Abstract

Background

Interventions to treat unicameral bone cysts vary. Nonetheless, regardless of the intervention modality, the outcome is not certain. The purpose of this study was to determine if the distance between the growth plate and the cyst can be used to predict the outcome of the treatment.

Methods and materials

Retrospectively, we assessed the outcome of 39 interventions in nineteen children that were performed between 1994 and 2003. Seventeen different modalities of treatment were employed. There were three female and sixteen male patients. The average age was 8 years. Nine cysts were in the greater trochanter area, three were in the femoral capital area and seven were in the proximal humerus. According to the cyst's distance from the growth plate, at the intervention time, there were 18 cases within less than 2 cm and 21 cases of more than 2 cm.

Results

Complete healing was achieved in 10 children (employing seven different modalities). In nine of them, the cysts were more than 2 cm away from the growth plate. In one child, the cyst was within less than 2 cm of the growth plate, however, treatment here involved epiphyseodesis.

Discussion

This study confirmed that, regardless of intervention modality, complete healing was not achievable in those cysts that are within less than 2 cm of an active growth plate. Complete healing was possible in those cysts that are more than 2 cm away from the growth plate.

Conclusion

The 2-cm distance from the growth plate could be used as a predictor of treatment outcome of unicameral bone cysts.

Keywords: Unicameral bone cyst, Growth plate, Predictor, Outcome

Introduction

Despite being described as early as 1876 by Virchow [1], and regardless of the treatment modality, unicameral bone cysts are still difficult to treat successfully. Partial healing can be reversed with reactivation of the cyst sometimes several years after the initial treatment [2]. This difficulty was recognised in 1942 by Jaffe and Lichtenstein [3] who were the first to use the term solitary unicameral bone cyst and present a concise and clear description of the radiologic and pathologic features of these lesions and classify them into:

Active cyst: In which there is aberrant growth plate function. The cyst abuts the growth plate and it may be increasing in size with progressive thinning of the cortices. This is difficult to treat and partial response often reverses.

Latent cyst: There is normal growth plate function. The cyst is separated from the growth plate by normal bone. Treatment is more likely to succeed and partial healing is less likely reversed.

Nevertheless, the relation between the distance from the growth plate and the outcome of treatment was refuted by Neer et al. in 1966 [4]. However, as there are no further reports on this relation, we reinvestigated this in our study that aimed to determine whether the distance from the growth plate can be used to predict the outcome of unicameral bone cyst treatment.

Methods and patients

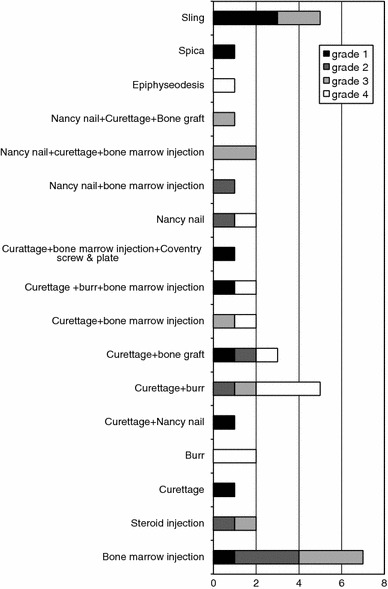

In this retrospective study we reviewed the outcome with nineteen children who had unicameral bone cysts who were treated between 1992 and 2003. The clinical and radiological notes of patients were reviewed. Gender, age, cyst location, history of previous fracture, early treatment, follow-up and subsequent treatment were all collected. Throughout the course of the study, 39 interventions were performed employing seventeen treatment modalities. These modalities included one or a combination of the following treatment options (Fig. 1):

Internal fixation using plate and screws or flexible intramedullary nailing.

Injection: steroid, bone marrow, water ± venting of cyst ± cystogram.

Curettage/dental burr.

Epiphyseodesis.

Grafting: osteoinductive, osteoconductive and as a mechanical support.

Fig. 1.

Healing grades according to the treatment modality

Radiological assessment included the cyst’s distance from the growth plate and any changes in this distance during the course of the study were documented. All radiographs were standardised according to radiology protocols. The distance was measured between the maximal proximal point of the cyst and the nearest point of the growth plate to the cyst. This was measured on the anteroposterior and lateral views and the smallest measurement was considered. A distance of more than 2 cm from the growth plate was used in this study to define latency. Healing was graded using the following system [5, 6].

Grade 1: cyst shows no response and still clearly visible.

Grade 2: cyst is visible with opacity of cavity and prominent septation (multilocular).

Grade 3: cortical thickening develops and cyst is partially visible.

Grade 4: there is complete healing with obliteration of the cyst.

There were three female and sixteen male patients. The average age at intervention was 8 years (range: 4–15). Nine cysts were in the greater trochanter area (distance measured from the trochanteric growth plate), three in the femoral capital area (distance measured from the capital growth plate) and seven in the proximal humerus. Follow-up was for at least 2 years for humeral cysts and 3 years for femoral cysts. However, the outcome of an intervention was considered a failure, if early complications were presented that dictated further intervention. None of the patients reached skeletal maturity during the course of the study, older children were followed up only until they achieved the minimum required follow-up without reaching maturity to avoid its confounding effect. Microsoft Office Excel 2007 was used to perform statistical tests and figures.

Results

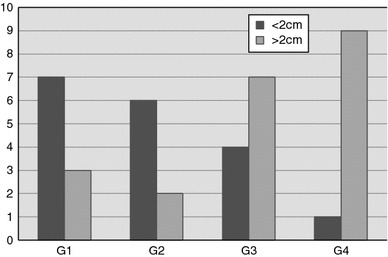

A summary of the final outcome according to cyst location is presented in Table 1. According to the cyst’s distance from the growth plate, at the time of intervention (N:39), there were 18 cases with a distance within less than 2 cm and 21 cases of more than 2 cm. The outcome according to treatment modality and to the distance from the growth plate is outlined in Figs. 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 1.

Final outcome according to cysts location

| Site | Not healed (Grades 1, 2 and 3) | Completely healed (Grade 4) | Average time to healing (months) | Average increase in distance from growth plate (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humerus | 4 | 3 | 9 | 14 |

| Capital | 1 | 2 | 24 | 15 |

| Trochanteric | 4 | 5 | 8 | 6 |

Fig. 2.

Healing grades according to the distance from the growth plate for 39 interventions

The association between outcome (grade 1, 2 and 3 vs. grade 4) and distance from the growth plate (more than 2 cm versus less than 2 cm) was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.019 Fisher’s Exact test, 2-tailed probability) with grade 4 more likely to be more than 2 cm from growth plate.

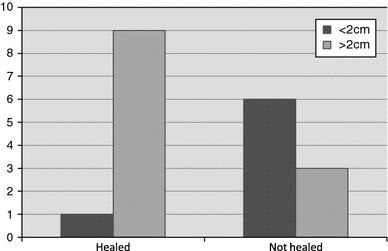

At the final follow-up, the cyst was within less than 2 cm from growth plate in 7 children and more than 2 cm away in 12 children. Complete healing (grade 4) was achieved in 10 children (Fig. 3), and in 9 of them the cyst was more than 2 cm away from the growth plate. In the tenth case, the cyst was within less than 2 cm from growth plate, however, treatment here involved epiphyseodesis (Fig. 4). In these 10 healed cases, seven different treatment modalities were employed.

Fig. 3.

Outcome of the 19 children according to distance from growth plate at final follow up

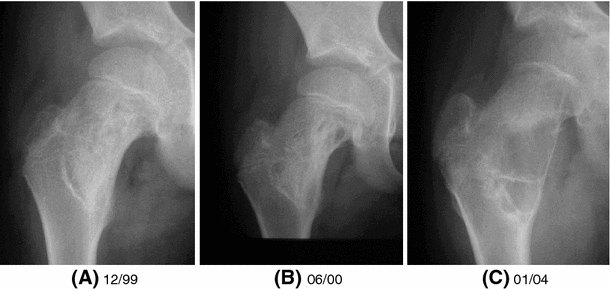

Fig. 4.

Grade 4 healing in a case within 2 cm from growth plate following Epiphyseodesis

In the other nine children, complete healing was not achieved and grades 1, 2 or 3 were the final outcomes. Of those, 6 cysts were less than 2 cm and 3 cysts were more than 2 cm from the growth plate. We paid special interest to the last 3 cases; one was in the proximal humerus and was initially within less than 2 cm of the growth plate, following nailing, it achieved grade 2 healing and seemed to move away from the growth plate. Subsequent follow-up showed reactivation and reversal to grade 1. Fortunately it was re-assessed and a CT scan confirmed that the cyst had in fact extended proximally and was still within less than 2 cm of growth plate (Fig. 5). The second case was in the femoral capital area and it achieved grade 4 healing following bone marrow injection. However, it subsequently reversed (Fig. 6) and although it seemed to be more than 2 cm from the growth plate, we strongly questioned whether there was still a cyst in the proximal medial corner of the femoral neck that abuts the growth plate (Fig. 6a–c). The third case showed grade 3 healing.

Fig. 5.

Cyst reactivation (a–c). CT scan showed that the cyst reaches the level of glenoid cavity and that it is within less than 2 cm from the growth plate (d)

Fig. 6.

Confounding case 3, Grade 4 healing and subsequent reactivation. Is there a cyst in the proximal medial corner of the femoral neck (C)

At commencement of the study, the distance from the growth plate was less than 2 cm in 11 cysts.

In seven cases, the distance continued to be less than 2 cm throughout the course of the study, only one case healed (epiphyseodesis case, Fig. 4).

In four cases, the distance increased to become more than 2 cm. Two of them completely healed and two failed to heal (confounding cases, Figs. 5 and 6).

Eight cases were more than 2 cm from the growth plate from the start, seven of them completely healed and one case showed grade 3 healing.

Discussion

UBCs form 3% of all primary tumours in children [7]. These lesions are not true neoplasms, they contain fluid, are multiloculated and usually expanding defects [7]. Approximately two-thirds occur in the metaphyseal region of the proximal femur and humerus [4]. Early theories suggested venous obstruction caused by a developmental anomaly as the cause of these cysts, [8] however, the aetiology remains uncertain and several treatment modalities are employed. For each modality, the outcome is uncertain in particular with regard to recurrence [9, 10]. Watchful waiting showed 14.5% healing [11]. Open curettage and bone grafting with autogenous or allograft bone has been associated with a recurrence risk ranging from 12 to 45% [12] and complications such as prolonged immobilisation, donor site morbidity and post operative pathological fracture. Intra-cystic injections of steroid and bone marrow showed a success rate of 42 and 23%, respectively [13].

As treatment success rates are limited and outcome is uncertain, predictors of outcome were sought. Initially, age was reported as a reliable predictor, with those children older than 10 years of age healing cysts at a higher rate than those under the age of 10 [14]. Nonetheless, in a more recent study, age was found not to affect the success rate of the outcome [15]. The cyst’s size was considered by Kaelin and MacEwen [16] who calculated the cyst’s index by relating its size to the squared diaphysis diameter. A cyst index of 3.38 for humeral cysts (N: 15) and 1.86 for femoral cysts (N: 11) were associated with treatment success. Higher indices were associated with failure. The accuracy of the measurements are doubtful, and there are no further reports on these measurements in the literature. The distance between the cyst and growth plate was another considered predictor, it has been used to define the conversion from an active cyst to latent one [3]. However, in a review of 175 cases, Neer et al. found that the distance effect to be insignificant and in this review, 0.5 cm was used as a distance from growth plate to determine latency. This apposition to the growth plate is too small, hence, it is too difficult to determine on plain radiographs and gives rise to a type 2 error. Often a lesion near a physis seems separated from the physis by a thin layer of cancellous bone, however, during surgery, the physis may be visualised at some points in the depth of the cyst [17]. Plain radiographs in such a case are misleading [17]. A 2 cm distance was used in our study to define latency to help reduce this error. Considering all 39 interventions, Fig. 4 demonstrates a clearly increasing tendency towards achieving better healing grades for cysts that are more than 2 cm away from growth plate. The tendency is in the opposite direction for cysts that are within 2 cm. This relation between outcome and distance from the growth plate was proven to be statistically significant (Fisher’s Exact test). At the final follow-up and irrespective of intervention (Fig. 2), all cysts that were within 2 cm of the growth plate did not achieve complete healing except for one case that underwent epiphyseodesis. Complete healing (grade 4) was possible for those cysts that are more than 2 cm away from growth plate.

It was noted that bone marrow injection was ineffective in achieving complete healing (Fig. 1). This injection is supposed to be an osteogenic stimulus; this strongly suggests that an inhibitory mechanism is preventing bone formation. On the other hand, mechanical disruption of the cyst such as using curettage and burr was found to be most effective (Fig. 1).

An active cyst under the influence of the growth plate is very difficult to heal; but osteogenic potential is already probably present. The inhibitory mechanism needs to be overcome to achieve permanent healing. We believe that those cysts that are close to the growth plate are communicating with it and most cysts that are more than 2 cm away do not communicate. Hence, we suggest that these cysts fall in one of the following two categories:

Simple bone cysts: These are the cysts that lost their physical communication with the growth plate. They are most of those cysts that are more than 2 cm away from growth plate. They have the potential to heal following an intervention (or even a fracture).

Developmental bone cysts: This class includes all cysts that are within 2 cm of the growth plate (the active cysts according to Jaffe and Lichtenstein [3]) and some of those that are of more than 2 cm away from it (the latent cysts according to Jaffe and Lichtenstein [3]). These are the cysts that are still communicating physically with the growth plate. They do not heal unless either the communication is disrupted or the growth plate closes operatively or at maturation.

This theory should stimulate further research in this field that may underline the basis of successful management of these cysts.

Using curettage and burr to disrupt the cyst’s membrane (and possibly cyst connection to growth plate) was the most effective treatment in our experience. However, the individual numbers for each treatment modality are too small for reliable conclusions on their effect and clearly there is some way to go before these ‘simple’ bone cysts can be treated reliably. Our management recommendations are:

Use a cystogram to define the cyst structure and its relation with the growth plate.

Avoid bone marrow injection as the sole intervention.

Use mechanical means to disrupt the cyst structure and lining.

Consider epiphyseodesis for femoral-capital cysts (>10 years old).

Repeat the treatment if there is no response within 6 months.

Follow-up 3 years for femur cysts and 2 years for humerus cysts.

Expect that a cyst remaining within 2 cm of the active growth plate to persist and reverse healing even if grade 4 healing is apparent.

Conclusion

In the presence of an active growth plate, complete healing was not achievable in those cysts that are within less than 2 cm from the growth plate. Complete healing was only possible in those cysts that are more 2 cm away from the growth plate.

The 2 cm distance from the growth plate could be used as a predictor of the treatment outcome of unicameral bone cysts.

References

- 1.Virchow RL. Uber die Bildung von Knochenzysten. Monats Akad Wissensch Berlin Phys Math Klasse. 1876;2:369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norman-Taylor FH, Hashemi-Nejad A, Gillingham BL, Stevens D, Cole WG. Risk of refracture through unicameral bone cysts of the proximal femur. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(2):249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L (1942) Solitary unicameral bone cyst, with emphasis on the roentgen picture, the pathologic appearance and pathogenesis. Arch Surg 44(6):1004–1025

- 4.Neer CS, Francis KC, Marcove RC, Terz J, Carbonara PN. Treatment of unicameral bone cyst: a follow up study of one hundred seventy five cases. J Bone Joint Surg [AM] 1966;48:731–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chigira M, Shimizu T, Arita S, Watanabe H, Heshiki A. Radiological evidence of healing of a simple bone cyst after hole drilling. Acta Orthop Trauma Surg. 1986;105:150–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00433932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashemi-Nejad A, Cole WG. Incomplete healing of simple bone cyst after injections. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1997;79:727–730. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B5.7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docquier PL, Delloye C. Treatment of simple bone cysts with aspiration and a single bone marrow injection. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(6):766–773. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. Simple bone cysts. Studies of cyst fluid in six cases with a theory of pathogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1960;42:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Sanctis N, Andreacchio A. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing is the best treatment of unicameral bone cysts of the long bones. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(4):520–525. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000217729.39288.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roposch A, Saraph V, Linhart WE. Flexible intramedullary nailing for the treatment of unicameral bone cyst in long bones. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(10):1447–1453. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garceau GJ, Gregory CF. Solitary unicameral bone cyst. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36(A:2):267–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dormans JP, Sankar WN, Moroz L, Erol B. Percutaneous intramedullary decompression, curettage and grafting with medical-garde calcium sulphate pellets for unicameral bone cysts in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(6):804–811. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000184647.03981.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright JG, Yandow S, Donaldson S. Marley L on behalf of the simple bone cyst trail group. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:722–730. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baig R, Eady JL. Unicameral (simple) bone cysts. South Med J. 2006;99(9):966–976. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000235498.40200.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho HS, Oh JH, Kim HS, Kang HG, Lee SH. Unicameral bone cysts: a comparison of injection of steroid and grafting with autologous bone marrow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(2):222–226. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaelin AJ, MacEwn GD. Unicameral bone cysts: natural history and the risk of fracture. Int Orthop. 1989;13(4):275–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00268511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanton RP, Abdel-Mota’al MM. Unicamral bone cyst. J Pediater Orthop. 1998;18:198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]