Abstract

With the implementation of the electronic medical record—called HealthConnect—in all exam rooms throughout the Kaiser Permanente health care delivery system, how computers in the exam room affects physician-patient communication is a new concern. Patient satisfaction scores were obtained for all primary and specialty care physicians in a large medical center in Southern California to determine how scores changed as physicians started using HealthConnect in the exam room. Results show no significant changes in patient satisfaction for these physicians. Although concerns were not realized that patient satisfaction might decrease after HealthConnect was introduced, there was also no evidence that introducing an electronic medical record in outpatient clinics increased patient satisfaction.

Early research in Kaiser Permanente's (KP's) Northwest and Colorado Regions examined the impact of exam room computers on member satisfaction with their care experience. Results showed that integration of computers into the delivery of care resulted in improvements in patient satisfaction and patients' opinions of exam room computers were mostly positive. Patient satisfaction improved after physician training and steady-state use was reached.1 Concerns that patient satisfaction would deteriorate with the introduction of computers generally did not materialize. In the literature, a number of studies have been published regarding the effect of a computerized medical record on the physician–patient interaction. Overall, results are generally inconclusive because of methodologic limitations.2–9 For the most part, results were obtained in studies involving computers used by a limited number of clinicians and on the basis of feedback from small samples of patients. In addition, previous studies included primary care physicians. There is little information about patient satisfaction with the interaction with specialty care physicians after computers are introduced in the exam room.

What effect are computers in the exam room having on physician–patient communication and patient satisfaction as HealthConnect is being implemented throughout KP? The magnitude of this intervention is huge. HealthConnect significantly changes the work processes of physicians while the patient is in the exam room. These changes can potentially affect the communication between physician and patient as well as patients' overall satisfaction. When introduced broadly throughout KP, computers in the exam room may have a far-reaching and significant effect on patient perceptions of their outpatient visits. Given the importance of this issue and some methodologic issues with previous studies, we were motivated to study the effect of implementation of a computerized medical record in the exam room with a large number of providers in multiple specialties.

Methodology

This study presents results of patient satisfaction scores for physicians in the Baldwin Park Medical Center—a large KP medical center in Southern California. Baldwin Park patient encounters totaled 1,575,000 in 2005; about 56% of the encounters were with physicians. HealthConnect was implemented in the exam rooms of all clinical departments at this medical center from October 2004 through November 2005. All ambulatory care physicians were involved in and included in this study. The few exceptions were emergentologists and physicians in hospital office visit departments (HOV departments).

When introduced broadly throughout KP, computers in the exam room may have a far-reaching and significant effect on patient perceptions of their outpatient visits.

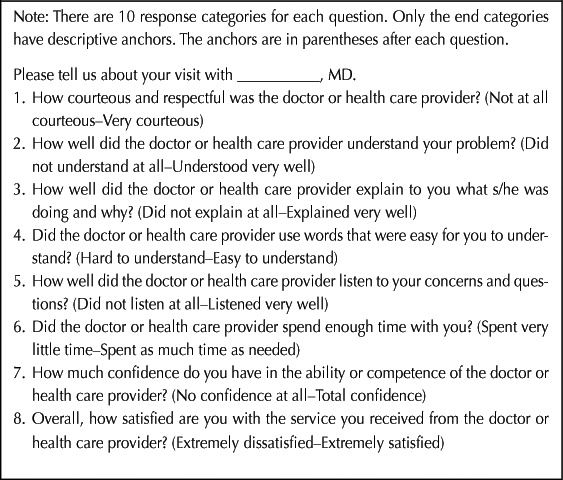

The patient satisfaction survey for the Southern California Permanente Medical Group is the Member Appraisal of Physician/Provider Services (MAPPS). It has been administered since 1994 and is very similar to the Art of Medicine surveys used in other regions. There are eight questions related to the clinician–patient interaction. The response to each question is assigned a score from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most favorable response (Table 1). The combined mean score (CMS) is the calculated arithmetic average of the responses to the eight questions.

Table 1.

Member Appraisal of Physician/Provider Services (MAPPS)

The MAPPS survey is sent to patients who have had recent interactions with physicians. Patients who had an office visit are randomly selected to receive a survey, with the caveat that patients are not surveyed more than once every two months (and no more than once every six months for the same physician). Surveys are mailed out each week to approximately six patients for each physician, with a response rate of about 30%.

For this study, MAPPS data were used from 11,297 patients who were seen by physicians at the Baldwin Park Medical Center from October 2004 through November 2005. Each survey received was placed in one of three categories relative to the point in time when the physician who treated the patient went live with ambulatory HealthConnect. The three categories were “pre 1–3 months” (physician treated the patient 1–3 months before the physician went live with HealthConnect), “post 1–3 months” (physician treated the patient 1 to 3 months after the physician went live with HealthConnect), and “post 4–6 months.” Surveys from the actual month the physician went live with HealthConnect were not included in the study. For the physicians in the study, 4140 surveys were obtained for pre 1–3 months, 3980 surveys were obtained for post 1–3 months, and 3177 surveys were obtained for post 4–6 months.

The MAPPS CMS and the scores for each of the individual MAPPS questions were analyzed for the three time periods.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted separately for primary care and specialty care physicians. There was significant nonhomogeneity of variance for some of the MAPPS questions, indicating that one of the basic assumptions of the F-test (analysis of variance) was not met. As a result, a nonparametric statistic, the Friedman two-way analysis of variance by ranks, was used to analyze the data. In this study, the Friedman analysis evaluated ranks to test the null hypothesis that the samples from the three time periods were drawn from the same population. The statistic used in the Friedman analysis is distributed approximately as χ2.10

Results

The Friedman test required that each physician have data for each of the three time periods. Of the 184 physicians, 168 physicians—115 physicians in primary care (internal medicine, family practice, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics) and 53 physicians in specialty care (such as allergy and ophthalmology)—had a complete set of data.

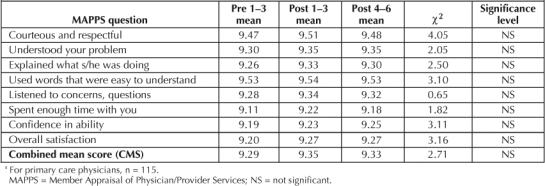

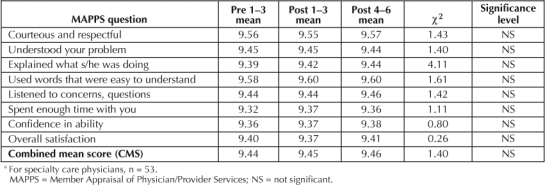

Results of the statistical tests show that no significant differences were found in the ranks of the mean scores among the three time categories for the CMS for physicians in either primary care or specialty care. In addition, there were no significant changes in the responses among the three time categories for any of the individual MAPPS questions for either group of physicians (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of Friedman Tests: Primary Care Physicians a

Discussion

For both the primary care physicians and the specialty care physicians, there were no significant differences in patient ratings of physician–patient communication among the three time periods: 1 to 3 months before implementation of HealthConnect, 1 to 3 months after implementation, and 3 to 6 months after implementation.

On the one hand, decline in patient satisfaction did not materialize, as some had feared. Learning how to use the HealthConnect computer system in the exam room requires considerable changes in how some of the work of physicians is done. New tasks include learning how to enter data, move among the computer screens, make requests for tests or consults, and coordinate with other providers online. However, results show that in the six months after implementation, these considerable changes in work flow did not have a detrimental effect on the ability of physicians to communicate effectively with patients.

Table 3.

Results of Friedman Tests: Specialty Care Physicians a

On the other hand, there was also no indication of improved patient satisfaction when computers were introduced into the exam room. This is contrary to the positive results of the earlier studies in the KP Northwest and Colorado Regions.1 It is likely that methodologic differences between the current study and these other studies explain the different results. The current study used a sample of all physicians in a larger medical center, with each provider serving as his/her own control. This latter feature would eliminate any bias in selecting more physicians with greater communication skills in the study group. The number of surveys returned was substantially larger in the current study as well. It is also possible that the already high scores (CMS of 9.34 out of 10 in the preimplementation period aggregating across all physicians in the study) precluded any significant improvement.

… some key physician behaviors promoted the patient's involvement with the computer during the visit and established the physician's familiarity with the patient.

One limitation to our study was that we did not obtain any information about why changes in patient satisfaction were not observed. However, earlier studies did obtain such information.1 The studies found that some key physician behaviors promoted the patient's involvement with the computer during the visit and established the physician's familiarity with the patient. Physician behaviors that contributed to patient satisfaction included maintaining eye contact, explaining to the patient what the physician was entering in the computer, showing information from the medical record to the patient (such as lab results), and indicating awareness of the purpose of the patient's visit and previous history. In addition, if the patient felt actively involved and perceived that the physician liked the computer, high levels of satisfaction were reached. Finally, it was suggested that if physicians demonstrated how privacy and security can be maintained for patient health information, patient satisfaction scores may not be negatively affected.11

These suggested key physician behaviors were known to the physicians at the Baldwin Park Medical Center, and they were encouraged to implement these behaviors when HealthConnect was introduced in the exam rooms. However, because there was no direct observation of the physician–patient interactions during this period, the extent to which these behaviors were practiced is unknown. Encouraging physicians to establish the key behaviors that are associated with patient satisfaction when computers are in the exam room may result in improved MAPPS scores.

It will be important to emphasize to physicians the steps they can take to demonstrate how computerized technology can contribute to developing trust and confidence in the physician …

In summary, patient satisfaction scores for all ambulatory care physicians in a large KP medical center—both primary care and specialty care physicians—did not significantly increase or decrease in the short period after computers were introduced into exam rooms. Concerns were not substantiated that patients would be less satisfied with the interaction with their physician when computers changed the work-flow processes in the patient visit and, potentially, the dynamics of physician–patient interactions. However, the advantages that the computerized medical record can bring to ambulatory care were also not realized in the one to six months after ambulatory HealthConnect was implemented in the medical center. It will be important to emphasize to physicians the steps they can take to demonstrate how computerized technology can contribute to developing trust and confidence in the physician and improvement in overall patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MAPPS Steering Committee, KP Southern California, for their support. For assistance with data analysis, the authors thank Tonya Premsrirath, Organizational Research, and Raoul Burchette, Research and Evaluation. For assistance with literature review, the authors thank Amisha Gupta, SCPMG Technology Assessment & Guidelines Unit, Clinical Analysis.

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

References

- White J, Slaboch J. AMR and Patient Satisfaction: A Summary of Key Finding from Kaiser Permanente Sponsored Research - CO, HI, NW [monograph on the Intranet] Oakland (CA): Kaiser Permanente Care Experience Council Technology Enabled Care Work Group; 2004 Mar. [cited 2006 Dec 5]. Available from: http://cl.kp.org/pkc/national/operations/cec/technology.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J, Huang J, Fung V, Robertson N, Jimison H, Frankel R. Health information technology and physician-patient interactions: impact of computers on communication during outpatient primary care visits. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2205 Jul–Aug;12(4):474–80. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KB, Serwint JR, Fagan LM, Thompson RE, Wilson MH. Computer-based documentation: effect on parent and physician satisfaction during a pediatric health maintenance encounter. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005 Mar;159(3):250–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison GM, Bernard ME, Rasmussen NH. 21st-century health care: the effect of computer use by physicians on patient satisfaction at a family medicine clinic. Fam Med. 2002 May;34(5):362–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd CS, Penrod LE. Dichotomy between physicians' and patients' attitudes regarding EMR use during outpatient encounters. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000:275–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin CE, Anderson JG, Rosen PN, Felitti VJ, Weng HC. Computers in the consulting room: a case study of clinician and patient perspectives. Health Care Manag Sci. 1998 Sep;1(1):61–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1019021913951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon GL, Dechter M. Are patients pleased with computer use in the examination room? J Fam Pract. 1995 Sep;41(3):241–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein S, Bearden A. Patient perspectives on computer-based medical records. J Fam Pract. 1994 Jun;38(6):606–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legler JD, Oates R. Patients' reactions to physician use of a computerized medical record system during clinical encounters. J Fam Pract. 1993 Sep;37(3):241–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S. Nonparametric statistics for the behavior sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Mann WR, Slaboch J. Computers in the exam room—friend or foe? Perm J. 2004 Fall;8(4):49–51. doi: 10.7812/tpp/14-090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]