Abstract

The role APCs play in the transition of T cells from effector to memory remains largely undefined. This is likely due to the low frequency at which long-lived T cells arise which hinders analysis of the events involved in memory development. Herein, we used TCR transgenic T cells to increase the frequency of long-lived T cells and developed a transfer model suitable for defining the contribution of APCs to the development of CD4-T cell memory. Accordingly, naive TCR transgenic T cells were stimulated in vitro with Ag presented by different types of APCs, transferred into MHC class II-deficient (MHC II−/−) mice for parking, and the hosts were later analyzed for long-lived T cell frequency or challenged with suboptimal dose of Ag and the long-lived cells-driven memory responses were measured. The findings indicate that B cells and CD8α+ DCs sustained elevated frequencies of long-lived T cells which yielded rapid and robust memory responses upon re-challenge with sub-optimal dose of Ag. Furthermore, both types of APCs had significant Programmed Death Ligand 2 (PD-L2) expression prior to Ag stimulation, which was maintained at a high level during presentation of Ag to T cells. Blockade of PD-L2 interaction with its receptor Programmed Death (PD-1) nullified the development of memory responses. These previously unrecognized findings suggest that targeting specific APCs for Ag presentation during vaccination could prove effective against microbial infections.

Introduction

Immunological memory is the cardinal feature of the immune system that provides the fundamental basis for vaccine development (1-5). An initial encounter with the cognate antigen triggers naïve T cells to differentiate into effectors that engage in microbial clearance (1-5). Upon completion of this task the cells enter a contraction phase during which most effectors cells undergo apoptosis. Very few of the effectors (1 in 105-106) do not undergo apoptosis but become long-lived microbe-specific memory cells that will respond to future infections (2, 6). Despite the fact that few cells transit from effector to memory, the resulting increase in Ag-specific precursors enables rapid and robust responses against future encounters with the microbe (7-12). Most of the progress made to date on the development of T cell memory has involved the development of CD8+ T cell memory and late phase memory responses. Much less is understood about the development and maintenance of CD4+ T cell memory. Also, little is known on how and when the decision to become a short-lived effector versus a long-lived memory cell is made (2, 13-14). The low frequency of effectors that transit to memory and the lack of specific markers to track memory precursors have hindered progress in this field (15-16). Understanding the events that direct the effector to memory transition will likely aid in the development of effective vaccination strategies (17). We have previously shown that in vivo exposure of TCR transgenic T cells to ovalbumin 323-339 peptide (OVA) yields effector T cells, some of which produce significant IFNγ while others secrete rather modest levels of IFNγ (18). Interestingly, the IFNγ producing effectors gave rise to memory precursors that sustained rapid and robust memory responses while those with reduced IFNγ yielded delayed and moderate memory responses. Given that a homogeneous population of naïve TCR transgenic T cells was used, the assorted memory responses may reflect differential antigen presentation by various APCs rather than the function of T cell intrinsic factors. The results presented here demonstrate that B cells and the CD8α+ DC subset support transition from effector to memory and generate significant memory precursors that sustain rapid and robust responses, the hallmark of memory (19-24). Furthermore, both cells express higher levels of PD-L2, a ligand for the negative regulator of T cell activation PD-1, in their resting state. This is maintained during presentation of OVA and blockade of the interaction between PD-L2 and PD-1 drastically reduced memory responses. Therefore, specific types of APCs such as B cells and CD8α+ DCs display an intrinsic expression of PD-L2 prior to and during presentation of antigen, thus supporting transition from effector to memory possibly by restraining hyperactivation of T cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

DO11.10/scid or DO11.10/RAG2−/− transgenic mice (H-2d) expressing a T cell receptor specific for OVA peptide were previously described (25). Balb/c mice (H-2d) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN. MHC II−/− Balb/c mice (cAN 129 S6 (B6) Ii tm1 Liz−/−) (H-2d) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME. All animals were used in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Missouri institutional animal care and use committee.

Antigens

OVA peptide (SQAVHAAHAEINEAGR) encompasses aa residues 323-339 of chicken ovalbumin (OVA) and is immunogenic in Balb/c (H-2d) mice. Influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) peptide aa residues 110-120 (SFERFEIFPKE) is also immunogenic in Balb/c mice and was therefore used as a negative control (26). Peptides were purchased from EZBiolab (Carmel, IN).

5(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)

Naïve splenic DO11.10 CD4+ T cells were isolated using Miltenyi’s magnetic bead positive selection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were then labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as described (18, 27). Briefly, the T cells (10 × 106 cells / ml) were incubated with 10 μM CFSE at 37°C for 13 min. The labeled cells were then washed twice with ice-cold DMEM-10% FCS before use.

Purification of antigen presenting cells

Dendritic Cells

Mature dendritic cells were purified from Balb/c mice by differential adherence as described (28-29). Briefly, spleens were digested in a collagenase solution, then DCs were isolated using a BSA density gradient. These isolated DCs were plated for 1.5 h at 37°C in plain DMEM with no fetal serum. The plates were washed to remove non-adherent cells, and incubated further for 12 h at 37°C in complete culture media containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Plates were then washed and the non-adherent mature dendritic cells were collected. Subsets of DCs were obtained through positive selection purification using Miltenyi microbead system and divided into CD8α+, CD8α−CD4+, CD8α−CD4−CD11c+ subsets through successive rounds of positive selection.

B cells

B cells were purified by panning as described (30). In brief, Balb/c splenic (SP) cells were incubated for 1h in flasks coated with anti-κappa light chain antibody. Flasks were then washed thoroughly to remove non-adherent cells, and lidocaine (4 mg/ml) was used to detach the captured B cells. The purified B cells were then washed twice with DMEM-10% FCS prior to use.

Macrophages

Macrophages were purified from SP of Balb/c mice using a standard adherence procedure. Briefly, SP cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C on a plastic dish. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and the remaining cells were incubated for a further 14 hours. Cultures were washed to remove non-adherent cells again leaving macrophages adhering to the plate. Macrophages were removed using a cell scraper, and washed twice with DMEM-10% FCS before use.

All purified APCs used in culture were irradiated with 3000 Rads using a MDS Nordion GammaCell Exactor irradiator.

Measurement of cytokine production by primary effector T cells

DO11.10 T cells (2 × 106 cells per well) were incubated in a 6 well plate with graded amounts of OVA peptide and DC subsets (0.4 × 106 cells/well), or macrophages (0.3 × 106cells/ well) for 60hr or B cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well) for 84 hours in a total volume of 4 ml culture media. Detection of IFNγ and IL-5 was performed by ELISA as described (31). The capture Abs were as follows: rat anti-mouse IFNγ, R4-6A2 and rat anti-mouse IL-5, TRFK5 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). The biotinylated anti-cytokine Abs were rat anti-mouse IFNγ, XMG1.2, and rat anti-mouse IL-5, TRFK4. The OD405 was measured on a SpectraMAX 340 counter (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA) using SoftMAX Pro version 3.1.1 software. Graded amounts of recombinant mouse IL-5 and IFNγ were included in all experiments to construct standard curves. The concentration of cytokines in culture supernatants was estimated by extrapolation from the linear portion of the standard curve.

Adoptive transfer of primary effector T cells into MHC II−/− hosts

CFSE-labeled DO11.10 T cells (2 × 106 cells per well) were incubated in a 6 well plate with OVA peptide and irradiated DC subsets (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), or macrophages (0.5 μM OVA, 0.3 × 106cells/ well) for 60hr or B cells (0.5 μM OVA, 2.0 × 106 cells/well) for 84 hr in a total volume of 4 ml culture media. A fraction of the cells were used to ensure the pattern of T cell activation by CFSE dilution and the remaining T cells were adoptively transferred (5 × 105 T cells per mouse) into MHC II−/− hosts i.v. into the tail vein.

Analysis of the frequency of memory T cell precursors

The spleen was harvested from MHC II−/− mice recipient of effector T cells after 4 months parking. The frequency of IFNγ, IL-4 and IL-5 producing memory precursors was determined by ELISPOT as described (32-33). Briefly, HA-multiscreen plates were coated with 100 μl/well 1 M NaHCO3 buffer containing 2 μg/ml of capture antibody. After overnight incubation at 4°C, plates were washed three times with PBS and three times with PBS containing Tween 20. Free sites were then saturated with culture medium for 2 hours at 37°C. After blocking, the media was removed and bulk splenic cells (1 × 106/100 μl/well) and wild type Balb/c bulk splenic APCs (0.2 × 106/50 μl/well) were incubated with the indicated amounts of OVA peptide or 10 μM HA peptide (50 μl/well) at 37°C, 7% CO2. After 24 hr, the plates were washed and 100 μl of 1 μg/ml biotinylated anti-cytokine antibody was added to each well. The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed, and 100 μl of avidin-peroxidase (2.5 μg/ml) was added per well. Plates were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and washed. Spots were visualized by adding 200 μl of 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate in 50mM acetate buffer. Spots were counted on an Immunospot Series 3B analyzer using Immunospot version 4.2 software. Antibody pairs used for ELISPOT were the same used for ELISA.

Analysis of memory T cell responses

After 4 months parking the MHC II−/− host mice recipient of 5 × 105 effector DO11.10 T cells were given 106 Balb/c DCs i.v. (to serve as APCs) and 24 hr later immunized with a 20 μg/mouse of OVA peptide in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) (1vol. / 1vol.) s.c. in the footpads and flanks. Five days later, SP and LN were harvested and splenic (9 × 105/well) and LN (3 × 105/well) cells were stimulated with OVA peptide presented by Balb/c splenic APCs (2 × 105/well). After 24 hr, IFNγ and IL-5 in the supernatants was detected by ELISA.

Flow cytometry

APCs and T cells were stained for the presence of costimulatory and other cell surface markers as follows. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ). Purified APCs (1 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with allophycocyanin anti-B220 (RA3.6B2), allophycocyanin anti-CD11b (M1/70), allophycocyanin anti-CD11c (HL3), PE anti-B7.1 (RMMP-1), FITC anti-B7.2 (GL1), PerCP anti-CD40 (3/23), PE anti-PD-L1 (10F.9G2), biotin anti-PD-L2 (TY25) or isotype control antibody for 30 min on ice. T cells were purified from spleens of DO11.10/RAG2−/− mice by Miltenyi MACS system using CD4 microbeads. Purified CD4 T cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were then incubated with FITC KJ1.26 (specific for DO11.10 TCR), PE anti-IL-7Rα (A7R34), PE anti-CCR7 (4B12), PerCP anti-CD28 (37.51), PE-Cy7 anti-PD-1 (RMP1-30) or isotype control antibody for 30 min on ice. The cells were then washed, fixed and the data collected using the Beckman Coulter CyAN flow cytometer (Miami, FL) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 8.7.1 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

For post-stimulation surface stainings, cells were cultured as in generation of memory transfer groups above. At the end of the culture period, cells were stained similarly to prestimulation. The data was collected and analyzed as above.

Blockade of PD-1/PDL-2 interactions

DO11.10 T cells (2 × 106 cells per well) were incubated in a 6 well plate with OVA peptide and irradiated DC subsets (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), or macrophages (0.5 μM OVA, 0.3 × 106cells/ well) for 60 hr or B cells (0.5 μM OVA, 2.0 × 106 cells/well) for 84 hr in the presence of anti-PD-L2 antibody (TY25) or Rat IgG at a final concentration of 5μg/ml (24). At the end of the culture period, cells were harvested and 5 × 105 T cells were transferred to MHC II−/− hosts i.v. into tail the vein for a 4-month parking.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were done using one way ANOVA.

Results

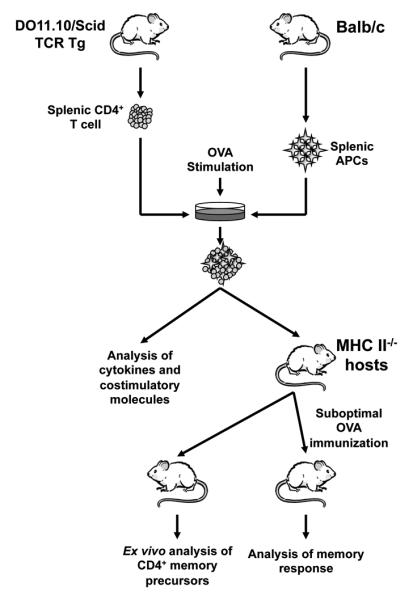

B cells and CD8α+ DCs drive induction of IFNγ-producing memory T cells

Stimulation of OVA-specific TCR transgenic monoclonal T cells with antigen yields effector T cells heterogeneous at the level of activation and IFNγ production, leading to assorted memory responses (18). These observations suggest that factors intrinsic to the T cells may not account for heterogeneity in effector or memory responses. Rather, presentation of antigen by different APCs could engender different effector or memory responses by the same T cell. Given that macrophages, B cells, and dendritic cells, including CD8 and CD4 expressing subsets (34-36), function as major presenting cells we sought to test for memory development when Ag presentation is performed by these APCs. To this end a suitable Ag stimulation model was developed and adapted for testing the different APCs for induction of T cell memory (Fig.1). Accordingly, OVA-specific DO11.10/RAG2−/− T cells were cultured with specific APCs isolated from MHC compatible Balb/c mice and stimulated with OVA peptide. The T cells were then transferred into MHC class II-deficient (MHC II−/−) Balb/c mice, and 4 months later the frequency of long-lived T cells was analyzed ex vivo and the memory response was determined after immunization with a suboptimal dose of OVA (Fig.1). In this model, preliminary experiments were carried out to determine the optimal stimulation conditions including the number of presenting cells, the concentration of OVA peptide, and the incubation time for each APC type that yields a common pattern of T cell division in vitro prior to transfer into the host mice. Also, the suboptimal dose of OVA peptide used for rechallenge in vivo was previously determined as the dose of peptide that induces a response in mice recipient of activated but not naïve T cells (18). As the host has no MHC II molecules, CD4 T cell development in the thymus is compromised and the mouse has very few endogenous CD4 T cells. Therefore, all CD4 T cells recovered at the end of the 4 month-parking period originate from those introduced during the initial transfer.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the animal model used to investigate development of CD4+ T cell memory.

Splenic CD4+ T cells from adult DO11.10/Scid mice are plated with irradiated (3000 × rads) purified Balb/c APCs and stimulated with OVA peptide. The T cells are then used for expression of costimulatory molecules, cytokine production, or adoptive transfer into MHC II−/− Balb/c mice. For the latter, after 4 months parking, the hosts are either used to analyze the frequency of memory T cell precursors prior to any re-challenge with OVA peptide or given Balb/c DC and immunized with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide in CFA and used to evaluate IFNγ memory responses.

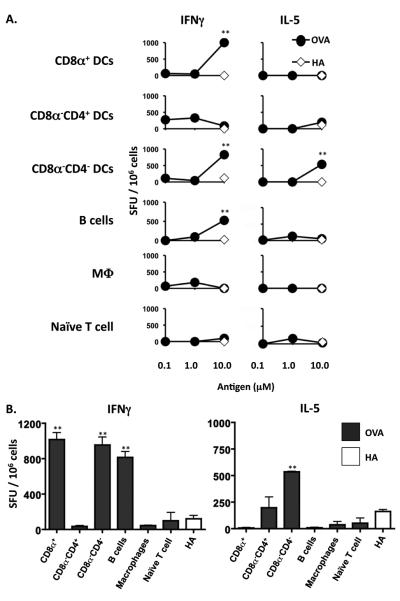

To determine the frequency of long-lived T cells that survive for 4 months after transfer into the host mice, splenic cells were harvested from the MHC II−/− Balb/c hosts and assayed for intracellular IFNγ and IL-5 by ELISPOT. The data presented in Figure 2 shows that there are significant numbers of specific long-lived T cells producing IFNγ in hosts recipient of T cells stimulated with B cells, CD8α+, and CD8α−CD4− DCs (Fig.2 A and B, left panels). Cytokine secretion is specific because the control HA peptide did not induce responses above background levels. Interestingly, in addition to the IFNγ producing long-lived T cells , the CD8α−CD4− DCs also induced significant numbers of long-lived cells that produced IL-5 (Figure 2A and B, right panels). Overall, development of long-lived T cells which likely represent memory precursors occurs when the initial encounter with Ag is mediated by specific types of APCs such as B cells, CD8α+, and CD8α−CD4− DCs.

Figure 2. CD8α+ and CD8α−CD4− DCs, and B cells induce the generation of memory precursors.

MHC II−/− Balb/c mice recipient of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells stimulated in vitro with 0.5 μM (for B cells and M03D5) or 1.0 μM (for DC subsets), OVA peptide presented by specific APC were sacrificed 4 months after transfer. The splenic cells (1 × 106 per well) were then stimulated with graded amounts of OVA peptide presented on MHC II+/+ Balb/c splenic APCs (0.2 × 106 per well) and (A) the frequency of IFNγ and IL-5 producing cells was determined by ELISPOT and expressed as spot forming units (SFU) per 106 cells. (B), bar graph representing the frequency of cytokine producing cells obtained with 10 μM OVA peptide stimulation. ** p<0.01. p values represent comparison of IFNγ production in 10μM OVA peptide groups to that in 10μM HA peptide. Data representative of 3 independent experiments with 3 mice per group.

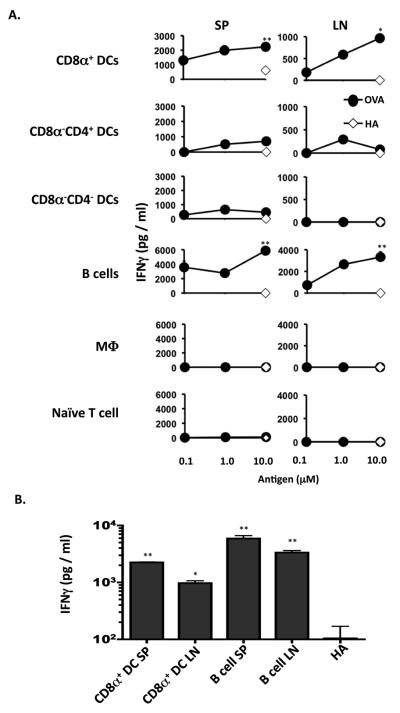

To evaluate the response of these potential memory precursors upon re-challenge with Ag, the MHC II−/− host mice were adoptively transferred with MHCII+/+ DCs to serve as APCs and the animals were immunized with a previously determined suboptimal dose of OVA peptide (20 μg peptide/mouse) (18). Five days later the spleen (SP) and LN cells were harvested and analyzed for production of IFNγ by ELISA. The data presented in Figure 3 shows that a dose-dependent IFNγ memory response developed in both organs when the initial encounter with Ag was carried out by CD8α+ DC subset or B cells (Fig.3A). The CD8α− subsets, whether CD4+ or CD4−, and M03C6 did not support the development of significant memory responses in either organ. On the other hand, the CD8α+ DCs yielded long-lived T cell memory precursors similar to B cells but the memory responses were 2 to 3 times higher for B cells than CD8α+ DC in both the SP and LN (Fig. 3B). This is likely reflective of quantitative difference in IFNγ production by precursor T cells that arise under stimulation by different APCs. Finally, the production of IL-5 was analyzed, but none was found (not shown). It should be noted that the CD8α−CD4− DC subset which yielded significant numbers of long-lived T cells showed no memory responses. Overall, these results indicate that presentation of Ag by B cells and CD8α+ DCs during the initial encounter sustains the development of long-lived T cells that support significant IFNγ memory response.

Figure 3. CD8α+ DC and B cells support the development of IFNγ–producing memory T cells.

MHC II−/− Balb/c mice recipient of DO11.10 CD4+ T cells stimulated in vitro with OVA peptide presented by specific APC were given, 4 months after T cell transfer, MHC II+/+ Balb/c DC and challenged with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide (20 μg/mouse) in CFA (1vol /1 vol). Five days later the mice were sacrificed and the SP (9 × 105 per well) and LN (3 × 105 per well) were stimulated with OVA or control HA peptide presented on MHC II+/+ Balb/c APC splenocytes (2 × 105 per well). (A), IFNγ responses obtained by ELISA upon stimulation with graded concentrations of OVA peptide or 10μM HA peptide. (B) Amount of IFNγ obtained with 10μM OVA peptide stimulation for mice recipient of T cells that initially encountered Ag presented by CD8α+ DCs or B cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. p values represent comparison of IFNγ production in 10μM OVA peptide groups to that in 10μM HA peptide. Data representative of three independent experiments with three mice per group.

Antigen presenting cells supporting IFNγ but not IL-5 producing effectors sustain memory development

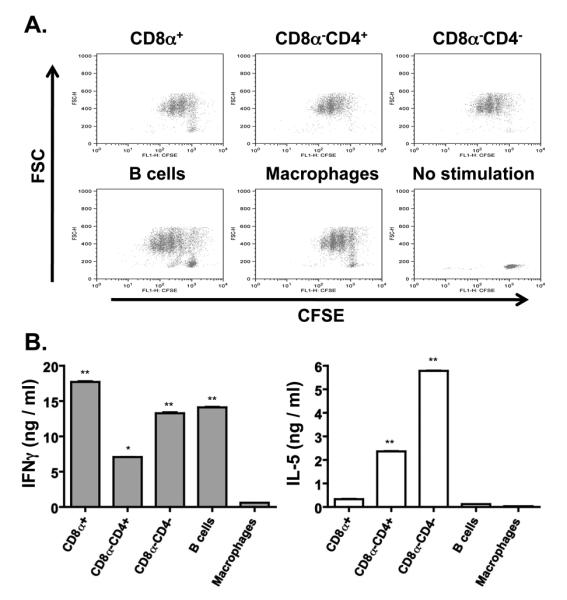

Presentation of Ag by APCs and recognition by T cells involves interaction with costimulatory molecules and production of effector cytokines. One would envision that these events would influence the transition from effector to memory and the development of memory responses (37-40). To determine the type of cytokine produced by the T cell during the initial Ag presentation by the specific APCs, naïve T cells were stimulated with OVA peptide presented by the different APCs and cytokine (IFNγ and IL-5) production was measured. The results presented in Figure 4 show that naïve T cells were activated and underwent cell division upon stimulation with OVA presented by DC subsets, B cells, or macrophages (Fig. 4A). However, CD8α+ DCs and B cells which sustained transition to memory yielded effectors that produce significant amounts of IFNγ but no measurable IL-5 (Fig. 4B). Stimulation with M03C6 which induced T cell activation and division did not yield IFNγ or IL-5 producing effectors. In contrast, the CD8α−CD4+ and CD8α− CD4− DC subset yielded mixed effector T cells producing IFNγ and IL-5 cytokines. Given that CD8α+ DCs and B cells sustained memory responses while CD8α− DCs and macrophage did not, these findings suggest that transition to memory requires antigen presentation by APCs that support the generation of IFNγ but not IL-5 producing effectors.

Figure 4. CD8α+ DC- and B cell-stimulated DO11.10 CD4+ T cells produce IFNγ but not IL-5.

CFSE-labeled DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (2 × 106 cells/well) were stimulated with OVA peptide (1.0 μM DC subsets, 0.5 μM B cells and M03D5) presented by CD8α+ DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4+ DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4− DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), M03D5 (0.3 × 106 cells/well), or B cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well). (A) shows CFSE dilution by the T cells upon presentation of OVA peptide by the indicated APCs. CFSE-labeled unstimulated T cells (No stimulation) are included as control. (B) shows IFNγ and IL-5 production as measured by ELISA for each of the indicated stimulation cultures. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Data representative of four independent experiments.

Antigen presenting cells expressing higher levels of PD-L2 sustain induction of T cell memory

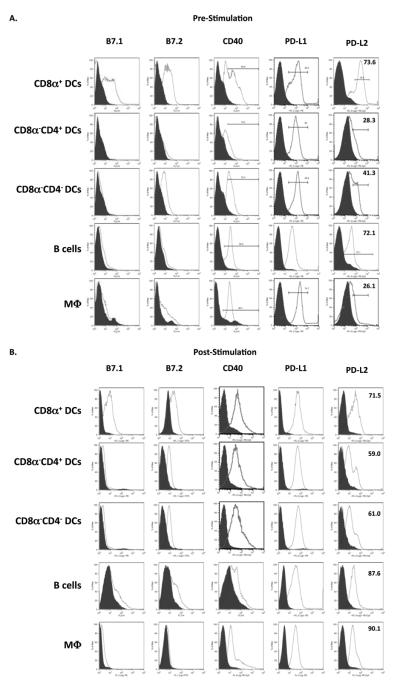

Costimulatory molecules and their ligands effect T cell activation and differentiation (41-42). While B7.1 and B7.2 have long been known to exert a stimulatory function on T cell activation, other costimulatory molecules such as Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) and PD-L2 are rather involved in negative regulation of T cell activation (21-24, 41, 43). The PD-1 molecule, which functions as a receptor for PD-L1 and PD-L2, is expressed in low amounts on resting T cells but has been shown to be upregulated upon long-term stimulation, resulting in exhaustion of the T cells (42). These observations clearly indicate that interaction of costimulatory molecules with their ligands regulates T cell activation and the resulting cytokine production at the effector phase. Since only in vitro primary cultures where IFNγ but no IL-5 was produced yielded effective memory responses, it is possible that differential expression of specific costimulatory molecules by APCs influences T cell activation, cytokine production and transition to memory. To address this premise we began by performing cell surface staining on both the APCs and T cells before and after in vitro stimulation with antigen. Accordingly, purified DC subsets, macrophages and B cells were stained for surface expression of B7.1, B7.2, CD40, PD-L1, and PD-L2 both before and after incubation with Ag and DO11.10 T cells (Fig. 5). The data presented in Figure 5A shows that prior to culture with T cells, CD8α+ DCs and B cells have higher expression of PD-L2 (73.6% and 72.1%, respectively) than CD8α−CD4−, CD8α−CD4+ or macrophages. It is interesting to note that the CD8α−CD4− DCs, which are capable of inducing long-lived T cells that do not mount a memory response have an intermediate level of PD-L2 (41.3%) compared to CD8α−CD4+ DCs (28.3%) and macrophages (26.1%). B7.1 and B7.2 molecules are highly expressed on CD8α+ DCs but not on B cells and thus may not correlate with memory development. After incubation with Ag and DO11.10 T cells, the expression of B7.1, B7.2, CD40, PD-L1 and PD-L2 on CD8α+ DCs remained at levels comparable to those observed prior to Ag stimulation (Fig. 5B). For B cells, CD40, PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression also remained at levels similar to those observed prior to Ag stimulation but B7.1 and B7.2 had a slight increase in their expression. Interestingly, while the expression of CD40, B7.1, B7.2 and PD-L1 on CD8α−CD4−, CD8α−CD4+, and macrophages remained similar to levels observed prior to Ag stimulation, the expression of PD-L2 increased on all types of APCs. Overall, PD-L2 expression was high on CD8α+ DCs and B cells prior to and after Ag stimulation but increased on the other APCs after stimulation with Ag, possibly suggesting that PD-L2 effects transition to memory when expressed on the APCs at the beginning of interaction with T cells.

Figure 5. Pattern of costimulatory molecules expressed on APCs prior to and post culture with DO11.10 T cells.

A. Freshly purified CD8α+ DCs, CD8α−CD4+ DCs, CD8α−CD4− DCs, M03D5, or B cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies specific for B7.1, B7.2, CD40, PD-L1, and PD-L2 as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed by flow cytometry. B. Purified CD8α+ DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4+ DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4− DCs (0.4 × 106 cells/well), M03D5 (0.3 × 106 cells/well), or B cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well) were incubated with CD4+ DO11.10 T cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well) and OVA peptide. The cells were then stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies specific for B7.1, B7.2, CD40, PD-L1, and PD-L2. The numbers indicate percent of marker positive cells relative to isotype control (filled) among cells gated on either CD11c (DCs), CD11b (M03D5) or B220 (B cells). Data representative of three independent experiments.

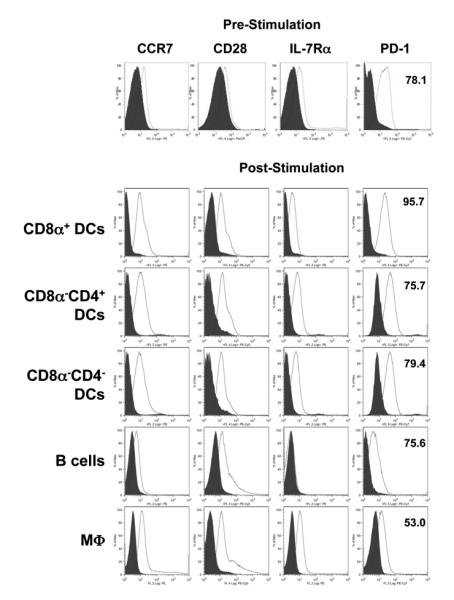

If PD-L2 on APCs plays a role in the induction of T cell memory, its receptor PD-1 should be available on the T cells to facilitate interactions with APCs and transition of T cells from effector to memory precursors. To begin investigation of the role PD-L2/PD-1 interactions may play in the transition of T cell memory we tested the T cells for expression of PD-1 as well as other markers such as CCR7, CD28, and IL-7Rα before and after stimulation with Ag. Figure 6 shows that prior to Ag stimulation, the T cells express PD-1 significantly but CCR7, CD28 and IL-7Rα were at basal levels (Fig. 6, top panel). While PD-1 is usually at low levels on naïve polyclonal T cells (44), the higher PD-1 expression observed here may be related to the fact that the DO11.10 T cells are homogeneous TCR transgenic T cells that come from a lymphopenic environment. Subsequent to stimulation with Ag presented on specific APCs, the expression of PD-1 increased from 78.1 to 95.7% when the APCs were CD8α+DCs, remained at similar levels as prior to stimulation when the APCs were CD8α− DCs or B cells and decreased to 53% with macrophages (Fig 6. panels 2-6). The expression of CCR7, CD28 and IL-7Rα increased significantly except when the presenting cells were B cells where CCR7 and IL-7Rα remained at basal levels. These results indicated the naïve T cells in this model express PD-1, the ligand for PD-L2 and maintain it at a significant level during Ag stimulation and interaction with APCs.

Figure 6. Pattern of costimulatory molecules expression on DO11.10 T cells before and after stimulation with antigen.

DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well) were stained with antibodies specific for CCR7, CD28, IL-7Rα, and PD-1 before and after stimulation with OVA peptide presented on CD8α+ DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4+ DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4− DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), M03D5 (0.5 μM OVA, 0.3 × 106cells/ well), or B cells (0.5 μM OVA, 2.0 × 106 cells/well) as described in Material and Methods. The histograms show staining of the cells gated on KJ1-26 versus isotype control (filled). The numbers indicate the percent of positive cells for the indicated markers. Data representative of three independent experiments.

PD-1/PD-L2 interactions influence development of T cell memory

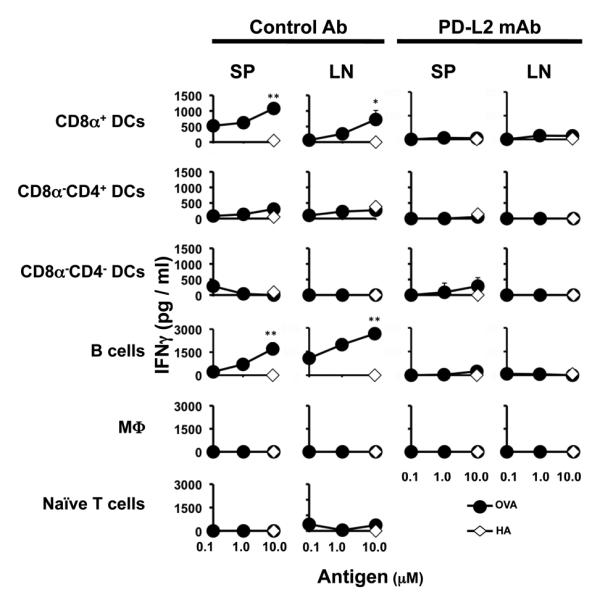

In order to test the effect the interaction of PD-1 with its ligand PD-L2 might have on the development of memory, DO11.10 T cells were stimulated with OVA peptide presented on different types of APCs in the presence of anti-PD-L2 blocking antibody (24) or a Rat IgG isotype control. The cells were then adoptively transferred into MHC II-deficient mice and parked for 4 months. Subsequently, the hosts were given MHC II+/+ DCs and immunized with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide in CFA. Five days post immunization, the SP and LN were harvested and production of IFNγ cytokine was determined by ELISA. As can be seen in Figure 7, blockade of PD-L2 with anti-PD-L2 antibody during the in vitro stimulation with OVA peptide presented on CD8α+ DCs nullified IFNγ memory responses in both the SP and LN upon in vivo challenge with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide. The isotype control antibody had no such effect and significant IFNγ responses developed in both the SP and LN. Similar results were observed when B cells were used in the initial presentation of OVA in vitro as memory IFNγ responses developed when in vitro stimulation was carried out in the presence of isotype control but not anti-PD-L2 antibody (Fig 7, fourth panel from top). No IFNγ memory response was observed with any of the other APCs whether the in vitro stimulation was carried out in the presence of anti-PD-L2 antibody or the isotype control indicating that only CD8α+ DC and B cells support effector to memory transition as was observed in Figure 3. Overall, the results presented here indicate that APCs expressing PD-L2 support the development of memory and interaction with PD-1 on the T cells is required during the initial encounter with Ag.

Figure 7. Blockade of PD-1/PD-L2 interaction interferes with induction of T cell memory by CD8α+ DC and B cells.

DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (2.0 × 106 cells/well) were stimulated with OVA peptide presented on CD8α+ DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4+ DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), CD8α−CD4− DCs (1.0 μM OVA, 0.4 × 106 cells/well), M03D5 (0.5 μM OVA, 0.3 × 106cells/ well), or B cells (0.5 μM OVA, 2.0 × 106 cells/well) in the presence of 5μg/ml anti-PD-L2 antibody or rat IgG isotype control. After extensive washing the T cells were adoptively transferred into MHC II−/− host mice. Four months after transfer, the mice were given MHC II+/+ Balb/c DC and challenged with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide (20 μg/mouse) in CFA (1 vol. / 1 vol.). Five days later the mice were sacrificed and the SP (9 × 105 per well) and LN (3 × 105 per well) cells were stimulated with OVA or control HA peptide presented on MHC II+/+ Balb/c APC splenocytes (2 × 105 per well). IFNγ responses obtained upon stimulation with graded concentrations of OVA peptide or 10μM HA peptide were measured by ELISA. MHC II−/− Balb/c mice recipient of unstimulated DO11.10 CD4+ T cells (Naïve T cells) are included as control. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Data representative of three independent experiments with 3-4 mice per group.

Discussion

The role APCs might play in the transition of CD4 T cells from effector to memory remains largely undefined. Here we developed a model in which naïve CD4 T cells are stimulated in vitro with Ag presented by specific types of APCs, transferred into MHC II−/− deficient mice for parking and the hosts were later used to analyze the development of T cell memory (Fig. 1). The findings indicate that transition from effector to memory and the development of rapid and robust memory responses is restricted to T cells that encountered Ag on specific types of APCs during the initial stimulation (Fig. 2 and 3). Indeed CD8α+, CD8α−CD4− DCs and B cells serving as presenting cells during the initial encounter with OVA peptide yielded significantly greater numbers of long-lived T cells than CD8α−CD4+ DCs and macrophages (Fig.2). However, upon rechallenge with a suboptimal dose of OVA peptide, only the precursors generated from stimulation with CD8α+ DCs and B cells sustained rapid and robust memory IFNγ responses (Fig. 3). The long-lived T cells generated upon stimulation with CD8α−CD4− DCs developed delayed and weaker responses upon rechallenge with suboptimal dose of OVA peptide (not shown). The fact that OVA peptide-loaded CD8α+ DCs yielded IFNγ-producing T cells during the in vitro stimulation bodes well with earlier observations demonstrating that this subset specifically support the differentiation of Th1 cells (45-47). It is thus not surprising that both the long-lived T cells generated under CD8α+ stimulation and the resulting memory response are of Th1 type T cells.

Lately, it has been suggested that memory development occurs as a result of exposure to low amounts of antigen such as residual traces of protein leftover after viral clearance (48). Also, late arrival of T cells to local lymph nodes, which subjects the lymphocytes to suboptimal residual antigen, leads to the generation of memory (49). These observations which suggest that development of T cell memory results from suboptimal Ag stimulation and moderate T cell activation at the initial effector phase, find support in recent studies demonstrating that T cells that undergo restrained activation during the early stages of the effector response yield better memory responses (50). From these observations it is logical to envision that the type of APCs that favor the development of memory would be endowed with means to control the activation of effector T cells and their transition to memory. In this line of reasoning, we tested the APCs for expression of costimulatory molecules that regulate interactions with and activation of T cells. Surprisingly, PD-L2 was highly expressed on CD8α+ DCs and B cells prior to incubation with T cells and remained at significant levels during presentation of OVA peptide to DO11.10 T cells (Fig.5). Interestingly, PD-1, the receptor for PD-L2, was also expressed on the surface of the DO11.10 T cells prior to Ag stimulation and remained highly expressed during presentation of OVA peptide by the APCs (Fig. 6). The interactions of PD-1 with its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) have been viewed as negative regulatory pathways of T cell activation (43, 51). In fact, chronicity of microbial infections was recently attributed to the up-regulation of PD-L1/L2 expression on dendritic cells and other APCs during infection, which leads to downregulation of T cell function and the consequent microbial persistence (52-56). Our findings, though, suggest that expression of PD-L2 on CD8α+ DCs and B cells and interaction with PD-1 on T cells at the initial activation stage sustains transition to memory which provides another functional significance in addition to the previously suggested role in induction of iTregs (57) and tolerance (58). The argument in favor of transition from effector to memory is supported by the observation that blockade of PD-1/PD-L2 interactions with anti-PD-L2 antibody during the initial stimulation nullifies the generation of T cell memory by both CD8α+ DCs and B cells (Fig. 7). However, given that PD-1 and PD-L2 interactions yielded both stimulatory and inhibitory signals depending on the model system used (59-60) the question remains open as to whether transition to memory involves interaction of PD-L2 with yet undefined molecules beside PD-1. Nevertheless, the observation made herein bodes well with reports indicating that heightened activation and proliferation leads to a reduction in the numbers of responding memory cells (50).

The CD8α−CD4− DCs, despite having reduced PD-L2 expression, supported the development of long-lived T cells that did not yield rapid and robust IFNγ memory responses. This suggests that a limited threshold of activation needed to be in place at the initial stimulation in order to generate long-lived memory precursors that respond to suboptimal dose of Ag during rechallenge. Also, the cytokine milieu during the initial encounter with antigen included both Th1 and Th2 effectors. While this is not surprising as CD8α− DC stimulation can differentiate naïve T cells into Th2 (45-47), the presence of a Th2 cytokine during transition to memory may condition the long-lived Th1 cells for minimal memory responses during rechallenge with suboptimal dose of Ag. Nevertheless, it seems that adequate control of the initial activation by PD-1/PD-L2 interactions is required to generate long-lived T cells that sustain robust and rapid memory responses upon challenge with a suboptimal dose of Ag.

Overall, this study has identified CD8α+ DCs and B cells as antigen presenting cells that support CD4 T cell effector to memory transition and the generation of rapid and robust memory responses upon challenge with suboptimal dose of Ag. Both types of APCs express PD-L2 whose interaction with PD-1 on T cells seems to serve as a rheostat to control the level of T cell activation and thereby effector to memory transition. Strategies that target these cells for Ag presentation during immunization could be devised for the development of effective vaccines.

Footnotes

This work was supported by RO1AI048541 and R21HD060089 (to H.Z.) from NIH. D.M.T. and J.A.C. were supported by Life Sciences Fellowships from the University of Missouri, Columbia. C. M. H. was supported by a training grant GM008396 from NIGMS.

- LN

- lymph nodes

- PD-1

- programmed death 1

- PD-L1

- programmed death ligand

- PD-L2

- programmed death ligand 2

- OVA

- ovalbumin

- SP

- spleen.

References

- 1.Doherty PC, Topham DJ, Tripp RA. Establishment and persistence of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell memory. Immunol Rev. 1996;150:23–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nri778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Cytokine control of memory T-cell development and survival. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:269–279. doi: 10.1038/nri1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Parijs L, Abbas AK. Homeostasis and self-tolerance in the immune system: turning lymphocytes off. Science. 1998;280:243–248. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaech SM, Hemby S, Kersh E, Ahmed R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:837–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutton RW, Bradley LM, Swain SL. T cell memory. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:201–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Nelson JA, Sexton GJ, Hanifin JM, Slifka MK. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat Med. 2003;9:1131–1137. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou S, Hyland L, Ryan KW, Portner A, Doherty PC. Virus-specific CD8+ T-cell memory determined by clonal burst size. Nature. 1994;369:652–654. doi: 10.1038/369652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London CA, Perez VL, Abbas AK. Functional characteristics and survival requirements of memory CD4+ T lymphocytes in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:766–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers PR, Dubey C, Swain SL. Qualitative changes accompany memory T cell generation: faster, more effective responses at lower doses of antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2338–2346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varga SM, Welsh RM. Stability of virus-specific CD4+ T cell frequencies from acute infection into long term memory. J Immunol. 1998;161:367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbertson J, Biederman E, Bennett KE, Kondrack RM, Bradley LM. Withdrawal of stimulation may initiate the transition of effector to memory CD4 cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:1095–1102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stockinger B, Kassiotis G, Bourgeois C. CD4 T-cell memory. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Activated and memory CD8+ T cells can be distinguished by their cytokine profiles and phenotypic markers. J Immunol. 2000;164:208–216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homann D, Teyton L, Oldstone MB. Differential regulation of antiviral T-cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T-cell memory. Nat Med. 2001;7:913–919. doi: 10.1038/90950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berzofsky JA, Ahlers JD, Belyakov IM. Strategies for designing and optimizing new generation vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:209–219. doi: 10.1038/35105075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell JJ, Ellis JS, Guloglu FB, Tartar DM, Lee HH, Divekar RD, Jain R, Yu P, Hoeman CM, Zaghouani H. Early effector T cells producing significant IFN-gamma develop into memory. J Immunol. 2008;180:179–187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:116–126. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subudhi SK, Zhou P, Yerian LM, Chin RK, Lo JC, Anders RA, Sun Y, Chen L, Wang Y, Alegre ML, Fu YX. Local expression of B7-H1 promotes organ-specific autoimmunity and transplant rejection. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:694–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI19210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salama AD, Chitnis T, Imitola J, Ansari MJ, Akiba H, Tushima F, Azuma M, Yagita H, Sayegh MH, Khoury SJ. Critical role of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway in regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2003;198:71–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansari MJ, Salama AD, Chitnis T, Smith RN, Yagita H, Akiba H, Yamazaki T, Azuma M, Iwai H, Khoury SJ, Auchincloss H, Jr., Sayegh MH. The programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway regulates autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198:63–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto K, Inoue H, Nakano T, Tsuda M, Yoshiura Y, Fukuyama S, Tsushima F, Hoshino T, Aizawa H, Akiba H, Pardoll D, Hara N, Yagita H, Azuma M, Nakanishi Y. B7-DC regulates asthmatic response by an IFN-gamma-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2004;172:2530–2541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Koyanagi A, Azuma M, Yagita H, Okumura K. Blockade of B7-H1 on macrophages suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation by augmenting IFN-gamma-induced nitric oxide production. J Immunol. 2005;175:1586–1592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy KM, Heimberger AB, Loh DY. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science. 1990;250:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Legge KL, Min B, Bell JJ, Gregg R, Caprio J, Zaghouani H. Neonatal immunity develops in a transgenic TCR transfer model and reveals a requirement for elevated cell input to achieve organ-specific responses. J Immunol. 2001;167:2585–2594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, Ebner S, Kampgen E, Eibl B, Niederwieser D, Schuler G. Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood. An improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods. 1996;196:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romani N, Bhardwaj N, Pope M, Koch F, Swiggard WJ, Doherty UO, Witmer-Pack MD, Hoffman L, Schuler G, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Dendritic Cells. In: W. D, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA, Blackwell C, editors. Weirs Handbook of Experimental Immunology. Blackwell Science; Cambridge, MA: 1996. pp. 156.151–156.114. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wysocki LJ, Sato VL. “Panning” for lymphocytes: a method for cell selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:2844–2848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell JJ, Min B, Gregg RK, Lee HH, Zaghouani H. Break of neonatal Th1 tolerance and exacerbation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by interference with B7 costimulation. J Immunol. 2003;171:1801–1808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min B, Legge KL, Pack C, Zaghouani H. Neonatal exposure to a self-peptide-immunoglobulin chimera circumvents the use of adjuvant and confers resistance to autoimmune disease by a novel mechanism involving interleukin 4 lymph node deviation and interferon gamma-mediated splenic anergy. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2007–2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Lee HH, Bell JJ, Gregg RK, Ellis JS, Gessner A, Zaghouani H. IL-4 utilizes an alternative receptor to drive apoptosis of Th1 cells and skews neonatal immunity toward Th2. Immunity. 2004;20:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shortman K. Burnet oration: dendritic cells: multiple subtypes, multiple origins, multiple functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:161–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Legge KL, Gregg RK, Maldonado-Lopez R, Li L, Caprio JC, Moser M, Zaghouani H. On the role of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance and modulation of autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;196:217–227. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cassell DJ, Schwartz RH. A quantitative analysis of antigen-presenting cell function: activated B cells stimulate naive CD4 T cells but are inferior to dendritic cells in providing costimulation. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1829–1840. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho IC, Glimcher LH. Transcription: tantalizing times for T cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kieper WC, Tan JT, Bondi-Boyd B, Gapin L, Sprent J, Ceredig R, Surh CD. Overexpression of interleukin (IL)-7 leads to IL-15-independent generation of memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1533–1539. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ku CC, Murakami M, Sakamoto A, Kappler J, Marrack P. Control of homeostasis of CD8+ memory T cells by opposing cytokines. Science. 2000;288:675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:336–347. doi: 10.1038/nri1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459–465. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Wu Y, Chernova T, Sobel RA, Klemm M, Kuchroo VK, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H, Ishida Y, Tsubata T, Yagita H, Honjo T. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:765–772. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu YJ, Blom B. Introduction: TH2-inducing DC2 for immunotherapy. Blood. 2000;95:2482–2483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maldonado-Lopez R, De Smedt T, Pajak B, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Leo O, Urbain J, Maliszewski CR, Moser M. Role of CD8alpha+ and CD8alpha-dendritic cells in the induction of primary immune responses in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:242–246. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maldonado-Lopez R, De Smedt T, Michel P, Godfroid J, Pajak B, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Leo O, Urbain J, Moser M. CD8alpha+ and CD8alpha-subclasses of dendritic cells direct the development of distinct T helper cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;189:587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Brown DM, Dibble JP, Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. Unexpected prolonged presentation of influenza antigens promotes CD4 T cell memory generation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:697–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Catron DM, Rusch LK, Hataye J, Itano AA, Jenkins MK. CD4+ T cells that enter the draining lymph nodes after antigen injection participate in the primary response and become central-memory cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1045–1054. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu CY, Kirman JR, Rotte MJ, Davey DF, Perfetto SP, Rhee EG, Freidag BL, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Seder RA. Distinct lineages of T(H)1 cells have differential capacities for memory cell generation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:852–858. doi: 10.1038/ni832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown JA, Dorfman DM, Ma FR, Sullivan EL, Munoz O, Wood CR, Greenfield EA, Freeman GJ. Blockade of programmed death-1 ligands on dendritic cells enhances T cell activation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 2003;170:1257–1266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Sharpe AH. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2223–2227. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trautmann L, Janbazian L, Chomont N, Said EA, Gimmig S, Bessette B, Boulassel MR, Delwart E, Sepulveda H, Balderas RS, Routy JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat Med. 2006;12:1198–1202. doi: 10.1038/nm1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedict CA, Loewendorf A, Garcia Z, Blazar BR, Janssen EM. Dendritic cell programming by cytomegalovirus stunts naive T cell responses via the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:4836–4847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jurado JO, Alvarez IB, Pasquinelli V, Martinez GJ, Quiroga MF, Abbate E, Musella RM, Chuluyan HE, Garcia VE. Programmed death (PD)-1:PD-ligand 1/PD-ligand 2 pathway inhibits T cell effector functions during human tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2008;181:116–125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmer BE, Mack DG, Martin AK, Gillespie M, Mroz MM, Maier LA, Fontenot AP. Up-regulation of programmed death-1 expression on beryllium-specific CD4+ T cells in chronic beryllium disease. J Immunol. 2008;180:2704–2712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Francisco LM, Salinas VH, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–3029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goldberg MV, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, Flies AS, Zhen L, Tuder RM, Grosso JF, Harris TJ, Getnet D, Whartenby KA, Brockstedt DG, Dubensky TW, Jr., Chen L, Pardoll DM, Drake CG. Role of PD-1 and its ligand, B7-H1, in early fate decisions of CD8 T cells. Blood. 2007;110:186–192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shin T, Yoshimura K, Crafton EB, Tsuchiya H, Housseau F, Koseki H, Schulick RD, Chen L, Pardoll DM. In vivo costimulatory role of B7-DC in tuning T helper cell 1 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1531–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang S, Bajorath J, Flies DB, Dong H, Honjo T, Chen L. Molecular modeling and functional mapping of B7-H1 and B7-DC uncouple costimulatory function from PD-1 interaction. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1083–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]