Abstract

Objective

To determine if the metronidazole (MTZ) 2 gm single dose (recommended) is as effective as the 7 day 500 mg BID dose (alternative) for treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) among HIV+ women.

Methods

Phase IV randomized clinical trial; HIV+ women with culture confirmed TV were randomized to treatment arm: MTZ 2 gm single dose or MTZ 500 mg BID 7 day dose. All women were given 2 gm MTZ doses to deliver to their sex partners. Women were re-cultured for TV at a test-of-cure (TOC) visit occurring 6-12 days after treatment completion. TV-negative women at TOC were again re-cultured at a 3 month visit. Repeat TV infection rates were compared between arms.

Results

270 HIV+/TV+ women were enrolled (mean age = 40 years, ± 9.4; 92.2% African-American). Treatment arms were similar with respect to age, race, CD4 count, viral load, ART status, site, and loss-to-follow up. Women in the 7 day arm had: lower repeat TV infection rates at TOC [8.5% (11/130) versus 16.8% (21/125) (R.R. 0.50, 95% CI=0.25, 1.00; P<0.05)], and at 3 months [11.0% (8/73) versus 24.1% (19/79) (R.R. 0.46, 95% CI=0.21, 0.98; P=0.03)] compared to the single dose arm.

Conclusions

The 7 day MTZ dose was more effective than the single dose for the treatment of TV among HIV+ women.

Keywords: Trichomonas vaginalis, HIV-infected women, metronidazole

INTRODUCTION

Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), the most common curable sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide 1, has been associated with vaginitis, cervicitis, urethritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease in women.2 TV infection in HIV-infected women may enhance HIV transmission by increasing genital viral shedding 3-7 and successful treatment for TV has been shown to reduce shedding 8, 9, suggesting that effective TV treatment could play a preventative role in perinatal and sexual HIV infection.4

Post-treatment repeat TV infection rates among HIV-positive women have been shown to be higher (18-36%) 10-12 than among HIV-negative women (7-8%).13-15 While these studies had variable lengths of follow-up time, a comparison of two studies that rescreened at one-month found that repeat TV infections were two-fold higher among HIV-positive women compared to HIV-negative women12 indicating that the phenomenon is real. This study also found that the most likely cause of repeat infections for both groups was treatment failure and that the treatment failure was most likely attributable to host factors rather than organism resistance to the drug metronidazole (MTZ).12

The recommended treatment regimens for TV from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention include: MTZ 2 gm oral single dose; or tinidazole 2 gm oral single dose.16 The alternative treatment regimen is MTZ 500 mg orally twice a day (BID) for 7 days.16 The studies supporting the use of the single 2 gm MTZ dose as the primary treatment regimen, however, were conducted with mostly non-HIV infected women.17-24 Given the high rates of repeat infections, and the mounting evidence that many of these repeat infections are due to treatment failure, the MTZ 2 gm single dose may not be adequate for HIV-infected women. The purpose of this randomized trial was to determine if the recommended MTZ 2 gm single dose is as effective as the alternative 7 day 500 mg BID dose for treatment of TV among HIV-infected women.

METHODS

Participants

HIV-infected women undergoing a routine gynecological examination performed by a clinic health care provider between May 1, 2006 and July 17, 2009 were tested for TV by culture as standard of care practice. Women were patients attending selected public HIV outpatient clinics in New Orleans, Louisiana; Houston, Texas; and Jackson, Mississippi. The clinics were selected based on prior collaborations between investigators and clinic health care providers.

Eligibility

Women were considered eligible for study participation if they were HIV-infected (confirmed by Western Blot), ≥ 18 years of age, English speaking, positive for TV by culture, willing to take MTZ treatment, and agreed to refrain from drinking alcohol 24 hours after taking MTZ. Women were excluded from participation if they were pregnant, incarcerated, taking disulfiram, or treated with MTZ within the previous 14 days. Other exclusion criteria, per provider discretion, were: diagnosis of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis which would require 7 day MTZ treatment, medical contraindications to MTZ, or unable to provide informed consent.

Randomization

Randomization allocation was done, by site, in blocks of four and six using SAS version 9.0. Sealed, numbered envelopes containing treatment assignment were prepared in advance and opened at enrollment. A list of arm by study number was kept sealed in the principal investigator’s office for quality assurance.

Baseline examination

During the routine gynecological examination, the provider assessed the woman’s vaginal discharge for amount, color, and consistency. The following specimens were obtained by the provider in this order: 1) four vaginal swabs for TV culture, wet preparation, “whiff test” using potassium hydroxide (KOH), and Gram stain testing (processed after enrollment), 2) endocervical brush/spatula for pap smear, and 3) endocervical swab for chlamydia and gonorrhea. A vaginal pH was obtained from secretions after speculum removal. The wet preparation was examined by the provider for TV, clue cells, and candidiasis. The “whiff test”, vaginal pH, and wet preparation were conducted by the provider as part of the assessment for bacterial vaginosis using Amsel criteria. If the wet preparation was positive for TV, women were enrolled immediately and culture results were used as confirmation. If only the culture was positive, women were called back to the clinic for enrollment.

InPouch Culture

Participants were tested for TV using the InPouch culture technique (InPouch - Biomed Diagnostics; White City, Oregon). Vaginal swabs were obtained by the provider during the baseline examination. At the follow-up visits, most vaginal swabs were obtained by participant self-swab. Some swabs were obtained by the provider if the woman’s study visit coincided with her regular clinic visit. A comparison of self-collected vs. provider collected vaginal specimens have shown similar predictive values for TV diagnosis.25 For the self-swab, the woman was asked to insert a swab into the vagina similar to tampon insertion, rotate the swab three times around the vaginal cavity, remove the swab, and place in a clear plastic tube which was then given to study staff.

Vaginal swabs were placed into the culture pouch and agitated to release adherent organisms following the manufacturer’s protocol. Pouches were examined under the microscope for TV by trained study staff immediately upon receipt. The culture was then placed in an incubator with a regulated temperature of 37° C. Per manufacturer protocol, study staff obtained three daily readings within a five-day period. A diagnosis of TV was made after the first positive pouch reading. After three negative pouch readings, the woman was considered TV-negative.

Survey

At each study visit, a survey was conducted using audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) format which was based on previous survey instruments used among HIV-infected women.9, 12 If participants were unable to use the computer, or unable to read, the study staff provided assistance or administered the interview using either a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) or paper-to-pen format.

The baseline survey, which was conducted after the gynecological exam but before randomization to treatment, elicited detailed information about participants’ demographics, socio-economics, HIV history, STI risk behavior, substance use, and birth control methods, as well as partner specific information about sexual behavior, disclosure of HIV status, condom usage, and partnership status. Partner specific information was linked from visit to visit by the identifying initials of each partner reported by the participant on the baseline survey. Study staff abstracted information from the participant’s clinic chart about the type of prescribed antiretrovirals, CD4 cell count, and viral load at the baseline visit.

The follow-up surveys conducted at TOC and 3 months asked detailed information about participant treatment adherence, delivery of treatment to partner(s), sexual exposure with baseline or new partners, and participant or partner symptoms.

Treatment

Generic MTZ tablets were supplied by pharmacies at each site according to the pharmacy’s protocol. According to randomization, participants assigned to the single dose arm were given the MTZ 2 gm dose (4 pills) under direct observation by the study coordinator. The participant was asked to remain at the clinic for 30 minutes to monitor for vomiting. Participants randomized to the 7 day arm were given the MTZ 500 mg BID dose (14 pills) and the first pill was given under direct observation. To prevent nausea, snacks were provided upon request. Since this was an effectiveness trial (i.e. benefit under real world conditions) rather than an efficacy study (i.e. benefit under ideal circumstances) with an objective end point (i.e. TV culture), a double-blind study design was not used.

Counseling

All participants received the same counseling: to refrain from unprotected sexual intercourse until they and their partner(s) completed the medication, to refrain from alcohol consumption while taking the medication and for 24 hours after completion. Participants were informed of the potential to experience MTZ-related adverse events including dizziness, headache, diarrhea, nausea, upset stomach, and change in taste sensation or dry mouth, and were advised that MTZ can cause a discoloration of urine. Participants in the 7 day treatment arm were also given additional counseling on the importance of taking all doses of the medication.

Partner treatment

Participants in both treatment arms were provided with MTZ 2 gm single doses to deliver to their sex partner(s) 26, i.e. patient-delivered partner treatment (PDPT), a form of expedited partner therapy (EPT). The medication was dispensed in a child-proof container, with clear and visible instructions to take the medication with food and to avoid drinking any alcohol for 24 hours after taking the medicine. Additionally, a medication instruction sheet for MTZ was provided with each PDPT dose, reiterating the warnings on the medication container as well as with warnings not to take the medicine if the partner was taking disulfiram, was allergic to MTZ, had liver problems, or was unable to refrain from alcohol use. If any warnings were true, the participant was instructed to tell her partner to seek care from their personal health care provider or local STD clinic. Participants were given a 24-hour pager number for the study coordinator in case she or any partners had questions.

Follow-up

A TOC visit was scheduled for 6-12 days after the index woman completed her medication dose, with an allowed window of 8 weeks after enrollment. Women who tested positive for TV at the TOC visit were considered an early repeat infection, most likely due to treatment failure.12, 26 Women who tested negative for TV at the TOC visit, or who did not complete a TOC visit, were scheduled for a follow-up visit at 3 months after enrollment with an allowed window of 8-18 weeks. The 3 month timeframe was chosen to coincide with routinely scheduled clinic appointments. The rationale for including the 3 month visit as a secondary outcome in the evaluation of the treatment trial was twofold: 1) some women would not attend the TOC visit and 2) the potential for false negatives at TOC. The sensitivity of InPouch TV culture compared to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is only 70-78%.27-29 Thus, treatment-induced low concentrations of viable organisms at the time of the TOC visit may have been below the limit of culture detection.30 If such were the case, it would be anticipated that renewed growth would occur over time, enhancing the chance of detection by culture at a later follow-up visit.

Women who tested positive for TV at either follow-up visit (TOC or 3 months) were referred to their clinic provider for further treatment and this information was documented in their clinic records.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

It was initially estimated that a total of 380 participants (190 per arm) would be required, with 90% power and a significance level of 5%, to establish equivalency between the two treatment arms.31 Enrollment rates were lower than estimated and only 270 participants (135 per arm) were enrolled.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1. Continuous variables were assessed for normality, and tested accordingly. When appropriate, continuous variables were categorized using clinically relevant cut-points. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. The measure of association at TOC and 3 months was calculated as a relative risk with 95% confidence interval.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the clinical sites, and all women gave written informed consent before randomization. Participants received the following incentives for study visit completion: $25 gift card at baseline; $50 gift card at TOC and 3 months. While side effects were closely monitored, no interim analysis was performed as this was a phase IV trial.

RESULTS

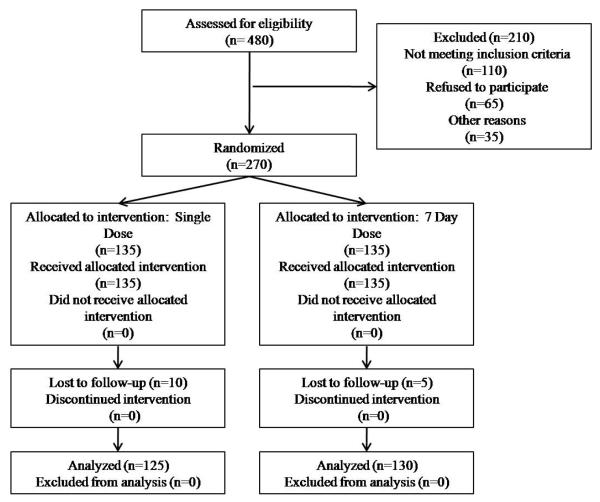

A total of 2,833 screenings were conducted among HIV-infected women from all participating clinics, with 16.9% testing TV-positive (n=480). Of the 480 TV+ women, 110 were ineligible, 65 refused study participation, and 35 women could not be contacted by study staff. A total of 270 women were enrolled in the study (Figure 1): 60.7% were positive for TV by wet preparation and culture (n=164); 39.3% were positive for TV by culture only (n=106).

Figure 1.

Enrollment Flow Chart

Baseline characteristics

The 270 participants (HIV+/TV+ women) had the following enrollment distribution: 129 in Houston (47.8%), 74 in New Orleans (27.4%), and 67 in Jackson (24.8%). The majority of participants (92.2%) were African-American (n=249), and the mean age was 40.1 years (±9.4). Over half of the participants (65.2%, n=176) were on antiretroviral therapy (ART), 29.6% had a CD4 cell count ≤ 200 mm3 (n=80), and 35.6% had a plasma viral load >10,000 copies (n=96). Of the participants with CD4 cell counts ≤ 200 mm3, 21.3% were not on ART (n=17). Only 28.5% of the participants were married or cohabitating (n=77), 42.2% reported not graduating high school (n=114), and 69.6% reported being unemployed (n=188). The most common symptom in the week before the baseline visit reported by the women was unusual vaginal discharge (45.2%, n=122), followed by unusual vaginal itching or irritation (43.3%, n=117), unusual vaginal odor (34.1%, n=92), pelvic pain (14.8%, n=40), and painful urination (13.0%, n=35). Some women were asymptomatic and reported no vaginal problems in the past week (31.5%, n=85).

Most participants reported having a history of yeast infection at least once in the past (76.7%, n=207), and 41.5% reported a history of TV (n=112). The self-reported history of ever having other infections is as follows: gonorrhea 26.7% (n=72), Chlamydia 25.2% (n=68), syphilis 24.8% (n=67), genital warts 22.2% (n=60), genital herpes 21.9% (n=59). History of bacterial vaginosis was 12.2% (n=33). From the baseline gynecological examination, Chlamydia and gonorrhea results were available for 240 women, with 2.5% (n=6) and 1.7% (n=4) testing positive respectively.

In the three months before baseline, 22.2% of participants reported not having any sex partners (n=60), 62.2% had one sex partner (n=168), 14.8% had two or more sex partners (n=40), and 0.7% did not respond to the question (n=2). Of the 208 participants with partners, the majority had male sex partners (95.2%, n=198), with 7 participants having male and female partners (3.4%) and 3 participants having only female partners (1.4%).

Baseline characteristics by arm

As randomized, 135 participants received the MTZ 2 gm single dose, and 135 participants received the MTZ 7 day 500 mg BID dose. There were no differences found between arms with respect to age, race, having ≥1 sex partner, TV-related symptomatology, CD4 count, viral load, ART status, ART status for those with CD4 cell counts ≤ 200, or enrollment site (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of HIV+/TV+ Women by Metronidazole Treatment Arm (N=270)

| Single dose (n=135) |

7 day dose (n=135) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 40 years of age | 50.4% | 50.4% | 1.00 |

| African-American | 91.9% | 92.6% | 0.99 |

| ≥1 sex partner in past 3 months | 77.0% | 77.0% | 1.00 |

| TV-related symptomatology in past week | 66.7% | 70.4% | 0.51 |

| On ART | 65.2% | 65.2% | 1.00 |

| CD4 cell count ≤ 200/mm3 | 24.8% | 35.1% | 0.07 |

| On ART | 18.2% | 23.4% | 0.57 |

| Plasma viral load >10,000 copies | 37.9% | 34.6% | 0.58 |

| Enrollment Site | 0.96 | ||

| New Orleans HOP clinic (n=66) | 25.2% | 23.7% | |

| New Orleans NOAIDS clinic (n=8) | 2.2% | 3.7% | |

| Jackson Crossroads clinic (n=67) | 24.4% | 25.2% | |

| Houston Thomas St. clinic (n=108) | 40.0% | 40.0% | |

| Houston Northwest clinic (n=21) | 8.2% | 7.4% |

TOC visit

A total of 255 participants returned for the TOC visit, including 125 from the single dose arm and 130 from the 7 day arm. There were no differences found between women who completed a TOC visit (n=255) and women who did not return for this visit (n=15) with respect to age, race, CD4 count, viral load, ART status, enrollment site, or arm. The majority of women (64%) were interviewed using ACASI, whereas 36% were interviewed by study staff. There were no differences in method of interview by arm or by site. The median time interval from baseline to the TOC visit for the single dose arm was 7 days, and for the 7 day arm was 14 days (p<.0001). This difference was expected given the duration of treatment for each arm.

Partner treatment and sexual exposure at TOC

Of the 208 participants with partners at baseline, 201 returned for the TOC visit, and 76.1% reported giving the partner treatment to all of their partners (n=153). There were no differences found between arms for delivery of partner treatment [74.0% (71/96) in the single dose arm and 78.1% (82/105) in the 7 day arm reported giving the medication to all partners; p=0.49]. At TOC, 16.1% of participants reported sexual exposure to baseline partners and/or new partners since the baseline study visit (41/255) and there were no differences in the rate of sexual exposure by arm [19.2% (24/125) in the single dose arm versus 13.1% (17/130) in the 7 day arm; p=0.18].

Adverse events and treatment compliance at TOC

Overall, 96.1% of participants reported taking all of their MTZ treatment as instructed (n=245). A majority of participants (60.4%) reported no adverse events secondary to MTZ (n=154). The most common adverse event reported was nausea and/or upset stomach (n=65, 25.5%) followed by headache (n=22, 8.6%), dizziness (n=22, 8.6%), and vomiting (n=12, 4.7%). A few participants reported altered taste sensation (n=6) or itching/rash (n=9).

There were no differences found between arms with respect to index treatment adherence and side effects (Table 2). Treatment adherence for the single dose arm was not reported to be 100% because a few women were under time constraints at their baseline visit and unable to stay for 30 minutes of observation. In these instances, women were provided the single dose treatment to take later that day.

Table 2.

Treatment Adherence and Side Effects by Metronidazole Treatment Arm at Test-of-Cure Visit (N=255)

| Single dose (n=125) % |

7 day dose (n=130) % |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index reported taking all treatment as instructed |

97.6% | 94.6% | 0.33 |

| No reported reaction to MTZ | 63.2% | 57.7% | 0.37 |

| Reported nausea or upset stomach | 22.4% | 28.5% | 0.27 |

| Reported headache | 7.2% | 10.0% | 0.43 |

| Reported dizziness | 8.0% | 9.2% | 0.73 |

| Reported vomiting | 4.0% | 5.4% | 0.60 |

TV culture results at TOC

Of the 255 participants at TOC, 32 (12.5%) tested positive for TV (Table 3). In the 7 day arm, 8.5% tested positive for TV (11/130), and in the single dose arm, 16.8% tested positive for TV (21/125). Women in the 7 day arm were half as likely to test positive for an early repeat TV infection compared to women in the single dose arm [R.R. 0.50 (95% CI=0.25, 1.00; P=0.045)].

Table 3.

T. vaginalis Results by Metronidazole Treatment Arm at Test-of-Cure (N=255) and 3 Month (N=152) Visits

| TV+ Rate Overall % (n) |

7 day dose % (n) |

Single dose % (n) |

RR (95% CI) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOC | 12.5% (32/255) |

8.5% (11/130) |

16.8% (21/125) |

0.50 (0.25, 1.00) |

0.045 |

| 3 month | 17.8% (27/152) |

11.0% (8/73) |

24.1% (19/79) |

0.46 (0.21, 0.98) |

0.030 |

RR=Relative Risk; CI=Confidence Interval

3 month visit

From the 223 participants who were TV-negative at TOC, 149 returned for a 3 month visit. There were six participants who did not attend the TOC visit but completed a visit at 3 months. There were no differences found between women who completed a 3 month visit (n=155) and women who were lost-to-follow-up at 3 months (n=83) with respect to race, CD4 count, viral load, ART status, enrollment site, or treatment arm. Women who were lost-to-follow-up were younger than women who completed a 3 month visit, with respective mean ages of 38.5 and 41.3 years (p=0.03).

Three participants reported taking MTZ since the baseline visit and were excluded from the analysis. Of 152 participants seen at the 3 month visit, 79 were in the single dose arm and 73 were in the 7 day arm. The median time intervals from baseline to the 3 month visit were 91 and 90 days for the single dose arm and for the 7 day arm respectively (p=0.44). Just over half of the participants (53.9%) reported sexual exposure to baseline partners and/or new partners since their last study visit (n=82), and the rates of sexual exposure did not differ between arms [57.0% (45/79) in the single dose arm versus 50.7% (37/73) in the 7 day arm; p=0.44].

TV culture results at 3 months

Of the 152 participants at 3 months, 27 (17.8%) tested positive for TV (Table 3). In the 7 day arm, 11.0% (8/73) tested positive for TV compared to 24.1% (19/79) in the single dose arm. Women in the 7 day arm were half as likely to test positive for a repeat TV infection compared to women in the single dose arm [R.R. 0.46 (95% CI=0.21, 0.98 ; P=0.03)].

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of treatment for TV among HIV-infected women. The strengths of the study include a multi-centered design, with a high follow-up rate at TOC (94.4%), and an objective endpoint (i.e. TV culture) with two follow-up measures. At TOC, the 7 day 500 mg BID MTZ dose resulted in significantly lower repeat TV infections compared to the 2 gm single MTZ dose in this group of HIV-infected women. Additionally, there were no differences found between arms for treatment adherence and side effects, making the 7 day dose just as acceptable as the single dose. Given the known potential for false negatives at a TOC visit, we also examined treatment differences at the 3 month visit as a secondary outcome and found results consistent with the TOC results indicating treatment superiority for the 7 day dose of MTZ.

Despite the strong study design, there are some potential limitations. The goal of the study was to determine treatment effectiveness (real world), not efficacy (under ideal conditions), thus a double-blind study design was purposely not utilized. It is possible, therefore, that the treatment advantage in the 7 day arm could be attributed to women re-initiating sex later than women in the single dose arm. This possibility is unlikely given the fact that the rates of sexual exposure at TOC and 3 months were similar by randomization arm and both arms were retested 6-12 days post completion of treatment, the time women were at highest risk for possible for re-infection via exposure to an original partner or exposure to a new partner were similar. In addition, both arms reported high adherence to self-treatment and partner treatment, re-exposure was likely minimal.26 While it is possible that self-reports of sexual exposure and partner treatment could be inaccurate, there is no reason to believe this potential error would differ by treatment arm. In addition, the use of audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) format for the survey likely reduces potential interviewer and social desirability biases. Furthermore, the percentage opting for self-administered interview vs. staff administered did not vary by arm at TOC.

While this study assumes that most of the repeat infections are due to re-infection, it is possible that these infections are organism-related rather than host-related. However, this is unlikely that this possibility impacted the findings of the study for two reasons. Even though the prevalence of MTZ-resistant TV may be on the rise 32, studies of clinical TV isolates have found nonsusceptibility rates to be low at 2.2-9.6%.33-35 Furthermore, since women were randomized to treatment, organism differences were likely distributed even by arm. This suggests that the high rate of single dose treatment failure found among HIV-positive women is more likely attributable to host factors rather than to organism-related factors.

The screening prevalence of TV for this study (17%) is in the range of previously described TV rates among HIV-infected women (11-30%) 36-39 but the TOC repeat infection rate (12.5%) was lower compared to those described in the literature (18-36%).10-12 These differences are likely due to longer follow-up intervals in the older studies, differences in partner treatment approaches (providing or not providing patient-delivered partner treatment), and/or false negatives because of our early rescreening time and the possibility of persistent but culture undetectable infections.30, 40

Generalizability is always a concern in clinical trials. The demographics of our study population (i.e. HIV+/TV+ women from three southern cities in the United), while slightly more likely to be African American (92.2% vs. 60.6%) and ≥ 40 years of age (50.4% vs. 36.7%)41, have a similar epidemiologic profile to other TV-infected women who are both HIV-infected36 and HIV-uninfected42, 43. Thus, our findings are likely generalizable to the majority of HIV-infected women in the U.S. though studies in Caucasian and Hispanic women are needed.

It is worth mentioning that while the 7 day dose was superior, the repeat infection rate in this arm was 8.5% at TOC and 11.0% at 3 months. Given the clinical and public health ramifications of untreated TV among HIV-infected women, a better understanding of the causes of treatment failure and more optimal treatment regimens for HIV-infected women beyond even the 7 day dose are needed. In addition to the repeat infection rates, the high TV prevalence identified through culture based screening for women eligible to participate in this study highlights the need for consistent, routine screening for TV among HIV-infected women.

In conclusion, the 7 day 500 mg BID dose of MTZ was more effective than the 2 gm single dose of MTZ for the treatment of TV among HIV-infected women. The recommendation of the MTZ 2 gm single dose as the standard treatment regimen for TV should be reconsidered for HIV-infected women based on the results of this trial. Future studies are needed to understand the host factors involved with treatment failure and to determine optimal treatment regimens for this population.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and staff from the participating clinics: HIV Outpatient Clinic and NOAIDS in New Orleans; Crossroads Clinic in Jackson; Thomas St. and Northwest Clinics in Houston. We also thank the staff from our study for their work in collecting and entering the data: Cheryl Sanders, Jessica Robinson, and Andrea Covington from New Orleans; Lucersia Nichols, Tina Barnes, Heather King, and Julia Miller from Jackson; Lena Williams, Amber Thomas, Dinna Lozano, and Yvette Peters from Houston; and for their work in the core laboratory: Cathy Cammarata, Judy Burnett and Denise Diodene. In addition, we thank the following biostatisticians from Tulane University for advising us: Lillian Yau and Janet Rice.

This study was supported by NIH grant # U19 AI061972.

Footnotes

Presented, in part, at the 2010 National STD Prevention Conference in Atlanta, GA from March 8-11, 2010 (Oral presentation B.3.e).

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01018095; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01018095.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.WHO Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2001 [PubMed]

- 2.Swygard H, Sena AC, Hobbs MM, Cohen MS. Trichomoniasis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management. Sex Transm Infect. 2004 Apr;80(2):91–95. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorvillo F, Kerndt P. Trichomonas vaginalis and amplification of HIV-1 transmission. Lancet. 1998 Jan 17;351(9097):213–214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorvillo F, Smith L, Kerndt P, Ash L. Trichomonas vaginalis, HIV, and African-Americans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001 Nov-Dec;7(6):927–932. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuomala RE, O’Driscoll PT, Bremer JW, et al. Cell-associated genital tract virus and vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in antiretroviral-experienced women. J Infect Dis. 2003 Feb 1;187(3):375–384. doi: 10.1086/367706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John GC, Nduati RW, Mbori-Ngacha DA, et al. Correlates of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission: association with maternal plasma HIV-1 RNA load, genital HIV-1 DNA shedding, and breast infections. J Infect Dis. 2001 Jan 15;183(2):206–212. doi: 10.1086/317918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce-Pratt R, Phillips DM. Studies of adhesion of lymphocytic cells: implications for sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Biology of Reproduction. 1993 Mar;48(3):431–445. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CC, McClelland RS, Reilly M, et al. The effect of treatment of vaginal infections on shedding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2001 Apr 1;183(7):1017–1022. doi: 10.1086/319287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kissinger P, Amedee A, Clark RA, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Jan;36(1):11–16. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318186decf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnus M, Clark R, Myers L, Farley T, Kissinger PJ. Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-Infected women: are immune status or protease inhibitor use associated with subsequent T. vaginalis positivity? Sex Transm Dis. 2003 Nov;30(11):839–843. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000086609.95617.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niccolai LM, Kopicko JJ, Kassie A, Petros H, Clark RA, Kissinger P. Incidence and predictors of reinfection with Trichomonas vaginalis in HIV-infected women. Sex Transm Dis. 2000 May;27(5):284–288. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissinger P, Secor WE, Leichliter JS, et al. Early repeated infections with Trichomonas vaginalis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Apr 1;46(7):994–999. doi: 10.1086/529149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kissinger P, Schmidt N, Mohammed H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment for Trichomonas vaginalis infection: a randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2006 Jul;33(7):445–450. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204511.84485.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Der Pol B, Williams JA, Orr DP, Batteiger BE, Fortenberry JD. Prevalence, incidence, natural history, and response to treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among adolescent women. J Infect Dis. 2005 Dec 15;192(12):2039–2044. doi: 10.1086/498217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S, Huengsberg M, Shahmanesh M. Treatment failure of vaginal trichomoniasis in clinical practice. Int J STD AIDS. 2005 Apr;16(4):284–286. doi: 10.1258/0956462053654258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2006. MMWR. 2006;55:RR-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tidwell BH, Lushbaugh WB, Laughlin MD, Cleary JD, Finley RW. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of single-dose intravaginal versus single-dose oral metronidazole in the treatment of trichomonal vaginitis. J Infect Dis. 1994 Jul;170(1):242–246. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spence MR, Harwell TS, Davies MC, Smith JL. The minimum single oral metronidazole dose for treating trichomoniasis: a randomized, blinded study. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 May;89(5 Pt 1):699–703. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)81437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonelli NM, Diehl SJ, Wright JW. A randomized trial of intravaginal nonoxynol 9 versus oral metronidazole in the treatment of vaginal trichomoniasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 May;182(5):1008–1010. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodcock KR. Treatment of trichomonal vaginitis with a single oral dose of metronidazole. Br J Vener Dis. 1972 Feb;48(1):65–68. doi: 10.1136/sti.48.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thin RN, Symonds MA, Booker R, Cook S, Langlet F. Double-blind comparison of a single dose and a five-day course of metronidazole in the treatment of trichomoniasis. Br J Vener Dis. 1979 Oct;55(5):354–356. doi: 10.1136/sti.55.5.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hager WD, Brown ST, Kraus SJ, Kleris GS, Perkins GJ, Henderson M. Metronidazole for vaginal trichomoniasis. Seven-day vs single-dose regimens. Jama. 1980 Sep 12;244(11):1219–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.duBouchet L, Spence MR, Rein MF, Danzig MR, McCormack WM. Multicenter comparison of clotrimazole vaginal tablets, oral metronidazole, and vaginal suppositories containing sulfanilamide, aminacrine hydrochloride, and allantoin in the treatment of symptomatic trichomoniasis. Sex Transm Dis. 1997 Mar;24(3):156–160. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleury FJ, Van Bergen WS, Prentice RL, Russell JG, Singleton JA, Standard JV. Single dose of two grams of metronidazole for Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977 Jun 1;128(3):320–323. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwebke JR, Morgan SC, Pinson GB. Validity of self-obtained vaginal specimens for diagnosis of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 Jun;35(6):1618–1619. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1618-1619.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatski M, Mena L, Levison J, Clark RA, Henderson H, Schmidt N, Rosenthal SL, Martin DH, Kissinger P. Patient-delivered partner treatment and Trichomonas vaginalis repeat infection among HIV-infected women. Sex Transm Dis. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d891fc. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caliendo AM, Jordan JA, Green AM, Ingersoll J, Diclemente RJ, Wingood GM. Real-time PCR improves detection of Trichomonas vaginalis infection compared with culture using self-collected vaginal swabs. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Sep;13(3):145–150. doi: 10.1080/10647440500068248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madico G, Quinn TC, Rompalo A, McKee KT, Jr, Gaydos CA. Diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection by PCR using vaginal swab samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1998 Nov;36(11):3205–3210. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3205-3210.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wendel KA, Erbelding EJ, Gaydos CA, Rompalo AM. Trichomonas vaginalis polymerase chain reaction compared with standard diagnostic and therapeutic protocols for detection and treatment of vaginal trichomoniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Sep 1;35(5):576–580. doi: 10.1086/342060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterman TA, Tian LH, Metcalf CA, et al. Persistent, undetected Trichomonas vaginalis infections? Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009 Jan 15;48(2):259–260. doi: 10.1086/595706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piantadosi S. Clinical trials : a methodologic perspective. 2nd ed Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, N.J.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunne RL, Dunn LA, Upcroft P, Donoghue PJ, Upcroft JA. Drug resistance in the sexually transmitted protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Res. 2003 Aug;13(4):239–249. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwebke JR, Barrientes FJ. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis isolates with resistance to metronidazole and tinidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(12):4209–4210. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00814-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez S, Fernandez-Verdugo A, Perez F, Vazquez F. Prevalence of 5-nitroimidazole-resistant trichomonas vaginalis in Oviedo, Spain. Sex Transm Dis. 2001 Feb;28(2):115–116. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid G, Narcisi E, Mosure D, Secor WE, Higgins J, Moreno H. Prevalence of metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis in a gynecology clinic. J Reprod Med. 2001 Jun;46(6):545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorvillo F, Kovacs A, Kerndt P, Stek A, Muderspach L, Sanchez-Keeland L. Risk factors for trichomoniasis among women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection at a public clinic in Los Angeles County, California: implications for HIV prevention. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998 Apr;58(4):495–500. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kissinger PJ, Dumestre J, Clark RA, et al. Vaginal swabs versus lavage for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis among HIV-positive women. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Apr;32(4):227–230. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151416.56717.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seth P, Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ. Exposure to alcohol problems and its association with sexual behaviour and biologically confirmed Trichomonas vaginalis among women living with HIV. Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Oct;84(5):390–392. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark RA, Theall KP, Amedee AM, Kissinger PJ. Frequent douching and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected women. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Dec;34(12):985–990. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31811ec7cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gatski M, Kissinger P. Observation of probable persistent, undetected Trichomonas vaginalis infections among HIV-positive women. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1086/653443. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and P . In: HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2007. Services USDoHaH, editor. Vol 19 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH, McQuillan G, Berman S, Markowitz L. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Nov 15;45(10):1319–1326. doi: 10.1086/522532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helms DJ, Mosure DJ, Metcalf CA, et al. Risk factors for prevalent and incident Trichomonas vaginalis among women attending three sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 May;35(5):484–488. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644b9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]