Abstract

Context: Panel management is an innovative approach for population care that is tightly linked with primary care. This approach, which is spreading rapidly across Kaiser Permanente, represents an important shift in population-care structure and emphasis, but its potential and implications have not been previously studied.

Objective: To inform the ongoing spread of panel management by providing an early understanding of its impact on patients, physicians, and staff and to identify barriers and facilitators.

Design: Qualitative studies at four sites, including patient focus groups, physician and staff interviews, and direct observation.

Findings: Panel management allows primary care physicians to use dedicated time to direct proactive care for their patients, uses staff support to conduct outreach, and leverages new panel-based information technology tools. Patients reported appreciating the panel management outreach, although some also reported coordination issues. Two of four study sites seemed to provide a more coordinated patient experience of care; factors common to these sites included longer maturation of their panel management programs and a more circumscribed role for outreach staff. Some physicians reported tension in the approach's implementation: All believed that panel management improved care for their patients but many also expressed feeling that the approach added more tasks to their already busy days. Challenges yet to be fully addressed include providing program oversight to monitor for safe and reliable coordination of care and incorporation of self-management support.

Conclusion: Subsequent spread of panel management should be informed by these lessons and findings from early adopters and should include continued monitoring of the impact of this rapidly developing approach on quality, patient satisfaction, primary care sustainability, and cost.

Introduction

Kaiser Permanente (KP) has long been committed to population care—using a systematic approach to identify and address members' unmet chronic and preventive care needs. Panel management, an innovative approach to population care that is tightly linked with primary care, has been rapidly spreading across KP. Early reports on panel management from innovation sites were promising and garnered a great deal of attention within KP. For example, one innovation site, which had ranked among the lowest-performing regional KP medical centers on Health Employer Data and Information Set measures of diabetes care in 2002, became a top performer in the region in the control of low-density lipoprotein levels within two years of panel management implementation. These and other successful experiences of innovators inspired the spread of panel management to a host of early adopter sites. By early 2007, six of the eight KP Regions and Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (in Washington State) had initiated regionally sponsored activities to support the dissemination of panel management. Implementers pursued three related goals: improving performance on quality measures, strengthening patients' relationships with their primary care physicians (PCPs), and optimizing the use of nonphysician staff in population care. The spread of panel management across KP has been enabled by the availability of flexible information technology tools for population care.

We synthesize here the findings from a qualitative national quality improvement study aimed at understanding staff, physician, and patient experiences of this approach to population care within KP. The purposes of this study were to provide a rapid assessment of early panel management implementation, to provide timely information to subsequent adopters, and to inform later quantitative evaluations of the practice.

Definition of Panel Management

Although panel management is a term that can potentially describe a number of approaches to patient care, we define panel management as a set of tools and processes for population care that are applied systematically at the level of a primary care panel, with PCPs directing proactive care for their empaneled patients. Two features distinguish panel management from KP's previous implementation of population care: 1) processes to identify and address unmet care needs are more tightly linked with primary care practices and 2) less-intense, individualized outreach and follow-up are provided for more patients via telephone contact with panel management assistants (PMAs), who communicate physician recommendations to patients. Some regionalized services continue concurrently (such as individualized care management for high-risk members), but panel management shifts emphasis and resources to supporting PCPs and providing many “light touches” (low-intensity contacts) to patients with unmet care needs.

Panel management is aligned with recommendations for strengthening patients' “primary care home”1 and is also closely related to total panel ownership (TPO), which has been described in this journal.2 We conceptualize panel management as a component of TPO. Whereas TPO is a broad set of practices and an overarching philosophy of physician accountability for access, care, and service for all members in their panels, panel management refers to a narrower and more specific set of tools and processes for outreach purposes.

Larger Context: Shifts in Structure and Emphasis of Population Care

Population care has undergone a broad evolution within KP. KP first implemented structured population care programs in the 1990s, with an emphasis on building needed capabilities within its delivery system.3 Similar health care systems, particularly integrated delivery systems, also took this approach; other organizations have used alternative approaches, especially contracting with external “disease management” companies to provide supplemental services outside the traditional health care system.

KP's initial approach to population care was shaped strongly by recognition that PCPs were already stretched by a large and growing list of expectations.4 Many KP population care services were implemented as regionalized support services, separate from primary care practices and teams, and most were focused on patients with major chronic conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Implementation details have varied among locations and over time, but regionalized services have typically included registries to track patients with chronic disease and identify care gaps relative to evidence-based protocols, automated outreach by mail or phone to inform patients of needed tests or treatment, provision of patient education materials and one-to-many health education classes, and “in-reach” systems to flag unmet care needs whenever registry patients presented for care. Risk-stratification methods, supplemented by physician referrals, identified a small subset of high-risk patients. These patients were offered individualized services from care managers, typically specially trained registered nurses who played a strong, relatively independent role in managing care for high-risk patients, seeing them in person and contacting them by phone to assure that their care conformed to evidence-based protocols and to provide self-management support. Care managers were typically enabled, acting under protocol and within their professional scope of practice, to order routine tests, titrate medication dosages, and perform other routine clinical tasks.

Many KP population care services were implemented as regionalized support services, separate from primary care practices and teams …

This approach yielded very substantial improvement over time on chronic care quality metrics. However, in recent years KP has sought to reinvigorate its slowing improvement on publicly reported performance measures, find ways to realize greater cost savings than were observed in previous chronic conditions management programs,3 and more fully integrate chronic conditions management within primary care. It is within this larger context of changing organizational needs and the desire to optimize and improve the delivery system that panel management emerged. We provide information here on physician, staff, and patient experiences with panel management to inform successful program adoption and spread.

A concerted effort was made to interview both avid supporters of panel management and those more tentative about or critical of this approach.

Methods

Between January and September 2006, we collected qualitative data on four study sites. Data was collected from three distinct sources: 1) direct observation of panel management practices, 2) physician and staff interviews, and 3) patient focus groups. Data from all sources were transcribed and coded using the principles of rapid assessment and qualitative data analysis.5,6

Prior to study data collection, we interviewed 15 leaders and potential adopters from across KP to identify their priorities and needs. These initial interviews also guided the study team in selecting four study sites in three KP regions. Chosen sites had full implementation across an entire facility or area.

Across the four sites, 40 semis-tructured interviews (45–90 minutes long) were conducted with operational leaders, physicians, and staff. Interviewees were selected by a representative from each site who was given a list of sampling criteria from the study project lead. A concerted effort was made to interview both avid supporters of panel management and those more tentative about or critical of this approach. Observation focused on staff communication with patients, physician-staff communication, handoffs between staff and physicians, workflow and program processes, and department- or program-specific meetings.

We conducted one patient focus group at each study site. Patients were selected and recruited by site staff on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: at least one outreach contact by program staff in the past six months; one or more chronic conditions; and, when possible, ethnic and age diversity. Each patient focus group included 8 to 10 patients; many were long-term members whose conditions (primarily diabetes) had been diagnosed at least three years earlier. Topics for discussion included patient expectations and experiences of chronic condition care at KP, preferences for outreach regarding chronic condition care, preferences for the type of staff conducting outreach, and overall experience of panel management communication (phone, letters, physician follow-up, outreach staff follow-up, etc).

Findings

Program Characteristics: Similarities and Differences

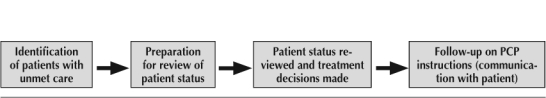

We found wide variation in program implementation characteristics. Basic characteristics—similarities and differences—of the panel management approaches at the four study sites are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. We identified four common components of program implementation: (See Sidebar: Key Components of Panel Management) 1) dedicated physician time for directing clinical decision making related to panel management work; 2) dedicated staff and/or staff time for supporting physicians to complete the work; 3) information technology tools for sorting patients into clinically appropriate groupings and identifying patients requiring outreach; and 4) structured work processes completed on a routine basis. At all four sites, the panel management process included the steps outlined in Figure 1. Although implementation approaches to each of these steps differed across the sites studied, all process steps outlined in Figure 1—except for patient status review and treatment decisions—were primarily carried out by nonphysician staff.

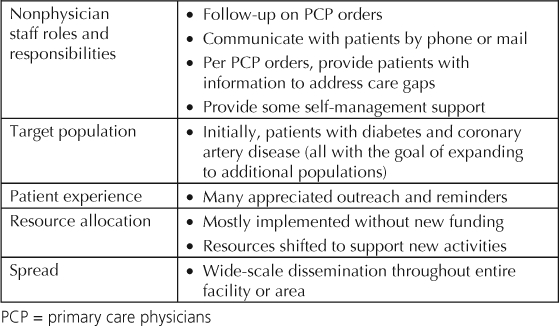

Table 1.

Similarities in implementation across study sites

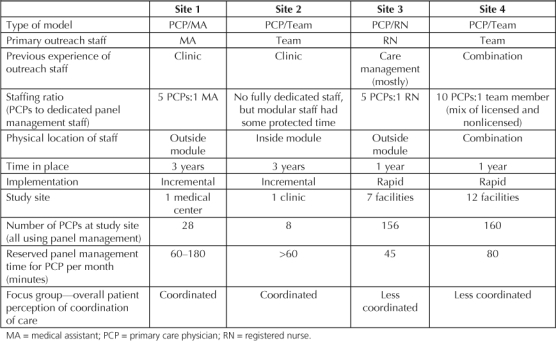

Table 2.

Variation in implementation and site-specific characteristics across studies

Key Components of Panel Management.

Dedicated physician time for directing clinical decision making

Dedicated staff members or staff time to support physicians and conduct outreach

Information-technology tools to identify care gaps

Structured work processes completed on a routine basis

Figure 1.

Panel management process steps.

All four sites had some practices and implementation experiences in common (see Table 1). PCPs directed the clinical decision making, whereas nonphysician staff carried out physician orders. Physicians had designated time to review patient medical record information (eg, two or three 15-minute appointment slots per week blocked off for panel management activities). The implementation of panel management was widespread throughout the facility or area. The shift to panel management involved an operational decision to shift resources from traditional care management or from other programs to support panel management activities.

In three of the four cases, panel management was implemented without new funding. Two sites redirected resources primarily from care management to support panel management implementation. Another site redirected clinic resources to support panel management. The one site that did add resources had been regionally identified as being underfunded for population care management.

Numerous differences between the four sites, illustrated in Table 2, make the inferences about any single factor difficult. The sites varied by size, amount of time the program was fully operational across the facility or area, and/or speed of implementation (incremental versus rapid). Other differences included type of staff used for outreach, previous experience of outreach staff, staffing ratios, whether the program was located within or outside the module, and whether support staff were assigned to panel management only or had other responsibilities as well (eg, rooming patients). Some programs used former care managers for the PMA role; others used former clinic-based staff.

Physician and Staff Experiences

Most physicians reported that they were satisfied with these programs and believed that they were “the right thing to do” for patients. At the same time, many also believed that panel management added more activities to their day; this tension between wanting to do the right thing and desiring to have a sustainable practice came up frequently in interviews with PCPs. Another challenge expressed by physicians concerned the initial implementation process. Some physicians explained that transitioning to a panel management approach required a change in their practice style and thinking. However, over time many (See Sidebar: In Their Own Words: KP Physicians on Panel Management) also came to believe that panel management could better leverage their time during office visits because the program's outreach targeted the nonurgent needs of their patients. Several physicians reported that implementing panel management encouraged them to be more proactive with more of their patients.

In Their Own Words: Kaiser Permanente Physicians on Panel Management.

“Panel management doesn't make my day any easier, but it makes my day better. It improves quality . . . it is better for the patient, but it can add to your day.”

“Panel management has changed my practice by giving me hope that some of my more difficult patients might actually turn around their health status. It has made me more optimistic in approaching these patients; now I work to maximize the number of outreach efforts that occur both from my office and from the panel management staff.”

The nonphysician staff described a wide range of experiences. For medical assistants who were formerly in a clinic, many found that their role in panel management offered opportunities for job growth—most medical assistants interviewed welcomed the new responsibilities. For staff formerly in traditional care management programs, panel management programs represented a major change in their roles, as patient contact shifted from face-to-face interaction to telephonic outreach. These former care managers generally expressed satisfaction with the program, but several expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of face-to-face interactions with patients that they were used to having.

Patient Experiences

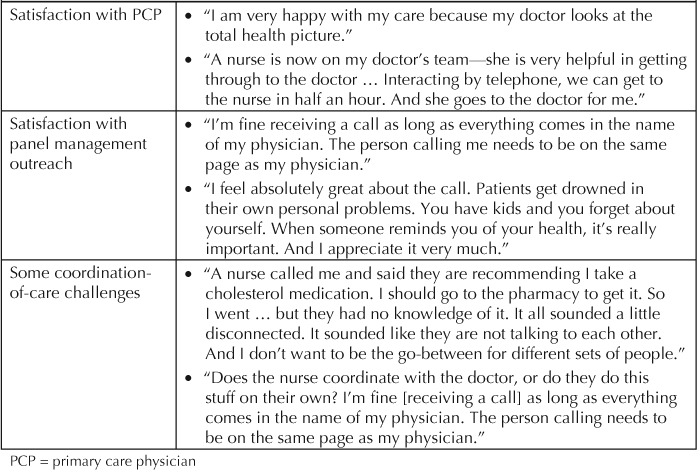

Overall, patients were extremely pleased with their care. They were particularly pleased with their PCPs. They appreciated the reminders, attention, and monitoring related to panel management outreach activities and generally believed that the outreach helped them better manage their condition. Many patients wanted more self-management support in addition to the panel management outreach communications, which tended to center on medications and laboratory results. They wanted more written materials, tailored support especially concerning diet, and classes. In general, patients were open to communications about their care from PMAs. They were generally unsure (but unconcerned) whether outreach staff were nurses, medical assistants, or receptionists. Overall, nonphysician staff were most valued when they gave patients greater access to information flow from their PCP. The resounding message from patients was that although they appreciated the outreach from nonphysician staff, they wanted to have confidence that their physician was directly involved in all aspects of their care, making the clinical decisions that affected their health.

Overall, nonphysician staff were most valued when they gave patients greater access to information flow from their PCP.

Barriers and Facilitators

Coordination of Care

At two of the study sites (see Table 2, sites 1 and 2), patients predominantly perceived their care to be coordinated. They perceived that both the staff member calling them and their PCP were in accord. Patients at these two sites who received outreach calls or mailings were confident that their physician was directing their care and were comfortable with panel management staff communicating on behalf of their physician. At the two other sites, some focus group participants perceived lack of care coordination, with three or more patients at each site reporting experiences of disconnected communication between panel management, primary care, specialty care, and/or pharmacy staff (see Table 3, quotations from patients: “Some coordination-of-care issues”).

Table 3.

Patient experiences—in their own words

Staffing Choices

Panel management staffing choices involved complex trade-offs; factors most salient in staffing choices at the sites we studied were efficiency and cost, clinical effectiveness and quality, physician engagement and sustainability, and resource availability. In terms of staff assignment, panel management can involve many activities within the purview of a medical assistant, whereas some panel management outreach tasks are also appropriate for clerical staff (eg, calling patients to set up appointments). Some implementers believed that the larger scope of practice of nurses, pharmacists, and physician assistants made it more appropriate that they be the ones to accomplish panel management tasks because these staff can provide the necessary self-management support for patients over the phone and greater support to PCPs by making recommendations for treatment. However, observation suggested that use of more-skilled licensed staff may shift the direction of clinical decision-making responsibilities: When PCPs delegated more to staff, they potentially had less control over decision making and a weaker relationship with their patients. The relationship between staffing and role structure is further explored in the Discussion section of this report.

Findings from physician interviews, direct observation, and patient focus groups all suggested that a key factor contributing to effective coordination of care—regardless of scope of practice—is the skill of the outreach staff in communicating with patients and physicians. As one program implementer explained, “A key is getting the right staff for the program—those who can communicate effectively with PCPs and patients, ideally someone with a primary care background, and someone who is comfortable with computers and databases.” Patients expressed less concern about the scope of practice or title of staff contacting them but great concern that those staff members be directly tied to their PCP and be carrying out their physician's orders.

Culture Change

Interviews and observation revealed that as with many other changes to core organizational processes, introduction of panel management presented a culture change that needed to be managed. Some physicians explained that when the program began at their facility, they felt that control of their patients was being taken away from them. Other physicians felt that panel management added extra work with not enough time designated for that work. Some physicians felt pressured to practice in ways that were not comfortable for them, such as being asked to make clinical decisions (eg, the addition of new medications) without having a conversation first with their patient. Some physicians who expressed these concerns explained that over time they came to accept and support the program, whereas others said that they found ways to modify the program to meet their needs and practice style.

Many sites found that a key strategy for supporting implementation was demonstration of performance improvement to staff and physicians. Sites used feedback, ongoing reporting mechanisms for PCPs and staff, and education sessions led by physician champions to support acceptance of panel management as an effective quality improvement tool.

Program Oversight

Panel management implementers explained that close program oversight of outreach staff practices and program processes were essential to their program's success. One implementation team explained that “having standard operating procedures for staff has been critical, especially because our staff work across 12 facilities. We needed to develop these early on and adapt them as necessary. We also needed to educate physicians and patients about how this program works.” Implementers also reported that it is important to closely monitor phone outreach to make sure scripts for staff are clear and that staff are effectively communicating with patients. Some programs have instituted ongoing training or coaching (including peer feedback) for both phone outreach staff and PCPs.

All program implementers believed that process and efficiency measures (number and type of patient contacts for panel management outreach staff and/or PCP review; and changes in patients' health status) should be monitored, evaluated, and reported. Some of the observed programs monitored panel management outreach staff (and PCPs) specifically for volume of patient outreach and follow-up work to gauge the appropriateness of workload. The literature on phone outreach for managing chronic disease notes that if programs are not appropriately designed, telephone care providers or PCPs can become frustrated, burned out, or less aggressive in addressing care gaps.7 One KP program implementer explained, “You need to support the PCPs. Don't make them feel guilty about not getting to the work. Understand their challenges and find ways to support them to get [them] on board.”

Panel management is spreading across KP in the absence of comprehensive quantitative data on its impact.

Discussion

The project reported here was designed as an early, rapid assessment of the potential and transferability of panel management and is subject to several limitations. The number of sites studied (four) is small. The site selection and interviewee selection processes were nonrandom, which could have introduced bias. Also, although there was some indication that two of the four study sites were able to provide better coordination of care from the patient's perspective, the data are not sufficient to attribute this advantage to any specific practice, because multiple confounding factors complicate interpretation of the findings. The two sites that appeared to have stronger coordination of care had been in place much longer than the other two sites, giving the former time to fine-tune the programs and processes. In addition, these two sites implemented panel management in a sequential manner over time, rather than implementing in many modules at once. Although causality cannot be established, this study provides value by identifying potential strengths and limitations that can accompany panel management implementation, so that potential adopters have an opportunity to put in place measures that benefit from the experiences of other sites.

A related limitation of these findings is the lack of quantitative measures to more fully evaluate models. Panel management is spreading across KP in the absence of comprehensive quantitative data on its impact. The changing nature of all components—information technology, people, and process—across KP challenge our ability to develop compelling data on impact. There remains great variation among adopter sites. Issues such as optimal staffing, amount of dedicated physician time, workflow, and communication are still the subjects of experimentation. Currently, programs are not fixed and continue to develop and change. These factors make it challenging to identify superior models or to evaluate models more rigorously at this stage. As a result, the findings summarized here should be regarded as hypothesis-generating. The remaining discussion focuses on hypotheses regarding two specific issues: care coordination and self-management support.

Panel Management and Coordination of Care

A key element in high-quality primary care is care coordination, with all caregivers having detailed knowledge of care the patient is receiving from other sources. Numerous studies have shown that coordination of care is associated with greater levels of population health and patient satisfaction.8–11 In light of patient experiences documented in this study, coordination of care within the panel management process seemed to represent an important area for greater inquiry and attention. For example, in one focus group a patient reported that she was told by panel management staff that medications were ordered, but when she went to the pharmacy there were no medications there. A few examples of this type of experience surfaced in each of the two sites where some patients experienced challenges related to coordination-of-care.

The two relatively more coordinated sites (most patients experiencing their care as coordinated) shared certain features, but as noted, we cannot determine whether these factors directly contribute to the observed differences across sites. Possible contributors to coordination include limited roles for nonphysician staff in clinical decision making; tightly coupled physician–staff relationships with clearly defined and transparent roles for support staff; and program size, maturity, and evolution (see Table 2).

Research on using telephone support to manage chronic disease suggests that using clinic-based staff and tightly linking these types of programs to clinic-based care can contribute to greater program effectiveness. The most effective programs, research suggests, are those that link phone outreach to outpatient care and clinician follow-up.7 However, the evidence of the impact of staffing decisions on program effectiveness is not conclusive.

We hypothesize that one contributor to patient perceptions of coordinated care may be team preparation—more specifically, staff preparedness for the role that they take on in panel management. Patients overwhelmingly expressed tremendous satisfaction with their PCPs and a strong desire to have their PCPs involved in directing their care, but their satisfaction with outreach staff was mixed. It is possible that staff who are accustomed to having a directive role and semiautonomous relationship working with patients may implicitly convey a sense of authority that is inconsistent with the explicit message that the physician is directing the care; this ambiguity of authority may confuse patients. In contrast, nonlicensed staff may give a stronger impression that their role is to support communication between patient and physician, thus preventing any misunderstandings.

We also hypothesize that a second pathway by which use of licensed staff (eg, registered nurses or pharmacists) in the PMA role may affect coordination is the reduction of physician engagement in panel management. At sites where medical assistants conduct outreach, it is possible that physicians are delegating fewer panel management activities and retaining greater personal ownership and responsibility for clinical decisions. By contrast, at sites where PMAs are licensed staff, PMAs—under protocol—have the authority to draft treatment orders for physician review. Physicians with licensed PMA staff may spend less time generating their own orders, thus decreasing their role in directing care and decreasing their role in assuring coordination. Choice of PMA staffing—licensed or unlicensed—is influenced by a tension between the greater efficiency of having orders drafted by nonphysician staff and the potential for decreasing coordination and/or weakening patients' confidence that their physicians are fully overseeing their care.

Other possible factors that might improve the patient experience and contribute to a more coordinated patient experience include “warm handoffs,” with physicians explaining to patients the new roles of panel management staff or activities; strong communication skills for outreach staff, coupled with training programs and education and skills development; and ongoing program oversight. Other factors may also contribute to differences in patient experiences, and these should be factored into further evaluation of panel management activities. Some additional factors might be panel size, collocation of panel management staff and physicians, staffing ratios, and the amount of physician and nonphysician designated time.

Panel Management and Self-Management Support

A second issue, also related to choice of staffing, is the role of self-management support in panel management. Some study sites are coupling proactive outreach with self-management support. Other sites are not doing so, and at these sites, the transition from traditional care management to panel management—with its emphasis on briefer patient contacts—may be decreasing capacity for self-management support. Because self-management support has been identified as an integral aspect of chronic disease care and one that favorably affects health status and health care utilization,12–14 this issue is an important area for additional attention and inquiry.

Conclusion

This new approach to population care has potential for improving quality and enhancing patient relationships with PCPs and teams. Our studies of early adopters point to next steps as this innovation continues to spread: the need for clarification of role definition and scope of practice; development of standardized work flows, training, and scripts that support safe and reliable communication and coordination of care; ongoing attention to management of staffing and expectations so that panel management does not unduly burden PCPs; and maintenance or development of adequate support for self-management.

For a copy of a toolkit on panel management developed in 2007, contact Tabitha Pousson at the Care Management Institute: CMIproducts@kp.org.

Additional research of several types is needed before panel management's impact can be fully understood. Ongoing measurement of patient perspectives regarding their care is required to monitor care quality and patient satisfaction with these new practices. Longer-term studies are needed to identify factors associated with high performance and to evaluate the impact of these programs on quality, cost, and physician and staff satisfaction. Ongoing work at KP will continue to explore and study the impact and promise of this emerging approach.

… nonlicensed staff may give a stronger impression that their role is to support communication between patient and physician, thus preventing any misunderstandings.

Acknowledgments

We extend much gratitude to the leadership and staff at the four study sites for their support of this project and to the KP members who participated in the focus groups. This project has greatly benefited from collaboration with several groups inside KP, including the Care Management Institute's Panel Management Networking Group, the 21st Century Care Innovation Project, the Care Experience Council, and the Northern California Region's Quality and Operations Support Department. Although space constraints prevent thanking everyone who supported the project out of which this article emerged, we thank the following individuals for their support at critical moments in the research, analysis, and/or write-up: Lisa Arellanes, Beth Branthaver, Suzanne Furuya, Lucy MacPhail, Sabine Nicoleau, Helen Pettay, Estrella Shoka, Laura Skabowski, and four anonymous reviewers.

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

References

- The impending collapse of primary care medicine and its implications for the state of the nation's health care: a report from the American College of Physicians January 30, 2006 [monograph on the Internet] Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2006 Jan 31. [cited 2007 May 14]. Available from: www.acponline.org/hpp/statehc06_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Livaudais G, Unitan R, Post J. Total panel ownership and the panel support tool—“it's all about the relationship.”. Perm J. 2006 Summer;10(2):72–9. doi: 10.7812/tpp/06-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fireman B, Bartlett J, Selby J. Can disease management reduce health care costs by improving quality? Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(6):63–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.6.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 31;355(9):861–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J. Rapid assessment process: an introduction. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded source-book. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD. Using telephone support to manage chronic disease [monograph on the Internet] Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2005 Jun. [cited 2007 May 7]. Available from: www.chcf.org/topics/chronic-disease/index. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. Primary care and health: a cross-national comparison. JAMA. 1991 Oct 23–30;266(16):2268–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. Primary care: concept, evaluation, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994 Oct 22;344:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B. Primary care: Balancing health needs, services, and technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001 Nov;39(11):1217–23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002 Oct 16;288(15):1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]