Abstract

Keratinocytes play a critical role in maintaining epidermal barrier function. Activated protein C (APC), a natural anticoagulant with anti-inflammatory and endothelial barrier protective properties, significantly increased the barrier impedance of keratinocyte monolayers, measured by electric cell substrate impedance sensing and FITC-dextran flux. In response to APC, Tie2, a tyrosine kinase receptor, was rapidly activated within 30 min, and relocated to cell-cell contacts. APC also increased junction proteins zona occludens, claudin-1 and VE-cadherin. Inhibition of Tie2 by its peptide inhibitor or small interfering RNA abolished the barrier protective effect of APC. Interestingly, APC did not activate Tie2 through its major ligand, angiopoietin-1, but instead acted by binding to endothelial protein C receptor, cleaving protease-activated receptor-1 and transactivating EGF receptor. Furthermore, when activation of Akt, but not ERK, was inhibited, the barrier protective effect of APC on keratinocytes was abolished. Thus, APC activates Tie2, via a mechanism requiring, in sequential order, the receptors, endothelial protein C receptor, protease-activated receptor-1, and EGF receptor, which selectively enhances the PI3K/Akt signaling to enhance junctional complexes and reduce keratinocyte permeability.

Keywords: Cell Permeabilization, Epithelial Cell, ERK, Skin, Tight Junction, Barrier Integrity, Keratinocyte, Tie2, Activated Protein C, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

Introduction

The skin forms an effective barrier between the human body and the outside environment and protects the body from dehydration and environmental insults (1). Disruption of this barrier function is responsible for many skin disorders, such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis (2, 3). The barrier properties of epithelia are largely dependent on the function and integrity of the tight junctions between keratinocytes (occludins, claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules) (4), which seal the intercellular space between neighboring cells and control the pathway of molecules (5). Deregulation of these junction proteins perturbs this barrier (1). For example, deficiency of claudin-1 results in epidermal water loss and, ultimately, the neonatal death of mice (6).

Tie2 is a protein-tyrosine kinase receptor expressed by endothelial and epithelial cells. The major ligands for Tie2 are angiopoietin (Ang)2 1 and Ang2, which bind with similar affinity (7, 8). Although Ang1 is an agonist, Ang2 is generally considered as an antagonist but may act as an agonist depending on the cell type and microenvironment (8). The binding of Ang1 to Tie2 results in rapid receptor autophosphorylation, which in turn mediates endothelial cell survival, cell migration, angiogenesis, and barrier function (8–10). Recent studies show that Tie2 acts not only as a receptor for the Angs but also as a junction protein to maintain the vascular integrity of mature vessels by enhancing endothelial barrier function and inhibiting apoptosis of endothelial cells (8–11).

Activated protein C (APC) is derived from its precursor protein C and functions as a physiological anticoagulant with cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties (12, 13). APC stimulates cell growth and migration of cultured human skin keratinocytes (14) and protects keratinocytes from apoptosis. These cytoprotective properties of APC are mediated through endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR), protease activated receptor (PAR)-1, or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (15, 16). Recent studies show that APC enhances the integrity of blood vessels through PAR-1 to stabilize the cytoskeleton and reduce endothelial permeability partly via activation of the endothelial receptor, Tie2 (17–20). Here, using human skin keratinocytes, we elucidated the signaling pathway to explain how APC exerts a protective effect on the skin barrier.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Keratinocyte Culture and Reagents

Normal keratinocytes were isolated from neonatal foreskins as described previously (14). Adult skin keratinocytes were kindly provided by Dr. Zhe Li (Skin Laboratory, Concord Hospital, Sydney, Australia). Extracted cells were cultured in keratinocyte-serum free medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. The Ca2+ concentration in medium used in this study was 0.09 mm. When greater than 70% confluent, the cells were trypsinized and seeded into either 24-well culture plates or 8-well PermanoxTM slides (Nalge Nunc International Corp.) and then cultured to confluency. The keratinocyte monolayers were incubated in keratinocyte-serum free medium with the same Ca2+ concentration (0.09 mm, the keratinocyte-serum free medium contained) but without bovine pituitary extract and EGF (basal medium) for 72 h, then switched to fresh basal medium, and treated with recombinant APC (Xigris; Eli Lilly), EPCR blocking antibody RCR252, EPCR nonblocking antibody RCR92 (gift from Professor Fukudome, Department of Immunology, Saga Medical School, Nabeshima, Saga, Japan), PD153035, an inhibitor of EGFR, Tie2 kinase inhibitor (2.0 μm), inhibitors of ERK (5 μm), and Akt (1 μm) (EMD Biosciences). Inhibitors and blocking antibodies did not exert any cytotoxic effect on keratinocytes when used at the indicated concentrations (data not shown). The cells and culture supernatants were collected for further analysis. The use of human tissues was in accordance with the approval of the North Sydney Central Coast Area Health human ethics committee.

siRNA Preparation and Nucleofection

Validated PAR-1 and Tie2 siRNA and scrambled control siRNA duplex oligonucleotides were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Keratinocytes were adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/ml in growth medium and subjected to nucleofection using the human keratinocyte NucleofectorTM kit and the Amaxa NucleofectorTM II machine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa Biosystems). The cells were allowed to attach overnight and then trypsinized and seeded into either 24-well plates (4 × 105 cells/ml) or 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) and incubated for 48 and 72 h.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from keratinocytes using Tri reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)15 as a primer (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The levels of mRNA were semi-quantified using real time PCR on a Rotor-gene 3000A (Corbett Research,). The samples were normalized to the housekeeping gene RPL13A, and the results were reported for each sample relative to the control. Primers used were as follows: Tie2: sense, 5′-GGTTCCTTCATCCATTCAGTGCC, and antisense, 5′-CAGTTCACAAGCCTTCTCACACG; PAR-1: sense, 5′-TGTGAACTGATCATGTTTATG, and antisense, 5′-TTCGTAAGATAAGAGATATGT; and RPL13A: sense, 5′-AAGCCTACAAGAAAGTTTGCCTATC, and antisense, 5′-TGTTTCCGTAGCCTCATGAGC.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide Assay

The colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay was performed to quantitate the effect of different test agents on cell growth and viability as described previously (16).

Western Blot

Keratinocytes were lysed with lysis buffer (0.15 m NaCl, 0.01 mm PMSF, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.02 m Tris, 6 m urea/H2O) supplemented with protease inhibitor and phosphate inhibitor (Roche Applied Science). The cell membrane proteins were extracted using a Qproteome plasma membrane protein kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The primary antibodies used were: VE-cadherin, ZO-1 (R & D systems), claudin-1, occludin, junctional adhesion molecule A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Tie2 and phosphorylated (P)-Tie2, EGFR and P-EGFR (R & D Systems), Akt, P-Akt, ERK, and P-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoreactivity was detected using the ECL detection system (Amersham Biosciences). Anti-human β-actin antibody was included to normalize against unequal loading.

Immunostaining

Cultured keratinocytes in Permanox slides were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Human foreskin and adult skin were fixed with 10% PBS-buffered formalin. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and subjected to immunostaining using rabbit anti-human Tie2 P-Tie2, Akt P-Akt, ERK, and P-ERK antibodies and stained by a DAKO LSAB+Systems stain kit (DAKO Corporation). Rabbit IgG at the same concentration with individual antibody was used as the negative control.

For immunofluorescent staining, fixed cells were blocked by 5% horse serum in PBS, incubated with primary antibodies for 2 days at 4 °C and then with second antibodies conjugated with Cy3 (red) or FITC (green) (1:400, Sigma), and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE 80i). The images were processed using image analysis (Diagnostic Instruments, Australia and Image J).

Apoptosis Detection

Apoptotic keratinocytes were detected using an in situ cell death detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). Briefly, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in the presence of fluorescein-labeled dUTP. TUNEL-positive cells were visualized using an anti-fluorescein peroxidase-conjugated antibody. The cells were counterstained with DAPI. The frequency of apoptotic cells was determined by counting TUNEL-positive cells and the total cell number under a high magnification view (40×).

Assessment of Barrier Function and Cell Migration by Electric Cell Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS)

The changes in transepithelial electrical resistance were monitored in real time using an ECIS model 1600R instrument (Applied BioPhysics) with 8W10E+ ECIS arrays and results expressed as impedance. Briefly, the cells are grown on the surface of small and planar gold film electrodes, which are deposited on the bottom of each well. The sensing area within a single well of the 8W10E+ ECIS arrays consists of 10 active working electrodes in parallel that are distributed over the bottom of the well and a counter electrode with a considerably larger surface area. A noninvasive alternating current (<1 μA) is applied to the electrodes, which are electrically connected via the electrolytes of the cell culture medium above the cells. The ECIS device reads the associated voltage drop across the system (in-phase with the current) and determines the electrical resistance of the cell-covered electrodes. In this study, keratinocytes were grown on 8W10E+ ECIS arrays (an 8-well chamber slide device) until stable resistances of ≥1500 Ω at 15 kHz were reached. To prevent proliferation, the cells were pretreated with mitomycin C (10 μg/ml, Sigma), which was applied to the cells 2 h before treatment. After switching to fresh medium, the cells were balanced in the ECIS equipment until a stable impedance was reached. The controls used during experiments were: heat-inactivated APC (for APC treatment), nonblocking antibody RCR92 (for EPCR blocking antibody), or medium containing the same low amount of dimethyl sulfoxide used for solubilizing the inhibitors (for PAR1, Tie2, EGFR, ERK, and Akt inhibitors). After adding test agents, the average impedance over 24 h was measured. The effect of treatment of stable keratinocyte monolayers was analyzed by comparing the average normalized impedance before treatment with that after treatment.

Measurement of Flux of FITC-Dextran

The cells were cultured until confluence on culture inserts (0.4-μm pore size) and then treated for 24 h. The flux was measured as described previously (21). In brief, culture medium was replaced with P buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 10 mm glucose, 3 mm CaCl2, 145 mm NaCl), and 1 mg/ml FITC-dextran (4 kDa: Sigma) was added to the upper wells. At 0, 30, 60, and 120 min after the addition of FITC-dextran into the outer chambers, the media from the lower wells were collected, and the flux of FITC-dextran in the media was measured at wavelengths of excitation 485 and emission 520 nm. The flux of FITC-dextran represents the permeability of the keratinocyte monolayer.

Statistical Analysis

Significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance and Student-Newman-Keul's test. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

APC Enhancement of Keratinocyte Barrier Integrity Is Mediated by Tie2

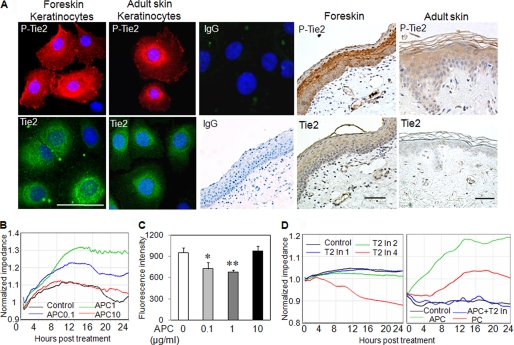

We have previously shown that APC acts via Tie2 to enhance endothelial barrier function (20). Tie2 is recognized as an endothelial receptor, so initially we examined whether Tie2 or P-Tie2 was expressed in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Using immunofluorescent staining, Tie2 and P-Tie2 were distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of keratinocytes in both neonatal foreskin keratinocytes and adult skin keratinocytes. However, adult skin keratinocytes showed less intensive staining for Tie-2 and P-Tie2 when compared with neonatal foreskin keratinocytes (Fig. 1A). Foreskin epidermis showed faint staining of Tie2 but strong staining for P-Tie2, which was mainly located in the uppermost layers of the epidermis (Fig. 1A). Similarly, P-Tie2 was expressed by normal adult skin epidermis, although the staining intensity was considerably lower than foreskin (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Tie2 is expressed by keratinocytes and mediates the protective effect of APC on barrier function. A, Tie2 and P-Tie2 expression by cultured human neonatal foreskin and adult skin keratinocytes, foreskin epidermis, and adult skin epidermis as detected by immunofluorescent (blue staining (DAPI), nucleus; red staining, P-Tie2; green staining, Tie2) and immunohistochemical staining. Rabbit IgG staining served as the negative control for keratinocytes (top row) and foreskin epidermis (bottom row). Scale bar, 50 μm. The pictures are representative of at least three different samples. B, the normalized impedance of keratinocyte monolayers treated with APC (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) over a period of 24 h. C, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with APC (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) for 24 h, and then FITC-dextran was added to upper wells of inserts, and the flux of FITC-dextran in the media from lower wells was measured by fluorescence as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are expressed as the means ± S.D. (n = 3). D, the normalized impedance of keratinocyte monolayers treated with Tie2 inhibitor (T2 In 1, T2 In 2, and T2 In 4 representing 1, 2, and 4 μm, respectively), PC (1 μg/ml), APC (1 μg/ml), or APC plus Tie2 inhibitor (T2 In, 2 μm) over a period of 24 h. The average normalized impedance of cell monolayers over 24 h was compared. The graph is representative of three experiments.

Next, the impedance of cell monolayers treated with APC (0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml) was monitored in real time by ECIS to determine whether APC can enhance epidermal barrier function. APC dose-dependently increased the impedance at 24 h (Fig. 1B), peaking at 1 μg/ml. Interestingly, APC had no effect when used at 10 μg/ml. PC, the inactive precursor of APC, displayed only a partial protective effect on the keratinocyte barrier when used at 1 μg/ml (Fig. 1D). To validate the impedance data detected by ECIS, we measured the flux of FITC-dextran permeating from the apical to the basal side of keratinocyte monolayers following APC treatment for 24 h. There was a significant decrease in the paracellular permeability of keratinocyte monolayers incubated with APC at 0.1 and 1 μg/ml (Fig. 1C), but not at 10 μg/ml, confirming the ECIS results.

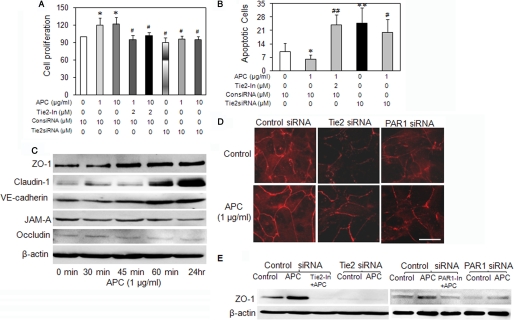

To determine whether Tie2 contributes to keratinocyte barrier function, cell monolayers were treated with Tie2 kinase inhibitor (1, 2, and 4 μm), and the impedance was measured by ECIS. Tie2 inhibitor at 4, but not at 1 and 2 μm, markedly reduced the basal impedance (Fig. 1D). However, at 4 μm, Tie2 inhibitor also induced cell detachment (data not shown); hence the 2 μm was selected for further experiments. Pretreatment of cell monolayers with 2 μm Tie2 inhibitor totally eliminated the effect of APC on monolayer impedance (Fig. 1D). To further establish whether APC functions through Tie2, keratinocytes were transfected with Tie2 siRNA or treated with a Tie2 inhibitor. Tie2 siRNA was more than 80% efficacious in suppressing gene expression 48 h post-transfection, as detected by real time RT-PCR (supplemental Fig. S1A). Suppressing Tie2 either by its siRNA or synthetic inhibitor suppressed both control and APC-stimulated keratinocyte proliferation at 72 h (Fig. 2A). In addition, inhibition of Tie2 increased the level of both control and APC-treated cell apoptosis (Fig. 2B), as detected by TUNNEL assay, which measures the DNA strand breaks that occur in the specialized form of keratinocyte apoptosis (22). These results show that Tie2 mediates the barrier protective, proliferative, and anti-apoptotic effects of APC on keratinocytes. Interestingly, Tie2 is also involved in these responses in the absence of exogenous APC, suggesting an important role for endogenous Tie2 activation in protecting keratinocytes.

FIGURE 2.

APC enhances cell proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and stimulates junctional proteins via Tie2. A, keratinocytes were transfected with siRNA for 24 h, and then cells were trypsinized and equal numbers were seeded into 96-well plates. The cells were allowed to attach for another 24 h. APC and Tie2 inhibitor (Tie2-In) were added at 48 h post-siRNA transfection. Cell proliferation was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay at 72 h post-transfection and is expressed as a percentage of control (means ± S.D., n = 3). B, siRNA-transfected keratinocytes were seeded onto slides and were treated with APC and Tie2 inhibitor (Tie2-In) at 48 h post-transfection for a further 24 h. Apoptotic cells were detected by in situ cell death kit (TUNEL assay) and are expressed as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with control; #, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01, compared with APC (1 μg/ml). C, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with APC for indicated time and junctional proteins were detected by Western blotting. JAM-A, junctional adhesion molecule A. D, immunofluorescent staining for ZO-1 in siRNA-transfected (for 48 h) keratinocyte monolayers ± APC (1 μg/ml) for the last 4 h. Scale bar, 20 μm. E, keratinocytes treated with Tie2 or PAR-1 siRNA (10 nm, 48 h), Tie2 inhibitor, or PAR-1 antagonist (2.0 and 1 μm, respectively, 24 h) ± APC (1 μg/ml) for the last 24 h. ZO-1 was detected by Western blotting in cell lysates. The images in C–E represent one of three experiments.

Junction proteins are important components of the epidermal barrier. Western blot analysis showed that APC treatment rapidly enhanced the expression of ZO-1, VE-cadherin, and claudin-1, three important proteins that maintain the epidermal barrier (Fig. 2C). APC not only stimulated ZO-1 but also relocated it to points of cell-cell contact that formed distinct staining around the cell periphery (Fig. 2D). Suppression of Tie2 or PAR-1 by siRNA (supplemental Fig. S1A for siRNA efficacy) or inhibitors reduced ZO-1 expression (Fig. 2E) and disrupted ZO-1 staining around the cell borders (Fig. 2D). The selectivity of APC for these junctional proteins was shown by the finding that it did not affect junctional adhesion molecule A or occludin (Fig. 2C).

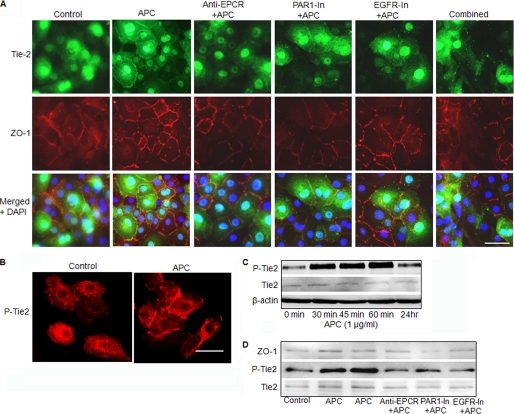

APC Induces Tie2 Translocation to Cell-Cell Contacts via EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR

Human keratinocyte monolayers incubated with basal medium for 3 days were used to analyze Tie2 in conditions that resemble the quiescent epidermis. After stimulation with APC (1 μg/ml) for 60 min, Tie2 accumulated at the cell-cell contacts and partially co-located with ZO-1 (Fig. 3A). When keratinocytes were pretreated with the EPCR blocking antibody, RCR252 (5 μg/ml), PAR-1 inhibitor (1 μm), or EGFR inhibitor (2.0 μm), the relocalization of Tie2 to cell-cell contacts in response to APC was abolished. RCR252, PAR-1 inhibitor, and, to a lesser extent, EGFR inhibitor had a similar effect on ZO-1 localization when each was used individually (Fig. 3A). These data indicate that APC induces relocation of Tie2 and ZO-1 to cell-cell contacts via EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR. In response to APC, much of the Tie2 on the cell periphery was in its activated form (P-Tie2) (Fig. 3B). Western blot analysis of keratinocyte lysates showed that APC activated Tie2 within 30 min, to a level approximately four times higher than the control (Fig. 3C). This activation reached a peak after 1 h and remained elevated by 2-fold at 24 h. No stimulation of total Tie2 by APC was found within 24 h (Fig. 3C). In addition, there was no difference observed in control within 24 h (supplemental Fig. S1B).

FIGURE 3.

APC induces Tie2 activation and translocation to cell-cell contacts via EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR. A, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with APC (1 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of EPCR blocking antibody RCR252 (anti-EPCR, 5 μg/ml), PAR-1 antagonist (1 μm, PAR1-In), EGFR inhibitor (2.0 μm, EFGR-In), or all inhibitors (Combined) for 1 h, then cells were fixed, and Tie2 and ZO-1 were detected by immunofluorescent staining. B, P-Tie2 in keratinocytes in the presence or absence of APC (1 μg/ml) for 1 h and detected by immunofluorescent staining. Scale bars, 15 μm. C, P-Tie2 and Tie2 expression in cell monolayers in response to APC treatment for different time periods, detected by Western blotting. D, ZO-1, P-Tie2, and Tie2 expression in cell membrane fraction in response to APC in the presence or absence of EPCR blocking antibody RCR252 (anti-EPCR, 5 μg/ml), PAR-1 antagonist (1 μm, PAR1-In), and EGFR inhibitor (2.0 μm, EFGR-In).

To further confirm the action of APC on relocalization of ZO-1, P-Tie2, and Tie2, cell membrane fractions were extracted and subjected to Western blotting. The results showed that there was considerably more ZO-1, P-Tie2, and Tie2 in the membrane fractions in response to APC treatment (Fig. 3D). Blocking either EPCR, PAR-1, or EGFR abolished the effect of APC (Fig. 3D).

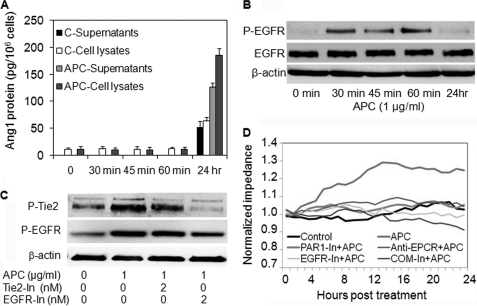

EGFR, not Ang1, Is Responsible for Effect of APC on Early Tie2 Activation

Ang1 and Ang2 are the two major ligands for Tie2, and we have previously shown that APC acts through Ang1 to activate Tie2 in endothelial cells (20). To determine whether a similar mechanism occurred in keratinocytes, cell monolayers were treated with APC over a period of 0 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, and 24 h, and culture supernatants and lysates were assayed for Ang1 and Ang2 protein levels. There was no detectable Ang2 in keratinocyte culture supernatants or cell lysates at any time point (data not shown). Ang1 was increased in culture supernatants after 24 h but was not affected by APC treatment for up to 60 min (Fig. 4A). Thus, the rapid APC-induced activation of Tie2 within 1 h is likely to occur via a process independent of Ang1.

FIGURE 4.

EGFR, not Ang1, is responsible for rapid Tie2 activation by APC. A and B, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with or without APC (1 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods. A, Ang1 protein was measured in supernatants and lysates by ELISA. B, EGFR and P-EGFR in whole cell lysates were detected by Western blotting. C, confluent keratinocytes were treated with APC ± Tie2 or EGFR inhibitors for 1 h. P-Tie2 and P-EGFR in cell lysates were detected by Western blotting. D, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with or without APC (1 μg/ml) ± EPCR blocking antibody RCR252 (anti-EPCR, 5 μg/ml), PAR-1 antagonist (PAR1-In, 1 μm), EGFR inhibitor (EFGR-In, 2.0 μm), or all inhibitors together (COM-In). The normalized impedance of cell monolayers over 24 h was measured. The graph is representative of three experiments.

To explore the mechanism of Tie2 activation, we examined EGFR, which we have previously shown to be involved in APC stimulation of keratinocyte survival and proliferation (16). Keratinocyte EGFR was activated rapidly by APC in a similar pattern to P-Tie2 (Fig. 4B). Next, confluent keratinocytes were pretreated with either Tie2 or EGFR inhibitor, and the activation of each receptor was examined by Western blot in response to APC treatment (Fig. 4C). The results showed that blocking Tie2 did not affect EGFR activation; however, blocking EGFR almost completely suppressed Tie2 activation by APC (Fig. 4C), indicating that APC regulates Tie2 activation via EGFR. Furthermore, inhibition of EGFR abolished the induction of electrical impedance induced by APC (Fig. 4D). Inhibition of EPCR or PAR-1 had a similar effect (Fig. 4D). However, the impedances of cell monolayers treated with inhibitors without APC at the indicated concentrations did not show any differences when compared with control (supplemental Fig. S1C).

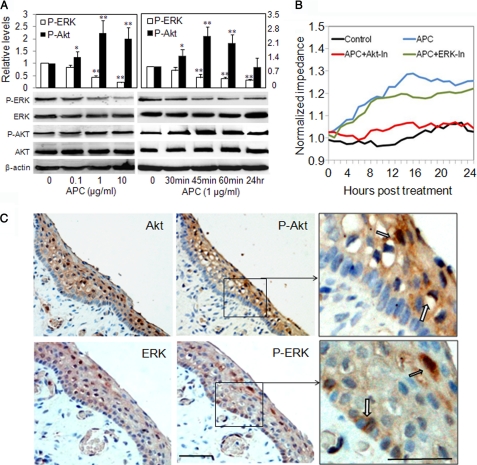

APC Activation of Tie2 Signals through Akt in Keratinocyte Monolayers

Activation of Akt promotes cell survival, whereas ERK activation leads to proliferation and migration (23, 24). Both of these signaling pathways have been implicated in the downstream signaling of Tie2 activation in endothelial cells (9). In confluent keratinocytes, APC stimulated the activation of Akt after 30 min and peaked at 45 min (Fig. 5A). Opposing its effect on Akt, APC suppressed the activation of ERK (Fig. 5A), down to ∼50% of control after 45 min. APC dose-dependently suppressed the activation of ERK, with P-ERK being reduced by ∼80% following 10 μg/ml APC treatment (Fig. 5A). In contrast, APC dose-responsively stimulated P-Akt following 1 h of treatment, showing a ∼2-fold increase when used at 1 μg/ml (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of Akt, but not ERK, abolished the APC-induced increase in impedance (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

APC activation of Tie2 and enhancement of keratinocyte barrier function signals through Akt. A, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with APC at different concentrations or for indicated times. The cell lysates were collected for Western blotting to detect P-ERK, P-Akt, total ERK, and Akt. The images were semi-quantitated by image analysis software. The data on the graph are shown as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 when compared with control (0). B, keratinocyte monolayers were treated with APC (1 μg/ml) ± kinase inhibitors for Akt (Akt-In, 1 μm) or ERK (ERK-In, 5 μm). The normalized impedance of cell monolayers over 24 h was measured. The graph is representative of three experiments. C, Akt, P-Akt, ERK, and P-ERK on foreskin epidermis were detected by immunostaining. The block arrows indicate positive staining. Scale bars, 50 μm. The images represent one of three experiments.

Using immunohistochemical staining of neonatal epidermis, we found that both Akt and P-Akt were largely associated with nuclei of upper layers of the epidermis, with a notable absence of P-Akt in the single basal proliferating layer of epidermis (Fig. 5C). In contrast, P-ERK was mainly localized in the basal layer and an upper layer of epidermis (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

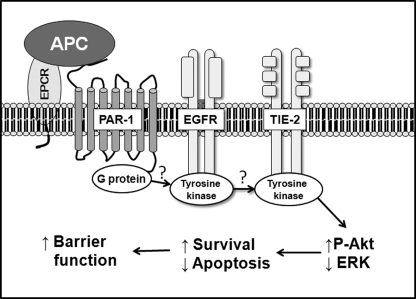

We demonstrate that APC enhances the barrier function of cultured human keratinocyte monolayers via regulation of Tie2 and subsequent activation of Akt. These functions of APC are achieved through the coordination of three receptors EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR (Fig. 6). EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR are expressed and co-localized in basal and suprabasal keratinocytes in human skin epidermis (15, 25, 26). EPCR does not signal but acts by spatially locating APC to cleave the G protein-coupled receptor, PAR-1. EGFR, a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, is vital for the development of the epidermis and its appendages (27). In normal epidermis, EGFR contributes to keratinocyte growth, migration, and suppression of terminal differentiation (27, 28). Activation of EGFR occurs when specific tyrosine residues in its C-terminal cytoplasmic domain are phosphorylated. Accumulating evidence shows that EGFR not only mediates responses to EGF-like ligands but is also a major transducer of diverse signaling systems and a switch point for cellular communication networks (27, 29).

FIGURE 6.

Proposed signal pathway for the protective role of APC on barrier function in confluent keratinocytes. APC binds to EPCR, which cleaves PAR-1. This G protein transactivates EGFR, which may further transactivate Tie2 receptor, although the mechanism of activation is unclear. This triple receptor action results in increased ZO-1 phosphorylation of Akt via PI3K and inhibition of ERK, leading to an increase in keratinocyte survival and barrier function.

APC acts via EPCR and EGFR to inhibit migration of human peripheral blood lymphocytes (30) and to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation (16). In the current study, we find that APC can rapidly activate EGFR within 30 min. There are a number of possible ligands, including EGF and TGF-α, that can phosphorylate EGFR (27); however, APC is likely to act via an alternative means such as transactivation of EGFR by utilizing PAR-1 in early stage. Signaling pathways linking PARs and EGFR have been revealed in various cell types. Thrombin activation of PAR-1 in cardiac fibroblasts leads to intracellular transactivation of EGFR, through rapid phosphorylation of phospholipase C, formation of inositol polyphosphate 3, and mobilization of intracellular calcium resulting in activation of Src and Fyn kinases, which associate with and activate EGFR tyrosine kinase (31). An alternative pathway termed “triple-membrane passing signal” has been proposed in which a G protein-coupled receptor activates an ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase), which in turn releases an EGFR ligand, such as EGF, to activate EGFR (32, 33). Although the exact mechanism of APC activation of EGFR needs further investigation, by acting together the three receptors, EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR, comprise a potentially powerful regulator of the biological functions of APC in keratinocytes.

Tie2 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that is expressed mainly by endothelial cells but has been found on other cell types, such as carcinoma cells, fibroblasts, and mural cells (8). The expression of Tie2 protein by nonmutant healthy human primary keratinocytes has been clearly identified for the first time in the current study. Activation of Tie2 by Ang1 on endothelial cells can improve blood vessel stability and, in the presence of VEGF, mediate angiogenesis (34). Although APC can stimulate Ang1 in endothelial cells (20) and keratinocytes (Fig. 4A), our data here show that APC activates Tie2 prior to Ang1 being released from the cells. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, it is feasible that EGFR tyrosine kinase auto-activates the Tie2 tyrosine kinase, in a similar manner to how EGFR itself is transactivated (33).

The MAPK pathway is a prerequisite for growth factor-stimulated mitogenesis in many cell types (35). Three major downstream MAPK cascades are ERK1/2, p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Signaling through ERK primarily enhances keratinocyte proliferation (36). Ang1/Tie2 signaling can increase phosphorylation of ERK1/2 through PI3K (37). APC acts through ERK1/2 to promote keratinocyte proliferation; however, in the current study, we show that APC inhibits P-ERK in cultured nonproliferating keratinocyte monolayers and does not act through ERK to stabilize the keratinocyte barrier. These results are in agreement with a recent study on endothelial cells, which shows that when cell-cell adhesions are disrupted, extracellular matrix-anchored Tie2 activates ERK, which preferably induces cell migration and proliferation (10). However, in confluent endothelial cells, Tie2 accumulates at cell-cell contacts and preferentially activates Akt, resulting in cell survival (10). Akt represents the major angiogenic signaling pathway downstream of Ang1/Tie2 (38). Ang1 activates PI3K and subsequently induces phosphorylation of Akt, which plays essential roles in cell survival and chemotaxis, angiogenesis, and barrier stability (8, 39, 40). Akt has three isoforms: Akt1 (usually referred to as Akt), Akt2, and Akt3. Activity of Akt and Akt2 has been implicated in controlling differentiation of various tissues in mice including muscle, adipose tissue, bone, and skin (41). Mice lacking both Akt and Akt2 display translucent skin with reduced hair follicles and a reduced number of cells in each epidermal layer (41). Knockdown of Akt in reconstituted human epidermis results in premature keratinocyte apoptosis and an abnormal epidermis in skin cultures (42). Akt blocks apoptosis by phosphorylating and thereby inactivating the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member BAD (43). Targeted disruption of Akt causes increased cell death in differentiating keratinocytes (41). The data presented here show that in confluent keratinocytes, P-Akt is (i) expressed in all epidermal layers except the basal layer, (ii) dose-dependently increased in response to APC, and (iii) required for APC-induced increase in monolayer impedance. These findings support AKT as a key signaling component in APC-induced keratinocyte barrier integrity.

Transgenic mice overexpressing Tie2 develop a psoriasis-like disease, which is characterized by breakdown of the epithelial barrier (44). Interestingly, keratinocyte-specific but not endothelial cell-specific transgenic overexpression of Tie2 leads to the development of psoriasis (45). In agreement with these laboratory results, Tie2 and its ligands are highly expressed in involved human psoriatic skin compared with uninvolved skin (46, 47). However, these studies (46, 47) did not examine whether Tie2 was activated in the psoriatic epidermis. In the current study, APC increased Tie2 activation and translocation to the cell periphery but did not enhance the overall amount of Tie2 expressed by keratinocytes (Fig. 3C). Together, these findings suggest that the downstream effects of Tie2 differ depending on its absolute amount and activity.

In summary, we report that human keratinocytes express the endothelial receptor Tie2 and that APC promotes skin barrier protection via this receptor. In addition, we reveal a complex array and sequence of receptor activation of Tie2, involving EPCR, PAR-1, and EGFR (Fig. 6), the exact mechanism of which needs further investigation. Moreover, activation of Tie2 selectively promotes PI3K/Akt signaling to enhance junctional complexes and reduce keratinocyte permeability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The foreskins were provided by Dr. Gordon Campbell (Sydney Adventist Hospital). We thank Susan Smith for preparation of foreskin tissue sections, Dr. Mike Lin and Gang Lu for help in membrane protein extraction, Dr. Kaley Whitmont for adult skin sections, and Nikita Minhas for some general help.

This work was supported by a career development award and a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- Ang

- angiopoietin

- ZO

- zona occludens

- APC

- activated protein C

- EPCR

- endothelial protein C receptor

- PAR

- protease-activated receptor

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- ECIS

- electric cell substrate impedance sensing

- P-Tie2

- phosphorylated Tie2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Proksch E., Brandner J. M., Jensen J. M. (2008) Exp. Dermatol. 17, 1063–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koster M. I. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 7–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Honari S. (2004) Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. North. Am. 16, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vandenbroucke E., Mehta D., Minshall R., Malik A. B. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1123, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandner J. M. (2009) Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 72, 289–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furuse M., Hata M., Furuse K., Yoshida Y., Haratake A., Sugitani Y., Noda T., Kubo A., Tsukita S. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 1099–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fiedler U., Augustin H. G. (2006) Trends Immunol. 27, 552–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makinde T., Agrawal D. K. (2008) J. Cell Mol. Med. 12, 810–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fukuhara S., Sako K., Noda K., Nagao K., Miura K., Mochizuki N. (2009) Exp. Mol. Med. 41, 133–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fukuhara S., Sako K., Minami T., Noda K., Kim H. Z., Kodama T., Shibuya M., Takakura N., Koh G. Y., Mochizuki N. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 513–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters K. G., Kontos C. D., Lin P. C., Wong A. L., Rao P., Huang L., Dewhirst M. W., Sankar S. (2004) Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 59, 51–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson C. J., Xue M. (2008) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2692–2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mosnier L. O., Zlokovic B. V., Griffin J. H. (2007) Blood 109, 3161–3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xue M., Thompson P., Kelso I., Jackson C. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 299, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xue M., Campbell D., Sambrook P. N., Fukudome K., Jackson C. J. (2005) J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 1279–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xue M., Campbell D., Jackson C. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13610–13616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feistritzer C., Riewald M. (2005) Blood 105, 3178–3184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finigan J. H., Dudek S. M., Singleton P. A., Chiang E. T., Jacobson J. R., Camp S. M., Ye S. Q., Garcia J. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17286–17293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xue M., Minhas N., Chow S. O., Dervish S., Sambrook P. N., March L., Jackson C. J. (2010) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 67, 1537–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Minhas N., Xue M., Fukudome K., Jackson C. J. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 873–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCarthy K. M., Francis S. A., McCormack J. M., Lai J., Rogers R. A., Skare I. B., Lynch R. D., Schneeberger E. E. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 3387–3398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Candi E., Schmidt R., Melino G. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 328–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manning B. D., Cantley L. C. (2007) Cell 129, 1261–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pouysségur J., Volmat V., Lenormand P. (2002) Biochem. Pharmacol. 64, 755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piepkorn M., Predd H., Underwood R., Cook P. (2003) Arch. Dermatol. Res. 295, 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Materazzi S., Pellerito S., Di Serio C., Paglierani M., Naldini A., Ardinghi C., Carraro F., Geppetti P., Cirino G., Santucci M., Tarantini F., Massi D. (2007) J. Pathol. 212, 440–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jost M., Kari C., Rodeck U. (2000) Eur. J. Dermatol. 10, 505–510 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jost M., Huggett T. M., Kari C., Boise L. H., Rodeck U. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6320–6326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carpenter G. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146, 697–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feistritzer C., Mosheimer B. A., Sturn D. H., Riewald M., Patsch J. R., Wiedermann C. J. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 1019–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sabri A., Short J., Guo J., Steinberg S. F. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fischer O. M., Hart S., Gschwind A., Ullrich A. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1203–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pastore S., Mascia F., Mariani V., Girolomoni G. (2008) J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 1365–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Findley C. M., Cudmore M. J., Ahmed A., Kontos C. D. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 2619–2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roux P. P., Blenis J. (2004) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 320–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eckert R. L., Efimova T., Dashti S. R., Balasubramanian S., Deucher A., Crish J. F. (2002) J. Invest. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 7, 36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harfouche R., Gratton J. P., Yancopoulos G. D., Noseda M., Karsan A., Hussain S. N. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 1523–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeBusk L. M., Hallahan D. E., Lin P. C. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 298, 167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Babaei S., Teichert-Kuliszewska K., Zhang Q., Jones N., Dumont D. J., Stewart D. J. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 1927–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim I., Kim H. G., Moon S. O., Chae S. W., So J. N., Koh K. N., Ahn B. C., Koh G. Y. (2000) Circ. Res. 86, 952–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peng X. D., Xu P. Z., Chen M. L., Hahn-Windgassen A., Skeen J., Jacobs J., Sundararajan D., Chen W. S., Crawford S. E., Coleman K. G., Hay N. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1352–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thrash B. R., Menges C. W., Pierce R. H., McCance D. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12155–12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Datta S. R., Brunet A., Greenberg M. E. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 2905–2927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Voskas D., Jones N., Van Slyke P., Sturk C., Chang W., Haninec A., Babichev Y. O., Tran J., Master Z., Chen S., Ward N., Cruz M., Jones J., Kerbel R. S., Jothy S., Dagnino L., Arbiser J., Klement G., Dumont D. J. (2005) Am. J. Path. 166, 843–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wolfram J. A., Diaconu D., Hatala D. A., Rastegar J., Knutsen D. A., Lowther A., Askew D., Gilliam A. C., McCormick T. S., Ward N. L. (2009) Am. J. Path. 174, 1443–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuroda K., Sapadin A., Shoji T., Fleischmajer R., Lebwohl M. (2001) J. Invest. Dermatol. 116, 713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Markham T., Mullan R., Golden-Mason L., Rogers S., Bresnihan B., Fitzgerald O., Fearon U., Veale D. J. (2006) J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.