientific, engineering, and clinical literature. A less well-known ultrasonic imaging technology is based on quantitative ultrasound or (QUS), which analyzes the distribution of power as a function of frequency in the original received echo signals from tissue and exploits the resulting spectral parameters to characterize and distinguish among tissues. This article discusses the attributes of QUS-based methods for imaging cancers and providing improved means of detecting and assessing tumors. The discussion will include applications to imaging primary prostate cancer and metastatic cancer in lymph nodes to illustrate the methods.

Ultrasound has become a very commonly used clinical imaging modality because it is relatively inexpensive, portable, and versatile; it is an imaging modality that has found widespread acceptance in a broad range of applications ranging from screening through biopsy guidance to treatment targeting and therapy monitoring. Clinical applications of ultrasound incorporate many imaging modes, such as conventional gray-scale “B-mode” imaging to display echo amplitude in a scanned plane; M-mode imaging to track motion at a given fixed location over time; duplex, color, and power Doppler imaging to display motion in a scanned plane; harmonic imaging to display non-linear responses to incident ultrasound; elastographic imaging to display relative tissue stiffness; and contrast-agent imaging with simple contrast agents to display blood-filled spaces or with targeted agents to display specific agent-binding tissue types. These imaging modes have been well described in the scientific, engineering, and clinical literature over the past several decades.1–9 A less well-known ultrasonic imaging technology is based on quantitative ultrasound or (QUS), which analyzes the distribution of power as a function of frequency in the received echo signals backscattered from tissue; QUS exploits the resulting spectral parameters to characterize and distinguish among tissues.

The ultrasonic spectrum-analysis methods underlying QUS have been evolving since the early 1970s and were first described in terms of a theoretical frame-work for weak scattering from soft tissue by Lizzi and colleagues in the 1980s.10–12 The Lizzi framework was extended by Insana and others in the 1990s and currently is being further refined and applied by several investigators who have popularized the term QUS.13–18

The key premise underlying QUS is that the original received echo signals, also termed radiofrequency (RF) signals, contain more information than the envelope-detected signals that display echo amplitude on a video monitor, eg, in a conventional gray-scale, B-mode image. Associated premises are that a substantial part of that additional information can be extracted from the frequency content of the RF signals using spectrum analysis, and that parameters associated with the spectra computed from these signals can discriminate among different types or states of tissue. Furthermore, the theoretical frameworks for scattering from soft tissue relate spectral-parameter values to effective scatterer properties such as effective size and “acoustic concentration,” which is the product of the number concentration of the scatterers and the square of their impedance relative to their surrounding medium.

This article discusses the attributes of QUS-based methods for imaging cancers and providing improved means of detecting and assessing tumors. The discussion illustrates the methods by describing current studies imaging primary prostate cancer and metastatic cancer in lymph nodes.

PRINCIPLES OF QUS

QUS seeks to exploit the additional information that exists in the RF echo signals backscattered from tissue to characterize scattering behavior of tissues quantitatively, and in many applications, to estimate the properties of the scatterers that give rise to the echo signals. In the simplest applications, distinctions among tissue types (eg, cancerous ν noncancerous) or among tissue states (eg, responsive to treatment ν unresponsive or aggressively growing ν dormant) are made based on simple parameters computed from the echo signals. In more advanced applications, scatterer properties, such as effective scatterer size or the product of effective scatterer concentration and the acoustic concentration, are estimated using sophisticated scattering models. Both types of applications utilize spectrum analysis of the original echo signals. 10–14 Spectrum analysis is performed before any nonlinear processing such as signal compression or envelope detection is applied and before any of the information carried by the RF signals is lost in the process of conventional, gray-scale image formation.

First, RF data are digitized and stored from a set of scan planes of interest. This set of planes can consist of largely independent separate planes or the set may constitute a group of spatially related planes that comprise a volume. Second, a region of interest (ROI) is defined that can comprise the entirety or simply a portion of each scan plane. Windows then are applied to the RF signals comprising each scan vector within the ROI; these typically are “sliding” windows that select RF data for analysis in a series of small steps, eg, steps of 8 samples for a window that is 64 samples wide. These windows usually are smoothly varying functions that resemble cosine or squared-cosine functions. Third, spectrum analysis is performed at each window location, and in some cases, scatterer properties are estimated using parameters derived from a power spectrum, as summarized below.

Calibrated, ie, system-corrected, power spectra are the basis of tissue typing and tissue-property estimation in QUS. Power spectra are computed as the squared magnitude of the Fourier transform of the windowed RF signals. However, the spectra of echo signals derived from tissue are affected by the properties of the system, ie, the transducer and the pulsing and receiving electronics, as well as by the properties of the tissue. To remove the contributions of the system, calibration, which sometimes is termed normalization, is required. Calibration uses echo signals from a well-understood target to determine the contributions of the system. In the case of a single-element transducer, the calibration target is a well defined planar reflector, such as a “perfectly” reflecting glass or metal plate or such as a weakly reflecting water-oil interface, that is placed in the ultrasound beam with its surface in the center of the focal zone and its orientation exactly perpendicular to the beam axis, ie, parallel to the planar wave fronts that exist at the focus. The difference between the uncalibrated tissue spectrum and the calibration spectrum represents the contribution of the tissue alone to the received-signal spectrum. In the case of an array transducer, a target scattering that is well specified in terms of scatterer size, scatterer and medium impedances, and scatterer concentration is used and the spectrum of the RF echo signals from the target is compared to the theoretically predicted spectrum19; the difference between the empirical and predicted spectra corresponds to the contribution of the system, and tissue spectra then are corrected accordingly. Calibrated power-spectrum amplitudes are expressed as decibels relative to the corresponding spectrum of a perfect reflector. (In some publications, the units of calibrated power-spectrum amplitude are termed “dBr” because they represent relative values in decibels.)

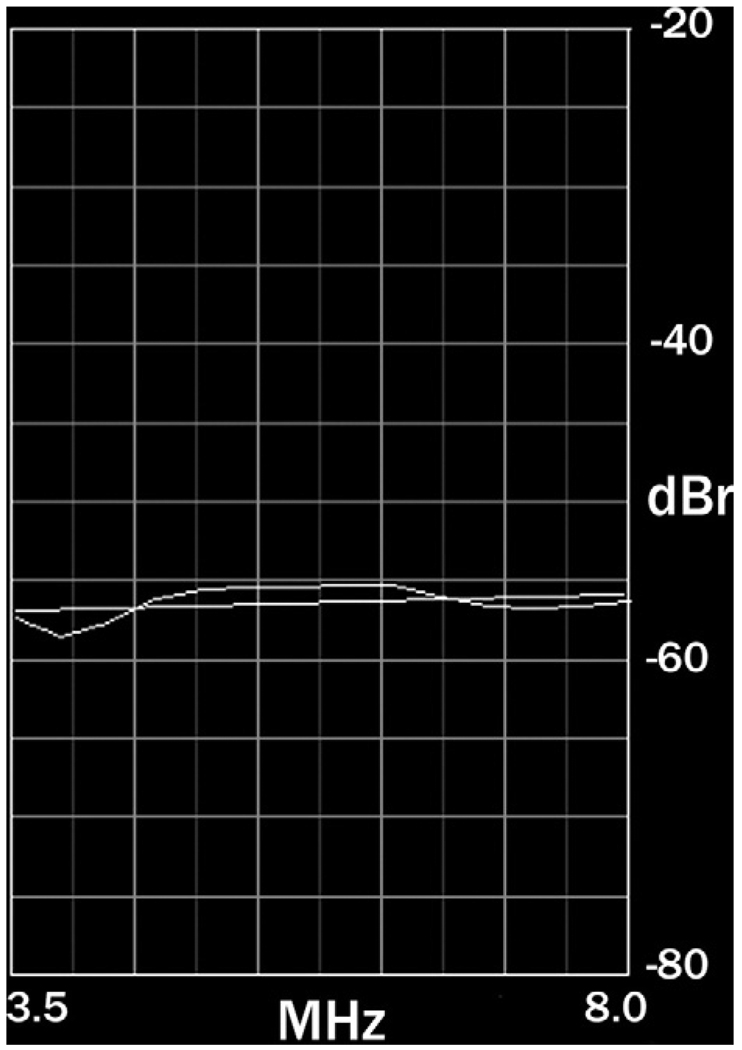

According to the theory developed by Lizzi et al and subsequently extended by Insana et al, calibrated power spectra plot backscattered power versus frequency as a gently curved line over the usable frequency band of the echo signals, as shown in Figure 1 for the spectrum of echo signals from a prostate gland over a frequency range of 3.5 to 8.0 MHz.10–14,20–25 As the number of independent windowed RF regions increases and more spectra are averaged, statistical stability in the spectral estimate improves, and the spectrum more closely resembles a smooth curve. Typically, this curve is approximated by a straight line. The parameters of this straight line that are used in QUS are the slope, intercept, and midband values. Based on the theoretical framework for spectrum analysis, the slope value depends solely on scatterer size but is depressed by frequency-dependent attenuation effects; the intercept value theoretically is independent of attenuation (assuming attenuation is linearly dependent on the first power of frequency); the midband value depends on attenuation-dependent slope as well as attenuation-independent intercept—therefore, the midband value also is dependent on attenuation.

Figure 1.

A typical normalized spectrum. The example shows a spectrum of prostate tissue echoes over the frequency range of 3.5 to 8.0 MHz. The spectrum is approximated by a straight line.

QUS can stop at the point of computing the values of spectral parameters and can distinguish among tissue types, eg, between diseased and disease-free tissue, based solely on empirically determined differences in their respective parameter values. Furthermore, images can be generated in two dimensions (2D) or three dimensions (3D) that depict tissue types at each pixel based on the parameter values computed at the spatially matching location in the image plane. Alternatively, QUS also can estimate scatterer properties from spectral-parameter estimates. Estimates of scatterer size are based on the theoretical relationship between size and attenuation-free or attenuation-corrected slope values; estimates of the product of scatterer concentration and the square of relative acoustic impedance, also termed acoustic concentration, are based on intercept values, which are a function of scatterer size and acoustic concentration. The slope value increases with decreasing scatterer size down to a size that is a fraction of the ultrasound wavelength, then it remains fixed; the intercept value increases with increasing scatterer size and increasing acoustic concentration. See the cited literature for greater detail.10–14

PROSTATE STUDIES

Prostate cancer currently is detected using ultrasound-guided needle biopsies. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) is able to define prostate anatomy, ie, prostate borders and internal regions, but it cannot reliably depict cancerous foci in the gland. Therefore, biopsy needles are directed into the gland simply with respect to gland regions, such as the left and right base, mid, and apex, but blindly with respect to occult tumor foci that may be present. In early stages of disease, when cancerous foci are small and widely separated, but easily treatable, biopsy needles frequently miss existing lesions and consequently result in false-negative determinations. Similarly, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and other current, clinical, imaging modalities are ineffective in depicting cancers of the prostate, even though many of them can show the prostate itself with excellent definition.26 As a consequence, current imaging methods cannot reliably provide information that is essential for effectively guiding biopsies, planning treatment, and monitoring treated or “watched” cancers.

Our analyses of repeat-biopsy data showed that the sensitivity of current TRUS-guided procedures may be as poor as 50%; therefore, perhaps half of the actual cancers presenting for biopsy may be missed.21 Our recent results confirm previously published results20–25; they suggest that significant (eg, 50%) improvements in sensitivity may be possible using ultrasonic tissue-type images (TTIs) to guide biopsies. Similarly, improvements in outcomes and reduced deleterious side effects may be achieved if TTIs can show cancerous and, equally important, noncancerous regions with higher confidence than current imaging methods provide. For example, imaging that reliably shows cancer-free regions of the prostate possibly could improve outcomes in nerve-sparing surgical treatments and minimize damage to the rectum, bladder, and urethra in radiation treatments.

The research summarized here seeks to develop TTI methods capable of reliably identifying and characterizing cancerous prostate tissue and thereby able to improve the effectiveness of biopsy guidance, therapy targeting, and treatment monitoring. While this research utilizes nonlinear classifiers such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) to characterize prostate tissue based on spectrum-analysis parameters and clinical variables such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), age, and race, we recognize that other ultrasonic methods and also other imaging modalities can provide additional, independent information that potentially could be combined with ultrasonic spectrum analysis in TTIs to markedly improve the efficacy of TTIs in depicting prostate cancer. The ultrasonic methods that offer potential important information for classification include perfusion imaging that uses ultrasonic contrast agents to assess normal and abnormal vasculature and elasticity imaging to depict relatively stiff regions of the gland. In addition, magnetic resonance methods offer some exciting possibilities for sensing local chemical changes associated with prostate cancer. We also note that investigations by Scheipers et al and others20–27 applied multifeature approaches to characterizing prostate cancer; their methods emphasized analysis of texture features in B-mode ultrasonic images, but they also employed spectrum analyses of RF data and confirmed successful application of ultrasonic spectral parameters in ANN-based classification methods.

Methods

In collaboration with several medical centers (including the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, DC, and the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, WA), we have been acquiring RF echo-signal data and clinical variables, including PSA, during biopsy examinations of the prostate. We computed the power spectra of RF signals site-matched to each biopsy region and trained ANNs with more than 3,500 sets of ultrasonic, clinical, and histological data acquired since the inception of our study. Intercept and midband spectral parameters were computed in accordance with the theoretical framework of Lizzi et al.10–12 In every analyzed case, biopsy histology results served as the gold standard for training and evaluating classifiers. The findings described here are derived from data obtained at the Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Data Acquisition

RF data were acquired during TRUS-guided biopsy examinations by digitizing the RF echo signals accessed within a Hitachi (Twinsburg, OH) EUB 525 scanner using a EUP V53W end-fire curved-array probe with a nominal center frequency of 7.5 MHz. Digitization was performed by a GaGe (Lashine, QC, Canada) Compuscope 1250-1M data-acquisition board sampling at a rate of 50 MS/s. Each scan plane consisted of 155 digitized scan vectors and each vector included 3,600, 12-bit samples.

Clinical data, such as the value of each patient’s PSA level, age, race, and ethnicity, were entered into the RF data-file header. A key entry was the level of suspicion (LOS) for cancer assigned to the biopsied region of each scan by the examining urologist. This LOS assignment was based on the appearance of the conventional B-mode image at the biopsy site combined with any other information available to the urologist, eg, PSA value or results of the patient’s digital rectal examination (rectal palpation). The LOS served as our essential baseline for assessing the relative performance of our classification methods. The gold standard for determining actual tissue type was the pathology report based on biopsy histology. The institutional review board of the Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved the human subject protocols employed in this research.

Patient Recruitment

Patients for the study described here were recruited from the pool of patients undergoing biopsy at the Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Our latest dataset consisted of ultrasonic, clinical and histology data from 617 biopsies administered to 64 patients; the racial composition of this patient population was predominantly Black of African descent. (In comparison, our earlier results were based on a predominantly Caucasian patient population. 20–25) Cancer was detected by the biopsies in 23 (35.9%) of these 64 patients and in 103 (16.7%) of the 617 biopsy cores. The incidence of positive biopsies and the fraction of patients with detected cancer were slightly higher in this dataset than we typically find in our studies. For example, in our prior data sets, the incidence of positive biopsies tended to be close to 30% and the fraction of patients with detected cancers tended to be between 10% and 11%.20–25

Data Analysis and Maintenance

RF echo-signal data were analyzed using the methods described by Lizzi and co-workers.10–12 Custom software was developed using LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX). This software computed spectral-parameter values over the entire digitized scan using the methods described above. Spectra were computed over an effective frequency range of 3.5 to 8.0 MHz at every window position along each of the 155 vectors in the digitized scan. (Actual tissue spectra showed that the signal-to-noise ratio [SNR] was consistently adequate over the frequency band extending from 3.5 MHz to 8.0 MHz.) The slope and intercept values were computed, and at each window location, slope was corrected for an assumed attenuation of 0.5 dB/MHz-cm.

The average values of slope, intercept, and midband parameters were computed over an ROI site matched to the biopsy region. As a consequence, spectral-parameter values could be exactly associated with corresponding spatially co-registered histological determinations.

Tissue Classification

As described in previous publications, our classification studies used standard and custom software for implementing ANN configurations with multilayer perceptrons and radial-basis functions.20, 22, 24, 25 The inputs for the ANNs were intercept value, midband value, and PSA value, with biopsy results serving as the gold standard for true tissue type. We used MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) to classify spectral-parameter values and PSA for biopsy-proven prostate tissues. Our classification efforts sought only to segregate cancerous from noncancerous peripheral zone tissue from the prostate. However, the sampled tissue included a wide range of cancerous tissues, eg, degrees of differentiation and aggressiveness as estimated histologically from the biopsy specimens, and numerous noncancerous types of diseased or unhealthy prostate tissue, eg, inflammatory conditions, benign hyperplasia, atrophy, etc.

We implemented a multilayer-perceptron ANN with MATLAB. We used a custom script to limit the test set to a single patient and to place all the biopsies for that patient in the test set; all other data were assigned to the training and validation sets with 90% of those data in the training set and 10% in the validation set. A separate MATLAB run was performed for each patient; accordingly, we termed this a “leave-one-patient-out” approach. We varied the network parameters to determine empirically the most effective ANN configuration by varying the number of hidden layers, number of nodes in each layer, activation functions, learning rates, etc.

Recently, we have been applying more robust support-vector machines (SVMs) to this classification problem using these same data sets, and our results with SVMs are equivalent to those obtained with ANNs.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Analyses

For evaluation purposes, the scores of all 64 runs of each ANN configuration were merged into a single dataset and analyzed as a whole. The 64, single-patient runs had eight to 12 usable biopsies for each patient and so had 10 to 12 biopsies in each test set; the 64 sets of scores were combined into a single set of 617 scores for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) evaluation.

As mentioned earlier, our baseline for evaluating the improved classification provided by our methods was the LOS for cancer that was determined by the examining urologist using the B-mode appearance of the biopsy site combined with other available clinical information (eg, PSA level, rectal-palpation impressions, etc.) To assess the relative tissue-typing efficacy of the ANN classifier, we compared its classification performance to the LOS representing conventional classification using ROC analyses.28

To compute ROC curves and the areas under the curves (AUCs), we used software offered by various authors (eg, ROCkit by C. Metz of the University of Chicago, and MedCalc by F. Schoonjans, University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium). These software packages provide AUC estimates, standard errors in AUC estimates, 95% confidence intervals for AUC estimates, and statistics regarding the likelihood that two ROC curves are in fact different. As discussed below, we have found that differences in AUC estimates so greatly exceed the sum of the standard errors in those estimates that ample confidence exists that the performance of the ANN classifier is significantly superior to conventional methods as assessed using the B-mode-based LOS.

Lookup Tables

We generated lookup tables (LUTs) for translating spectral-parameter and clinical variables to a relative likelihood for cancer using the optimal MATLAB multi-layer perceptron configuration, ie, the combination of layers, nodes, etc, that gave the best AUCs. The LUT reduces computational time in generating TTIs by eliminating the need to run an ANN analysis in order to compute a score for cancer relative likelihood at every image pixel. Instead, when using an LUT, spectral-parameter values are computed at each pixel location and the computed parameter values along with the patient’s PSA level are referred to the LUT, which then returns a cancer-likelihood score. Software for gray-scale imaging then translates the “raw” score into a pixel value, eg, a value of 0 for the lowest score in the set of raw scores to 255 for the highest score. The software also can present different score ranges as false colors to indicate different ranges in cancer likelihood; for example, red above a certain threshold to indicate the greatest likelihood of cancer, orange between two thresholds to indicate a somewhat lesser likelihood, and on down to green to indicate a minimal likelihood. We routinely use five colors ranging from green through yellow-green, yellow, orange, and red overlaid on a midband image; alternatively, we use just orange and red to show regions of highest suspicion. The former false-color scheme might be used for guiding biopsies, while the latter might be used for targeting radiation. This procedure is performed on a pixel-by-pixel basis either over the entire scan or over a user-specified subregion of the scan. An example of a small subregion might be a limited biopsy area for use in validating TTI performance by comparison with actual biopsy data or a somewhat larger sector window for use in guiding biopsies.

To date, we have used 40 × 40 × 40, 64,000-element LUTs consisting of 40 values of the midband parameter, 40 values of the intercept parameter, and 40 values of PSA. Values were selected to correspond to the predominant ranges of actual values in the data, eg, −65 to −35 dB for intercept, −65 to −47 dB for midband, and 0 to 39 or 78 ng/ml for PSA. For all three variables, values were linearly incremented over these ranges; eg, for PSA, the 40 values were incremented uniformly by 1 for a value range of 0 to 39 or by 2 for a value range of 0 to 78.

Results

The ROC-curve AUCs for this data set were greater for neural network-based classification than for the B-mode-based LOS classification by more 32%, and the small standard errors compared to the area differences confirm that the AUC differences are statistically significant. For the 64 patients with 617 biopsy specimens, our MATLAB multilayer perceptron area was 0.844 ± 0.018. In comparison, the LOS-based curve area was only 0.638 ± 0.031. Furthermore, the AUC 95% confidence interval for the neural network-based classifier was 0.806 to 0.877, whereas the interval for the LOS-based curve was 0.576 to 0.697. The SVM-based AUC was comparable, but slightly higher.

Using the same data and applying more-robust SVM methods for classification, the ROC AUC was 0.850 ± 0.024. This classifier performance essentially is identical to the previously obtained ANN performance.

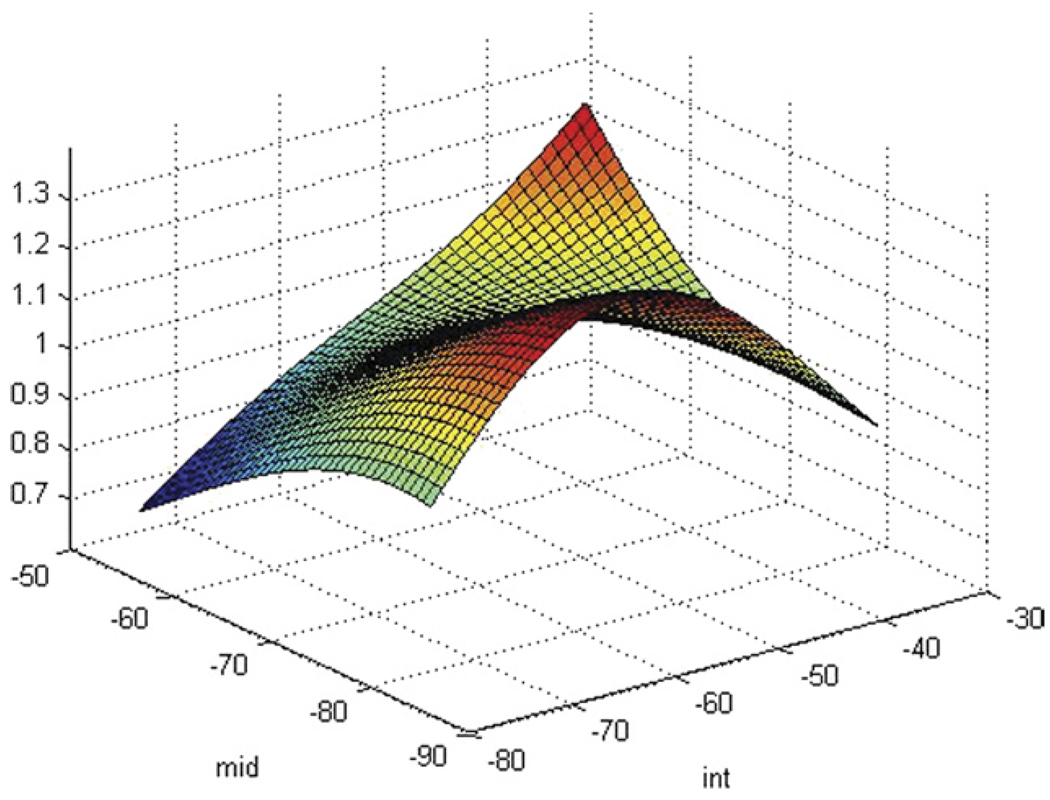

As indicated earlier, we generated LUTs to translate spectral-parameter and PSA values directly to pixel values. An example of a LUT generated from an SVM classifier is shown in Figure 2, which depicts the LUT for a serum PSA level of 8 ng/ml. The vertical axis in Figure 2 corresponds to the cancer-likelihood score; the horizontal axis on the lower left corresponds to midband value decreasing from left to right left; and the horizontal axis on the lower right corresponds to intercept value increasing from bottom to top, ie, the lowest spectral-parameter values are at the nearest corner of the bottom plane and the highest values are at the farthest corner. Figure 2 displays the LUT only for PSA 8, but the distribution of scores is markedly dependent on the PSA values. At low PSA levels, eg, lower than 4 ng/ml, LUT cancer-likelihood scores are relatively uniformly low with a slight peak at low midband and intermediate intercept values; at low to moderate PSA levels, eg, between 4 and 10 ng/ml, LUT scores elevate generally, and higher LUT scores are apparent at low midband values and intermediate intercept values; at higher PSA levels, eg, above 15 ng/ml, peak LUT scores shift to higher spectral-parameter values and the surface contour becomes flatter. As PSA levels increase further, this trend continues. In Figure 2, the elevated LUT amplitude at high intercept and midband values are artifactual; they result from a paucity of actual data corresponding to the highest artificial parameter values. A similar paucity exists at the lowest artificial parameter values.

Figure 2.

SVM-based LUT for PSA 8 over the common range of intercepts and midband values for prostate tissue. The vertical axis is relative cancer likelihood, which is maximal at low midband and intermediate intercept values.

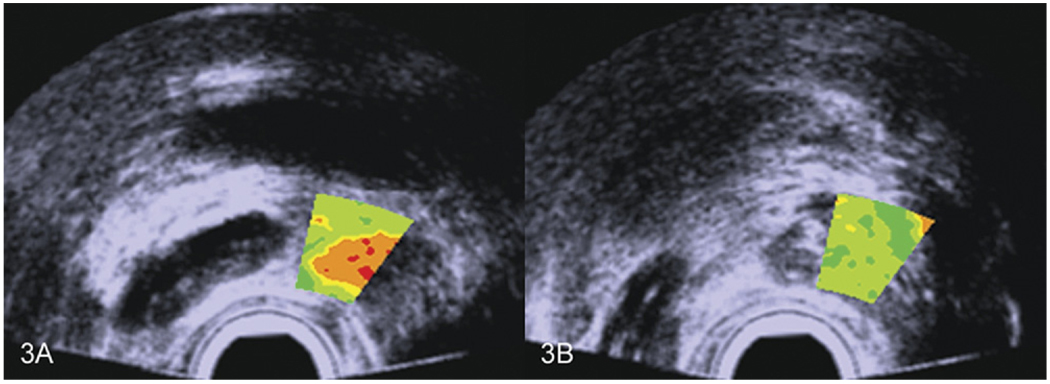

In biopsy guidance, larger TTI windows spanning the general location where biopsy sampling occurs could be used, and in treatment planning, the TTI might apply to the entire scan. Examples of larger TTI biopsy-guidance windows are shown in Figure 3 for two different biopsy locations in the same patient; Figure 3A shows the plane in which a cancerous biopsy was obtained, while Figure 3B shows the plane in which a noncancerous biopsy was obtained. If such TTIs had been available to the urologist at the time of the actual biopsy, better guidance of the needle into cancerous regions and avoidance of noncancerous regions would have been possible.

Figure 3.

Small biopsy-guiding ROI overlays indicating high and low suspicion of cancer in the same prostate gland. Red indicates the highest likelihood; green indicates the lowest likelihood. Colors are consistent with the actual subsequent biopsy results.

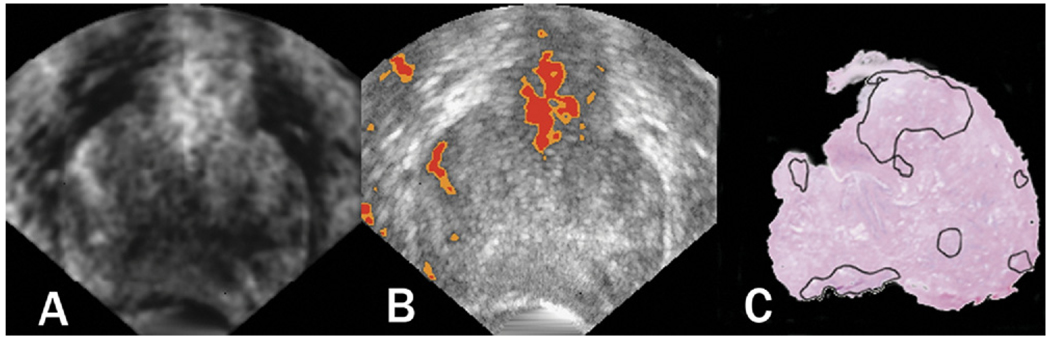

Figure 4 shows transverse-plane 2D TTIs and equivalent whole-mount prostatectomy histology of a prostate that was scanned prior to surgery and subsequently was determined to contain a previously undetected 12-mm anterior tumor. Although the histology and scan planes cannot be assumed to be exactly spatially matched, they both occurred at the greatest gland diameter and show an encouraging match between the demarcated histologically determined cancer foci (along with some precancerous regions near the colon) and the TTI-depicted high-suspicion regions. The left image is a gray-scale TTI; the center image is a midband-value depiction with a color-encoded overlay showing only the highest levels of suspicion; the right image is whole-mount histology with cancerous and precancerous regions demarcated by the pathologist. A corresponding 3D rendering is shown in Figure 5; the perspective is reversed in Figure 5 compared to Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Transverse-plane 2D TTIs and whole-mount prostatectomy histology of a prostate. The left image is a gray-scale TTI; the center image is a midband-value depiction with a color-encoded overlay showing only the highest levels of suspicion; the right image is whole-mount histology with cancerous and pre-cancerous regions demarcated by the pathologist. The gland was scanned prior to surgery and subsequently was determined to contain a previously undetected 12-mm anterior tumor.

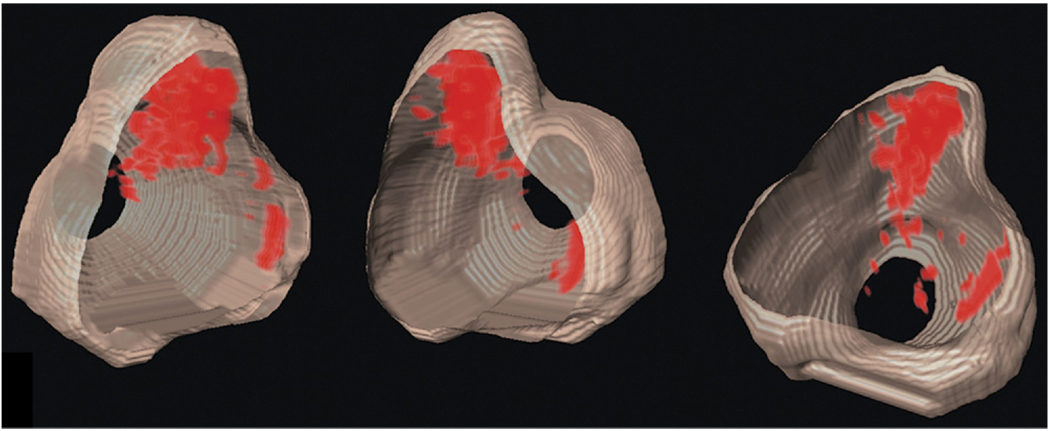

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional depictions of the gland shown in Figure 4. The perspective is reversed versus Figure 4.

Discussion and Conclusions

Current results match previous results from a different medical center and patient demographics.20–25 The ROC AUC estimate is more than 30% greater for ANN and SVM classification than for conventional imaging combined with clinical information, and the standard errors for the AUC estimates are sufficiently small to assure that the area differences are significant. The implication of these ROC differences is a potential improvement in biopsy sensitivity of more than 50%, ie, false-negative biopsies could be markedly reduced by using TTIs to guide biopsies, and the cost and anxiety of commonly required repeat biopsies in the face of rising PSA levels with no histological verification of cancer could be mitigated. Similarly, TTIs could be used to plan and target treatment and potentially would make focal therapy of prostate cancer an accepted clinical option.

In summary, TTIs show very encouraging promise for improving the detection and management of prostate cancer, including for guiding biopsies, delivering focal therapy, and assessing the effects of treatment.

LYMPH NODE STUDIES

Reliably determining whether lymph nodes contain metastases from a primary tumor is essential for staging the disease and selecting optimal treatment. Unfortunately, the methods available for detecting nodal metastases easily can overlook small but clinically significant metastases in the size range extending from 0.2 to 2.0 mm. Currently, lymph nodes dissected from a cancer patient either are sent to pathology for a complete postoperative histologic preparation and evaluation, or they undergo an intraoperative “touch-prep” procedure, such as in the case of sentinel node procedures for breast cancer. The touch-prep procedure used for sentinel nodes is intended to detect nodal metastases immediately, ie, while the patient remains under anesthesia in the operating room. If metastases are detected in a touch-prepped node, then a formal (ie, complete) node dissection is performed during the same operation. In the touch-prep procedure, each dissected node is cut in half with a scalpel and both cut surfaces are pressed on a microscope slide to transfer cells to the slide for cytological microscopic examination. Neither a formal lymphadenectomy nor a sentinel procedure is able to detect small nodal metastases reliably, particularly micrometastases smaller than 2.0 mm. The touch-prep approach suffers from a particularly large number of false-negative determinations because the pathologist only examines cells from two adjacent surfaces of the lymph node and the cells derived from these surfaces may not reveal the presence of a small cancerous region within a metastatic node.

Postoperatively, all dissected nodes (including touch-prepped nodes) undergo a complete histologic evaluation that involves thick-sectioning into blocks (2- to 3-mm thick), fixation and embedding, thin-sectioning of the surfaces of the thick sections, placement of thin sections (3- to 4-mm thick) on microscope slides, histochemical staining, and visual microscopic examination of stained thin sections. This method reliably detects nodal metastases that are present in the examined thin sections, but only a limited number (usually two to three) of thin sections are obtained from the surfaces of thick sections. Because histologic examination is limited to the surfaces of the thick sections, and because those thick sections can be as thick as 3 mm, small metastatic foci residing between the exposed surfaces can escape detection. The entire node volume cannot be practically examined histologically. Furthermore, the postoperative histologic procedure is time consuming (eg, requiring 2 to 3 days). If positive sentinel nodes are identified postoperatively, then the patient must be rescheduled for surgery to perform a formal lymphadenectomy.

Our lymph node studies apply QUS methods to detect small metastases in lymph nodes using high-frequency ultrasound (HFU).29–35 We use HFU QUS estimates to help to differentiate between cancer-containing (ie, metastatic) nodes and cancer-free nodes. Our group previously used spectrum-analysis methods successfully at 10 MHz to show distinct differences between cancerous and cancer-free lymph nodes of breast and colorectal cancer patients36; in those preliminary studies, a single attenuation-independent spectral parameter, spectral intercept, produced an ROC area of 0.97 for identifying metastatic nodes.

Although the QUS methods that we are investigating eventually may allow reliable detection of nodal metastases in touch-prep specimens while the patient remains under anesthesia in the operating room, our immediate objective is to develop high-frequency QUS methods capable of reliably detecting small metastases in freshly excised nodes so that histologic examination can be directed toward suspicious regions of the node and small metastases that reside between thick-section surfaces can be detected rather than being overlooked. Here, we summarize the methods we have developed to acquire and process 3D ultrasound and histologic data, and to estimate four QUS parameters (ie, effective scatterer size, acoustic concentration,15, 16 slope, and intercept12) and to construct color-coded QUS images. The methods and results are illustrated using 46 human lymph nodes from 27 patients with colon cancers who underwent standard surgical resection.

Methods

Surgery and Node Preparation

Lymph nodes were dissected according to standard medical practice from patients with histologically proven primary cancers (breast, colon and gastric cancers) at the Kuakini Medical Center in Honolulu, HI. De-identified patient information used for analysis included patient gender, age in years, primary cancer site, and cancer stage. Pathologists at Kuakini Medical Center also traced the boundary of each cancerous region in every histologic section in every cancer-containing node.

For most cancers, a formal lymph node dissection was performed using the established method for the specific cancer. Sentinel node dissection and intraoperative histologic evaluation was used in selected breast cancer cases. The nodes described in this article were dissected and prepared for pathology according to the current standard of care for surgical treatment of colorectal and gastric cancers only.

The institutional review boards of Kuakini Medical Center and the affiliated University of Hawaii approved the human subject protocols employed in this research.

High-Frequency Ultrasound Data Acquisition

Immediately after surgery, dissected nodes underwent gross histological preparation, which included isolating individual nodes and removing as much overlying fat as possible from each node. Following gross preparation, individual, manually defatted lymph nodes were placed in a water bath containing isotonic saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution) at room temperature and scanned while pinned through the remaining thin margin of fat to a piece of sound-absorbing material.

Ultrasound data were acquired with a focused, single-element transducer (PI30-2-R0.50IN, Olympus NDT, Waltham, MA) with an aperture of 6.1 mm and a focal length of 12.2 mm (ie, an F-number of 2). The transducer had a center frequency of 25.6 MHz and a –6 dB bandwidth that extended from 16.4 to 33.6 MHz.

The transducer was excited by a Panametrics 5900 pulser/receiver unit (Olympus NDT) used with an energy setting of 4 mJ. The RF echo signals were digitized using an 8-bit Acqiris DB-105 A/D board (Acqiris, Monroe, NY) at a sampling frequency of 400 MS/s. The spacing between adjacent scan vectors was 25 mm. A 3D scan of each lymph node was obtained by scanning adjacent planes every 25 mm to uniformly cover the entire lymph node. The total ultrasound scanning time was always less than 5 minutes per node, but the actual duration depended on the size of the node.

Histologic preparation

After ultrasound data collection, scanned nodes were inked to provide visual references for subsequent reassembly of histology into 3D volumes and spatial matching with volumes generated from QUS processing. Red ink was applied to the surface nearest the transducer, blue to the distal surface, and black to the end pointing in the positive x-direction of the apparatus. The complete node was photographed using a digital camera (FujiFilm FinePix S9100; Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with close-up lenses (Hoya Corp, Tokyo, Japan) to estimate the size of the lymph node prior to histologic preparation and to provide a reference for estimating subsequent shrinkage during fixation. We approximated lymph nodes as ellipsoids; sizing a lymph node consisted of measuring its length along the three main ellipse axes.

The sized node then was cut longitudinally, approximately in half and perpendicular to the black-inked region at the junction between the red and blue inks. The two half-nodes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin with the flat cut surface facing downward in the embedding cassette. After fixation, the two half-nodes were sectioned at 65-µm steps if node depth was 5 mm or less or at 115-µm steps if depth was greater than 5 mm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Slides containing the H&E-stained thin sections were evaluated by a pathologist. The pathologist demarcated the border of each detected focus of metastatic cancer. Each slide was placed on a light box and fine-resolution bitmap images of each stained section were acquired using the same digital camera settings that were used for lymph-node sizing. This procedure typically involved at least 30 thin sections per node; it was far more intensive than procedures used in clinical practice, and it assured that no small but clinically significant metastasis would be missed.

The set of bitmap images of the histologic sections was used to reconstruct 3D histologic renderings of the node with an intersection spacing that matched the original separations (ie, 65 or 115 µm) between the thin sections. The 3D histology reconstruction was intended to enable spatial matching of histologically-proven, metastatic cancer foci with their signatures in QUS images.

Three-Dimensional Segmentation

A region-based, semiautomatic, 3D segmentation method was implemented in MATLAB. First, each A-line was down-sampled by a factor of 8 by using the approximation coefficients of the wavelet transform of the A-line envelope computed with Mallat’s pyramidal algorithm.37 The resulting envelopes were log-compressed. Then, the 3D watershed transform was applied.38,39 A pseudo-maximum-likelihood classifier was designed to classify each watershed-deduced region as saline, tissue or fat. The classifier used the mean intensity of each region and assumed that, at a given depth, a saline voxel was less echogenic than a tissue voxel, which was less echogenic than a residual-fat voxel. Human visual inspection was used to verify the correctness of algorithm-based segmentation, and to correct any errors that might have occurred. A previous study showed that even without human correction, the 3D segmentation algorithm produced satisfactory results on a limited, but representative, set of lymph nodes.34

Three-Dimensional QUS methods

Tissue scatterer properties were estimated using high-frequency QUS methods. We then used these estimates to test the hypothesis that scatterer properties are statistically different between cancerous (ie, metastatic) and noncancerous tissue in lymph nodes.

The complete 3D RF data set was separated into overlapping 3D cylindrical ROIs having a diameter of 1 mm and a length (ie, along the axis of the transducer) of 1 mm. The size of the ROI was chosen to allow independent scattering contributions to average. The overlap between adjacent ROIs was adjusted to permit smaller data sets to have sufficient ROIs for statistical stability and to avoid overly long computation times for larger data sets. ROI spacing is equal to voxels size in images that depict QUS values.

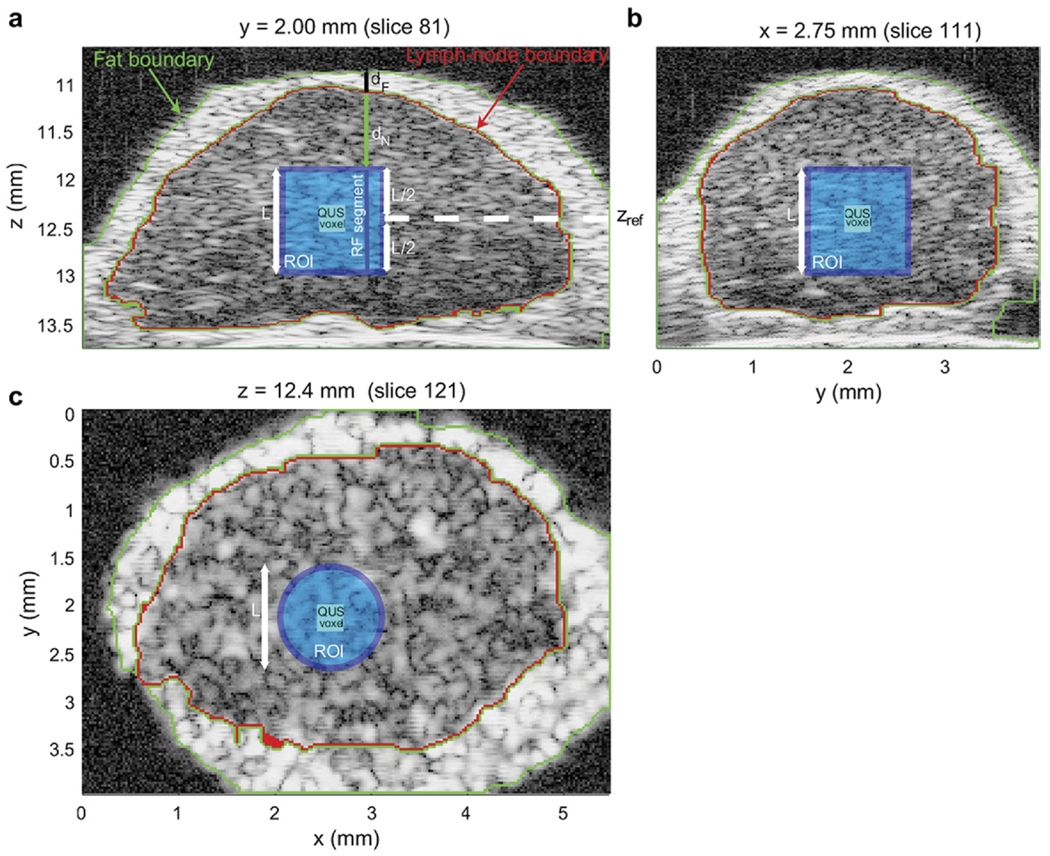

Figure 6 shows three cross-sections of a 3D rendering of a fully segmented lymph node. The green and red highlights show the 3D segmentation results. QUS estimates were computed only when the 3D ROI was entirely composed of lymph node tissue (ie, inside the red highlight). The light blue square in Figs. 6a and 6b and the light blue circle in Figure 6c depict a 3D cylindrical ROI. The dark blue square in Figure 6 depicts a QUS voxel corresponding to the surrounding cylindrical ROI.

Figure 6.

Cross-section images of a 3D volume depicting QUS processing of a colon-cancer lymph node. The light blue regions depict the cylindrical ROI; the dark-blue square depicts the voxel at the center of the ROI.

Water–Oil Calibration

As stated previously, QUS images depict tissue properties in a system-independent manner. To remove system dependence, a common method is to acquire the reflection of a planar reflector over a range of depths ideally using the same instrument settings as those used during lymph node data acquisition. However, tissue is a weak reflector of sound. Therefore, to maintain the same digitizer and pulser settings, calibration ideally would use a planar reflector that also is a weak reflector of sound. In this study, we used Dow Corning 710 oil (Dow Corning Corp, Midland, MI) because it has acoustic properties close to those of water but is denser than water so that ultrasound from a transducer mounted above the interface can propagate with minimal attenuation through an aqueous medium to the weakly reflecting water-oil interface.34,40,41

Attenuation Compensation

A critical part of the signal processing for QUS is accurately compensating for attenuation.42 In this study, attenuation compensation is particularly critical because HFU waves are attenuated more strongly than waves at more commonly encountered, lower frequencies. Attenuation compensation was performed by utilizing an attenuation-compensation function in the frequency domain. Attenuation compensation was conducted individually for every RF segment of each ROI. Figure 6a shows the boundaries of the layer of external, node-enveloping, fatty fibroadipose tissue (in green) and of the lymph node itself (in red). These boundaries were obtained by the segmentation algorithm summarized above. To reach the beginning of the RF segment, sound travelled through two layers of attenuating material with different attenuation values. The first was a layer of highly-attenuating, residual, external fibroadipose tissue (of length dF in Figure 6a) and the second layer was an internal layer of lymph node tissue (of length dN in Figure 6a). Note that values of dF and dN are different for each RF segment of the 3D ROI. (A speed-of-sound value of 1485 m/s was used uniformly for saline, lymph node tissue and fibroadipose tissue.) Compensation was made for the attenuation along each specific RF segment of each specific ROI using a well-known attenuation-compensation function.42

The frequency-dependent attenuation coefficient of fat was measured at 20 MHz to be 0.97 dB/MHz/cm using a spectral-difference method applied to backscattered echoes from the fat tissue of four lymph nodes. The coefficient inside the lymph node was assumed to be 0.5 dB/MHz/cm, which is a typical value for soft tissue.43

Parameter Estimation and QUS-Image Formation

Tissue spectra were computed for each RF segment in each ROI as described above, averaged, and then divided by the calibration spectrum of the water-oil interface located at the center depth of the ROI (ie, zref in Figure 6a). The resulting spectrum was log-compressed to produce the normalized power spectrum.15 Estimates of four QUS parameters were obtained by fitting two different models to the spectra over a ROI-dependent frequency band (ie, the fitting band). The first model was a straight line and led to estimates of spectral intercept and spectral slope. The second model was termed a Gaussian scattering model.13 This model yielded estimates of effective scatterer sizes and acoustic concentration.

The frequency band over which the models were fit was adjusted for each ROI to correct for attenuation-dependent signal reduction at the band edges using an SNR-estimation algorithm. The algorithm was designed to yield wider fitting bandwidths to ROIs with a better-estimated SNR because theory predicts that standard deviations of QUS estimates decrease when the fitting bandwidth increases.12,15,44 If the fitting band was smaller than 10 MHz for a given ROI, then estimates were not computed because the ROI was considered to be too noisy. However, if the fitting band was greater than 20 MHz, then the band was limited to 20 MHz because bandwidths larger than 20 MHz were judged unrealistic based on the properties of the imaging system.

The estimation process was repeated for all ROIs within the segmented lymph node tissue. Three-dimensional QUS images were formed by color-coding and overlaying the parameter values on the conventional B-mode volume. Also, ROIs that were not fully contained in depth between 10.9 mm and 13.3 mm were not processed because they were judged to be too far away from the nominal focal depth of the transducer.

Materials used

The results described in the next section pertain to 112 lymph nodes excised from 77 patients diagnosed with colon, rectal, or gastric cancers. Of these lymph nodes, 92 were entirely negative for metastases and 20 were nearly completely filled with metastases.

Results

The results of our lymph-node studies are summarized here in terms of QUS images and node-tissue classification based on QUS estimates.

QUS Images

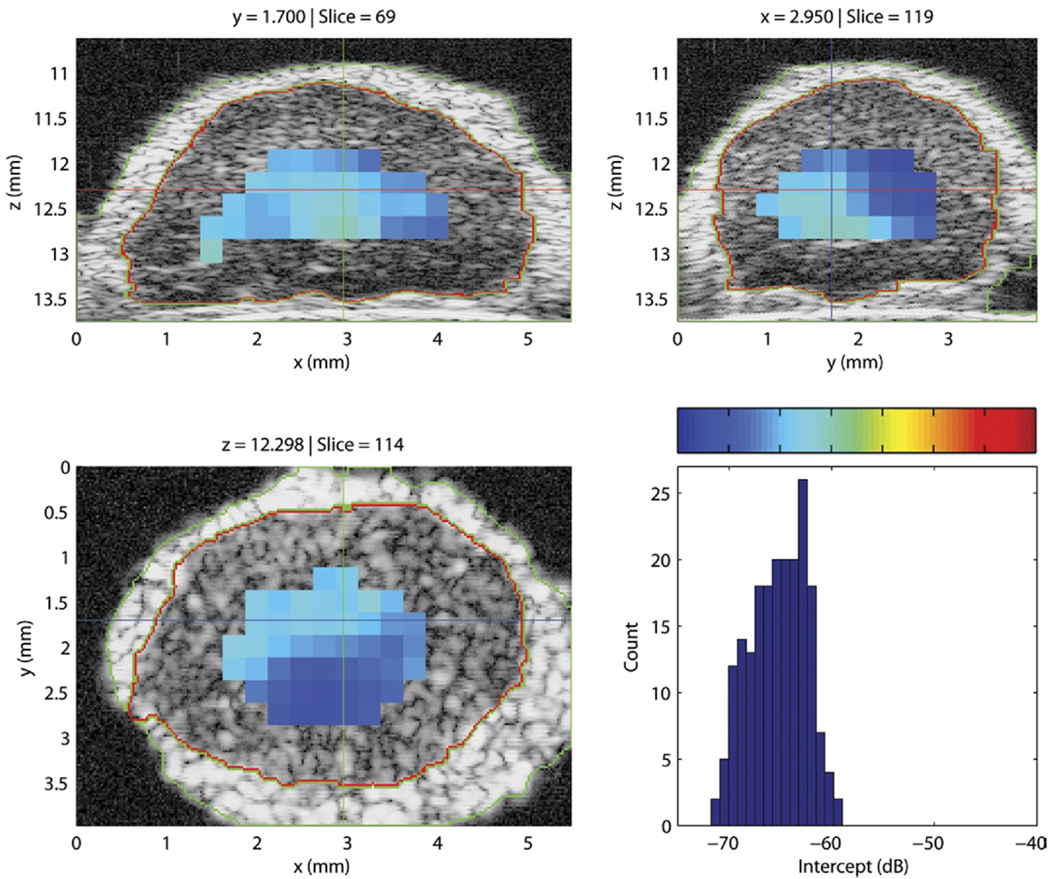

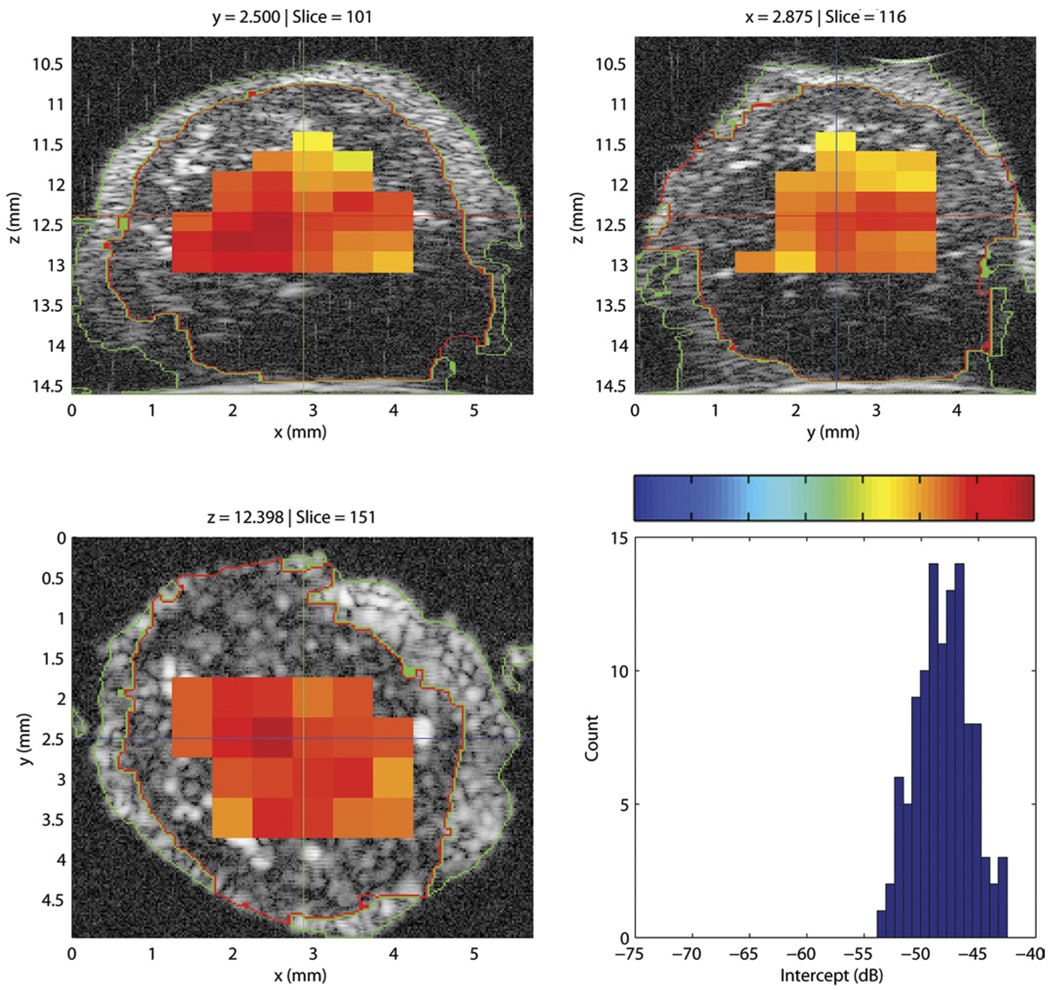

Figure 7 displays the three cross-sections of a QUS-processed lymph node with an overlay of color-coded intercept values. A histogram of the intercept value distribution also is shown in the figure. This illustrative node was entirely nonmetastatic. Intercept values were fairly uniform and were centered around −66 dB. For comparison, Figure 8 displays the intercept cross-sections of an entirely metastatic lymph node from a different patient. For this lymph node, the intercept values were higher, centered around −48 dB. The color-bar scales of Figures 7 and 8 are identical for easier comparison; in both figures, the color-bar values correspond to the intercept-axis values of the histogram.

Figure 7.

Cross-section images of a 3D volume depicting the intercept parameter of a nonmetastatic lymph node. The histogram depicts intercept estimates for the non-metastatic node. The color-bar values correspond to the intercept values of the histogram.

Figure 8.

Cross-section images of a 3D volume depicting the intercept parameter of a metastatic lymph node. The histogram depicts intercept estimates for the metastatic node. The color-bar values correspond to the intercept values of the histogram.

In Figures 7 and 8, the regions that are devoid of estimates in the images either contain ROIs that partially extend outside the node tissue or have a fitting bandwidth that is smaller than 10 MHz, as in the deeper regions of the lymph node shown in Figure 8.

Figures 7 and 8 illustrate how differentiating a metastatic node from a nonmetastatic node is possible. The metastatic node has higher intercept values and its QUS images are red whereas the QUS images of the non-metastatic node are blue. Also, these images indicate that the 3D segmentation is of high quality; what appears to be fat, nodal tissue, and saline solution are clearly demarcated on all cross-sections for both lymph nodes.

QUS images of any of the four parameters would look very similar to those shown in Figs. 7 and 8. The average estimated effective scatterer sizes are 28.6 ± 3.1 and 36.7 ± 2.5 mm for the non-metastatic and metastatic nodes, respectively. Similar contrast also is visible in QUS images of the slope parameter where the mean slope values are 0.30 ± 0.11 for the non-metastatic nodes and 0.01 ± 0.11 dB/MHz for the metastatic nodes. The slope and size estimates are consistent with each other; they indicate that the microscopic tissue structures responsible for scattering in the metastatic nodes are larger than the effective scattering structures in the non-metastatic nodes. Larger scatterers in metastases also are consistent with the observed higher values of the intercept parameter in cancerous nodes.

QUS-Based Lymph-Tissue Classification

For each lymph node, the QUS estimates were averaged for all of the ROIs in which the estimation algorithm returned a value. Then, we evaluated whether correctly classifying lymph nodes was possible based on four QUS estimates: effective scatterer size, acoustic concentration, intercept and slope. Table 1 displays the average and standard deviations of the QUS estimates for the metastatic and non-metastatic nodes. Table 1 indicates that metastatic nodes have significantly larger effective scatterer-size estimates and higher intercept estimates and significantly lower slope and acoustic-concentration estimates. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed statistical differences (p < 0.05) in metastatic and non-metastatic values for all four QUS parameters.

Table 1.

QUS Estimate Values and Standard Deviations for 112 Abdominal Lymph Nodes

| QUS Estimate | Non- metastatic Nodes (N = 92) |

Metastatic Nodes (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| D (µm) | 28.6 ± 3.1 | 36.7 ± 2.5 |

| CQ2 (dB/mm3) | −3.73 ± 2.48 | −7.77 ± 4.31 |

| I (dB) | −63.1 ± 3.8 | −57.7 ± 4.7 |

| S (dB/MHz) | 0.30 ± 0.11 | 0.01 ± 0.11 |

The software package SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used to generate ROCs for each individual QUS estimate and for several combinations of the four QUS estimates using linear discriminant analysis. The results indicate that using effective scatterer size alone, nearly perfect classification performance can be achieved with an AUC of 0.986 ± 0.009. Acoustic-concentration estimates produced an AUC value of 0.829 ± 0.056; therefore, acoustic-concentration estimates alone would classify lymph nodes moderately well. Combining size and acoustic-concentration values does not improve classification performance over D alone. Intercept alone performs as well as CQ2 alone, and slope performs quite well with a performance only slightly inferior to scatterer size alone. Finally, combining intercept and slope values produces an AUC of 0.970 ± 0.015.

Discussion and Conclusions

The methods described here show exciting promise as a novel diagnostic tool for reliable and rapid detection of regions in dissected nodes that are suspicious for metastatic cancer and that warrant targeted evaluation by a pathologist. If successful, the methods we are investigating will be faster and less likely to produce false-negative determinations than current intraoperative touch-prep or traditional postoperative histology. An attribute of the methods is that the complete chain of processing from HFU scanning to QUS-based diagnosis can be made automatic. Therefore, reliable evaluation of the entire lymph node volume could be obtained in a very timely fashion, without human interaction and at lower cost and with less time than is possible using current procedures. The preliminary results are encouraging, and essentially perfect classification results were obtained on a set of 112 lymph nodes dissected from 77 abdominal cancer patients.

DISCUSSION

The advanced ultrasonic tissue typing and imaging methods described here show promise for overcoming many of the limitations other modalities present in imaging and detecting cancer.

The methods for imaging prostate cancer demonstrate performance that is significantly superior to conventional methods of imaging the prostate. Interestingly, some magnetic resonance techniques show similar promise, and we are initiating a study to investigate combining magnetic resonance parameters with spatially co-registered ultrasound spectral parameters, and we expect that this combination of independent modalities will provide exceptional discrimination of cancerous and noncancerous prostate tissue. Success will allow valuable improvements in biopsy guidance, treatment planning and targeting, and treatment-monitoring procedures.

The methods for detecting and imaging cancer foci in lymph nodes are equally encouraging and appear to have the potential for enabling important improvements in guiding biopsy procedures and pathologic assessment with concomitant improvements in cancer staging and treatment planning. A valuable aspect of these methods is that they are amenable to implementation in automated instrumentation in the pathology laboratory; such instrumentation will reliably guide the pathologist to suspicious regions of dissected nodes including small metastases that would otherwise be overlooked using current pathology procedures. We also are planning to extend these methods to evaluations of lymph nodes in situ and thereby develop a means of directing the surgeon to suspicious nodes while allowing the surgeon to leave non-metastatic nodes in place.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research described in this article was supported in part by NIH/NCI grant CA053561 (prostate studies) and CA100183 (lymph-node studies) and by the Riverside Research Institute Biomedical Engineering Fund. Invaluable contributions to the work were provided by Masaki Hata and Emi Saegusa-Beecroft at the Kuakini Medical Center in Honolulu, HI; Alain Coron, and Pascal Laugier at the Parametric Imaging Laboratory of the National Center for Scientific Research and the University of Paris in Paris, France; and Deborah Sparks at the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, WA.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler DD, Carson PL, Rubin JM, Quinn-Reid D. Doppler ultra-sound color flow imaging in the study of breast cancer: Preliminary findings. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16:553–559. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunce SM, Moore AP, Hough AD. M-mode ultrasound: a reliable measure of transversus abdominis thickness? Clin Biomechanics. 2002;17:315–317. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(02)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara K, Pollard R, Borden M. Ultrasound microbubble contrast agents: fundamentals and application to gene and drug delivery. Ann Rev Biomedical Eng. 2007;9:415–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg BB, Liu J-B, Forsberg F. Ultrasound contrast agents: a review. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1994;20:319–333. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klibanov AL. Microbubble contrast agents: targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-assisted drug-delivery applications. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:354–362. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000199292.88189.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremkau FW. Diagnostic ultrasound physical principles and exercises. J Clin Engineering. 1983;8:349. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro RS, Wagreich J, Parsons RB, Stancato-Pasik A, Yeh HC, Lao R. Tissue harmonic imaging sonography: evaluation of image quality compared with conventional sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1203–1206. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson TH, Harris A. Color Doppler ultrasound imaging of the eye and orbit. Surv of Ophthalmol. 1996;40:255–267. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhi H, Ou B, Luo B-M, Feng X, Wen Y-L, Yang H-Y. Comparison of ultrasound elastography, mammography, and sonography in the diagnosis of solid breast lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:807–815. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feleppa EJ, Lizzi FL, Coleman DJ, Yaremko MM. Diagnostic spectrum analysis in ophthalmology: a physical perspective. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1986;12:623–631. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lizzi FL, Ostromogilsky M, Feleppa EJ, Rorke M, Yaremko MM. Relationship of ultrasonic spectral parameters to features of tissue microstructure. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1987;34:319–329. doi: 10.1109/t-uffc.1987.26950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lizzi FL, Greenebaum M, Feleppa EJ, Elbaum M, Coleman DJ. Theoretical framework for spectrum analysis in ultrasonic tissue characterization. J Acous Soc Am. 1983;73:1366–1373. doi: 10.1121/1.389241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Insana MF, Wagner RF, Brown DG, Hall TJ. Describing a small-scale structure in random media using pulse-echo ultrasound. J Acous Soc Am. 1990;87:179–192. doi: 10.1121/1.399283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insana MF, Wood JG, Hall TJ. Identifying acoustic scattering sources in normal renal parenchyma in vivo by varying arterial and ureteral pressures. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1992;18:587–599. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(92)90073-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oelze ML, Zachary JF, O’Brien WD., Jr Characterization of tissue microstructure using ultrasonic backscatter: theory and technique for optimization using a Gaussian form factor. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1202–1211. doi: 10.1121/1.1501278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oelze ML, Zachary JF, O’Brien WD., Jr Parametric imaging of rat mammary tumors in vivo for the purposes of tissue characterization. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1201–1210. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.11.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czarnota GJ, Kolios MC, Abraham M, et al. Ultrasound imaging of apoptosis: high resolution non-invasive monitoring of programmed cell death in vitro, in situ, and in vivo. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:520–527. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolios MC, Czarnota GJ, Ottensmeyer FP, Hunt JW, Sherar MD. Ultrasonic spectral parameter characterization of apoptosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:589–597. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faran J. Sound scattering by solid cylinders and spheres. J Acous Soc Am. 1951;23:405–418. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feleppa EJ, Urban S, Kalisz A, et al. Advances in tissue-type imaging (TTI) for detecting and evaluating prostate cancer. In: Schneider SC, Yuhas MP, editors. Proceedings of the 2002 Ultrasonics Symposium; Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2003. pp. 1373–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feleppa EJ, Ketterling JA, Kalisz A, et al. Application of spectrum analysis and neural-network classification to imaging for targeting and monitoring treatment of prostate cancer. In: Schneider SC, Levy M, McAvoy BR, editors. Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium; Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2002. pp. 1269–1272. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feleppa EJ, Alam SK, Deng CX. Emerging ultrasound technologies for imaging early markers of disease. In: Sampson N, editor. Disease Markers. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2004. pp. 249–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feleppa EJ, Ennis RD, Schiff PB, et al. Spectrum-analysis and neural networks for imaging to detect and treat prostate cancer. Ultrason Imaging. 2001;23:135–146. doi: 10.1177/016173460102300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lizzi FL, Feleppa EJ, Alam SK, Deng CX. Ultrasonic spectrum analysis for tissue evaluation. Special issue on ultrasonic image processing and analysis. Pattern Recog Lett. 2003;24:637–658. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feleppa EJ, Ketterling JA, Porter CR, et al. Ultrasonic tissue-type imaging (TTI) for planning treatment of prostate cancer. In: Walker W, Emelianov S, editors. Medical imaging 2004: ultrasonic imaging and signal processing. Bellingham, WA: Society of Photo-optical Instrumentation Engineers; 2004. pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Gabry E, Halpern E, Strup S, Gomella L. Imaging prostate cancer: current and future applications. Oncology. 2002;15:325–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheipers U, Ermert H, Sommerfeld HJ. Ultrasonic multifeature tissue characterization for prostate diagnostics. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1137–1149. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metz CE. ROC methodology in radiological imaging. Invest Radiol. 1986;21:720–733. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mamou J, Coron A, Hata M, et al. HIgh-frequency quantitative ultrasound imaging of cancerous lymph nodes. Jpn J Appl Phys. 2009;48:07GK8-1–07GK8-8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamou J, Coron A, Hata M, et al. Metastases detection in dissected human lymph nodes using three-dimensional high-frequency ultrasound; Proceedings of the 30th Symposium on UltraSonic Electronics; 2009. pp. 385–386. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mamou J, Coron A, Hata M, et al. Three-dimensional high-frequency characterization of cancerous lymph nodes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:361–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mamou J, Coron A, Hata M, et al. Three-dimensional high-frequency characterization of excised human lymph nodes. In: Yunas MP, editor. Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium; Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2009. pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamou J, Coron A, Hata M, et al. Three-dimensional scatterer-size estimation in dissected human lymph nodes using high-frequency ultrasound; Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Ultrasonic Electronics; Sendai: 2008. pp. 457–458. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coron A, Mamou J, Hata M, et al. Three-dimensional segmentation of high-frequency ultrasound data echo signals from dissected lymph nodes. In: Waters KR, editor. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium; Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2008. pp. 1370–1373. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feleppa EJ, Mamou J, Hata M, et al. Ultrasonic detection of metastases in dissected lymph nodes of cancer patients. In: Lee H, Jones J, editors. Acoustical Imaging. Dordrecht: Springer Publishers; 2011. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feleppa EJ, Machi J, Noritomi T, et al. Differentiation of metastatic from benign lymph nodes by spectrum analysis in vitro. In: Schneider SC, Levy M, McAvoy BR, editors. Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium; Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 1998. pp. 1137–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallat S. A wavelet tour of signal processing — The sparse way. 3rd ed. Burlington, VT: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farnback G, Westin CF. Improving Deriche-style recursive Gaussian filters. J Math Imaging Vis. 2006;26:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soille P. Morphological image analysis — Principles with applications. 2nd ed. Secaucus, NJ: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oelze ML, Miller RJ, Blue JP, Jr, Zachary JF, O’Brien WD., Jr Impedance measurements of ex vivo rat lung at different volumes of inflation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;114:3384–3393. doi: 10.1121/1.1624069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assentoft JE, Gregersenb H, O’Brien WD., Jr Propagation speed of sound assessment in the layers of the guinea-pig esophagus in vitro by means of acoustic microscopy. Ultrasonics. 2001;39:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(01)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oelze ML, O’Brien WD., Jr Frequency-dependent attenuation-compensation functions for ultrasonic signals backscattered from random media. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111:2308–2319. doi: 10.1121/1.1452743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goss SA, Johnston RL, Dunn F. Comprehensive compilation of empirical ultrasonic properties of mammalian tissues. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978;64:423–457. doi: 10.1121/1.382016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaturvedi P, Insana MF. Error bounds on ultrasonic scatterer size estimates. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;100:392–399. doi: 10.1121/1.415958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]