Abstract

Adenovirus (Ad)-based vaccines are considered for cancer immunotherapy, yet, detailed knowledge on their mechanism of action and optimal delivery route for anti-tumor efficacy is lacking. Here, we compared the anti-tumor efficacy of an Ad-based melanoma vaccine after intradermal, intravenous, intranasal or intraperitoneal delivery in the B16F10 melanoma model. The intradermal route induced superior systemic anti-melanoma immunity which was MyD88 signaling-dependent. Predominant transduction of non-professional antigen-presenting cells at the dermal vaccination sites and draining lymph nodes, suggested a role for cross-presentation, which was confirmed in vitro. We conclude that the dermis provides an optimal route of entry for Ad-based vaccines for high-efficacy systemic anti-tumor immunization and that this immunization likely involves cross-priming events in the draining lymph nodes.

Keywords: adenovirus, administration route, melanoma

1. Introduction

Metastatic melanoma is the most aggressive type of skin cancer for which surgical intervention prior to metastasis remains the only curative therapy option; novel therapeutic strategies are therefore urgently needed1. Identification and molecular characterization of melanoma antigens recognized by the cellular components of the adaptive immune system have paved the way for the development of viral vector based genetic immunization strategies2. Adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) vectors are the most commonly used vectors for gene delivery and vaccination,3 since the virus exhibits relatively low cytotoxicity, high cloning and replication capacity, and an ability to infect both dividing and non-dividing cells4. Pre-clinically evaluated Ad5 based melanoma vaccines include recombinant Ad5 encoding either murine or human tyrosinase-related proteins (TRP) -1 and-25–7. These tyrosinase-related proteins are melanosomal enzymes endogenously expressed in both melanocytes and melanoma cells8, 9. Perricone et al.10 reported that the administration of adenovirus type 2 vectors encoding murine TRP2 to more than two intradermal sites inhibited subsequent subcutaneous B16F10 tumor growth. In contradiction to this study conducted with Ad2 vectors, vaccination of mice with Ad5 encoding autologous full-length TRP2 did not induce effective TRP2 specific cellular immune responses, nor did it result in the eradication of B16F10 melanoma tumors7. However, vaccination of mice via the intraperitoneal (i.p) route with Ad5 encoding xenogenic human TRP2 or the murine immunodominant aa180–188 epitope TRP2 fused to the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) containing immunogenic foreign helper sequences (Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188), was able to overcome peripheral tolerance and induce effective TRP2 specific CD8+ T cells via a CD4+ T cell dependent mechanism2. The thus induced TRP2 specific immune response completely prevented the outgrowth of lung metastases but not subcutaneous growth of B16 melanoma cells2, 11. Whether this was due to a route of immunization-dependent induction of a compartmentalized antigen specific cellular immune response has not yet been further evaluated. The identification of optimal routes of administration of Ad5 based melanoma vaccines to induce systemic immune responses may prove particularly important in order to eradicate metastatic tumors growing in distinct tissues of the body (e.g. skin, lung, brain or visceral tissue). In the present study, we evaluated the effects of administration route on the specific CD8+ T cell priming efficacy of Ad5-GFP-TRP2 and the ability of the primed effector cells to eradicate B16F10 tumors growing in different sites of the body, i.e. subcutaneous (s.c.) vs. lung. The administration routes compared were i.p, intravenous (i.v.), intranasal (i.n.) and intradermal (i.d.) The latter proved most effective, inducing potent systemic TRP2-specific CD8+ T cell immunity and resulting in the complete prevention of B16F10 melanoma outgrowth in the subcutis as well as in the lung.

A critical factor in inducing immune response against self antigens such as TRP2 is efficient delivery of the vaccine to professional antigen presenting cells (APC), i.e. dendritic cells (DC)8. Skin contains both epidermal (Langerhans cells, LC) and dermal DC, while skin-draining LN contain both resident and skin-derived DC populations. In the classical paradigm, skin DC have been recognized as key APC, capable of priming naive T cell responses12. In contrast, LN resident CD8α+ DC, rather than skin DC, have been reported to be key APC for priming CD8+ T cell responses against antigens encoded by vaccinia virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and influenza A viruses13–15. However, the role of skin-derived DC in Ad-induced CD8+ T cell responses has not been reported. This led to us to investigate the possible role of skin DCs in the Ad5-mediated induction of CD8+ T cell responses. In addition, we investigated the involvement of MyD88-dependent signaling events. Ad5-induced innate immune responses are mediated by Toll-like receptors (TLRs)16. The mammalian TLRs are a family of highly conserved, germline-encoded transmembrane receptors that recognize conserved microbial products (Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns, PAMPs). Detection of PAMPs by TLRs recruits distinct sets of adapter molecules that in turn activate specific downstream signalling molecules leading to the induction of an immune response and elimination of invading pathogens17, 18. TLRs can signal through four adaptors identified to date19. Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) is a key adaptor for most TLR-dependent inflammatory signaling pathways as well as for IL-1R1, IL-18R1 and IFNγR1 signaling pathways20. MyD88 interacts with a variety of cellular proteins leading to the activation of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPKinase and the induction of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and type I interferons20, 21. A key role for MyD88 in Ad5 induced pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, activation of DCs and antigen specific adaptive immune responses has previously been reported16, 22–24. Here we present evidence to suggest that Ad5-based i.d. vaccine efficacy is cross-priming and MyD88 dependent, but does not require skin-derived DCs nor DC-based MyD88 signalling.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and cell lines

Five- to ten-week old C57BL/6 wild-type mice (H-2Kb) were purchased from Harlan, The Netherlands, and MyD88−/−KO mice from C57BL/6 (H-2Kb) background were kindly provided by Dr. Akira, Osaka University. Japan. Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages with filter top in the experimental animal facility of the VU University medical center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Animal experiments were carried out following EU and national guidelines and were approved by an institutional scientific and ethical review committee. B16F10 (H-2Kb), a spontaneous murine melanoma cell line was maintained in DMEM (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 I.E./ml sodium penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulphate, 2mM L glutamine, and 0.01 mM 2-mercapoethanol. The mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 (H-2q) was also cultured in DMEM but it was supplemented with 10% heat inactivated normal calf serum instead of fetal calf serum.

2.2. Peptides

The H-2Kb binding peptide SVYDFFVWL (TRP2aa180–188) derived from the murine melanosomal protein Tyrosinase-Related Protein 2 (TRP2), and the H-2Kb binding peptide ICPMYARV (βgalaa497–504) derived from Escherichia coli β-galactosidase were purchased from the peptide synthesis facility of the Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands. Peptides were dissolved at a concentration of 10 µg/ml in PBS containing 10% DMSO and stored at −20°C until use.

2.3. Ad vectors, vaccination, vaccination site excision and tumor inoculation

Replication defective, E1 and E3 region deleted Adenovirus type-5 (Ad5) vectors encoding only enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP)25 or both eGFP and a single H-2Kb binding and TRP-2-derived peptide epitope (TRP2aa180–188) under the control of cytomegalovirus promoter7 were used in this study. The Ad5 vectors were propagated in HEK293 cells, purified by ultracentrifugation on caesium chloride gradients, Ad5 vector titres were determined using standard protocols (Adeno-X™ rapid titration kit, Clontech lab Inc, Mountainview, CA, USA) and stored frozen at −80°C until use.

Mice were vaccinated twice at days -14 and -7 with 1×107 infectious units (i.u.) of Ad5 vectors re-suspended in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using a MicroFine insulin syringe with 29G needle(BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) by interdermal (i.d) (50µl, flank skin), intravenous (i.v) (100 µl, tail vein) or intra-peritoneal (i.p) (100 µl) routes. Pipette with 100µl filter tip (Greiner bio-one, Kremsmünster, Germany) was used for delivery of the vector by intranasal (i.n.) route. In some experiments, vaccination site excision was performed 4h post i.d. vaccination using sterile scissors and the excision wound was closed using surgical staples and glue (3M Nederland BV, Leiden, Netherlands).

Mice were injected with either PBS or Ad5-GFP (1×108 i.u/mice) via i.d. administration in the flank skin to evaluate the in vivo DC transduction efficiency. The skin from the site of injection of PBS or Ad5-GFP and respective injection site draining lymph node LN (axillary) were harvested at 24h post injection and analyzed by immunofluorescent staining.

Mice were implanted either s.c. (s.c. tumor model) or i.v. (through the tail vein, lung metastasis model) with 2×105 syngeneic B16F10 cells resuspended in 50µl or 100 µl PBS, respectively at d 0. S.c. tumor diameters were monitored using a digital slide calliper every 3–4 days until the end of the experiment. The reported tumor volumes were calculated using the formula (0.4)*(ab2), with "a" as the larger diameter and "b" as the smaller diameter26. Mice with i.v. administered tumor cells were sacrificed after 11 days post-inoculation by an overdose of anaesthesia; the lungs were collected, bleached in Fekete’s solution27 and subsequently fixed for 2 days in 10% formaldehyde. After fixation, all lobes were dissected, digitally photographed and the number of surface metastases were counted using Adobe Photoshop software.

2.4. Monoclonal antibodies and MHC tetramers

PE- or FITC-labeled mAbs directed against IA/IE or murine CD11c, CD8β, or CD4 and a FITC-labeled mAb directed against murine IFNγ (all from BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used to determine frequencies of DC or CD8+ and CD4+ T cells recognizing TRP2 peptide and producing IFNγ by flow cytometric analysis after intracellular IFNγ staining.

Antigen-specific T cell analysis was further performed by staining splenocytes with AlloPhycoCyanin (APC)-labeled H2Kb-tetramers loaded with the TRP2 peptide SVYDFFVWL (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Antibody or tetramer staining was performed in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA and 0.02% Sodium-Azide for 30 min at 4°C or 15 min at 37°C, respectively. Cells were counterstained with anti-CD8β (Ly-2; PharMingen) and analysed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). In addition, samples were stained with 0.5 µg/ml Propidium Iodide (ICN Biomedicals, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands) for dead cell exclusion. Within the CD8+ T cell population the percentage of tetramer-positive cells was determined after gating on forward scatter and exclusion of propidioum idodide positive cells using CellQuest Pro analysis software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

2.5. IFNγ intracellular staining

The IFNγ intracellular staining (ICS) assay was carried out as described previously by Elia et al.28 with minor modifications using an intracellular staining kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Briefly, two to three million mouse PBMC or splenocytes were stimulated with either TRP2aa180–188 or βgalaa497–504 at a concentration of 1µg/ml for 4–5 h at 37°C in the presence of 0.5 µl/ml golgiplug (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were washed, stained with CD8-PE and CD4-APC antibodies, fixed, permeabilized and incubated with the FITC conjugated anti-mouse IFNγ mAb (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, using CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

2.6. Tissue fixation and immunofluorescence microscopy

Skin biopsies from the site of vaccination and the vaccination site draining LN (axillary, identified by injection of Evans Blue dye [Sigma, St. Louis, MO]) were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 10% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for 30 min29. Fixed tissues were embedded in Tissue-Tec OCT (Sakura Fineteck, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) above liquid nitrogen. 10µm-Cryosections were cut from frozen tissue blocks and mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. Slides were dried at room temperature (RT) overnight, fixed in cold acetone at 4°C for 10 min and then stored at −20°C until use.

Slides were brought to RT and placed in PBS for 5min to remove OCT; endogenous biotin was blocked (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and slides were stained with biotinylated anti-IA/IE or anti-CD11c mAbs (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Specific binding of the antibody was detected using Cy3-conjugated streptavidine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DAPI (Molecular probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was used to stain nuclei and slides were mounted using mounting medium (Immunoconcepts NA Ltd, Sacramento, CA, USA). Staining was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon instruments BV, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) using appropriate filters.

2.7. In vitro antigen-specific (cross-) presentation

Bone Marrow-Derived DC (BMDC) were generated from BMC WT or MyD88−/−KO mice as described by Samsom et al.30 and were directly transduced with Ad5 vectors encoding TRP2aa180–188. Transgene expressing DC were plated in round bottom 96 well plate (Greiner Bio-one) with splenocytes containing TRP2-primed CD8+ T cells isolated from mice vaccinated with Ad vectors encoding the TRP2 epitope at a ratio of 1:10. After overnight stimulation, percentage of CD8+ T cell producing intracellular IFNγ was determined by flow cytometry as described above.

To determine the cross-presentation capacity of BMDC from WT vs. MyD88−/−KO mice, HLA a mismatched murine embryonic fibroblast cell line (NIH3T3 on a H-2q background) was infected with Ad5 encoding TRP2aa180–188. After 24hr of infection TRP2aa180–188 expressing NIH3T3 cells were harvested, washed extensively and co-incubated with BMDC from WT or MyD88−/−KO mice in a 1:10 ratio for another 24hr. Subsequently, BMDC were harvested and used to stimulate TRP2 specific CD8+ T as described above.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using one way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction using GraphPad Prism software.

3. Results

3.1. Intradermal delivery of the Ad-TRP2 vaccine induces superior CD8+ T cell reactivity

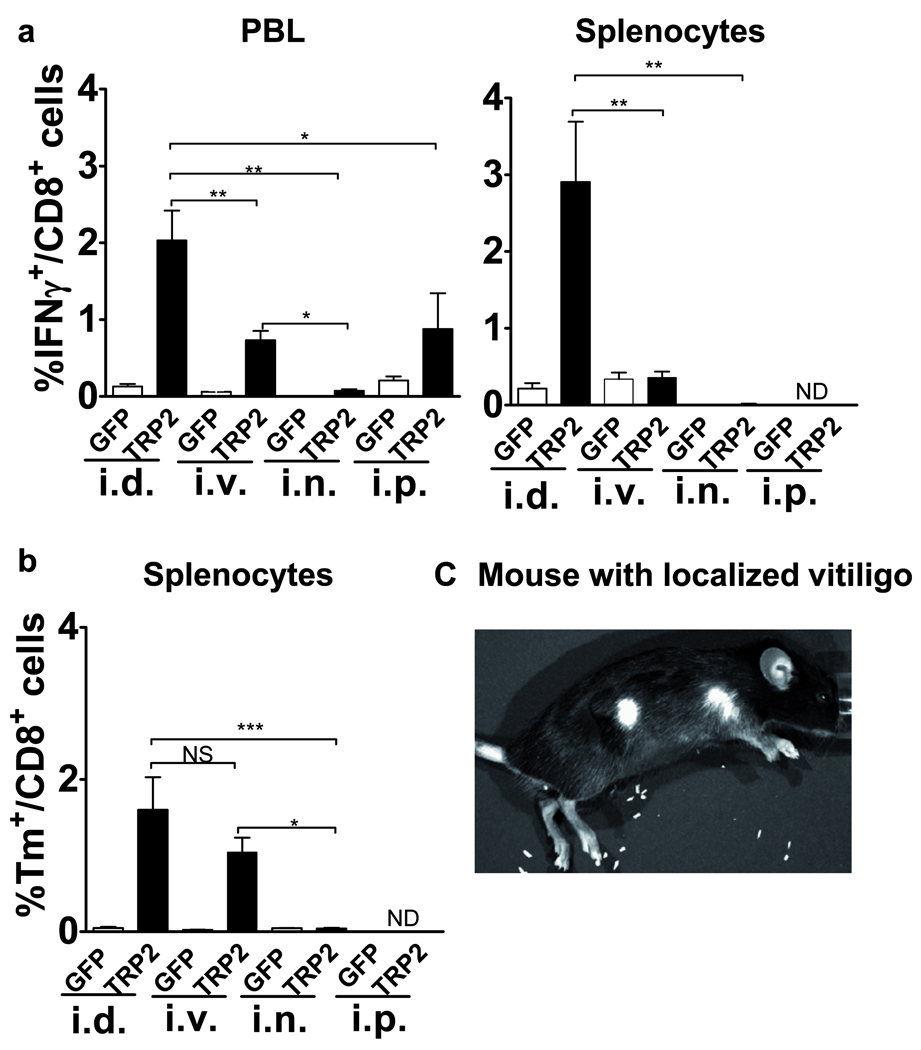

A previous study reported the i.p. route of delivery of an Ad5-based vaccine to induce strongest CD8+ T cell responses against an epitope derived from the exogenous antigen Ovalbumin (OVA) as compared to other administration routes31. Here, we evaluated the optimal delivery route of an Ad5 vaccine to induce an effective systemic CD8+ T cells response against a melanoma-specific self antigen, TRP2. We made a head-to-head comparison of antigen specific CD8+ T cell levels in the PBL 13 days post-vaccination and in the splenocytes 27 days post-vaccination, between mice vaccinated with Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 via i.d., i.v., i.n., and i.p. routes. To measure the TRP2aa180–188 specific immune response, INFγ+ ICS analysis was carried out with PBL and splenocytes re-stimulated in vitro with the H-2Kb binding TRP2aa180–188 peptide. In addition, tetramers (Tm) were used to quantify TRP2aa180–188 specific CD8+ T cell levels in the splenocytes. The i.d. route of vaccination induced the strongest as well as a long lasting (at least up to 27 days post-vaccination) specific CD8+ T cell response as determined by the frequency of IFNγ producing CD8+ T cells and Tm analysis in both PBL and splenocytes (Fig. 1a). Detectable but lower responses were achieved by i.p. and i.v routes of vaccination, whereas no reactivity was detectable upon i.n. vaccination (Fig. 1ab). Of note, i.v. route of vaccination appeared to induce TRP2-specific T cells impaired in cytokine production as specific T-cell frequencies measured in splenoctyes using Tm did not correlate with the specific T cell frequencies determined using IFNγ+ ICS analysis at 27 days post-vaccination (Fig. 1ab). In accordance with the observed higher TRP-2-specific T cell rates, only i.d. vaccination induced localized coat depigmentation at the vaccination site as well as at the site of s.c. tumor inoculation (Fig. 1c), indicating effective breaking of tolerance and an autoimmune mediated destruction of melanocytes.

Figure 1.

The intradermal (i.d.) route of administration of Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 induces superior (i.e. strong and long-lasting) TRP2-specific CD8+ T cell reactivity as compared to intravenous (i.v.), intranasal (i.n.) or intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration. a) INFγ producing CD8+ T cells in both peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) and splenocytes harvested on day 13 and 27 post-vaccination respectively, were detected by flow cytometric analysis after in vitro stimulation with the TRP-2aa180–188 peptide. b) TRP2 specific T cell frequencies were also determined using TRP-2 tetramers (Tm) in splenocytes harvested at day 27 post vaccination. Presented data are means ± SEM (n=3–6). c) Mouse with localized coat depigmentation at the vaccination site as well as at the site of s.c. tumor inoculation. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the variances were compared with Bonferroni test. Differences between the groups were considered significant when P<0.05. * P<0.05, **<0.01 & ***<0.001.

3.2. Only i.d. delivery of Ad5-GFP-TRP2 protects mice from the outgrowth of B16F10 tumors in either the subcutis or the lung

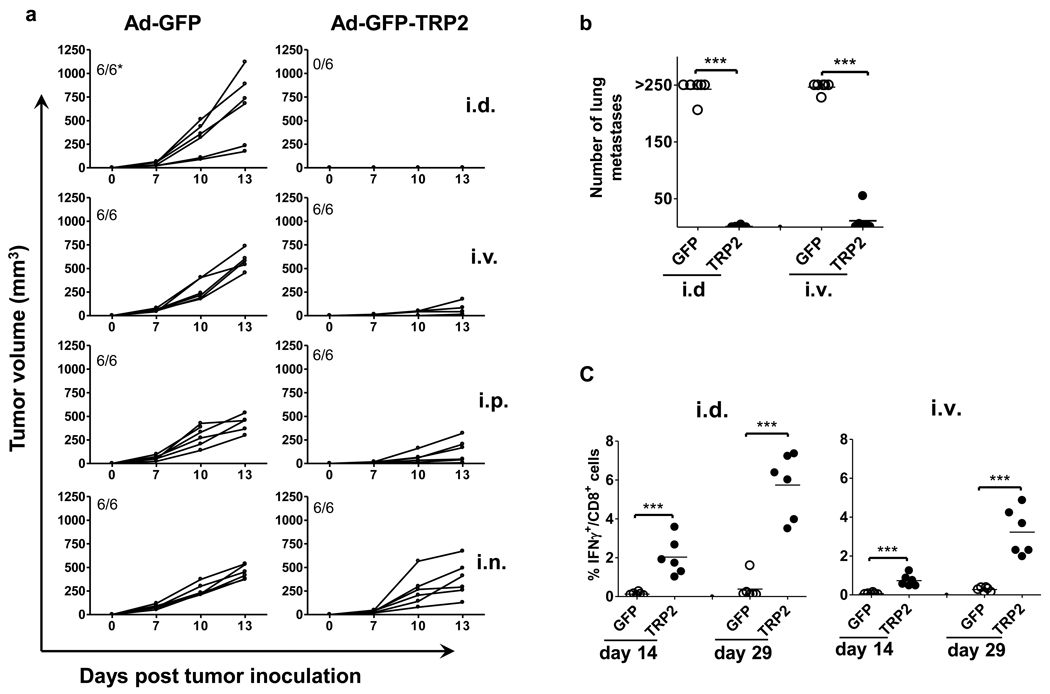

Previous studies have reported on the effects of different routes of application of antigen-pulsed DC vaccines and of Ad vectors encoding exogenous model antigens on the anti-tumor efficacy32–35. We investigated whether route of application also affects the anti-tumor efficacy of the Ad5-GFP-TRP2 vaccine using the B16F10 subcutaneous melanoma model. Only i.d. route of application completely and i.v. route of application partially protected mice from subcutaneous growth of B16F10 melanoma, whereas other routes of application did not show any significant anti-tumor efficacy (Fig. 2a). We also evaluated the anti-tumor efficacy of both i.d and i.v. vaccination routes using the B16F10 lung metastasis model. The data shown in Fig. 2b reveal that both i.d and i.v. vaccination protected mice from the outgrowth of lung metastases to a similar degree. Of note, this protection was accompanied by the systemic induction of strong and long-lasting TRP-2-specific CD8+ T cell responses (detectable in the blood upto 29 days post-vaccination, Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

The intradermal (i.d.) route of administration of Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 (10×106 i.u./mice) protects mice from both subcutaneous (s.c.) growth as well as lung metastasis of B16F10 melanoma cells, in contrast to intravenous (i.v.), intranasal (i.n.) or intraperitoneal (i.p.) routes of vaccination. a) Kinetics of s.c. growth of B16F10 melanoma cells in mice prophylactically vaccinated with control (Ad5-GFP) or Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 virus at d -14 and boosted at d -7 via i.d., i.v., i.n., and i.p. routes. Each plotted line represents tumor growth kinetics in an individual mouse (n=6). *Indicated is the number of tumor bearing mice/total number of mice. b) Number of macroscopically visible metastases on the surface of the lungs of mice vaccinated with Ad5-GFP or Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188. Each plotted value represents an individual mouse (n=5). c) INFγ producing CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood leukocytes harvested on day 14 and 29 post-vaccination from the animals tested for the outgrowth of lung metastases, were detected by flow cytometric analysis after in vitro stimulation with the TRP-2aa180–188 peptide. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the variances were compared with Bonferroni test. Differences between the groups were considered significant when P<0.05. ***P<0.001.

3.3. TRP2 specific CD8+ T cell responses induced by Ad5-GFP-TRP2 are most likely due to the cross-presentation of antigen by DC in draining LN

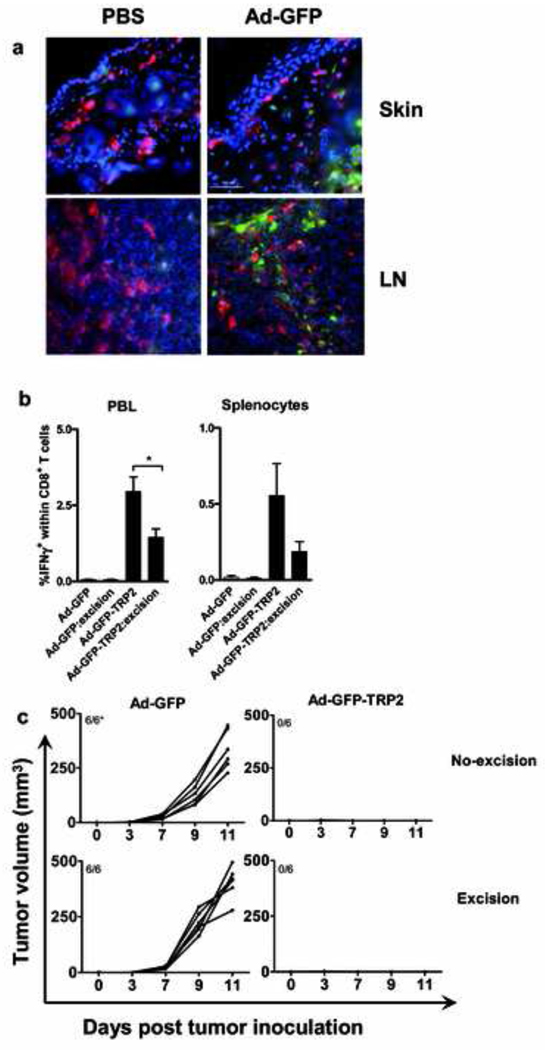

The potent TRP2 specific CD8+ T cell response induced by i.d. administration of Ad5-GFP-TRP2 prompted us to determine whether Ad5 efficiently delivered transgenes to DC in the flank skin and the auxiliary draining LN. We assessed GFP expression in the DC, 2 days after i.d. injection of Ad5-GFP. Skin DC identified by MHC-II expression and DC in draining LN, identified by CD11c expression, were not transduced by Ad5-GFP (Fig. 3). GFP expression was observed in MHC-II and CD11c negative skin- and LN-resident cells, which, based on localization (deep dermis and LN sinuses, Fig. 3a) and morphology are most likely fibroblasts, suggesting the induced CD8+ T cell responses to result from cross-presentation by DC. This was further corroborated by ex vivo infection of skin and LN suspensions; 24h after infection flow cytometric analysis did not reveal any GFP expression in MHC-II+CD11c+ DC (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Intradermal administration (i.d.) of Ad5-GFP predominantly leads to transduction of non-dendritic cells (DC) and skin DC are dispensable for the induction of an effective anti-tumor response by Ad5-GFP-TRP2. a) Mice were injected with either PBS or Ad5-GFP (1×108 i.u/mice) via i.d. administration in the flank skin. The skin from the site of injection of PBS or Ad5-GFP and respective injection site draining lymph node LN (axillary) were harvested and analyzed by immunofluorescent staining. Virus transduced cells were detected by transgene GFP (green) expression and dendritic cells in the skin were detected using anti-IA/IE antibody (red) and the LN DCs with anti-CD11c antibody (red). Cell nuclei were detected using DAPI (blue) (magnification 400×). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with each experimental group consisting of two to three mice. b) Mice were i.d. vaccinated with Ad5-GFP-TRP2 (1×107 i.u/mice) on the flank skin and the vaccination site was surgically excised after 4h. Rates of IFNγ producing CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood leukocytes (7 d post vaccination) and splenocytes (18 d post vaccination) were determined by flow cytometric analysis after in vitro restimulation with the TRP2aa180–188 peptide. Means ± SEM are plotted (n=6). Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the variances were compared with Bonferroni test. Differences between the groups were considered significant when P<0.05. *P<0.05. c) Kinetics of s.c. growth of B16F10 melanoma cells in mice prophylactically vaccinated via i.d. route with control (Ad5-GFP) or Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 and similarly vaccinated mice in which the vaccination site was surgically excised after 4h. Each plotted line represents tumor growth kinetics in an individual mouse (n=6). *Indicated is the number of tumor bearing mice/total number of mice.

To study the importance of skin-derived cells in TRP2 specific immune induction by the Ad5 vector, the dermal vaccination site was surgically excised 4h post vaccination. Data show that such surgical intervention significantly reduced TRP2-specific CD8+ T cell rates (Fig. 3b), but did not affect anti-tumor efficacy (Fig. 3c)

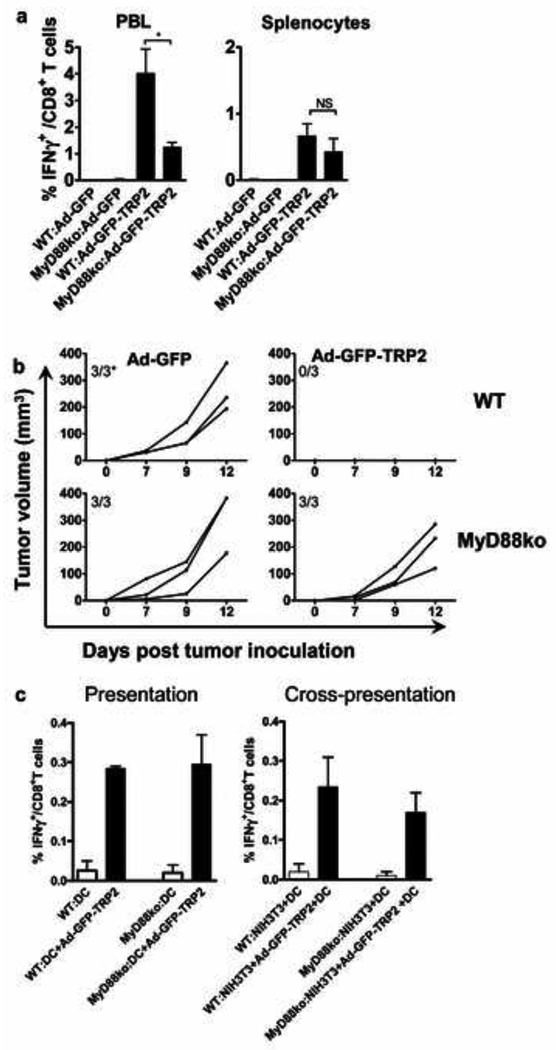

3.4. MyD88 deficiency impairs the induction of effective anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses by i.d. Ad5-GFP-TRP2 delivery but does not affect (cross-) presentation by DC

MyD88−/− KO mice were used to evaluate the role of this critical TLR adapter gene in the induction of TRP2 specific T cell responses by Ad5-GFP-TRP2. The obtained data revealed that TRP2-specific T cell frequencies were significantly lower in PBL of Ad5-GFP-TRP2-vaccinated MyD88−/−KO mice as compared to MyD88+/+wt mice at 13 days post-vaccination but not at 29 days-post vaccination in the splenocytes (Fig 4a). Similarly, MyD88 signaling was required for the complete protection against the outgrowth of s.c. tumors observed upon i.d. vaccination with Ad5-GFP-TRP2 (Fig. 4b). As TLR-mediated activation of professional APC, i.e. DC, is generally regarded as essential for the induction of effective cell-mediated immunity, we investigated the requirement of MyD88-competent DC in Ad5-based CD8+ T cell (cross)-priming. In vitro studies revealed that MyD88−/− DC were able to both present and cross-present the TRP2 transgenic epitope to TRP2-specific T cells and to induce their antigen-specific production of IFNγ with the same efficiency as that of MyD88 competent wt DC (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

TRP2 specific CD8+ T cell responses induced by intradermal administration of Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 depend on the MyD88 adapter protein but not at the dendritic cell (DC) level. a) IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cell rates were determined in peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) and splenocytes harvested from both C57Bl/6 wild type (WT) and MyD88−/− KO mice on day 13 and 27 post-vaccination, respectively. IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometric analysis after in vitro restimulation with the TRP2aa180–188 peptide. Means and SEM were plotted (n=5). Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the variances were compared with Bonferroni test. Differences between the groups were considered significant when P<0.05. b) Kinetics of s.c. growth of B16F10 melanoma cells in WT and MyD88−/−KO mice prophylactically vaccinated with control (Ad5-GFP) or Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 virus through i.d administration. Each line represents the kinetics of tumor growth in an individual mouse (n=3). Data shown are representative of two independent experiments conducted with each experimental group consisting of three mice. *Indicated is the number of tumor bearing mice/total number of mice. c) WT or MyD88−/−KO DC directly transduced by Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188 or co-incubated with Ad5-GFP-TRP2aa180–188-transduced, MHC-mismatched fibroblast (NIH3T3) cells were used to test the antigen presentation or cross-presentation ability of DC. Transduced or co-incubated DC were used to stimulate splenocytes from TRP2aa180–188 immunized WT mice. The percentage of INFγ-producing cells within CD8+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry after intracellular staining. Means and SEM are shown from two independent experiments.

4. Discussion

In the present study we show that the route of administration of an Ad5-based melanoma vaccine determines the magnitude of the induced melanoma specific CD8+ T cell response and the control of localized tumor outgrowth. The significance of the selected route of vaccine administration in the induction of systemic anti-tumor CTL immunity has been thoroughly investigated using DC based cancer vaccines32, 35, 36. Mullins et al.,35 showed that route of administration of a DC based vaccine determined the location of primary T cell activation, distribution of memory T cells and control of localized tumor outgrowth. Recently, the impact of Ad5 vector immunization via different routes on biodistribution of the vector has been studied.31, 37, 38 Also, the impact on the induction of antigen specific CTL responses has been studied using Ad5 encoding non-self model antigens, chicken ovalbumin (OVA) and β-galactosidase.31, 38 The first study revealed the i.p. route of administration to be most effective in inducing OVA specific CD8+ T cell responses, whereas the s.c. route proved to be most potent in the latter study. However, neither study evaluated the anti-tumor efficacy of the induced immune response. Studies on the biodistribution of Ad5 vectors administered via different routes have revealed that through the i.d. route of administration, transgenes are delivered to the vaccination site and reach the local draining LN; through the i.v. route transgenes reach the liver, spleen, LN and other organs, through the i.p. route the draining LN and spleen and through the i.n. route the lungs, brain and draining LN.31, 37 These data suggest that the wider distribution achieved through the i.p. and i.v. routes of administration should facilitate a more widespread Ad5-induced systemic immune response than permitted by the i.d. route. However, we clearly found the i.d. route of vaccination to induce the most potent systemic anti-tumor CD8+ T cell response when compared with other routes of vaccination. This is probably due to the presence of a vast network of Ad5 susceptible fibroblasts in the murine skin and ready access to high numbers of DC in the skin and its draining LN. Here, we did not compare i.d with the s.c. route of administration, however, we believe that a slight modification of the depth of injection could significantly hamper the efficacy of vaccination due to the absence of DC and accessible lymphatic vessels in s.c. layers and consider it therefore vital that the viruses are delivered i.d.10, 39 Even though Ad5 vectors have been reported to be very effective for delivering transgenes to mucosal tissues, due to their natural tropism for mucosal epithelia, we failed to detect any TRP2 transgene-specific T cell responses either in peripheral blood or in spleen upon i.n. A5 delivery.37, 40 Further research is needed to establish whether this is due to differences in tissue homing ability of the specific T cells primed in mucosa-draining LN as previously reported for DC based vaccines.34, 35 Alternatively, the mucosal surface targeted through i.n. Ad5 delivery, may not be sufficiently conducive to the generation of effective cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity, but rather lead to humoral immunity or, in the absence of proper danger signals, even lead to tolerance induction41.

Skin is a sensitive immune organ due to the presence of a dense network of professional APC, i.e. Langerhans Cells (LC) and demal DC, and hence forms an attractive site for vaccination. DC are capable of breaking peripheral tolerance and initiating adaptive immune responses against self antigens. As most tumor antigens are self antigens against which considerable peripheral tolerance is maintained, targeted delivery of tumor antigens to DC has been considered a promising immunotherapeutic approach to overcome peripheral tolerance and to promote anti-tumor immune responses. Although Ad5 vectors are being considered as a tumor vaccine vehicle, they do not efficiently infect DC in vitro.42 Nevertheless, i.d. Ad5-eGFP-TRP2 vaccination induced potent anti-tumor immune response in mice. We therefore decided to investigate whether the employed Ad5 vector delivered their transgene to DC in the skin vaccination site and its draining LN. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that the GFP transgene was not expressed in skin DC. Even though specific characterization of the transgene expressing cells was not undertaken in the present study, we speculate based on previous observations43 and localization and morphological features that a large portion of the transgene-expressing cells were fibroblasts. These findings indicate that the direct transduction of DC is not required for the injected Ad5 vectors to elicit TRP-2-specific T cell responses but that this was likely achieved by cross-presentation of the Ad5-encoded epitope by DC. This is in line with a previously reported Ad5-induced influenza A nucleoprotein-specific CD8+ T cell response in mice which also depended on cross-priming44. Indeed, we found the transgenic TRP2 epitope to be readily cross-presented by DC upon co-incubation with allogeneic (MHC miss-matched) transduced fibroblasts in vitro. Although these findings demonstrate high efficacy of Ad5 vaccines without direct DC infection, this may be strictly inherent to the use of a vector encoding a defined CD8+ T cell epitope fused to foreign (eGFP) CD4+ helper T cell epitopes, rather than a full-length self protein. This could have facilitated the rapid and highly efficient dissemination of the epitope to surrounding bystander cells (including APC) and subsequent high-efficacy cross-presentation. Indeed, i.d. vaccination with an Ad5 vector encoding full-length TRP2 could not induce protective anti-melanoma immunity (our own findings, data not shown). Thus, for efficacious i.d. vaccination with Ad5 vectors encoding full-length tumor antigens, targeted in vivo delivery of the transgene to DC may be warranted. We are currently investigating this issue further.

Skin-derived DCs were thought be the key players in the initiation of CD8+ T cell immunity upon viral infection of the skin.45 A study with a lentiviral vector has indeed demonstrated the direct role of skin DC in the induction of CD8+ T cell responses12, but studies with HSV have shown that skin DC have little direct involvement in CD8+ T cell priming.14, 46 To further elucidate this issue for Ad5-based vaccination, we removed the skin vaccination site 4h after i.d. Ad5 injection. Even though skin DC subset-specific involvement in antigen-specific CD8+ T cell priming was not evaluated in the present study (i.e. LC vs dermal DC subsets), based on the reports that both LC and dermal DC take longer than 12h to reach draining LN,46 we can conclude that most likely DC in skin-draining LN and not skin-derived DC are dominantly involved in (cross)-presentation of Ad5 vector delivered TRP-2 antigen to naïve CD8+ T cells in skin draining LN and the subsequent induction of protective anti-tumor immunity. CD8α+ DC would be the most obvious candidate subset in this regard.13–15 Unlike previous reports on abrogation of Herpes simplex virus or plasmid DNA encoding OVA induced T cell response upon scarification of immunization site,46, 47 excision of Ad5-eGFP-TRP2 immunization site within a few hours post-vaccination i.d., did not completely abrogate the immune response and more importantly, had no effect on protection against subsequent tumor outgrowth. Whether the observed reduction in specific CD8+ T cell responses in the immunization site-excision group was either due to an overall reduction in the antigenic load or due to removal of antigen-exposed skin DC will require further investigation.

The role of TLR signalling in viral vector-induced innate and adaptive immune responses has been studied using MyD88 deficient mice16, 22, 23, 48, 49. There are contradictory reports on the ability of MyD88 deficient mice to mount a pro-inflammatory innate immune response to Ad5 infection22, 48. Interestingly, no defect in maturation of DC from MyD88 deficient mice upon exposure to Ad548 or vaccinia virus49 has been reported. Indeed, a recent report suggests that Ad5-induced activation of murine DC in vitro may be TLR-dependent but MyD88 independent24. We found MyD88 to be critical for Ad5-induced protective anti-tumor immunity in vivo. This is in line with previous findings on the role of MyD88 in Ad5-induced CTL reactivity against the carcinoembryonic antigen23 and vaccinia virus (VACV) induced VACV-specific effector CD8+ T cell response49. Our observation of hampered anti-melanoma immunity in vaccinated MyD88−/−KO mice appeared not to be due to an impaired antigen (cross-)presenting capacity of DC, as MyD88 deficient DC matured normally (data not shown) and were also able to stimulate and induce production of IFNγ in TRP2-specific CTL following Ad-GFP-TRP2 infection or co-culture with infected fibroblasts in vitro. Beside DC, other (non-)immune cells have also been found to express and signal through MyD88, e.g. macrophages50 and CD8+ T cells51. Elimination of local macrophages through i.d. injection of liposome-complexed clodronate prior to i.d. vaccination with Ad5 in our hands did not interfere with vaccination efficacy (data not shown), excluding a possible role for macrophages in the observed induction of protective CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Recent studies have demonstrated that T cell-expressed MyD88 plays an important intrinsic role in lymphocytic choriomeningitis and vaccinia virus induced specific CD8+ T cell survival and accumulation during clonal expansion52–54. It is tempting to speculate that Ad5-induced transgene specific CD8+ T cells may similarly depend on MyD88 mediated signaling processes for clonal expansion and survival. Alternatively, TLR expressed in assessory cells in vivo such as e.g. fibroblasts, may have led to MyD88-mediated signaling and cytokine release upon Ad5 infection, which in turn may have activated neighbouring DC. Further studies are needed to clarify the precise mechanism underlying the observed dependence on MyD88.

In summary, i.d. vaccination with an Ad5-based tumor vaccine was found to be the optimal delivery route for the induction of a systemic antigen specific T cell response, able to prevent establishment of both s.c. and lung tumors. The administered Ad5 did not directly infect and transduce DC but rather infected fibroblast-like cells. The subsequent induction of protective T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity most likely depended on cross-presentation of antigen by DC in draining LN and involved signalling through the MyD88 adaptor protein (but not at the DC level). Present findings suggest that the route of administration and also the anatomical location of the tumors should be taken into consideration when Ad5-based vaccines are designed and evaluated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF-grant VU2005-3284), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VIDI-grant 917-56-32), Stichting Avanti-STR and NIH grant 5R01CA113454.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cocco C, Pistoia V, Airoldi I. New perspectives for melanoma immunotherapy: role of IL-12. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:459–469. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steitz J, Bruck J, Gambotto A, Knop J, Tuting T. Genetic immunization with a melanocytic self-antigen linked to foreign helper sequences breaks tolerance and induces autoimmunity and tumor immunity. Gene Ther. 2002;9:208–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma A, Li X, Bangari DS, Mittal SK. Adenovirus receptors and their implications in gene delivery. Virus Res. 2009;143:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas JT. Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;36:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuting T, Steitz J, Bruck J, Gambotto A, Steinbrink K, DeLeo AB, et al. Dendritic cell-based genetic immunization in mice with a recombinant adenovirus encoding murine TRP2 induces effective anti-melanoma immunity. J Gene Med. 1999;1:400–406. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199911/12)1:6<400::AID-JGM68>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tormo D, Ferrer A, Bosch P, Gaffal E, Basner-Tschakarjan E, Wenzel J, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of antigen-specific vaccination and toll-like receptor stimulation against established transplanted and autochthonous melanoma in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5427–5435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steitz J, Tormo D, Schweichel D, Tuting T. Comparison of recombinant adenovirus and synthetic peptide for DC-based melanoma vaccination. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:318–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steitz J, Bruck J, Knop J, Tuting T. Adenovirus-transduced dendritic cells stimulate cellular immunity to melanoma via a CD4(+) T cell-dependent mechanism. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkhurst MR, Fitzgerald EB, Southwood S, Sette A, Rosenberg SA, Kawakami Y. Identification of a shared HLA-A*0201-restricted T-cell epitope from the melanoma antigen tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP2) Cancer Res. 1998;58:4895–4901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perricone MA, Claussen KA, Smith KA, Kaplan JM, Piraino S, Shankara S, et al. Immunogene therapy for murine melanoma using recombinant adenoviral vectors expressing melanoma-associated antigens. Mol Ther. 2000;1:275–284. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins PF, Li Y, el-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, et al. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med. 1997;185:453–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Y, Zhang J, Donahue C, Falo LD., Jr Skin-derived dendritic cells induce potent CD8(+) T cell immunity in recombinant lentivector-mediated genetic immunization. Immunity. 2006;24:643–656. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belz GT, Smith CM, Eichner D, Shortman K, Karupiah G, Carbone FR, et al. Cutting edge: conventional CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells are generally involved in priming CTL immunity to viruses. J Immunol. 2004;172:1996–2000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allan RS, Smith CM, Belz GT, van Lint AL, Wakim LM, Heath WR, et al. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8alpha+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science. 2003;301:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.1087576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CM, Belz GT, Wilson NS, Villadangos JA, Shortman K, Carbone FR, et al. Cutting edge: conventional CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells are preferentially involved in CTL priming after footpad infection with herpes simplex virus-1. J Immunol. 2003;170:4437–4440. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. Innate immune response to adenoviral vectors is mediated by both Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. J Virol. 2007;81:3170–3180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huleatt JW, Jacobs AR, Tang J, Desai P, Kopp EB, Huang Y, et al. Vaccination with recombinant fusion proteins incorporating Toll-like receptor ligands induces rapid cellular and humoral immunity. Vaccine. 2007;25:763–775. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akazawa T, Masuda H, Saeki Y, Matsumoto M, Takeda K, Tsujimura K, et al. Adjuvant-mediated tumor regression and tumor-specific cytotoxic response are impaired in MyD88-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:757–764. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheahan T, Morrison TE, Funkhouser W, Uematsu S, Akira S, Baric RS, et al. MyD88 is required for protection from lethal infection with a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000240. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appledorn DM, Patial S, McBride A, Godbehere S, Van Rooijen N, Parameswaran N, et al. Adenovirus vector-induced innate inflammatory mediators, MAPK signaling, as well as adaptive immune responses are dependent upon both TLR2 and TLR9 in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:2134–2144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartman ZC, Kiang A, Everett RS, Serra D, Yang XY, Clay TM, et al. Adenovirus infection triggers a rapid, MyD88-regulated transcriptome response critical to acute-phase and adaptive immune responses in vivo. J Virol. 2007;81:1796–1812. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01936-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philpott NJ, Nociari M, Elkon KB, Falck-Pedersen E. Adenovirus-induced maturation of dendritic cells through a PI3 kinase-mediated TNF-alpha induction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6200–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308368101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Beusechem VW, van Rijswijk AL, van Es HH, Haisma HJ, Pinedo HM, Gerritsen WR. Recombinant adenovirus vectors with knobless fibers for targeted gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1940–1946. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma S, Stolina M, Lin Y, Gardner B, Miller PW, Kronenberg M, et al. T cell-derived IL-10 promotes lung cancer growth by suppressing both T cell and APC function. J Immunol. 1999;163:5020–5028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wexler H. Accurate identification of experimental pulmonary metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1966;36:641–645. doi: 10.1093/jnci/36.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elia L, Aurisicchio L, Facciabene A, Giannetti P, Ciliberto G, La Monica N, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell-inactivation in combination with adenovirus vaccines enhances T-cell responses and protects mice from tumor challenge. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:201–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusser KL, Randall TD. Simultaneous detection of EGFP and cell surface markers by fluorescence microscopy in lymphoid tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:5–14. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samsom JN, van der Marel AP, van Berkel LA, van Helvoort JM, Simons-Oosterhuis Y, Jansen W, et al. Secretory leukoprotease inhibitor in mucosal lymph node dendritic cells regulates the threshold for mucosal tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;179:6588–6595. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweichel D, Steitz J, Tormo D, Gaffal E, Ferrer A, Buchs S, et al. Evaluation of DNA vaccination with recombinant adenoviruses using bioluminescence imaging of antigen expression: impact of application routes and delivery with dendritic cells. J Gene Med. 2006;8:1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/jgm.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okada N, Masunaga Y, Okada Y, Mizuguchi H, Iiyama S, Mori N, et al. Dendritic cells transduced with gp100 gene by RGD fiber-mutant adenovirus vectors are highly efficacious in generating anti-B16BL6 melanoma immunity in mice. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1891–1902. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eggert AA, Schreurs MW, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, de Boer AJ, Punt CJ, et al. Biodistribution and vaccine efficiency of murine dendritic cells are dependent on the route of administration. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3340–3345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheasley-O'Neill SL, Brinkman CC, Ferguson AR, Dispenza MC, Engelhard VH. Dendritic cell immunization route determines integrin expression and lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissue distribution of CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:1512–1522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullins DW, Sheasley SL, Ream RM, Bullock TN, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Route of immunization with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells controls the distribution of memory and effector T cells in lymphoid tissues and determines the pattern of regional tumor control. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1023–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert LA, Gibson GR, Maloney M, Durell B, Noelle RJ, Barth RJ., Jr Intranodal immunization with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells enhances protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:641–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang D, Pereboev AV, Korokhov N, He R, Larocque L, Gravel C, et al. Significant alterations of biodistribution and immune responses in Balb/c mice administered with adenovirus targeted to CD40(+) cells. Gene Ther. 2008;15:298–308. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holst PJ, Orskov C, Thomsen AR, Christensen JP. Quality of the transgene-specific CD8+ T cell response induced by adenoviral vector immunization is critically influenced by virus dose and route of vaccination. J Immunol. 2010;184:4431–4439. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonnotte B, Gough M, Phan V, Ahmed A, Chong H, Martin F, et al. Intradermal injection, as opposed to subcutaneous injection, enhances immunogenicity and suppresses tumorigenicity of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2145–2149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santosuosso M, McCormick S, Xing Z. Adenoviral vectors for mucosal vaccination against infectious diseases. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:283–291. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen K, Cerutti A. Vaccination strategies to promote mucosal antibody responses. Immunity. 2010;33:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noureddini SC, Curiel DT. Genetic targeting strategies for adenovirus. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:341–347. doi: 10.1021/mp050045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setoguchi Y, Jaffe HA, Danel C, Crystal RG. Ex vivo and in vivo gene transfer to the skin using replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus vectors. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:415–421. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12372181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad SA, Norbury CC, Chen W, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Cutting edge: recombinant adenoviruses induce CD8 T cell responses to an inserted protein whose expression is limited to nonimmune cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:4809–4812. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y, et al. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg S, Oran A, Wajchman J, Sasaki S, Maris CH, Kapp JA, et al. Genetic tagging shows increased frequency and longevity of antigen-presenting, skin-derived dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:907–912. doi: 10.1038/ni962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi T, Kawabata K, Koizumi N, Sakurai F, Nakashima K, Sakurai H, et al. Role of MyD88 and TLR9 in the innate immune response elicited by serotype 5 adenoviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:753–762. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y, De Trez C, Flynn R, Ware CF, Croft M, Salek-Ardakani S. The adaptor molecule MyD88 directly promotes CD8 T cell responses to vaccinia virus. J Immunol. 2009;182:6278–6286. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asprodites N, Zheng L, Geng D, Velasco-Gonzalez C, Sanchez-Perez L, Davila E. Engagement of Toll-like receptor-2 on cytotoxic T-lymphocytes occurs in vivo and augments antitumor activity. Faseb J. 2008;22:3628–3637. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahman AH, Cui W, Larosa DF, Taylor DK, Zhang J, Goldstein DR, et al. MyD88 plays a critical T cell-intrinsic role in supporting CD8 T cell expansion during acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 2008;181:3804–3810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quigley M, Martinez J, Huang X, Yang Y. A critical role for direct TLR2-MyD88 signaling in CD8 T-cell clonal expansion and memory formation following vaccinia viral infection. Blood. 2009;113:2256–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartholdy C, Christensen JE, Grujic M, Christensen JP, Thomsen AR. T-cell intrinsic expression of MyD88 is required for sustained expansion of the virus-specific CD8+ T-cell population in LCMV-infected mice. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:423–431. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.004960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]