Abstract

Dietary restraint is a prospective risk factor for the development of binge eating and bulimia nervosa. Although many women engage in dietary restraint, relatively few develop binge eating. Dietary restraint may only increase susceptibility for binge eating in individuals who are at genetic risk. Specifically, dietary restraint may be a behavioral “exposure” factor that activates genetic predispositions for binge eating. We investigated this possibility in 1,678 young adolescent and adult same-sex female twins from the Minnesota Twin Family Study and the Michigan State University Twin Registry. Twin moderation models were used to examine whether levels of dietary restraint moderate genetic and environmental influences on binge eating. Results indicated that genetic and non-shared environmental factors for binge eating increased at higher levels of dietary restraint. Importantly, these effects were present after controlling for age, body mass index, and genetic and environmental overlap among dietary restraint and binge eating. Results suggest that dietary restraint may be most important for individuals at genetic risk for binge eating, and the combination of these factors could enhance individual differences in risk for binge eating.

Keywords: binge eating, dietary restraint, gene-environment interactions, twins

Eating disorders are debilitating conditions that affect 0.5–3% of adolescent and adult women (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000). One symptom of eating disorders that cuts across virtually all eating disorder diagnostic categories is binge eating. Binge eating is defined as consuming an amount of food over a discrete period larger than what most individuals would eat and experiencing a sense of loss of control while bingeing (APA, 2000). Importantly, regular binge eating is present in adolescent and adult community populations (prevalence rates: 1.8–5%) (Hay, 2003; Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Jones, Bennett, Olmsted, Lawson, & Rodin, 2001) and is associated with reduced quality of life and greater psychopathology (Hay, 2003). Thus, it is critical to understand the etiology of binge eating.

Extant cross-sectional and longitudinal data suggest that dietary restraint (i.e., the intent and/or attempt to restrict caloric intake) increases risk for binge eating (Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwann, Kraemer, & Agras, 2004). Stice and colleagues have shown that dietary restraint prospectively predicts the onset of binge eating (Stice & Agras, 1998; Stice, Killen, Hayward, & Taylor, 1998b), as well as the growth of these symptoms (Stice, 2001) after 1–2 years. Other longitudinal studies also report that dietary restraint is a potent risk factor for the development of binge eating and bulimia nervosa (BN) among adolescent females (e.g., Neumark-Staizner, Wall, Haines, Story, & Eisenberg, 2007; Patton, Selzer, Coffey, Carlin & Wolfe, 1999).

Dietary restraint may lead to binge eating in numerous ways. One possibility is dieting results in reduced caloric intake that leads to binge eating via physiological deprivation and the body’s defense of its weight set point (Nisbett, 1972). In support of this, animal research demonstrates that cycles of caloric restriction result in binge-like consumption of palatable food (Hagan, Chandler, Wauford, Rybak, & Oswald, 2003; Placidi et al., 2004). The presence of these associations in rodents underscores the likely importance of physiological deprivation in eliciting binge eating in humans. Indeed, a recent longitudinal study associated fasting (i.e., no eating for 24 hours for weight control) with the onset of binge eating over a 1–5 year follow-up (Stice, Davis, Miller, & Marti, 2008).

In addition to physiological mechanisms, cognitive factors may be important for binge eating in restrained eaters (Polivy & Herman, 1985; Wardle, 1980; Wardle, 1981). Because dieting is a cognitively mediated activity (e.g., deciding not to eat even when hungry), dieters can become susceptible to disinhibited eating when their cognitive control is disrupted by the presence of diet-breaking foods, alcohol, and/or negative mood (e.g., Herman & Polivy, 1975; Polivy & Herman, 1976; Ruderman & Wilson, 1979). This phenomenon is frequently termed the “abstinence violation effect” (Marlatt & Gordon, 1984), as even small diet “failures” (i.e., eating one cookie) are interpreted as an inability to maintain control, and overeating ensues (Wilson, 1993).

Finally, dietary restraint may represent an “intent to diet” rather than actual caloric restriction. A series of studies suggest scores on self-report measures of dietary restraint may not correspond with objectively measured reductions in food intake (Stice, Fisher, & Lowe, 2004; Stice, Cooper, Schoeller, Tappe, & Lowe, 2007). Thus, individuals who have a desire to diet may be at increased risk for binge eating even in the absence of decreased caloric intake.

It remains unclear how physiological deprivation, cognitive control, and intent to diet contribute to restraint-binge eating relationships. Nonetheless, dietary restraint is clearly significant for the development of binge eating. However, many women engage in dietary restraint, but few develop binge eating symptoms. Dieting and dietary restraint are common with roughly 20–23% of adolescent and adult women reporting these behaviors (Jones et al., 2001; Paeratakul, York-Crowe, Williamson, Ryan, & Bray, 2002; Rand & Kuldau, 1991). By contrast, estimates of current, regular binge eating range from 1.8–5.0% in women, depending on definitions used (Hay, 2003; Hudson et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2001).

Differences in the prevalence of dietary restraint/dieting versus binge eating highlight the fact that although dietary restraint increases risk for binge eating, it does not inevitably lead to these behaviors (Wilson, 1993). Dietary restraint therefore interacts with other etiological factors for binge eating, and one possible set of factors are genetic risk factors (Klump & Culbert, 2007). Binge eating and BN have a substantial genetic component, with approximately 50% of the variance accounted for by genetic influences (Bulik, Sullivan, & Kendler, 1998; Klump, McGue, & Iacono, 2002; Sullivan, Bulik, & Kendler, 1998; Wade, Treloar, & Martin, 2008). Dietary restraint and genetic risk may interact in the development of binge eating, such that engaging in dietary restraint may activate genetic influences on binge eating in vulnerable individuals. In this case, dietary restraint would be more likely to lead to binge eating in genetically at risk individuals compared to those with low genetic risk.

The above scenario is an example of a gene-environment interaction. Gene-environment interactions occur when: 1) an environmental stressor is more likely to lead to negative outcomes in the presence of genetic risk; or 2) genetic susceptibility is activated in the presence of an environmental pathogen (Moffitt, Caspi, & Rutter, 2005). Environmental “exposures” in gene-environment interactions are broadly defined (e.g., cannabis use (Caspi et al., 2005), stressful life events (Caspi et al., 2003)), and dietary restraint could be conceptualized as a behavioral exposure factor for binge eating.

To date, only one study has examined gene-environment interactions for binge eating and dietary restraint. This study used a molecular genetic design (i.e., examination of associations between allelic variations in candidate genes and a phenotype) to investigate whether dietary restraint moderates associations between serotonin genes (i.e., serotonin-2a receptor gene and serotonin transporter gene) and binge eating in a non-clinical sample of women (Racine, Culbert, Larson, & Klump, 2009). No significant interactions between serotonin genes and dietary restraint were detected for binge eating. This study had a relatively small sample for a molecular study and only investigated two candidate genes. Thus, significant associations may emerge in larger samples examining multiple SNPs or candidate genes within the serotonin and other important biological systems (e.g., dopamine, brain-derived neurotrophic factor).

The early focus on molecular genetic studies may have been premature, as we have not obtained evidence that significant gene × dietary restraint interactions exist for binge eating. A powerful approach for establishing the presence of such interactions is the twin study. Twin studies are able to quantify genetic and environmental effects on a phenotype and, more recently, determine if an exposure variable significantly influences the magnitude of these effects (Purcell, 2002). Because twin studies examine the aggregate of all genetic influences on a phenotype, this method can determine whether evidence for gene-environment interactions exists at the latent genetic level. If twin analyses are significant, efforts can be directed toward isolating specific genes/biological systems that may underlie effects. If twin analyses fail to support the presence of gene-dietary restraint interactions, efforts can be directed toward other moderators or phenotypes, as documented gene-environment interactions have the potential for greatest payoff in molecular studies.

The current study aimed to investigate the presence of gene-dietary restraint interactions for binge eating in a large sample of adolescent and young adult same-sex female twins. We tested whether dietary restraint significantly moderates genetic and environmental influences on binge eating. We hypothesized the heritability of binge eating would increase with increasing levels of dietary restraint, given that engaging in dietary restraint may enhance existing genetic vulnerabilities towards binge eating. We controlled for body mass index (BMI) in all analyses, as BMI has been associated with both dietary restraint and binge eating (Fitzgibbon et al., 1998) and could contribute to any gene-environment interactions observed in this study.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 1,678 same-sex female twins (MZ = 1028, DZ = 650) between the ages of 11 and 29 (M = 17.87, SD = 3.30) from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS; Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999) and the Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR; Klump & Burt, 2006). The MTFS is a longitudinal, population-based study of same-sex twins born in the state of Minnesota. The MTFS sample is representative of the population from which it is drawn in terms of racial/ethnic background and other key demographic variables (i.e., 98% Caucasian; Holdcraft & Iacono, 2004). Detailed information about recruitment strategy, demographics, and assessment procedures has been outlined elsewhere (Iacono et al., 1999). The MTFS participants for the current study were from the first follow-up assessment and included 1,262 (MZ = 798, DZ = 464) female twins ages 13–23 (M = 17.57, SD = 3.00).

The remaining data came from the MSUTR, a relatively new registry of twins born in lower Michigan. Similar to the MTFS, the MSUTR is now a population-based twin registry, as all twins are recruited through birth records in collaboration with the Michigan Department of Community Health. However, most twins in the current sample (62.5%) served as the pilot sample of MSTUR twins who were recruited through newspaper advertisements, flyers, and university registrar offices prior to obtaining approval for birth record use. Nonetheless, MSUTR twins have been shown to be demographically representative of individuals from the recruitment region in terms of racial and ethnic background (i.e., 83% Caucasian; Culbert, Breedlove, Burt, & Klump, 2008). For complete details of recruitment and assessment procedures, see Klump & Burt (2006). The MSUTR sample included 416 twins (MZ = 230, DZ = 186) ages 11–29 years (M = 18.78, SD = 3.95).

Previous work suggests genetic influences on disordered eating are nominal in pre-pubertal girls, but increase substantially during middle puberty (Culbert, Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Klump, 2009; Klump, McGue & Iacono, 2003). For this reason, MTFS and MSUTR twins were only included in the current study if they were in mid-puberty or beyond (as determined using scores on the Pubertal Development Scale, see Culbert et al. (2009) and Klump et al. (2003)). Because there are no significant differences in the magnitude of genetic effects from middle puberty into late adolescence (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2003) and young adulthood (Klump, Burt, Spanos, McGue, Iacono, & Wade, in press), our inclusion of twins that span these ages should not unduly influence results. Nonetheless, we used age regressed scores to ensure that age differences do not account for findings (see Statistical Analyses).

Measures

Zygosity Determination

Similar to other large-scale twin registries (e.g., Kendler, Heath, Neale, Kessler, & Eaves, 1992; Lichtenstein et al., 2002) physical similarity questionnaires were used as the primary determinant of zygosity in both the MTFS and MSUTR. The same questionnaire was used to establish zygosity in the MTFS sample and the adult MSUTR twins (Lykken, Bouchard, McGue, & Tellegen, 1990). For the MSUTR adolescent twins, a similar but slightly modified questionnaire was used in which mothers reported on the physical similarity of their twins. Both the original (Lykken et al., 1990) and the modified (Peeters, Van Gestel, Vlietinck, Derom, & Derom, 1998) versions are over 95% accurate when compared to genotyping. MSUTR zygosity discrepancies (~32% of female twins) were resolved by having the principal investigators of the MSUTR review physical similarity scores and twin photographs (Klump & Burt, 2006). The MTFS confirmed questionnaire responses of zygosity by considering staff evaluations of physical similarity and an algorithm that examines finger print ridge counts as well as ponderal and cephalic indices. When the three MTFS measures of zygosity were discrepant (~33% of female twins), a serological analysis of blood group antigens and protein polymorphisms was performed to determine correct zygosity (Iacono et al., 1999).

Binge Eating

Binge eating was assessed using the Binge Eating subscale from the Minnesota Eating Behaviors Survey (MEBS; Klump, McGue & Iacono, 2000; von Ranson, Klump, Iacono & McGue, 2005)1. The MEBS is a 30 item self-report survey, and the Binge Eating subscale is comprised of 7 true-false items that assess thoughts of binge eating (e.g., “I think a lot about overeating (eating a really large amount of food)”) and engagement in binge eating behaviors (e.g., “Sometimes I eat lots and lots of food and feel like I can’t stop”). The MEBS was designed for use with children as young as 10 years and is thus an appropriate measure to capture the construct of binge eating across the age range of the current sample.

The psychometric properties of the MEBS have been examined across young adolescent and adult females. Internal consistency for the Binge Eating subscale is acceptable in the current sample (see Table 1) and previous samples across a range of ages (von Ranson et al., 2005). Concurrent validity of the MEBS Binge Eating subscale is also well established, as it correlates with overall measures of disordered eating (e.g., Eating Disorder Examination- Questionnaire (EDE-Q) Total Score; r = .41–44; von Ranson et al., 2005) and related measures of binge eating (e.g., Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire-Emotional Eating; r = .69; Racine et al., 2009). Criterion validity has also been established, as women with BN score significantly higher on the MEBS Binge Eating subscale than unaffected control women (von Ranson et al., 2005). Finally, our measure of binge eating correlates with other internalizing phenotypes. Within the MSTUR sample, the MEBS Binge Eating subscale exhibits moderate correlations with measures of depression (r’s = .39–.50) and anxiety (r’s = .35–.47) that are similar to correlations observed for other binge eating measures (Mitchell & Mazzeo, 2004; Spoor et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Measure | Alpha | Mean (SD) | Range | % above clinical cut-off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEBS Binge Eating | .71 | 1.15 (1.52) | 0–7 | 8.4 % |

| EDE-Q Restraint | .82 | .91 (1.22) | 0–6 | 10.0 % |

MEBS = Minnesota Eating Behaviors Survey; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; SD = standard deviation.

Dietary Restraint

Dietary restraint was assessed using the Restraint subscale of the EDE-Q (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). The EDE-Q is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that has been adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). The EDE-Q Restraint subscale assesses dietary restraint (i.e., the tendency to restrict food intake and avoid meals/high-calorie foods) as well as attempts to obey rigid rules for dieting (e.g., “Have you gone for long periods of time (8 hours or more) without eating anything in order to influence your shape or weight?”) over the past 28 days. Each of the 5 restraint items are rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from “No Days” to “Every Day”.

The EDE-Q Restraint scale has been used extensively with non-clinical samples (e.g., Jansen et al., 2008; Ross & Wade, 2004) and demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties within these populations. Excellent internal consistency exists for the Restraint scale in our sample (see Table 1) and other non-clinical samples (Luce & Crowther, 1999). In addition, high two-week test-retest reliability (r = .81; Luce & Crowther, 1999) has been reported in a non-clinical sample of females. Good concurrent validity between the EDE-Q and the EDE Restraint subscales has been demonstrated within community samples (r = .71; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen & Beumont, 2004). Finally, criterion validity of the EDE-Q restraint subscale is established, as women with sub-threshold and threshold eating disorders score significantly higher than healthy control women (Mond et al., 2004).

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI (Weight (in kilograms)/Height (in meters) squared) was assessed. In the MTFS, height was measured with an anthropometer, and weight was measured on a platform scale with a beam and moveable weights. In the MSUTR, height was measured with a wall mounted ruler, and weight was measured with a digital scale.

Statistical Analyses

Binge eating scores were log transformed (log10 (X + 1)) prior to analysis to account for kurtosis and positive skew. Age and BMI were regressed out of log-transformed binge eating scores to ensure results are not due to these confounds. Specifically, a regression in which age and BMI were entered as the independent variables and binge eating was entered as the dependent variable was performed, and standardized residual binge eating scores (after partialing out age and BMI) were saved for use in subsequent analyses. Standardized residuals were used to facilitate interpretation of unstandardized parameter estimates (see below).

We used twin gene-environment interaction models (Purcell, 2002) to quantify the degree of additive genetic (A; the additive effects of multiple genes), shared environmental (C; factors that make members of a twin pair similar to one another), and non-shared environmental (E; factors that make members of a twin pair different from one another) influences on binge eating and the effects of dietary restraint on these parameter estimates. Within these models, additive genetic effects are suggested if the MZ twin correlation is approximately twice the DZ twin correlation, shared environmental effects are inferred if MZ and DZ twin correlations are approximately equal, and non-shared environmental effects (and measurement error) are implied if the MZ twin correlation is less than 1.0. Gene-environment interactions are indicated if A, C, and E estimates differ at each level of the moderator, such that the heritability and/or environmentality of binge eating varies by levels of dietary restraint. Twin moderation models simultaneously model all of these effects and provide a powerful tool for examining gene-environment interactions.

Model fitting was conducted using full information maximum-likelihood (FIML) raw data techniques with Mx statistical software (Neale, 1997). Raw data techniques treat missing data as missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1987), and allow for the retention of twin pairs in which one twin in a pair has missing data. In the current sample, 9.3% and 15.6% of participants had missing scores on binge eating or dietary restraint, respectively, and only 2% had missing data for both measures. Importantly, results from structural equation models using FIML techniques appear to be unbiased at this level of missing data (10–15%; Ender & Bandalos, 2001).

We used the modified ‘gene-environment interaction in the presence of gene-environment correlation’ model to control for genetic overlap between dietary restraint and binge eating. This model was necessary given results from preliminary bivariate, Cholesky decomposition models. These bivariate models examine overlap in genetic and environmental influences for binge eating and dietary restraint by estimating genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental correlations between the two phenotypes (Neale & Cardon, 1992). A significant (albeit, modest) genetic correlation was observed between dietary restraint and binge eating (ra = .22 (95% CI: .02, .38)), indicating that the two phenotypes share a small but significant proportion of genetic effects. Our use of modified twin moderation models ensured that findings were not unduly influenced by these correlations, as significant moderator-dependent variable genetic correlations can artificially increase estimates of gene-environment interactions (see Purcell, 2002).

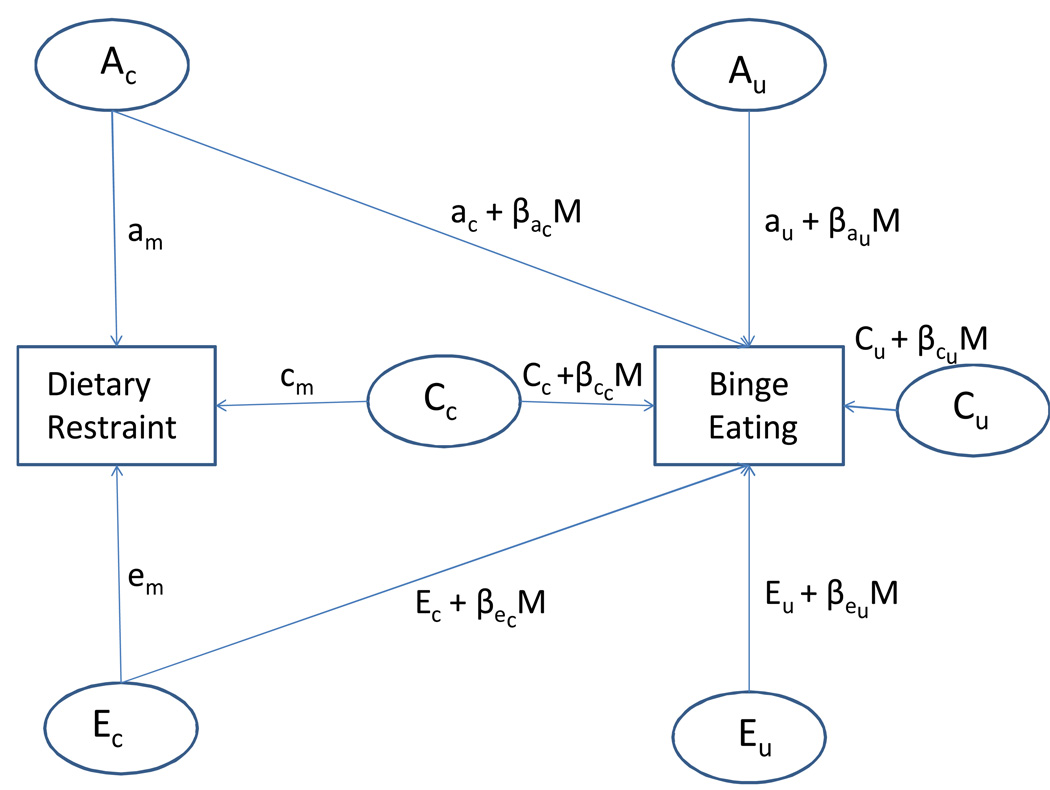

The full moderation model is presented in Figure 1. The model is essentially an extension of the bivariate Cholesky decomposition model where the variance within and covariance between the moderator (i.e., dietary restraint) and dependent variable (i.e., binge eating) is decomposed into additive genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental effects (Purcell, 2002). However, the moderator models also include a β term that indicates whether a measured variable M (i.e., dietary restraint) significantly moderates genetic and environmental influences on an outcome variable (i.e., binge eating). M represents the level of dietary restraint for each individual twin in the sample, and the A, C, and E effects on binge eating for each individual twin will be a linear function of their level of dietary restraint.

Figure 1. Path Diagram for the Genetic, Shared Environment, and Non-shared Environment Components of the Twin Moderation Model Accounting for Genetic Correlations.

Ac = genetic effects common to dietary restraint and binge eating; Au = genetic effects unique to binge eating; Cc = shared environment effects common to dietary restraint and binge eating; Cu = shared environment effects unique to binge eating; Ec = non-shared environment effects common to dietary restraint and binge eating; Eu = non-shared environment effects unique to binge eating; am = influence of Ac on dietary restraint; cm = influence of Cc on dietary restraint; em = influence of Ec on dietary restraint; ac = main effect of Ac on binge eating; βac = interaction between dietary restraint and Ac; cc = main effect of Cc on binge eating; βcc = interaction between dietary restraint and Cc; ec = main effect of Ec on binge eating; βec = interaction between dietary restraint and Ec; au = main effect of Au on binge eating; βau = interaction between dietary restraint and Au; cu = main effect of Cu on binge eating; βcu = interaction between dietary restraint and Cu; ecu= main effect of Eu on binge eating; βeu = interaction between dietary restraint and Eu.

In order to separate gene-environment correlation and gene-environment interaction effects within the model, genetic effects on the dependent variable are partitioned into those that are shared with the moderator (Ac) and those that are unique to the dependent variable (Au) (see Figure 1). Both genetic paths can then interact with the moderator, as represented by the moderation coefficients βac and βau. Therefore, after partialing out the genetic effects on binge eating that are shared with the genetic effects on dietary restraint (Ac), we can determine whether dietary restraint significantly moderates genetic influences unique to binge eating (Au) by examining whether βau is significant. This framework can similarly be used to examine moderation of shared and non-shared environmental influences on binge eating that do not overlap with those for dietary restraint (βcu and βeu, respectively; see Figure 1).

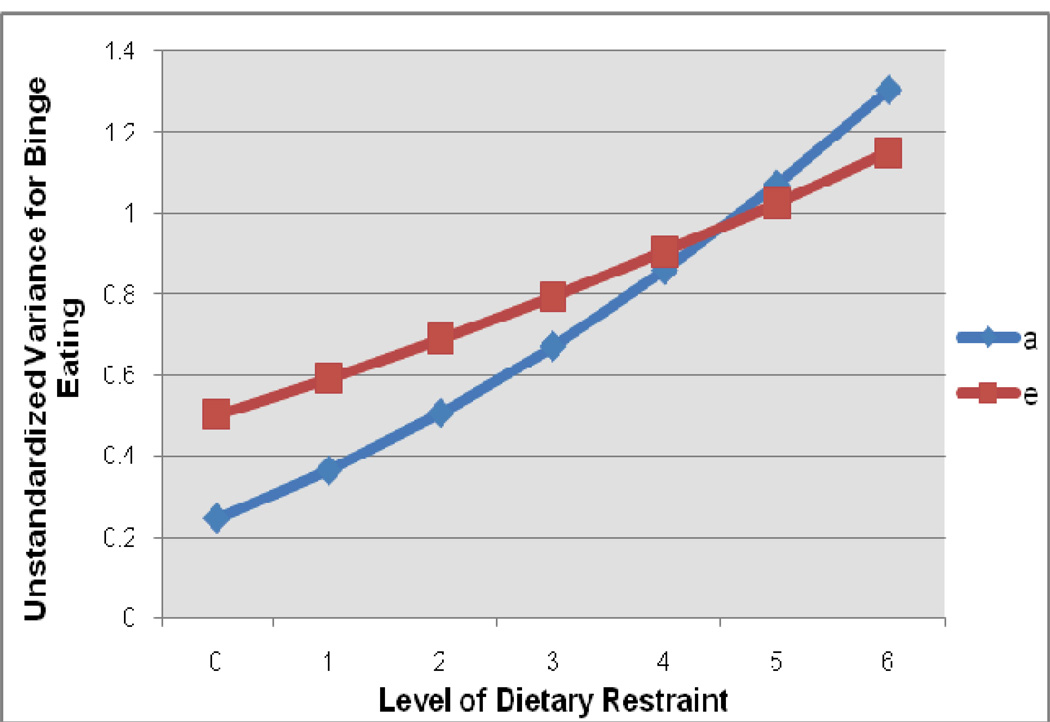

We tested a series of nested models to evaluate the importance of genetic and environmental moderation effects. The full model contained all main and interaction effects. Because the focus of analyses was moderation of genetic and environmental influences unique to binge eating, we then fit sub-models in which we dropped the unique moderators for genetic (βau), shared environmental (βcu), and non-shared environmental (βeu) effects one at a time. Model fit was examined using the change in the minimized value of minus twice the log likelihood (−2lnL) and the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). When comparing nested models, the change in −2lnL yields a likelihood chi-square test that is used to determine significance of sub-models. AIC evaluates model fit relative to model parsimony and will be smaller in the best fitting models. The following equations were then used to calculate the genetic and environmental variance components that are unique to binge eating for each level of the moderator in the best fitting model: variancea = (Au + βau (dietary restraint))2; variancec = (Cu + βcu (dietary restraint))2; variancee = (Eu + βeu (dietary restraint))2. Notably, unstandardized parameter estimates from this model are presented in tables and figures as they more accurately depict absolute changes in variance by level of the moderator rather than standardized estimates, which represent changes in the proportion of variance explained by A, C, and E (Purcell, 2002).

Before conducting any model-fitting analyses, we confirmed that MSUTR and MTFS samples could be combined. Despite modest twin registry differences in levels of dietary restraint (MSUTR: M = 1.12, SD = 1.28; MTFS: M = .84, SD = 1.20) and binge eating (MSUTR: M = 1.49; SD = 1.72 MTFS: M = 1.05; SD = 1.43) after controlling for age (d = .15 for dietary restraint, d = .16 for binge eating), variance differences were minimal (all p’s > .05). Importantly, we fit univariate, twin constraint models to confirm that there were not etiologic differences between the registries. In these models, we compared the fit of fully unconstrained models (i.e., A, C, and E estimates were free to vary across the two twin samples) to fully constrained models (i.e., A, C, and E estimates were constrained to be equal across the two twin samples) in order to determine if genetic and environmental influences on dietary restraint and binge eating differed for MTFS and MSUTR participants. The fully constrained model provided the best fit to the data for both dietary restraint (Δχ2 = 1.85, Δdf = 3, p > .05) and binge eating (Δχ2 = 5.59, Δdf = 3, p > .05), suggesting no significant differences in genetic and environmental influences on these phenotypes in the two samples. Consequently, MTFS and MSUTR samples were combined for all subsequent analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics for binge eating and dietary restraint are presented in Table 1. Inspection of means, ranges, and, in particular, standard deviations of binge eating and restraint scores suggested that, although means for both variables were low, there was sufficient variability in these constructs (Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, 2006; von Ranson et al., 2005). Moreover, 8.4 % of twins scored above the clinical cut-off for MEBS Binge Eating (score = 4; von Ranson et al., 2005), and 10% of twins scored above the clinical cut-off for EDE-Q Restraint (score = 3; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). This indicates the presence of significant clinical pathology in our sample. The Pearson correlation between dietary restraint and binge eating was positive and significant (r = .27, p < .001), corroborating previous research (e.g., Racine et al., 2009; Spoor et al., 2006) suggesting that higher levels of dietary restraint are associated with greater binge eating.

Results from moderator models are presented in Table 2 and 3 and Figure 2. As shown in Table 2, the best fitting model was one in which there was no moderation of the shared environmental effects unique to binge eating. This model has the lowest AIC value, and dropping the shared environmental moderation coefficient (βcu) did not provide a significantly worse fit to the data compared to the full moderation model (as evidenced by a non-significant chi-square difference test). In contrast, nested model analyses indicated that dropping the genetic and non-shared environmental unique moderation coefficients (βau and βeu, respectively) provided significantly worse fits to the data compared to the full model (as indicated by significant chi-square difference tests). Overall, results suggest dietary restraint moderates both the genetic and non-shared environmental influences unique to binge eating.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics for Moderation Models.

| Models | −2lnL | df | Δχ2 (Δdf) | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Moderation | 7632.54 | 2590 | -- | 2452.54 |

| Drop unique A mod (βau) | 7636.82 | 2591 | 4.28* (1) | 2454.82 |

| Drop unique C mod (βcu) | 7632.54 | 2591 | 0 (1) | 2450.54 |

| Drop unique E mod (βeu) | 7637.94 | 2591 | 5.40* (1) | 2455.94 |

Note. Mod = moderator; −2lnL = minus two times the log likelihood; df = degrees of freedom; Δχ2 = change in chi-square (−2lnL) from the full moderation model; AIC = Akaike Information Criteria;

p < .05.

The best-fitting model is noted in bolded text.

Table 3.

Unstandardized Path and Moderator Estimates for the Best-Fitting Twin Moderation Model

| Genetic (a) | Shared Environment (c) |

Non-shared Environment (e) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Estimates | |||

| Moderator (M) | .93 (.82, 1.00) | 0 (−.38, .38) | .82 (.76, .87) |

| Common to BE/DR (c) | .27 (.11, .42) | 0 (−.34, .34) | .23 (.10, .37) |

| Unique to BE (u) | .50 (.36, 59) | 0 (−.30, .30) | .71 (.65, .77) |

| Moderator Estimates | |||

| Common to BE/DR (βc) | −.06 (−.14, .02) | 0 (−.19, .19) | −.01 (−.08, .06) |

| Unique to BE (βu) | .11 (.01, .18) | -- | .06 (.01, .12) |

Note. BE = binge eating; DR = dietary restraint. All estimates are followed by 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Confidence intervals that do not overlap with zero index statistical significance at p < .05. Significant estimates are noted in bolded text.

Figure 2. Unstandardized Genetic and Non-Shared Environmental Variance Components that are Unique to Binge Eating at Different Levels of Dietary Restraint.

a = additive genetic effects; e = non-shared environmental effects. Level of dietary restraint corresponds to scores on the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire Restraint Scale, which range from 0–6.

Table 3 includes path and moderator estimates for the best fitting model. As hypothesized, the unique genetic moderation coefficient was positive and significant (i.e., the 95% confidence intervals did not include 0). Figure 2 depicts the increase in genetic influences unique to binge eating with increases in levels of dietary restraint. Examination of standardized estimates further corroborated these impressions, as the heritability of binge eating (after controlling for genetic influences shared with dietary restraint) was 33% at the lowest level and 53% at the highest level of dietary restraint.

Level of dietary restraint was also important in influencing the degree of non-shared environmental effects that are unique to binge eating. The moderation coefficient for the unique non-shared environmental effects on binge eating was positive and significant (see Table 3). As with genetic effects, non-shared environmental influences increased with increasing levels of dietary restraint (see Figure 2).2

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine whether dietary restraint significantly moderates genetic and environmental influences on binge eating. Findings supported our hypothesis that genetic influences on binge eating would increase with increasing levels of dietary restraint. In addition, moderation of non-shared environmental influences on binge eating was detected, where non-shared environmental influences on binge eating also increased at higher levels of dietary restraint. Importantly, both moderation effects were present after controlling for BMI, age, and genetic and environmental overlap between dietary restraint and binge eating.

This is the first study to report a significant gene-environment interaction for dietary restraint in risk for disordered eating, and only the second published study to investigate gene-environment interactions for any eating disorder phenotype. Currently, there is a relative lack of understanding of the complex genetic etiology of eating disorders. Moffitt and colleagues (2005) have argued that failure to identify risk genes for psychiatric disorders may be due to a lack of consideration of gene-environment interactions. The one former study to examine interactions between dietary restraint and genetic risk for binge eating failed to find significant interactions for two serotonin genes (Racine et al., 2009). Discrepant results between Racine et al. (2009) and the current study are unlikely due to measurement issues, as both studies used the MEBS Binge Eating scale and the EDE-Q Restraint scale. However, these studies differed in measurement of genetic risk, in that Racine et al. (2009) examined two genetic polymorphisms (i.e., serotonin-2a receptor T102C polymorphism, serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism) for binge eating, while the current study used a latent genetic factor that represents the aggregate of all genetic effects on binge eating. Our findings collectively indicate that gene-dietary restraint interactions are likely present for binge eating, but the two genes investigated thus far do not account for interactive effects. If replicated in future twin work, results support moving forward with molecular genetic studies investigating gene-dietary restraint interactions for binge eating. Such studies should take a broader approach by examining several candidate genes and wider genomic regions using methods such as genome-wide association studies. These larger-scale methods are needed as binge eating is influenced by multiple genes, each with a small effect (Kaye et al., 2004), and dietary restraint likely interacts with more than one genomic region.

It will also be important to elucidate the mechanisms by which dietary restraint may increase genetic effects for binge eating. One possibility is dietary restraint may enhance genetic differences in biological systems involved in food intake and body weight regulation (e.g., serotonin, ovarian hormones, brain-derived neurotrophic factor). Specifically, the biological effects of dieting/dietary restraint may be most pronounced in individuals with pre-existing genetic susceptibilities towards increased food intake/binge eating. However, dietary restraint may tap an ‘intent to diet’ rather than decreased caloric intake (Stice et al., 2004), and the biological consequences of an ‘intent to diet’ are unknown. In addition, biological factors are not the only potential explanation for gene-environment interaction effects. Dietary restraint could also interact with psychological factors such as negative affect or depression, given that these factors share phenotypic and genetic risk with binge eating (Klump et al., 2002). Consequently, future work is encouraged to examine biological and psychological mechanisms that could explain the effects of dietary restraint on genetic risk for binge eating.

Dietary restraint was also important in moderating non-shared environmental influences on binge eating. Moderation of non-shared environmental factors has two interpretations within twin models. First, dietary restraint could directly interact with risk factors unique to each twin (e.g., life events, involvement in weight-focused sports and/or peer groups), making co-twins dissimilar to each other and increasing non-shared environmental variance in binge eating. Second, non-shared environmental moderation may reflect the presence of gene × non-shared environment interactions (Purcell, 2002). Twin models partition gene × non-shared environment interactions into the E estimate, as non-shared environmental factors that interact with genetic risk will decrease twin similarity, regardless of zygosity, because these factors only affect one twin in a pair. An example would be if dietary restraint interacted with a non-shared environmental risk factor (e.g., participation in weight focused sports) that increased risk for binge eating in genetically predisposed individuals only. Taken together, dietary restraint is important for influencing non-shared environmental risk for binge eating and may do so directly or through its effects on genetic risk.

Notably, binge eating was influenced by genetic and non-shared environmental influences even when levels of dietary restraint were low, suggesting that dietary restraint may enhance rather than activate etiologic effects on binge eating. In other words, many factors in addition to dietary restraint contribute to the genetic and environmental diathesis for binge eating, and engaging in dietary restraint is not necessary for the presence of these influences. However, the combination of genetic/non-shared environmental risk and exposure to dietary restraint may be particularly detrimental and appears to enhance individual differences in risk for binge eating. This accentuation of genetic and non-shared environmental influences may help explain differences in the prevalence of dietary restraint versus binge eating. Binge eating may be more likely to occur in the presence of dietary restraint if genetic and non-shared environmental risk factors are also present. Longitudinal studies using genetically informative designs are needed to investigate whether genetic/non-shared environmental risk plus dietary restraint prospectively predicts the development of binge eating.

Although our findings significantly contribute to an understanding of the etiology of binge eating, we must acknowledge several limitations. First, our choice of instruments to assess binge eating and dietary restraint was limited to those included in both the MTFS and the MSUTR. Self-report measures of binge eating have been criticized for overestimating the frequency of binge eating behaviors (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Black & Wilson, 1996). However, our measure of binge eating has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in previous community samples (von Ranson et al., 2005; von Ranson, Cassin, Bramfield, & Fung, 2007). Moreover, the MEBS was developed for use with children and adolescents and is thus one of the few acceptable measures of binge eating given the age range of our sample. Finally, we had appropriate variability with regards to binge eating scores, with over 8% of our sample scoring at or above the clinical cut-off. Although future studies would benefit from examining changes in the heritability of binge eating using interviews in addition to self-report questionnaires, our findings are an important first step in the investigation of gene-environment interactions for binge eating.

Second, we examined a non-clinical sample of twins rather than those with diagnosable eating disorders. This was necessary to increase statistical power for twin moderation analyses and to ensure that we had ample variability in levels of dietary restraint to examine moderating effects. Most women with BN would be expected to have high levels of dietary restraint, making it difficult to examine etiologic moderation by dietary restraint in a clinical sample. However, future research should determine whether gene-dietary restraint interactions observed in this study predict the eventual development of BN.

Finally, our data were cross-sectional rather than longitudinal in nature. Although dietary restraint has been prospectively associated with binge eating in previous studies (Jacobi et al., 2004), we cannot infer direction of causation in the current study. Future longitudinal research is needed to determine whether early measurements of dietary restraint moderate genetic and environmental influences on later assessments of binge eating.

If our results are replicated with longitudinal data, findings will have the potential to inform prevention of binge eating and BN. Prevention programs have begun to target women at high risk for eating disorders by selecting those who exhibit high levels of body image disturbances and/or dietary restraint (Chase & Cullen, 2001; Stice & Shaw, 2004). These programs may be enhanced by adding another level of screening and selecting individuals with a family history of binge eating or an associated eating disorder (e.g., BN, BED). Given that engaging in dietary restraint appears to increase genetic risk for binge eating, individuals with this combination of risk factors (e.g., high dietary restraint and family history of eating disorders or binge eating) are not only at greater environmental risk, but also greater genetic risk for binge eating. This additional screening may increase cost effectiveness and ensure that prevention programs are directed towards those most in need of services.

In conclusion, we report significant moderation of genetic and non-shared environmental risk for binge eating by levels of dietary restraint in a sample of female twins. This is the first study to report a significant genetic-dietary restraint interaction, and only the second to examine gene-environment interactions for disordered eating phenotypes. Findings suggest that engaging in dietary restraint may enhance genetic predispositions and individual differences in genetic risk for binge eating. Our results contribute to a growing understanding of the biological bases of disordered eating and, more importantly, how behavioral exposure factors may modify genetic risk for eating pathology.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MDR-96630) awarded to Ms. Racine, the National Institute of Mental Health (1R21-MH070542-01) and the Michigan State University Intramural Grants Program (71-IRGP-4831) awarded to Dr. Klump, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA-05147) and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA-09367) awarded to Drs. Iacono and McGue.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

Parts of this manuscript were presented at the Behavior Genetics Association meeting, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 18–June 20, 2009, and the Eating Disorders Research Society meeting, Brooklyn, New York, September 24–26, 2009.

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey Survey (MEBS; previously known as the Minnesota Eating Disorder Inventory (M-EDI)) was adapted and reproduced by special permission of Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Eating Disorder Inventory (collectively, EDI and EDI-2) by Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy (1983) Copyright 1983 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction of the MEBS is prohibited without prior permission from Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Rathouz et al. (2008) have recently questioned the accuracy of the ‘gene-environment interaction in the presence of gene-environment correlation’ model, asserting that it could lead to spurious detection of gene-environment interactions. In order to confirm that our results were not due to model misspecification, we also ran the ‘straight gene-environment interaction’ model (Purcell, 2002) that does not control for gene-environment correlations and is therefore unaffected by these misspecification problems. Results remained unchanged (i.e., dietary restraint significantly moderated genetic and non-shared environmental influences on binge eating), which was not surprising, given that Rathouz et al. (2008) found that misspecifications were less likely to occur when genetic correlations were low (as they were in the current study, i.e., ra = .22). These supplementary analyses indicate that our findings are not unduly influenced by our use of the ‘gene-environment interaction in the presence of the gene-environment correlation’ model.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Black CMD, Wilson GT. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview versus questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1996;20:43–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199607)20:1<43::AID-EAT5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Heritability of binge-eating and broadly defined bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:1210–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, McClay J, Murray R, Harrington HL, et al. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-o-methyltransferase gene: Longitudinal evidence of a gene × environment interaction. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1117–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase AK. Eating disorder prevention: An intervention for “at-risk” college women. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2001;62:1568B. [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KC, Breedlove SM, Burt SA, Klump KL. Prenatal hormone exposure and risk for eating disorders: A comparison of opposite-sex and same-sex twins. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:329–336. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KC, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia and bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper P. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. In: Fairburn C, Wilson G, editors. The Eating Disorder Examination (12th edition) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon ML, Spring B, Avellone ME, Blackman LR, Pingitore R, Stolley MR. Correlates of binge eating in Hispanic, Black, and White women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:43–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199807)24:1<43::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MM, Chandler PC, Wauford PK, Rybak RJ, Oswald KD. The role of palatable food and hunger as trigger factors in an animal model of stress induced binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34:183–197. doi: 10.1002/eat.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay PJ. Quality of life and bulimic eating disorder behaviors: Findings from a community-based sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:434–442. doi: 10.1002/eat.10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, Polivy J. Anxiety, restraint, and eating behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1975;84:666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft LC, Iacono WG. Cross-generational effects on gender differences in psychoactive drug use and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A, Havermans R, Nederkoorn C, Roefs A. Jolly fat or sad fat?: Subtyping non-eating disordered overweight and obesity along an affect dimension. Appetite. 2008;51:635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Bennett S, Olmsted MP, Lawson ML, Rodin G. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviours in teenaged girls: A school-based study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;165:547–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye WH, Devlin B, Barbarich N, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Bacanu S, et al. Genetic analysis of bulimia nervosa: Methods and sample description. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:556–570. doi: 10.1002/eat.10271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. A population-based twin study of alcoholism in women. Journal of American Medical Association. 1992;268:1877–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): Genetic, environmental and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:971–977. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA, Spanos A, McGue M, Iacono WG, Wade T. Genetic and environmental influences on key eating disorder symptoms: Developmental differences from childhood through middle adulthood for weight and shape concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.20772. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Culbert KM. Molecular genetic studies of eating disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Age differences in genetic and environmental influences on eating attitudes and behaviors in preadolescent and adolescent female twins. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:239–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic relationships between personality and eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:380–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Differential heritability of eating attitudes and behaviors in prepubertal versus pubertal twins. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:287–292. doi: 10.1002/eat.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, De Faire U, Floderus B, Svartengren M, Svedberg P, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry: A unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2002;252:184–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RTA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York, NY: Wiley Publishing; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:349–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<349::aid-eat15>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT, Bouchard TJ, McGue M, Tellegen A. The Minnesota Twin Family Registry: Some initial findings. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae: Twin Research. 1990;39:35–70. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000005572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention: Introduction and overview of the model. Addiction. 1984;79:261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE. Binge eating and psychological distress in ethnically diverse undergraduate men and women. Eating Behaviors. 2004;5:157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:473–481. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for young adult women. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J, Hay P, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC. Mx: Statistical Modeling. 4th edition. Richmond, VA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for the genetic studies of twins and families. Norwell, MA: Kluwer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE. Hunger, obesity, and the ventromedial hypothalamus. Psychological Review. 1972;79:433–453. doi: 10.1037/h0033519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J, Story M, Eisenberg ME. Why does dieting predict weight gain in adolescents? Findings from Project EAT-II: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: Population based cohort study over 3 years. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:765–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7186.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeratakul S, York-Crowe EE, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Americans on diet: Results from the 1994–1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102:1247–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters H, Van Gestel S, Vlietinck R, Derom C, Derom R. Validation of a telephone zygosity questionnaire in twins of known zygosity. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:159–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1021416112215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placidi RJ, Chandler PC, Oswald KD, Maldonado C, Wauford PK, Boggiano MM. Stress and hunger alter the anorectic efficacy of fluoxetine in binge-eating rats with a history of caloric restriction. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:328–341. doi: 10.1002/eat.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Effects of alcohol on eating behavior: Influence of mood and perceived intoxication. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and binging: A causal analysis. American Psychologist. 1985;40:193–201. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance components models for gene-environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Research. 2002;5:554–571. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine SE, Culbert KM, Larson CL, Klump KL. The possible influence of impulsivity and dietary restraint on associations between serotonin genes and binge eating. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand CSW, Kuldau JM. Restrained eating (weight concerns) in the general population and among students. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1991;10:699–708. [Google Scholar]

- Rathouz PJ, Van Hulle CA, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID, Lahey BB. Specification, testing, and interpretation of gene-by-measured-environment interaction models in the presence of gene-environment correlation. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:301–315. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M, Wade TD. Shape and weight concern and self-esteem as mediators of externalized self-perception, dietary restraint, and uncontrolled eating. European Eating Disorders Review. 2004;12:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman AJ, Wilson GT. Weight, restraint, cognitions and counterregulation. Behaviour research and therapy. 1979;17:581–590. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoor STP, Stice E, Bekker MH, Van Strien T, Croon MA, Van Heck GL. Relations between dietary restraint, depressive symptoms, and binge eating: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:700–707. doi: 10.1002/eat.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:124–135. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Agras WS. Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Cooper JA, Schoeller DA, Tappe K, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of moderate-to long-term dietary restriction? Objective biological and behavioral data suggest not. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:449. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Davis K, Miller NP, Marti CN. Fasting increases risk for onset of binge eating and bulimic pathology: A 5-year prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:941–946. doi: 10.1037/a0013644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobstrusive observational data suggest not. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:51–59. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Age of onset for binge eating and purging during late adolescence: A 4-year survival analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998b;107:671–675. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H. Eating disorder prevention programs: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bullentin. 2004;130:206–227. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Bulik CM, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of binging and vomiting. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;173:75–79. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ranson KM, Cassin SE, Bramfield TD, Fung TS. Psychometric properties of the Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey in Canadian university women. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2007;39:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- von Ranson KM, Klump KL, Iacono WG, McGue M. The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey: A brief measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:373–392. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade TD, Treloar S, Martin NG. Shared and unique risk factors between lifetime purging and objective binge eating: A twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1455–1464. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J. Dietary restraint and binge eating. Behavioral Analysis and Modification. 1980;4:201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Beinart H. Binge eating: A theoretical review. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1981;20:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1981.tb00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Relation of dieting and voluntary weight loss to psychological functioning and binge eating. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;119:727–730. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]