Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effects of the murine inhibitory VEGF (rVEGF164b) we generated an adenoviral vector encoding rVEGF164b, and examined its effects on endothelial barrier, growth and structure.

Method

Mouse endothelial cell (MVEC) proliferation was determined by MTT assay. Barrier of MVEC monolayers was measured by trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER). Reorganization of actin and ZO-1 were determined by fluorescent microscopy.

Results

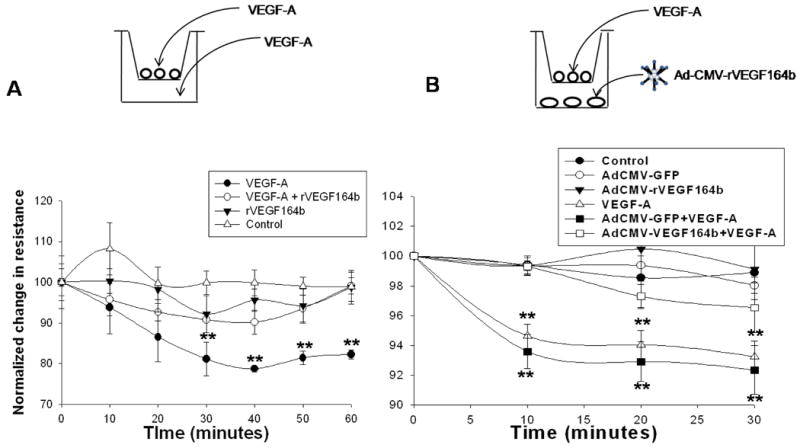

MVECs treated with murine VEGF-A (VEGF-A) (50 ng/mL) increased proliferation (60.7 ±0.1%) within 24 h (p > 0.05) and rVEGF164b inhibited VEGF-A induced proliferation. TEER was significantly decreased by VEGF-A (81.7 ± 6.2% of control). Treatment with rVEGF164b at 50 ng/mL transiently reduced MVEC barrier (p < 0.05) at 30 min post-treatment (87.9 ± 1.7% of control TEER), and returned to control levels by 40 min post-treatment. Treatment with rVEGF164b prevented barrier changes by subsequent exposure to VEGF-A. Treatment of MVECS with VEGF-A reorganized F-actin and ZO1, which was attenuated by rVEGF164b.

Conclusions

VEGF-A may dysregulate endothelial barrier through junctional cytoskeleton processes, which can be attenuated by rVEGF-164b. The VEGF-A stimulated MVEC proliferation, barrier dysregulation and cytoskeletal rearrangement. However, rVEGF164b, blocks these effects therefore rVEGF-164b may be useful for regulation studies of VEGF-A/VEGF-R signaling in many different models.

Introduction

Differential gene splicing of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGF-A) yields homologues of varying length, amino acid composition and pharmacokinetic activity (1). VEGF-A binds three different VEGF receptor complexes: VEGF receptor 1 homodimers (VEGFR1 or Flt-1; 180 kD) or VEGF receptor 2 homodimers (VEGFR2 or Flk-2/KDR-1; 230 kD) or to a heterodimer of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, all of which trigger receptor trans-phosphorylation (2).

VEGF-A production is induced during tissue injury, repair or hypoxia and VEGF-A mRNA translation is tightly controlled to prevent inappropriate VEGF expression that may contribute to pathological inflammation (3,4,5,6). In addition to transcriptional mechanisms, many endogenous inhibitors of VEGF-A mediated angiogenesis exist, including, angiostatin, angiopoietin-1, and thrombospondin (7-9). Also, soluble VEGF receptors 1 and 2 (sVEGFR1 and sVEGFR2) bind VEGF to act as ‘trap’ receptors that block VEGF signals (10,11).

VEGF-A is necessary for maintenance of tissue homeostasis and development as well as induction of endothelial cell proliferation and permeability. However, some VEGF isoforms also function as inhibitors of VEGF-A signaling, and represent important physiological regulators that limit angiogenesis (1,12). In humans, these inhibitory forms, termed VEGFxxxb, can constitute a greater proportion of the total VEGF-A in tissues, far exceeding levels of pro-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms (13,14). In contrast, the VEGF activator to inhibitor ratio can be reversed in some cancers, triggering tumor angiogenesis (12). The stoichiometric ratio of activating and suppressing VEGF isoforms is not yet a well recognized concept, but may be as important to the control of angiogenesis as transcriptional and translational regulation is to control of VEGF-A.

Like the human VEGF165b, the mouse homolog (known as VEGF164b) results from alternate splicing of the VEGF-A gene in exon 8 downstream of the pro-angiogenic splice site, resulting in a shift in frame and a change in the last 7 amino acids from RCDKPRR to PLTGKTD. This different COOH terminal sequence competes with pro-angiogenic VEGFs for VEGF receptors 1 and 2 and inhibits signaling (1). Currently, the specific ratios of activating (VEGF164) and inhibitory (VEGF164b) isoforms represented by VEGF developmental and tissue expression patterns in the mouse is undefined.

In this study, we examine the inhibitory effects of a recombinant VEGF164b (rVEGF164b) on VEGF-A mediated endothelial proliferation, barrier function and cytoskeleton reorganization. Our findings show rmVEGF164b is an important regulator of microvascular structure and function and a potential target in cancer and inflammation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Adenovirus construction

The 570 base pair coding sequence of mouse VEGF164b cDNA was synthesized by GeneScript Corp. (Piscataway, NJ) and subcloned into the pUC57 shuttle vector. This coding sequence omitted a single arginine residue at the COOH terminal of the murine VEGF164b to alter the biological properties of the natural VEGF164b, resulting in a novel recombinant inhibitory VEGF isoform, rVEGF164b. The rVEGF164b cDNA was subcloned into the adenovirus shuttle vector pAdenoVator CMV5 (MP Biomedicals; Solon, OH). The shuttle vector containing the rVEGF164b coding sequence was linearized with PacI, and co-transformed with pAdenoVator ΔE1/E3 (containing the adenovirus backbone sequence) into the E. coli strain BJ5183 for homologous recombination. After isolation of recombinants from positive clones, an adenovirus vector Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b, was rescued by transfection of PacI linearized plasmid DNA into the HEK293 packaging cell line.

Cell culture

Mouse Venous Endothelial Cells (MVECs) isolated from the vena cava of an immortomouse were maintained in culture using D-valine medium (Promocell; Heidelberg, Germany) as described previously (15). Prior to experimental procedures, the MVECs were transferred into DMEM containing 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) with penicillin/streptomycin for 72 h at 38.5° C and subsequently serum starved for an additional 24 h in DMEM containing 1% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin at 38.5° C. Cell culture at 38.5 C eliminates expression of a temperature sensitive Large T antigen, which decreased growth and differentiation 16. All experiments involving MVECs were carried out in the basal starvation medium at 38.5° C unless otherwise stated. Young Adult Mouse Colonic Epithelial Cells (YAMCs), a kind gift of Jenifer I. Fenton, Ph.D. (Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, College of Nursing, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) were maintained in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FCS, insulin/transferrin, non-essential amino-acids, and L-glutamine at 33° C. YAMCs were cultured at 38.5° C for 72 h followed by serum starvation as described above for the MVECs prior to experimental procedures. The A549 human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and was cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS with penicillin/streptomycin at 37° C.

Analysis of sequence properties

Full-length cDNA sequence of the rVEGF164b was translated into the corresponding amino acid sequence and was used to determine the polarity and hydrophobicity of the COOH terminus. All analysis was performed with the GIST software package (http://bioinformatics.ubc.ca/gist).

Kinetics of rVEGF164b protein production

A549 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 infectious units (i.f.u.) per cell with adenovirus Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b in DMEM medium containing 2% FCS for 2 h and then returned to normal culture conditions for 72 h. Cells and media were harvested at 72 h by scraping, and the collected medium/cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min. Total concentration of VEGF164b was determined by ELISA (Mouse VEGF DuoSet, R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN). The cleared medium was filtered at 0.22 μm and frozen at -80° C in 200 μL aliquots.

Western blotting of VEGF164b

Cells (A549 or YAMC) were infected with either a 100:1 MOI of Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b, or an equivalent MOI of a control adenovirus (Ad5-CMV-GFP) expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP), and cultured for 48 h. Media and cell pellets from YAMCs were harvested and separated on non-reducing sample PAGE gels (7.5%) run at constant voltage (100 V). Culture media and cell protein from A549 were harvested and run under reducing conditions on 10% SDS PAGE gels. Gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Idea Scientific, Minneapolis, MN) and blocked in PBS containing 5% non-fat milk and 0.1% fish gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Primary incubations were performed for 2 h in PBS containing 0.1% non-fat milk and 0.1% fish gelatin using a 1:500 dilution of rat anti-mouse VEGF-A raised against a peptide containing the murine sequence Ala27 - Arg190 (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN). Secondary incubations were performed for 1 h using a rabbit anti-rat IgG (1:1000 dilution) linked to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich). Finally, the membranes were developed using the ECL substrate (Amersham Biosciences; Pittsburgh, PA), and exposed to X-ray film.

VEGF164b ELISA

ELISA assays were performed as specified using a VEGF164 specific kit (Mouse VEGF DuoSet, R&D Systems). Serial dilutions of sample media were prepared at 1:1 to 1:10,000 from either A549 or YAMC culture flasks infected as described for protein production or from A549 cells infected with a 1:10 titer to determine protein production kinetics. Media for daily (24 h) protein production kinetics were harvested by full removal and replacement of media each day from cells infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b. In a separate experiment media from infected cells were harvested from separate groups at 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h to determine total cumulative protein levels. Measurements were taken from dilutions that fell within the linear range of the standard (1,000 – 62.5 pg). The plates were read in a Spectromax 96 well plate reader (MDS, Inc; Sunnyvale, CA).

Proliferation and metabolic assays

The effect of rVEGF164b of VEGF-A on endothelial proliferation was assessed by both MTT reduction assay and direct cell counting. For the MTT proliferation assay serum starved MVECs that were plated at 10% confluence (∼ 3,700 cells/well) in 2% porcine gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) coated 96 well dishes in DMEM containing 1% FCS and allowed to adhere for 3 h. Medium was removed from the wells and experimental media containing 50 ng/mL VEGF164, 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b, a combination of both 50 ng/mL each of VEGF-A and rVEGF164b, an equivalent volume of medium from GFP infected A549 cells, or 1% FCS alone (n = 32). The cells were grown at 38.5° C to maintain growth factor dependence for 24 h at which time the medium was removed and MTT (0.5mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) in phenol red free RPMI 1640 was added to the wells. The plates were incubated at 37° C for 2 h, and afterwards the medium was removed and the reduced MTT was dissolved by the addition of acidified isopropanol to each well. To determine if increased MTT reduction reflected increased proliferation or mitochondrial activity, MVECs were plated and allowed to reach 100% confluence. Culture media were removed and treatments added as described. 24 h later, MTT in phenol red free RPMI was added and incubated for 2 h and reduced MTT extracted with acid/isopropanol. The absorbance was read at 570 nm (subtracting background at 650 nm); all data were normalized to controls. Cell counts were performed in 96 well using serum starved MVECs plated at 100 cells per well for 24h in experimental media (as described). Cells were fixed in 1% formalin and stained with 0.05% crystal violet (2 h) and counted at 4× magnification. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test using InStat software (GraphPad; La Jolla, CA).

Trans Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

The 24 well PETP transwell inserts (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) were coated with 2% porcine gelatin and seeded with MVECs in DMEM containing 10% FCS and allowed to grow to confluence. After confluence was reached the medium was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 1% FCS for 24 h prior to the experiment. Experimental media containing 50 ng/mL VEGF-A, 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b, a combination of both VEGF-A and rVEGF164b (each at 50 ng/mL), or 1% FCS alone was placed in both upper and lower chambers to ensure consistent concentration of VEGFs were maintained. Resistance readings were taken at 10 min intervals using an epithelial voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments; Sarasota, FL). Data were converted to % resistance at time = 0. Repeated measures were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test to determine significant (p < 0.05) departure from basal resistance.

TEER of MVECs co-cultured with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b infected epithelial cells

YAMC cells were plated in 24 well dishes and grown to confluence, and serum starved (as described). The YAMCs were infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b (at 1:1, 10:1, or 100:1 MOI), with a GFP expressing adenovirus (Ad5-CMV-GFP) at 100:1 MOI, or were mock infected (using PBS) in DMEM containing 2% FCS for 2 h, at which time the medium containing virus or mock was removed and replaced with fresh medium. MVEC were plated as described for TEER and cultured separately from YAMCs until the beginning of the experiment. The concentration of VEGF-A in inserts was adjusted to 50 ng/mL (upper chamber alone), and TEER readings were taken at 10 min intervals (for up to 60 min). After 60 min, the medium in the upper chamber was exchanged with DMEM containing 1% FCS. The protocol was repeated at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after infecting YAMC target cells. Repeated measures were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test to determine significant difference from resistance at time = 0.

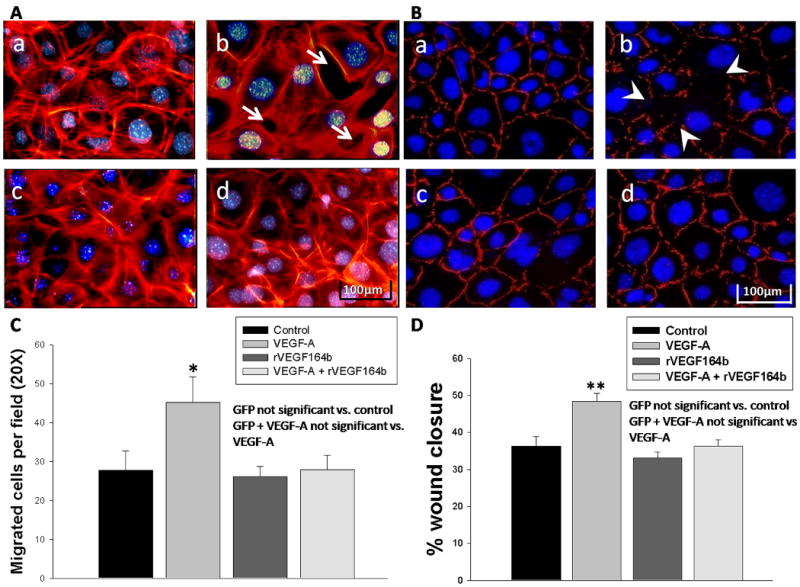

F-Actin reorganization

Mouse Venous endothelial cells were grown on 8 chamber culture slides (BD BioScience; San Jose, CA) coated with 2% porcine gelatin until confluence in DMEM medium containing 10% FCS followed by serum starvation. At confluence the culture medium was change to DMEM containing 1% FCS for 24 h prior to application of experimental media. After 24 h the medium in the chambers were replaced with DMEM containing 1% FCS and the following: 50 ng/mL VEGF-A alone, 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b alone, or 50 ng/mL each of VEGF-A and rVEGF164b. At 45 min, cells were fixed in 1% PBS formalin for 30 min, followed by 3 washes with Ca2+ and Mg2+-free PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min followed by 3 washes in PBS. The cells were stained with rhodamine phalloidin for 30 min followed by 3 washes in PBS. The slides were mounted with medium containing DAPI nuclear stain (Vector Labs; Burlingame, CA). The slides were imaged at 40× magnification on an Olympus BX50 microscope.

ZO-1 immunostaining

MVECs were grown to confluence on 1.5cm glass cover slips coated with 2% gelatin. Following the starvation procedure (above), the cells were treated with control medium (DMEM containing 1% FCS), 50 ng/mL VEGF164, 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b, or a combination of 50 ng/mL each of VEGF-A and rVEGF164b. Cells were pretreated for 2 h with rVEGF164b prior to the addition of VEGF-A, and cultured an additional 2 h in the presence of VEGF-A. Cells were fixed in 1% phosphate buffered formalin for 30 min, extracted with 0.1% Triton X-100, and followed by a 2 h blocking period in 10% normal goat serum. Cover slips were incubated in a 1:200 dilution of rabbit anti-mouse ZO-1 (Zymed Laboratories; San Francisco, CA) for 2 h followed by incubation with 1:200 dilution of Cy3 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG for 2 h (Jackson Labs; West Grove, PA). Slides were mounted using fluorescence preserving medium containing DAPI nuclear stain (Vector Labs). Images were taken at 40× magnification on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

Transwell migration assay

MVEC seeded at a density of 3×104 cells in 24 well inserts in either 1 ml of control or experimental media (VEGF-A at 50 ng/mL, rVEGF164b at 50 ng/mL, GFP conditioned medium, a combination of VEGF-A and rVEGF164b, or a combination of VEGF-A and GFP conditioned medium) for 18 h at 37°C. The top chamber was swabbed free of cells and washed with PBS. The bottom of the insert was fixed and stained in 1% formalin with 0.05% crystal violet (30 min) washed and mounted for counting. 3 20× fields were counted per insert (>2 fields away from the edge of membranes). The total migrated cells per field was determined and statistical significance determined by ANOVA with Dunnett's post test.

Scratch wound assay

MVECs were allowed to grow to confluence in 96 well dishes and starved as described. Monolayers were wounded with the tip of a 1000 μL pipette tip after which starvation medium was removed from the wells and experimental media was added to the wells. Cells were allowed to migrate for 18 h at which time cells were fixed and stained in 1% formalin with 0.05% crystal violet for 30 min. Wound tracks were imaged at 4× magnification and width of wound tracks were measured (in μm) and divided by 1600μm (width of original wound track) to determine the % wound closure. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post test.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) in all quantified values. InStat v3 was used to perform data analysis by one-way ANOVA (proliferation studies) or repeated measures ANOVA (barrier studies) with post-hoc comparisons using Dunnett's test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant (*); p values less than 0.01 were considered highly significant (**).

Results

Analysis of sequence properties

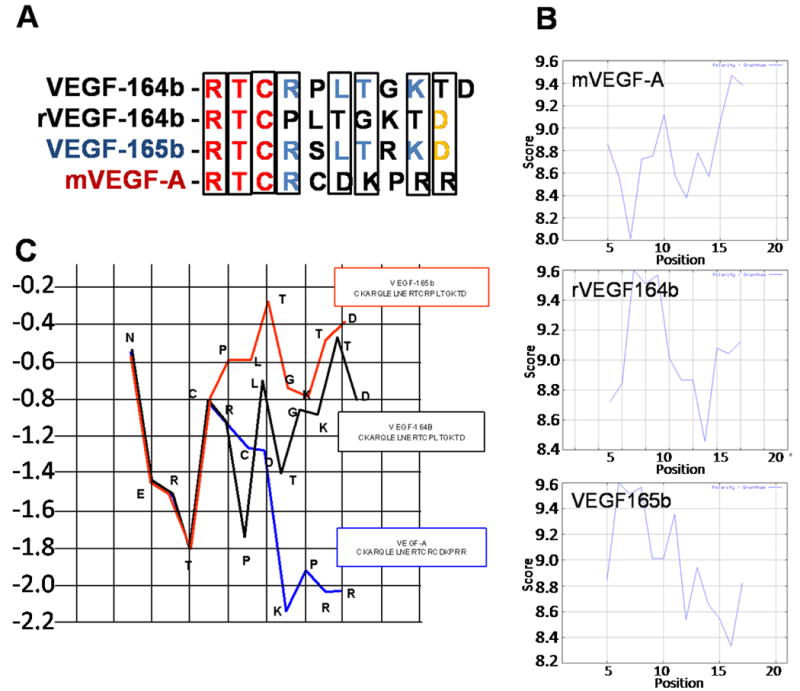

We designed a novel adenoviral vector (Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b) that expresses an inhibitory VEGF isoform termed rVEGF164b (recombinant). This isoform was modified to have a broad tropism and high level of potency in mouse models by deleting a single amino acid residue. As shown in Figure 1A, the sequence of the COOH terminal end of the recombinant VEGF164b construct expressed in the adenovirus vector represents a change in the mouse sequence of VEGF164b as predicted, resulting in a novel isoform of inhibitory VEGF (rVEGF164b). The deletion of a single arginine residue at the COOH terminal end of the predicted mouse VEGF164b alters the polarity (Figure 1B) and hydrophobicity (Figure 1C) profile of the inhibitory VEGF bringing it closer to the physical properties of human VEGF165b. The polarity of the rVEGF164b closely matches the predicted human VEGF165b (Figure 1B), with both having a predominantly neutral charge spanning the 7 terminal amino acids, while VEGF-A has a net negative charge (Figure 1B). Likewise, the inhibitory VEGFs (r164b and 165b) are much more hydrophobic when compared with the pro-angiogenic isoform of VEGF-A (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Sequence alignment of the predicted COOH terminal of VEGF164b with rVEGF164b, VEGF165b, and VEGF165. (B) Grantham polarity plots of the COOH terminal end of VEGF-A, VEGF165b, and rVEGF164b. (C) Hydrophobicity plots of the COOH terminal of VEGF-A, VEGF165b, and rVEGF164b.

We predicted this modification would maintain competitive receptor affinity of the VEGF and allow cross species interactions of the molecule for mouse and human VEGF receptors, thereby increasing the possible uses of the adenoviral construct. This novel inhibitory VEGF, rVEGF164b, was expected to have similar potency towards endothelial cells of both human and mouse origin. However, studies using rVEGF164b demonstrated minimal blocking effects on human endothelial cells (data not shown). This result was unexpected given the overlap in the effect of VEGF165, VEGF164, and VEGF165b between human and mouse species (17-20). Nonetheless, the species specificity of rVEGF164b activity is ultimately useful as it provides investigators a novel tool to isolate the role the host vasculature plays in many xenograft models ranging from cancer to psoriasis.

Biochemical characterization of adenoviral protein product

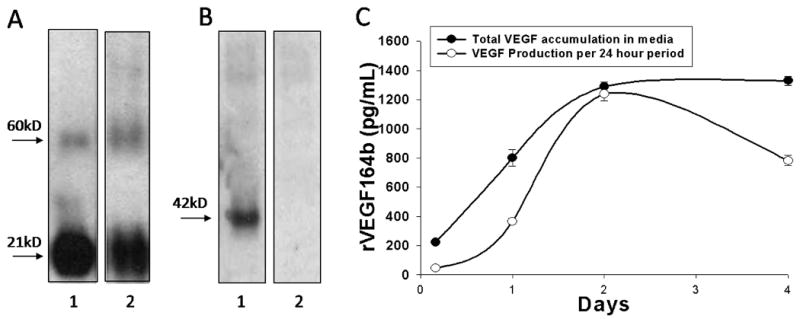

To characterize rVEGF164b expression in cells infected with the adenoviral vector denaturing, non-denaturing Western blotting and ELISA were performed. The anti-mouse VEGF-A antibody was found to detect denatured and non-denatured forms of both VEGF-A and rVEGF164b, since this antibody recognizes a common peptide sequence between Ala27 - Arg190 of the VEGF sequence. Figure 2A shows immunoblotting results for 50ng of control VEGF-A (R&D Systems) (lane 1). VEGF-A appears as a 21kd monomer (reducing conditions). Similarly, lane 2 shows 50ng of rVEGF164b is also detected as a 21kD monomer. Additional bands detected at 60 kD correspond to multimers of VEGF-A and rVEFG164b. As shown in Figure 2B, the anti-mouse VEGF-A antibody detected rVEGF164b as a single dimer with a MW of approximately 42 kD in lane 1 under non-denaturing conditions while no comparable band was detected in Ad-GFP infected cells.

Figure 2.

(A) Denaturing Western blot of rVEGF164b from A549 cells 48 h post-infection showing 50ng of native murine VEGF-A protein (lane 1) and 50ng rVEGF164b in conditioned medium (lane 2). Both bands appear at 21kDa as expected, the higher molecular weight band is non-specific interaction of the antibody with BSA. (B) Non-denaturing Western blot of Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b infected YAMCs (lane 1) and uninfected cells (lane 2). Bands appear at 42kDa which corresponds to a VEGF dimer pair (biologically active form) of the protein. (C) Production of rVEGF164b in A549 measured by ELISA. Total VEGF accumulation in media represents total accumulated VEGF in media at the corresponding time point and VEGF production per 24 hour period shows total VEGF production during the indicated 24 hour time point. Bars are means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent measurements.

A549 cells produced rVEGF164b with up to 17 μg/mL of rVEGF164b present in conditioned medium at 72 h. As shown in Figure 2C, peak adenovirus induced rVEGF164b protein production occurs at 48 h post-infection and decreased afterwards to approximately 1 × 10-6 μg/cell/24 h. Despite the decrease in peak protein production Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b infected cells after 48 h, concentrations remained stable in medium at 96 h after infection with no discernible increase or decrease. These results show that cells infected with the Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b vector produce rVEGF164b. Production of rVEGF164b from conditioned medium of A549 cells infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b was used for the following in vitro growth and barrier studies to examine biological activity.

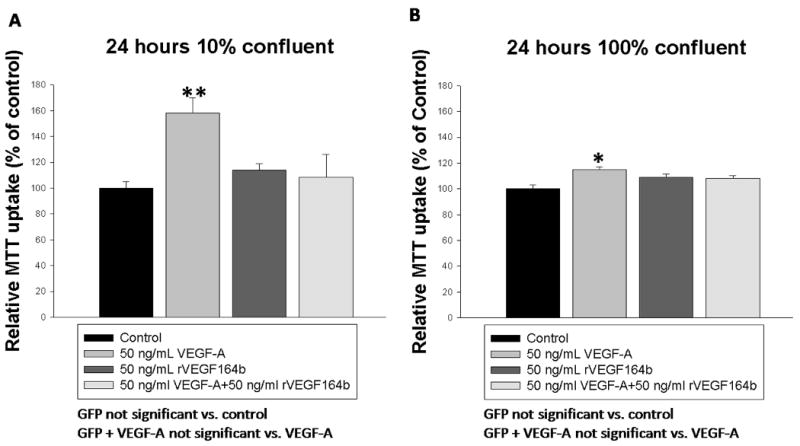

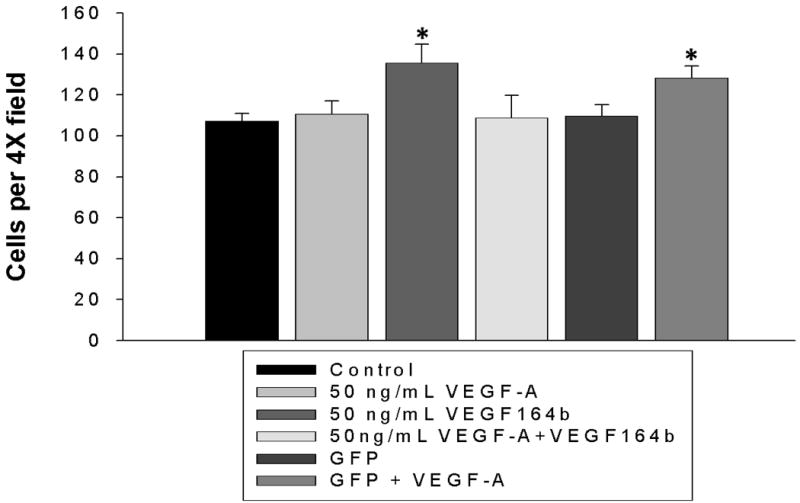

Cell proliferation and metabolic increase in response to VEGF-A is blocked by rVEGF164b

MTT uptake and cleavage was used to determine the effect of VEGF-A and rVEGF164b on MVEC proliferation. As shown in Figure 3, MVECs treated with 50 ng/mL VEGF-A showed a significant (58% ± 11.6%) increase in cell proliferation at 24h compared with control untreated cells (p < 0.05). The increase in proliferation due to VEGF-A represents a doubling time of approximately 30 h under low (1%) serum conditions. This result is in contrast to a 3-fold increase in MVEC proliferation under normal (10%) serum conditions during the same time period (data not shown). Interestingly, the increase in proliferation caused by VEGF-A was blocked by addition of an equal concentration of rVEGF164b using conditioned medium. Co-treatment with 50 ng/mL VEGF-A and conditioned medium containing 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b resulted in inhibition of cell proliferation to levels not significantly different from contol (figure 3 A). Importantly, the addition of conditioned medium containing rVEGF164b alone to MVECs caused no change in proliferation, nor did the addition of control medium from Ad-GFP infected cells. Additionally the experiment was repeated using human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECS) under same conditions and treatments but rVEGF164b was unable to block proliferation induced by VEGF-A (supplementary figure 1). VEGF-A stimulation of endothelial proliferation might also increase cell respiration 21. We therefore compared effectd of VEGF-A and VEGF-164b on MTT reduction in confluent (non-proliferating) and subconfluent (proliferating) MVEC cultures. MTT reduction increased 58 ± 11.6% in proliferating cells consistent with increased numbers of cells. In confluent endothelial monolayers, MTT reduction was also significantly, increased but to only 14 ± 2.2% above control levels. Further, rVEGF164b inhibited VEGF-A induced respiration in confluent cells (not sig. different from control) suggesting that rVEGF164b blocked VEGF-A induced respiration independent of effects on EC proliferation (figure 3 B). Cell proliferation analysis using MTT was reinforced by direct cell-counting. In control MVEC, proliferation increased significantly with VEGF-A (35.50 ± 9.24%) at 24h vs. 7.25 ± 3.79% in controls. rVEGF164b blocked VEGF-A induced proliferation to only 9.75 ± 5.43%. (GFP alone, or in combination with VEGF-A had no effect on cell proliferation (figure 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Inhibition of VEGF-A induced proliferation by rVEGF164b in MVECs seeded at 10% confluence at 24 hours as measured by MTT conversion (n = 32). (B) Measurement of VEGF-A induced mitochondrial activity by MTT conversion in fully confluent MVECs and inhibition by rVEGF164b (n=16). Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Cells seeded at low density (100 cells/0.33cm2) were treated with media containing VEGF-A, rVEGF164b, a combination of the two or control media. Cell number was counted at low power (4×). rVEGF164b significantly inhibited VEGF-A induced proliferation. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05.

Trans Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

We used TEER to examine the effect of rVEGF164b on barrier function of endothelial monolayers. As shown in Figure 5A, control untreated MVEC monolayers resistance remained stable during the 60 min time course at a basal level of 434 ± 11 Ω/cm2 at the start of the experiment although media exchange did cause a small (not sig.) elevation in resistance. The addition of 50 ng/mL VEGF-A to MVEC monolayers significantly reduced the resistance to 81.7 ± 6.2% of control levels, showing a decrease in resistance to 354 ± 29 Ω/cm2 after 10 min. This decreased level of TEER persisted for at least 120 min (data not shown). In contrast, addition of conditioned medium containing 50 ng/mL rVEGF164b alone caused a transient 87.9 ± 1.7% decrease in resistance at 30 min to 382 ± 7 Ω/cm2. However, this decrease returned to initial resistance by 40 min after treatment. Importantly, co-treatment of MVECs with rVEGF164b and VEGF-A prevented the VEGF-A mediated change in barrier function, resulting in a resistance profile similar to rVEGF164b treatment alone. We also examined the duration of rVEGF164b inhibition on VEGF-A mediated barrier permeability. This was tested by an initial treatment of MVEC monolayers with conditioned medium containing rVEGF164b followed by addition of VEGF-A after resistance returned to control levels at 40 min (supplemental figure 4A). This subsequent treatment with VEGF-A after initial treatment with rVEGF164b resulted in no decrease in resistance. We also allowed a longer recovery period of 90 minutes in a separate experiment and found that rVEGF164b blocked VEGF-A mediated decrease in TEER in this instance as well (supplemental figure 4B). These results demonstrate the effect of rVEGF164b is can block VEGF-A induced changes to barrier function and this effect is durable, lasting after the initial transient changes to prevent VEGF-A induced reduction in barrier function in the MVEC monolayers.

Figure 5.

(A) Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) of MVECs testing for inhibition of VEGF-A mediated decrease in barrier function. Resistance was significantly decreased by VEGF-A for 60 min post treatment and did not return to normal for at least 120 min. Resistance returned to normal in rVEGF164b and VEGF-A + rVEGF164b treated monolayers at 60 min post-treatment. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Results were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test for deviation from resistance at time = 0. *p < 0.05, n = 3. (B) TEER readings of MVECs cultured above YAMCs infected with 100:1 titer of Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b following a 50 ng/mL spike of VEGF-A at 48 h. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Protection was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6.

TEER of MVECs co-cultured with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b infected epithelial cells

To determine if cells infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b could secrete a biologically active rVEGF164b and act in a paracrine fashion to inhibit VEGF-A induced pro-angiogenic activity. We used a transwell assay in which YAMCs were cultured in the lower culture chamber and MVECs were cultured in the upper culture chamber. YAMCs in the lower chamber were infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b to produce rVEGF164b and TEER of MVECs in the upper chambers were compared to transwell dishes in which YAMCs were untreated or transwell dishes in which YAMCs were infected with a control adenovirus expressing GFP (Ad5-CMV-GFP). As shown in figure 5B, the addition of VEGF-A to the upper chamber significantly decreased the resistance of MVEC monolayers co-cultured with uninfected YAMCs or MVEC monolayers co-cultured with YAMCs pre-infected with Ad5-CMV-GFP. Pre-infection of YAMCs with either adenovirus alone (Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b or Ad5-CMV-GFP) in the lower chambers had no detectable effect on permeability of MVEC monolayers in the upper chambers. Interestingly, when YAMC cells in the lower chamber were pre-infected Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b, there was a significant inhibition of VEGF-A induced permeability when VEGF-A was added to MVECs in the upper chamber at 48 h post-infection. The results of this experiment show that rVEGF164b produced in YAMCs infected with Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b, can act in a paracrine fashion and inhibit the barrier disrupting activity of pro-angiogenic VEGF-A on MVECs.

Cytoskeleton reorganization

F-actin reorganization is one of the first and most prominent phenotypic changes observed in endothelial cells upon treatment with pro-angiogenic VEGFs (22). Actin reorganization precedes cell migration and increases in permeability and is VEGFR-2 mediated activating among others p38, FAK, and paxillin. We reasoned if rVEGF164b could block proliferation and barrier change, then actin reorganization would also be affected. To determine changes in actin structure MVECs were examined by fluorescence microscopy using rhodamine phalloidin staining of actin stress fibers. Untreated control cells showed a circular band of fine multiple microfilaments (figure 6 Aa), with a fluorescence staining pattern of stress fibers that was enhanced around the cell border. Upon treatment with VEGF-A, we observed a reorganization of actin filaments at 45 min, reflected by a pronounced formation of stress fibers around the periphery of the cell (figure 6 Ab). In addition, cells treated with VEGF-A showed an increase in gaps in the monolayer, which is correlative with an increase in permeability observed in the previous TEER experiments. Importantly, cells treated with rVEGF164b alone (figure 6 Ac) or cells co-treated with VEGF-A and rVEGF164b (figure 6 Ad) showed an actin staining pattern that closely resembled control untreated cells.

Figure 6.

(A) Rhodamine phalloidin staining of confluent MVECs after 45 min. treatment with (a) vehicle, (b) VEGF-A, (c) rVEGF164b, or (d) co-treatment with rVEGF164b and VEGF-A. Apparent gaps are marked by arrows (white). Each image is representative of three separate experiments. (B) ZO-1 immunofluorescence staining of confluent MVECs after 2 h treatment with (a) vehicle, (b) VEGF-A, (c) rVEGF164b, or (d) co-treatment with rVEGF164b and VEGF-A. Each image is representative of four separate experiments. (C) Transwell migration assay of MVECs in which VEGF-A induced significant migration across insert membranes and rVEGF164b inhibited this chemotactic effect while no protective effect was seen in GFP contols n=3. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Significance was determined by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05. (D) MVECs were allowed to grow to confluence in 96 well dishes at which time growth medium was switched to starvation medium for 48 hours. Cell monolayers were wounded with the point of a 1000μL pipette tip and the starvation medium was removed and replaced with experimental media and allowed to migrate for 18 h. Percent wound closure was calculated and statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with Dunnett's post test. Bars are ± SEM, n=4. *p<0.01.

ZO-1 immunostaining

ZO-1 forms a complex with numerous cytoplasmic and membrane associated proteins that form functional barriers in endothelial cells and appears as a continuous belt around the edges of the cell in normal confluent endothelial cells (23). Removal of ZO-1 from cellular junctions has been shown to have a detrimental effect on the ability of endothelial cells to form a functional barrier. In the experiment shown in Figure 6, we observed there was notable loss of ZO-1 staining at the cell to cell junctions in VEGF-A treated cells (figure 6 Bb) that was present in control untreated cells (figure 6 Ba). However, rVEGF164b treatment alone had no effect on ZO-1 staining (figure 6 Bc) compared with control untreated cells. Importantly, co-treatment with conditioned medium containing rVEGF164b prevented the loss of ZO-1 staining mediated by VEGF-A (figure 6 Bd). This result supports the previous experiments demonstrating the loss of intracellular barrier function by VEGF-A treatment.

rVEGF164b inhibits VEGF-A induced migration

VEGF-A induced migration of endothelial cells mediated by VEGFR2 is an important process in the creation of new vessel growth in inflammation and tumor growth 24. In human models, VEGF-165b inhibits HUVEC migration towards VEGF-A. Here we show that rVEGF164b has the same effect on mouse endothelial cells 25. In a VEGF-A induced transwell migration assay, VEGF-A increased endothelial migration from 27.7 ± 5.0 to 45.2 ± 6.6 cells per field (figure 6 C). rVEGF164b reduced the numbers of migrating cells back to 28 ± 3.6 cells (not sig. vs. control). This suggests that rVEGF164b blocks VEGF-A directed in vivo angiogenesis under normal and pathological states (such as inflammation and tumor growth). We performed additionally scratch wounding assays and the data from these experiments supported the findings of the transmigration assay. VEGF-A increased basal wound closure from 36.32 ± 2.58% in control to 48.43 ± 2.12%. rVEGF164b had no effect on wound closure (36.32 ± 1.64%) not different from control and inhibited VEGF-A mediated wound closure completely (33.07 ± 1.56%). This suggest and inhibition of wound repair in vivo and may have uses in hypertrophic scarring 26.

Discussion

Our results show the inhibitory VEGF expressed by Ad5-CMV-rVEGF164b, 1) can inhibit the mitogenic activity and metabolic increases mediated by VEGF-A in mouse venous endothelial cells, 2) prevent VEGF-A induced barrier disruption, 3) inhibit VEGF-A reorganization of cytoskeletal components and 4) inhibit the effects of VEGF-A on mouse endothelial cell migration. This adenoviral vector is a novel tool useful for the study of anti-angiogenic therapies in many diseases ranging from diabetic retinopathy to cancer.

Pro-angiogenic VEGFs increase proliferation rates and disrupt barrier function in endothelial cells. We demonstrated the ability of rVEGF-164b to inhibit the mitogenic effects of VEGF-A not only at equivalent concentrations but also at concentrations 10 times lower that VEGF-A concentrations (supplementary figure 1) suggesting that rVEGF164b has potent efficacy. This finding would suggest that rVEGF164b has a higher affinity for the VEGF receptors than VEGF-A however further experiments are needed to confirm this and are planned for future studies. rVEGF164b blocked VEGF-A induced MVEC proliferation, and prevented VEGF-A mediated decrease in EC barrier function in MVECs but had no effect in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in terms of proliferation (supplementary figure 2) suggesting that this inhibitory VEGF is a mouse specific isoform. Based on this discovery we conclude that subtle differences exist in the COOH terminal end of rVEGF164b that differentiates it from the human form that prevent cross reactivity. rVEGF164b blocking of VEGF-A induced MTT reduction might reflect inhibition of VEGF-A induced metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, or both.

In addition to increasing endothelial cell proliferation, VEGF-A also controls solute permeability and barrier function of micro-vessels and endothelial monolayers 27. Like endothelial proliferation, VEGF-A induced barrier dysfunction is mediated by a number of factors including signaling inputs from VEGFR-1 (Flt-1), as well as VEGFR-2 (Flk-1/KDR) 2. Unlike many receptor tyrosine kinase family members, approximately only 60% of VEGFR2 receptors are present on the cell surface. The remainder of these receptors are found in recycling compartments or in flux between intracellular and plasma membrane domains. VEGF-A binding increases VEGFR2 cycling from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane but increases degradation of activated receptors 28. Persistent blockade of VEGF-A mediated barrier disturbances by rVEGF164b is consistent with rVEGF164b inducing a shift of VEGF receptor partitioning and degradation suggesting that rVEGF164b does not alter VEGF receptor trafficking after signaling. Future studies relating VEGF receptor distribution, expression and signaling will examine this possibility. The transient loss of endothelial barrier function induced by VEGF165b has been described to be selectively mediated by VEGFR-1 27. We have not yet determined if rVEGF164b induced permeability is VEGFR-1 specific. Most importantly, we found that rVEGF164b blocked VEGF-A induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. In inflammatory states the increase in vascular permeability that is associated with VEGF signaling is a major source of edema which results in tissue damage 29. Our findings suggest that rVEGF164b may be able to prevent the increased levels of tissue edema in vivo and we are planning to examine this possibility.

rVEGF164b inhibited VEGF-A mediated F-actin rearrangement and disruption of junctional ZO-1 as seen by phalloidin staining and loss of ZO-1 immunofluorescent signal at cell to cell junctions. Tight junctions expressed in epithelial and endothelial junctional barriers contain several components including ZO-1 (zonula occludens-1) and actin microfilaments30. VEGF-A decreased ZO-1 staining between apposed endothelial cells, and was blocked by rVEGF164b. Actin filament rearrangement is also related to endothelial motility, contractility and permeability; the ability of rVEGF164b to prevent VEGF-A induced actin rearrangement suggests a possible metabolic basis underlying vascular permeability responses. rVEGF164b also reduced VEGF-A mediated chemotaxis and motility scratch (chemokinesis) wounding assays. This may suggest the ability of rVEGF164b not only to inhibit directed vessel growth in vivo but also that it may inhibit over expansion of wounded vessels in situations such as hypertrophic scaring in which defects including angiogenic repair lead to improper formation and over deposition of tissue at the wound. These findings are by parallel changes in actin microfilaments induced by VEGF-A and inhibited by rVEGF164b (supplementary figure 3).

This study shows that rVEGF164b inhibits VEGF-A induced proliferation and barrier disruption in MVECs in a manner comparable to what has been reported for the human inhibitory VEGF165b isoform. These findings are significant since these effects can result in the inhibition of formation of new vessels and vessel leakage in vivo. Excessive vessel formation and permeability are key markers of inflammation, and correlate to the pathogenesis of many diseases 5. Like the human VEGF165b isoform, rVEGF164b alters the barrier function of vascular ECs monolayers. This effect is mediated through VEGFR-1 in humans; however, we have not yet determined if the effects of rVEGF164b are mediated by either VEGFR-1 or VEGF-2, or heterodimers of both receptors 27. These data reflect results using ECs of venous origin and may vary depending on the origin of the EC used because ECs are not homogenious and vary depending on origin. Future studies are necessary to determine if the effect of this and other inhibitory VEGFs are similar or different in the context of endothelial cells from arterial or capillary origin.

Supplementary Material

rVEGF164b can inhibit VEGF-A induced proliferation as measured by MTT uptake at concentrations 10× lower than VEGF-A suggesting greater affinity for receptors. Bars are means ± SEM and results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test

HUVECs were plated at 10% density and treated with 50ng/mL VEGF-A, 50ng/mL rVEGF164b, a combination of the two or control media. Cells were allowed to proliferate for 24 h at which time the experimental media was removed and MTT assay was performed. Unlike the effect in MVECs rVEGF164b did not significantly inhibit the effects of VEGF-A on MTT uptake in HUVECs suggesting specificity of this isoform. Bars are means ± SEM and results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test

(A) TEER of MVEC monolayers that were pretreated with rVEGF164 or VEGF-A followed by a spike of VEGF-A at 40 min post treatment to determine durability of inhibition of VEGF-A mediated decrease in TEER. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Protection was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6. (B) Monolayers of MVECs treated with rVEGF164b followed by a spike of VEGF-A at 150 min post treatment to show time inhibiton of VEGF-A mediated decrease in TEER. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Protection was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. **p < 0.01, n = 3.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like thank the following persons for their contributions to this body of work: Dr. Vijay Ganta for his research insight, Ms. Shannon Wells for her technical assistance, Dr. Christopher Kevil for his technical expertise, and Dr. Jenifer Fenton for her kind gift of the YAMC cell line. This work was supported, in part, by: the Louisiana Gene Therapy Research Consortium; the Feist-Weiller Cancer Center at LSU Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, LA the American Heart Association; and the National Institutes of Health (grant 5P01DK043785).

References

- 1.Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, et al. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64(21):7822–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):359–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleton I, Brown NJ, Willis D, Colville-Nash PR, Alam C, Brown JR, Willoughby DA. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in a murine chronic granulomatous tissue air pouch model of angiogenesis. J Pathol. 1996;180(1):90–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199609)180:1<90::AID-PATH615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ten Brick Robin A, C DT, Martin Jeremy L, Moline Karl V, Bergman Jeffery W, Cupp Andrea S. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Inhibitory Isoform Is Regulated Prior to Ovulation. Nebraska Beef Cattle Reports. 2007;1(1):113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usui T, Ishida S, Yamashiro K, Kaji Y, Poulaki V, Moore J, Moore T, Amano S, Horikawa Y, Dartt D, et al. VEGF164(165) as the pathological isoform: differential leukocyte and endothelial responses through VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(2):368–74. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kevil CG, De Benedetti A, Payne DK, Coe LL, Laroux FS, Alexander JS. Translational regulation of vascular permeability factor by eukaryotic initiation factor 4E: implications for tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1996;65(6):785–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960315)65:6<785::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen YH, Wu HL, Chen CK, Huang YH, Yang BC, Wu LW. Angiostatin antagonizes the action of VEGF-A in human endothelial cells via two distinct pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310(3):804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharpfenecker M, Fiedler U, Reiss Y, Augustin HG. The Tie-2 ligand angiopoietin-2 destabilizes quiescent endothelium through an internal autocrine loop mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 4):771–80. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iruela-Arispe ML, Porter P, Bornstein P, Sage EH. Thrombospondin-1, an inhibitor of angiogenesis, is regulated by progesterone in the human endometrium. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(2):403–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI118429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambati BK, Patterson E, Jani P, Jenkins C, Higgins E, Singh N, Suthar T, Vira N, Smith K, Caldwell R. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 contributes to the corneal antiangiogenic barrier. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(4):505–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.107417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, Kleinman ME, Dridi S, Takeda A, Baffi JZ, Yamada K, Kaneko H, Green MG, et al. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62(14):4123–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowak DG, Woolard J, Amin EM, Konopatskaya O, Saleem MA, Churchill AJ, Ladomery MR, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Expression of pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF is differentially regulated by splicing and growth factors. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 20):3487–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Perrin RM, Raffy S, Dixon AR, Paraskeva C, Zaccheo O, Hassan AB, et al. VEGF 165 b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(8):1366–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ando T, Jordan P, Joh T, Wang Y, Jennings MH, Houghton J, Alexander JS. Isolation and characterization of a novel mouse lymphatic endothelial cell line: SV-LEC. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3(3):105–15. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2005.3.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obinata M. Conditionally immortalized cell lines with differentiated functions established from temperature-sensitive T-antigen transgenic mice. Genes Cells. 1997;2(4):235–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1160314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang GY, Xu B, Hashimoto T, Huey M, Chaly T, Jr, Wen R, Young WL. Induction of focal angiogenesis through adenoviral vector mediated vascular endothelial cell growth factor gene transfer in the mature mouse brain. Angiogenesis. 2003;6(2):151–8. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000011803.56605.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhlhauser J, Merrill MJ, Pili R, Maeda H, Bacic M, Bewig B, Passaniti A, Edwards NA, Crystal RG, Capogrossi MC. VEGF165 expressed by a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus vector induces angiogenesis in vivo. Circ Res. 1995;77(6):1077–86. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conn G, Soderman DD, Schaeffer MT, Wile M, Hatcher VB, Thomas KA. Purification of a glycoprotein vascular endothelial cell mitogen from a rat glioma-derived cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(4):1323–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennel E, Waine E, Guan H, Schuler Y, Leenders W, Woolard J, Sugiono M, Gillatt D, Kleinerman E, Bates D, et al. The endogenous anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform, VEGF165b inhibits human tumour growth in mice. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(7):1250–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright GL, Maroulakou IG, Eldridge J, Liby TL, Sridharan V, Tsichlis PN, Muise-Helmericks RC. VEGF stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis: requirement of AKT3 kinase. Faseb J. 2008;22(9):3264–75. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-106468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousseau S, Houle F, Kotanides H, Witte L, Waltenberger J, Landry J, Huot J. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-driven actin-based motility is mediated by VEGFR2 and requires concerted activation of stress-activated protein kinase 2 (SAPK2/p38) and geldanamycin-sensitive phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(14):10661–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Itallie CM, Fanning AS, Bridges A, Anderson JM. ZO-1 Stabilizes the Tight Junction Solute Barrier through Coupling to the Perijunctional Cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkefors I, Le Jan S, Jakobsson L, Hejll E, Carlson G, Johansson H, Jarvius J, Park JW, Li Jeon N, Kreuger J. Endothelial cell migration in stable gradients of vascular endothelial growth factor A and fibroblast growth factor 2: effects on chemotaxis and chemokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(20):13905–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnussen AL, C A, Harper S, Floege J, Bates D. VEGF165b is more potent at inhibiting endothelial cell migration than Pegabtanib and is cytoprotective for retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Faseb J. 2008;22(746.14):746. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song B, Lu K, Zhang Y, Guo S, Han Y, Ma F, Li H. Angiogenesis in hypertrophic scar of rabbit ears and effect of extracellular protein with metalloprotease and thrombospondin 1 domains on hypertrophic scar. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;22(1):70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass CA, Harper SJ, Bates DO. The anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform VEGF165b transiently increases hydraulic conductivity, probably through VEGF receptor 1 in vivo. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):243–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott A, Mellor H. VEGF receptor trafficking in angiogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 6):1184–8. doi: 10.1042/BST0371184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spyridopoulos I, Luedemann C, Chen D, Kearney M, Chen D, Murohara T, Principe N, Isner JM, Losordo DW. Divergence of angiogenic and vascular permeability signaling by VEGF: inhibition of protein kinase C suppresses VEGF-induced angiogenesis, but promotes VEGF-induced, NO-dependent vascular permeability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(6):901–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000020006.89055.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li CX, Poznansky MJ. Characterization of the ZO-1 protein in endothelial and other cell lines. J Cell Sci. 1990;97(Pt 2):231–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rVEGF164b can inhibit VEGF-A induced proliferation as measured by MTT uptake at concentrations 10× lower than VEGF-A suggesting greater affinity for receptors. Bars are means ± SEM and results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test

HUVECs were plated at 10% density and treated with 50ng/mL VEGF-A, 50ng/mL rVEGF164b, a combination of the two or control media. Cells were allowed to proliferate for 24 h at which time the experimental media was removed and MTT assay was performed. Unlike the effect in MVECs rVEGF164b did not significantly inhibit the effects of VEGF-A on MTT uptake in HUVECs suggesting specificity of this isoform. Bars are means ± SEM and results were analyzed by ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test

(A) TEER of MVEC monolayers that were pretreated with rVEGF164 or VEGF-A followed by a spike of VEGF-A at 40 min post treatment to determine durability of inhibition of VEGF-A mediated decrease in TEER. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Protection was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 6. (B) Monolayers of MVECs treated with rVEGF164b followed by a spike of VEGF-A at 150 min post treatment to show time inhibiton of VEGF-A mediated decrease in TEER. Bars are means ± SEM of three independent measurements. Protection was determined by repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. **p < 0.01, n = 3.