Abstract

Purpose

The study compared levels of depression among bullies, victims and bully-victims of traditional (physical, verbal and relational) and cyber bullying, and examined the association between depression and frequency of involvement in each form of bullying.

Methods

A U.S. nationally-representative sample of students in grades 6 to 10 (N = 7313) completed the bullying and depression items in the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) 2005 Survey.

Results

Depression was associated with each of four forms of bullying. Cyber victims reported higher depression than bullies or bully-victims, a finding not observed in other forms of bullying. For physical, verbal and relational bullies, victims and bully victims, the frequently-involved group reported significantly higher level of depression than the corresponding occasionally-involved group. For cyber bullying, differences were found only between occasional and frequent victims.

Conclusion

Findings indicate the importance of further study of cyber bullying as its association with depression is distinct from traditional forms of bullying.

Keywords: Cyber bullying, Traditional bullying, Depression

Bullying is a pervasive problem among children and adolescents, and may take various forms including physical (e.g., hitting), verbal (e.g., name-calling), relational (e.g., social isolation), or occurring in cyber space [1, 2]. Previous studies have consistently shown that depression is associated with exposure to bullying [3]. Bully-victims, a group of individuals who are both bullies and victims, are a distinct group at highest risk for psychosocial problems [4]. However, few studies have examined the association between depression and different forms of bullying [5]. In addition, because research on cyber bullying is still in its early stage, little is known about how level of depression differs in cyber bullies, victims, and bully-victims. The current study: (1) examines the association between depression and frequency of involvement in physical, verbal, relational and cyber forms of bullying and victimization; and (2) compares levels of depression among bullies, victims and bully-victims of each form.

METHODS

Sample and Procedure

A U.S. nationally-representative sample of adolescents in grade 6 through 10 was assessed in the 2005/2006 Health Behavior in School-aged Children study, using a three-stage stratified design [6]. Youth assent and parental consent were obtained as required by participating school districts. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Among the 7,508 adolescents who completed the anonymous paper survey, 195 (2.6%) were excluded due to missing information. The analytic sample (N = 7,313) consisted of 48.0% males, 42.3% Caucasian Americans, 18.5% African-Americans, and 26.4% Hispanic Americans. The mean age of the sample was 14.2 years (SD 1.42).

Measures

Socio-Demographic variables

Measures included gender, grade, race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and others) and family affluence [7].

Depression

Six items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [8] assessed depressive feelings and behaviors in the past 30 days : (1) very sad; (2) grouchy or irritable, or in a bad mood; (3) hopeless about the future; (4) felt like not eating or eating more than usual; (5) slept a lot more or a lot less than usual; and (6) had difficulty concentrating on their school work. Responses were coded one to five: never, seldom, sometimes, often, and always. This scale showed desirable reliability (Cronbach's alpha =.80).

Bullying/Victimization

Olweus’ revised bully/victim instrument [9] was used to measure physical (1 item, e.g., hitting), verbal (3 items, e.g., calling mean name) and relational bullying (2 items, i.e., social isolation and spreading false rumors), with added items measuring cyber bullying (2 items, i.e, using computers or using cell phones) [3]. For each item, two parallel questions asked frequency of bullying (bullying others) and victimization (being bullied) in the past couple of months at school. Following the recommendations of previous studies, the cutoff point was “two or three times a month” for frequent involvement and “only once or twice” for occasional involvement. Co-occurrence of bullying and victimization were examined, generating eight mutually exclusive groups: 1) non-involved, 2) occasional bullies, 3) occasional victims, 4) occasional bully-victims, 5) frequent bullies, 6) frequent victims, 7) frequent bully-victims, and 8) mixed frequency (individuals reporting both bullying and victimization but with different frequency levels).

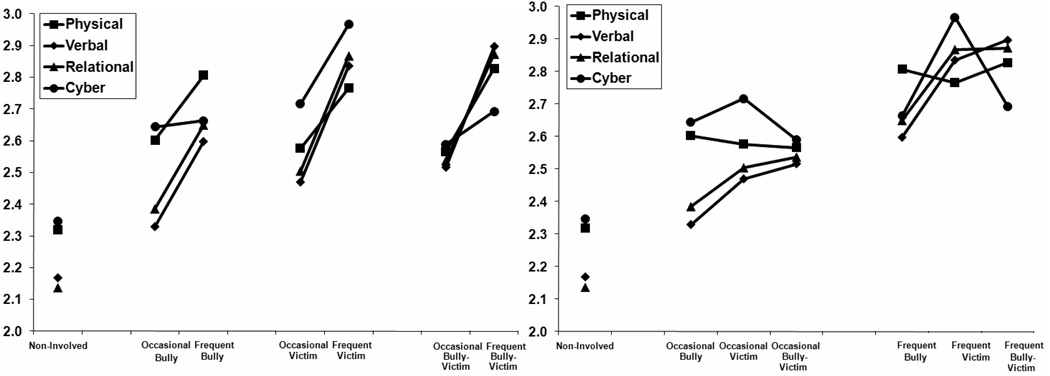

Statistical analysis

For each form of bullying, a regression analysis was conducted with depression as the outcome, the categorized measure of bullying and victimization as predictor, and socio-demographic variables as covariates. To test if the association between depression and bullying differed by gender, a gender by bullying interaction term was also included. Two sets of contrasts were tested in each regression model, with one comparing frequency levels and the other comparing bullies, victims, and bully-victims (see Figure 1). All analyses were conducted using STATA, version 9 [10] and an alpha of .05 as the significance level.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Means of Depression: Two Sets of Comparisons a

Note. a Means were adjusted for gender, grade, race/ethnicity, and family affluence. The first set compares occasionally involved and frequently involved within bullies, victims and bully-victims (the graph on the left). The second set compares bullies, victims and bully-victims within occasionally involved and frequently involved groups (the graph on the right). Based on results of previous studies described in the introduction, the following hypotheses were directional: 1) the frequently involved report higher level of depression than the occasionally involved; and 2) victims and bully-victims report higher level of depression than bullies. The Mixed group was not included in the mean contrasts, because frequency levels of bullying and victimization in this group were inconsistent.

RESULTS

Prevalence Rates of Bullying and Victimization

The percentages of those never, occasionally or frequently involved in bullying and victimization, as well as the percentages in the eight bullying/victimization groups are reported in Table 1. The prevalence of involvement in physical, verbal, relational and cyber bullying was 21.2%, 53.7%, 51.6% and 13.8%, respectively.

Table 1.

Frequencies and Percentagesa of Bulling or/and Victimization in Physical, Verbal, Relational and Cyber Forms (N = 7313)

| Physical | Verbal | Relational | Cyber | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Bullying | ||||

| Never | 6264 (86.5) | 4581 (62.5) | 5293 (72.4) | 6695 (91.5) |

| Occasional | 608 (8.0) | 1758 (24.4) | 1317 (18.2) | 298 (4.2) |

| Frequent | 441 (5.5) | 974 (13.2) | 703 (9.1) | 320 (4.3) |

| Victimization | ||||

| Never | 6286 (87.0) | 4521 (63.4) | 4177 (58.9) | 6574 (90.0) |

| Occasional | 546 (7.3) | 1457 (20.0) | 1786 (24.4) | 392 (5.6) |

| Frequent | 481 (5.8) | 1335 (16.7) | 1350 (16.7) | 347 (4.3) |

| Bullying/Victimization | ||||

| 1. Non-involved | 5675 (78.8) | 3321 (46.3) | 3434 (48.4) | 6299 (86.2) |

| 2. Occasional Bullies | 360 (4.8) | 827 (11.9) | 493 (6.9) | 147 (2.0) |

| 3. Occasional Victims | 342 (4.6) | 717 (9.5) | 1136 (15.1) | 248 (3.5) |

| 4. Occasional Bully-Victims | 162 (2.1) | 578 (8.1) | 510 (7.3) | 108 (1.6) |

| 5. Frequent Bullies | 251 (3.4) | 373 (5.2) | 250 (3.6) | 128 (1.9) |

| 6. Frequent Victims | 247 (3.1) | 543 (6.7) | 723 (9.1) | 148 (1.8) |

| 7. Frequent Bully-Victims | 148 (1.6) | 439 (5.5) | 313 (3.6) | 156 (1.9) |

| 8. Mixed b | 128 (1.6) | 515 (6.9) | 454 (5.9) | 79 (1.1) |

Note.

The percentages were calculated by adjusting for the sample design, including stratification (by census region and grade level), clustering (by school districts), and weighting (African-American and Hispanic adolescents were oversampled).

The Mixed group included individuals reporting both bullying and victimization but with different frequency levels. The purpose of including this group was to obtain a valid percentage for each of the above groups.

Results of Regression Analyses

Compared to the non-involved group, adolescents with any involvement in bullying or victimization reported higher level of depression across all four forms of bullying. The interaction of gender and involvement in bullying was not significant. The R2 of the four regression models were .115, .170, .189, and .107 for physical, verbal, relational, and cyber bullying, respectively.

Two sets of planned comparisons were conducted (Figure 1). For physical, verbal and relational bullying, the frequently-involved group reported significantly higher level of depression than the corresponding occasionally-involved group. For cyber bullying, differences were found only between occasional and frequent victims. For verbal and relational bullying, victims and bully-victims reported higher level of depression than bullies (both occasional and frequent groups). For cyber bullying, frequent victims reported significantly higher level of depression than frequent bullies. In addition, the difference between frequent cyber victims and frequent cyber bully-victims approached significance (p < .10).

Discussion

This study examined associations between depression and four forms of bullying: three traditional (physical, verbal, and relational) and a relatively new form (cyber). For traditional bullying, the associations between depression and frequency of involvement within bullies, victims, and bully-victims were consistent with previous studies [5]. For cyber bullying, on the other hand, these associations were not found for bullies or bully-victims. In addition, the comparisons of bullies, victims, and bully-victims showed different results across forms of bullying. Notably, cyber victims reported higher depression than bullies or bully-victims, which was not found in any other form of bullying. This may be explained by some distinct characteristics of cyber bullying [1]. For example, unlike traditional victims, cyber victims may experience an anonymous attacker who instantly disperses fabricated photos throughout a large social network; as such, cyber victims may be more likely to feel isolated, dehumanized or helpless at the time of the attack [1]. Findings indicate the importance of further study of cyber bullying as its association with depression is distinct from traditional forms of bullying.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School Bullying Among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021. 368-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellegrini AD. Bullies and victims in school: A review and call for research. J Appl Dev Psychol. 1998;19(2):165–176. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6):1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts C, Currie C, Samdal O, Currie D, Smith R, Maes L. Measuring the health and health behaviours of adolescents through cross-national survey research: Recent developments in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. J Public Health. 15(3):179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnohr CW, Kreiner S, Due EP, Currie C, Boyce W, Diderichsen F. Differential item functioning of a family affluence scale: Validation study on data from HBSC 2001/02. Soc Indic Res. 2008;89(1):79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlberg LL, Toal SB, Swahn M, Behrens C. Measuring violence-related attitudes, behaviors, and influences among youths: A compendium of assessment tools. Atlanta, GA: The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olweus D. Patent N-5015. Bergen, Norway: Research Center for Health Promotion (HIMIL), University of Bergen; The revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. 1996

- 10.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]