Abstract

Using energy and density guided Rosetta refinement to improve molecular replacement, we have determined the crystal structure of the protease (PR) encoded by xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV). Despite overall similarity of XMRV PR to other retropepsins, the topology of its dimer interface more closely resembles the monomeric, pepsin-like enzymes. Thus, XMRV PR may represent a distinct evolutionary branch of the family of aspartic proteases.

XMRV is a newly discovered human retrovirus and the first gammaretrovirus shown to be associated with human diseases. Its presence was detected in prostate cancer cells1, as well as in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome2. Although the identification of XMRV as the causal agent for these diseases is still controversial3, it is prudent to identify targets for designing drugs against this potential pathogen. Since XMRV is a retrovirus, inhibition of the three enzymes encoded in its genome (reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease) provides the most direct path to inactivation of the virus. It has already been shown that integrase inhibitor raltegravir is a potent inhibitor of XMRV4. Enzyme inhibition has been very successful in developing therapeutic agents active against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In particular, a large number of drugs targeting HIV-1 protease (PR) have been developed in the last 20 years5. Rapid success of these efforts depended very much on the availability of the structure of HIV-1 PR, as apoenzyme and in complexes with inhibitors6. Although all retroviral proteases that have been studied to date are structurally similar7, the fine differences in their structures allow for the development of the specific inhibitors. For example, whereas another potential drug target, HTLV-1 PR8, is similar to HIV-1 PR9, it is very poorly inhibited by most of the HIV-1 PR inhibitors. None of the clinical inhibitors of HIV-1 PR have EC50 values below 35 μM against XMRV in cell culture, i.e. 3–4 orders of magnitude higher than against HIV-14.

Although XMRV PR has not been previously isolated and/or expressed and characterized on molecular level, a closely related enzyme was isolated from Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) and its amino acid sequence was determined10. This information served as a guide in cloning XMRV PR (Supplementary Methods), and particularly in deciding on the location of the probable termini of the molecule. The expression construct contains 125 amino acids belonging to the enzyme, as well as a N-terminal His6 tag preceded by a methionine. The enzyme migrates as a dimer on a gel filtration column (not shown). Its activity was demonstrated by extensive autolysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a), as well as by cleavage of maltose binding protein (MBP) in the MBP-XMRV fusion protein (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Autolysis was inhibited by TL-3, a broad specificity retropepsin inhibitor (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1). This construct of XMRV PR was expressed, purified, crystallized, and diffraction data were collected to 1.97 Å resolution (Supplementary Methods).

Since XMRV PR contains only a single methionine near its C terminus (Met118), phasing of diffraction data by utilizing anomalous dispersion of selenomethionine did not appear to be feasible without introduction of additional Met residues. However, structural similarity of all known retroviral proteases7 suggested that molecular replacement (MR) should have been sufficient for solving the structure of XMRV PR. Extensive trials with models built on the basis of crystal structures of several retroviral proteases were performed, but no refinable solutions were found (Supplementary Methods). Finally, the structure of XMRV PR was solved through a novel application of the Rosetta refinement11 to several highest-scoring MR models. Such application of the Rosetta refinement (Supplementary Methods) led to sufficient improvement of these structures to enhance the MR signal and resulted in a model that could be further refined by standard means (Supplementary Table 1).

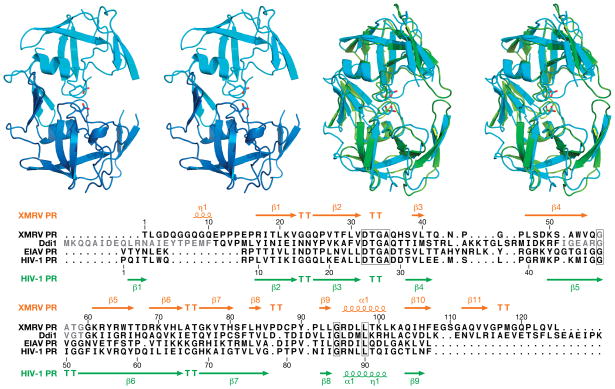

A molecule of XMRV PR is a homodimer (Fig. 1a), with the two-fold symmetry axis that does not coincide with the symmetry elements of the crystal. Its fold resembles in general the other retroviral proteases (Fig. 1b), although several large differences are present, especially at both termini of the molecule. Both the N and C termini are longer in XMRV PR than in most other retropepsins. The N terminus contains a helical insertion before strand β1 (Fig. 1c)). Instead of the interdigitated N and C termini (β1 and β9 strands, Fig. 1c) that create the dimer interfaces in all other structurally characterized retroviral proteases, the dimer interface of XMRV PR utilizes hairpins formed by strands β10 and β11, near the C termini of both monomers (Fig. 1c, Fig. 2a, and Supplementary Figs. 2a and 3). The flaps of each protomer (residues 48–66) are partially disordered at their tips, a situation common for the apoenzymes of retropepsins12. However, the ordered parts of the flaps appear to represent the open conformation seen in the apo form of HIV-1 PR13. The N-terminal fragment of XMRV PR is partially helical, with residues Gly6 through Glu11 disordered in monomer B, and is quite different from its counterparts in other retroviral enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

The structure of XMRV PR and a comparison with the fold of typical retroviral proteases. a) A dimer of XMRV PR in cartoon representation, with the two monomers colored cyan and blue and the catalytic aspartates shown as sticks. b) A superposition based on Cα coordinates of XMRV PR (cyan) and the apoenzyme of HIV-1 PR (green, PDB code 3hvp), shown in cartoon representation. c) Structure-based sequence alignment of the XMRV, HIV-1, and EIAV PRs, as well as Ddi1 RP. Secondary structure elements and residue numbers are marked above for XMRV PR and below for HIV-1 PR. Residues identical in all four enzymes are boxed. Panels a and b were prepared with PyMol18.

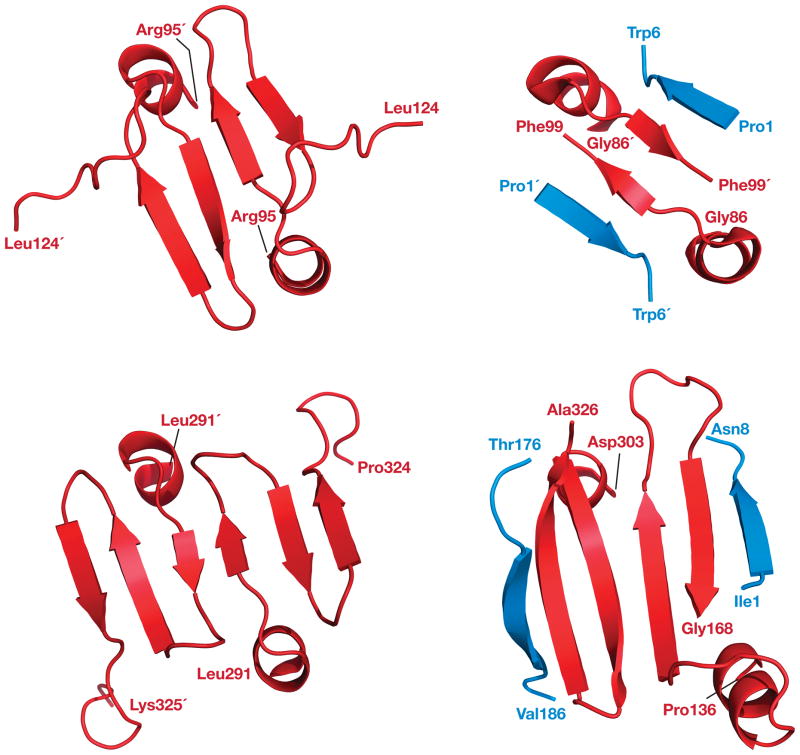

Figure 2.

Dimer interface regions in aspartic proteases. Strands belonging to the N-terminal regions of the molecules (or domains in pepsin) are blue, and the C-terminal regions are red. a) XMRV PR; b) HIV-1 PR; c) Ddi1 RP; d) pepsin.

Whereas the mode of dimerization of XMRV PR exhibits substantial differences from other retropepsins (Fig. 2b), it is much closer to that of the putative protease (RP) domain of the eukaryotic protein Ddi114. Crystal structure of the isolated RP domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ddi1 was solved and refined at 2.3 Å resolution (PDB code 2i1a14), revealing similarity in the overall structural fold to retropepsins. However, to our knowledge, no enzymatic activity of Ddi1 RP has been reported. The overall structural similarity (Supplementary Fig. 5) of XMRV PR and Ddi1 RP is reflected by the rmsds of 1.66 Å and 1.87 Å between the equivalent 85 Cα atoms in the monomers and 174 Cα atoms in the dimers of both proteins, respectively. By comparison, an analogous alignment of the monomer of XMRV PR with the apo form of HIV-1 PR (PDB code 3hvp13) yields rmsd of 2.18 Å for 85 Cα pairs, with the rmsd of 2.35 Å for the dimer.

As in the case of XMRV PR, the N and C termini of Ddi1 RP are substantially longer than in a majority of retropepsins. The dimer interface in Ddi1 RP is formed solely by the C-terminal part of the protomer (by three consecutive β strands (β7-β9), Fig. 1c) and does not include the N-terminus at all (Fig. 2c). A comparable situation is present in XMRV PR, with the exception that the interface utilizes fully only two β strands (β10-β11). Residues Gly119 and Gln120 make a turn after β11 and form hydrogen bonds with the O and N atoms of Gly116, thus extending the sheet, but the following segment of the C-terminal chain does not form any regular structure and points in a completely different direction (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2a).

As noted in the description of the structure of Ddi1 RP14, β strands that form the dimer interface in that protein are rotated by ~45° compared to their counterparts in HIV-1 PR and other retropepsins. Two of these strands in XMRV PR superimpose almost exactly on their counterparts in Ddi1 RP, retaining their angles, with only the residues at the turn between the interface strands following a slightly different path in the two proteins, despite their identical length (Supplementary Fig. 6). The axis of the dimer interface β sheet in XMRV PR is aligned roughly perpendicular to the long axis of the protease dimer. The direction of the interface strands and the lack of interdigitation resembles a situation seen in pepsin-like aspartic proteases, with the caveat that the dimerization interface in the latter enzymes is six-stranded (as in Ddi1 RP), as opposed to the four-stranded interface in XMRV PR (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Such a structure of the interface sheet results in a much smaller number of contacts with the opposite protomer in the dimer compared to other retropepsins, in which extensive intermolecular contacts are created by interdigitation of the C- and N-terminal β strands. However, XMRV PR used in this study is dimeric in solution as well as in crystals.

The two β strands that follow helix α1 in XMRV PR and Ddi1 RP and form the dimer interface are both topologically and structurally equivalent to the corresponding C-terminal loops of each domain of pepsin-like aspartic proteases (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2a), whereas the third strand is missing in XMRV PR. In this respect, XMRV PR seems to be closer to the putative common ancestor of monomeric and dimeric aspartic proteases15 than the other retroviral proteases, indicating divergence in their evolutionary paths.

A unique structural organization of N and C termini in XMRV PR leads to differences in the intersubunit interactions within the dimer interface compared to other retroviral enzymes. An important interaction stabilizing the dimers of retroviral proteases is created by an ion pair involving Arg8 of one protomer and Asp29′ of the other one (HIV-1 PR numbering) (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In contrast to all structurally characterized retropepsins, these two residues are not conserved in XMRV PR. A residue equivalent to Arg8 is Glu15 (Fig. 1c), but its side chain faces in an opposite direction, since the following Pro16 adopts a cis conformation. Although Pro16 in XMRV PR is conserved among retroviral proteases, the trans conformation of this residue in most of these enzymes leads to observed differences between topologies of the N-terminal strands. Gln36 in XMRV PR is an equivalent of Asp29 in HIV-1 PR and their respective side chains, in addition to varying the ionic state, also are oriented differently. Although simian foamy virus protease also lacks a corresponding ion pair, its structure was characterized by NMR only for a monomer16, and its dimer interface cannot be analyzed. These intersubunit ionic interactions are substituted by hydrophobic contacts in XMRV PR (Supplementary Fig. 2b), thus modifying the network of interactions within the dimer interface. It must be pointed out, however, that mutation R8Q in HIV-1 PR, which replaces the ion pair with polar interactions, leads to only small differences in the activity of the enzyme17, indicating that the presence of an ion pair may not be necessary to stabilize the dimer.

Similarly to other retropepsins crystallized in the absence of ligands, a water molecule bridges the two catalytic aspartates. The architecture of the active site in XMRV PR, in particular the hydrophobic lining of the binding site area, also resembles other retropepsins, suggesting that this enzyme might exhibit similar preferences in substrate recognition. As an example, loop Leu83-Leu92, equivalent to the so-called poly-proline loop in HIV-1 PR (residues Leu76-Ile84), adopts a conformation in XMRV PR that is very similar to that in other retroviral enzymes, as opposed to the one found in Ddi1 RP (Supplementary Fig. 7). As revealed by numerous structures of inhibitor complexes of retropepsins, residues of this loop are involved in extensive interactions with the ligands. Therefore, although only the structure of the apoenzyme form of XMRV PR is currently available, overall conservation of the structural features of retropepsins in the active site area allows prediction of the putative subsites for the residues of substrates and/or peptidic inhibitors. The residues predicted to form subsites S1-S4 in the monomer of XMRV PR are compared with their equivalents in HIV-1 and EIAV PRs in Supplementary Table 2. While the predominantly hydrophobic character of the binding sites is well preserved due to conservative nature of a majority of substitutions, the presence in XMRV PR of unique polar residues such as His37 in S2 and S4, Tyr90 in S1 and S3, Gln36 and Gln55 (presumably, since the fragment of the flap with this residue is disordered) in S3 and S5 provides clues for the design of specific inhibitors against XMRV PR. The other important difference observed in pocket S3 is due to the lack of conservation in XMRV PR of the previously mentioned Arg8 and Asp29 that form part of this pocket in the other retroviral enzymes. It is clear that further studies involving substrates and inhibitors of XMRV PR will be necessary in order to define specificity of this enzyme and to design more effective inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of beamline 22-ID of the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT), located at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the APS was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U. S. Government.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L. produced the protein and grew crystals; M.L. and Z.D. collected and processed crystallographic data; M.L., F.D.M, D.Z., A.G., J.L., and Z.D. performed calculations, structure refinement, and analysis; D.B. and A.W. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and participated in writing the manuscript.

Accession codes. Protein Data Bank: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the accession code 3nr6.

Reference List

- 1.Schlaberg R, Choe DJ, Brown KR, Thaker HM, Singh IR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16351–16356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906922106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Lombardi VC, et al. Science. 2009;326:585–589. doi: 10.1126/science.1179052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groom HC, et al. Retrovirology. 2010;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh IR, Gorzynski JE, Drobysheva D, Bassit L, Schinazi RF. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:249–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wlodawer A, Erickson JW. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:543–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn BM, Goodenow MM, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3006. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-4-reviews3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustchina A, Jaskolski M, Wlodawer A. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:463–464. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18322–18337. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshinaka Y, Katoh I, Copeland TD, Oroszlan S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1618–1622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMaio F, Tyka MD, Baker ML, Chiu W, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller M, Jaskólski M, Rao JKM, Leis J, Wlodawer A. Nature. 1989;337:576–579. doi: 10.1038/337576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wlodawer A, et al. Science. 1989;245:616–621. doi: 10.1126/science.2548279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirkis R, Gerst JE, Fass D. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang J, James MNG, Hsu IN, Jenkins JA, Blundell TL. Nature. 1978;271:618–621. doi: 10.1038/271618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartl MJ, Wohrl BM, Rosch P, Schweimer K. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis JM, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:868–875. doi: 10.1038/12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; San Carlos, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.