Abstract

Metastatic melanoma is an aggressive skin cancer associated with poor prognosis. The reactivation of the embryonic morphogen Nodal in metastatic melanoma has previously been shown to regulate the aggressive behavior of these tumor cells. During the establishment of left-right asymmetry in early vertebrate development, Nodal expression is specifically regulated by a Notch signaling pathway. We hypothesize that a similar relationship between Notch and Nodal may be re-established in melanoma. In this study, we investigate if cross-talk between the Notch and Nodal pathways can explain the reactivation of Nodal in aggressive metastatic melanoma cells. We demonstrate a molecular link between Notch and Nodal signaling in the aggressive melanoma cell line MV3, via the activity of an RBPJ-dependent Nodal enhancer element. We show a precise correlation between Notch4 and Nodal expression in multiple aggressive cell lines, but not poorly aggressive cell lines. Surprisingly, Notch4 is specifically required for expression of Nodal in aggressive cells, and plays a vital role in the balance of cell growth and in the regulation of the aggressive phenotype. In addition, Notch4 function in vasculogenic mimicry and anchorage independent growth in vitro is due in part to Notch4 regulation of Nodal. This study identifies an important role for cross-talk between Notch4 and Nodal in metastatic melanoma, placing Notch4 upstream of Nodal, and offers a potential molecular target for melanoma therapy.

Keywords: Notch, Nodal, Melanoma

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic melanoma is a highly aggressive skin cancer associated with poor clinical outcome. One key feature is the expression of a plastic, multipotent cellular phenotype resembling embryonic stem cells in its molecular profile (1). Both stem cells and aggressive melanoma cells participate in bidirectional communication with the microenvironment, which can profoundly influence cell behavior (2, 3). Cancer cells can exploit normally dormant embryonic pathways to promote tumorigenicity. Understanding these embryonic signals and the regulatory programs that reactivate them holds significant potential for cancer therapies, including melanoma.

Notch and Nodal are two signaling pathways that participate in embryonic stem cell maintenance and whose expression and/or activation correlates with melanoma progression (3–5). Nodal is a TGFβ superfamily member that typically associates with Type I (ALK4/5/7) and Type II (ActRIIB) Activin-like kinase receptors to activate signaling through Smad2/3/4 and promote a gene transcriptional program that includes Nodal itself and the Nodal antagonist, Lefty (6). Nodal signaling regulates multiple embryonic processes, but Nodal is not typically expressed in normal adult tissues including melanocytes (2). Re-expression of Nodal has been observed in melanoma, breast and endometrial carcinomas (2, 3, 7, 8). Nodal signaling plays an important role in the aggressive nature of metastatic melanoma, as pathway inhibition blocks tumorigenic capacity and plasticity of aggressive human melanoma cells (2, 3).

The Notch receptor family consists of four single transmembrane receptors (Notch1-4) and five membrane-bound ligands (Delta-like1, 3–4 and Jagged1-2). Structurally the four Notch receptors are somewhat similar. Notch1 and Notch2 have high homology, while Notch3 and Notch4 retain some structural differences. Compared with Notch1, Notch4 has a shortened extracellular domain and lacks the intracellular transactivation domain (TAD) and cytokine response sequence (NCR) (9, 10). For all the Notch receptors, signaling requires contact between two cells, and is propagated directly by the Notch receptor intracellular domain (ICD) that is released into the cytoplasm by sequential proteolytic cleavage steps (10, 11). The active ICD can bind co-activator proteins, such as recombination signaling binding protein-J (RBPJ) and mastermind-like proteins, and form a nuclear transcriptional activator complex. Notch signaling regulates key aspects of embryogenesis, as well as adult tissue homeostasis including maintenance of the melanocyte precursor population (12, 13). Aberrant Notch signaling can promote or inhibit oncogenesis depending upon the Notch receptor profile and the tumor or cell type (14). Notch targets implicated in cancer include c-myc, cyclin-D1, and p21/Waf1 (15).

A direct connection between the Nodal and Notch signaling pathways occurs in early embryogenesis during vertebrate body plan formation. Early in mouse development, Nodal is expressed around the transient embryonic structure termed the Node (a group of cells that secrete inductive cues to facilitate body plan organization) and is required for gene expression that regulates left-right asymmetry (16). Notch pathway components are similarly expressed (17, 18), and Notch signaling is necessary for Nodal expression at this developmental stage (19, 20). This relationship is direct, as the Notch-ICD complex can bind and drive an RBPJ-dependent enhancer element (termed the Node-specific enhancer; NDE) upstream of the Nodal gene (19, 20). The non-coding NDE region is highly conserved, indicating the possibility that a relationship also exists between Notch and Nodal in humans. While the embryonic Node itself has no direct connection to cancer biology, we hypothesized that the relationship between Notch and Nodal may be conserved or re-established in melanoma, where Nodal is reactivated (2, 3, 8). Preliminary evidence suggests that cross-talk exists between Notch4 and Nodal in an aggressive melanoma cell line (21, 22). In the present study, we explore the precise relationship between Notch4 and Nodal expression and how this cross-talk influences aggressive melanoma cell behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

Melanoma cell lines UACC1273, c81-61, and C8161 were obtained from the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (1987/1999). MV3 cells were a gift from Dr. van Muijen (University Hospital Nijmegen, The Netherlands; 2006). WM852 cells were a gift of Dr. Herlyn (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA; 2001). SK-MEL-28 cells were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA (2010). Cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat genotyping by PCR amplification at the Molecular Diagnostic/HLA Typing Core at Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago, IL (2009–2010). Cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination using a PCR ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). UACC1273, c81-6l, C8161, MV3 and WM852 cells were all maintained as described (3). SK-MEL-28 cells were maintained as ATCC recommends.

Constructs/luciferase assays

pGL3-basic was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). pGL3p containing mouse Nodal NDE was a gift from Dr. Bruneau (UCSF, San Francisco, CA) (23). RBPJ binding sites were mutated using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX). Plasmids were transfected into MV3 and C8161 cells using Arrest-In reagent (Thermo Scientific Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). Luciferase assays were performed after 48-hours (Promega). Each parameter was assayed in quadruplicate and experiments performed three times.

Reverse transcription and PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the PerfectPure RNA Cell Isolation kit (5Prime, Gaithersburg, MD). Reverse transcription of total RNA, semi-quantitative PCR (parameters in Supplemental Table 1), and real-time PCR were performed as previously described (2, 3). TaqMan® gene expression primer/probe sets (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) utilized were Nodal (Hs00250630_s1), Notch1 (Hs00413187_m1), Notch2 (Hs00225747_m1), Notch3 (Hs00166432_m1), Notch4 (Hs00270200_m1), and RPLPO large ribosomal protein (4333761F). Samples were assayed in triplicate and experiments performed three times.

Antibodies/Western blot analysis

Collection and quantification of protein lysates, SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, and Western blot analysis was carried out as described (3). Antibodies and working dilutions are in Supplemental Table 2. Membranes were reprobed following stripping of antibody-antigen complexes. Densitometric analyses were performed in Scion Image for Windows software (Scion Corp, Frederick, MD). Analyses of at least three independent experiments were used for relative average protein expression levels. Microsoft Excel was utilized for Student's t-test calculations.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol, blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (PBS), and incubated in primary antibodies (see Supplemental Table 2), followed by AlexaFluor-488 and AlexaFluor-594 secondary antibodies (1:400; Invitrogen). Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence was visualized on a ZeissMeta700 confocal microsope and images captured using Zeiss ZEN software (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Cells were counted in 7 separate fields under a 25× Zeiss LD Lci.Planapo.25×/0.8Imm.Corr. objective and mean+/−SD presented graphically.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections of a melanoma tissue array (ME1003) were purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD) and stained for Notch4 or Nodal expression as previously described (3) using primary antibody for 60 minutes. Isotype IgG at the same concentration was used as controls (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Images were captured using a Leica DM4000B microscope equipped with a DFC480 CCD camera (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL). Tissue staging was determined from the array datasheet and staining was scored as: none, weak (<25%), moderate (25–50%), strong (>50%). Immunostaining and scoring of results were performed by a trained pathologist (L.S.). In total, 61 melanoma tissue samples were evaluated. Statistical significance was determined using Z-test for two proportions (95% confidence level).

siRNA transfection

Cells were transfected with Negative Control#1, Notch1 (s9635), Notch2 (s9637), Notch3 (s9641), or Notch4 (s9644) Silencer Select Pre-designed siRNAs using siPORT-NeoFX (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX). Cells were re-transfected after 48-hours, and analyzed immediately (RNA) or 48-hours later (protein). Experiments were performed three times.

Antibody treatments

C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells seeded at confluence were antagonized with a goat anti-human Notch4 neutralizing antibody (24) (Supplemental Table 2) or goat whole molecule IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at 5µg/ml. Antibody or IgG was added at 24-hour intervals for a total incubation of 72-hours. In some experiments, 100ng/ml recombinant human Nodal (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) was also added. Cells were harvested for real-time RT-PCR, Western blotting, or flow cytometry. Preservative was removed from antibody prior to use.

Flow cytometry

Cells were treated with antibody as described, then harvested at 24-hour time-points for ViaCount or Nexin assays (Guava Technologies/Millipore). Gating parameters were set using untreated cells. Triplicate samples were averaged for each data point and experiments performed three times.

Vasculogenic mimicry assay

3D-collagen matrices were prepared as previously described (25). Cells were seeded onto matrices either untreated, or treated with goat IgG or anti-Notch4 antibody (3µg/ml) plus or minus recombinant human Nodal (100ng/ml). Antibody was added daily for 96-hours, and cultures were imaged using a Zeiss inverted microscope and Hitachi HV-C20 CCD camera (Hitachi Denshi, Woodbury, NY).

Clonogenic assay

Assays were prepared in triplicate as previously described (3), except cells were either untreated or pretreated with goat IgG or anti-Notch4 antibody (3µg/ml for 72-hours) plus or minus recombinant human Nodal (100ng/ml). 5,000 viable cells were seeded per well and macroscopic cell clusters (>50 cells) scored after 3 weeks. Triplicate wells were averaged and presented as a percentage of control +/−SD. Experiments were performed three times.

RESULTS

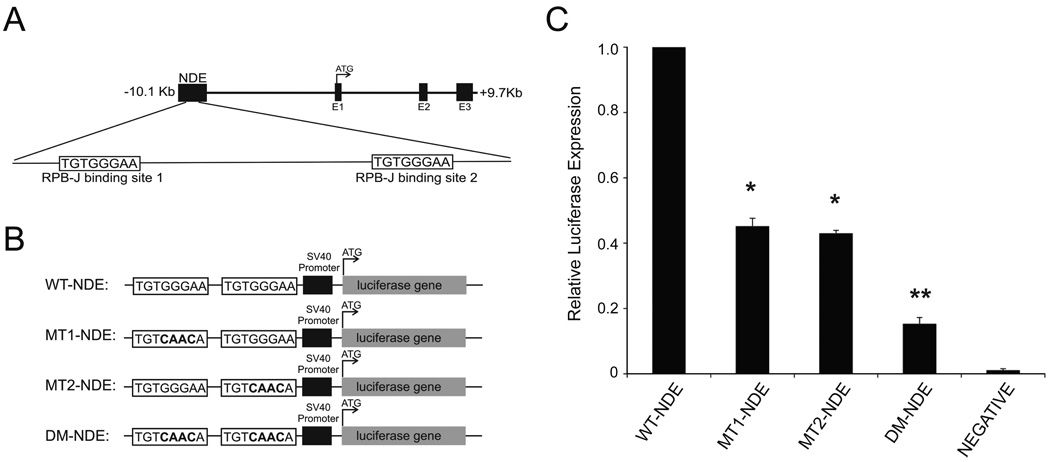

An embryonic Nodal gene enhancer element links the Notch and Nodal pathways in the aggressive melanoma cell line MV3

In an initial effort to identify a molecular link between Notch and Nodal in melanoma, we asked if an artificial reporter of the NDE region exhibits activity in the aggressive melanoma cell line MV3, which expresses Nodal mRNA and protein. The NDE is located 10KB upstream of the human Nodal gene, and contains two conserved RBPJ binding sites (Fig.1A) (19, 20). In early mouse development, binding to this enhancer region regulates Nodal gene expression, in an RBPJ-dependent manner. We reasoned that this embryonic Notch-Nodal relationship may be duplicated in melanoma, where Nodal is re-expressed (2, 3, 8). Luciferase reporter constructs containing either wild-type NDE sequence (23) or NDE sequences with mutations in one or both RBPJ binding site(s) (Fig.1B) were transfected into MV3 cells. Compared with wild-type NDE (WT-NDE), mutations in either the first or second RBPJ binding site (MT1-NDE or MT2-NDE) diminished luciferase activity to approximately half wild-type levels (45±3% [MT1-NDE]; 43±1% [MT2-NDE]; p<0.05), while mutations in both RBPJ binding sites (DM-NDE) severely reduced luciferase activity (15±1%), significantly lower than MT1-NDE or MT2-NDE levels (p<0.05) (Fig.1C). The same trend was also observed in C8161 cells (data not shown). These findings collectively suggest the possibility that the NDE region may contribute to driving Nodal re-expression in these aggressive cells via a Notch/RBPJ pathway. This initial connection between Nodal and Notch in MV3 cells provided the platform for our in-depth investigation of Notch-Nodal cross-talk in multiple melanoma cell lines.

Figure 1.

A Nodal enhancer element drives luciferase expression in MV3 cells in an RBPJ-dependent manner. A) Representation of the Nodal gene locus with upstream Node-specific enhancer (NDE) region and the two putative RBP-J binding site. B) Wild-type (WT-NDE), single mutant (MT1-NDE; MT2-NDE) and double mutant (DM-NDE) reporter constructs utilized. C) The ability of wild-type and mutant NDE constructs to drive luciferase activity in MV3 cells. pGL3-basic (NEGATIVE) was a negative control.*Significant difference from WT-NDE (p<0.05);**significant difference from MT1-NDE/MT2-NDE (p<0.05). Graph is an average of three independent experiments (+SEM).

Notch4 expression correlates with Nodal expression in multiple aggressive melanoma cell lines

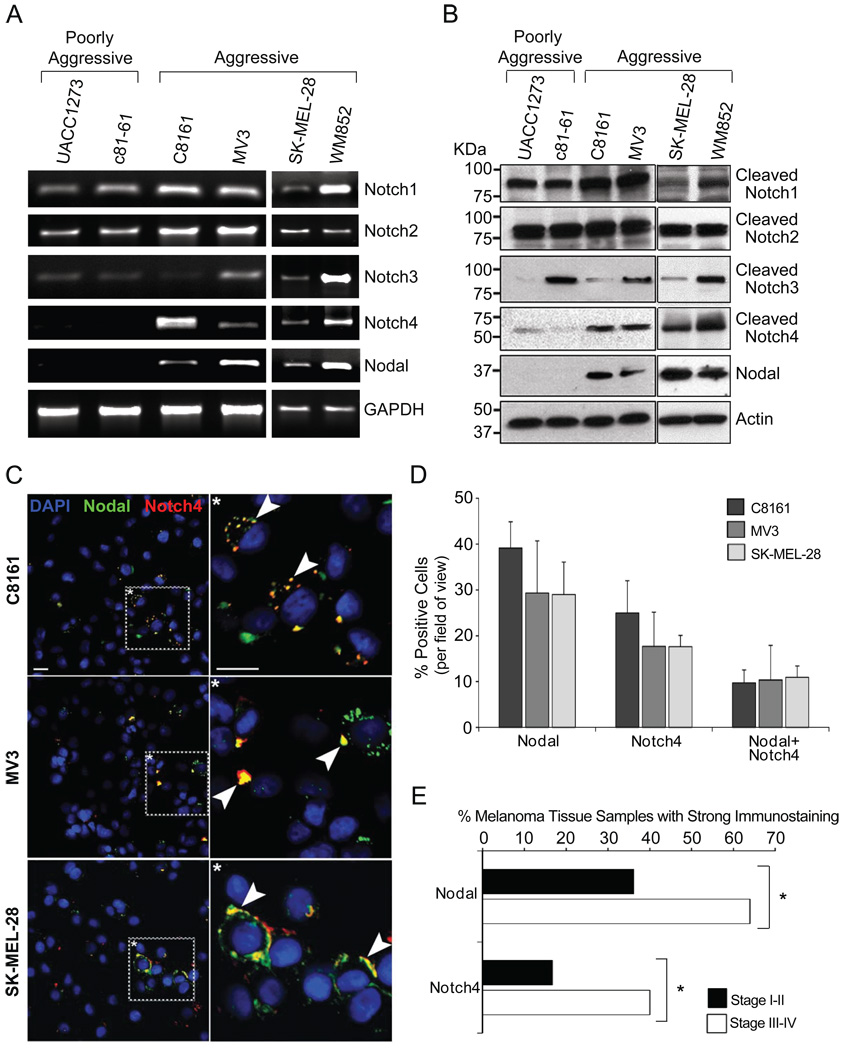

A relationship between Nodal expression and melanoma aggressiveness has been established, and in vitro Nodal expression is predominant in aggressive melanoma cells compared with poorly aggressive counterparts (3). Certain Notch receptors have been evaluated in melanoma compared with melanocytes (5, 26). To assess the complete Notch receptor expression profile of melanoma cells, we surveyed mRNA and protein levels in four aggressive (C8161, MV3, SK-MEL-28, WM852) and two poorly aggressive (UACC1273, c81-61) cell lines (Fig.2A–B). By semi-quantitative PCR, Notch1 and Notch2 genes were similarly expressed in all the cell lines (Fig.2A). Notch3 was predominantly expressed in MV3 and WM852 cells. However, Notch4 mRNA expression was observed only in the four aggressive cell lines, consistent with Nodal transcripts. At the protein level, Notch1 and Notch2 were detected in all the cell lines (Fig.2B). In contrast, Notch3 protein was observed in poorly aggressive c81-61 cells, and in aggressive MV3 and WM852 cells. Of note, Notch4 protein was detected exclusively in the four aggressive cell lines, in agreement with Nodal protein.

Figure 2.

Survey of Notch receptors and Nodal expression in melanoma cell lines. A) RNA isolated from two poorly aggressive cell lines (UACC1273, c81-61) and four aggressive cell lines (C8161, MV3, SK-MEL-28, WM852) was assayed for gene expression of Notch1–4 and Nodal by semi-quantitative PCR. GAPDH was a loading control. DNA contamination was excluded using no MMLV (not shown). B) Protein lysates were analyzed for Notch receptor and Nodal proteins by Western blotting. Actin was a loading control. C) Nodal (green) and Notch4 (red) proteins were examined by confocal microscopy in C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells (also Supplemental Fig.1). Arrowheads in inset (*) denote regions of co-localization (yellow). DAPI (blue) marks cell nuclei. White bar represents 10µm. D) Cells positive for Nodal, Notch4, or both Nodal and Notch4 (Nodal+Notch4) were independently counted using a 25X objective. For each category, mean+/−SD was graphed as a percentage of total DAPI-positive nuclei (n=7). E) Immunohistochemistry for Nodal and Notch4 was performed on serial sections of a human melanoma tissue array. The number of tissue samples showing strong staining (>50%) was graphed as a percentage of total samples evaluated (for Stage I–II, n=36; for Stage III–IV, n=25).*p<0.05.

A fundamental role of Notch signaling is in regulation of cell fate and behavior during embryogenesis (11). Notch signaling can become spatially restricted to a subset of cells in a developing tissue by asymmetric cell division or lateral inhibition (27). We investigated if Notch4 and Nodal expression is restricted to a subpopulation of aggressive melanoma cells. Confocal microscopy performed on C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cultures with Nodal (green) and Notch4 (red) antibodies (Fig.2C; Supplemental Fig.1) revealed that protein expression was indeed limited to a subpopulation of cells. We detected Nodal protein in approximately one-third of cells (39%±6% [C8161]; 29%±11% [MV3]; 29%±7% [SK-MEL-28]; Fig.2D). Notch4 protein was detected in up to one quarter of cells (25%±3% [C8161]; 18%±8% [MV3]; 18%±2% [SK-MEL-28]). Importantly, Nodal and Notch4 co-expression was also observed in a subset of cells (10%±3% [C8161]; 10%±8% [MV3]; 11%±2% [SK-MEL-28]), suggesting that cross-talk between these pathways occurs in cell subpopulations. In all cell lines, staining was predominant in the cytoplasm, with some membrane and occasional nuclear localization. Furthermore, some cells exhibited Nodal and Notch4 co-localization (yellow; arrowheads in Fig.2C and Supplemental Fig.1A–C).

We also performed immunohistochemistry on serial sections of a human melanoma tissue array to address whether Notch4 and Nodal expression was correlated with melanoma progression. Results indicated that strong immunostaining for Nodal and Notch4 was significantly more common in advanced stage (Stage III–IV) melanomas as compared to early stage (Stage I–II) melanomas (64% for Nodal and 40% for Notch4 in Stage III–IV [n=25] versus 36% for Nodal and 17% for Notch4 in Stage I–II [n=36]; p<0.05; Fig.2E; Supplemental Fig.2; Supplemental Table 3). Altogether, these data indicate a specific Notch4 and Nodal correlation in aggressive melanoma cell subpopulations, and in advanced stage melanomas.

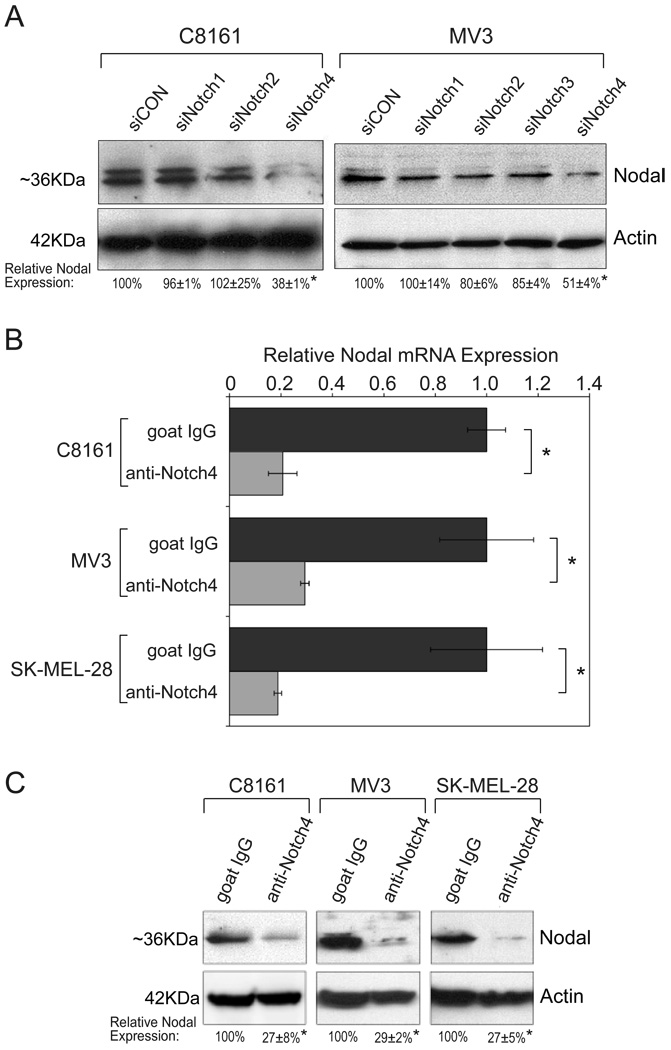

Notch4 activity is required for Nodal expression in aggressive melanoma cell lines

To test the hypothesis that Notch4 signaling modulates Nodal expression, C8161 and MV3 cells were transfected with small-inhibitory RNAs (siRNAs) to each Notch receptor, and Nodal expression assessed by Western blotting (Fig.3A). siRNA specificity was verified by real-time PCR (Supplemental Table 4) and confirmed for Notch4 by Western blotting (Supplemental Fig.3). Cells transfected with siRNA to Notch1 (siNotch1), Notch2 (siNotch2), Notch3 (siNotch3; shown for MV3), or negative control (siCON) had little effect on Nodal expression in either cell line (Fig.3A). In contrast, siRNA to Notch4 (siNotch4) significantly reduced expression of Nodal protein (62±1% [C8161]; 49±4% [MV3]; p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Notch4 signaling regulates expression of Nodal. A) Transfection of C8161 (left) and MV3(right) cells with siRNA to Notch1 (siNotch1), Notch2 (siNotch2), Notch3 (siNotch3), Notch4 (siNotch4), or a negative control (siCON), followed by Western blotting for Nodal protein. Actin was a loading control. Relative Nodal expression was determined by densitometry (n=3). B–C) C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells were treated with anti-human Notch4 neutralizing antibody or IgG. RNA was analyzed by real-time PCR for expression of Nodal mRNA (B). Protein lysates were analyzed for Nodal and Actin (C), and relative Nodal expression evaluated by densitometry (n=3).*p<0.05.

In addition, Notch4 activity in C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells was antagonized with a previously characterized anti-human Notch4 neutralizing antibody (24), and Nodal expression examined by real-time PCR (Fig.3B) and Western blotting (Fig.3C). Treatment with anti-Notch4 antibody dramatically reduced Nodal transcripts in all cell lines compared with IgG-treated control cultures (Fig.3B; p<0.05). Similarly, Nodal protein levels were highly down-regulated in anti-Notch4 treated cultures (73±8% [C8161]; 71±2% [MV3]; 73±5% [SK-MEL-28]; p<0.05; Fig.3C).

To demonstrate anti-human Notch4 antibody specificity, C8161 cells were transfected with a Notch4-ICD expression vector, then antagonized with the anti-Notch4 antibody or goat IgG (Supplemental Fig.4A). IgG-exposed untransfected and Notch4-ICD transfected cells expressed typical Nodal protein levels. However, untransfected cells exposed to anti-Notch4 antibody showed practically no Nodal protein, while antibody treated cells expressing Notch4-ICD recovered expression of Nodal protein. This finding suggests that Notch4-ICD regulates some Nodal expression. Further validation of the Notch4-Nodal relationship was discovered in poorly aggressive UACC1273 cells (that typically lack Nodal) transfected with Notch4-ICD, which resulted in Nodal upregulation (Supplemental Fig.4B). Collectively, these data strongly support a role for Notch4 activity in upregulating Nodal in melanoma cell lines.

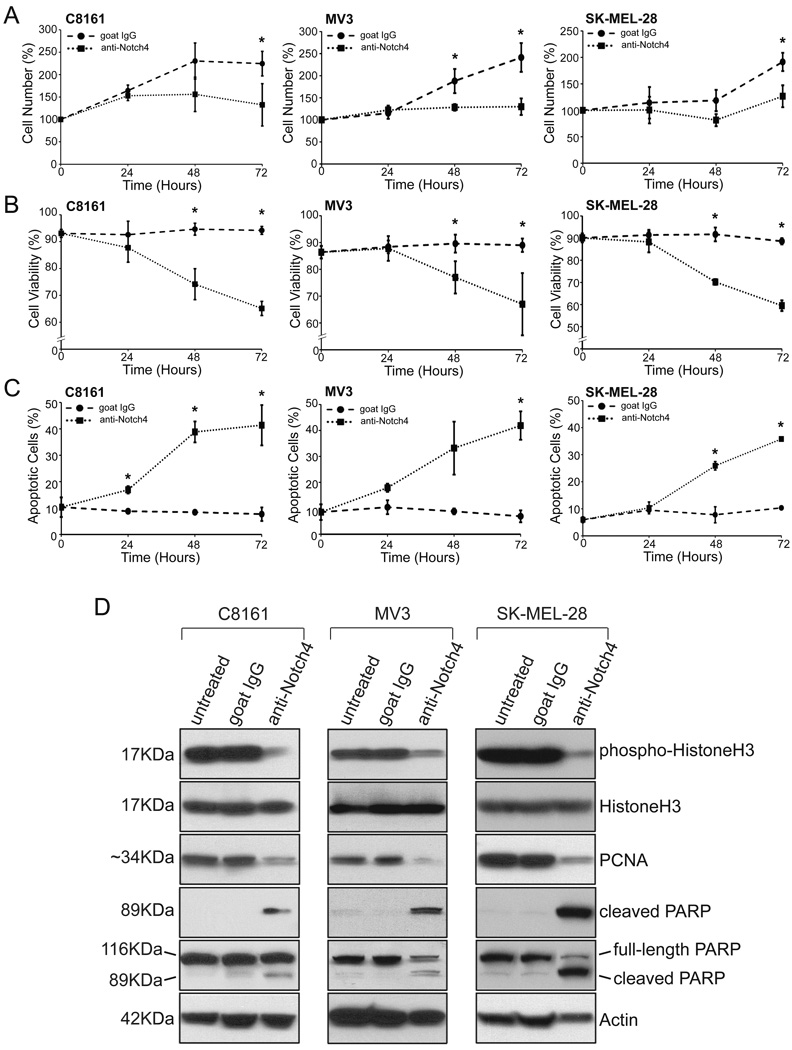

Notch4 inhibition impacts cellular proliferation and apoptosis

To determine the effects of inhibiting Notch4 signaling on cellular growth, C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells treated with anti-Notch4 antibody or IgG were analyzed for cell population size (Fig.4A), cell viability (Fig.4B), and apoptosis (Fig.4C) by flow cytometry. Compared with IgG cell populations that typically doubled over the culture period, anti-Notch4 treated cells showed little proliferative increase and remained significantly lower than control cell population size (Fig.4A; p<0.05). In contrast, control cells exhibited consistently high viability, while anti-Notch4 treated cells displayed a significant viability decline (Fig.4B; p<0.05). Furthermore, the percentage of apoptotic cells remained constantly low in controls, but dramatically increased in anti-Notch4 treated cultures (Fig.4C; p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of Notch4 activity limits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells were treated with anti-human Notch4 antibody or IgG. A–C) At 24-hour time points, cells were assayed for cell number (A), viability (B), and apoptosis (C) by flow cytometry. Cell number is shown as a percentage of the initial population, while viability and apoptosis is represented as a percentage of total cells. Plots represent the mean of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (+/−SD);*p<0.05. D) Western blot analyses of HistoneH3 phosphorylation and PCNA expression (proliferation), and PARP cleavage (apoptosis) in C8161, MV3, and SK-MEL-28 cells. Actin was a loading control. Membranes were stripped between antibody detections. Western blots are representative of three experiments. Abbreviations: PCNA, Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen; PARP, Poly ADP-Ribosome Polymerase.

To complement this approach, the same three cell lines were antibody treated and evaluated for markers of proliferation (HistoneH3 phosphorylation and Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) expression) and apoptosis (Poly ADP-Ribosome Polymerase (PARP) cleavage) by Western blotting (Fig.4D). Phospho-HistoneH3 was detected in untreated and IgG-treated cells, but was dramatically reduced in anti-Notch4 treated cells, despite similar total HistoneH3 levels. PCNA expression was also reduced in anti-Notch4 treated cells compared with untreated and IgG-treated cells. In contrast, cleaved PARP was detected in anti-Notch4 treated cultures, but not in untreated or IgG treated cultures, while full-length PARP expression levels were similar or reduced in anti-Notch4 treated cells. Collectively, these findings indicate that Notch4 activity modulates cell proliferation and survival in aggressive melanoma cell lines.

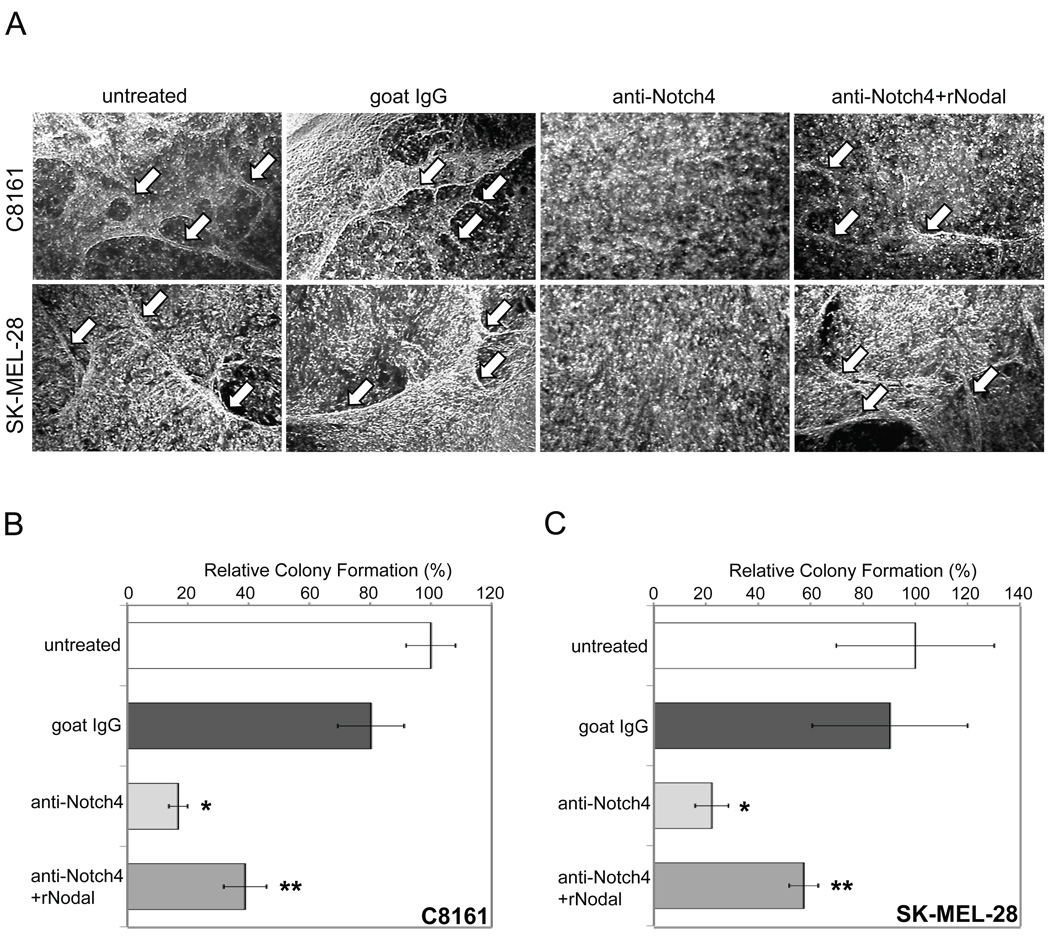

Inhibition of Notch4 activity impairs vasculogenic mimicry and diminishes clonogenicity in vitro in a Nodal-dependent manner

We next addressed the role of Notch4 in regulating melanoma cell behavior. C8161 and other aggressive melanoma cells typically engage in vasculogenic mimicry when grown on 3D-collagen matrix (25, 28–30). Notch4 is expressed in endothelial cells, and functions in vascular formation and remodeling, as well as in tumor angiogenesis (9, 31–33). Considering the relationship between tumor angiogenesis (recruitment of new vessels into a tumor from existing vessels) and tumor vasculogenic mimicry (de novo formation of vascular-like networks by non-endothelial tumor cells), we reasoned that Notch4 may also participate in vasculogenic mimicry. The ability of C8161 and SK-MEL-28 cells to form vascular-like network structures without Notch4 activity was evaluated in vitro (Fig.5A). Compared with untreated (left) and IgG cultures (middle-left) where vascular-like networks formed (white arrows), anti-Notch4 antibody treatment severely impaired vascular-like network formation (middle-right). When cultures exposed to anti-Notch4 antibodies were treated with recombinant human Nodal protein, vascular-like network formation was restored (right). Recombinant Nodal also rescued VE-cadherin and endogenous Nodal expression down-regulated by Notch4 inhibition in C8161cells (Supplemental Fig.5A). Anti-Notch4 treated C8161 cells expressing Notch4-ICD also recovered Nodal and VE-cadherin protein expression (Supplemental Fig.5B). These data indicate that Notch4 regulation of vasculogenic mimicry is likely Nodal-dependent.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of Notch4 signaling blocks vasculogenic mimicry and anchorage independent growth in vitro in a Nodal-dependent manner. A) C8161 and SK-MEL-28 cells were seeded on 3D-collagen gel matrix and left untreated or treated with IgG, anti-Notch4 antibody, or anti-Notch4 antibody plus recombinant human Nodal (rNodal). White arrows indicate vascular-like network formation in untreated (far-left), IgG-treated (center-left), and anti-Notch4+rNodal-treated cultures (far-right). Original magnification 100X. B–C) Relative colony formation in C8161 (B) and SK-MEL-28 (C) cells cultured on soft agar following pretreatment with IgG or anti-Notch4 antibody with or without rNodal. Graph indicates macroscopic colonies as a percentage of control (+/− SD).*Significant difference from untreated/IgG-treated cultures (p<0.05);**significant difference from anti-Notch4 treated cultures (p<0.05). Graphs depict one representative experiment of three.

The tumorigenic potential of Notch4 function was evaluated via in vitro clonogenic assays. C8161 and SK-MEL-28 cells pretreated with anti-Notch4 antibody formed significantly fewer macroscopic colonies in soft agar compared with untreated or IgG-pretreated cells (Fig.5B–C; p<0.05). Notably, cells pretreated with anti-Notch4 antibody plus recombinant Nodal protein recovered some anchorage-independent growth capacity (p<0.05). Altogether, these data suggest that Notch4 functions to promote the tumorigenic phenotype in vitro, likely in part through regulation of Nodal expression.

DISCUSSION

The aberrant re-expression of Nodal in metastatic melanoma cells critically regulates cellular plasticity and aggressiveness (2, 3). Here, we identify a decisive link between Notch4 and Nodal in multiple aggressive melanoma cell lines that modulates the aggressive tumorigenic phenotype in vitro, in part through regulation of Nodal. We describe expression of Nodal and Notch4 protein in advanced stage human melanomas, which further validates a recent study of Nodal in melanocytic lesions (8). Our observations are confirmed by earlier work in mouse xenograft models (3, 34). In one study, a synthetic gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI), that indiscriminately inhibits Notch receptor activation, significantly diminished in vivo melanoma tumor volume in nude mice injected with C8161 cells (34). Whether the observed reduction in tumor growth was coincident with down-regulation of Nodal was not evaluated, but would offer an interesting explanation for the observed effect considering that Nodal has also previously been shown to regulate in vivo melanoma tumor formation in xenografted nude mice (3). Considering the evidence presented in our current study, we speculate that inhibition of Notch4 activity might similarly affect in vivo melanoma tumor formation.

We describe the co-expression of Nodal and Notch4 in subpopulations of aggressive melanoma cells and the requirement of Notch4 for Nodal expression. We also show that Nodal expression is upregulated by exogenously expressed Notch4-ICD. Together these data provide strong indication that Notch4 lies upstream of Nodal expression in, at least, the aggressive tumor cell lines studied herein. While, by immunofluorescence microscopy, some cells express both Notch4 and Nodal, the observation that select cells express one protein but not the other is likely indicative of the dynamic nature of this cancer cell population. Considering that Nodal can function in a paracrine fashion, protein observed in some cells may reflect uptake from the microenvironment rather than intracellular production. Nodal expression is maintained on a feed-forward loop, so Notch4 signaling may be required for initial Nodal expression in a cell but then be dispensable for its maintenance. Notch4 expression independent of Nodal may simply reflect early-stage signaling before convergence on the Nodal gene. However, it is possible that other factors also contribute to the regulation of Nodal.

Notch4 signaling is required for cell proliferation and survival in aggressive melanoma cells, and also modulates cellular plasticity and tumorigenic growth in vitro. Of significance, some phenotypic effects can be attributed to Notch4 regulation of the Nodal gene, as treatment with recombinant human Nodal rescues vasculogenic mimicry and anchorage-independent growth in vitro. However, recombinant human Nodal was unable to rescue cell growth in flow cytometry assays (data not shown), perhaps due to the shorter length of these experiments relative to other assays or because Notch4 function in cell growth is independent of Nodal.

As both the Notch and Nodal pathways are involved in stem and progenitor cell maintenance (35–38), we speculate that the subpopulation of cells expressing both Notch4 and Nodal may retain special properties such as enhanced cellular plasticity. Certainly, Notch4 activity regulates plasticity required for vasculogenic mimicry and anchorage-independent growth, though whether this plasticity is driven by a subpopulation of cells is not clear. One recent study specifically linked Notch4 activity to a breast cancer stem cell (BCSC) subpopulation capable of in vivo tumor initiation, despite other Notch receptors in these cells (39). That study described higher Notch4 activity than Notch1 activity in the BCSC subpopulation. Targeting Notch4 expression more effectively reduced the BCSC subpopulation and inhibited in vivo tumor formation than targeting Notch1 expression, suggesting, at least in breast cancer, that only specific Notch receptors promote cancer stem cell phenotypes. This may also hold significance for melanoma.

No role for Notch4 signaling has previously been described in melanoma, though other studies have linked Notch1 with melanoma disease progression and the transformation of melanocytes or early-stage melanoma cells to a more aggressive phenotype (5, 40–42). In some contexts, such as in embryonic development and in MMTV-mediated mammary gland tumor formation, Notch receptors have common functions (32, 43–45). However, Notch receptors have structural differences (Notch4 lacks TAD and NCR domains near the C-terminus and some epidermal-growth factor repeats near the N-terminus) that may be significant (9, 10) and studies have shown functional diversity among the Notch receptors (46–48). The present study indicates an independent function for Notch4 in regulating the Nodal gene in melanoma. Other work illustrates that Notch4 functions uniquely in breast cancer (39). Recently, Pinnix et al demonstrated increased Notch4 mRNA in melanoma cell lines and patient tissue lesions, compared with cultured melanocytes (5). However, inconsistent with our study, they observed similar levels of Notch4 mRNA in c81-61 (poorly aggressive) and C8161 (aggressive) cells. It is possible that “late passage” c81-61 cells utilized by Pinnix et al, as opposed to early passage c81-61 cells used in our study, have acquired some aggressive phenotypic markers (including Notch4 expression) consistent with genetic and phenotypic drift commonly seen with long-term in vitro culture conditions (49, 50). It is likely that molecular cross-talk between Notch and Nodal in melanoma is complex, as we fully appreciate that our own study examined only six human melanoma cell lines with respect to this relationship. It will be important for subsequent studies to extend our findings in additional cell lines and learn whether other Notch receptors can regulate Nodal expression.

Notch4 is involved in vessel patterning and remodeling during development (32, 33) and adulthood (9), and participates in tumor angiogenesis (31) and vasculogenic mimicry (as described herein). Based upon our validation of Nodal and Notch4 co-expression in advanced stage disease, targeting Notch4 in melanoma may offer an attractive two-hit therapeutic strategy; by impairing tumor cell plasticity, and limiting tumor microcirculation and growth. Understanding regulatory mechanisms that promote the aggressive phenotype, such as the Notch4-Nodal relationship, may provide useful exploratory avenues for melanoma prevention and treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Awards U54CA143869, R37CA59702, and R01CA121205 from the National Cancer Institute (M.J.C. Hendrix), MOP89714 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (L.M. Postovit), and Eisenberg Research Scholar Fund (L. Strizzi).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: Commercial research grant from Acceleron Pharma (M.J.C. Hendrix); Patent to target Nodal (M.J.C. Hendrix, E.A. Seftor, L.M. Postovit)

REFERENCES

- 1.Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Kasemeier-Kulesa J, Kulesa PM, Postovit LM. Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:246–255. doi: 10.1038/nrc2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA, et al. Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4329–4334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, et al. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 2006;12:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massi D, Tarantini F, Franchi A, et al. Evidence for differential expression of Notch receptors and their ligands in melanocytic nevi and cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:246–254. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinnix CC, Lee JT, Liu ZJ, et al. Active Notch1 confers a transformed phenotype to primary human melanocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5312–5320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schier AF. Nodal signaling in vertebrate development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:589–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.041603.094522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papageorgiou I, Nicholls PK, Wang F, et al. Expression of nodal signalling components in cycling human endometrium and in endometrial cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:122. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu L, Harms PW, Pouryazdanparast P, Kim DS, Ma L, Fullen DR. Expression of the embryonic morphogen Nodal in cutaneous melanocytic lesions. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1209–1214. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uyttendaele H, Marazzi G, Wu G, Yan Q, Sassoon D, Kitajewski J. Notch4/int-3, a mammary proto-oncogene, is an endothelial cell-specific mammalian Notch gene. Development. 1996;122:2251–2259. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allenspach EJ, Maillard I, Aster JC, Pear WS. Notch signaling in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:466–476. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.5.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolos V, Grego-Bessa J, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:339–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriyama M, Osawa M, Mak SS, et al. Notch signaling via Hes1 transcription factor maintains survival of melanoblasts and melanocyte stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:333–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schouwey K, Delmas V, Larue L, et al. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors influence progressive hair graying in a dose-dependent manner. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:282–289. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of Notch in tumorigenesis: oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:756–767. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borggrefe T, Oswald F. The Notch signaling pathway: transcriptional regulation at Notch target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1631–1646. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8668-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan J, Norris DP, Robertson EJ. Nodal activity in the node governs left-right asymmetry. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2339–2344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1016202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettenhausen B, Hrabe de Angelis M, Simon D, Guenet JL, Gossler A. Transient and restricted expression during mouse embryogenesis of Dll1, a murine gene closely related to Drosophila Delta. Development. 1995;121:2407–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams R, Lendahl U, Lardelli M. Complementary and combinatorial patterns of Notch gene family expression during early mouse development. Mech Dev. 1995;53:357–368. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs LT, Iwai N, Nonaka S, et al. Notch signaling regulates left-right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1207–1212. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raya A, Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-Esteban C, et al. Notch activity induces Nodal expression and mediates the establishment of left-right asymmetry in vertebrate embryos. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1213–1218. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postovit LM, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ. Targeting Nodal in malignant melanoma cells. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:497–505. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strizzi L, Hardy KM, Seftor EA, et al. Development and cancer: at the crossroads of Nodal and Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7131–7134. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeuchi JK, Lickert H, Bisgrove BW, et al. Baf60c is a nuclear Notch signaling component required for the establishment of left-right asymmetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608118104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dontu G, Jackson KW, McNicholas E, Kawamura MJ, Abdallah WM, Wicha MS. Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R605–R615. doi: 10.1186/bcr920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniotis AJ, Folberg R, Hess A, et al. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:739–752. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoek K, Rimm DL, Williams KR, et al. Expression profiling reveals novel pathways in the transformation of melanocytes to melanomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5270–5282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Meltzer PS, et al. Expression and functional significance of VE-cadherin in aggressive human melanoma cells: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8018–8023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131209798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seftor RE, Seftor EA, Koshikawa N, et al. Cooperative interactions of laminin 5 gamma2 chain, matrix metalloproteinase-2, and membrane type-1-matrix/metalloproteinase are required for mimicry of embryonic vasculogenesis by aggressive melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6322–6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess AR, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates membrane Type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and MMP-2 activity during melanoma cell vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4757–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hainaud P, Contreres JO, Villemain A, et al. The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor-Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch4-ephrin B2 cascade in tumor vessel remodeling and endothelial cell functions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8501–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uyttendaele H, Ho J, Rossant J, Kitajewski J. Vascular patterning defects associated with expression of activated Notch4 in embryonic endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5643–5648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091584598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin JZ, Stennett L, Bacon P, et al. p53-independent NOXA induction overcomes apoptotic resistance of malignant melanomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:895–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hitoshi S, Alexson T, Tropepe V, et al. Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:846–858. doi: 10.1101/gad.975202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallier L, Reynolds D, Pedersen RA. Nodal inhibits differentiation of human embryonic stem cells along the neuroectodermal default pathway. Dev Biol. 2004;275:403–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James D, Levine AJ, Besser D, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. TGFbeta/activin/nodal signaling is necessary for the maintenance of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Development. 2005;132:1273–1282. doi: 10.1242/dev.01706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, et al. Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:823–826. doi: 10.1038/nature04940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison H, Farnie G, Howell SJ, et al. Regulation of breast cancer stem cell activity by signaling through the Notch4 receptor. Cancer Res. 2010;70:709–718. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balint K, Xiao M, Pinnix CC, et al. Activation of Notch1 signaling is required for beta-catenin-mediated human primary melanoma progression. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3166–3176. doi: 10.1172/JCI25001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedogni B, Warneke JA, Nickoloff BJ, Giaccia AJ, Powell MB. Notch1 is an effector of Akt and hypoxia in melanoma development. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3660–3670. doi: 10.1172/JCI36157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu ZJ, Xiao M, Balint K, et al. Notch1 signaling promotes primary melanoma progression by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathways and up-regulating N-cadherin expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4182–4190. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitamoto T, Takahashi K, Takimoto H, et al. Functional redundancy of the Notch gene family during mouse embryogenesis: analysis of Notch gene expression in Notch3-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:1154–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jhappan C, Gallahan D, Stahle C, et al. Expression of an activated Notch-related int-3 transgene interferes with cell differentiation and induces neoplastic transformation in mammary and salivary glands. Genes Dev. 1992;6:345–355. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu C, Dievart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P. Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:973–990. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu K, Chiba S, Saito T, Kumano K, Hamada Y, Hirai H. Functional diversity among Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:775–779. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y, Lowther W, Kato K, et al. Notch4 intracellular domain binding to Smad3 and inhibition of the TGF-beta signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:5365–5374. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan X, Mikolaenko I, Elhassan I, et al. Notch1 and notch2 have opposite effects on embryonal brain tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7787–7793. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neri A, Nicolson GL. Phenotypic drift of metastatic and cell-surface properties of mammary adenocarcinoma cell clones during growth in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1981;28:731–738. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910280612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welch DR, Krizman DB, Nicolson GL. Multiple phenotypic divergence of mammary adenocarcinoma cell clones. I. In vitro and in vivo properties. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1984;2:333–355. doi: 10.1007/BF00135172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.