Abstract

Objectives

Policy-makers rarely consult adolescents during health policy development. However, adolescent perspectives on health can inform public health policies and programs. As part of the development of an Indiana state plan for adolescent health, we used qualitative methods to describe adolescents' “emic” views of health, and discuss implications for a state health policy for youth.

Patients and Methods

We conducted 8 adolescent focus groups in geographically and culturally diverse regions of Indiana. Each group was audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using qualitative methods.

Results

Participants described health as a shared responsibility between adolescents and adults in their lives. They identified a key role for supportive adults in initiating and maintaining health behaviors. Physical, financial, and informational environments could support or hinder healthy behaviors and outcomes. While adolescents' descriptions of physical health and risk behaviors were similar to adult formulations, adolescents described mental health as “stress and fatigue,” an interaction between the adolescent and their environment, rather than depression and anxiety, individual pathologies. Respect for decision-making capacity, seeking adolescent input, and providing harm reduction messages were identified as particularly important.

Conclusions

Adolescent perception of health can inform policies and programs, and should be sought prior to policy development.

Keywords: Adolescence, Health Policy, Youth Development, Qualitative Research, Focus Groups, States, Mental health

Introduction

The health disparities between adolescents and other pediatric groups in unmet health care needs, access to care, and health insurance demonstrate that adolescents are poorly served by current national and state health policies [1-3]. Likely contributing to this disparity is that adolescent health policies frequently focus on individual risk behaviors, rather than broader contextual influences. Not surprisingly, adolescent health programs and practices that focus solely on the individual's responsibility for behavior change (e.g. obesity treatment, suicide prevention, sex education) have had limited success [18-21]. Programmatic failure may be due to not incorporating the views of adolescents, including their own perceptions of health. Qualitative research with diverse adolescent populations, such as Mexican immigrants, gay and lesbian youth, and African young men, has demonstrated that capturing adolescents' “emic” understanding of a health aids in reframing health issues and can lead to greater programmatic involvement [22, 23, 24].

While “disease” is a medical concept, defined by specific diagnostic criteria, “health” is a socially constructed concept [6, 7]. An increasingly prevalent interpretation of health, extends this construct beyond the absence of disease, to include physical, mental, and social well-being, and takes into consideration family, community, and culture [8]. Extending this construct to health policy, policies and programs consistent with a population's social or cultural views of health may be more likely to be accepted, leading to overall improvements in health status. As an example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified 21 Critical Health Objectives for Adolescents from Health People 2010, provides a policy framework where the usual focus on individual risk behaviors is complemented by healthy youth development concepts and health-promoting environments [4, 5].

This study focuses on adolescents' own views of health in an effort to inform state policy. This “emic” approach is consistent with youth development principles [9], taps into ecological models of health that situate youth in families and communities [10], and links health and well being to both individual capacity as well as family and community assets [11]. Ideally, adolescents themselves should participate in the process of defining their relevant health issues and proposing solutions [12, 13]. However, beyond notable exceptions with international health [13, 14], transitioning youth [15], sex education [16], and injury prevention [17], adolescents themselves are rarely consulted in policy formation. In an effort to inform the Indiana Coalition to Improve Adolescent Health's (ICIAH) policy recommendations, we describe Indiana adolescents' views of health and provide implications for state policy.

Methods

Participants

Eight focus groups of 6 to 12 adolescents were recruited from community organizations across the state of Indiana (see table 1). We used a purposive sampling approach to recruit culturally, geographically, and sociodemographically diverse groups where ages ranged from 15-24 years. Participating organizations included Future Farmers of America, a rural alternative high school, urban youth leaders, a Latino student group, a university freshmen class, a program for parenting adolescents, an outpatient drug treatment program, and a private high school. We obtained IUPUI-Clarian Institutional Review Board approval, adolescents' consent and, for minors, parents' permission.

Table 1. Focus Group Participant Demographics.

| Gender | Ethnicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range | Male | Female | White | African American | Latino | |

| Group 1 | 15-18 | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 2 | 19-24 | 5 (55%) | 4 (45%) | 9 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 3 | 17-19 | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 4 | 16-18 | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 5 | 16-18 | 0 (0%) | 8 (100%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 6 | 16-18 | 6 (67%) | 3 (33%) | 8 (89%) | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Group 7 | 16-18 | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) |

| Group 8 | 15-20 | 4 (34%) | 8 (56%) | 10 (83%) | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 34 (50%) | 34 (50%) | 48 (71%) | 13 (19%) | 7 (10%) | |

Procedures

A focus group approach was chosen over individual interviews to: (1) capture the exchange of ideas among participants; (2) assess the degree of consensus and diversity of opinion; and (3) encourage responses with depth and complexity [25]. The facilitator started with a description of the study purpose and focus group procedures. Participants were informed that the purpose was to “gather some information from each of you on your thoughts regarding your health and the health issues that weigh most on your mind at this age,” were told that they could share their own experience, things they have observed or experiences described to them by peers, and were told that they were not expected to reach consensus on issues. They were asked to respect the privacy of others and not to share the discussion outside of the group.

The discussion guide included open-ended questions assessing general health beliefs, health priorities, health information sources, and youth-generated recommendations. Examples included, “What are teenagers health concerns?” “Who do you trust most to go to for health information or advice?” and “What solutions would you recommend to help solve the health issues affecting others your age?” Questions were developed by authors (MO, KM, JR) in collaboration with ICIAH, and piloted with adolescents. The facilitator clarified questions when needed, and encouraged participants to generate ideas and to react to the ideas and statements of others. The one hour sessions were audio-recorded and the facilitator completed field notes. Participants were provided with pizza and a $10 gift card. Theoretical saturation on key topics was reached.

Data Analysis

Textual data were analyzed using a two-stage technique for identifying shared concepts and creating models of social cognitions held by social groups [26, 27]. Interviews and field notes were transcribed and entered into Atlas-ti (version 5.2). Preliminary codes were developed from field notes and an early reading of transcripts. Transcripts were then coded, and each code selected, read and discussed. Key concepts were identified, and a theoretical model was constructed. The process was iterative –data from new focus groups were compared to earlier data, and the model was further refined. We assessed validity and reliability by: (1) testing hypotheses against subsequent data; (2) having two authors (MO, JR) code transcripts and resolve differences by discussion; (3) assessing the theoretical consistency of results; and (4) presenting findings back to youth service providers from ICIAH for review and comment [27-29].

Results

Youth Voice

Participants expressed a desire to have a voice on all levels of decision-making, from state policies to local programs to individual-provider interactions. Participants described feeling engaged when their opinions were sought, and disengaged when their opinions were disregarded. They felt that their experiences should be a part of the planning process:

“Cause a lot of times they say that, but they don't give a shit what we think. They're like ‘Oh this is good for them, let's do this.’ We are different people, we have different thoughts, and we are unique in every aspect of everything.”

19 year old male

The following analyses are based upon this perspective of adolescents as “experts” about their own health.

Conceptual Model: Three Levels of Health

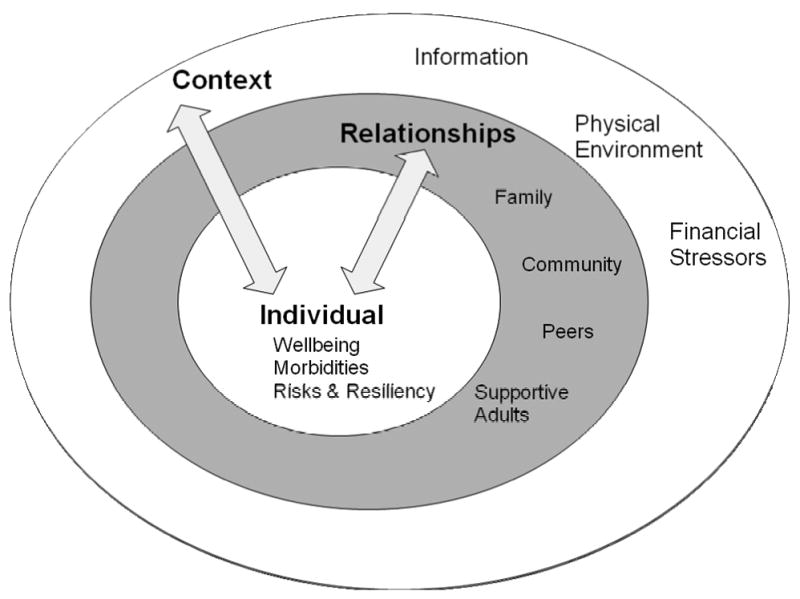

When asked, “What makes a teen healthy?,” all participants initially stated well known risk behaviors and morbidities such as obesity, smoking, drinking, and unprotected sex. However, on further discussion, it became clear that nearly all viewed health as a much broader construct. Across focus groups, we observed three consistent aspects of discussion about health: an individual level, a relationship level, and a contextual level (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Adolescents' Multilevel View of Health.

Individual-Level Factors

At the individual level, participants identified common morbidities and risk behaviors: (1) obesity, (2) stress and fatigue, (3) alcohol, tobacco and substance use, (4) sexual behaviors, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV and adolescent pregnancy, and (5) violence and personal safety. This list was similar to the CDC's 21 Critical Objectives, with two important distinctions.

First, nearly all participants (6 focus groups) highlighted the complex interrelationships between risk and protective factors and morbidities. A participant describes the interplay between alcohol, stress, school, and future aspirations:

“People want to experiment and that's part of your life. But you're being stacked with all this stuff that's supposedly going to be the foundation for the rest of your life. So you're doing things that are gonna take you away from that and then expecting to rise to that occasion at the same time. And, the stress of all that leads some people more in the direction [of alcohol use] because they need a release. It's a balancing act between what you want to do and what you're supposed to do.”

20 year old male

Second, across all focus groups, participants described mental health issues differently. While policy makers focus on depression and anxiety, diseases within individuals [5], adolescent participants described stress and fatigue, an interaction between an individual and their environment. A participant describes juggling school and work:

“….you don't ever get a break. It's a constant stress….like oh I have to get this done. Oh, but that's done now I have to get this done. It's like so like, draining and you just drone on in the same sort of like, deadlines….it really does mess with you.”

19 year old male

Relationships

Supportive relationships with family, schools and community members were considered necessary to initiate and maintain healthy behaviors, and to create a healthy environment. These relationships provided a connection, remained positive and non-judgmental, and respected the adolescent's evolving abilities. A participant describes the importance of adult support for losing weight:

“Someone to help motivate them, keep them going, cause after awhile you just get burnt out on it. You don't have anyone motivating you and….[exercise and sticking to a diet] just gets boring and everything”

17 year old male

An adult who provided a connection talked about difficult issues, lived through similar life experiences (e.g. poverty, drug use, school failure), and expressed an interest in listening to adolescent's issues:

“I have a pastor at my church that's really good… he was the rock n' roll type, you know the partying type. He finally turned his life around. He helps all of the youth at our church. Any kind of problems they have got, he has been through it.”

16 year old male

Participants also differentiated adults willing to “talk with” adolescents as opposed to “talk to” them.

It was important for adults to be positive and non-judgmental. All participants spoke of the importance of feeling valued and having adults encourage their self worth. Examples ranged from receiving a simple compliment to being provided with feedback without being criticized. Participants were particularly sensitive to stigma and shame, as illustrated by this parenting adolescent's description of a teacher who commented on her decision to have a child:

“I mean, like don't use your personal judgment on my schooling. When I'm in school that's my focus. Yeah, I have a kid, but I'm here to learn….Your job is to teach me. You're not getting paid to criticize me about having a kid at my age.”

16 year old female

A third characteristic was respect for adolescents' evolving decision-making capacity, especially as it related to the healthcare setting. Adolescents who were able to provide input into their treatment described being more invested and engaged:

“At the counseling center they totally give you the option. Do you wanna be prescribed something or do you wanna go a different route? I totally said different route. The stuff they worked on, like breathing techniques and stuff, I feel totally work a lot better than just being put on something.”

19 year old female

In contrast, when adolescents' input and preferences were not acknowledged, participants described feeling disengaged from provider and their treatment.

Parents were considered the most important people in supporting healthy decision-making and outcomes. Criticism was acceptable, if the parents remained supportive:

“If your parents or your friends they support you, they basically have your back. Or they don't have your back, and they should give you positive criticism if criticism is needed. Nobody wants to be down all the time. You need that type of support and encouragement.”

17 year old male

Peers, teachers, and other adults were called upon in situations where the parent was unable to provide support, or the adolescent was uncomfortable asking. Topics generally involved relationships, sex, contraception, or substance use.

Participants varied in the amount of responsibility they placed upon an individual for their own behaviors and health, versus the responsibility they placed upon adults and environments. Conversations with some participants (particularly those from higher income groups) reflected a tension between the individual versus the collective responsibility. Here a participant recognizes individual responsibility, but also the important role of adult support, regardless of poor decision-making on the part of the adolescent:

“The way she talks to you, she keeps it real. She be like ‘You do this, you do this you gonna have these consequences. But if you need somebody even if you make a mistake, you can come to me.’ See, people don't say that, they just tell you your mistake and your consequence.”

17 year old female

Environment and Contexts

All focus groups identified their environments, i.e, physical, financial and informative as critical to initiating and maintaining healthy behavior.

Physical Environment

The physical, or built, environment included the structure of, and the way people use neighborhoods, schools, buildings, roads, and green-space. Participants described their physical environment as either health promoting or inhibiting. One participant described safety concerns walking between home and work:

“I used to live close to my job and I didn't have a car so I would walk over there but I didn't like it because there were no sidewalks. I had to walk on top of the grass.”

16 year old female

Participants linked the presence or absence of a physical environment conducive to exercise and with access to healthy foods to obesity. Lower income participants described a lack of green space and public transportation, little access to grocery stores or restaurants with healthier food options and physically unsafe neighborhoods.

Participants who lived in areas marked by violence and crime, described risks of physical injury, emotional stress, and lack of physical activity as characteristics of the environment with multiple impacts on health. A 17 year old male describes the limitations of this type of environment for those not directly involved in violence:

“I used to stay outside past a certain hour, but thanks to people around my neighborhood, stayin' outside went out the window. People stay on the Internet all the time.”

17 year old male

Financial and Other Resources

Resources included family income, neighborhood and school amenities, and access to health care. Like the physical environment, participants identified their families' financial contexts as health promoting or inhibiting. Several participants described needing to work to contribute to family income or to support themselves. Several described time and stress related to this:

“If you're working however many jobs and school and everything, you don't have time to make healthy foods…You throw a hot pocket in the microwave before you leave for work.”

16 year old male

Others described parents working long hours and having no-one at home to cook meals or provide support.

Access to health insurance and quality health care providers were identified as important resource issues. Some participants mentioned only having access to emergency departments. Others said that cost was a barrier to necessary services. A college freshman said,

“When I turned eighteen I didn't have [Medicaid] anymore. If I go to the doctor I pay. The only reason I have any coverage is because my mom gets a little bit of insurance through work. So most of the time I'm sick I don't go to the doctor.”

Informational Environment

Participants described concern the health information provided by schools, programs, parents and other adults. They placed a priority on honesty and truthfulness, and described multiple scenarios in which they felt that honesty and truth-telling had been compromised. Participants were skeptical of over-simplified messages around sexual behavior, drugs, and alcohol use, and generally felt that harm-reduction approaches were most appropriate. “Just say no” approaches were felt to be unhelpful, and did not reflect the complex reality of alcohol and drug use among adolescents:

“I mean, you can tell them it's better to just not [drink], but I think the best way, especially in our generation, is to teach them how to be safe while they're doing something like that. Not to do stupid stuff.”

16 year old male

Respect for youth and their decision-making capacity was perceived to be important. Participants wanted to be treated in a serious, respectful way:

“Last year, this family came [to school] and juggled and did circus acts, and then they're like, “Don't have drugs! So you can do what we do.” I think it was almost worse than actually helpful. I think it's better for someone to just be serious with them, someone from a town or a place like theirs and just be serious and talk to them.”

17 year old male

Comments were similar for information about sex, pregnancy, and STIs. Participants preferred harm reduction approaches that acknowledge the reality of adolescent sexual behavior. They described the need for information and skills, instead of scare tactics:

“They say you need to be abstinent but it doesn't help. They should spend more time showing how to do it safely instead of saying not to do it.”

16 year old male

Most participants expressed a preference for a complex harm reduction message over a simple proscriptive message. This participant felt that sex education should acknowledge the positive aspects of sex as well as the risks:

“Yeah, keep it real…I hate when people be like ‘don't have sex, it is not for you’. I want someone to tell me sex is ok, but if you do this make sure that you do it this way. I am for real, say sex is good just wrap it up.”

18 year old female

Participants were attuned to contradictory health messages. This is illustrated by several participants' observations that many schools allow soda machines, but advise against soda in their health curricula:

“You see it, you walk around the school. They say ‘Oh, you guys can't buy sodas,’ but there are soda machines everywhere. Why would they have them if they don't want us to buy them?”

16 year old female

Discussion

These data demonstrates how understanding adolescents' own views of health can inform policies and programs. The use of adolescent focus groups tapped into an “emic” perspective, and interactions among participants facilitated a deeper and more complex discussion [25]. Three specific findings are of importance to adolescent health policy.

First, mental health was an area in which current policy approaches are at odds with adolescents' experiences. For example, two adolescent mental health objectives are to reduce the suicide rate and to increase access to treatment [5]. However, ourparticipants did not view mental health as individual pathologies such as depression or anxiety; instead they viewed mental health as an interaction between the individual and his or her environment. From this perspective, prevention and treatment need to go beyond individual engagement in mental health services, and include a focus on healthier environments.

Second, participants viewed health as a shared responsibility between the adolescent and adults in their lives. Supportive relationships and healthy physical, financial and informational environments were considered necessary to support healthy behaviors and outcomes. In areas ranging from food choices to drug and alcohol use to health care, participants pointed out that many times their current environment, family or school contexts promoted unhealthy behaviors. While these observations are not new, this structural need for supportive adults and environments is not frequently addressed through policies. For example, obesity and tobacco interventions typically focus heavily on individual adolescents changing their own behaviors. Few focus on modifying home and school environments, such as the availability of healthy food choices, increased opportunities for physical activity, or less exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

Finally, across socio-demographic groups, participants overwhelmingly supported truthfulness and harm reduction in health education, particularly in sensitive areas such as alcohol, substance use, and sexual behavior. Participants believed that adolescents were capable of handling complex health education messages. These findings are consistent with data, such as evaluations of sex education programs, demonstrating the effectiveness of comprehensive and harm-reduction approaches over abstinence-only approaches [18, 30, 31]. They are also consistent with ethical approaches to public health, which eschew the withholding of information needed to make decisions about health [32].

These findings should be interpreted in the contexts of strengths and weaknesses in the study design. We used a purposive sampling approach, including adolescents from different geographic locations, age groups, and ethnic backgrounds. While participants spanned a wide range of ages and life experiences, we observed remarkable consistency across groups. The one major exception was that participants ages 18 and over expressed high levels of concern about health insurance and access to care. However, we recognize that some groups of adolescents were not included, and that the views expressed may not be representative of all adolescents. We also note that adolescents in our study were only involved in a very basic level of policy making, gathering perspectives and identifying priorities, and were not involved in higher levels of policy development and decision making [33].

Strengths include the consistency of our findings with existing research. For example, participants' belief in the importance of connection to a caring adult is consistent with nationally representative data demonstrating that parent, family and school connectedness are protective against a variety of health risks [34]. Another strength was our capacity to tap into participants' concern about their health and interest in participating in these discussions. These adolescents' ‘lived experiences’ provided the perspective needed for health providers and policy makers to create an environment in which adolescents can thrive.

Acknowledgments

The information in this paper represents the views of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the views of the Indiana State Department of Health.

Abbreviations

- STI

Sexually Transmitted Infection

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Callahan ST, Cooper WO. Uninsurance and Health Care Access among Young Adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2005;116:88–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newacheck PW, Park MJ, Brindis CD, et al. Trends in Private and Public Health Insurance for Adolescents. Jama. 2004;291:1231–1237. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Park MJ, et al. Disparities in Adolescent Health and Health Care: Does Socioeconomic Status Matter? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1235–1252. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Adolescent and School Health, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Office of Adolescent Health & National Adolescent Health Information Center University of California, San Francisco. Improving the Health of Adolescents and Young Adults: A Guide for States and Communities. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park MJ, Brindis CD, Chang F, et al. A Midcourse Review of the Healthy People 2010: 21 Critical Health Objectives for Adolescents and Young Adults. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nettleton S. The Sociology of Health and Illness: Polity. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seedhouse D. Health: The Foundations for Achievement. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36:1315–1323. doi: 10.2105/ajph.36.11.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton SF, Hamilton MA, Pittman K. Principles for Youth Development. In: Hamilton SF, Hamilton MA, editors. The Youth Development Handbook: Coming of Age in American Communities. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-Nurture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model. Psychol Rev. 1994;101:568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youngblade LM, Theokas C, Schulenberg J, et al. Risk and Promotive Factors in Families, Schools, and Communities: A Contextual Model of Positive Youth Development in Adolescence. Pediatrics. 2007;119 1:S47–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernat DH, Resnick MD. Healthy Youth Development: Science and Strategies. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;(Suppl):S10–16. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Percy-Smith B. ‘You Think You Know? … You Have No Idea’: Youth Participation in Health Policy Development. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:879–894. doi: 10.1093/her/cym032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wills WJ, Appleton JV, Magnusson J, et al. Exploring the Limitations of an Adult-Led Agenda for Understanding the Health Behaviours of Young People. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16:244–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiss JG, Gibson RW, Walker LR. Health Care Transition: Youth, Family, and Provider Perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115:112–120. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Advocates for Youth. Youth Action Center. 2009 [cited 2009 January 30]; Available from: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/youth/advocacy/yan/index.htm.

- 17.Monneuse OJ, Nathens AB, Woods NN, et al. Attitudes About Injury among High School Students. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Washington, D.C.: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamath CC, Vickers KS, Ehrlich A, et al. Clinical Review: Behavioral Interventions to Prevent Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review and Metaanalyses of Randomized Trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4606–4615. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGovern L, Johnson JN, Paulo R, et al. Clinical Review: Treatment of Pediatric Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4600–4605. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide Prevention Strategies: A Systematic Review. Jama. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper GW, Jamil OB, Wilson BDM. Collaborative Community-Based Research as Activism: Giving Voice and Hope to Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Routledge; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izugbara CO. Masculinity Scripts and Abstinence-Related Beliefs of Rural Nigerian Male Youth. Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45:262–276. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia CM, Saewyc EM. Perceptions of Mental Health among Recently Immigrated Mexican Adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28:37–54. doi: 10.1080/01612840600996257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan DL. Annual Reviews. 1996. Focus Groups. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Andrade RG. The Development of Cognitive Anthropology. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirk J, Miller ML. Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert H, McKevitt C. Anthropology in Health Research: From Qualitative Methods to Multidisciplinarity. Bmj. 2002;325:210–213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trenholm C, Devaney B, Fortson K, et al. Impacts of Four Title V, Section 510 Abstinence Education Programs, Final Report. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Underhill K, Montgomery P, Operario D. Sexual Abstinence Only Programmes to Prevent Hiv Infection in High Income Countries: Systematic Review. Bmj. 2007;335:248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39245.446586.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santelli JS. Medical Accuracy in Sexuality Education: Ideology and the Scientific Process. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1786–1792. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnstein A. A Ladder of Citizenship Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 1969;26:216–233. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting Adolescents from Harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Jama. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]