Abstract

Mu B is one of four proteins required for the strand transfer step of bacteriophage Mu DNA transposition and the only one where no high resolution structural data is available. Structural work on Mu B has been hampered primarily by solubility problems and its tendency to aggregate. We have overcome this problem by determination of the three-dimensional structure of the C-terminal domain of Mu B (B223–312) in 1.5 M NaCl using NMR spectroscopic methods. The structure of Mu B223–312 comprises four helices (backbone r.m.s.d. 0.46 Å) arranged in a loosely packed bundle and resembles that of the N-terminal region of the replication helicase, DnaB. This structural motif is likely to be involved in the inter-domainal regulation of ATPase activity for both Mu A and DnaB. The approach described here for structural determination in high salt may be generally applicable for proteins that do not crystallize and that are plagued by solubility problems at low ionic strength.

Keywords: DnaB/helicase/Mu B/structure/transposition

Introduction

DNA transposition is an important process that can mediate a variety of effects in living organisms. The mechanism whereby DNA sequences can move from one location to another requires a complex array of protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions. One of the best understood transposition systems is that of phage Mu (for reviews see Lavoie and Chaconas, 1995; Chaconas et al., 1996; Mizuuchi, 1997; Chaconas, 1999), which has served as a model system for a variety of transposons. In vivo, Mu integrates into the bacterial genome and replicates via transposition. The steps of the replicative pathway of Mu DNA transposition can be performed in vitro with purified proteins and DNA substrates, allowing for molecular dissection of this process. The strand transfer step of Mu transposition can be promoted by only four proteins: the phage-encoded Mu A and Mu B proteins and the host-specified accessory factors HU and IHF. In the presence of donor and target DNA substrates these components assemble into a series of higher-order nucleoprotein complexes (transpososomes), which mediate the reaction to generate the strand transferred product. This stable protein–DNA reaction intermediate is subsequently disassembled to facilitate DNA replication by host proteins (Jones and Nakai, 1997, 1999), resulting in the formation of the transposition end-product or cointegrate.

Structural information regarding three of the four proteins required for the strand transfer reaction has been reported and has aided understanding of the reaction mechanism. The host-encoded HU (Craigie and Mizuuchi, 1985; Vis et al., 1995; Lavoie et al., 1996) and IHF (Surette and Chaconas, 1989; Rice et al., 1996b; Rice, 1997) proteins are DNA flexers or architectural elements. These proteins overcome the intrinsic stiffness of DNA by introducing sharp bends, thereby facilitating interaction of proteins bound at distant sites along a DNA molecule. The donor and target DNA cleavage and the transesterification reactions are mediated by the three-domain, phage-encoded Mu A protein (Nakayama et al., 1987). The N-terminal domain of Mu A (domain I) has several sub-domains that are involved in sequence-specific DNA binding (Leung et al., 1989; Mizuuchi and Mizuuchi, 1989). A winged helix–turn–helix motif (Clubb et al., 1994, 1996) binds to the Mu transpositional enhancer region, and two other helix–turn–helix motifs (Clubb et al., 1997; Schumacher et al., 1997) bind to three similar sites at each end of the Mu genome. Domain II of Mu A comprises the catalytic core and resembles the catalytic domains of the related enzymes HIV and ASV integrase, as well as RNase H and the RuvC resolvase (Rice and Mizuuchi, 1995; Rice et al., 1996a). The C-terminal domain (III), which interacts with Mu B (Baker et al., 1991; Leung and Harshey, 1991; Wu and Chaconas, 1994) and may also be involved in substrate activation for catalysis (Wu and Chaconas, 1995; Naigamwalla et al., 1998), is flexible and lacks any regular tertiary structure (L.-H.Hung, G.Chaconas and G.S.Shaw, unpublished results).

While a great deal of structural and functional information is available for Mu A, much less is known about the second important transposition protein, Mu B. This protein is responsible for delivering the target DNA to the transposition complex (Craigie and Mizuuchi, 1987; Maxwell et al., 1987; Surette et al., 1987; Naigamwalla and Chaconas, 1997). Mu B also interacts with Mu A and can potentiate both the donor cleavage and strand transfer reactions (Baker et al., 1991; Surette and Chaconas, 1991; Surette et al., 1991). Consistent with this role, Mu B has been shown to bind non-specifically both single- and double-stranded DNA (Chaconas et al., 1985b; Maxwell et al., 1987), which can have a modulating effect on ATPase activity (Maxwell et al., 1987; Adzuma and Mizuuchi, 1991; Yamauchi and Baker, 1998). Interaction of Mu A with the Mu B–DNA complex stimulates ATP hydrolysis and release of the DNA substrate. Limited proteolysis of Mu B has identified two domains: a 23 kDa N-terminal domain (Mu B1–222) and a smaller 10 kDa C-terminal domain (Mu B223–312) (Teplow et al., 1988). The larger N-terminal domain is responsible for this ATPase activity as it contains a nucleotide binding motif and can bind ATP in the absence of the C-terminal domain (Chaconas, 1987; Teplow et al., 1988). The N-terminal domain also has a DNA binding activity that is required for target capture (Millner and Chaconas, 1998). The smaller C-terminal domain, Mu B223–312, has an additional DNA binding activity in vitro (Z.Wu and G.Chaconas, unpublished results). Truncated mutants of Mu B have shown that the C-terminal domain is necessary for both replicative transposition and integration of infecting Mu DNA; however, mutations removing only the last 18 amino acids confer a selective defect on replicative transposition (Chaconas et al., 1985a).

Structural studies of Mu B have been hampered primarily by the tendency of the protein and its domains to aggregate (Chaconas et al., 1985b; Teplow et al., 1988). Difficulties in obtaining consistent levels of overexpression and in purification of the protein (Millner and Chaconas, 1998) and its two domains have also slowed progress in structural determination. Moreover, sequence comparison has not revealed any related proteins with known structure and function and only a putative helix– turn–helix at the N-terminus (Miller et al., 1984) and a nucleotide binding fold in the N-terminal domain (Chaconas, 1987) have been noted. Attempts to crystallize the intact protein have been unsuccessful (W.F.Anderson and G.Chaconas, unpublished results). The only structural information to date comes from circular dichroism studies and indicates that the Mu B protein is largely α-helical (Chaconas et al., 1989). In this work we present the three-dimensional solution structure of the C-terminal domain of Mu B, the first detailed structural information about this important transposition protein. The structure reveals potential DNA binding surfaces and uncovers a novel structural motif shared with the replication helicase DnaB allowing further insight into the role of Mu B in transposition.

Results

Several factors have contributed to the lack of structural information on the Mu B transposition protein. The protein is exceedingly insoluble with a propensity to aggregate (Chaconas et al., 1985b). Moreover, fragments of the protein have been difficult to overexpress and to purify in the absence of contaminating degradation products (data not shown). To circumvent these problems the C-terminal domain of Mu B (Mu B223–312) was expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion under the control of a T7 promoter. The fusion protein was partially purified from inclusion bodies and Mu B223–312 released by thrombin cleavage. After further purification under denaturing conditions Mu B223–312 was refolded by slow removal of the denaturant by dialysis in a high salt buffer, as described previously for the intact Mu B protein (Chaconas et al., 1985b). Standard methods of GST purification utilizing a glutathione column could not be used due to the sensitivity of the GST fusion protein to proteases when isolated from the soluble fraction, and the inability of this fusion protein to refold in a homogeneous fashion when isolated from inclusion bodies.

Although more soluble than the complete protein, purified Mu B223–312 was not sufficiently soluble for NMR structural studies. The poor solubility was not improved using a wide variety of low ionic strength buffers (Na+, K+, Cl–, PO43–, SO42–, SCN–, CF3CO2–). Similarly, changes in solvent constituents [glycerol, trifluoroethanol, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)]; pH (6.0–8.5) or temperature (5–35°C) did not significantly improve solubility. In the presence of 500 mM NaCl at pH 6.8 the peptide was soluble to ∼3 mg/ml (0.3 mM); however, analytical ultracentrifugation and NMR experiments indicated that Mu B223–312 displayed characteristics consistent with an oligomeric state or equilibrium between multiple states under these conditions. In the presence of 1.5 M NaCl, however, Mu B was sufficiently soluble for NMR structural experiments (8 mg/ml, 0.8 mM). The resulting 1H-15N HSQC spectrum showed one N-H crosspeak per residue (Figure 1), an indication that a single form of the protein was present. The spectrum shows a tight grouping of 1H-15N crosspeaks and chemical shift indices indicative of a high α-helical content. These findings were consistent with previous circular dichroism studies showing that Mu B is a highly helical protein (Chaconas et al., 1989).

Fig. 1. 500 MHz 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of uniformly 15N-labeled Mu B223–312 in 20 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 M NaCl pH 6.8 at 25°C. Residue assignments are labelled according to sequence numbering for the intact protein. Side chain resonances are each connected with a line and labelled in parentheses. The box indicates the position of the E290 crosspeak that is visible at higher contour levels.

Solution structure of Mu B223–312

The solution structure of Mu B223–312 was determined in 1.5 M NaCl at pH 6.8 using heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. These unusually high ionic conditions have been used previously to aid structural studies of the 43-residue DNA binding protein from γδ resolvase (Liu et al., 1994; Pan et al., 1997). For Mu B223–312 the NMR assignment of 1H, 15N and 13C resonances was accomplished using a combination of 1H-1H TOCSY, 15N TOCSY-HSQC, 15N NOESY-HSQC, 15N HNHA and 13C NOESY-HSQC experiments. However, the high salt made the assignment more difficult due to unacceptably long pulse widths. For example, 1H pulse widths were 35% longer at 40% higher power levels. This resulted in poorer signal-to-noise and sample heating. For several experiments we were able to compensate for this by increasing the relaxation delay by as much as 100%. We attempted triple resonance experiments useful for intranuclear correlations and that involve either broadband decoupling (e.g. 13C TOCSY-HSQC) or simultaneous decoupling of two nuclei (e.g. HNCACB), and found that these were not practical due to the extent of the sample heating. Fortunately, a two-dimensional 1H-1H NOESY experiment proved invaluable in identifying nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) between the protons of the five aromatic residues (H272, H282, Y292, F297 and W246) and methyl protons from L274 and L291 that greatly facilitated the structure determination.

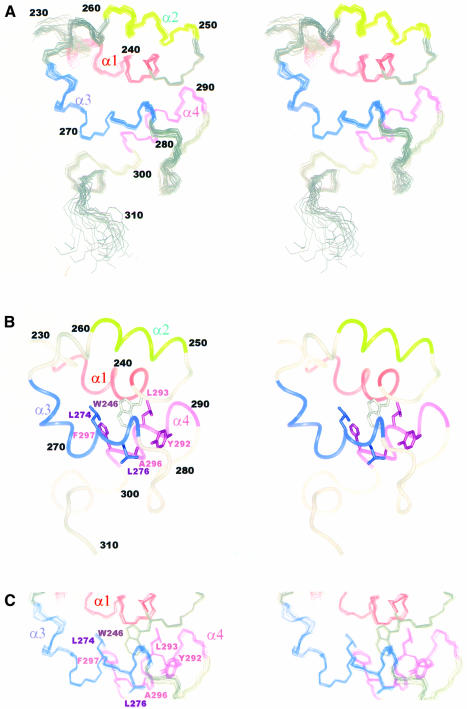

Calculations for the solution structure of Mu B223–312 utilized a total of 1047 NOE derived distance restraints and 55 dihedral angle restraints (Table I). From these data an ensemble of 20 acceptable structures was generated having no residual NOE violations >0.3 Å. The resulting solution structure of Mu B223–312 displayed r.m.s.d. values of 0.46 Å (backbone) and 0.86 Å (heavy atoms) in the well-folded region comprised of residues A230–S307 (Figure 2A). In contrast, the extreme N- and C-terminal residues, S223–T229 and L308–N312, respectively, showed no consistent secondary structure based upon a lack of both intermediate and long-range NOE restraints. These regions therefore appear to be flexible in solution. The folded region of Mu B223–312 consisted of three individually well-defined helices (backbone r.m.s.d. 0.33 Å) spanning the regions from K235 to A245 (α1), E251 to Q259 (α2) and N289 to R298 (α4) as shown in Figure 2B. Each of these helices produced a pattern of dNN, dαN(i,i+3) and dαβ(i,i+3) NOEs and chemical shifts consistent with an α-helical secondary structure. A fourth helix, A266–A278 (helix α3) was severely bent near residue L270 with the last three residues assuming more of a 310 helical conformation. Despite the bend, most of this helix retained the hydrogen bonding pattern, intermediate-range NOEs and φ/ψ backbone angles expected for a helical secondary structure.

Table I. Structural statistics for the ensemble of 20 accepted structures of Mu B223–312.

| Experimental restraints | |

| intraresidue NOEs | 202 |

| sequential NOEs (|i – j| = 1) | 329 |

| medium-range NOEs (1 < |i – j| ≤ 5) | 331 |

| long-range NOEs (|i – j| > 5) | 185 |

| total NOEs | 1047 |

| φ angles | 35 |

| χ-1 angles | 20 |

| total dihedral angles | 55 |

| R.m.s.ds from experimental constraint | |

| NOE restraints (Å) | 0.0374 ± 0.00096 |

| dihedral restraints (°) | 0.527 ± 0.085 |

| R.m.s.ds from ideal covalent geometry | |

| bonds (Å) | 0.00526 ± 0.00009 |

| angles (°) | 0.75677 ± 0.011 |

| impropers (°) | 1.894 ± 0.0033 |

| R.m.s.ds from average structure | |

| backbone (folded region 230–306) (Å) | 0.46 ± 0.09 |

| non-hydrogen (folded region 230–306) (Å) | 0.86 ± 0.07 |

| backbone (helices) (Å) | 0.33 ± 0.08 |

| non-hydrogen (helices) (Å) | 0.87 ± 0.07 |

| Procheck | |

| % residues in favoured or most favoured regions of Ramachandran plot (residues 230–306) | 89.2 |

Fig. 2. Solution structures of Mu B223–312 as determined from NMR data. (A) The backbone atoms (N, Cα, CO) for the family of 20 converged structures are shown using the superposition of helices α1 (K235–A245), α2 (E251–Q259), α3 (A266–A278) and α4 (N289–R298). The initial eight residues have no regular structure and were omitted from the figure. (B) Ribbon diagram of the ensemble average structure for the 20 structures in the same orientation as (A). Also shown are the side chains from residues W246 (α1), L275, L277 and A278 (α3) and Y292, L293, A296 and F297 (α4) that comprise the core region of the Mu B223–312 domain. (C) Details of the core region for Mu B223–312 showing the high degree of structural convergence for side chains of all 20 structures.

The four helices from the C-terminus of Mu B are arranged in a loosely packed four-helix bundle where helix α1 runs parallel to α3 (ω = 26°, residues L272–L277), and anti-parallel to helices α2 (ω = 137°) and α4 (ω = 124°). Helix α1 is the best packed helix of the bundle having mean interhelical distances of 11.0 Å from α2 and 12.5 Å from α3. Key contacts were identified in NOE spectra between helices α1 and α2 (A241–L256, D244, A245–E253), α1 and α3 (D238–L274, I242–L274) and α1 and α4 (V239–F297, I242, A245–L293), and contribute to the packing arrangement of these helices. Helices α3 and α4 pack with helix α1 via side chains from residues L274 and L276 (α3), Y292, L293, A296 and F297 (α4), many of which sandwich the side chain of W246 near the C-terminus of helix α1 to form the hydrophobic core of Mu B223–312 (Figure 2B and C). Long-range NOEs were also observed for residues A230–T234 just before helix α1 and residues I260–G265 in the loop between helices α2 and α3. The interhelical angles for Mu B223–312 agree well with those expected for classical four-helix bundles (Harris et al., 1994). However, helix α2 appears somewhat more loosely packed compared with the other helices, having several interactions with helix α1, but apparently lacking observable NOE interactions with the other helices.

Structural similarity of Mu B223–312 and the replication helicase DnaB

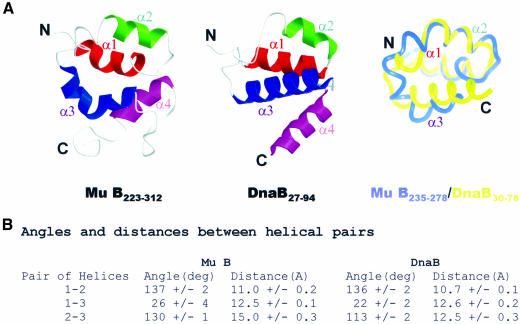

In order to obtain further insights into the biological role of Mu B223–312 we compared the solution structure of this domain with known structures in the DALI structural database (Holm and Sander, 1993). This approach was important because database searches for sequences similar to Mu B yielded no significant matches to other known protein folds or motifs. Comparison of the structure of Mu B223–312 with structures in the DALI database produced a significant structural match to the Escherichia coli replication helicase DnaB (Fass et al., 1999; Weigelt et al., 1999) (see Figure 3). Although the DALI algorithm matched the four helices of Mu B223–312 to the first four helices of DnaB (Z = 2.0), closer examination revealed that most of the similarities were in the first three helices. The comparison indicated that the orientation and arrangement of helices α1, α2 and α3 of Mu B223–312 were similar to helices α1, α2 and α3 from DnaB (Figure 3). In both cases helix α1 runs anti-parallel to helices α2 and α3. In DnaB an extended linker of six residues is found between helices α2 and α3. Mu B223–312 has a shorter linker separating helix α2 and the N-terminal portion of the bent helix, α3. The superposition reveals that helices α1 and α2 show the best alignment, each comprised of eleven and nine residues, respectively, and having a similar overall fold (backbone r.m.s.d. 1.62 Å). Furthermore, the interhelical angles between helices α1 and α2 in Mu B223–312 (Ωα1–α2 137°) and DnaB (Ωα1–α2 136°) are nearly identical (Figure 3B), as are the interhelical distances (11.0 compared with 10.7 Å). As described, the N-terminus of helix α3 from Mu B223–312 appears different from the analogous unstructured linker region of DnaB. This extra portion of helix in Mu B223–312 pushes the remainder of helix α3 away from helix α1, resulting in a more open conformation for Mu B223–312 (Ωα2–α3 130°) compared with DnaB (Ωα2–α3 113°). Despite this difference the interhelical angles for helices α1 and α3 are in excellent agreement (Mu B223–312 Ωα1–α3 26°, DnaB Ωα1–α3 22°), as are the distances between the helices (12.5 compared with 12.6 Å).

Fig. 3. Comparison of the folds of Mu B223–312 and the N-terminal region of E.coli DnaB. (A) The structures are shown side by side and superimposed as ribbon representations. Helices α1 and α2 were used to align the two proteins (backbone r.m.s.d. 1.62 Å). The resulting superposition of the two proteins was performed for residues K235–A278 of Mu B223–312. (B) Interhelical angles and distances between the first three helices of Mu B and DnaB.

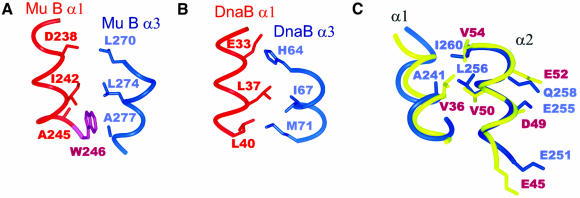

The structural alignment of Mu B223–312 and DnaB indicates that there should be packing similarities between the two proteins that give rise to the common arrangement of helices. The resulting sequence alignment (Figure 4) shows that some sequence similarities exist between the best structurally aligned helices, α1 and α2, in Mu B223–312 and E.coli DnaB (along with its eight closest homologues). In particular, residues at positions 3, 7, 8 and 11 of helix α1, positions 6, 7 and 10 in helix α2 and positions 1, 9 and 12 in helix α3 are conserved hydrophobes. Figure 5 shows that the conservation of these residues is reflected in the packing of helices α1 and α3. In Mu B223–312, positions 8 and 11 (I242, A245) from helix α1 pack with those in positions 5, 9 and 12 (L270, L274, A277) of helix α3 (Figure 5A). In DnaB the side chains from the same positions in helix α1 (L36, L39) pack against those in helix α3 (H64, I67 and M71) (Figure 5B). A major difference between the two proteins is the manner in which these helices accommodate small residue differences at the helix–helix interface. In DnaB two long-chain hydrophobic residues (L40, M71) engage at the interface near the C-terminus of helix α1. However, in Mu B223–312 the analogous residues (A245, A277) both have small side chains and are unable to contact each other. This is resolved through the intercalation of the indole ring of W246 between the methyl groups of A245 and A277.

Fig. 4. Multiple sequence alignment of helices α1, α2 and α3 from Mu B223–312 and the N-terminal region for DnaB from different organisms. The structural alignment in Figure 3 was used to align the sequences. Residues that are conserved between Mu B223–312 and DnaB are shaded. Residues that are identical in all DnaB proteins are boxed. Sequence numbering is indicated for Mu B (top) and E.coli DnaB (bottom).

Fig. 5. Packing similarity for helices α1 and α3 of Mu B223–312 (A) and the N-terminal region region of E.coli DnaB (B). (A) In Mu B223–312 the side chain of W246 from helix α1 inserts itself between the two helices to fortify the packing between A245 and A277. (B) In DnaB, the analogous packing arrangement shows the longer side chains of L40 and M71 at the helix–helix interface. (C) Superposition of helices α2 from Mu B223–312 (blue) and DnaB (gold) are shown using the same backbone alignment as in Figure 3. The side chains that form the negatively charged face are shown. Also indicated are the conserved residues V36, V50 and V54 in DnaB and A241, L256 and I260 in Mu B, which act to maintain the proper orientation of helix α2 with helices α1 and α3.

The positions of helices α1 and α2 in Mu B223–312 are maintained by interactions between residue A241 (α1) and L256 (α2). These two positions are highly conserved in DnaB where V36 and V50 occupy these sites. At the C-terminus of α2 a further conserved, branched hydrophobe is found, I260 in Mu B223–312 and V54 in DnaB. In both proteins this residue packs near the bend between helices α2 and α3, likely serving as an anchor to preserve the orientation of helix α2 with respect to helix α3. The orientation of this helix may be important in both proteins as helix α2 presents an exposed acidic face (E251, E255 and Q259 in Mu B223–312, E45, D49 and E53 in DnaB) that could participate in protein–protein interactions.

Identification of potential DNA binding sites

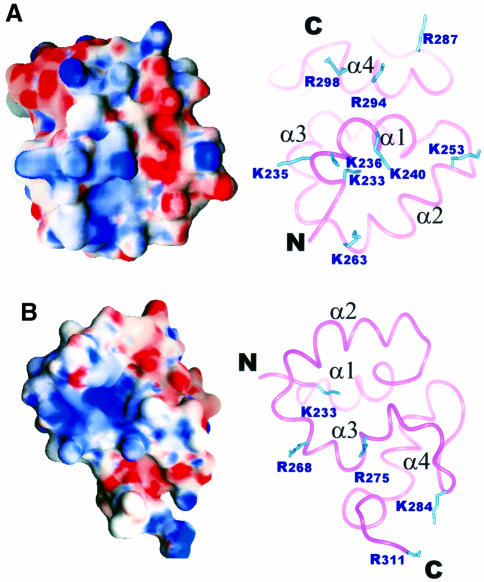

Mu B223–312 is able to bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA (Z.G.Wu and G.Chaconas, data not shown). It is well known that protein–DNA interactions frequently involve large positively charged surfaces from the protein that engage in favourable electrostatic interactions with the negative phosphate backbone (Weber and Steitz, 1984; Warwicker et al., 1985). Such a mechanism would seem plausible given the basicity of Mu B223–312 (pI ∼9.5). In order to identify potential DNA binding surfaces, the Poisson–Boltzmann charge distribution for Mu B223–312 was calculated and mapped to the Connolly surface of the average structure for the protein (Figure 6). As expected the calculation showed that the majority of the surface comprised polar residues with a much smaller hydrophobic content apparent. Close analysis of the surface indicated two extensive positively charged regions. The first positive patch (Figure 6A) is produced from the side chains of four lysine residues (K233, K235, K236 and K240), located near the N-terminus of helix α1, and two arginine residues (R294 and R298) from the C-terminal portion of helix α4. An additional lysine residue (K263) from the C-terminal end of helix α2 completes the patch. The second positive patch is found if the molecule is rotated ∼120° with respect to the first patch (Figure 6B). This region is less extensive than the first patch comprising residues K233, R268 and R275.

Fig. 6. Poisson–Boltzmann charge distribution for Mu B223–312 calculated using GRASP (Nicholls, 1992). (A) The charge distribution was mapped to the Connolly surface of Mu B223–312 with positively charged basic (blue) and negatively charged acidic (red) areas indicated. (B) Same as (A) but rotated ∼120° in a clockwise direction around the x-axis. On the right side of each surface diagram is a ribbon representation showing the side chains of basic residues found at the surface of the protein.

Discussion

The three-dimensional structure of Mu B223–312 represents the first high-resolution structural data for Mu B since its purification 15 years ago (Chaconas et al., 1985b). Until now previous structural attempts were hampered by the extremely low solubility of the protein and its tendency to aggregate. One of the key features of the current work is the use of high ionic strength conditions in order to solubilize the Mu B223–312 protein and obtain the NMR data necessary to determine its three-dimensional structure. The conditions used for Mu B223–312 (1.5 M NaCl) are similar to those used (2.0 M NaCl) for the 43-amino acid DNA binding domain of the γδ resolvase (Liu et al., 1994) where conventional two-dimensional NMR techniques were used for its structure determination. However, Mu B223–312 is more than twice the molecular weight of the resolvase peptide and standard two-dimensional NMR techniques were not sufficient for assignment and structure determination. As a result several three-dimensional NMR experiments (15N TOCSY-HSQC, 15N NOESY-HSQC, 15N HNHA and 13C NOESY-HSQC) in high salt were required to assign the resonances and determine the structure. This approach was complicated somewhat as other useful heteronuclear experiments (13C TOCSY-HSQC and triple resonance experiments) were not practical in 1.5 M NaCl. Nevertheless given the past problems in achieving structural information for the Mu B protein, the Mu B223–312 structure in 1.5 M NaCl represents a major milestone.

The three-dimensional solution structure of Mu B223–312 comprises four α-helices, in agreement with initial circular dichroism studies showing that the protein is mostly α-helical (Chaconas et al., 1989). Nevertheless, the structure of Mu B223–312 has some unique features. For example, a peculiar bend occurs near the middle of helix α3. Initially this observation raised the possibility that high salt conditions may have caused a perturbation in the three-dimensional structure. However, similar helical bends have been observed in several other proteins, notably the N-terminal helix from the phage λ protein N (Legault et al., 1998) and the C-terminal helix from a fragment of the chaperone protein DnaK (Wang et al., 1998). In both cases these helices are ascribed to specialized functions of the proteins. In protein N the bent helix is required to position several arginine side chains near their RNA target. In DnaK, a protein binding region is occluded by the helix. While Mu B223–312 has been shown to bind non-specifically to DNA and has large positively charged surfaces exposed (Figure 6) helix III is notably void of basic side chains, indicating that this region is not important for interactions with DNA.

Correlation of structure and Mu B function

A systematic mutational analysis of the C-terminal domain of Mu B has not been reported. However, it is known that in vivo, a Mu B mutant lacking residues 295–312 is unable to promote replicative transposition but can still facilitate integrative transposition (Chaconas et al., 1985a). Removal of 66 amino acids results in a protein unable to promote transposition of either type. More recently, it has been shown that Mu B lacking residues 295–312 has no ATPase activity in vitro and cannot promote the formation of strand transfer complexes in the presence of ATP (E.C.Greene and K.Mizuuchi, personal communication). Since the ATPase activity resides in the N-terminal domain (Chaconas, 1987; Teplow et al., 1988; Yamauchi and Baker, 1998), these results suggest that ATPase activity in Mu B can be modulated through inter-domainal interactions of the N- and C-terminal portions of the protein. One possibility is that this interaction may lie within the last 18 amino acids of Mu B. This region contains the last turn of helix α4 (residues 295–298) as well as the C-terminal region, which shows much less structural definition. It is not clear how the structure of this region of Mu B might interact with the N-terminal domain to modulate ATPase activity. A second scenario is that the deletion destabilizes the domain. Consistent with this hypothesis, is the fact that A296 and F297 of helix α4 make important contributions to the protein core (see Figure 2B and C). By affecting the stability of the domain, the deletion may be indirectly influencing the structure of another region in the C-terminus that normally interacts with the N-terminal ATPase domain.

The structural homology between Mu B223–312 and the N-terminal domain of DnaB suggests that the two domains share some common functional features(s), especially since deletion of either domain has severe effects on the activity of each intact enzyme. Deletion of the N-terminus of DnaB affects three functions: multimerization, association with other replication proteins and helicase activity (Nakayama et al., 1984; Biswas et al., 1994). We compare and contrast DnaB and Mu B with respect to each of these activities in the search for possible links between the structure and function of the two proteins.

Mu B223–312 has a propensity to dimerize under some conditions (our unpublished results) indicating that the C-terminal domain of Mu B may have a role in protein oligomerization. In DnaB protein dimerization is controlled through interactions between helices α4 and α6 in the C-terminal domain (Fass et al., 1999; Weigelt et al., 1999). Both these helices lie outside the structurally similar region for Mu B comprising helices α1–α3. Thus it appears that oligomerization of Mu B does not occur through a common motif.

DnaB associates with different replication proteins, e.g. DnaC (Wickner and Hurwitz, 1975), DnaA (Marszalek and Kaguni, 1994) and DnaG (Lu et al., 1996). The N-terminus of DnaB is required for interaction with DnaG (Lu et al., 1996) but uses a different part of the domain than the homologous region. Early studies on Mu B suggested that the C-terminal domain might interact with replication proteins since removal of the last 13 amino acids resulted in a specific block to replicative transposition, but not to integration of infecting DNA (Chaconas et al., 1985a). More recently, however, in vitro replication studies have shown that Mu B must be removed before a replication complex can be assembled on the strand transferred product (Kruklitis and Nakai, 1994; Jones and Nakai, 1997, 1999). Unless there are major differences in the in vivo versus the in vitro replication pathways, it seems unlikely that Mu B plays a direct role in the association with replication proteins.

Models of helicase function are predicated upon the cycling between different states, which are dependent upon the presence and/or identity of the bound nucleotide cofactor (Lohman and Bjornson, 1996). Dimerization at the N-terminus of DnaB results in the change from a hexamer with 6-fold symmetry to a hexamer with 3-fold symmetry (San Martin et al., 1995). Presumably, oscillation between these two states, coupled to ATP hydrolysis, allows DnaB to unwind DNA. In DnaB the ATPase activity is in the C-terminal domain (Nakayama et al., 1984), which is not involved in dimerization. A similar situation appears to exist for Mu B. Dimerization of Mu B, presumably through the C-terminal domain, is stabilized by binding of ATP at the N-terminal domain (Adzuma and Mizuuchi, 1991). Kinetic data suggest that the converse is also true—dimerization increases the affinity of Mu B for ATP (Adzuma and Mizuuchi, 1991). For both proteins, the homologous region could thus be involved in coupling dimerization to the ATPase activity that resides in the other domain. In support of this idea is the recent finding that loss of the C-terminal 18 amino acids from Mu B results in inactivation of the distantly located ATPase activity (E.C.Greene and K.Mizuuchi, personal communication). Mechanistically, this last scenario could involve a change in the orientation and packing of the three helices upon dimerization to transduce a signal to the other domain. This is very plausible given the large conformational changes in the N-terminus of DnaB that are known to occur upon dimerization.

To date we have been unable to observe a helicase activity for Mu B. It may be tempting to speculate that Mu B may have a helicase activity that could be useful in melting DNA in the process of strand transfer. However, this does not appear likely given the fact that strand transfer does not require the presence of Mu B. Moreover, even when Mu B and target DNA are present, ATP hydrolysis is not required for strand transfer to proceed.

Concluding remarks

We have solved the structure of Mu B223–312 in high salt and have demonstrated that determining the structure of a protein of moderate size (20 kDa) is feasible under these conditions. This approach may prove useful for NMR studies of other proteins that are sparingly soluble in low salt buffers. The solution structure of Mu B223–312 identifies regions of potential DNA binding and a novel structural motif shared with DnaB. This shared structural motif may be involved in the inter-domainal regulation of the ATPase activity in both proteins. Our results suggest new targets for rational mutagenesis experiments for both proteins. We anticipate that such experiments and additional structural data will help us begin to understand the structure–function of Mu B and its role in transposition.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of Mu B223–312

A fragment encoding GST fused to residues S223–N312 of Mu B (Swiss Protein Data Bank accession No. P03763) was cloned into the pET14b vector (Novagen) for expression in a T7 system. Cells from the wild-type line GC1068 were lysogenized with the DE3 prophage (Novagen kit) and then transfected with the expression construct. Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.1–1.2 and induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM) for 2 h in minimal M9 media supplemented with 13C glucose (1 g/l) and [15N]NHCl4 (0.5 g/l). For each litre of media, cells were harvested by spinning at 8500 g for 7.5 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 20 ml of 25 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA pH 7.5. Cells were lysed for 30 min at 4°C by addition of lysozyme (0.3 mg/ml). This was followed by addition of 1% Triton and antifoam (Sigma) and 10 × 30 s bursts using a Fisher model 300 sonifier at maximum power. Inclusion bodies were washed three times by resuspension by sonication into 25 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton solution (40 ml) at pH 7.5. The inclusion bodies were homogenized in 6 M GuHCl–25 mM Tris (40 ml) at pH 7.5. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 11500 g for 10 min. An equal volume of cold isopropanol was added to the supernatant to precipitate nucleic acids, which were removed by centrifugation at 11 500 g for 10 min. Methanol (4 equiv. by vol) was added to the supernatant, which was allowed to precipitate overnight at –20°C. Precipitated protein was pelleted (11 500 g for 15 min). The pellets were rinsed gently with 25 mM Tris (40 ml) pH 7.5 and re-pelleted (11 500 g for 5 min). Pellets were resuspended in 8 M urea, 25 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (10–15 ml) at pH 7.5. The resuspended protein solution was added dropwise to a stirred beaker containing 25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (9 vols) at pH 7.5 and 25°C. Thrombin (50 µg) was added to the mixture to release the Mu B peptide (G–S223–N312) from the GST moiety and the digestion allowed to proceed for 90 min at 25°C. An equal volume of acetone was added and the protein allowed to precipitate for 2 h at 25°C or overnight at 4°C. The precipitate was pelleted (8500 g for 10 min) and the pellets rinsed with 25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA (50 ml) at pH 8.0 and spun again (8500 g 10 min). Pellets were resuspended in 7 M urea, 25 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (10–15 ml) at pH 8.0 and added to a slurry of 5 ml of CM–Sepharose in 7 M urea, 25 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0. Binding of the protein to the matrix occurred for 1 h with agitation at 4°C. The slurry was pelleted, and resuspended in 7 M urea, 25 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (15 ml) at pH 8.0, which was made into a column. The column was washed with 7 M urea, 25 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (50 ml) at pH 8.0. Protein was then eluted with a 30 ml gradient from 0 to 400 mM NaCl in 25 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 7 M urea at pH 7.5. The protein eluted at 200–300 mM NaCl and the peak fractions were confirmed by PAGE. The pooled fractions were passed through a 0.22 µm filter and loaded directly onto a 25 ml C4 RP column. Before loading the sample, 1 ml of 7 M urea was loaded onto the column and the loop flushed with 7 M urea. After loading the protein solution the loop was left in place and the column washed with 4 column volumes of 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/H2O at 5 ml/min. Elution was carried out with a 1%/min gradient of 0.05% TFA/CH3CN for 25 min followed by a 0.1%/min gradient of 0.05% TFA/CH3CN for 150 min. The peak fractions were identified and the amount of protein estimated by A280 (ε1% 1.42) and lyophilized. The lyophilized protein was resuspended to a concentration of <0.3 mg/ml in 6 M GuHCl, 20 mM Na2HPO4 and 1.5 M NaCl at pH 6.8. The protein was refolded by multiple dialysis versus 20 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 M NaCl at pH 6.8 and concentrated with Amicon concentrators to a final concentration of 7.5–8.0 mg/ml. Yield was ∼3–4 mg/l culture in minimal media.

Collection of NMR data

Spectra were collected with a Varian Unity 500 MHz spectrometer using a triple resonance z-gradient probe. Assignments of the 1H, 15N and 13C resonances are described elsewhere. NOE information used in the structure determination was obtained from a 150 ms 15N NOESY-HSQC (Zhang et al., 1994) using 512 × 128 × 32 complex points for acquisition times of 0.073, 0.018 and 0.027 s in F3, F1 and F2, respectively. A 100 ms 13C NOESY-HSQC (Pascal et al., 1994) was collected using 512 × 128 × 28 complex points for acquisition times of 0.102, 0.026 and 0.009 s in F3, F1 and F2, respectively. A two-dimensional 1H NOESY (512 × 256 complex points for 0.064 and 0.032 s in F2 and F1, respectively) was also collected using a 150 ms mixing time (Macura and Ernst, 1980). Estimates of 3JHN,Hα coupling constants were obtained using a 15N-HNHA experiment (Kuboniwa et al., 1994) for 512 × 64 × 16 complex points and 0.073, 0.01 and 0.01 s acquisition times in F3, F1 and F2. Samples used were 0.75 mM Mu B223–312 in 20 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 M NaCl at pH 6.8. The 15N NOESY-HSQC and 15N-HNHA experiments were conducted with a uniformly 15N-labeled sample in 90% H2O/D2O. The 13C NOESY-HSQC used a uniformly 15N,13C-labeled sample in 100% D2O and the 1H NOESY used an unlabelled sample in 100% D2O. All spectra were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995) and peak-picked using the STAPP/PIPP suite of programs (Garrett et al., 1991).

Structural calculations

Distance restraints were generated from three-dimensional experiments for unambiguous sequential and mid-range NOEs using a program written by Stéphane Gagné (University of Alberta, Canada). Briefly, this approach calculates a distance restraint from the relative intensity of a given NOE and the maximum and minimum NOE intensities for the intramolecular HN–HA distance, which has maximum and minimum distance limits. For long-range NOEs observed in three-dimensional experiments, distance restraints of 1.8–5.0 Å were used. Distance restraints from the 1H NOESY experiment had better signal-to-noise and thus distance restraints of 1.8–6 Å were used for all NOEs identified in this experiment. φ angle dihedral restraints were estimated from 3JHN,Hα coupling constants and use of the Karplus equation. χ-1 angular restraints were obtained by examination of the relative intensity of HN-HB HA-HB NOEs.

Completely unambiguous NOE and dihedral restraints were used to arrive at an initial fold by simulated annealing using the refine.inp script in XPLOR 3.1 (Brunger, 1992). Further ambiguous NOE restraints were identified iteratively from the resulting structures using PERL scripts implementing the NOAH methodology (Mumenthaler and Braun, 1995). Restraints to the simulated annealing runs were added in the following order: intraresidue, sequential, intermediate within secondary elements, intermediate between secondary elements, long range between folded parts of the protein, others from unfolded parts of the protein. Final accepted structures were those with no NOE violations >0.3 Å, no φ angle violations >30°C, no χ angle violations >20° and no backbone angles of the folded part of the protein (residues 230–307) in the disallowed regions of the φ–ψ map.

Procheck-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1993) was used to check backbone angles and to classify the secondary elements. TALOS (a PERL implementation) was used to check secondary structure against that predicted by chemical shifts (Cornilescu et al., 1999). The coordinates for the 20 lowest energy structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 1F6V.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eric Greene and Kiyoshi Mizuuchi (NIH) for communication of unpublished results. We are also grateful to Zheng Guo Wu for making the original GST–MuB fusion construct. We would like to thank Lewis Kay (University of Toronto, Canada) for pulse sequences and advice and Frank Delaglio and Dan Garrett (NIH) for their programs NMRPipe and PIPP. This work was supported by research grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada (G.C. and G.S.S). G.C. gratefully acknowledges the support of an MRC Distinguished Scientist Award from the Medical Research Council of Canada and a Fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

References

- Adzuma K. and Mizuuchi,K. (1991) Steady-state kinetic analysis of ATP hydrolysis by the B protein of bacteriophage mu. Involvement of protein oligomerization in the ATPase cycle. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 6159–6167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T.A., Mizuuchi,M. and Mizuuchi,K. (1991) MuB protein allosterically activates strand transfer by the transposase of phage Mu. Cell, 65, 1003–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S.B., Chen,P.H. and Biswas,E.E. (1994) Structure and function of Escherichia coli DnaB protein: role of the N-terminal domain in helicase activity. Biochemistry, 33, 11307–11314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. (1992) X-PLOR version 3.1: A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G. (1987) Phage Mu. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G. (1999) Studies on a ‘jumping gene machine’: higher-order nucleoprotein complexes in Mu DNA transposition. Biochem. Cell Biol., 77, 487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G., Giddens,E.B., Miller,J.L. and Gloor,G. (1985a) A truncated form of the bacteriophage Mu B protein promotes conservative integration, but not replicative transposition, of Mu DNA. Cell, 41, 857–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G., Gloor,G. and Miller,J.L. (1985b) Amplification and purification of the bacteriophage Mu encoded B transposition protein. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 2662–2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G., McCubbin,W.D. and Kay,C.M. (1989) Secondary structural features of the bacteriophage Mu-encoded A and B transposition proteins. Biochem. J., 263, 19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaconas G., Lavoie,B.D. and Watson,M.A. (1996) DNA transposition—jumping gene machine, some assembly required. Curr. Biol., 6, 817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb R.T., Omichinski,J.G., Savilahti,H., Mizuuchi,K., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1994) A novel class of winged helix–turn–helix protein: the DNA-binding domain of Mu transposase. Structure, 2, 1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb R.T., Mizuuchi,M., Huth,J.R., Omichinski,J.G., Savilahti,H., Mizuuchi,K., Clore,G.M. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1996) The wing of the enhancer-binding domain of Mu phage transposase is flexible and is essential for efficient transposition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 1146–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb R.T., Schumacher,S., Mizuuchi,K., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1997) Solution structure of the Iγ subdomain of the Mu end DNA-binding domain of phage Mu transposase. J. Mol. Biol., 273, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G., Delaglio,F. and Bax,A. (1999) Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and homology. J. Biomol. NMR, 13, 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie R. and Mizuuchi,K. (1985) Mechanism of transposition of bacteriophage Mu: structure of a transposition intermediate. Cell, 41, 867–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie R. and Mizuuchi,K. (1987) Transposition of Mu DNA: joining of Mu to target DNA can be uncoupled from cleavage at the ends of Mu. Cell, 51, 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek,S., Vuister,G.W., Zhu,G., Pfeifer,J. and Bax,A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR, 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fass D., Bogden,C.E. and Berger,J.M. (1999) Crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the DnaB hexameric helicase. Struct. Fold Des., 7, 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett D.S., Powers,R., Gronenborn,A.M. and Clore,G.M. (1991) A common sense approach to peak picking in two-, three- and four-dimensional spectra using automatic computer analysis of contour diagrams. J. Magn. Reson., 95, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N.L., Presnell,S.R. and Cohen,F.E. (1994) Four helix bundle diversity in globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol., 236, 1356–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander,C. (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.M. and Nakai,H. (1997) The φX174-type primosome promotes replisome assembly at the site of recombination in bacteriophage Mu transposition. EMBO J., 16, 6886–6895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.M. and Nakai,H. (1999) Duplex opening by primosome protein PriA for replisome assembly on a recombination intermediate. J. Mol. Biol., 289, 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruklitis R. and Nakai,H. (1994) Participation of the bacteriophage Mu A protein and host factors in the initiation of Mu DNA synthesis in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 16469–16477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa H., Grzesiek,S., Delaglio,F. and Bax,A. (1994) Measurement of HN-HaJ couplings in calcium-free calmodulin using new 2D and 3D water-flip-back methods. J. Biomol. NMR, 4, 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur,M.W., Moss,D.S. and Thornton,J.M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie B.D. and Chaconas,G. (1995) Transposition of phage Mu DNA. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 204, 83–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie B.D., Shaw,G.S., Millner,A. and Chaconas,G. (1996) Anatomy of a flexer-DNA complex inside a higher-order transposition intermediate. Cell, 85, 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legault P., Li,J., Mogridge,J., Kay,L.E. and Greenblatt,J. (1998) NMR structure of the bacteriophage λ N peptide/boxB RNA complex: recognition of a GRNA fold by an arginine-rich motif. Cell, 93, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.C. and Harshey,R.M. (1991) Two mutations of phage mu transposase that affect strand transfer or interactions with B protein lie in distinct polypeptide domains. J. Mol. Biol., 219, 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.C., Teplow,D.B. and Harshey,R.M. (1989) Interaction of distinct domains in Mu transposase with Mu DNA ends and an internal transpositional enhancer. Nature, 338, 656–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., DeRose,E.F. and Mullen,G.P. (1994) Determination of the structure of the DNA binding domain of γδ resolvase in solution. Protein Sci., 3, 1286–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman T.M. and Bjornson,K.P. (1996) Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 169–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.B., Ratnakar,P.V., Mohanty,B.K. and Bastia,D. (1996) Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 12902–12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macura S. and Ernst,R.R. (1980) Elucidation of cross relaxation in liquids by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Mol. Phys., 41, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek J. and Kaguni,J.M. (1994) DnaA protein directs the binding of DnaB protein in initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 4883–4890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell A., Craigie,R. and Mizuuchi,K. (1987) B protein of bacteriophage mu is an ATPase that preferentially stimulates intermolecular DNA strand transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 699–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.L., Anderson,S.K., Fujita,D.J., Chaconas,G., Baldwin,D.L. and Harshey,R.M. (1984) The nucleotide sequence of the B gene of bacteriophage Mu. Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 8627–8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner A. and Chaconas,G. (1998) Disruption of target DNA binding in Mu DNA transposition by alteration of position 99 in the Mu B protein. J. Mol. Biol., 275, 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi K. (1997) Polynucleotidyl transfer reactions in site-specific DNA recombination. Genes Cells, 2, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuuchi M. and Mizuuchi,K. (1989) Efficient Mu transposition requires interaction of transposase with a DNA sequence at the Mu operator: implications for regulation. Cell, 58, 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumenthaler C. and Braun,W. (1995) Automated assignment of simulated and experimental NOESY spectra of proteins by feedback filtering and self-correcting distance geometry. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 465–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigamwalla D.Z. and Chaconas,G. (1997) A new set of Mu DNA transposition intermediates: alternate pathways of target capture preceding strand transfer. EMBO J., 16, 5227–5234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigamwalla D.Z., Coros,C.J., Wu,Z. and Chaconas,G. (1998) Mutations in domain IIIα of the Mu transposase: evidence for an active site component which interacts with the Mu–host junction. J. Mol. Biol., 282, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama C., Teplow,D.B. and Harshey,R.M. (1987) Structural domains in phage Mu transposase: identification of the site-specific DNA-binding domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 1809–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama N., Arai,N., Kaziro,Y. and Arai,K. (1984) Structural and functional studies of the dnaB protein using limited proteolysis. Characterization of domains for DNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis and for protein association in the primosome. J. Biol. Chem., 259, 88–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A. (1992) GRASP: Graphical Representation and Analysis of Surface Properties. Columbia University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Pan B., Deng,Z., Liu,D., Ghosh,S. and Mullen,G.P. (1997) Secondary and tertiary structural changes in γδ resolvase: comparison of the wild-type enzyme, the I110R mutant and the C-terminal DNA binding domain in solution. Protein Sci., 6, 1237–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal S.M., Muhandiram,D.R., Yamazaki,T., Forman-Kay,J.D. and Kay,L.E. (1994) Simultaneous acquisition of 15N and 13C-edited NOE spectra of proteins dissolved in H2O. J. Magn. Reson., B103, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rice P.A. (1997) Making DNA do a U-turn: IHF and related proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 7, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P. and Mizuuchi,K. (1995) Structure of the bacteriophage Mu transposase core: a common structural motif for DNA transposition and retroviral integration. Cell, 82, 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P., Craigie,R. and Davies,D.R. (1996a) Retroviral integrases and their cousins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 6, 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P.A., Yang,S., Mizuuchi,K. and Nash,H.A. (1996b) Crystal structure of an IHF–DNA complex: a protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell, 87, 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Martin M.C., Stamford,N.P., Dammerova,N., Dixon,N.E. and Carazo,J.M. (1995) A structural model for the Escherichia coli DnaB helicase based on electron microscopy data. J. Struct. Biol., 114, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher S., Clubb,R.T., Cai,M., Mizuuchi,K., Clore,G.M. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1997) Solution structure of the Mu end DNA-binding Iβ subdomain of phage Mu transposase: modular DNA recognition by two tethered domains. EMBO J., 16, 7532–7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M.G. and Chaconas,G. (1989) A protein factor which reduces the negative supercoiling requirement in the Mu DNA strand transfer reaction is Escherichia coli integration host factor. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 3028–3034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M.G. and Chaconas,G. (1991) Stimulation of the Mu DNA strand cleavage and intramolecular strand transfer reactions by the Mu B protein is independent of stable binding of the Mu B protein to DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 17306–17313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M.G., Buch,S.J. and Chaconas,G. (1987) Transpososomes: stable protein–DNA complexes involved in the in vitro transposition of bacteriophage Mu DNA. Cell, 49, 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette M.G., Harkness,T. and Chaconas,G. (1991) Stimulation of the Mu A protein-mediated strand cleavage reaction by the Mu B protein and the requirement of DNA nicking for stable type 1 transpososome formation. In vitro transposition characteristics of mini-Mu plasmids carrying terminal base pair mutations. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 3118–3124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplow D.B., Nakayama,C., Leung,P.C. and Harshey,R.M. (1988) Structure–function relationships in the transposition protein B of bacteriophage Mu. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 10851–10857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vis H., Mariani,M., Vorgias,C.E., Wilson,K.S., Kaptein,R. and Boelens,R. (1995) Solution structure of the HU protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 692–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Kurochkin,A.V., Pang,Y., Hu,W., Flynn,G.C. and Zuiderweg,E.R.P. (1998) NMR solution structure of the 21-kDa chaperone protein DnaK substrate binding domain: a preview of chaperone–protein interaction. Biochemistry, 37, 7929–7940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwicker J., Ollis,D., Richards,F.M. and Steitz,T.A. (1985) Electrostatic field of the large fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. J. Mol. Biol., 186, 645–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I.T. and Steitz,T.A. (1984) A model for the non-specific binding of catabolite gene activator protein to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 8475–8487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt J., Brown,S.E., Miles,C.S., Dixon,N.E. and Otting,G. (1999) NMR structure of the N-terminal domain of E.coli DnaB helicase: implications for structure rearrangements in the helicase hexamer. Struct. Fold Des., 7, 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner S. and Hurwitz,J. (1975) Interaction of Escherichia coli dnaB and dnaC(D) gene products in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 72, 921–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. and Chaconas,G. (1994) Characterization of a region in phage Mu transposase that is involved in interaction with the Mu B protein. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 28829–28833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. and Chaconas,G. (1995) A novel DNA binding and nuclease activity in domain III of Mu transposase: evidence for a catalytic region involved in donor cleavage. EMBO J., 14, 3835–3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi M. and Baker,T.A. (1998) An ATP–ADP switch in MuB controls progression of the Mu transposition pathway. EMBO J., 17, 5509–5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang O., Kay,L.E., Olivier,J.P. and Forman-Kay,J.D. (1994) Backbone 1H and 15N resonance assignments of the N-terminal SH3 domains of drk in the folded and unfolded states using enhanced-sensitivity pulsed field gradient NMR techniques. J. Biomol. NMR, 4, 845–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]