Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are essential in T cell-mediated destruction of insulin-producing β cells in the islets of Langerhans in type 1 diabetes. In this study, we investigated T cell induction of intra-islet DC maturation during the progression of the disease in both autoimmune-prone NOD and resistant C57BL/6 mice. We demonstrated steady-state capture and retention of unprocessed β cell-derived proteins by semimature intra-islet DCs in both mouse strains. T cell-mediated intra-islet inflammation induced an increase in CD40 and CD80 expression and processing of captured Ag by resident DCs without inducing the expression of the p40 subunit of IL-12/23. Some of the CD40high intra-islet DCs up-regulated CCR7, and a small number of CD40high DCs bearing unprocessed islet Ags were detected in the pancreatic lymph nodes in mice with acute intra-islet inflammation, demonstrating that T cell-mediated tissue inflammation augments migration of mature resident DCs to draining lymph nodes. Our results identify an amplification loop during the progression of autoimmune diabetes, in which initial T cell infiltration leads to rapid maturation of intra-islet DCs, their migration to lymph nodes, and expanded priming of more autoreactive T cells. Therapeutic interventions that intercept this process may be effective at halting the progression of type 1 diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D)4 develops as a consequence of aberrant activation of immune cells targeting the β cells in the islet of Langerhans. In the NOD mouse model of T1D and in MHC-congenic C57BL/6 (B6)-IAg7 mice, initial priming for islet-reactive T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLNs) can be detected as early as 2 wk of age, and activated T cells are found in the islets shortly thereafter (1). However, diabetes onset appears in the NOD mice with much delayed kinetics, first emerging at 10 wk of age and reaching 60–80% by 40 wk among female mice. This slow progression of disease most likely reflects the time required to expand the islet-reactive T cell repertoire under the constant restraint of active immune regulation (2– 4). Understanding the mechanisms of subclinical disease progression may help to guide the design of new strategies for new therapeutic intervention.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a constituent of lymphoid organs and a variety of healthy peripheral tissues, including islets (5, 6). In steady state, DCs present self Ags to maintain T cell tolerance (7, 8). However, during infections, they acquire a more mature phenotype when they encounter microbial products and initiate a protective immune response. The involvement of DCs in autoimmune diabetes has been investigated in humans and animal models. They are found in insulitic lesions in patients with T1D (9). In NOD mice, DCs are among the first immune cells found in the islets (10, 11). As early as 14 days of age, DCs carrying islet Ags arrive in the PLNs and are capable of priming islet-autoreactive T cells (1). In older mice, depletion of DCs and macrophages using clodronate-loaded liposomes leads to clearance of established intra-islet infiltrates and prevents diabetes (12). More recently, NOD mice expressing diphtheria toxin receptor transgenes under the control of the CD11b or CD11c promoters were used to show that macrophage depletion had no impact on diabetes progression, whereas depletion of myeloid DCs prevented diabetes and depletion of plasmacytoid DCs exacerbated diabetes (13). Together, these studies demonstrate that DCs are critical to the initiation and progression of autoimmune diabetes.

To further dissect the mechanism by which DCs contribute to the development and progression of diabetes, we used mouse strains that express a β cell-specific GFP transgene under the control of the mouse insulin 1 promoter (MIP; referred to as MIP-GFP mice hereafter) (14, 15). The acquisition and processing of islet Ag by DCs can be visualized in these mice by tracking the GFP fluorescence. Previously, we observed a cohort of GFP-positive DCs in the PLNs of MIP-GFP mice, which formed stable conjugates with islet Ag-specific T cells, suggesting that these cells present tissue Ags during autoimmune insult of the islets (14, 15). In this study, we analyzed the steady-state and the T cell-mediated maturation of islet-resident DCs. We found that islet-resident DCs contained large amounts of unprocessed tissue Ags and exhibited a semimature phenotype in the steady state. The onset of T cell-mediated tissue inflammation induced islet-resident DCs to mature and migrate to draining lymph nodes (LNs). These results suggest that the interplay between T cells and DCs in the islets sustains and amplifies the immune response to tissue Ags, and thus contributes to the progression of autoimmune diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

B6.MIP-GFP (14) were backcrossed to the NOD strain, and mice between 9 and 15 generations onto the NOD background were used. B6 mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the CD11c promoter (16) (CD11c-YFP mice) were backcrossed to the NOD stain for more than 15 generations before intercrossing to generate NOD.Rag2−/−.CD11c-YFP mice. NOD.Yet40 mice were generated by backcrossing the B6.Yet40 mice (gift from R. Locksley, University of California, San Francisco, CA) (17) for more than 10 generations. These mice and NOD (The Jackson Laboratory and Taconic Farms), NOD.Rag2−/−, NOD.CD28−/−.MIP-GFP, B6.MIP-GFP.RIP-mOVA (rat insulin promoter-driven membrane-bound chicken OVA), NOD.BDC2.5 TCR transgenic, and B6.OT-I TCR transgenic mice were housed and bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of California Animal Barrier Facility. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of California approved all experiments.

Islet isolation

Islets were purified from mice using the standard collagenase protocols, as described previously (18). Briefly, mice were killed, and the pancreata were distended with 0.8 mg/ml collagenase P (Roche) solution via cannulated common bile duct. The distended pancreas was excised, incubated at 37°C for 17 min, and mechanically disrupted by gentle shaking. Pancreatic islets were purified by Histopaque-1119 (Sigma-Aldrich) density-gradient centrifugation and handpicked under a dissecting microscope.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

Mice were fasted overnight, and their baseline blood glucose was recorded. The mice were then challenged with an i.p. injection of a 20% glucose solution in normal saline, delivering a total of 2 g/kg body weight glucose. Blood glucose concentrations were recorded every 30 min over the next 120 min.

Enumerating DCs in intact islets

Handpicked islets from B6.CD11c-YFP mice were stained with Hoechst 33342 and allowed to settle onto a chambered coverslip slide (Invitrogen) before images were obtained on a Leica SP2 confocal microsope. YFP and Hoechst fluorescence signals were acquired simultaneously under ×20 oil objectives with 0.2- to 1.0-µm-thickness confocal sectioning. Islets from NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/− mice were stained with 5(and 6)-(((4-chloromethyl) benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine (CMTMR; Invitrogen), embedded in Matrigel (BD Bioscience), and immobilized on a coverslip. YFP and CMTMR fluorescent signals were acquired simultaneously on a custom-built two-photon microscope using a water immersion ×20 objective and 3- to 4-µm step in z direction. Postacquisition three-dimensional reconstruction and data analyses were performed using Imaris (Bitplane) and Metamorph (Universal Imaging) software.

Flow cytometry

Handpicked islets were dissociated by incubating with a nonenzymatic solution (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by trituration per the manufacturer’s instructions. LN cells were made into a single-cell suspension by collagenase D digestion, as described for islet cells. The following Abs were used to stain the cells: allophycocyanin-Cy7-labeled anti-CD45, PE-Cy7-labeled anti-CD11c (clone N418), PE-labeled anti-CD40 (clone 3/23), biotinylated anti-CD80, allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD86 (all eBioscience), Alexa 700-labeled anti-IAg7 for NOD cells, and Alexa 700-labeled anti- MHC class II (clone N22) for B6 cells. The cells were washed and then labeled with Quantumdot 605-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen). Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star).

Cell transfers

FACS-purified CD4+CD62LhighCD25− cells from NOD.BDC2.5.Thy1.1 TCR transgenic mice were expanded with anti-CD3- and anti-CD28-coated beads for 10 days and transferred to NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− recipients via i.p. injection (0.5 × 106/mouse). CD8+ T cells were enriched from OT-I LN and spleen cells using the CD8 StemSep negative selection kit (StemCell Technologies), and 5 × 106 CD8+ cells/mouse were transferred into B6.MIP-GFP.RIP-mOVA recipients by i.v. injection.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Pancreatic islets in NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice and their transgene-negative littermates were analyzed histologically, as described before (19). Briefly, 5-µm paraffin sections were stained with a mixture of rabbit anti-glucogon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide to identify α, δ, and polypeptide-producing cells, respectively. The stain was developed using HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary Abs, followed by the chromagenic substrate 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine. β cells in the islets were then identified by aldehyde fuchsin strain, followed by H&E counterstains.

Radiation bone marrow chimera

NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− or NOD.Rag2−/− received 1300 rad of total body radiation in two doses ~20 h apart (850 and 450 rad) and were reconstituted with 5–6 × 106 bone marrow cells from NOD.Rag2−/− or NOD.MIP-GFP mice, respectively. Phenotypes of intra-islet DCs were analyzed 12 wk after the bone marrow reconstitution.

Fluorescent confocal microscopy

Islet cells were isolated from NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice and fixed with 0.5% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 5 min. The cells were stained with anti-CD11c biotin (clone HL-3), followed by streptavidin QDot 605. The cells were resuspended in PBS with 0.25% low-melting agarose and transferred to a chamber slide for imaging. Confocal imaging was done using a modified Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S microscope equipped with a spinning-disk confocal scanner (Yokogawa) with a ×100/1.4 NA oil immersion objective and an iXon EMCCD camera from Andor. Postacquisition analyses were performed using Metamorph software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done with the aid of Prism software (GraphPad) using the tests indicated.

Results

Phenotype of NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice

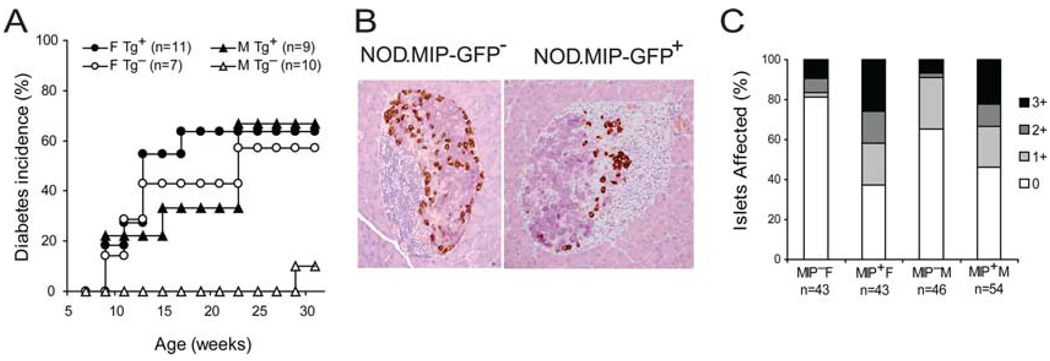

To investigate the uptake and processing of autoantigens during T1D progression, we used the MIP-GFP mice, which express GFP as a model islet Ag exclusively in the pancreatic β cells and not in other organs, particularly the thymus (14). We backcrossed MIP-GFP transgenic mice from the B6 background to the NOD background to perform comparative analyses in the autoimmune-resistant B6 and susceptible NOD strains. Diabetes was evident after three rounds of backcrosses. After nine generations of backcrossing, the rate of diabetes progression in female MIP-GFP transgenic mice was similar to that of their transgene-negative littermates (Fig. 1A) and standard NOD mice purchased from commercial sources and housed in the same facility (data not shown). Diabetes incidence was higher in male MIP-GFP transgenic mice than in their transgene-negative littermates (Fig. 1A). A previously published NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mouse line generated at The Jackson Laboratory by directly injecting the MIP-GFP transgene into NOD embryonic stem cells developed diabetes without insulitis (20). In that model, diabetes development was most likely a consequence of β cell toxicity due to overexpression of the transgene. Thus, we collaborated with The Jackson Laboratory and performed histological examination of the pancreata from our backcrossed NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice. The results showed that the islets in male and female prediabetic NOD. MIP-GFP pancreata displayed widespread intra-islet infiltrations, typical of that observed in standard NOD mice in The Jackson Laboratory (Fig. 1B). The severity of insulitis in these mice was similar to that in their transgene-negative littermates (Fig. 1C). These analyses demonstrate that this backcrossed NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic line shows typical signs of autoimmune diabetes in both males and females. Thus, both male and female NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice were used in the rest of this study.

FIGURE 1.

Phenotype of NOD.MIP-GFP mice. B6.MIP-GFP transgenic mice were backcrossed to the NOD background. A, Diabetes incidence of NOD.MIP-GFP mice and their transgene-negative littermates at nine generations of backcrossing are shown. B, Immunohistological analysis of islets in NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice and in transgene-negative littermates at eight generations of backcrossing. The β cells are stained deep purple by aldehyde fuchsin staining. The β, δ, and polypeptide-producing cells are identified by the brown immunohistochemical staining for glucogon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide, respectively. C, Insulitis score of NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice and their transgene-negative littermates at 9–15 wk of age. Numbers of islets analyzed are shown in the category x-axis label.

To determine the phenotype of intra-islet DCs in B6 and compare it with that of genetically predisposed NOD mice in the absence of inflammation, it was necessary to further intercross NOD.MIP-GFP mice to NOD.Rag2−/− mice to produce NOD. MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice. This allowed us to analyze islet DCs in the absence of autoimmune response in steady state in both strain backgrounds. The NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice never developed diabetes, although their glucose tolerance was somewhat compromised (supplemental Fig. 1A),5 whereas the parental B6.MIP-GFP mice showed no apparent increase in glucose intolerance, as reported previously (14) (supplemental Fig. 1B).5

Phenotype of intra-islet DCs in healthy islets

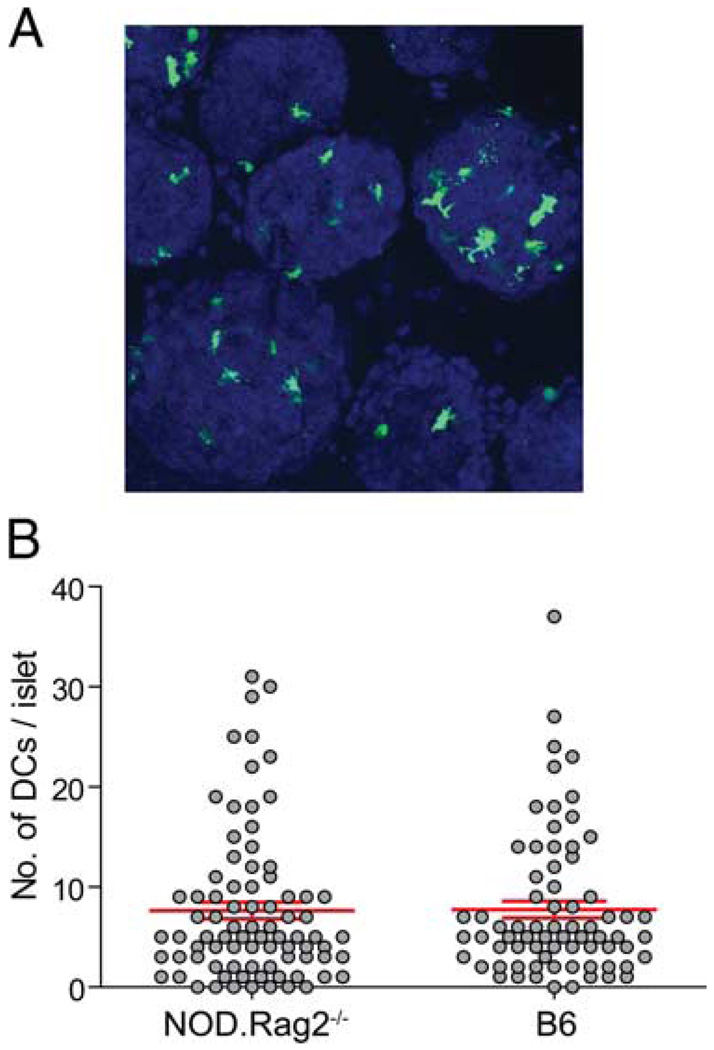

As in most peripheral tissues, islets contain resident DCs, which are important in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes and allogeneic islet transplantation rejections (21). To compare the numbers of DCs in healthy islets in steady state in the NOD.Rag2−/− and B6 mice, we isolated islets from NOD.Rag2−/− and B6 mice that express a YFP under the control of the CD11c promoter (16). In these mice, DCs were marked by YFP and could be visualized by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 2A). The numbers of DCs in individual islets ranged from 0 to 37, with an average of 7.75 DCs/ islet in a normal B6 mouse (Fig. 2B). The numbers of DCs in each healthy islet in NOD.Rag2−/− mice ranged from 0 to 31 with an average of 7.65 (Fig. 2B), similar to that observed in B6 mice.

FIGURE 2.

Location and numbers of intraislet DCs. Islets were isolated from NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/− and B6.CD11c-YFP mice, stained with CMTMR or Hoechst 33342, and analyzed by microscopy. A, Maximal z projection of a representative objective field of B6.CD11c-YFP islet imaged. B, Enumeration of numbers of DCs in islets. Each circle represents one islet, and the lines represent mean ± SD (NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/−, n = 82, mean = 7.65, SD = 7.51; B6.CD11c-YFP, n = 72, mean = 7.75, SD = 7.18).

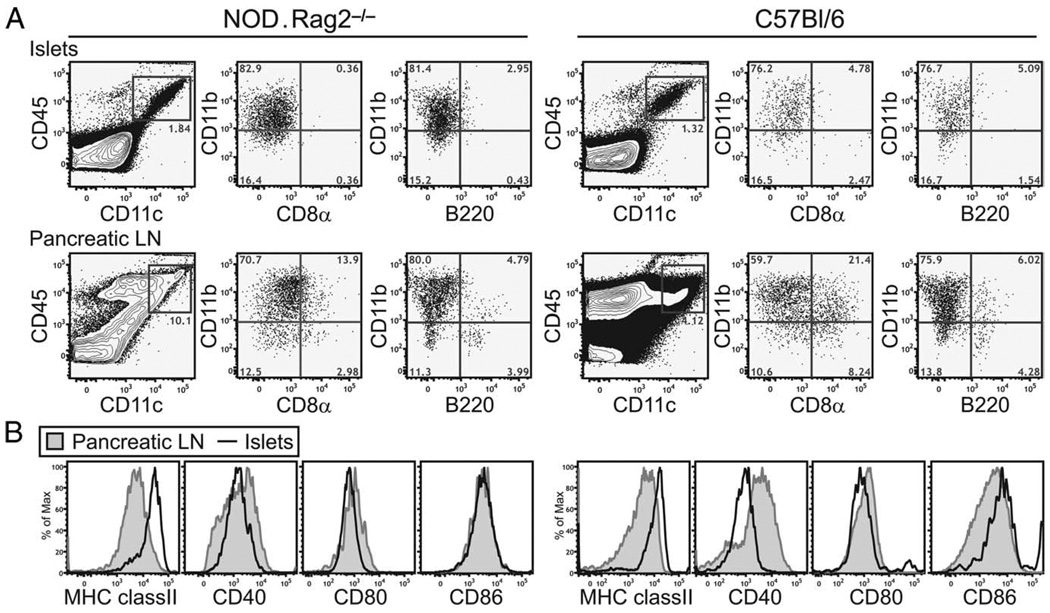

Flow cytometry analysis revealed that most of the CD45+ leukocytes in the islets in B6 and NOD.Rag2−/− mice were CD11c+ DCs. These cells were virtually all CD11b+ CD8α−, B220− (Fig. 3A), and PDCA-1− (data not shown). Intra-islet DCs in both strains showed a semimature phenotype with minor variations in the expression levels of activation markers. They uniformly expressed high levels of cell surface MHC class II when compared with their counterparts in the PLNs (Fig. 3B). In addition, they also expressed intermediate to high levels of CD86, intermediate amounts of CD40, and low levels of CD80 (Fig. 3B). Because DCs in immunodeficient hosts such as Rag2−/− mice have documented developmental defects, we also compared intra-islet DCs in 3- to 4-wk-old NOD and B6 mice before the onset of intra-islet T cell infiltrations. Similar to that observed in the NOD.Rag2−/− and older B6 mice, intra-islet DCs in young NOD and B6 mice were CD11b+CD8α−B220− and expressed higher levels of MHC class II and lower amounts of CD40 when compared with their counterparts in the pancreatic LNs (supplementary Fig. 2).5 Thus, the expression of this semimature phenotype in B6 and NOD.Rag2−/− mice suggested that the phenotype was not specific to the NOD autoimmune background or dependent on an autoimmune response.

FIGURE 3.

Phenotype of intra-islet DCs in steady state. Single-cell suspension of islets and PLNs isolated from NOD.Rag2−/− or B6 mice were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the cell surface markers expressed by intra-islet DCs. A, Characterization of subtypes of intra-islet DCs. Events shown are gated on live cells (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)−). B, Expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules expressed on intra-islet DCs (gated on CD45+DAPI−CD11c+ cells, bold lines) in comparison with DCs in the PLN (shaded histograms). The result is representative of at least two independent experiments in each of the mouse strains.

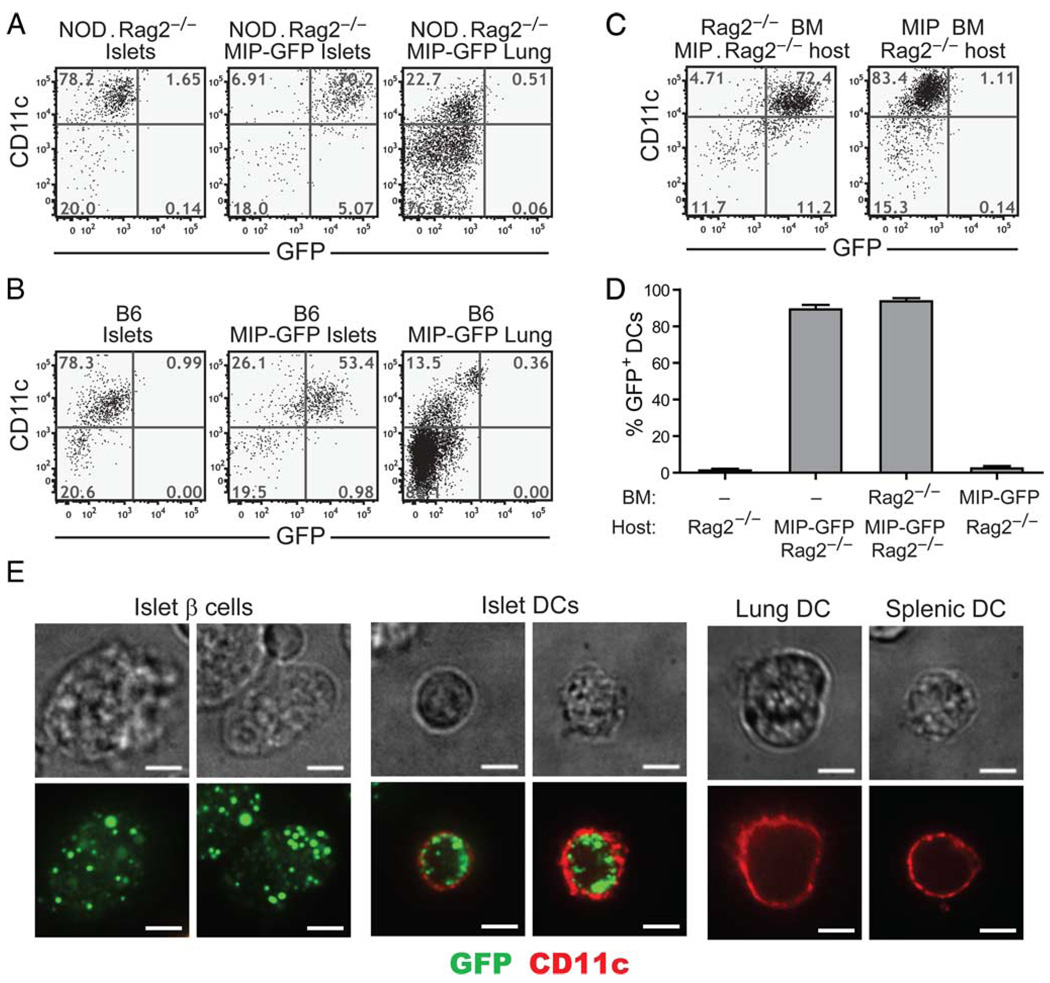

To assess the steady-state uptake of islet Ags by intra-islet DCs, we took advantage of the MIP-GFP mice. In these mice, GFP is selectively expressed in the β cells, and therefore serves as a model self Ag. Its uptake and processing by islet-resident DCs can be monitored by examining the levels of green fluorescence in the DCs using flow cytometry and microscopy. Strikingly, nearly 100% of the intra-islet DCs in the NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice contained green fluorescent signal, suggesting that all the intraislet DCs had taken up β cell Ag (Fig. 4A). In contrast, none of the splenic DCs were GFP+ (data not shown), nor were other tissue-resident DCs, such as those from lungs (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the majority of DCs in the islets of B6.MIP-GFP mice were GFP+ (Fig. 4B). Expression of GFP by intra-islet DCs was also observed in young NOD.MIP-GFP transgenic mice before the onset of insulitis (supplementary Fig. 3).5

FIGURE 4.

Intra-islet DCs in MIP-GFP transgenic mice acquire and maintain intact GFP. Flow cytometric analysis of GFP expression by intra-islet and lung DCs in NOD.Rag2−/−.MIP-GFP (A) and B6.MIP-GFP (B) mice. Events shown are gated on CD45+DAPI− cells. The result is a representative of at least two independent experiments. C, Sample flow cytometric profile of GFP signal in intra-islet DCs in radiation bone marrow chimeras is shown. The donor-recipient combinations are indicated on top of each plot. D, Summary of the frequencies of GFP+ cells in DC gate (CD45+DAPI−CD11c+ cells) in NOD.Rag2−/− (n = 4), NOD.Rag2−/−.MIP-GFP (n = 7), NOD.Rag2−/− into NOD.Rag2−/−.MIP-GFP chimeras (n = 4), and NOD.MIP-GFP into NOD.Rag2−/− chimeras (n = 6). Error bars represent SDs. E, Confocal microscopic analysis of GFP in intra-islet, lung, and splenic DCs in NOD. Rag2−/−.MIP-GFP transgenic mice. Islets and lung cells were dissociated and stained for CD11c (red). The presence of GFP (green) in CD11c (red)-expressing cells was examined by confocal microscopy (original magnification = ×100, scale bar = 5 µm). Fluorescent images show a single medial Z-plane. Phase-contrast images are shown on top for reference. The result is a representative of five independent experiments.

Next, we generated radiation bone marrow chimeras to determine whether the presence of the GFP in intra-islet DCs was due to leaky expression of the transgene in islet DCs. NOD. MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with bone marrow from NOD.Rag2−/− donors. The radiation eliminated over 98% host intra-islet DCs by 19 days after the treatment (data not shown). Nearly all of the intra-islet DCs in every chimeric mouse were GFP+, a finding similar to that observed in the NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice. In contrast, all the intra-islet DCs in the MIP-GFP transgene-negative recipients of MIP-GFP transgene+ bone marrow cells were GFP− (Fig. 4, C and D). These results demonstrated that intra-islet DCs did not have to carry the MIP-GFP transgene to become GFP+. Thus, the GFP signal detected in the intra-islet DCs of the MIP-GFP transgenic mice was due to islet-Ag uptake rather than aberrant expression of the MIP-GFP transgene by the islet DCs.

We further confirmed that the GFP was found inside DCs by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4E). The punctate, apparently vesicular pattern of the GFP inside the DCs suggests that the DCs phagocytosed GFP from the surrounding β cells. Because the GFP inside the DCs remained fluorescent, at least some of the internalized GFP was not degraded by the DC’s Ag-processing machinery and retained a tertiary structure to allow fluorescent emission. Thus, in steady state, intra-islet DCs on both the NOD and B6 backgrounds displayed a semimature phenotype and uniformly contained unprocessed β cell-specific Ags.

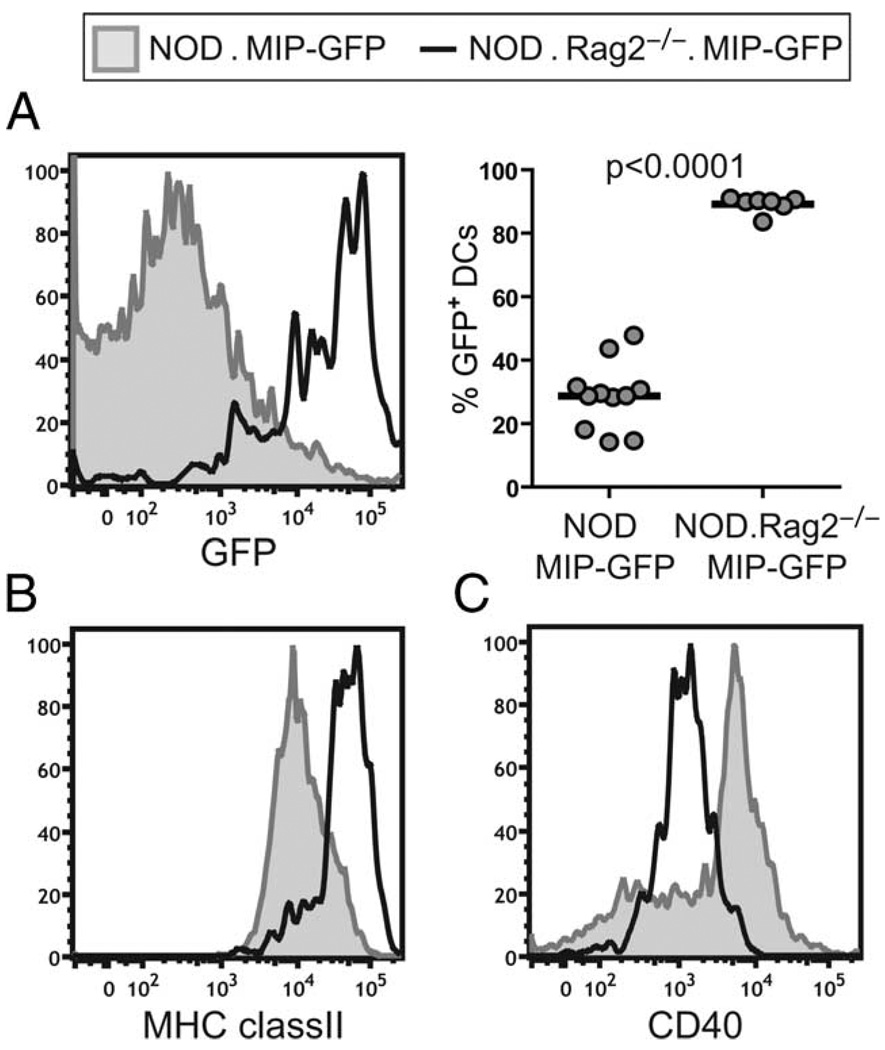

Inflammation induces intra-islet DC maturation

In analyzing the basal level of GFP fluorescence in the intra-islet DCs of MIP-GFP mice on various backgrounds, we noticed that the phenotype of the DCs in the islets of prediabetic NOD.MIP-GFP mice was strikingly different from that in NOD.MIP-GFP. Rag2−/− and B6.MIP-GFP mice. The GFP fluorescence was significantly reduced in the DCs in inflamed islets of NOD.MIP-GFP, so that less than half of the DCs were GFP+ (Fig. 5A). The DCs showed slightly reduced MHC class II expression (Fig. 5B), and CD86 expression remained high (data not shown). Moreover, a subpopulation of intra-islet DCs in the NOD mice expressed higher amounts of CD40 (Fig. 5C) and CD80 (data not shown) as compared with the DCs in NOD.Rag2−/− mice. Given the association of CD40 up-regulation with DC maturation (22), we hypothesized that this change in phenotype was a result of DC maturation induced by the inflammatory infiltrate in the islets.

FIGURE 5.

Phenotype of intra-islet DCs in NOD.MIP-GFP mice. Single-cell suspension of islets isolated from NOD.MIP-GFP or NOD.MIP-GFP. Rag2−/− was analyzed by flow cytometry. Histogram overlays of GFP fluorescence (A, left) and cell surface expression of MHC class II (B), and CD40 (C) in NOD.MIP-GFP (shaded histograms) vs NOD.MIP-GFP. Rag2−/− (bold lines) are shown. A summary chart of percentages of GFP+ cell DC gate (CD45+DAPI−CD11c+) in the islets of NOD.MIP-GFP (n = 11) and NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− (n = 7) mice is shown (A, right). The p value was obtained using unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction.

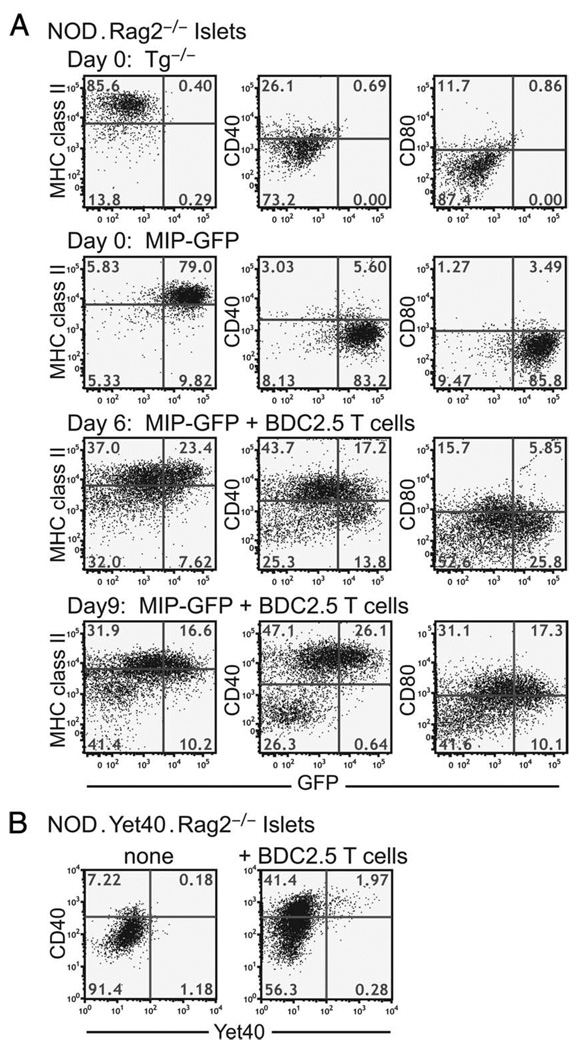

To test this hypothesis, we induced T cell-mediated intra-islet inflammation in the NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25− T cells isolated from the NOD.BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. This protocol induces diabetes synchronously in all mice between 10 and 14 days after cell transfer. We isolated islets and examined the phenotype of the DCs on days 6 and 9 after cell transfer. On day 6, intra-islet DCs had up-regulated CD40 and CD80 and showed reduced GFP fluorescence as compared with the phenotype of control mice that did not receive T cells (Fig. 6). The CD40high DCs showed greater loss of GFP fluorescence, which suggested that the diminution of GFP fluorescence resulted from loss of GFP structural integrity due to enhanced Ag processing and/or reduced Ag uptake in more mature DCs. The expression levels of MHC class II decreased slightly, and those of CD86 remained unchanged relative to the mice that did not receive T cells (data not shown). By day 9 after cell transfer, the CD40mid GFP+ DC population characteristic of noninflamed islets had been completely replaced by two distinct populations of DCs. In one population, the DCs were almost all CD40high, showed reduced GFP fluorescence, and increased CD80 expression. The second population of DCs displayed a MHC class IIlow, GFP−, CD40−, and CD80− immature phenotype, and are likely to be recent immigrants into the islets (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Kinetic changes in DCs in inflamed islets. A, NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice received CD4+CD25− cells from BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. GFP fluorescence and cell surface expression of MHC class II, CD40, and CD80 on intra-islet DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry on days 6 and 9 after cell transfer. Examples of a NOD.Rag2−/− and a NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mouse without T cell transfer are shown for comparison. This result is representative of at least five independent experiments. B, NOD.Yet40.Rag2−/− mice received CD4+CD25− cells from BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. On day 8 postcell transfer, the presence of YFP signal among intra-islet DCs was assessed by flow cytometry. An age-matched untreated NOD.Yet40. Rag2−/− sample is shown for comparison. This result represents two independent experiments. Events shown are gated on CD45+DAPI−CD11c+ cells in islets.

Our data to date demonstrate that T cell-mediated inflammation in the islets in the NOD mice led to enhanced Ag processing and up-regulation of costimulatory molecules by intra-islet DCs. DC maturation is often accompanied by production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-12 (23, 24). We analyzed the expression of the p40 chain of IL-12 and IL-23 in our model to determine whether the expression of these two cytokines was regulated by the intraislet inflammation. We crossed the p40 reporter mouse, Yet40 (17), 15 generations onto the NOD background, and then further intercrossed to make the NOD.Yet40.Rag2−/− mice. The intra-islet DCs in these mice did not express YFP, demonstrating that there was no constitutive production of IL-12 or IL-23 (Fig. 6B). On days 9–10 after BDC2.5 CD4+CD25− cell transfer, the islets had massive T cell infiltration and the mice were on the brink of developing diabetes. As observed before, the intra-islet DCs up-regulated CD40 expression; however, there was no significant increase in YFP+ DCs in these inflamed islets (Fig. 6B). Consistent with this result, we observed very few YFP+ DCs in the inflamed islets of prediabetic NOD.Yet40 mice (data not shown), much lower in frequency than the CD40highGFPlow mature DCs in the islets of prediabetic NOD.MIP-GFP mice (Fig. 5). Thus, most mature DCs in inflamed islets did not express p40, and consequently had no IL-12 and IL-23 expression.

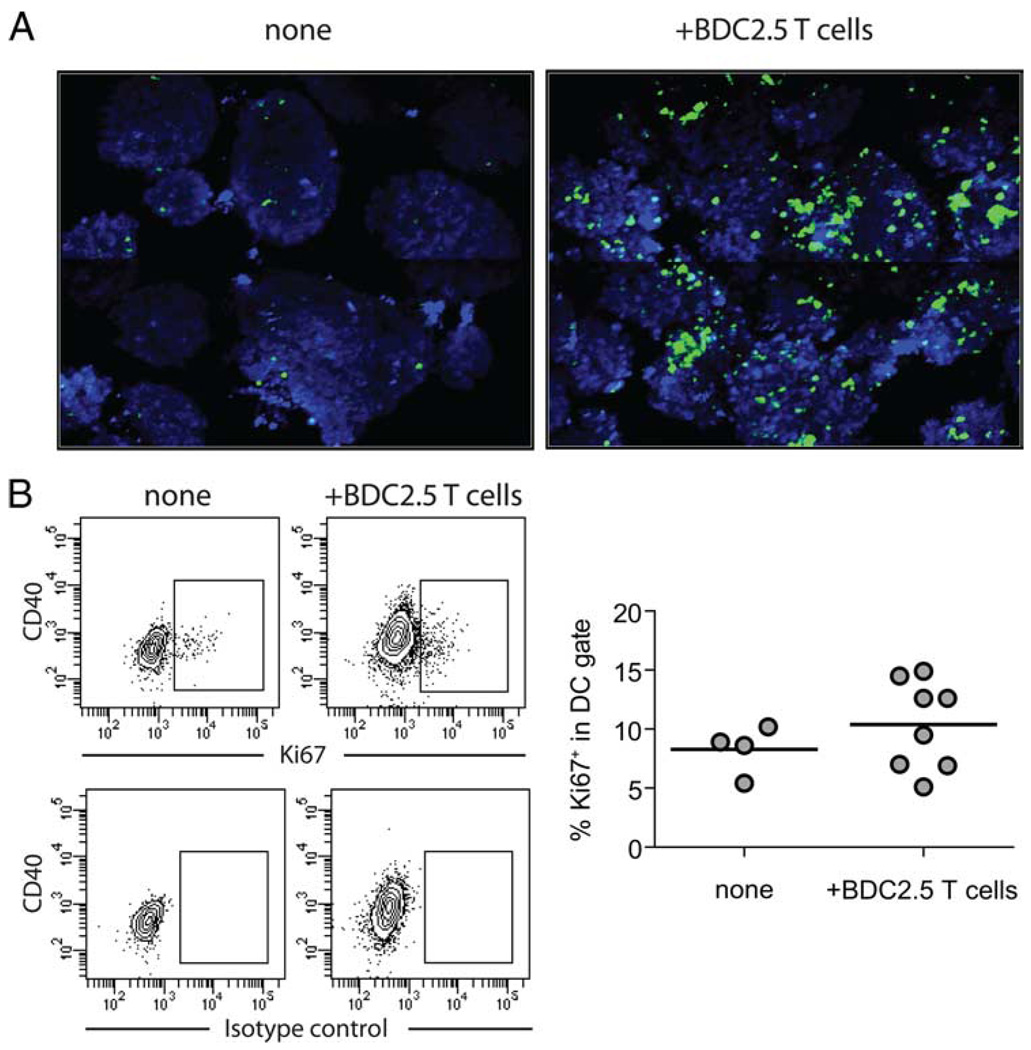

While analyzing DCs from steady-state and inflamed islets, we noticed higher recovery of DCs from inflamed islets. To determine whether islet inflammation led to an increase in DC numbers, we imaged islets isolated from NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/− mice 8 days after transferring CD4+CD25− T cells from BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. We observed a marked increase in the YFP fluorescence signal in the inflamed islets when compared with non-inflamed islets isolated from NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/− mice (Fig. 7A). DCs in the inflamed islets formed large aggregates, making it difficult to accurately assess the numbers of DCs in each islet. Therefore, we measured the total volume of YFP signal and volume of islet tissue imaged to estimate the fold increase of DCs in the same amount of islet tissue. In uninflamed islets, DCs represented 0.88% of islet tissue, by comparison, in inflamed islets, DCs represented 10.97% of the islet tissue. Thus, at this late stage of islet destruction, there was over 12-fold increase in DC numbers in the islets.

FIGURE 7.

Increase of DC numbers in inflamed islets. A, Islets were isolated from untreated NOD.CD11c-YFP.Rag2−/− mice (left) or from similar mice 8 days after transferring CD4+CD25− cells from BDC.2.5 TCR transgenic mice (right) were counterstained with CMTMR (shown in blue) and imaged on a two-photon microscope. The images are collages of consecutive objective fields representing imaging volume of 780 × 618 × 176 µm3 for untreated islets (left) and 780 × 618 × 222 µm3 for inflamed islets (right). B, Islets were isolated from untreated NOD.Rag2−/− mice and similar mice 6–7 days after receiving CD4+ CD25− cells from BDC2.5 TCR transgenic mice. Expression of Ki67 by intra-islet DCs was analyzed by flow cytometry. Sample contour plots of anti-Ki67 staining and isotype control Ab staining patterns are shown, and a chart summarizing results from two independent experiments is shown below. Events shown are gated on CD45+ CD11c+ cells. Each circle represents one islet, and the lines represent mean of the group.

To determine whether this increase was due to local expansion of DCs, we assessed the frequency of DCs that express the mitosis marker Ki67. In steady state, an average of 8% intra-islet DCs were Ki67+, indicating that they are actively proliferating (Fig. 7B). T cell infiltration led to a mild increase in the average percentage of DCs expressing Ki67; however, the small rise could not account for the massive increase in DCs in the islets. Thus, T cell infiltration in the islets induced a dramatic increase in intra-islet DC counts, which is mostly due to recruitment from circulation.

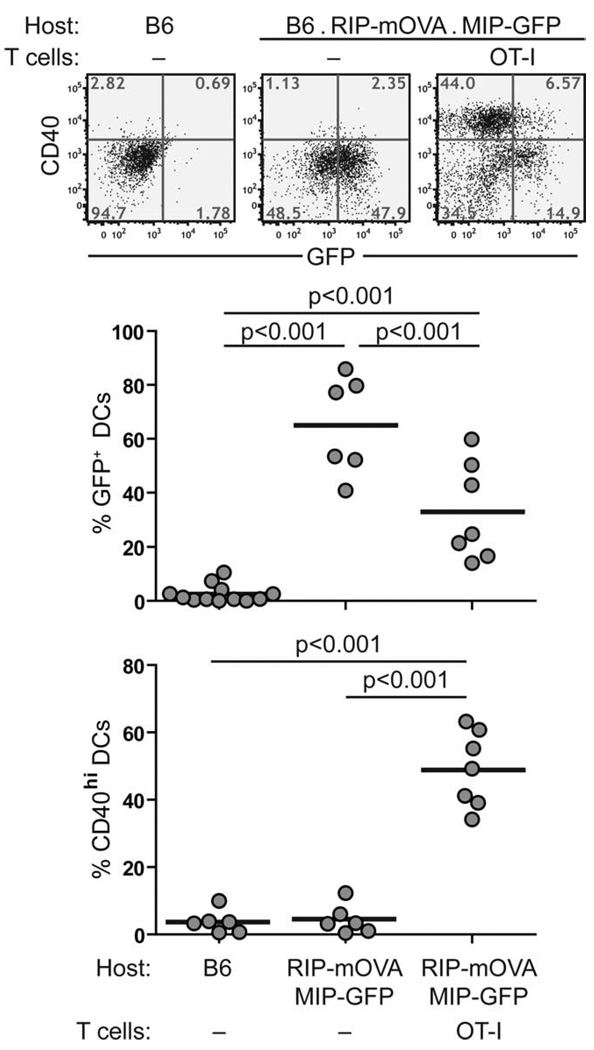

To similarly investigate DC phenotype in inflamed islets on the B6 background, we crossed the B6.MIP-GFP mice to the RIP-mOVA mice so that the double-transgenic mice expressed both GFP and chicken OVA in the β cells. T cell-mediated inflammation was induced in these RIP-mOVA.MIP-GFP mice by adoptive transfer of CD8 cells from OT-I TCR transgenic mice. This protocol typically induces diabetes 1 wk after cell transfer (25). Similarly to what we observed on the NOD background, intra-islet DCs up-regulated CD40 and CD80 (data not shown) and showed reduced GFP fluorescence 5 days after OT-I T cell transfer (Fig. 8). Taken together, in both experimental models, we found that intra-islet inflammation induced maturation of islet-resident DCs, which was evident from the increased CD40 and CD80 expression and a reduction in the amounts of intact β cell Ags, most likely through enhanced Ag processing.

FIGURE 8.

Phenotypic changes in intra-islet DCs in B6.MIP-GFP.RIP-mOVA mice after inflammation was induced. B6.MIP-GFP.RIP-mOVA mice received CD8+ cells from OT-I TCR transgenic mice. GFP fluorescent and cell surface expression of CD40 on intra-islet DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 5 after cell transfer and compared with those from untreated B6 and B6.MIP-GFP.RIP-mOVA mice. Representative dot plots are shown on top, and a summary of all mice analyzed is shown in the chart on the bottom. Values of p were obtained using a one-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s post-test. The result represents four independent experiments.

Migration of mature intra-islet DCs to PLNs

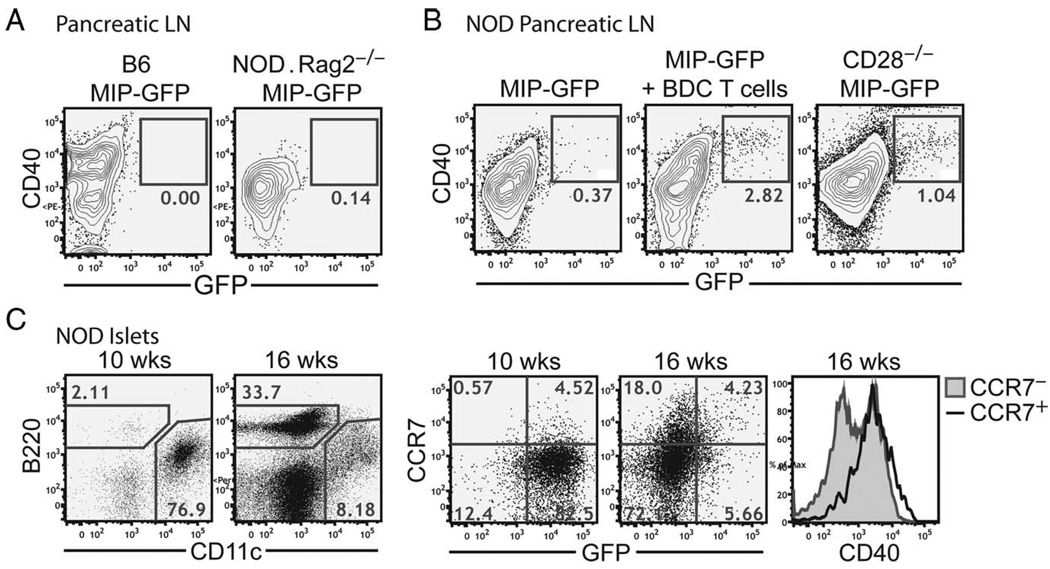

We previously detected 20 –300 GFP+ DCs in the PLNs, which represents 0.3–10% of the total DCs in the PLNs of the MIP-GFP mice on a mixed B6 and NOD background (15). The fact that these DCs carried endogenous islet Ags was also apparent in this background because islet Ag-reactive T cells formed stable contacts with these DCs. By comparison, under noninflammatory conditions, the number of GFP+ DCs in the NOD. MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− mice and the B6.MIP-GFP mice was below the detection limit of 0.2% in the PLNs (Fig. 9A). Taken together with our previous findings, these results suggest that the presence of GFP+ DCs in the draining LNs depends on intraislet inflammation.

FIGURE 9.

Migration of intra-islet DCs to the PLNs. A, Flow cytometric analysis of GFP signal in DCs in the PLNs of B6.MIP-GFP (left) or NOD.MIP-GFP.Rag2−/− (right) mice. Events shown are gated on CD45+DAPI−CD11c+ cells. B, Flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ DCs in the PLNs of NOD.MIP-GFP mice (left), NOD.MIP-GFP mice 5 days after injection of activated CD4+CD25− cells from BDC.2.5 TCR transgenic mice (middle), and 7-wk-old NOD.MIP-GFP.CD28−/− mice (right). Results are representative of at least two independent experiments. C, Flow cytometric analysis of CCR7 expression on intra-islet DCs in prediabetic NOD.MIP-GFP mice. Contour plots show lymphocytic infiltration into the islets of representative early prediabetic mice (10 wk) vs late prediabetic mice (16 wk), and are gated on CD45+DAPI− cells. The histogram overlay (top) shows CCR7 expression in the CD45+DAPI−CD11c+ population from the early vs late prediabetic islets. Histogram overlays (below) show GFP fluorescence and CD40 expression in the CCR7+ vs CCR7− populations of intra-islet DCs from late prediabetic mice.

Surprisingly, GFP+ DCs barely reached over 0.2% in the PLNs of prediabetic fully backcrossed NOD.MIP-GFP (Fig. 9B, left panel). This result contrasted with previous observations in earlier backcrosses of NOD.MIP-GFP mice, which were made after three to five backcrosses from the B6 to NOD background (15). In these early backcrosses, 70% of the male and female MIP-GFP transgene-positive mice abruptly developed diabetes between 11 and 12 wk of age, reaching 100% by 15 wk (data not shown). Thus, we hypothesized that rapid and synchronized islet inflammation and β cell destruction might promote DC maturation and increase the magnitude of islet DC migration into the PLNs.

We tested this hypothesis using two approaches to induce synchronous islet inflammation. The first approach used a modified BDC2.5 T cell adoptive transfer protocol that induces rapid onset of diabetes by 7–10 days in 100% of prediabetic NOD mice (26, 27). Transferring preactivated BDC2.5 T cells to NOD.MIP-GFP mice induced the appearance of GFP+ DCs 5 days later in the PLNs; these DCs resided exclusively among the CD40high populations (Fig. 9B, middle panel). The second protocol used the NOD.CD28−/− mice that developed diabetes synchronously at 10–12 wk due to their deficiency in regulatory T cells (28). In these mice, GFP+ DCs were readily detected at 7–8 wk of age in the PLNs (Fig. 9B). Thus, rapid, synchronous, and pathogenic responses appear to drive DCs to the LN carrying an increased cargo of unprocessed Ags.

Finally, DC migration to LNs requires the expression of CCR7, the receptor for LN homing chemokine, CCL21. Thus, we analyzed CCR7 expression on the intra-islet DCs of prediabetic NOD.MIP-GFP mice and found that CCR7 expression was induced on both GFP+ and GFP− DCs in inflamed islets (Fig. 9C). Both GFP+ and GFP− CCR7+ DCs were more mature with higher level of CD40 expression (Fig. 9C). Together, these results suggested that CD40high DCs had the capacity to enter the PLNs regardless of whether the ingested tissue Ag had been fully processed or not.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed phenotypic changes of islet-resident DCs during the progression of T1D using the MIP-GFP reporter mice in both autoimmune-prone and resistant backgrounds. GFP has a unique tertiary structure that makes it resistant to chemical and physical denaturation (29 –31). However, under low pH conditions, such as those found in late endosomes and lysosomes of mature DCs, GFP becomes susceptible to proteolysis and quickly loses its ability to fluoresce (32, 33). These properties of GFP allowed us to visualize and quantitate Ag uptake and processing in live DCs during tissue Ag cross-presentation. Our results demonstrate that intra-islet DCs exhibit a semimature phenotype in steady state and ingest large amounts of tissue Ags, which can remain unprocessed. Upon induction of tissue inflammation, DCs begin to process Ag, acquire a more mature phenotype, and migrate to the PLNs to amplify the ongoing immune response. These results extend the current understanding of the role of DCs in diabetes pathogenesis and suggest that the DCs provide a positive feedback mechanism in amplifying autoimmune responses against islet Ags. This mechanism represents a normal physiological process of an immune response and not a peculiarity of the autoimmune-prone NOD mice because it was similarly observed in the nonautoimmune B6 mice. Thus, the positive feedback loop per se is not sufficient to confer diabetes susceptibility, but it may enhance the pathogenic anti-β cell responses initiated by defects in thymic selection and peripheral regulation in the NOD mice (34).

In steady state, tissue-dwelling DCs migrate to the draining LNs where they present self Ags in a process that is thought to contribute to the maintenance of self tolerance (8). DCs resident in the peripheral tissue are thought to exhibit an immature phenotype with low cell surface expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules and high endocytic capacities, as that observed in Langerhans cells and cultured bone marrow-derived DCs. In contrast, tissue-derived migratory DCs in LNs express higher amounts of MHC and costimulatory molecules on their cell surface, suggesting that only mature DCs gain capacity to enter draining LNs (35). We found that intra-islet DCs displayed a phenotype distinct from the previously reported immature or mature DCs with high levels of MHC class II and CD86, intermediate levels of CD40, and little CD80 expression. The expressions of MHC class II and CD86 were not further enhanced by inflammatory stimulations, suggesting that they were expressed at the same level as in fully matured DCs. However, their relatively low expression of CD40 and CD80 suggests that they are distinct from fully mature DCs.

The most distinguishing feature of the intra-islet DCs was that they uniformly contained large amounts of unprocessed β cell Ags, as visualized by their bright GFP signals in the MIP-GFP transgenic mice. Previously published electron microscopic analyses have demonstrated that MHC class II Ag-positive cells in islets contained granule-like structures that are recognized by Abs to insulin (6, 36). This result suggests that intra-islet DCs contain intact Ags taken up from β cells, consistent with our finding with the MIP-GFP reporters. Immature DCs have been shown to maintain Ag in its unprocessed form and begin processing upon receiving a maturation signal, such as LPS (37). DCs containing unprocessed proteins have also been observed in vivo and are generally found to be present at very low frequencies (38, 39). The maintenance of large amounts of unprocessed Ags may also be a physiological correlate of maintenance of protein aggregates within specific compartments in DCs (40). Our observation extends these previous findings to demonstrate that virtually all tissue-dwelling DCs stably maintain unprocessed protein in the absence of inflammatory signals. Because the tertiary structure of GFP and its ability to fluoresce are very sensitive to low pH environment, our results suggest that the endocytosed tissue Ags are maintained in a pH neutral environment, such as early endosomes, and maturation stimuli induced their transition to an acidic compartment for processing and presentation.

A previous study elegantly demonstrated in the B6.RIP-mOVA model that DCs constitutively migrate from tissues to present tissue- specific Ags in the draining LNs in the absence of overinflammatory stimulations (41). Once reaching the LNs, migratory DCs are short-lived; thus, they need to be continuously replenished from the tissue. In this study, we observed that virtually all DCs in the islets contained intact tissue Ags, whereas DCs bearing intact tissue Ags were very rare in the draining LNs of the same animal. This result suggests that processing of acquired tissue Ags normally precedes the migration of the DCs to the draining LNs. However, this coordinated process became deregulated under extreme inflammatory conditions, such as those observed in earlier backcrosses of NOD.MIP-GFP mice, in fully backcrossed NOD. MIP-GFP.CD28KO, and fully backcrossed NOD.MIP-GFP receiving a large dose of activated diabetogenic T cells. This deregulation allowed a few of the islet-derived DCs to reach the LN before the complete processing of acquired GFP and other islet Ags. It should be noted that these GFP+ DCs only represented a fraction of islet Ag-bearing DCs in the pancreatic LN because many islet-derived DCs fully process the acquired Ag, thus losing GFP fluoresce before arriving in the pancreatic LN.

A recent study directly examined the steady-state presentation of another islet model Ag, hen egg lysozyme, which was driven by a transgenic insulin promoter (6). In that system, up to 90% of intra-islet DCs and 50% of PLN DCs expressed processed hen egg lysozyme peptide-MHC complex on the cell surface. Our use of GFP model Ag in this study showed that unprocessed Ags were present in nearly all intra-islet DCs in steady state. These results together suggest that, in the absence of inflammation, intra-islet DCs have a limited capacity to process and present acquired Ag, allowing them to display processed Ags on the cell surface while retaining unprocessed Ag intracellularly. The absence of DCs with intact Ag in the draining LN suggests that a fraction of islet-resident DCs must degrade all acquired tissue Ags before migrating to LNs. This steady-state activity is enhanced by intra-islet inflammation leading to DC maturation, loss of unprocessed Ag in majority of the DCs, and enhanced migration to PLNs.

In contrast to DCs matured by TLR ligands, the mature DCs we observed in inflamed islets did not express inflammatory cytokines; thus, phenotypically they resembled DCs activated by inflammatory cytokines and mechanical disruptions (42, 43). These previous studies suggest that such alternatively activated DCs are tolerogenic because they fail to elicit IFN-γ production, but promoted IL-10 secretion from T cells. It is important to point out that these studies were conducted with bone marrow-derived or secondary lymphoid tissue-resident DCs that are likely distinct from peripheral tissue-resident DCs in their maturation status and functional capacities (35). In our models, maturation of islet-resident DCs was clearly associated with T cell activation and tissue destruction. Furthermore, DCs isolated from inflamed islets in NOD mice were sufficient to induce T cell proliferation and secretion of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α ex vivo (K. Melli and Q. Tang, unpublished result). Thus, these in vivo T cell-matured DCs were immunogenic and not tolerogenic.

Taken together, we have shown that T cell-mediated inflammation in the islets also induced maturation of islet-resident DCs and their LN migration. Thus, islet inflammation results in an increase of mature islet Ag-presenting DCs in the PLNs that may lead to further priming of β cell Ag-reactive T cells. We propose that this represents a positive feedback mechanism to amplify the ongoing autoimmune response. Mature DCs arriving in the PLNs can prime more islet-reactive T cells, thus recruiting a broader repertoire of T cells to the autoimmune response. Additionally, mature DCs that remain in the islets may serve to reactivate newly arrived primed T cells to activate their effector functions and/or to reprime resident T cells to maintain their cytotoxic potential (44, 45), leading to increased β cell destruction. This model is consistent with a previous report demonstrating an essential role of DCs in sustaining anti-islet immune responses (12, 13) and provides a mechanistic framework of DC function in this context. Furthermore, results from our study suggest that therapeutic interventions that interrupt this amplification loop may help to prevent further tissue destruction and preserve the remaining islet mass in patients afflicted with autoimmune diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Jiang, C. McArthur, P. Koudria, and C. Sorensen for technical assistance; Dr. Edward Leiter for histological analysis of the NOD.MIP-GFP pancreatic samples; and P. Derish and Drs. J. A. Bluestone, A. K. Abbas, and S. Bailey-Bucktrout for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation research grant (to M.F.K. and Q.T.) and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R21 AI66097 and R37 AI46643). R.S.F. was funded by the Larry L. Hillblom foundation.

Abbreviations used in this paper: T1D, type 1 diabetes; CMTMR, 5(and 6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine; DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DC, dendritic cell; LN, lymph node; MIP, mouse insulin 1 promoter; mOVA, membrane-bound chicken OVA; PLN, pancreatic LN; RIP, rat insulin promoter; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Note added in proof. New experimental evidence by A. Martin and Q. Tang since the acceptance of this paper suggests that a portion of the mature CD40highGFP− DCs in inflamed islets are recent recruits from the circulation.

References

- 1.Turley S, Poirot L, Hattori M, Benoist C, Mathis D. Physiological β cell death triggers priming of self-reactive T cells by dendritic cells in a type-1 diabetes model. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1527–1537. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You S, Belghith M, Cobbold S, Alyanakian MA, Gouarin C, Barriot S, Garcia C, Waldmann H, Bach JF, Chatenoud L. Autoimmune diabetes onset results from qualitative rather than quantitative age-dependent changes in pathogenic T-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:1415–1422. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregori S, Giarratana N, Smiroldo S, Adorini L. Dynamics of pathogenic and suppressor T cells in autoimmune diabetes development. J. Immunol. 2003;171:4040–4047. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Q, Adams JY, Penaranda C, Melli K, Piaggio E, Sgouroudis E, Piccirillo CA, Salomon BL, Bluestone JA. Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity. 2008;28:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart DN, Fabre JW. Demonstration and characterization of Ia-positive dendritic cells in the interstitial connective tissues of rat heart and other tissues, but not brain. J. Exp. Med. 1981;154:347–361. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderon B, Suri A, Miller MJ, Unanue ER. Dendritic cells in islets of Langerhans constitutively present β cell-derived peptides bound to their class II MHC molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6121–6126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801973105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:351–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231606698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uno S, Imagawa A, Okita K, Sayama K, Moriwaki M, Iwahashi H, Yamagata K, Tamura S, Matsuzawa Y, Hanafusa T. Macrophages and dendritic cells infiltrating islets with or without β cells produce tumor necrosis factor-α in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:596–601. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen A, Homo-Delarche F, Hooijkaas H, Leenen PJ, Dardenne M, Drexhage HA. Immunohistochemical characterization of monocytes-macrophages and dendritic cells involved in the initiation of the insulitis and β-cell destruction in NOD mice. Diabetes. 1994;43:667–675. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.5.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinomiya M, Nadano S, Shinomiya H, Onji M. In situ characterization of dendritic cells occurring in the islets of nonobese diabetic mice during the development of insulitis. Pancreas. 2000;20:290–296. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolic T, Geutskens SB, van Rooijen N, Drexhage HA, Leenen PJ. Dendritic cells and macrophages are essential for the retention of lymphocytes in (peri)-insulitis of the nonobese diabetic mouse: a phagocyte depletion study. Lab. Invest. 2005;85:487–501. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena V, Ondr JK, Magnusen AF, Munn DH, Katz JD. The countervailing actions of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells control autoimmune diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5041–5053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara M, Wang X, Kawamura T, Bindokas VP, Dizon RF, Alcoser SY, Magnuson MA, Bell GI. Transgenic mice with green fluorescent protein-labeled pancreatic β-cells. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;284:E177–E183. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Q, Adams JY, Tooley AJ, Bi M, Fife BT, Serra P, Santamaria P, Locksley RM, Krummel MF, Bluestone JA. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Dudziak D, Wardemann H, Eisenreich T, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Visualizing dendritic cell networks in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1243–1250. doi: 10.1038/ni1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinhardt RL, Hong S, Kang SJ, Wang ZE, Locksley RM. Visualization of IL-12/23p40 in vivo reveals immunostimulatory dendritic cell migrants that promote Th1 differentiation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1618–1627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, Ye J, Masteller EL, McDevitt H, Bonyhadi M, Bluestone JA. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1455–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gapp DA, Leiter EH, Coleman DL, Schwizer RW. Temporal changes in pancreatic islet composition in C57BL/6J-db/db (diabetes) mice. Diabetologia. 1983;25:439–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00282525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiter EH, Reifsnyder P, Driver J, Kamdar S, Choisy-Rossi C, Serreze DV, Hara M, Chervonsky A. Unexpected functional consequences of xenogeneic transgene expression in β-cells of NOD mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9 Suppl. 2:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulombe M, Gill RG. Tolerance induction to cultured islet allografts: I. Characterization of the tolerant state. Transplantation. 1994;57:1195–1200. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199404270-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawiger D, Inaba K, Dorsett Y, Guo M, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Ravetch JV, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:769–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heufler C, Koch F, Stanzl U, Topar G, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Enk A, Steinman RM, Romani N, Schuler G. Interleukin-12 is produced by dendritic cells and mediates T helper 1 development as well as interferon-γ production by T helper 1 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:659–668. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winzler C, Rovere P, Rescigno M, Granucci F, Penna G, Adorini L, Zimmermann VS, Davoust J, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Maturation stages of mouse dendritic cells in growth factor-dependent long-term cultures. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:317–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurts C, Carbone FR, Barnden M, Blanas E, Allison J, Heath WR, Miller JF. CD4+ T cell help impairs CD8+ T cell deletion induced by cross-presentation of self-antigens and favors autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:2057–2062. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz JD, Benoist C, Mathis D. T helper cell subsets in insulin-dependent diabetes. Science. 1995;268:1185–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.7761837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fife BT, Guleria I, Gubbels Bupp M, Eagar TN, Tang Q, Bour-Jordan H, Yagita H, Azuma M, Sayegh MH, Bluestone JA. Insulin-induced remission in new-onset NOD mice is maintained by the PD-1-PD-L1 pathway. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2737–2747. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, Ashourian N, Singh B, Sharpe A, Bluestone JA. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ormo M, Cubitt AB, Kallio K, Gross LA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science. 1996;273:1392–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang F, Moss LG, Phillips GN., Jr The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:1246–1251. doi: 10.1038/nbt1096-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkaabi KM, Yafea A, Ashraf SS. Effect of pH on thermal- and chemical-induced denaturation of GFP. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2005;126:149–156. doi: 10.1385/abab:126:2:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belkhiri A, Lytvyn V, Guilbault C, Bourget L, Massie B, Nagler DK, Menard R. A noninvasive cell-based assay for monitoring proteolytic activity within a specific subcellular compartment. Anal. Biochem. 2002;306:237–246. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura K, Shimada T, Ono E, Tanaka Y, Nagatani A, Higashi SI, Watanabe M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Why green fluorescent fusion proteins have not been observed in the vacuoles of higher plants. Plant J. 2003;35:545–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson MS, Bluestone JA. The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:447–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villadangos JA, Heath WR. Life cycle, migration and antigen presenting functions of spleen and lymph node dendritic cells: limitations of the Langerhans cells paradigm. Semin. Immunol. 2005;17:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.In’t Veld PA, Pipeleers DG. In situ analysis of pancreatic islets in rats developing diabetes: appearance of nonendocrine cells with surface MHC class II antigens and cytoplasmic insulin immunoreactivity. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:1123–1128. doi: 10.1172/JCI113669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turley SJ, Inaba K, Garrett WS, Ebersold M, Unternaehrer J, Steinman RM, Mellman I. Transport of peptide-MHC class II complexes in developing dendritic cells. Science. 2000;288:522–527. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5465.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheinecker C, McHugh R, Shevach EM, Germain RN. Constitutive presentation of a natural tissue autoantigen exclusively by dendritic cells in the draining lymph node. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1079–1090. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong X, Swaminathan S, Bachman LA, Croatt AJ, Nath KA, Griffin MD. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells in renal lymph nodes is linked to systemic and local injury to the kidney. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1096–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierre P. Dendritic cells, DRiPs, and DALIS in the control of antigen processing. Immunol. Rev. 2005;207:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurts C, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Allison J, Miller JF, Kosaka H. Constitutive class I-restricted exogenous presentation of self antigens in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:923–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang A, Bloom O, Ono S, Cui W, Unternaehrer J, Jiang S, Whitney JA, Connolly J, Banchereau J, Mellman I. Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity. 2007;27:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory mediators are insufficient for full dendritic cell activation and promote expansion of CD4+ T cell populations lacking helper function. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:163–170. doi: 10.1038/ni1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang TT, Jabs C, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. Studies in B7-deficient mice reveal a critical role for B7 costimulation in both induction and effector phases of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:733–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krummel MF, Heath WR, Allison J. Differential coupling of second signals for cytotoxicity and proliferation in CD8+ T cell effectors: amplification of the lytic potential by B7. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2999–3006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.