Abstract

The opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.) is one of the oldest known medicinal plants. In the biosynthetic pathway for morphine and codeine, salutaridine is reduced to salutaridinol by salutaridine reductase (SalR; EC 1.1.1.248) using NADPH as coenzyme. Here, we report the atomic structure of SalR to a resolution of ∼1.9 Å in the presence of NADPH. The core structure is highly homologous to other members of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. The major difference is that the nicotinamide moiety and the substrate-binding pocket are covered by a loop (residues 265–279), on top of which lies a large “flap”-like domain (residues 105–140). This configuration appears to be a combination of the two common structural themes found in other members of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. Previous modeling studies suggested that substrate inhibition is due to mutually exclusive productive and nonproductive modes of substrate binding in the active site. This model was tested via site-directed mutagenesis, and a number of these mutations abrogated substrate inhibition. However, the atomic structure of SalR shows that these mutated residues are instead distributed over a wide area of the enzyme, and many are not in the active site. To explain how residues distal to the active site might affect catalysis, a model is presented whereby SalR may undergo significant conformational changes during catalytic turnover.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Enzyme Structure, Plant, Protein Structure, Reductase, Morphine

Introduction

The narcotic analgesic morphine and the antitussive codeine are the most important active alkaloids from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.). The tetracyclic morphinan salutaridine is an intermediate in morphine and codeine biosynthesis. P. somniferum salutaridine reductase (SalR2; EC 1.1.1.248) reduces the C-7 keto group of salutaridine to the C-7 S-configuration hydroxyl group of salutaridinol using the 4-pro-S-hydride of NADPH. Only the S-configuration of salutaridinol is biologically active, as demonstrated by its transformation to morphine and codeine in vivo (1, 2). SalR was purified from a plant cell culture and characterized by Gerardy and Zenk (3). The SalR cDNA was identified during a cross-species comparison of gene expression profiles between 16 different Papaver species (4).

SalR belongs to the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family. The SDR family of proteins has a single domain composed of a parallel α/β-fold with a Rossmann fold motif for NAD(P)(H) binding. A central twisted parallel β-sheet is flanked by three α-helices on each side (5). Among the known structures of proteins belonging to the SDR family, human CBR1 (carbonyl reductase 1) has the highest sequence identity to SalR (105 of 311 amino acid residues) (6, 7) and is a drug-metabolizing enzyme. Human carbonyl reductases react with a number of organic compounds such as steroids, prostaglandins, xenobiotics, and S-nitrosoglutathione (8–10). In contrast, salutaridine is the only known substrate of plant-derived SalR (3, 4). SalR has a 36-residue insertion (Ser105–Glu140) that does not exist in animal carbonyl reductases. This insertion is found in other members of the SDR family in plants, but none of the atomic structures of these enzymes were yet determined.

The medicinal significance of morphine and codeine makes their biosynthetic pathway an important biotechnological target. Optimization or alteration of the morphine biosynthetic pathway requires detailed knowledge of the structures of the individual catalysts. Here, we report the structure of P. somniferum SalR complexed with NADPH. Computer simulations were performed to dock the substrate into the binary complex, and the resulting model agrees well with known biophysical parameters. The 36-residue insert, unique to SalR among the SDR family, forms a “flap”-like domain that covers the substrate-binding site, which may undergo conformational changes during catalysis. A cluster of exposed cysteine residues at the C terminus may account for the inactivation of SalR under oxidative conditions, but the biological role of this region is unclear. Finally, the atomic model disagrees with previously published modeling studies that suggested that substrate inhibition is due to a second substrate-binding site. Instead, a model is proposed whereby substrate inhibition may be a consequence of relatively slow conformational changes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Selenomethionine-substituted SalR

Selenomethionine (SeMet)-substituted SalR was produced by inhibition of the methionine biosynthetic pathway (11, 12) with the same expression vector and Escherichia coli strain used for expression of native SalR (13). Transformed E. coli was grown at 37 °C in M9 medium supplemented with 0.015 mm thiamine and 50 μg/ml kanamycin until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.6. The culture was cooled to 4 °C for 1 h. Each flask was supplemented with 100 mg each of l-lysine, l-threonine, and l-phenylalanine and 50 mg each of l-leucine, l-isoleucine, l-valine, and l-selenomethionine. After 30 min of growth at 16 °C, the protein was induced with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The culture was grown for 16 h at 16 °C. SeMet-substituted SalR was purified in an identical manner as native SalR via cobalt affinity and size-exclusion chromatography (13). The N-terminal His tag was cleaved by thrombin before the size-exclusion chromatography. Purified SalR was dialyzed against 20 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mm NaCl and 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and concentrated to 12 mg/ml with a Centriprep YM-10 filter (Millipore) prior to storage at −80 °C. The protein yield was 3.8 mg/liter of culture. The purity of SeMet-substituted SalR was ascertained using 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The enzyme activity of purified SalR was confirmed by HPLC as described previously (13).

Crystallization of SeMet-substituted SalR

SeMet crystals were obtained using the hanging-drop method as described previously for native SalR (13). In brief, the reservoir solution contained 0.1 m MES (pH 6.0–6.6), 1.9 m ammonium sulfate, 5% (v/v) PEG 400, 0.1 m LiCl, and 3% (v/v) glycerol. Two microliters of 6 mg/ml SeMet-substituted SalR containing 4 mm NADPH was mixed with 2 μl of the reservoir solution for the hanging drop. Crystals formed after 3 weeks at 4 °C. SeMet-substituted SalR crystals were flash-frozen as described previously (13).

X-ray Structure Determination

Diffraction maxima for all three data sets were collected on a 3 × 3 tiled SBC3 CCD detector at the Structural Biology Center 19-BM beamline (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL). X-ray data were processed with HKL3000 and scaled with SCALEPACK (14). Data collection statistics are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

PDB, Protein Data Bank.

| Data collection | |

| Structure | SeMet-substituted SalR |

| PDB code | 3O26 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97970 |

| Data resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.91 (1.94-1.91) |

| Total reflections | 836,117 (7928) |

| No. independent reflections | 40,176 (1802) |

| Completeness | 94.3 (68.0) |

| Redundancy | 19.6 (4.4) |

| Average I/average s(I) | 77.5 (4.7) |

| Rsym (%) | 5.9 (27.9) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Refinement resolution (Å) | 50-1.91 (1.96-1.91) |

| No. non-solvent atoms | 2305 |

| No. solvent atoms | 262 |

| Rwork | 20.1 (22.2) |

| No. reflections | 38,027 (2149) |

| Rfree (%) | 22.5 (23.1) |

| Average B non-solvent atoms (Å2) | 33.4 |

| Average B solvent atoms (Å2) | 40.4 |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.006 |

| Bond angle | 1.10° |

| Ramachandran analysis | |

| Most favored region (%) | 92.0 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 8.0 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 |

The structure of SalR was determined using single-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing from the x-ray data collected from crystals of SeMet-substituted SalR co-crystallized with NADPH. The programs SHELXD and SHELXE (15) were used to determine the initial positions of the selenomethionines, to distinguish between the P6422 and P6222 space groups, and to estimate the initial phases from the peak wavelength data set. The heavy atom positions and parameters were further refined using MLPHARE from the CCP4 suite of programs (16). Solvent flattening was performed using DM (17, 18), and ARP/wARP (19) was used for initial model building. Alternate cycles of manual model building in Coot (20) with maximum likelihood refinement using Phenix (21) were then used to build and refine the 1.9-Å SeMet-substituted SalR structure. The final geometry was analyzed using PROCHECK (22).

Modeling of Substrate Binding

The program AutoDock 4 (23) was used to model salutaridine into the active-site pocket. The program was applied using standard protocols that are well described in accompanying documentation. The protein complex (SalR plus the bound NADPH molecule) was treated as a rigid body while the program was used to detect active torsion angles in the substrate and to calculate the charges of both the ligand and the protein. Salutaridine was placed into the general region where the substrate was expected to bind, and a search box of 40 × 40 × 40 Å was centered at this location. The docking was performed using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm.

RESULTS

Atomic Structure of SalR

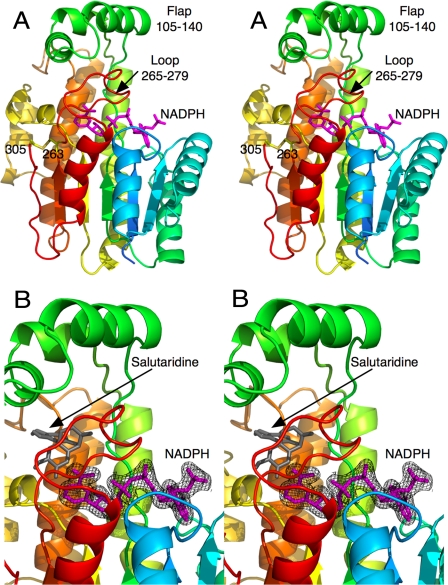

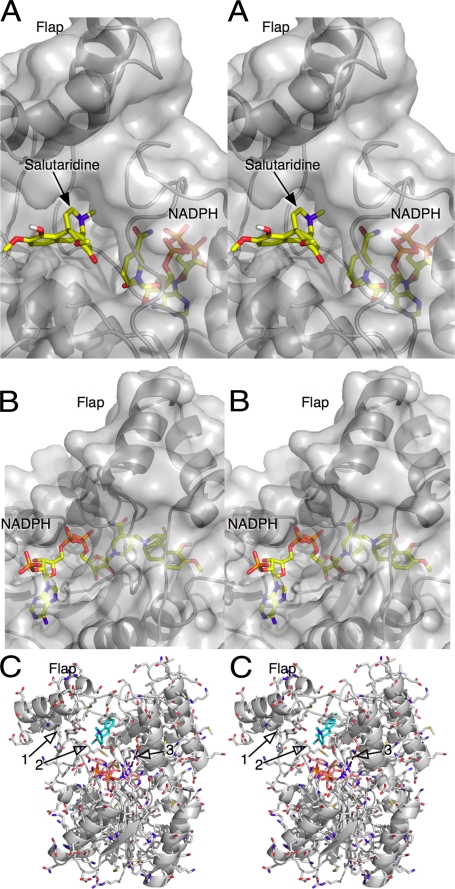

In the final SalR model, electron density was visible only for residues 12–305. Although there was weak density for the last six residues at the C terminus, the density was too diffuse for accurate model building. The final Rwork was 20.1%, and the final Rfree was 22.5%. The model contains 262 water molecules in addition to the bound NADPH. The majority of SalR is composed of the conserved SDR domain (Fig. 1). The bound NADPH was clearly visible in the electron density and has an extended conformation on top of the SDR domain. The bound coenzyme lies under the loop extending from the top of the SDR domain (residues 265–279), which, in turn, lies under a unique flap-like domain composed of residues 105–140.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of SalR. A, stereo image of the structure of SalR looking into the active site. The ribbon is colored from blue to red as the amino acid chain extends from the N to the C terminus. The structure of the bound NADPH is represented by a mauve stick figure. B, close-up of the active site showing the electron density of the bound NADPH molecule. As a reference, the modeled salutaridine is shown as a gray stick figure.

The last residue with clear electron density, Cys305, forms a disulfide bond with Cys263. Residues immediately upstream from the Cys305 disulfide bond (positions 298–305) form some backbone interactions with β-strand 258–263 that could allow it to be part of the parallel β-sheet in the canonical SDR domain. However, residue 301 forms a bulge that disrupts much of the backbone hydrogen bonds necessary for a proper β-sheet. In this conformation, it appears that the disulfide bond is stabilizing what appears to be fairly weak interaction between these two strands. Because the cytoplasm where SalR resides is a reductive environment, it is not at all clear whether this disulfide bond exists in vivo.

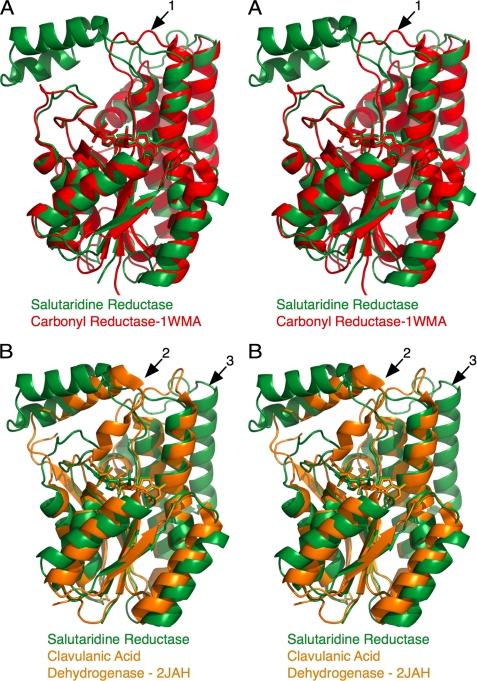

As shown in Fig. 2, the SDR domain in SalR is highly conserved compared with other SDR family members, but the decorations at the top of the SDR domain have notable differences. Rather than the large flap domain observed in SalR, carbonyl reductase has a short loop over the substrate-binding pocket (Fig. 2A, arrow 1). The loop in SalR that covers the nicotinamide moiety (residues 265–279) has a very similar conformation to that of carbonyl reductase (residues 230–240). Clavulanic acid dehydrogenase is similar to SalR in that it has a flap-like domain over the substrate-binding site. However, the flap in clavulanic acid dehydrogenase (residues 190–210) extends from the equivalent “loop” region in SalR (residues 265–279) discussed above (Fig. 2B, arrow 2). Therefore, this flap domain in SalR, which extends from the back of the SDR domain, is unique to SalR. The other major difference between SalR and clavulanic acid dehydrogenase is that SalR has the two additional α-helices at the back of the SDR domain (Fig. 2B, arrow 3). As noted previously with other SDR structures (24), these additional helices likely block the oligomerization observed in clavulanic acid dehydrogenase.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of the structure of SalR with those of other short chain reductases. A, stereo diagram of an overlay of SalR (green) with carbonyl reductase (35). B, alignment of SalR (green) with clavulanic acid dehydrogenase (24).

Modeling the Conformation of Bound Salutaridine

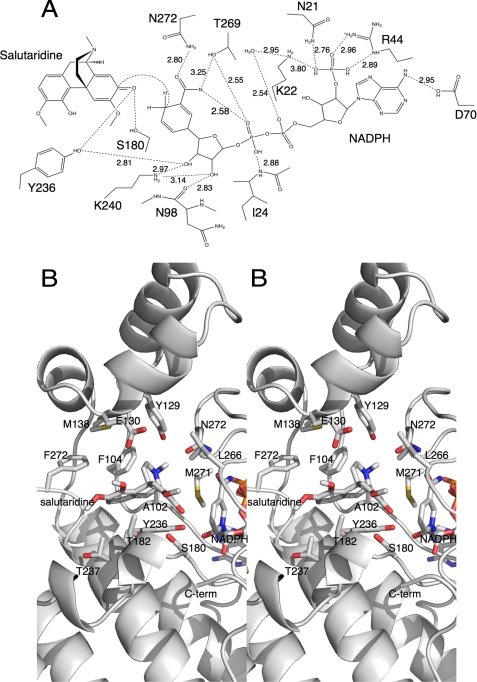

The binding of salutaridine was modeled using AutoDock 4 (Fig. 3) following the detailed instructions in the manual. The lowest energy cluster yielded a binding energy of ∼8 kcal/mol with a calculated binding constant of ∼9 μm. Almost all of the calculated binding energy came from the van der Waals hydrophobic desolvation Gibbs free energy term. This calculated binding constant is almost identical to the previously published Km values (25). More importantly, this cluster of best docking solutions places the substrate in the correct orientation for catalysis (Figs. 1 and 3). In this orientation, the reactive carbonyl of salutaridine is within ∼4 Å of the C-4 atom of the bound nicotinamide ring (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, it is at the appropriate distances from the previously described catalytic triad of the SDR family (26). Together, these results strongly suggest that the AutoDock results are quite accurate.

FIGURE 3.

Interactions between SalR and its substrate and coenzyme. A, schematic of the possible hydrogen bonding interactions with the modeled bound salutaridine. B, stereo image of the binding environment of the modeled salutaridine. In this view, the flap domain is toward the top, and the SDR domain is toward the bottom.

Although the flap domain is unique to SalR and lies over the substrate-binding domain, it actually contributes in a minor way to substrate/protein interactions. Most of the contributions to the substrate-binding pocket come from residues in the linker regions extending into and out of the flap region (Fig. 3B). For example, Phe104 is on the ascending strand extending into the flap and contributes to the hydrophobic surface on the back of the substrate pocket. Met138 is on the descending strand from the flap domain and contributes to the hydrophobic upper surface of the substrate-binding domain. The one residue in the flap domain that does interact with salutaridine is Tyr129, where the tyrosine hydroxyl moiety is in close proximity to the salutaridine nitrogen atom. Therefore, for the most part, the residues necessary to form the substrate-binding pocket could have been supplied by a much smaller domain such as that found in carbonyl reductase. It is not at all clear why such an elaborate domain was created in the case of SalR, but it could be involved in channeling salutaridinol to the next enzyme in the pathway (salutaridinol 7-O-acetyltransferase as suggested by yeast-two hybrid and co-immunoprecipitation analyses (27).

Buried Coenzyme

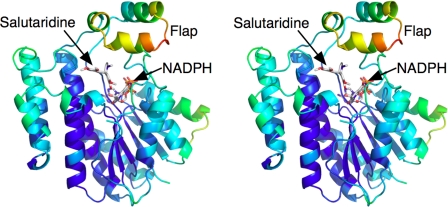

There are several lines of evidence to suggest that there might be significant conformational changes in SalR during catalysis. As shown in Fig. 4, the flap region has significantly higher B values than the rest of the enzyme. This suggests that the entire domain is rather motile. It is also apparent that the bound NADPH is extensively buried by the surrounding protein. Residues 265–279 form a loop on top of the main SDR domain that covers much of the nicotinamide ribose moiety. On top of this loop lies the flap domain, which also forms the upper hydrophobic surface of the substrate-binding pocket. When viewed as a molecular surface (Fig. 5), the substrate binds into a deep pocket that is accessible to the bulk solvent. However, both ends of NADPH are buried by protein, and only the middle ribose phosphate portion of the molecule is exposed. Therefore, either NADPH must be binding by “worming” into the narrow binding pocket, or there may be concerted conformational changes in SalR that expose the coenzyme-binding site. In the case of the latter, large domain movements have been observed in other dehydrogenases (e.g. Refs. 28 and 29). It is interesting to note that SalR crystallized only in the presence of NADPH, suggesting that the coenzyme might induce a “closed” conformation necessary for crystal packing. However, the nature of such conformational motion is unclear because there are such extensive protein/protein interactions between loop 265–279 and the bottom of the flap domain (Fig. 5C, arrow 1).

FIGURE 4.

Possible flexible regions of SalR. Shown is a ribbon diagram of SalR color-coded according to B values; the color gradient changes from blue to red with increasing B factors.

FIGURE 5.

Buried nature of the bound NADPH. A, frontal view of the active site with the molecular surface of the protein shown in transparent gray. Note how the salutaridine-binding pocket is a deep exposed pocket under the flap, whereas the nicotinamide portion of NADPH is nearly buried by the flap and loop 265–279 region. B, rear view of the active site showing how nearly all of the bound NADPH is covered by SalR. The only exposed portion of the molecule is the phosphate ribose moiety adjacent to the adenosine. C, details of the loop region under the flap domain, which may move during each catalytic cycle.

Location and Effects of SalR Mutations

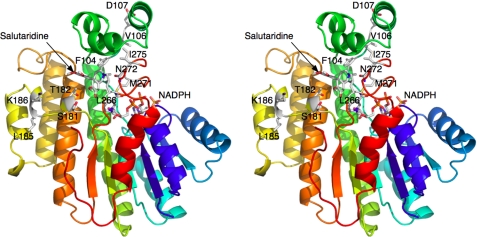

In a previous study (30), a homology modeling and mutagenesis study was performed on SalR. From this analysis, it was suggested that the apparent substrate inhibition observed at high salutaridine concentrations is due to a second, nonproductive, and overlapping binding mode in the active site. This model was then tested via a number of mutations around these two proposed binding modes. A summary of these mutations is reviewed in Table 2, and the actual locations of the mutations are mapped onto the SalR structure in Fig. 6.

TABLE 2.

Locations of previously characterized SalR mutations and their effects on Km and kcat (30)

| Mutation | Km ratio | kcat ratio | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | |||

| M271A | 11 | 0.0046 | Lies over nicotinamide ring and near substrate |

| N272A | 43 | 0.016 | Hydrogen bonds to nicotinamide ring |

| L266A | 23 | 0.38 | Covers substrate and nicotinamide ring |

| F104A | 15 | 2.1 | Within substrate-binding pocket |

| S181A | 2.4 | 1.5 | Near, but not in contact with, substrate |

| T182A | 2.0 | 0.096 | Near bound substrate |

| Group 2 | |||

| L185A | 6.3 | 0.012 | Very distal to substrate, pointing away from pocket |

| L185S | 0.5 | 0.11 | |

| L185V | 1.0 | 0.52 | |

| K186V | 3.7 | 0.76 | Very distal to substrate, pointing away from pocket |

| Group 3 | |||

| V106A | 4.2 | 1.9 | On connector to flap domain, not in binding pocket |

| D107A | 7.0 | 0.47 | On connector to flap domain, not in binding pocket |

| I275A | 16 | 2.44 | On loop on top of coenzyme-binding domain, buried by flap |

| I275V | 1.0 | 0.78 | |

| Double mutant | |||

| F104A/I275A | 195 | 2.36 | Phe104 in substrate-binding pocket, Ile275 under flap domain |

FIGURE 6.

Locations of the previously described mutation sites (30). The orientation and coloration are as described in the legend to Fig. 1, with the side chains of the mutated residues colored according to the atom type. A summary of the effects of these mutations is provided in Table 2.

Although the homology modeling had suggested that these residues cluster immediately around the substrate-binding site, they are in fact dispersed in three general locations in SalR: the substrate-binding pocket, distal to substrate-binding pocket on the far edge of the main coenzyme-binding domain, and around the flap domain. In the first category, mutations in Met271 and Asn272 have the most profound effects on the Vmax and Km. This is not surprising because Met271 lies on top of the nicotinamide ring and is immediately adjacent to the bound substrate, and Asn272 forms hydrogen bonds with the nicotinamide moiety. It is important to note that mutations of these two residues completely abrogate apparent substrate inhibition. Similarly, mutations of Leu266 greatly affect the Km but do not affect the kcat to the same degree as the previous sites. Leu266 lies more toward the face of the enzyme but also covers the substrate and nicotinamide moiety. An F104A mutation slightly increases the kcat while increasing the Km by ∼15-fold. Phe104 helps to form a hydrophobic surface at the back of the substrate-binding pocket but, unlike the previous three residues, does not lie immediately adjacent to the nicotinamide/substrate interface. Therefore, this may be why this mutation mainly affects the apparent binding constant. The effects of mutations at Thr182 and Ser181 are more subtle and may be affecting the Km and kcat in a less direct manner. As shown in Fig. 3A, Ser180 forms a hydrogen bond with the modeled bound substrate. However, Ser181 faces the external face of the enzyme beneath the substrate-binding pocket. Therefore, it is not entirely surprising that the S181A mutation has a rather muted effect on catalysis. The T182A mutation increases the Km by only ∼2-fold but decreases the kcat by ∼10-fold. Thr182 lies at the base of the substrate-binding pocket, and mutation of this residue could affect substrate positioning. However, in both cases, these mutations may be indirectly affecting the conformation of Ser180 that is directly involved in catalysis.

The second cluster of mutations involves Leu185 and Lys186. Mutations here can increase the Km by nearly 10-fold and decrease the kcat by 100-fold. Although the homology modeling placed these residues in contact with the substrate, they are, in fact, very distal to and pointing away from the substrate-binding pocket. Because these residues are so distal to the active site, it seems most likely that mutations of Leu185 and Lys186 indirectly disrupt the active site (e.g. Ser180).

Although the third group of residues was thought to form the upper surface of the substrate-binding pocket, they are actually distal to the active site and are involved in interactions with the flap domain. Ile275 lies on top of the main coenzyme-binding domain and makes contact with the flap. When it is mutated to Ala, the Km is increased by 16-fold, and the kcat is also apparently increased by >2-fold. However, when mutated to Val, there is little effect on catalysis or apparent substrate binding. One explanation for this is that Ile275 makes necessary hydrophobic interactions with the flap (e.g. Ile115, Leu125, and Val126) that helps to form the active-site pockets. When mutated to Ala, the flap is destabilized, and both apparent substrate affinity and catalytic turnover are affected. The other two residues in this group, Val106 and Asp107, likely affect the flap in a similar manner, but the mechanism is less obvious. Both residues are very distal to the active site and lie on the ascending strand extending into the flap domain. Val106 points inward, whereas Asp107 points out into the bulk solvent. Mutating either residue to alanine has a small effect on the kcat but increases the Km by 4–7-fold. Perhaps these mutations affect the orientations of the residues immediately upstream (e.g. Phe104) that form the substrate-binding pocket, or they affect the positioning of the flap domain itself.

DISCUSSION

Comparison with Other Members of the SDR Family

The substrate-binding region of SalR appears to be a combination of two groups of the SDR family. In one group (e.g. clavulanic acid dehydrogenase, Protein Data Bank code 2JAH), there is a flap domain extending from the front of the active site in place of loop 265–279. In the other group (e.g. carbonyl reductase, code 1WMA), the flap is absent, and only the equivalent to loop 265–279 covers the active site. It is not clear why SalR has both features with loop 265–279 covered by the flap domain (positions 105–140). As noted previously, many of the residues forming the hydrophobic substrate pocket lie on the flexible linker going into and extending out of the flap domain. The presence of the flap is unlikely due to the hydrophobicity of the substrate because the carbonyl reductase has a simple loop rather than the flap domain, and the solubility of the substrate (PP2) is ∼20 μg/ml. Furthermore, clavulanic acid dehydrogenase has a similar flap domain, albeit in a different location in the amino acid sequence, and the solubility of clavulanic acid in water is >100 mg/ml.

It is important to note that SalR functions to produce morphine in the opium poppy, whereas human carbonyl reductase functions to metabolize a number of xenobiotics. The interaction between Phe104, Tyr129, and the top surface of salutaridine likely increases the substrate specificity by eliminating the possibility for SalR to metabolize flat-shaped compounds such as steroids. In this way, the flap of SalR may be a specialization of the general SDR motif to make the enzyme specific for the multi-ring morphinan structure of salutaridine. The flap may also help position the partially symmetric structure of salutaridine in the correct orientation to avoid nonproductive substrate binding.

Possible Conformational Changes Associated with Catalysis

As shown in Fig. 5, the bound NADPH is extensively buried by SalR. The question is how NADPH accesses the binding site during each catalytic turnover event. Although it is possible that the NADPH molecule might worm its way into its binding site, this is difficult to imagine because so little of the bound coenzyme is exposed to the bulk solvent (Fig. 5). In other types of dehydrogenases (e.g. glutamate dehydrogenase) (29), access to the active site is afforded by movement of large domains about flexible peptide linker regions. Among members of the SDR family, substrate binding is not necessarily associated with conformational changes. For example, no significant conformational changes were observed when substrate bound to clavulanic acid dehydrogenase (24). However, a flap-like domain at the front of the active site moves significantly upon substrate binding to 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (31). In a homologous manner, the flap region might lift, exposing loop 265–279 and making it easier to open the area around the nicotinamide ring. This is circumstantially supported by the relatively high B values for the flap domain. However, as noted by arrow 1 in Fig. 5C, there are a number of hydrophobic interactions between the flap domain and the top of the SDR domain. Therefore, this would seem to require a significant amount of energy to first lift the flap and then move loop 265–279.

Perhaps the NADPH-binding site is exposed through more subtle conformational changes. Met271 is in the middle of loop 265–279 and lies directly over the nicotinamide ribose moiety (Figs. 3, 5, and 7). Mutation of this residue to Ala has a profound effect on both the Km and kcat (Table 2) (30). Perhaps the flap region stays approximately in the same position, but the loop immediately around Met271 rotates away from the active site (toward the viewer in Fig. 5C). This could open the back of the active site to afford insertion of the nicotinamide ring into the active site. Interestingly, Arg44 (Fig. 5C, arrow 3) covers and forms a cation-π bond interaction with the adenosine ring while hydrogen bonding with Glu147 via a water molecule.

Substrate Inhibition

Previous modeling exercises (30) suggested that the substrate inhibition observed with SalR is due to two overlapping salutaridine-binding modes in the active site: one productive and one nonproductive. The model was supported by mutagenesis studies of these proposed active-site residues that eliminated substrate inhibition. In our substrate modeling studies using the SalR-NADPH structure, we did not observe a similar alternative binding mode for salutaridine. Furthermore, the atomic structure of SalR shows that a number of the residues modeled in the active site in the previous study are actually distal to the active site. Therefore, although the mutations clearly abrogate substrate inhibition, the consequences of these mutations cannot be as previously proposed.

Substrate inhibition can be a manifestation of the kinetic mechanism for the enzyme. For example, in an Ordered Bi Bi reaction, substrate can bind before the second product is released to form a dead-end complex. Indeed, such a dead-end complex was suggested in the case of human estrogenic 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (32). Nevertheless, it is difficult to understand how mutations far from the active site could affect substrate inhibition and possible dead-end complex formation.

One possible explanation is that some of these mutations affect conformational changes associated with catalysis, as has been observed with a number of dehydrogenases. For example, animal glutamate dehydrogenase exhibits strong substrate inhibition without the presence of a nonproductive substrate-binding mode (33, 34). The glutamate dehydrogenase reaction follows a rapid equilibrium, random order mechanism with the binding of substrate first being slightly favored. In this dehydrogenase, substrate inhibition is observed under conditions in which product release is the rate-limiting step. The coenzyme-binding domain in glutamate dehydrogenase undergoes a large movement during each catalytic cycle. Substrate inhibition occurs when the catalytic cleft opens sufficiently to allow product to be replaced by substrate before the reacted coenzyme can be released. The enzyme is then trapped in a tightly bound, dead-end complex, resulting in substrate inhibition. Under pH and substrate conditions that are less favorable for substrate saturation of the active site, the rate-limiting step is not product release, and substrate inhibition is not observed. Furthermore, an allosteric activator, ADP, acts by binding distal to the active site and increasing the Km (and Kd) of the substrates and coenzyme by affecting the conformational changes associated with enzyme turnover (28, 29). Therefore, the results of SalR mutagenesis are consistent with, albeit not proof of, some fairly significant conformational changes occurring during catalysis.

This work was supported by start-up funds from the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center (to T. J. S.), by the Mallinckrodt Foundation, St. Louis (to T. M. K.), and by a Uehara Memorial Foundation postdoctoral fellowship (to Y. H.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3O26) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- SalR

- salutaridine reductase

- SDR

- short chain dehydrogenase/reductase

- SeMet

- selenomethionine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barton D. H., Kirby G. W., Steglich W., Thomas G. M., Battersby A. R., Dobson T. A., Ramuz H. (1965) J. Chem. Soc. 65, 2423–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lotter H., Gollwitzer J., Zenk M. H. (1992) Tetrahedron Lett. 33, 2443–2446 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerardy R., Zenk M. H. (1993) Phytochemistry 34, 125–132 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziegler J., Voigtländer S., Schmidt J., Kramell R., Miersch O., Ammer C., Gesell A., Kutchan T. M. (2006) Plant J. 48, 177–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kavanagh K. L., Jörnvall H., Persson B., Oppermann U. (2008) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3895–3906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanaka N., Nonaka T., Tanabe T., Yoshimoto T., Tsuru D., Mitsui Y. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 7715–7730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bateman R., Rauh D., Shokat K. M. (2007) Org. Biomol. Chem. 5, 3363–3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wermuth B. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 1206–1213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bateman R. L., Rauh D., Tavshanjian B., Shokat K. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35756–35762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pilka E. S., Niesen F. H., Lee W. H., El-Hawari Y., Dunford J. E., Kochan G., Wsol V., Martin H. J., Maser E., Oppermann U. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e7113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Duyne G. D., Standaert R. F., Karplus P. A., Schreiber S. L., Clardy J. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koropatkin N. M., Pakrasi H. B., Smith T. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9820–9825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higashi Y., Smith T. J., Jez J. M., Kutchan T. M. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66, 163–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheldrick G. M. (2008) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 64, 112–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 15299374 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cowtan K. (1994) Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 31, 34–38 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terwilliger T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morris R. J., Perrakis A., Lamzin V. S. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 374, 229–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D. (2005) CCP4 Newsletter 42, 8 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris G. M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M. F., Belew R. K., Goodsell D. S., Olson A. J. (2009) J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. MacKenzie A. K., Kershaw N. J., Hernandez H., Robinson C. V., Schofield C. J., Andersson I. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 1523–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Geissler R., Brandt W., Ziegler J. (2007) Plant Physiol. 143, 1493–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jörnvall H., Persson B., Krook M., Atrian S., Gonzàlez-Duarte R., Jeffery J., Ghosh D. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 6003–6013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kempe K., Higashi Y., Frick S., Sabarna K., Kutchan T. M. (2009) Phytochemistry 70, 579–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banerjee S., Schmidt T., Fang J., Stanley C. A., Smith T. J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 3446–3456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith T. J., Stanley C. A. (2008) Trends Biol. Chem. 33, 557–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ziegler J., Brandt W., Geissler R., Facchini P. J. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26758–26767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ghosh D., Weeks C. M., Grochulski P., Duax W. L., Erman M., Rimsay R. L., Orr J. C. (1991) Biochemistry 88, 10064–10068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gangloff A., Garneau A., Huang Y. W., Yang F., Lin S. X. (2001) Biochem. J. 356, 269–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bailey J., Bell E. T., Bell J. E. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 5579–5583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith T. J., Peterson P. E., Schmidt T., Fang J., Stanley C. A. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 307, 707–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanaka M., Bateman R., Rauh D., Vaisberg E., Ramachandani S., Zhang C., Hansen K. C., Burlingame A. L., Trautman J. K., Shokat K. M., Adams C. L. (2005) PLoS Biol. 3, e128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]