Abstract

Chloroplast membranes contain a substantial excess of the nonbilayer-prone monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (GalDAG) over the biosynthetically consecutive, bilayer-forming digalactosyldiacylglycerol (GalGalDAG), yielding a high membrane curvature stress. During phosphate shortage, plants replace phospholipids with GalGalDAG to rescue phosphate while maintaining membrane homeostasis. Here we investigate how the activity of the corresponding glycosyltransferase (GT) in Arabidopsis thaliana (atDGD2) depends on local bilayer properties by analyzing structural and activity features of recombinant protein. Fold recognition and sequence analyses revealed a two-domain GT-B monotopic structure, present in other plant and bacterial glycolipid GTs, such as the major chloroplast GalGalDAG GT atDGD1. Modeling led to the identification of catalytically important residues in the active site of atDGD2 by site-directed mutagenesis. The DGD synthases share unique bilayer interface segments containing conserved tryptophan residues that are crucial for activity and for membrane association. More detailed localization studies and liposome binding analyses indicate differentiated anchor and substrate-binding functions for these separated enzyme interface regions. Anionic phospholipids, but not curvature-increasing nonbilayer lipids, strongly stimulate enzyme activity. From our studies, we propose a model for bilayer “control” of enzyme activity, where two tryptophan segments act as interface anchor points to keep the substrate region close to the membrane surface. Binding of the acceptor substrate is achieved by interaction of positive charges in a surface cluster of lysines, arginines, and histidines with the surrounding anionic phospholipids. The diminishing phospholipid fraction during phosphate shortage stress will then set the new GalGalDAG/phospholipid balance by decreasing stimulation of atDGD2.

Keywords: Glycolipids, Lipid, Membrane Bilayer, Membrane Enzymes, Membrane Lipids, Plant, Tryptophan, Glycosyltransferase, Molecular Modeling

Introduction

At least 30% of the genes in most cells encode proteins that are associated with the surface or embedded in the lipid matrix of the membranes, either as peripheral or as integral membrane proteins (1). Lipids form a bulk bilayer with certain properties and can interact specifically with sites in certain membrane proteins or complexes, potentially as structural cofactors. Hence, lipids exert a substantial control over the activity of many proteins or assist protein-protein interactions. A key characteristic of plants and photosynthetic bacteria is the high abundance of galactolipids in their membranes harboring the photosynthetic complexes. Analogous glycolipids are major components in many Gram-positive bacteria. Most are uncharged, consisting of a glycerol backbone esterified with two acyl chains and carrying one (monoglycosyldiacylglycerol) or two (diglycosyldiacylglycerol) sugar moieties in the headgroup. They are prone to interact by hydrogen bonding, and pure monoglycosyl-DAGs3 tend to form nonbilayer aggregates due to their small headgroups, whereas diglycosyl-DAGs are always bilayer-forming. Their relative amounts will affect spontaneous curvature and hence the lateral stress profile of the bilayer (2, 3). The predominant glycolipid class in photosynthetic organisms is generally GalDAG, whereas glycolipid species and sugar types vary in bacteria.

Several enzymes involved in the pathways of glycolipid biosynthesis in bacteria and higher plants have been identified and described recently. The complex route in higher plants is catalyzed by three GalDAG synthases (MGDs) and two GalGalDAG synthases (DGDs), which all belong to the group of UDP-Gal-dependent glycosyltransferases (GTs) and are localized in the chloroplast envelopes (4). In contrast, in most Gram-positive bacteria, only one homolog of each monoglycosyl-DAG and diglycosyl-DAG synthase activity is present, such as in the small Acholeplasma laidlawii (named alMGS and alDGS), which are both UDP-Glc-dependent glycosyltransferases (5). Previous studies have shown that these two consecutively acting enzymes are completely under the control of the packing and surface charge properties of their host membrane lipid bilayers (6), displaying a robust mechanism for membrane homeostasis; by so-called feedback loops, they sense and then control the bilayer curvature and surface charge by synthesizing lipids of suitable properties for the prevailing environmental conditions at hand (7).

Several stress conditions seem to affect plant galactolipid composition. Under optimal growth conditions, the galactolipids are restricted to the chloroplast, the precursors being either of entirely chloroplastic origin (prokaryotic pathway) or reimported via the endoplasmic reticulum (eukaryotic pathway). However, GalGalDAG also accumulates in extraplastidial membranes during phosphate starvation. GalGalDAG synthesis (from GalDAG) takes place in the outer envelope of the plast, with atDGD1 representing the major activity (90%) in Arabidopsis thaliana and atDGD2 contributing the remaining 10% of the GalGalDAG during normal growth conditions. In order to deal with fluctuating phosphate availability, higher plants and some bacteria have developed various strategies to ensure phosphate availability for critical functions, such as providing phosphate by the breakdown of phospholipids during phosphate-limiting conditions (8). The non-phosphorous lipids GalGalDAG and sulfoquinovosyl-DAG are increased to act as surrogate lipids because they also belong to the bilayer-forming lipid classes similar to most of the major phospholipids. Transcription of both DGD genes is strongly induced during phosphate starvation conditions, and it has been demonstrated that the atDGD2 enzyme is a key player of synthesis of extraplastidial GalGalDAG under phosphate starvation. Together with atMGD2 and atMGD3, atDGD2 forms the DGD1-independent pathway in A. thaliana, which is especially active in roots. GalGalDAG synthesis is also triggered in non-photosynthetic tissue, such as the nitrogen-fixing nodules of soybean and lotus (9), where it serves as a membrane component of the peribacteroid membrane.

It is well accepted that maintaining a certain bilayer curvature stress is the underlying reason for most of the observed changes in galactolipid composition because curvature is a key factor for cell homeostasis and is heavily involved in protein-mediated membrane processes (2, 3, 10, 11). The ratio of bilayer/nonbilayer-prone lipids (i.e. here the GalGalDAG/GalDAG ratio), will strongly affect curvature and phase equilibria, which in turn affect functional features of the membrane proteins (3, 12, 13). Nitrogen deficiency (14, 15) and drought tolerance (16) lead to an increased GalGalDAG/GalDAG ratio, and consequently the bilayer spontaneous curvature must be decreased. Also, a number of Arabidopsis mutants have been described that are impaired in adjusting their galactolipid profile in response to a changed temperature, such as acquiring thermotolerance (heat stress) (17, 18) by increasing the amount of GalGalDAG or in galactolipid remodeling by synthesizing oligogalactolipids (with three or more galactose moieties as headgroup) during freezing (and dehydration) conditions (19). The importance of spontaneous curvature for photosynthesis was also revealed in a suppressor mutant with an increased saturation rate and therefore altered packing shape of GalDAG (20), which could compensate for the impaired photosynthetic capacity of an Arabidopsis mutant at low temperature.

Glycosyltransferases are currently divided into 92 families in the CAZy database, largely on the basis of amino acid sequence similarities (see the CAZy Web site). The majority of these adopt either a single (GT-A) or a double (GT-B) Rossmann-like fold structure, the latter organized in two domains (the N and C domains) (21). It seems that most membrane GTs synthesizing major glycolipids are of the larger GT-B organization type (22–24). Many of these lack transmembrane segments and are anchored in the membrane interface by charge and hydrophobic interactions, qualifying as monotopic membrane proteins (25). The membrane-associated species seem to be enriched in positively charged residues, especially in their N domains, yielding high calculated pI values (24, 26). Amphiphilic helices are also implicated in interface binding (24, 26). The number of Trp residues, frequently involved in membrane binding, varies substantially between species, potentially in relation to the frequency of positively charged amino acid (aa) pairs; one extreme is alMGS with only one Trp but with many plus pairs (24). These features are believed to be involved in anchoring the enzymes to specific lipid environments and also influence their activities. This has been observed for the joint activities of the regulatory A. laidlawii alMGS and alDGS enzymes, controlling lipid curvature and charge (7). Likewise, the activities of the membrane lipid glycosyltransferases in Mycoplasma pneumoniae (27) and Bacillus subtilis (28) are affected by the local lipid environment and hence involved in adaptation to membrane lipid composition.

Our aims here are to establish structural features for the GT enzymes that govern their activity in the curvature-critical biosynthetic step between the major nonbilayer-prone GalDAG and bilayer GalGalDAG lipids in A. thaliana. This balance is present in all photosynthetic organisms and is of high importance for bilayer properties and associated reactions, and it becomes especially apparent when plants are exposed to phosphate deficiency conditions. As a comparison, we used the established curvature regulation between GlcDAG and GlcGlcDAG in A. laidlawii by the alDGS enzyme, which belongs to the same GT-4 sequence family in the CAZy systematics. The two enzymes were found to have a similar three-dimensional organization, which was associated with a membrane interface, but the A. thaliana enzyme responded only to lipid charge conditions and not to the spontaneous curvature.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Synthetic rac-1,2-dioleoylglycerol (DOG), l-α-phosphatidylserine (PS; spinal cord, bovine), and l-α-phosphatidylinositol (yeast) were purchased from Larodan Fine Chemicals (Malmo, Sweden). Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidic acid, dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), and dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DOPG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. 2-(4,4-Difluoro-5,7-diphenyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-pentanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (β-BODIPY® 530/550 C5-HPC) was purchased from Invitrogen. Uridine diphospho-d-[U-14C]galactose and -glucose were obtained from GE Healthcare. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was obtained from Saveen-Werner. GalDAG (plant leaf) was purchased from Lipid Products (UK), whereas GlcDAG (Escherichia coli) and GalDAG (E. coli) were isolated from E. coli strains, which had been transformed with vectors harboring A. laidlawii MGS and A. thaliana MGD1, respectively (29). All other reagents were of the highest grade available.

Construction of Wild-type and Mutant Expression Vectors for atDGD2 and alDGS

All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S3. Constructs and introduced mutations were confirmed by sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon). Both the A. thaliana pQE31-DGD2 construct (30) and the A. laidlawii pET15b-alDGS construct (5), served as templates to introduce the desired mutations using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For protein expression, the mutated versions of the pQE31-DGD2 and pET15b-alDGS were transformed into E. coli M15pREP4 and E. coli BL21 StarTM (DE3) pLysS cells, respectively. A full-length DGD2-GFP fusion construct was generated by fusing the GFP C-terminally to DGD2 (31). A GFP expression vector was generated by modifying the pET43.1b vector as follows. The ORF of the nusA gene was replaced via NdeI and SacII by the GFP-ORF, which had been amplified using the oligonucleotides PAK53 and PAK54. The resulting vector was then used to obtain fusion proteins of selected atDGD2 segments carrying an N-terminal GFP tag for localization as well as a C-terminal His tag to enable purification by Ni2+ affinity chromatography (cf. below).

Construction of Wild-type and Mutant Expression Vectors for Selected atDGD2 Segments

DNA oligonucleotide pairs encoding the desired segments (both WT and mutated versions) with overlapping ends encoding restriction sites were synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Germany). Initially, four oligonucleotides coding for the same segment (0.15 nm each) were mixed in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and 10 mm MgCl2, heated for 5 min at 95 °C, and subsequently cooled down to room temperature. The assembled oligonucleotide pairs were then ligated into XmaI and HindIII sites of the modified pET43.1b-GFP(+) vector. Finally, these constructs were transformed into E. coli (BL21 StarTM(DE3) pLysS) for recombinant protein expression.

Recombinant Protein Expression and Preparation of Wild-type and Mutant Glycosyltransferases for in Vitro Assay

Unless otherwise stated, all E. coli strains harboring the various constructs compared in a given experiment were grown under the same conditions. 15 ml of 2× LB supplemented with appropriate antibiotics were inoculated with 150 μl of an overnight culture and grown at 37 °C until A600 reached 0.4. Recombinant protein production was then induced with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside followed by a 4-h incubation, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 × g, and pellets were stored at −20 °C. Crude protein extracts from each clone were prepared by resuspending the pellets in 1.5 ml of 0.1 m HEPES (pH 8.0), breaking the cells by adding 70 μl of lysozyme (30 mg/ml) and 50 μl of DNase I (30 μg/ml), followed by 20 min of incubation at room temperature. These samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 20,000 × g, supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of buffer (50 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 15 mm CHAPS, 1 mm DTT, 10% glycerol, 10 mm MgCl2) and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined by using the QuikStartTM solution (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer's protocol; protein bands were visualized by staining the gel with PageBlueTM protein staining solution (Fermentas).

In Vitro Assays for Recombinant and Wild-type and Mutant Glycosyltransferases

Assays in mixed micelles were technically performed as described (6) with slight modifications. Mixed micelles were prepared by mixing lipids solubilized in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) to the required concentrations (for a standard GalGalDAG or GlcGlcDAG synthase assay, 200 nmol of DOPC, 250 nmol of DOPG, and 50 nmol of Gal- or GlcDAG), and the solvent was evaporated under an N2 stream. Lipid mixtures were then solubilized to homogeneity in a CHAPS-based assay buffer (50 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 10 mm MgCl2, 35 mm CHAPS, 10% glycerol) by extensive vortexing, followed by water bath sonification for 5 min. 20 μl of E. coli protein extracts (corresponding to ∼20 μg of total protein) were added to 20 μl of mixed micelles, and reactions were started by adding 2.5 μl of assay buffer (200 mm MOPS, pH 7.8, 40 mm MgCl2, 40% glycerol), 2 μl DTT (25 mm as final concentration), 3.5 μl H2O, and 2 μl of UDP-[14C]galactose (50 nCi) and incubating for 45 min at 30 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 400 μl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) and 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl, lipids were then extracted and separated by TLC as described (32) and subsequently quantified using the FUJIFILM FLA-3000 Image Reader. All enzymatic assays were done at least in duplicate. Kinetic parameters for recombinant atDGD2 protein with different substrates were determined as described above except for using atDGD2 protein purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography.

Expression and Purification of atDGD2 Wild-type and Mutated Segments

E. coli (BL21 StarTM(DE3) pLysS) cells harboring the GFP-fused atDGD2 19-aa segments were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C until the A600 reached 0.4, expression was induced with 0.4 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h, and bacteria cells were harvested by centrifugation for 15 min at 3000 × g at 4 °C. Bacterial pellets were initially resuspended in lysis buffer (100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 50 mm NaCl, 50 mm KAc, 10% glycerol) containing 1 mm MgCl2, 200 μg/ml lysozyme, 20 μg/ml DNase I, 1 mm PMSF, and 1 m urea for 25 min at room temperature and were then broken by means of a French press. The suspension containing target proteins was subsequently cleared by ultracentrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min. Imidazole (20 mm final concentration) was added to the lysate, which was then loaded onto a HisTrapTMHP column (GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed with 20 column volumes of washing buffer (100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol) at a 1 ml/min flow rate; the target protein was then eluted with elution buffer (100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol). Purified peptides were stored at 4 °C until use after the addition of NaN3 (0.1% final concentration).

Liposome Binding Assay for atDGD2 Wild-type and Mutant Segments

Lipids solubilized in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) were mixed to contain 50% DOPC (mol/mol) and 50% DOPG; 50% DOPC and 50% l-α-phosphatidylinositol; 50% DOPC and 50% PS; 70% DOPC and 30% CL; 45% DOPC, 10% DOPG, and 45% DOPE (or GalDAG); or 70% DOPC and 30% cardiolipin. β-BODIPY® 530/550 C5-HPC was added to each lipid mixture as an internal standard (0.1 mol %). The solvent was evaporated under a stream of N2 and then stored under vacuum overnight to remove traces of organic solvents. The dried lipid films were resuspended in liposome buffer (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.4) containing sucrose (176 mm) to a final concentration of 1 mm total lipid. Large unilamellar vesicle solution was produced by forcing the suspension 21 times through two layers of polycarbonate membranes with a 100-nm pore size within a Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). Finally, the solution outside the sucrose-loaded large unilamellar vesicle solution was exchanged for liposome buffer. Liposomes were stored at +4 °C until use. The binding of the various atDGD2-GFP fusion peptides to sucrose-loaded liposomes was measured using the ultracentrifugation technique described previously (33). The sucrose-loaded liposomes (0.5 mm total lipid) were mixed with the purified peptides at a peptide/lipid ratio of 1:500 (mol/mol) in a total volume of 100 μl of liposome buffer for 15 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to NuncTM 96-well plates for fluorescence measurement. The pellet was first resuspended into 100 μl of liposome buffer containing 0.01% Triton X-100 and then also transferred to NuncTM 96-well plates for fluorescence measurement. GFP fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 390 nm, emission wavelength of 530 nm, and a 495-nm cut-off filter. β-BODIPY® fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 530 nm, emission wavelength of 560 nm, and a 550-nm cut-off filter in a SpectraMaxGemini EM (Molecular Devices). The amounts of proteins and lipids were quantified both in the supernatant and pellet to evaluate the percentage of peptides bound to liposomes.

Lipid Binding Assay for atDGD2 Wild-type and Mutant Segments

PIP StripsTM (Echelon Biosciences Inc.) were first blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4 mm Na2HPO4, 6.65 mm KH2PO4) containing 1% nonfat dry milk and gently agitated for 1 h at room temperature, and then atDGD2-GFP fusion segments (2.0 μg/ml) were added in PBS buffer containing 1% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times in PBS-T (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4 mm Na2HPO4, 6.65 mm KH2PO4, 0.1% Tween 20), atDGD2-GFP peptides associating with the lipid strips were visualized by immunodetection, first incubating the PIP StripsTM with penta-His antibody (Qiagen; 1:2000 dilution in PBS buffer containing 1% nonfat dry milk) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three 5-min washes. The lipid strips were then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody in the same buffer for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three 5-min washes with PBS-T. The Amersham Biosciences ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare) was used to detect the HRP-coupled antibodies, and a FUJIFILM image reader LAS-1000 Pro was used for image capture.

Fluorescence Microscopy

E. coli cells harboring atDGD2 wild-type and mutated segments were grown in LB medium overnight and then mixed 1:1 (v/v) with 1% low melting agarose on the microscopy slides. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 (FITC filter) fluorescence microscope. Images were captured with a CCD camera equipped with Image Access 3.0 software (Imagic Bildverarbeitung AG) and edited in Adobe®Photoshop 9.

Bioinformatic Methods

For phylogenetic tree construction, multiple alignments of the selected amino acid sequences (see supplemental Fig. S2) were performed using the software ClustalW2 (34), and a phylogenetic tree was then obtained by the built-in phylogram. Full-length sequences encoding DGD synthases were obtained through BLAST from NCBI as well as from the Selaginella Genomics database (available from the Joint Genome Institute of the U.S. Department of Energy on the World Wide Web). Database sequence accession numbers of the orthologs identified in the various organisms are as follows (in parentheses): A. thaliana atDGD1 (NP_187773) and atDGD2 (NP_191964); Glycine max gmDGD1 (Q6DW76.1) and gmDGD2 (Q6DW75.1); Ricinus communis rcDGD1 (XP_002533901.1) and rcDGD2 (XP_002511814.1); Lotus japonicus ljDGD1 (Q6DW74.1) and ljDGD2 (Q6DW73.1); Populus trichocarpa ptDGD1 (XP_002323386.1) and ptDGD2 (XP_002320779.1); Vitis vinifera vvDGD1 (XP_002264659.1) and vvDGD2 (XP_002266316.1); Zea mays zmDGD1 (NP_001152532.1) and zmDGD2 (ACN27450.1); Chlamydomonas reinhardtii crDGD1 (XP_001693597.1); Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ssDGS (NP_441335.1); Chloroflexus aurantiacus caDGS (YP_001634281); Selaginella moellendorffii smDGD1 (jgi|Selmo1|130585|); Anabaena variabilis avDGS (YP_321246.1); Ostreococcus tauri otDGD1 (CAL55753.1) and otDGD2 (CAL54570.1); Physcomitrella patens ppDGD1 (XP|001761588) and ppDGD2 (XP_001770278); Oryza sativa osDGD1 (ABA91566.1) and osDGD2 (NP_001049371.1); Acholeplasma laidlawii alDGS (YP_001620527.1); Micromonas pusilla mpDGD1 (EEH54171.1) and mpDGD2 (EEH60236.1). N-terminal sequences upstream of the core glycosyltransferase region were removed prior to alignment and phylogenetic tree construction.

For comparing structural similarities, six monotopic proteins with GT-B fold and experimental confirmation of membrane (or lipid bilayer) localization were selected. Of them, PimA (Protein Data Bank entry 2GEK (35)), GumK (Protein Data Bank entry 2Q6V (36)), and MurG (Protein Data Bank entry 1F0K (37)) with established three-dimensional structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. The structural models of atDGD1, atDGD2, and alDGS were based on the sequence alignments and fold recognition provided by the MetaServer (38) (available on the World Wide Web) and generated by using the Swiss-PdbViewer (39) and SWISS-MODEL (40, 41) programs for alignment and modeling together with WhatCheck (42) for model validation, as described (5).

Docking of the UDP-Gal or UDP-Glc molecules into the proposed active sites of atDGD2 or alDGS model structures was guided by two protein-ligand complexes involving proteins with a GT-B architecture (Protein Data Bank entries 2ACW and 1NLM), followed by a slow cooling simulated annealing molecular dynamics protocol using the program X-PLOR (43) with the force field toph19.pro/param19.pro. Parameter and topology files were generated by the PRODRG2 server (44) (available on the World Wide Web). The program MOLMOL (45) was used for model analysis and for selection of residues that are close to the ligand and potentially crucial for activity. The isoelectric points for their N and C domains according to structures and fold recognition were calculated.

Surface electrostatic potentials were prepared and calculated using the PDB 2PQR (46) and APBS (47) programs, and surface representations were illustrated with PyMOL (DeLano Scientific, LLC). The surface is colored by relative electrostatic potential (obtained by using the APBS plug-in in PyMOL), with red and blue denoting negatively and positively charged surfaces, respectively. MPEx (Membrane Protein Explorer) (48) (available on the World Wide Web) was adopted to predict the most likely membrane interface association segments of a given protein sequence based on the built-in interface scale mode and calculate the hydrophobic moment of the segments. Potential transmembrane helices were predicted by TMHMM (available on the World Wide Web).

RESULTS

Phylogenetic Analysis of atDGD1 and atDGD2 Enzymes

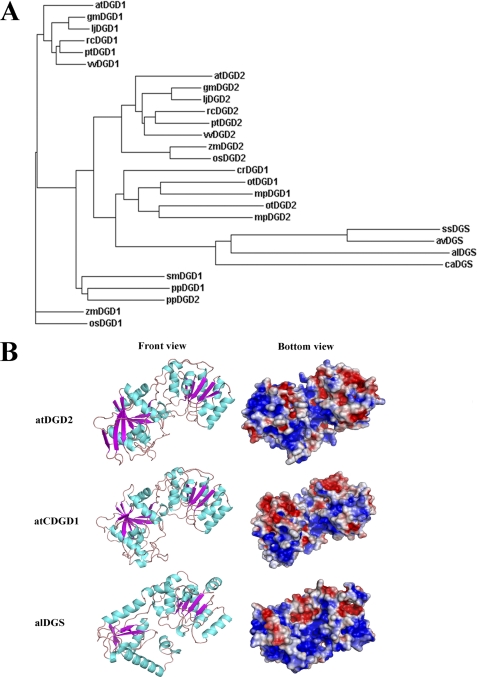

Glycosyltransferases are present in all organisms with a few very conserved structures. To establish a possible evolutionary relationship between the A. thaliana DGD1 and DGD2 enzymes, we performed a BLAST search for enzymes with either established or predicted GalGalDAG synthase activity. Sequences encoding full-length proteins from selected organisms were used for sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses. The bacterial GalGalDAG synthases are all composed of the core GT sequence and are named DGS here. Two types of plant GalGalDAG synthases exist: DGD1, which consists of a large N-terminal extension (N-DGD1), and the core GT-B part (C-DGD1), and DGD2, which lacks this extra N-terminal domain and consists of only the main GT region. The N-terminal domains of the selected DGD1 sequences were removed in the phylogenetic analyses because they are not present in DGD2 proteins or any of the bacterial orthologs and would have distorted the results.

The phylogram in Fig. 1A (of which the corresponding alignment is shown as supplemental Fig. S1) clearly shows that “lower” organisms possess only one version of a diglycosylDAG synthase, whereas a second variant can be found in higher organisms. The alDGS homolog of Acholeplasma clusters with the cyanobacteria A. variabilis and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Also only one homolog is present in the green filamentous bacterium C. aurantiacus. Both a DGD1 and a DGD2 variant were found in O. tauri (a green unicellular alga) as well as in the marine picoeukaryote Micromonas genome. Interestingly, however, only one homolog (with a long N-terminal extension) could be identified in the green alga C. reinhardtii. Likewise, the fern S. moellendorffii also possesses only one DGD1 copy, which forms a clade with two sequences (both a DGD1 and a DGD2 variant) found in the Physcomitrella genome.

FIGURE 1.

Evolutionary relationships and structural models of A. thaliana and A. laidlawii glycolipid glycosyltransferases. A, phylogram showing the evolutionary relationship of glycosyltransferases with predicted and/or experimentally proven DGD synthase activity. Sequences (consisting only of the core GT region and lacking any N-terminal “extension” domain) were aligned using ClustalW. The corresponding alignment is shown in supplemental Fig. S1. B, GT-B folds were recognized from MetaServer fold recognition and modeling performed with SWISS-MODEL (see “Experimental Procedures”). Blue and red, positive (atDGD2, +58 aa; alDGS, +49 aa) and negative (atDGD2, −57 aa; alDGS, −37 aa) surface charge, respectively. Gray, hydrophobic residues. The bottom, potentially interface-interacting face is rotated 90° from the front view.

With regard to higher plants, all possess DGD1 as well as DGD2. The DGD2 proteins form a sister clade with the unicellular algae and moss clades, whereas the DGD1 of higher plants form a separate clade. Significantly, all identified sequences in Fig. 1A belong to CAZy GT family 4, which are supposed to have a GT-B organization and in which the anomeric configuration of the sugar bond is retained in an α orientation (49).

Fold Recognition and Structure Modeling of atCDGD1, atDGD2, and alDGS

To gain insight into potential regulatory features of the plant GalGalDAG synthases, we used an array of bioinformatic tools, including fold recognition and modeling, as done previously for A. laidlawii alDGS (5) (see “Experimental Procedures”). Analyses using the MetaServer at the Polish Bioinformatic Institute suggested established GT-B structures from several different GT families as the most similar folds for atC-DGD1, atDGD2, and alDGS, respectively. Modeling of the three DGD synthases was based on the three highest ranked unique three-dimensional templates (supplemental Table S1) and was completed by using Swiss-PdbViewer for alignments, SWISS-MODEL for modeling, and WhatCheck for subsequent model validation. For the large N-terminal extra part of DGD1 (which is not present in atDGD2), no hits with BLAST searches to established proteins and consequently no conclusive structural information could be obtained from the MetaServer.

The chosen templates, as identified from the combined and ranked MetaServer analyses, are from different but related CAZy GT sequence families, such as the glycogen synthase 1 structure from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. This structure has for several years ranked as the best candidate for atDGD2 and is a member of the GT5 family. GT5 also has an N-terminal extension compared with family GT4, which might explain why the GT5 model was chosen. Although the sequence similarities to existing three-dimensional GT structures are low (according to BLAST; supplemental Table S1), the generated models from the MetaServer and SWISS-MODEL analyses are good according to the validation procedures (supplemental Table S1). The models reveal the characteristic double Rossmann fold of the GT-B structural superfamily, with the active site located in the cleft between the two halves (see Fig. 1B). The right panel shows the potential membrane interface surface of the GTs, an orientation that must allow for binding of the bilayer-localized acceptor lipids as well as the water-soluble UDP-sugar donor substrates.

Identification of Critical Residues in the Active Sites of atDGD2 and alDGS

The involvement of atDGD2 in phosphate stress responses makes it an important candidate to study enzymatic features characteristic for plant DGD synthases. atDGD2 exhibits a much stronger activity than atDGD1 when heterologously expressed in E. coli (data not shown), despite the fact that atDGD1 is the major DGD synthase in vivo. It lacks the extra N-terminal extension present in atDGD1; nevertheless, atDGD2 does represent a fully functional GalGalDAG synthase as deduced from in vitro studies as well as Arabidopsis dgd2 mutant alleles (50). In a first effort, we challenged the quality of our atDGD2 and alDGS structure by attempting to identify the residues that are involved in the UDP-Gal or UDP-Glc (donor substrate) binding in the two DGD synthases by docking the sugar substrates into the proposed active sites. A selected set of amino acids that appeared especially close in space to the substrates (3 Å or less for atDGD2 and 4.0 Å or less for alDGS; supplemental Table S2) were mutagenized to alanine (Fig. 2A), and GalGalDAG (or GlcGlcDAG for alDGS) synthase activity of the obtained mutated proteins was assayed.

FIGURE 2.

Important amino acid residues in the active sites of atDGD2 and alDGS. A and C, the sugar donor substrates UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose (in blue) were docked into the active sites, containing the (E/D)X7E motifs of atDGD2 and alDGS, respectively (see “Experimental Procedures”). Selected residues in the close vicinity (3.5 Å or less for atDGD2 and 4.0 Å or less for alDGS) are highlighted (purple), and experimentally mutated residues are boxed. B and D, SDS-PAGE analysis of membrane proteins solubilized from E. coli cells expressing recombinant atDGD2 (left) or alDGS (right) or mutated versions of these. To measure GalGalDAG synthase or GlcGlcDAG synthase activities, equal amounts of proteins were incubated with mixed micelles containing acceptor GalDAG (or GlcDAG) and 14C-labeled UDP-galactose or -glucose, respectively. After incubation, lipids were extracted and separated by thin layer chromatography, and products were visualized by autoradiography (lower panels) and quantified by a radioactivity imager. The enzyme activities of the variants are presented as percentage of control (WT) activity. Ala24 (yellow) in the atDGD2 active site (A) is the unique position mutated to Val in a selected thermosensitive A. thaliana (see “Results” and Ref. 18). Error bars, S.E.

In the case of atDGD2, the results show that with three of four mutations, the activity was drastically reduced as compared with the WT (V25A, less than 34%) or even totally abolished (K243A and D313A, not detected) (Fig. 2B). In the case of L229A, the mutation did not alter its activity dramatically. Most importantly, V25A (see Fig. 2B) maps just next to the conserved Ala24 position, which is mutated in a thermosensitive A. thaliana dgd1 mutant (18) (supplemental Fig. S1). It was suggested that in this mutant, lower GalGalDAG amounts (41% of WT) are due to a reduced atDGD1 activity, which we believe may be explained by an impaired UDP-Gal binding based on our modeling and activity results for this very conserved region in atDGD2 here.

An analogous approach was chosen for the bacterial homolog alDGS (Fig. 2, C and D). Candidate residues Glu244 and Ile246 were chosen because we believed that they may be part of a motif involved in substrate specificity (see below). Replacing these with alanine reduced alDGS activity drastically. Another alDGS candidate we selected, Gly245, also showed a strongly reduced activity for the respective mutant, G245A. This specific residue was of particular interest because it corresponds to a Gly/Pro “switch,” which we have observed for many of the GT-4 annotated glucosyl-/galactosyltransferases; many GT-4 sequences have a conserved (E/D)X7E motif in their C domain, involved in binding of the soluble nucleotide-sugar donor substrate (21). In most functionally annotated glucosyl enzymes in the GT-4 family database, we found Gly in position 4 of the motif, whereas the annotated galactosyl enzymes have Pro in this position (data not shown). Hence, we suspected that this location may potentially be involved in selecting for the orientation of the carbon 4 hydroxyl group differing between Glc and Gal. Furthermore, all eukaryotic DGDs in Fig. 1A are “galactosyltransferases,” with a Cys in this position (see the supplemental data), indicating an evolutionary adaptation for the DGD subgroup. We measured the activity of the respective atDGD2 C316A mutant and observed only a very minor reduction of 10%. This may be explained by the fact that the corresponding Cys in the atDGD2 motif is not in contact with UDP-Gal, according to our modeling (data not shown). Also, efforts to change the substrate specificity to UDP-Glc by replacing the Cys with a Gly or Pro proved unsuccessful because they both reduced activity to 15% yet without any increased preference for UDP-Glc as sugar donor (data not shown). Nevertheless, our attempts to identify critical substrate-interacting residues on the basis of this model were successful, thus giving relevance to the models.

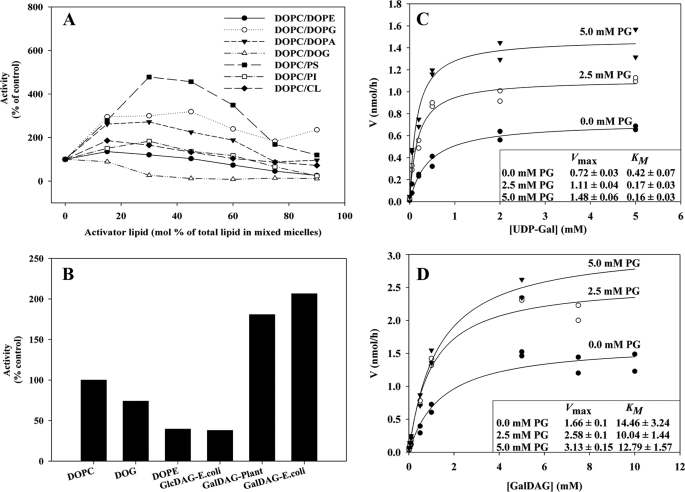

atDGD2-mediated Activity Is Modulated by Lipid Environment

Previous analyses for the corresponding A. laidlawii enzymes have shown that stimulatory effects of surrounding lipids can be important for setting the metabolic “balance” between GlcDAG and GlcGlcDAG. In vitro studies with the atDGD2 expressed in E. coli showed that GalGalDAG synthesis can be stimulated substantially by other lipids (Fig. 3A). In a mixed micelle system of fixed fractions of CHAPS (20 mm) and other lipids (10 mm), respectively, variation within the latter constant fraction keeps a large, bilayer-like organization of the aggregates (51) but with varying properties. Several potential “activator” lipids were tested, varying in charge and curvature properties. atDGD2 appears to be responsive toward anionic lipids, such as PS, PG, and PA. In contrast to both alMGS and alDGS, it was not stimulated by cardiolipin. Because PG and cardiolipin are structurally related, this may indicate PG-specific sites. Surprisingly, it was not stimulated by nonbilayer-prone lipids (i.e. DOPE, DOG, or GlcDAG), which all increase the spontaneous curvature (Fig. 3B). The fact that higher amounts of the nonbilayer-prone GalDAG increased activity is expected, due to its substrate function (Fig. 3B). Hence, types and amounts of anionic lipids present in the membranes may indeed play a potential role as selective “controllers” of atDGD2 activities in situ, affecting the synthesis rates. Headgroup chemical structure also matters (i.e. PS has three charges (one positive and two negative charges), whereas PG has only a single negative charge (cf. Fig. 3A). Likewise, atMGD1 and -2 GT enzymes analogously reconstituted in such bicelles also showed strong stimulation by anionic phospholipid additives (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Modulation of atDGD2 activity by surrounding lipids. A, in vitro GalGalDAG enzymatic synthesis varies depending on the type of lipid present. Enzyme activity was measured in mixed micelles by changing the lipid composition. DOPC is the matrix lipid that was exchanged stepwise with increasing “activator” lipid of different properties within a 10 mm total lipid concentration window; lipid substrate concentration was at 1 mm GalDAG, and CHAPS was at 20 mm. Activities are presented as percentage of control activity. B, analysis of several nonbilayer-prone matrix lipids (4 mm) with DOPC as standard. C and D, variation of the GalGalDAG synthase activity with the concentration of its two substrates, UDP-galactose and GalDAG, respectively. Activities of purified proteins were measured in mixed micelles with increasing DOPG concentrations. Insets show the calculated maximal rates (Vmax) and Michaelis-Menten constants (Km).

We also investigated the kinetic behavior of atDGD2 to understand in more detail when and how the enzyme may respond to or even be dependent on its lipid environment. Heterologously expressed atDGD2 was purified by nickel chromatography (Fig. 3C), and enzyme activity was measured in mixed micelles (see above), with increasing DOPG concentrations and varying concentrations of both substrates, the soluble UDP-Gal and acceptor lipid GalDAG (Fig. 3, C and D). For the soluble substrate UDP-Gal, increasing PG concentrations correlated with higher Vmax values and higher affinities (Km). Synthesis rates for the lipid substrate could also be increased with higher PG concentrations, yet they did not alter the affinity, indicating that PG does not alter the interaction of the enzyme with its lipid substrate but increases turnover. Most important, the largest changes in rates occurred at very low GalDAG concentrations (Fig. 3D). It is unlikely that the very large fractions of GalDAG in vivo in the chloroplast are involved in regulation of GalGalDAG synthesis, whereas local changes in anionic lipid concentration should have a substantial effect. However, in root cells during phosphate starvation, where GalDAG concentrations are much lower (52), the output efficiency of atDGD2 will also be affected by the acceptor GalDAG amounts in addition to the anionic species.

Interface Tryptophans Are Important for Enzyme Activity

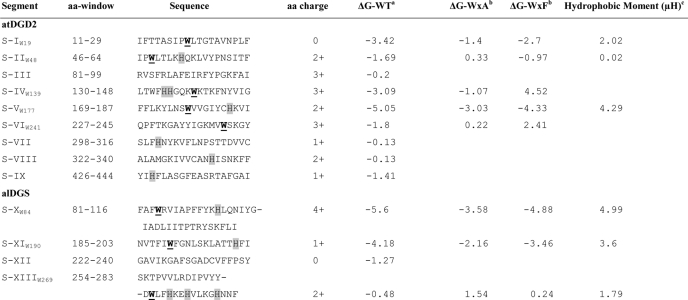

How do the DGDs interact with the bilayer interface? MPEx (available on the World Wide Web) calculates hydropathy plots for proteins based on experimentally obtained data for the partitioning of short peptides into PC vesicles. According to this algorithm, atC-DGD1, atDGD2, and alDGS enzymes all lack transmembrane segments but have a number of segments predicted to bind in the bilayer interface and thus qualify as monotopic membrane proteins. MPEx identified nine potential lipid-binding sequence segments in atDGD2 (Table 1) as well as four segments in alDGS, with ΔG values varying from 0 to −5 kcal/mol. It was noted that several of these segments contained tryptophan residues predominantly located in the N-terminal domain and, in the case of atDGD2, mostly as surface-oriented (see Fig. 4A). In total, the atDGD2 sequence contains eight Trp residues, of which six are present in these segments, and at least five of these appear surface-oriented in the three-dimensional structure. These tryptophans are not part of any conserved motifs in membrane proteins (data not shown), according to searches in the MeMotif database (53). The MPEx profile for atC-DGD1 was very similar to the profile of atDGD2, including the existence of all Trp residues, which are totally conserved (data not shown). This feature can vary among membrane-bound GTs; the strongly binding alMGS (54) has only one Trp in the full sequence, whereas high Trp numbers were found in the sequences of atMGD2 and atMGD3 and a lower number in atMGD1, soMGD1 (the spinach (Spinacia oleracea) homologue) (22), and MurG (55). Given that Trp has the strongest bilayer interface affinity of all amino acid residues (56), the numbers and localization of Trp residues in these monotopic proteins must clearly be important. Table 1 also reveals that the majority of the predicted segments in the two enzymes have a net positive charge. Likewise, most fragments have at least one His residue, which at lower pH potentially can become protonated, gaining a positive charge (cf. Ref. 57). A primary issue is whether all suggested segments (Fig. 4A) are in contact with the lipid bilayer simultaneously or if only a few of them are engaged, whereas the remaining ones could be involved in protein organization.

TABLE 1.

Prediction of bilayer interface association for atDGD2 and alDGS

Regions in atDGD2 and alDGS most likely to prefer association with a membrane interface according MPEx hydropathy analysis are identified. Interesting Trp residues are indicated in underlined boldface type. ΔG values of in silico Trp-to-Ala as well as Trp-to-Phe mutations are included on the right.

a For the most favorable 19-aa segment. The ΔG value was calculated by the Interface scale in MPEx (available on the World Wide Web), which measures free energy of transfer for an unfolded polypeptide chain from water to a phosphatidylcholine bilayer interface.

b ΔG values for segments with Ala and Phe point mutations.

c Hydrophobic moment according to Eisenberg et al. (92) calculated at the MPEx site. Gray shading indicates His residues.

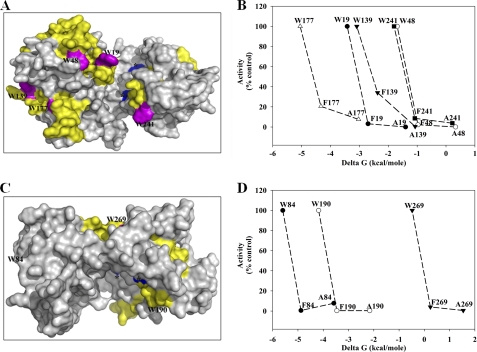

FIGURE 4.

Surface-oriented Trp residues are important for activity. A and C, surface maps of atDGD2 and alDGS structure models. Yellow patches highlight 19-aa-long segments in atDGD2 (A) and alDGS (C) as identified by MPEx to bind bilayer interfaces, due to their high predicted ΔG free energies of transfer values (cf. Table 1). Most of these segments harbor surface-oriented Trp residues, which are shown in purple. Blue, Asp/Glu and Glu in the conserved active site (E/D)X7E motifs common in the CAZy GT-4 family. B and D, selected Trp residues were mutated to Phe and Ala, and activities were measured and plotted against the respective predicted ΔG free energies of transfer values (cf. Table 1) to establish a potential correlation between the observed catalytic importance of the selected Trp residues and membrane association.

“In silico” mutations, in which all Trp residues were substituted to Ala lowered the ΔG values such that only six segments remained predicted as interface-associated for atDGD2 and three segments remained for alDGS (Table 1). This points toward the probable importance of the tryptophans in the bilayer association, namely conferring a critical threshold ΔG. To further investigate whether the extent of enzyme activity is linked to membrane association mediated by Trp, we replaced the Trp with the less strongly binding Phe. As expected, this resulted in somewhat intermediate results because Trp exhibits a higher free energy of transfer ΔG value (−1.85 kcal/mol) than Phe (−1.13 kcal/mol) or Ala (0.17 kcal/mol). These in silico results were then sustained by site-directed mutagenesis, all Trp residues found in the predicted segments of atDGD2 and alDGS were mutated to Ala and Phe, and GalGalDAG (and GlcGlcDAG, respectively) biosynthesis was assayed (Fig. 4B).

The enzymatic activity was strongly reduced or nearly abolished (<10%) in all Trp-to-Ala atDGD2 mutants, yet in some cases, Trp-to-Phe mutants partially retained activity. Similar results were obtained with alDGS: some residual activity still present in W84A (7%) but no activity detectable in the other two mutant proteins. In contrast to atDGD2, the corresponding Trp-to-Phe mutant proteins did not show a much stronger activity than the Trp-to-Ala versions of these mutated proteins. When correlating the experimentally obtained activities with the predicted values for membrane association, we observed a roughly linear relationship for at least one of the tested residues in atDGD2, namely Trp139 in segment SIV (Fig. 4C). In alDGS, two segments (harboring Trp84 and Trp269) of the four suggested are localized far from the active site region, whereas the Trp190 segment is adjacent and likely to have lipid contact. Taken together, these findings corroborate our hypothesis that some of the tryptophans in the predicted lipid-binding segments localized in the N-terminal domain are important for activity and can partially be substituted with Phe residues.

Binding of Trp-containing Segments to Lipid Bilayers

To evaluate the potential lipid binding properties of the various regions in more detail, both WT and the corresponding Trp-to-Ala mutants of the full-length atDGD2 as well as of the previously identified short segments were cloned as GFP fusions (Table 1). Assaying enzyme activity of the various DGD2-GFP full-length clones indicated that fusing DGD2 to GFP did not interfere with its activity and confirmed that the selected Trp residues (Table 1) are important for GalGalDAG synthase activity (data not shown).

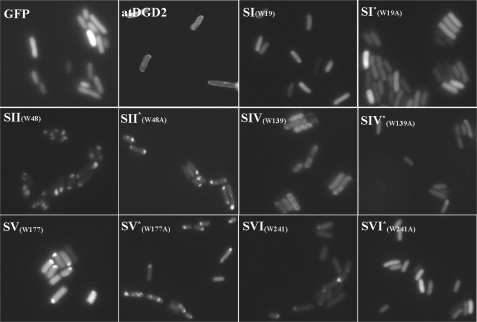

Subcellular localization of the various constructs in E. coli cells was traced by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5). Strong fluorescence was mainly found in the cytosol of cells expressing the soluble GFP alone. The signals of cells expressing the DGD2(WT)-GFP fusion protein were less strong; nevertheless, the fluorescence was mostly found at the membrane, confirming that the DGD2-GFP hybrid behaves as a membrane protein in E. coli. Analysis of cells expressing GFP fused to the short segments and their respective Trp-to-Ala mutant versions yielded fluorescence in all clones, yet the distribution pattern varied. Concerning the short segments described in Table 1, both for S-IW19 and mutant S-IW19A clones, fluorescence appeared more cytosolic. S-IIW48 locates preferentially to one of the two cell poles, and mutant S-IIW48A did not show any different pattern. S-IVW139 showed a clear membrane association, whereas mutant S-IVW139A fluorescence indicated a more cytosolic localization, thus strongly suggesting that this specific Trp plays a significant role in membrane binding. No difference was observed between S-VW177 and the corresponding mutant because both of them were seen as concentrated spots at one of the cell poles similar to S-IIW48. Finally, S-VIW241 also gave a strong fluorescent signal at the poles, whereas its respective mutant exhibited a more soluble pattern.

FIGURE 5.

Subcellular localization of the full-length atDGD2-GFP fusion protein and GFP-tagged atDGD2 19-aa segments. Shown is fluorescence microscopy of bacteria expressing either pure GFP, the entire atDGD2 protein fused to GFP, or different variants of several GFP-tagged 19-aa-long atDGD2 segments (cf. Table 1): both WT variants (SI–SVI) potentially involved in interfacial bilayer binding as predicted by MPEx analyses and the corresponding mutant segments (marked by asterisks), in which the catalytically important Trp residues were mutated to Ala.

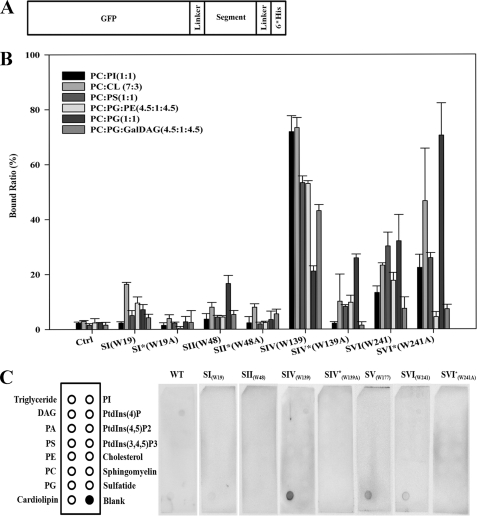

To measure membrane binding more quantitatively, we performed liposome binding assays, which allowed us to test different lipid classes (Fig. 6). The various GFP fusion proteins were purified by Ni2+-NTA chromatography and then incubated with liposomes of different lipid composition, which also carried a BODIPY-labeled lipid to enable monitoring amounts and stability of the liposomes. After incubation, free and liposome-bound peptides were separated by high speed centrifugation and quantified by measuring the GFP fluorescence subsequently, in addition to the BODIPY signal. Basically, both S-IW19 and S-IIW48 segments and the respective Trp-to-Ala mutants did not bind strongly to any of the tested liposomes. The former was found in the E. coli cytosol (see above; Fig. 5), whereas the latter was localized to the cell pole, which is enriched in the lipid CL. Hence, despite a smaller ΔG for S-IIW48 (Table 1), it may bind to the cell pole due to its positive charge and potentially pole curvature. S-IVW139 exhibited a strong binding to the liposomes (Fig. 6B), despite a ΔG value similar to that of the low binding S-IW19, and it was also clearly associated with the E. coli membrane (Fig. 5; see above), most likely because of the larger positive charge. Still, the S-IVW139A mutant keeps its charge but has a smaller ΔG (Table 1) and much lower binding (Fig. 5). These comparisons support the involvement of both hydrophobic and charge features in binding of the atDGD2 segments.

FIGURE 6.

Lipid binding assays for GFP-DGD2 fusion segments in vitro. A, scheme of GFP-DGD2 19-aa fusion segments. B, liposome binding assay for purified GFP-atDGD2 19-aa WT as well as mutated Trp-to-Ala segments. After purification, GFP-tagged segments were incubated with liposomes composed of different lipid compositions. Pure GFP protein was used as a control. Purified protein was incubated with liposomes, and free and liposome-bound peptides were separated by high speed centrifugation and quantified by measuring the GFP fluorescence subsequently. C, GFP-atDGD2 19-aa segments binding to Membrane Lipid StripsTM. The commercially available strip spotted with various lipids was incubated with selected and purified GFP-tagged atDGD2 segments, and binding was visualized by immunoprecipitation. Error bars, standard deviation.

Segment S-VIW241 and its Trp-to-Ala mutant had liposome binding in the intermediate range, and they also illustrated substantial differences for the various anionic lipids tested (Fig. 6B), including improvements for the Ala mutant over the wild type. Again, a small ΔG seemed to be compensated by a larger number of positive charges. The S-VW177 segment, possessing the largest ΔG (Table 1), clearly localized to the E. coli cell pole (above). However, it lysed all liposomes tested (thus preventing the centrifugation assay), although efficiency varied somewhat with peptide concentration and lipid type (data not shown). Notably, lysis was always somewhat lower for the Trp-to-Ala mutant, again illustrating the involvement of hydrophobicity. Because lysis demands binding, we conclude that segment S-VW177 has the strongest membrane affinity, in accordance with its large ΔG, which is potentially enhanced by the positive charges. It has been stated that helical amphiphilicity is much more important for interfacial binding than simple hydrophobicity (56). Interestingly, the highest values were obtained for both Trp139 and Trp177 segments (Table 1), which corroborates our findings above. Hence, segments IV and V qualify as the strongest bilayer-associated “anchor” segments of atDGD2.

In addition to the anionic phospholipids tested here (see above), cells contain a number of minor, highly charged phosphorylated variants of l-α-phosphatidylinositol, which are frequently involved in signaling and membrane traffic. None of the segments interacted with these l-α-phosphatidylinositol derivatives in a blot filter binding assay (see Fig. 6C). However, this lipid strip binding assay confirmed that segments IV and V and, to some extent, segment VI bound efficiently to the anionic CL and confirmed a strong reduction in binding in the S-IV Trp-to-Ala mutant (Fig. 6C). Here, the His residues, especially the pair in segment IV (Table 1), may also be involved because His and His pairs seem common in binding sites for CL in membrane proteins (58).

DISCUSSION

Evolutionary Considerations

The main function of atDGD2 lies in the DGD1-independent GalGalDAG biosynthesis to generate GalGalDAG during phosphate starvation, both in green tissue and in root cells. It has been suggested that this pathway takes place in the outer envelope of the plastid in collaboration with the type B MGD synthases supplying the GalDAG and that it may have evolved in seed plants to adapt to Pi-limited growth conditions. However, analogous mechanisms seem to occur also in bacteria. The phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 1A) demonstrated that in general, bacteria possess one variant, whereas most eukaryotes possess both DGD1 and DGD2 variants. A major characteristic feature for DGD1 proteins is the presence of an extra, large N-terminal domain (N-DGD1) in addition to the core GT-B part (C-DGD1). One may assume that DGD1 sequences have evolved as fusions of the catalytic GT domain to another independent activity during endosymbiosis. The sequence similarity for these extra N-terminal parts with other proteins is very low. A small number of (ancient) eukaryotes possess only one DGD1 homolog, but our search has revealed no example of a eukaryote so far that possesses exclusively only a DGD2 variant. This may indicate that N-DGD1 is an absolute requirement, whereas the presence of DGD2 may be dispensable. This is corroborated by in vivo studies because overexpression of atDGD2 could only compensate for the loss of GalGalDAG in the dgd1 mutant background when fused to N-DGD1 (59). The unidentified function of the N-DGD1 moiety must either be DGD1-specific, such as activating the C-terminal part of DGD1, or be involved in lipid transport and/or exchange between the chloroplast envelope membranes.

With respect to properties of the atC-DGD1 and atDGD2 GT enzymes, a number of traits are very similar and strongly indicate more or less identical activity profiles: a high aa sequence identity, with surface Trp residues essentially conserved, and very similar numbers and pairs of the charged Lys plus Arg (57/54), Asp plus Glu (58/56), His (15/14), and Cys residues (8/6), with most His and Cys conserved positionwise. The predicted hydropathy profiles and interface-binding segments (at MPEx) again are very similar, and identical GT-B structural templates were selected by the extensive MetaServer fold recognition survey. Hence, atC-DGD1 and atDGD2 most likely split by a gene duplication and diverged during evolution, forming a subgroup within the large GT-4 family in the CAZy GT systematics (i.e. having a Cys within the (E/D)X7E motif).

Lipid Bilayer Curvature Stress

A substantial intrinsic curvature must exist in the thylakoid membrane lipid bilayer due to the large fraction of the nonbilayer-prone GalDAG (52% in spinach chloroplasts), compared with the bilayer-forming GalGalDAG (26%) and PG plus sulfoquinovosyl-DAG (16%) (3, 60). Because the lateral distribution of the lipids seems to be heterogeneous, curvature will also vary along the plane. A high curvature is reflected in the formation of nonbilayer phases in total extracts and lipid mixtures close to biological conditions (12, 13). However, the atDGD1 and atDGD2 enzymes are localized in the outer envelope, where the fraction of GalDAG is only 17%, with GalGalDAG at 29% and PC at 32%. Hence, the curvature is bound to be lower here. Nevertheless, even if atDGD2 activity does not appear to be responsive toward curvature stress, this still may be the case for atDGD1. atDGD1 activity is up-regulated despite unchanged transcription levels during thermotolerance (18), leaving it unclear how the actual GalGalDAG/GalDAG ratio is sensed and transduced to achieve the correct balance under normal circumstances.

An inadequate curvature stress is the most reasonable explanation for the reduced thermotolerance in the previously described dgd1 mutant because enough lipid should be left for specific protein binding in various and numerous photosynthetic protein complex assemblies (61). By inactivation of the single Synechocystis DGD gene (cf. Fig. 1A), followed by limited exogenous GalGalDAG supply, it seems possible to separate curvature effects from site-specific effects in proteins (62). Also, increasing fractions of GalDAG have a substantial stimulatory influence on the activities of proteins in model systems, like two ATPases (63, 64), a dolichol GT (65), binding of preferredoxin (66), binding and insertion of leader peptidase (67), and de-epoxidation of pigments (68).

Sensing by atDGD2

Transcriptional regulation plays a major role, as shown during different stress conditions (15, 30). However, the local lipid environment around these interface-anchored proteins should potentially exert a substantial influence or controlling function because in vivo overexpression of the plant DGD synthases does not result in an increased GalGalDAG level (59). This implies that protein amount is not the limiting factor here. Similar features are also observed for several E. coli lipid enzymes. Likewise, for the archetypal monotopic membrane protein prostaglandin synthase, the local lipid environment has a substantial influence on enzyme activity (69).

It was very evident from the activities of atDGD2 in reconstituted bilayer-like micelles that the three different nonbilayer-prone lipids (DOG, DOPE, and GlcDAG) all decreased activity (Fig. 3B). This strongly indicates that increasing curvature stress by these additives has a retarding effect on product formation. Because these lipids have substantial differences in headgroup chemical structures, their common curvature-increasing features are the likely cause for the observed effects (Fig. 3B). In terms of the in vivo regulation of atDGD2, a stimulation of atDGD2 by negatively charged lipids may seem enigmatic at first sight, yet it could indeed be of relevance because phospholipids are present at the site of GalGalDAG synthesis and could therefore be involved in setting the phospholipid/GalGalDAG amount by linking the lipid status of the surrounding membranes to the activity of atDGD2. As outlined earlier, phosphate deprivation induces strong transcription, which presumably leads to enhanced translation of DGD2 protein. In this early stage, demand is high for a strong atDGD2 activity, which is achieved by the still high amounts of (anionic) phospholipids. As a result, large amounts of GalGalDAG are synthesized, which lowers the local concentration of all phospholipids and, concomitantly, atDGD2 activity. However, the exact fluctuations in the lipid composition of the outer chloroplast envelope during phosphate stress remain unknown so far due to technical constraints. (Phospho)lipid levels have been shown to change in response to phosphate deprivation, with differences observed between roots and leaves. PG (which is only present in chloroplasts) levels decrease in rosettes and roots, whereas total PA levels decrease in roots but remain unchanged in rosettes. PA in particular is an interesting candidate because it is an established signaling molecule in plants and an intermediate in the supply of eukaryotic substrate for GalGalDAG biosynthesis in roots during phosphate deprivation by the PC-hydrolyzing PLD-ζ 2 activity (8, 70). In addition, PA has been shown to bind to the TGD (trigalactosyldiacylglycerol) transport complex, which is involved in the lipid import into chloroplasts for galactolipid biosynthesis (71), as well as to stimulate GalDAG biosynthesis (72, 73).

The MGD enzymes synthesizing the lipid substrate GalDAG in the preceding pathway are of a similar GT-B fold (22) but are grouped in another CAZy family (GT-28). Several sequences features are conserved between the three isoenzymes, including a number of Trp residues on the potential interface-binding surfaces (72). Analyzing cloned atMGD1 and -2 in analogous mixed micelle systems, as done for atDGD2 (above), revealed that these enzymes did not respond to nonbilayer-prone additives, similar to atDGD2. However, they were substantially stimulated by anionic phospholipids, especially by PA, which was even more potent than as observed in the atDGD2 assays here (see Fig. 3A).

Hence, the synthesis of the two major GalDAG and GalGalDAG lipids in the outer chloroplast envelope membrane seems to be locally governed by lipid bilayer anionic charge. Still, these two enzymes can set (or modify) a certain bilayer curvature stress by their relative rates of synthesis, the latter of which can be strongly modulated by anionic lipids (e.g. see Fig. 3C). This is analogous to E. coli, where the synthesis of the major, nonbilayer-prone lipid PE is governed by the anionic bilayer surface charge density (i.e. mol %) (74) but not by curvature itself. Two key enzymes, the phosphatidylserine synthase and cardiolipin synthase (75), are both monotopic, similar to a phospholipase D structure, and have critical Trp residues (according to our MetaServer, TMHMM, and MPEx predictions (data not shown)). Likewise, the consecutive GalDAG and GalGalDAG synthases in Synechocystis seem to be controlled by the anionic charged lipid fraction, as indicated from DGD (monotopic) inactivation data (76).

Unique Roles for Tryptophan Residues

The enrichment of the amphipathic Trp in the bilayer interface regions is well established for many transmembrane proteins (77). In an analogous manner, they are enriched in re-entrant regions of these proteins (78) and in the surface of many soluble, membrane-interacting proteins (79). However, in a multivariate sequence discrimination of many membrane-associated lipid GTs from soluble GTs of the same GT-B fold type, Trp was not a decisive factor but was only enriched in some of the membrane enzymes (24). Hence, Trp should bring specific features for these latter proteins, including atDGD2. To the best of our knowledge, it is rare that all five selected Trp-to-Ala mutations have strong functional consequences, as for atDGD2 here (Fig. 4B). Three potential functions may be suggested for the surface-exposed Trp residues in atDGD2 (Table 1 and Fig. 4) and the homologous ones in atC-DGD1. (i) The aromatic, amphipathic, and hydrogen-bonding characteristics of Trp in the various surface-exposed sequence segments are important for the internal structure and functions of the peptide segments, or (ii) Trp are oriented out toward the membrane and interact with the lipid bilayer interface. (iii) Finally, one or more of the Trp residues are part of the binding region for the acceptor substrate GalDAG or donor UDP-Glc, respectively, because Trp is strongly overrepresented in the interacting surfaces of many sugar-binding proteins (80). Supporting this, a Trp-to-Ala mutation in the potential bilayer-interacting surface of the preceding atMGD1 enzyme yielded a severe reduction in activity (73). This selected Trp is one of several Trp residues at the bilayer interface of atMGD1 contributing similar critical hydrophobicity as for the Trp segments of atDGD2 (data not shown).

The localization of the five analyzed Trp segments in well separated regions of the “bottom” surface in atDGD2 (Figs. 1 and 4) is an indication for differentiated functions. The binding here of the selected segments did not show a simple correlation with the calculated ΔG values (Table 1); rather, the cationic charge, hydrophobic moment, and potentially His residues seem to have a substantial influence. However, all segments except S-VIW241 had decreased binding for the Trp-to-Ala mutants, especially segment S-IVW139. An analogous binding assay for a PA-binding domain was also sensitive to aa point changes (81). According to the liposome binding assay here, (wild-type) segments S-IVW139 and S-VW177 with their strong binding should qualify as “anchor points.” Replacing their Trp with Phe still yielded substantial activity of the enzyme (Fig. 4B), whereas the corresponding changes for segments I, II, and VI essentially abolished activity, although the interfacial affinity of Phe is not that different from Trp (cf. Table 1). This may indicate that these three Trp residues have more specific functions than mere passive bilayer anchoring. All three are facing the active site cleft between the N and C domains. Its vicinity to downstream residues interacting with the donor substrate UDP-Gal may hint at a role for guiding/binding the incoming acceptor substrate lipid GalDAG. Note that the surface Trp190 and Trp269 residues in alDGS both seem integrated deeper into the protein structure and potentially less in contact with the bilayer or substrates (Fig. 4C), whereas Trp84 is close to the UDP-Glc site (Fig. 2C). For alDGS, the Trp-to-Phe and Ala mutations also essentially abolished activity (Fig. 4, C and D).

Hence, several of the atDGD2 Trp residues seem to be involved in lipid interactions. In the soluble cobra phospholipase A2, several Trp residues yield affinity for (zwitterionic) PC liposomes (82), and for human PLA2, affinity for PC bilayers can be increased by stepwise replacement of hydrophobic aa in the binding surface with Trp, which also seemed to modify the interface orientation of the enzyme (83). The affinity of Trp for PC is supported by NMR analyses (84), but molecular dynamics indicate that more space around the zwitterionic PE headgroup is even more beneficial (85). In the anchoring segments of the monotopic prostaglandin synthase (COX-2), mutating Trp85 to Cys caused the largest decrease in activity of 25 different positions tested (86). As for atDGD2, mutating three different Trp residues did not release the protein from the membrane (87). Single Trp residues are also very important for bilayer binding of a protein kinase C C1 domain (88) and eukaryotic glycolipid transfer proteins (89).

Regulation at the Membrane Interface

To see if membrane association within monotopic GTs has common molecular features, atDGD2, atMGD1, and PimA from family GT4, atMGD1 and MurG from family GT28, and GumK from family GT70 were selected. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, it is evident that most of the MPEx-predicted segments (yellow patches in supplemental Fig. S2) and many of the Trp residues are localized on the N domains of most GTs, indicating that these are involved in membrane binding. The hydrophobic segments are mostly surrounded by positively charged clusters (blue patches). In addition, the N-terminal domains have higher pI values than the C-terminal domains, reflecting the presence of positively charged surfaces (supplemental Fig. S2).

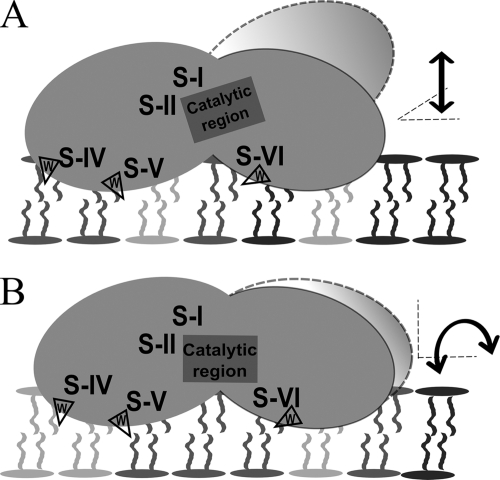

From these common features, the findings here for the Trp segments and the anionic lipid-stimulated activity of atDGD2 can be translated into a potential regulatory model of the enzyme at the membrane bilayer interface (see Fig. 7). In this, segments IV and V are permanent anchor points for the N domain in the interface. Positive charges on the bottom surface and segment VI are brought down to the interface more frequently, due to electrostatic attraction, by higher anionic lipid fractions, positioning the catalytic region (including segment I) down into the interface, harboring the acceptor lipid substrate GalDAG. The Gal headgroup of the latter is fairly small and has to reach into the active site cleft. This may be achieved by an up-down movement (“dipping”) of the C domain or by a sideways rolling of the entire enzyme, also assuring access for the soluble UDP-Gal donor substrate (see Fig. 7). Such a lipid charge-dependent mechanism would also eventually be self-inhibiting because phospholipid amounts decrease during phosphate stress due to degradation, which is followed by replacement with GalGalDAG, thus establishing the new GalGalDAG levels by the decreasing phospholipid amounts.

FIGURE 7.

Model for interface regulation of atDGD2 activity. According to modeling, binding, and activity data here, atDGD2 is associated with the membrane bilayer interface. Trp-containing segments IV and V in the N domain (cf. Fig. 4A and Table 1) are permanent anchor points for the enzyme in the bilayer. Enzyme activity (i.e. synthesis of GalGalDAG) is stimulated by anionic lipids (Fig. 3, A and C) attracting the positively charged interaction surface of atDGD2 (see Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S2) and the catalytic region down into the interface, where the acceptor (lipid) acceptor substrate GalDAG is localized. Trp segments I, II, and VI are in close vicinity to the catalytic region and may be involved in substrate guiding or binding. Two modes of reorientation of the enzyme upon stimulation by anionic lipids are possible: an up-down displacement (“dipping”) of the C domain (to the right) (A) and a “rolling” transfer of the catalytic region into the interface (B). Each of these must also provide access for the soluble UDP-Gal donor substrate.

Conclusions

Chloroplast membranes have a substantial bilayer curvature stress due to high fractions of the nonbilayer-prone GalDAG lipid versus the consecutive GalGalDAG and other bilayer-forming lipids. However, the increased synthesis of GalGalDAG by the atDGD2 GT enzyme, as a response to phosphate starvation and several other stress conditions, seems to be regulated at the protein (post-translational) activity level by local bilayer charge conditions given by especially anionic phospholipids but not by curvature. This principle is similar for E. coli membrane polar lipid synthesis. atDGD2 and atC-DGD1 have conserved double Rossmann fold (GT-B) structures, similar to many bacterial lipid GTs, monotopically anchored in the bilayer interface. atDGD2 has several bilayer interface segments, most of which have Trp residues critical for enzyme activity. Binding and mutation data indicate that these Trp segments constitute bilayer anchor regions for the enzyme as well as substrate-interacting ones. In atDGD2 (and atC-DGD1), these regions are separated by a multitude of positive charges, likely to interact with stimulatory anionic phospholipids and potentially also promoting bilayer (or interface) penetration (25). Together, this may constitute the mechanism for control, where the amount of anionic phospholipids will determine the frequency of contacts between the catalytic region in atDGD2 and the acceptor lipid substrate GalDAG in the membrane interface. An analogous regulatory mechanism seems to operate through the glycosyltransferase YpfP (90) in the bacterium B. subtilis, which responds to phosphate (91) and lipid conditions (28).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The contributions of the students Arezki Sedoud, Antonia Richter, Beata Winiarska, and Richard Hedman are especially acknowledged. We also thank Prof. Lars Wieslander for fluorescence microscopy access. We are very grateful to Dr. Dan Daley for proofreading the English.

This work was supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, European Commission FP6 Marie-Curie Action BIOCONTROL, and the Swedish Research Council.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- GalDAG

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (1,2-diacyl-3-O-(β-d-galactopyranosyl)-sn-glycerol)

- GalGalDAG

- digalactosyldiacylglycerol (1,2-diacyl-3-O-[α-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-β-d-galactopyranosyl]-sn-glycerol)

- GlcDAG

- monoglucosyldiacylglycerol (1,2-diacyl-3-O-(α-d-glucopyranosyl)-sn-glycerol)

- GlcGlcDAG

- diglucosyldiacylglycerol (1,2-diacyl-3-O-[α-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-O-α-d-glucopyranosyl]-sn-glycerol)

- GT

- glycosyltransferase

- MGD

- monoglycosyldiacylglycerol synthase

- DGD

- diglycosyldiacylglycerol synthase

- atDGD1 and atDGD2

- digalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase 1 and 2, respectively, from A. thaliana

- alMGS and alDGS

- mono- and diglucosyldiacylglycerol synthase, respectively, from A. laidlawii

- atMGD1, atMGD2, and atMGD3

- monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase 1, 2, and 3, respectively, from A. thaliana

- MurG

- N-acetylmuramyl-(pentapeptide) pyrophosphorylundecaprenol N-acetylglucosamine transferase from E. coli K12

- GumK

- (xanthan) α-Man-(1,3)-β-Glc-(1,4)-α-Glc-PP-polyisoprenyl β-1,2-glucuronosyltransferase from Xanthomonas campestris

- PimA

- phosphatidylinositol mannosyltransferase from Mycobacterium smegmatis

- PG

- phosphatidylglycerol

- DOPG

- dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol

- DOPC

- dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOG

- rac-1,2-dioleoylglycerol

- DOPE

- dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- CL

- cardiolipin

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- aa

- amino acid(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Granseth E., Daley D. O., Rapp M., Melén K., von Heijne G. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 352, 489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Booth P. J., Curnow P. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 8–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marsh D. (2007) Biophys. J. 93, 3884–3899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelly A. A., Dörmann P. (2004) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7, 262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edman M., Berg S., Storm P., Wikström M., Vikström S., Ohman A., Wieslander A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8420–8428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vikström S., Li L., Karlsson O. P., Wieslander A. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 5511–5520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alley S. H., Ces O., Templer R. H., Barahona M. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 2938–2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cruz-Ramírez A., Oropeza-Aburto A., Razo-Hernández F., Ramírez-Chávez E., Herrera-Estrella L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6765–6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaude N., Tippmann H., Flemetakis E., Katinakis P., Udvardi M., Dörmann P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34624–34630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McMahon H. T., Gallop J. L. (2005) Nature 438, 590–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zimmerberg J., Kozlov M. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams W. P., Quinn P. J. (1987) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 19, 605–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Webb M. S., Green B. R. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1060, 133–158 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mock T., Kroon B. M. (2002) Phytochemistry 61, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaude N., Bréhélin C., Tischendorf G., Kessler F., Dörmann P. (2007) Plant J. 49, 729–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Torres-Franklin M. L., Gigon A., de Melo D. F., Zuily-Fodil Y., Pham-Thi A. T. (2007) Physiol. Plant. 131, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Süss K. H., Yordanov I. T. (1986) Plant Physiol. 81, 192–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen J., Burke J. J., Xin Z., Xu C., Velten J. (2006) Plant Cell Environ. 29, 1437–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moellering E. R., Muthan B., Benning C. (2010) Science 330, 226–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barkan L., Vijayan P., Carlsson A. S., Mekhedov S., Browse J. (2006) Plant Physiol. 141, 1012–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Botté C., Jeanneau C., Snajdrova L., Bastien O., Imberty A., Breton C., Maréchal E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34691–34701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hölzl G., Leipelt M., Ott C., Zähringer U., Lindner B., Warnecke D., Heinz E. (2005) Glycobiology 15, 874–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lind J., Rämö T., Klement M. L., Bárány-Wallje E., Epand R. M., Epand R. F., Mäler L., Wieslander A. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 5664–5677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balali-Mood K., Bond P. J., Sansom M. S. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 2135–2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guerin M. E., Kordulakova J., Schaeffer F., Svetlikova Z., Buschiazzo A., Giganti D., Gicquel B., Mikusova K., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20705–20714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klement M. L., Ojemyr L., Tagscherer K. E., Widmalm G., Wieslander A. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1444–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsumoto K., Okada M., Horikoshi Y., Matsuzaki H., Kishi T., Itaya M., Shibuya I. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 100–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wikström M., Kelly A. A., Georgiev A., Eriksson H. M., Klement M. R., Bogdanov M., Dowhan W., Wieslander A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 954–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly A. A., Dörmann P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Georgiev A. (2008) Membrane Stress and the Role of GYF Domain Proteins. Ph.D. thesis, Stockholm University [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karlsson O. P., Dahlqvist A., Vikström S., Wieslander A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Buser C. A., McLaughlin S. (1998) Methods Mol. Biol. 84, 267–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guerin M. E., Buschiazzo A., Korduláková J., Jackson M., Alzari P. M. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61, 518–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barreras M., Salinas S. R., Abdian P. L., Kampel M. A., Ielpi L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25027–25035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu Y., Chen L., Ha S., Gross B., Falcone B., Walker D., Mokhtarzadeh M., Walker S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 845–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ginalski K., Elofsson A., Fischer D., Rychlewski L. (2003) Bioinformatics 19, 1015–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]