Abstract

P53 inactivation caused by aberrant expression of its major regulators (e.g., MDM2 and MDMX) contributes to the genesis of a large number of human cancers. Recent studies have demonstrated that restoration of p53 activity by counteracting p53 repressors is a promising anti-cancer strategy. Although agents (e.g., Nutlin-3a) that disrupt MDM2-p53 interaction can inhibit tumor growth, they are less effective in cancer cells that express high levels of MDMX. MDMX binds to p53 and can repress the tumor suppressor function of p53 through inhibiting its trans-activation activity and/or destabilizing the protein. Here we report the identification of a benzofuroxan derivative (7-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-nitro-1-oxido-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-1-ium, NSC207895) that could inhibit MDMX expression in cancer cells through a reporter-based drug screening. Treatments of MCF-7 cells with this small-molecule MDMX inhibitor activated p53, resulting in elevated expression of proapoptotic genes (e.g., PUMA, BAX, and PIG3). Importantly, this novel small-molecule p53 activator caused MCF-7 cells to undergo apoptosis, and acted additively with Nutlin-3a to activate p53 and decrease the viability of cancer cells. These results thus demonstrate that small molecules targeting MDMX expression would be of therapeutic benefits.

Keywords: MDMX, small-molecule inhibitor, p53, targeted therapy, apoptosis

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 is a gatekeeper of the genome, and maintains genetic stability upon oncogenic challenges by inducing cell cycle arrest, apoptosis or senescence (1, 2). Accordingly, p53 inactivation is a major driving force for tumorigenesis. In spite of wide-spread gene mutations, p53 is inactivated by aberrant expression of its regulatory proteins in many human cancers (1). Indeed, MDM2, a major p53 repressor, which potently inhibits p53 transcriptional activity (3) while targeting the tumor suppressor for ubiquitin-dependent degradation (4, 5), is overexpressed in more than 10% of human cancers (1). On the other hand, overexpression of the MDM2 homologue MDMX (also referred to as MDM4) occurs in 18–19% of breast, lung, and colon cancers (6), 50% of head and neck squamous carcinomas (7) as well as 65% of retinoblastomas (8). Although MDMX contains the RING domain, it lacks the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (9) and a prevailing view suggests that MDMX binds to p53 at its trans-activation domain thereby mainly repressing its transcriptional activity (1). However, emerging evidence suggests that MDMX can also regulate the stability of p53 through promoting MDM2-mediated degradation (10–14). Interestingly, overexpression of MDM2 and MDMX are mutually exclusive in cancer cells (6), suggesting that dysregulation of a major repressor is sufficient to inactivate p53 leading to tumor development. Because the TP53 gene often remains wild-type in MDM2- or MDMX-overexpressing cancers, it has long been conceived that targeting these p53 repressors could restore p53 activity thereby causing malignant cells to die or senesce (1, 15–17).

Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that small molecules disrupting the p53-MDM2 interaction can activate p53 leading to in vivo tumor regression (18, 19). A cis-imidazoline compound Nutlin-3a, for example, can dissociate the p53-MDM2 complex by binding to the latter protein and consequently inducing nuclear accumulation of p53 (18). As a result of p53 activation, Nutlin-3a sensitizes cancer cells to conventional cancer therapies (20–22) and inhibits growth of human tumor xenografts in nude mice (18). Notwithstanding these promising anti-cancer activities, Nutlin-3a can not induce apoptosis in cancer cells that express high levels of MDMX protein (e.g., MCF-7), presumably due to its inability to disrupt the p53-MDMX interaction (23–25). These studies thus indicate a need to develop agents targeting MDMX overexpression in cancer cells (26, 27). While MDMX siRNA (28)or a peptide simultaneously disrupting the interaction of p53 with MDM2 or MDMX (29) can inhibit tumor growth and sensitize MCF-7 cells to Nutlin-3a-induced apoptosis (24), small molecules exhibiting similar activities are more desirable for cancer therapy.

Given that MDMX overexpression in cancer is mainly caused by aberrant transcription (30), we applied a recent high-throughput drug screening (HTS) strategy (31) to search for small molecules that can inhibit MDMX transcription. We identified a small molecule that could down-regulate MDMX expression in various cancer cells. Most importantly, we found that this MDMX-targeting agent dramatically increased the p53 activity leading to expression of pro-apoptotic p53-target genes. This small molecule thus represents a new class of p53 activators that can restore the activity of the tumor suppressor leading to eradication of cancer cells.

Materials & Methods

Cell culture and transfections

MCF-7 and A549 cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, while LNCaP cells were routinely cultured in RPMI1640 medium. Breast cancer lines MDA-MB-175VII, ZR-75-1, ZR-75-30, MDA-MB-231, BT474, and BT549 were obtained from Dr. Ceshi Chen (Albany Medical College, Albany, NY), and cultured as recommended by the American Type Culture Collection. These cell lines have not been tested and authenticated by us. For transfections, cells were plated at 90–95% confluence, and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

Development of the luciferase reporter assay and drug screening

This was performed essentially as described previously (31, 32). Briefly, a fragment of the MDMX promoter (−1991 ~ +120, relative to the transcription start site) was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA derived from normal human fibroblasts WI-38 and cloned into the pCM-luc vector constructed previously (32). The plasmid containing the MDMX promoter and a FRT sequence was then co-transfected with the Flp-expressing pOG44 plasmid into HT1080/F55 cells (33), followed by selection for Hygromycin B-resistant clones. A random resistant clone was lysed for luciferase activity assay to confirm that the MDMX promoter was active and then expanded for drug screening. To determine the suitability of the recombinant cells for drug screening, cells plated in 96-well plates were treated with 1 µM actinomycin D for 16 h and lysed for luciferease activity assays. The relative promoter activity was then used to calculate the value of Z’-factor, which was defined in (34) and used to measure reproducibility of an assay in order to determine the suitability of the assay for high-throughput drug screening. For drug screening, recombinant cells plated in 96-well plates were treated with 5 µM of individual compounds from the NCI Diversity-Set library for 6 h and lysed for luciferase activity assays (31). Compounds decreasing the luciferase activity to 50% or more were further tested for their cytotoxicity using MTT assays as described (31) and subjected to a counter-screen using a CMV reporter to exclude general transcription inhibitors. The CMV promoter inserted into the same F55 genomic locus was prepared similarly as described above. A similar strategy was also employed to engineer the P1 or P2 promoter of the MDM2 gene (35) into the F55 locus.

Immunoblotting and cycloheximide chase assays

Immunoblotting was carried out as previously described (36). The following antibodies were used: DO-1 (for p53, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), p-S15-p53 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), MDMX (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), PARP (H-250, Santa Cruz), p21 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), MDM2 (SMP-14, Santa Cruz) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For cycloheximide chase assays, cells were treated with or without 100 µg/ml of cycloheximde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 h, and then lysed for immunoblotting as described (37).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed and subjected to real-time PCR assays essentially as described previously (33). The sequences of primers used for amplifying MDMX, p21, PUMA, BAX and PIG3 cDNA are available upon request.

shRNA knockdown

Knockdown was performed using a Lentivector-based shRNA system (pSIH-H1 shRNA Cloning and Lentivector Expression system, System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) as described previously (38). The targeted sequences for MDMX, p53 and MDM2 were 5’-GTG ATG ATA CCG ATG TAG A-3’, 5’-GAC TCC AGT GGT AAT CTA C-3’, and 5’-GGA ATT TAG ACA ACC TGA A-3’ based on publications (23, 39, 40), respectively. For negative controls, a luciferase-targeted sequence (5’-CTT ACG CTG AGT ACT TCG A-3’) was cloned into the Lentivector.

Flow cytometry and TUNEL staining

MCF-7 cells treated with DMSO, Nutlin-3a or the MDMX inhibitor were permeabilized with cold 70% ethanol overnight, and stained with a solution containing 50 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 µg/ml RNase A at 37°C for 20 min. The cells were then subjected to flow cytometry analysis as described previously (41). The FlowJo software was used to calculate percentages of cells in each cell cycle phase. For TUNEL staining, MCF-7 cells treated with the MDMX inhibitor for 2 days were fixed with 4% paraformadelhyde for 1h, and then subjected to dUTP labeling using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit TMR Red (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For quantitation, at least 300 cells were randomly chosen and the numbers of TUNEL-positive were counted.

Results

Identification of small molecules inhibitory for MDMX expression through drug screening

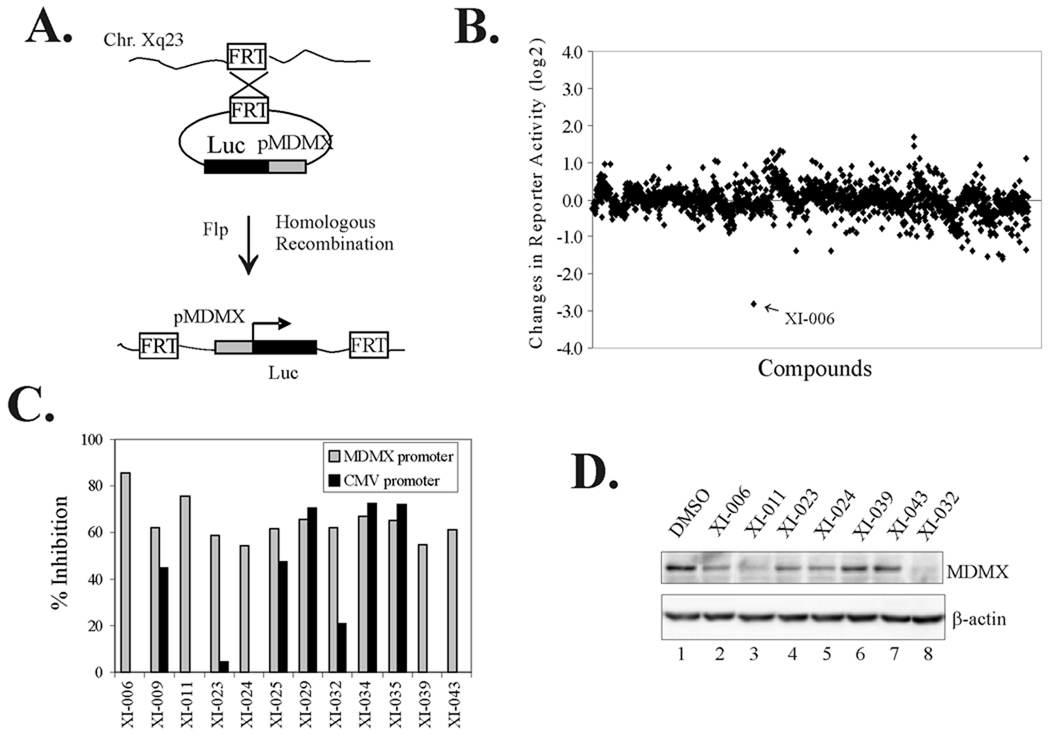

To search for small molecules that inhibit MDMX expression, we employed a recent FRT-based recombinant technology (31) to insert a firefly luciferase gene fused with a cloned MDMX promoter into a well-characterized genomic location in HT1080 cells (33), and generated recombinant cells carrying a luciferase reporter directed by the MDMX promoter (Fig 1A). As expected, actinomycin D, a general transcription inhibitor, decreased the reporter activity, and such effects were highly reproducible (Supplemental Fig S1), indicating that the recombinant cells were suitable for high-throughput drug screening (34). We therefore employed these cells to screen the NCI Diversity-Set chemical library (42) for small molecules that can diminish the MDMX promoter activity. 44 compounds (2.2%) were found to reduce the luciferase activity to at least 50% (log 2 scale < −1.0) (Fig 1B). Of the 44 compounds, 32 reduced the luciferase activity merely by decreasing cell viability (measured by MTT assays, data not shown) and thus were excluded from further investigation. We also excluded 5 compounds that decreased (>30%) the activity of a constitutively-active CMV promoter integrated into the same genomic location (Fig 1C) as they might inhibit gene transcription in general. The remaining 7 compounds were used to treat HT1080 cells for immunoblotting to validate their effects on MDMX expression. The results show that 3 compounds, XI-006 (NSC207895), XI-011 (NSC146109), and XI-032 (NSC25485) significantly inhibited MDMX expression (Fig 1D, lanes 2, 3, and 8). Of them, XI-006 (7-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-nitro-1-oxido-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-1-ium), a benzofuroxan derivative (Fig 2A), is less toxic according to the NCI toxicity database (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov), and thus was chosen for further investigation. We confirmed that XI-006 decreased the MDMX promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 2B), suggesting that this small molecule likely inhibited MDMX expression through repressing MDMX transcription.

Fig. 1. Discovery of small molecules inhibitory for MDMX expression through a promoter-based drug screening.

A, Schematic showing recombination between FRT fragments allowing for integration of a luciferase reporter gene driven by a MDMX promoter into a chromosomal location at Xq23 (33). B, Recombinant cells carrying the integrated MDMX promoter were plated into 96-well plates and treated with 5 µM of compounds derived from the NCI Diversity-Set chemical library for 6 h. Cells were then lysed for luciferase activity assays. The fold changes in the luciferase activity were converted into logarithm values (binary logarithm, i.e., log2) and plotted for each compound. C, Recombinant cells carrying the MDMX promoter or a CMV promoter were treated with the screening hits for 6 h and lysed for luciferase activity assays. D, HT1080 cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 24 h, and lysed for immunoblotting to measure MDMX expression levels.

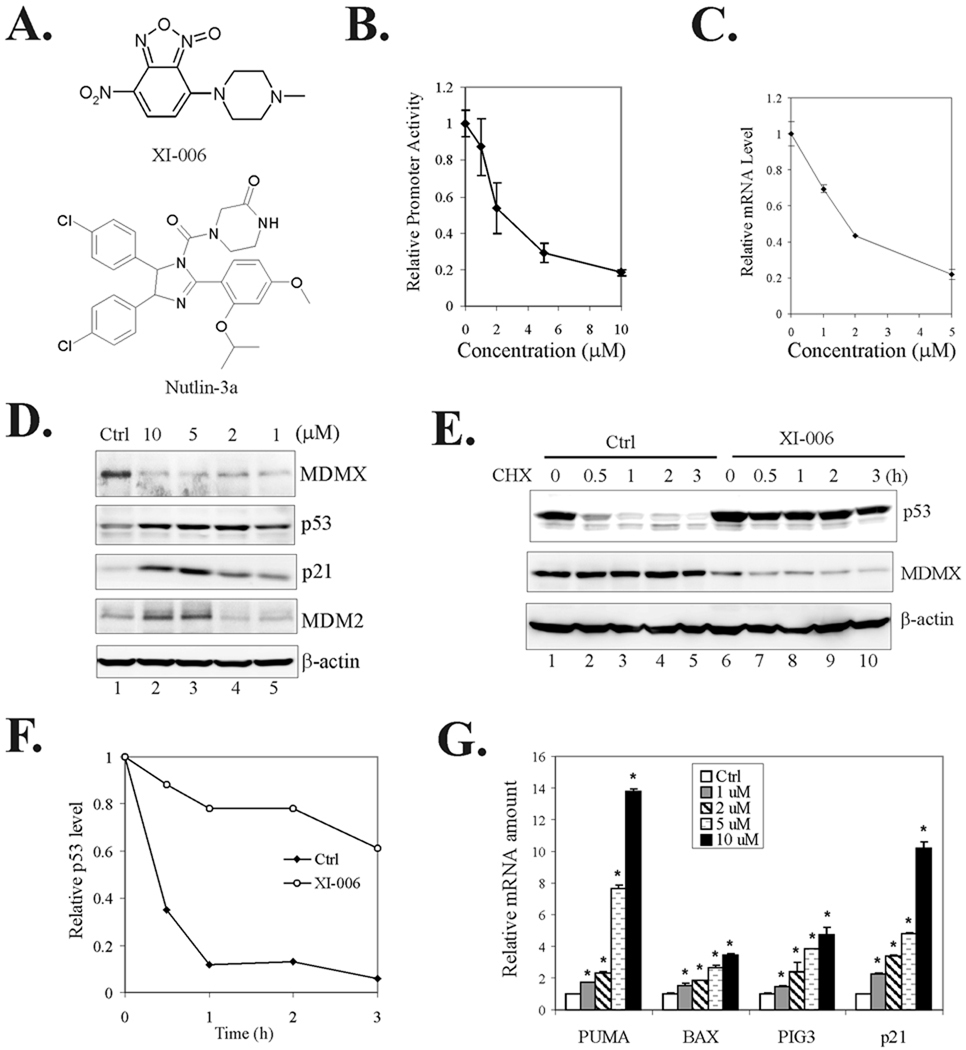

Fig. 2. A Small-molecule MDMX inhibitor activates p53 leading to activation of pro-apoptotic gene expression.

A, The chemical structures of XI-006 and Nutlin-3a. B, Recombinant cells carrying the MDMX promoter were treated with varying amounts of XI-006 for 6 h and lysed for luciferase activity assays. Data are depicted as average ± SD values of 3 determinations. C, MCF-7 cells were treated with XI-006 overnight and lysed for qRT-PCR assays to determine the MDMX mRNA levels. Data are depicted as average ± SD values of 3 determinations. D, MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO (Ctrl) or XI-006 for 16 h, and lysed for immunoblotting to measure expression levels of MDMX, p53, p21 and MDM2. E, After treatment with 5 µM of XI-006 for 16 h, MCF-7 cells were incubated with 100 µg/ml of cycloheximide. Cells were lysed at the indicated time and subjected to immunoblotting assays. F, Relative p53 levels in (E) was estimated by densitometry analysis. G, MCF-7 cells were treated as in (D). Total RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and cDNA subjected to qRT-PCR assays for measuring levels of PUMA, BAX, PIG3, and p21 mRNA. Data are depicted as average ± SD values of 3 determinations. *, p <0.05 versus the DMSO control (Student t-test).

Small-molecule MDMX inhibitor activates p53

Intrigued by the possibility that this MDMX-targeted agent could be used for cancer therapy, we treated MDMX-overexpressing MCF-7 cells (24) with the small molecule and determined whether p53 could be activated through inhibition of MDMX expression. Consistent with its capability to repress the MDMX promoter (Fig 2B), XI-006 decreased both the MDMX mRNA (Fig 2C) and protein levels (Fig 2D) in MCF-7 cells. Importantly, this novel MDMX inhibitor induced expression of p21, a well-characterized p53-target gene, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 2D), indicating that inhibition of MDMX expression by the small molecule indeed activated p53. Expression of MDM2, another p53 downstream gene, was also induced, despite to a less extent, by XI-006 (Fig 2D, lanes 2 and 3 vs. lane 1). Interestingly, XI-006 appeared to increase the p53 levels in MCF-7 cells (Fig 2D), suggesting that the small molecule could stabilize p53 as well. Indeed, the MDMX inhibitor extended the half life of p53 from 20–30 min to more than 3 h as revealed by cycloheximide chase assays (Fig 2E and 2F). These results are reminiscence of previous reports showing that MDMX downregulation by siRNA increases p53 levels (10, 29). Interestingly, in addition to MCF-7 cells, XI-006 also activated p53 and induced p21 and MDM2 expression in LNCaP prostate and A549 lung cancer cells (Supplemental Fig S2A and S2B).

One consequence of p53 activation is trans-activation of a group of genes (e.g., PUMA, BAX and PIG3) that link p53 to cell death signaling pathways leading to eradication of cancer cells. Indeed, results from qRT-PCR assays show that XI-006 increased the mRNA levels of PUMA, BAX and PIG3 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 2G). Although MDMX can regulate the functions of other genes(43, 44), the induction of pro-apoptotic gene expression by XI-006 in MCF-7 cells was most likely through activating p53 because these effects were largely impaired by shRNA-mediated p53 downregulation (Supplemental Fig S3). Therefore, the small-molecule MDMX inhibitor activated p53 leading to the expression of pro-apoptotic genes.

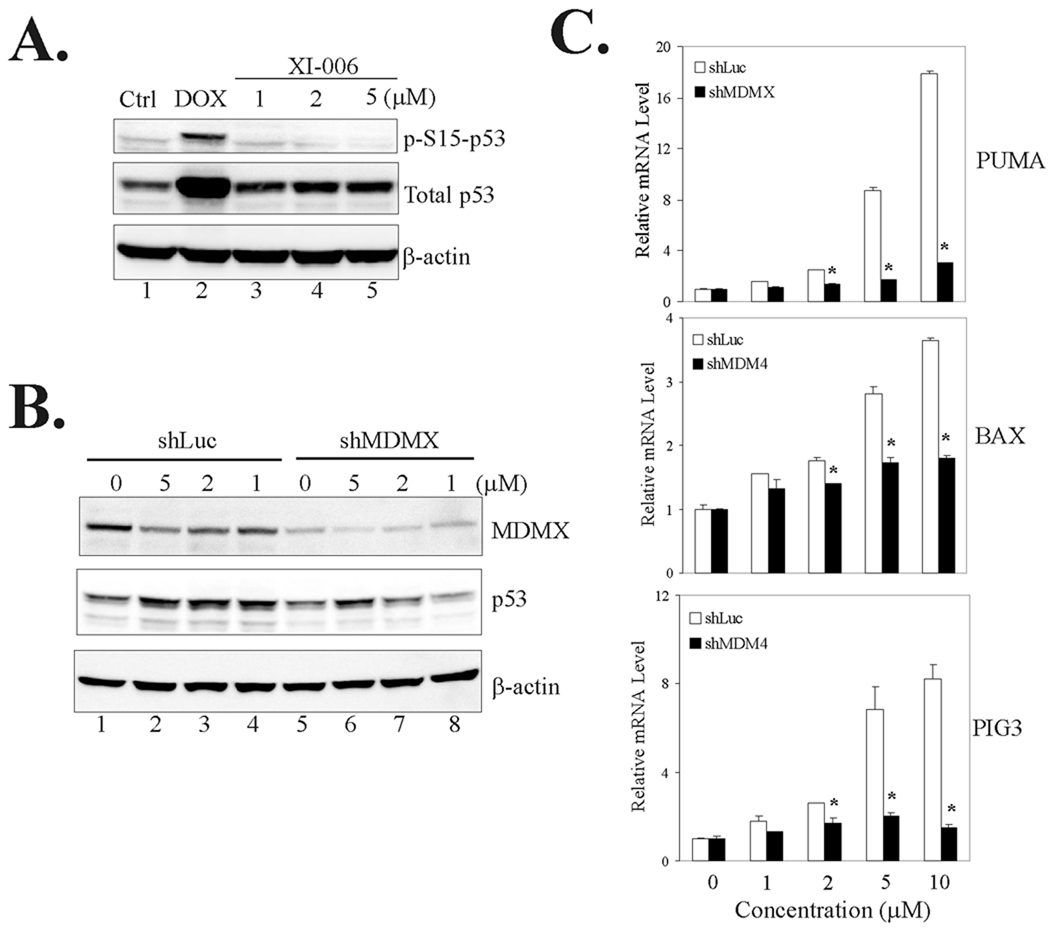

P53 activation by XI-006 is caused by inhibition of MDMX expression

Since DNA damage induced by small molecules can result in p53 activation, we sought to address an important question as to whether p53 activation by XI-006 was indeed a consequence of inhibition of MDMX expression. We thus treated MCF-7 cells with XI-006 and measured levels of serine 15-phophorylated p53 (p-S15-p53), a major cellular marker for DNA damage (45, 46), to determine whether the MDMX inhibitor could induce DNA damage at concentrations sufficient to activate p53 (Fig 2D and 2G). As expected, a known DNA-damaging agent doxorubicin (DOX) induced p53 phosphorylation (Fig 3A, lane 2). However, treatments with XI-006 failed to result in accumulation of phospho-p53 protein (Fig 3A, lanes 3–5) although the cellular p53 levels were still elevated after treatments (Fig 3A). These results thus argue against the notion that the MDMX inhibitor activates p53 through inducing DNA damage. To provide further evidence supporting that XI-006 activated p53 through inhibition of MDMX, we knocked down MDMX expression using Lentivector-based shRNA (shMDMX) and determined whether this treatment would compromise p53 activation by XI-006. Indeed, downregulation of MDMX expression largely impaired the increase of p53 levels (Fig 3B) and subsequent PUMA, BAX and PIG3 activation (Fig 3C), demonstrating that p53 activation by the MDMX-targeted agent was caused, at least in part, by inhibition of MDMX expression. Of note, knockdown of MDMX expression by the shRNA alone appeared insufficient to increase the cellular p53 levels and activate p53 (Fig 3B, lanes 5 vs. lanes 1) – an observation consistent with several (6, 23, 24) but in contrast to other reports (10, 29). The reason for this apparent discrepancy is unclear, but might be related to the complexity of the p53 regulatory network (17, 27)(see discussion).

Fig. 3. Activation of p53 by XI-006 is a consequence of inhibition of MDMX expression.

A. MCF-7 cells were treated with 0.5 µg/ml of doxorubicin (DOX) or XI-006 as indicated for 16 h and lysed to measure p53 phosphorylation levels. B, MCF-7 cells infected with Lentiviruses expressing shRNA specific to luciferase (shLuc) or MDMX (shMDMX) were treated with varying amounts of XI-006 for 24 h, and subjected to immunoblotting for p53 and MDMX expression. C, MCF-7 cells expressing shMDMX or shLuc were treated as in (B), and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis to measure the levels of the indicated mRNA. Data are depicted as the average ± SD values of 3 determinations. *, p <0.05 versus the corresponding shLuc cells (Student t-test).

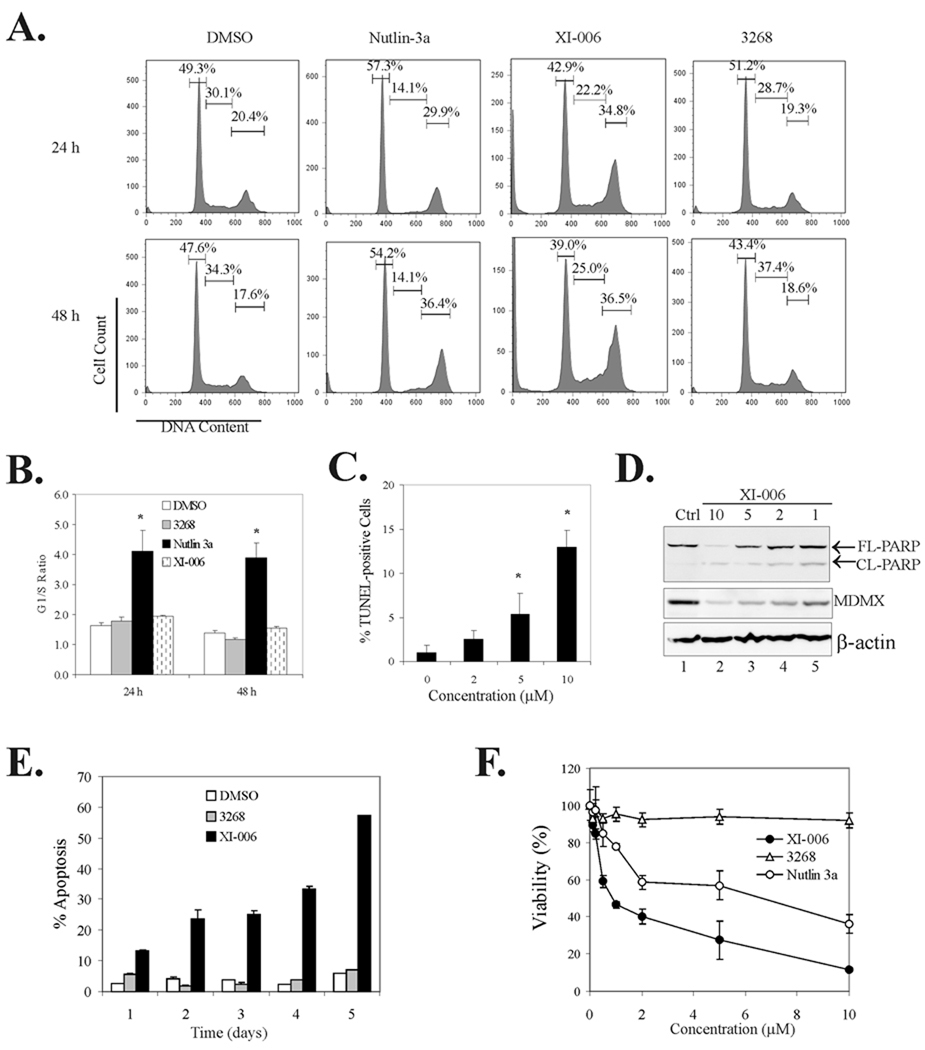

XI-006 induces apoptosis and inhibits cancer cell growth

Since the MDMX inhibitor induced pro-apoptotic gene expression, we performed flow cytometry assays to determine whether activation of p53 by XI-006 could induce apoptosis. Consistent with a previous report (24), the MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin-3a caused a significant reduction in the percentage of S-phase cells but failed to promote apoptosis in MCF-7 cells (Fig 4A and 4B). Conversely, treatment with XI-006 resulted in a significant increase in the numbers of subG0/G1 cells while G2 arrest was also apparent (Fig 4A), indicating that the MDMX inhibitor, unlike Nutlin-3a, could induce apoptosis. Indeed, TUNEL staining assays confirmed that XI-006 treatments resulted in increased number of apoptotic (i.e., TUNEL-positive) cells (Supplemental Fig S4 and Fig 4C). Moreover, the cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) - a biochemical marker for apoptosis - was largely induced by XI-006 (Fig 4D). These results thus support the notion that inhibition of MDMX expression by small molecules can promote apoptosis resulting in eradication of cancer cells. Indeed, while treatments of MCF-7 cells with 5 µM of XI-006 for 5 days resulted in more than 40% of cells died via apoptosis (Fig 4E), this MDMX-targeted agent dose-dependently reduced cell viability (Fig 4F). Moreover, XI-006 appeared more effective in decreasing cell viability than Nutlin-3a (Fig 4F, see the structure of Nutlin-3a in Fig 2A). Similar results were observed in A549 and LNCaP cells (Supplemental Fig S2C and S2D). Interestingly, compound 3268, an analogue of XI-006 (Supplemental Fig S4A), which was inactive in inhibiting MDMX expression and activating p53 (Supplemental Fig S4B), failed to induce apoptosis (Fig 4E), alter cell cycle progression (Fig 4B), or decrease cell viability (Fig 4F). It is important to note that XI-006 and compound 3268 have close predicted logP (logarithm of the oil-water partition coefficient) values around 1.5, arguing against the possibility that the lack of activity of the latter compound was likely due to poor cell entry.

Fig. 4. XI-006 induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells.

A & B, MCF-7 cells treated with 5 µM of Nutlin-3a, XI-006, or its analog compound 3268, or DMSO for 24 or 48 h were stained with PI and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Numbers inserted in graphs in (A) indicate percentages of cells at different stages of the cell cycle. The ratios of the numbers of G1 and S phase cells are shown in (B). C, MCF-7 cells treated with XI-006 for 48 h were subjected to TUNEL staining assays. At least 300 cells were randomly chosen and the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were counted. D, MCF-7 cells were treated with XI-006 for 2 days, and subjected to immunoblotting to detect cleaved (CL-PARP) and full-length (FL-PARP) PARP. E, MCF-7 cells were treated with 5 µM of XI-006, compound 3268, or DMSO for different days and subjected to flow cytometry to determine percentages of apoptotic cells (subG0/G1 cells). F, MCF-7 cells were treated with XI-006, compound 3268, or Nutlin-3a for 4 days. Cell viability was measured by MTT assays.

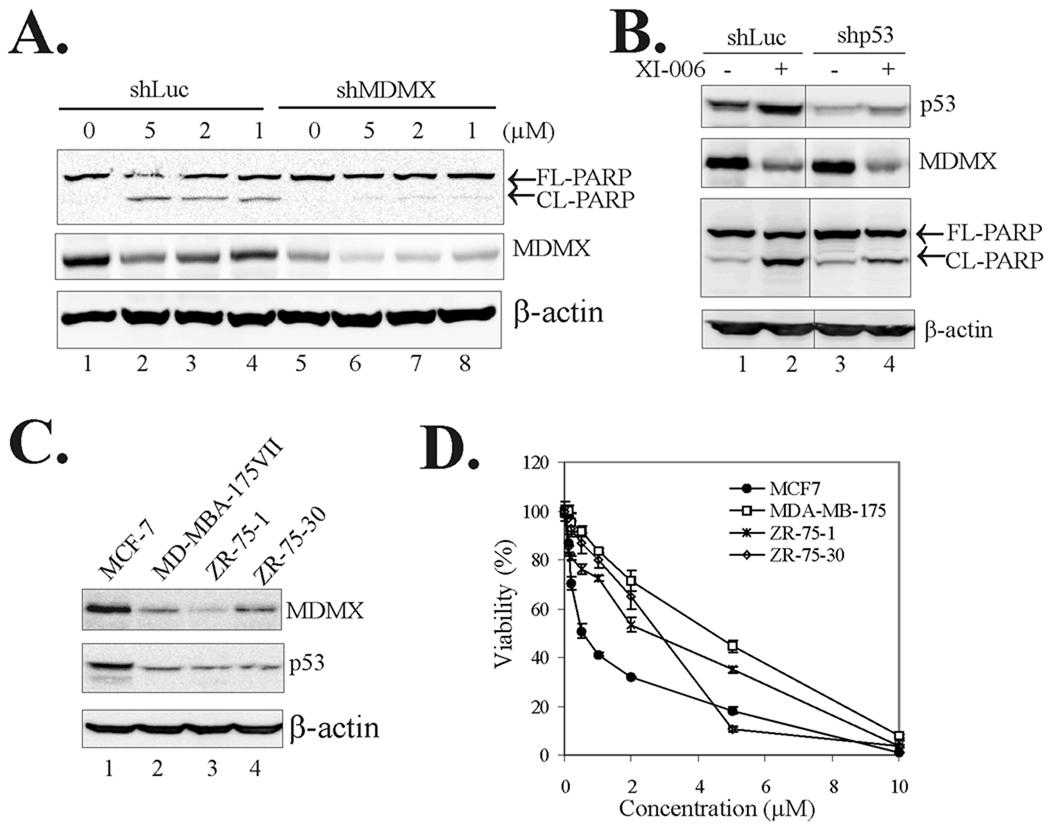

XI-006 induces apoptosis through inhibition of MDMX expression and activation of p53

To confirm that the apoptosis induced by the small molecule was indeed caused by inhibition of MDMX expression and activation of p53, we knocked down MDMX expression or p53 expression with shRNA in MCF-7 cells, and determined whether these treatments could impair the induction of PARP cleavage. Indeed, down-regulation of either MDMX expression (Fig 5A) or p53 expression (Fig 5B) abolished the induction of PARP cleavage by the small-molecule MDMX inhibitor. Interestingly, XI-006 appeared to be less effective in decreasing the viability of breast cancer cells that carry wild-type p53 but express low levels of MDMX (i.e., MDA-MB-175VII, ZR-75-1, ZR-75-30) (Fig 5C and 5D), consistent with the notion that XI-006 affects cancer cell growth mainly through regulating MDMX functions. On the other hand, although p53 activation is required for the induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 cells by XI-006 (Fig 5B), the MDMX inhibitor decreased the viability of several breast cancer cells that express mutant p53 (Supplemental Fig S6). These results are not unexpected given that MDMX can also bind to and regulate p63 and p73 (44, 47, 48), two other p53 family members which can alternatively trans-activate proapoptotic genes in the absence of functional p53 (49). It might also be possible that XI-006 targets pathway(s) that is less dependent on MDMX in these p53-mutated cells.

Fig. 5. XI-006 induces apoptosis through inhibition of MDMX expression and activation of p53.

A, MCF-7 cells infected with Lentiviruses expressing shLuc or shMDMX were treated with XI-006 for 2 days and lysed for immunoblotting assays as in Fig 4C. B, MCF-7 cells were infected with shLuc or shRNA specific to p53 (shp53), treated with 5 µM of XI-00 of XI-006 for 2 days, and lysed for immunoblotting assays. C, Breast cancer cell lines carrying wild-type p53 were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting assays. D, Indicated cells plated in 96-well plates were treated with XI-006 for 3 days and subjected to MTT assays for measuring cell viability.

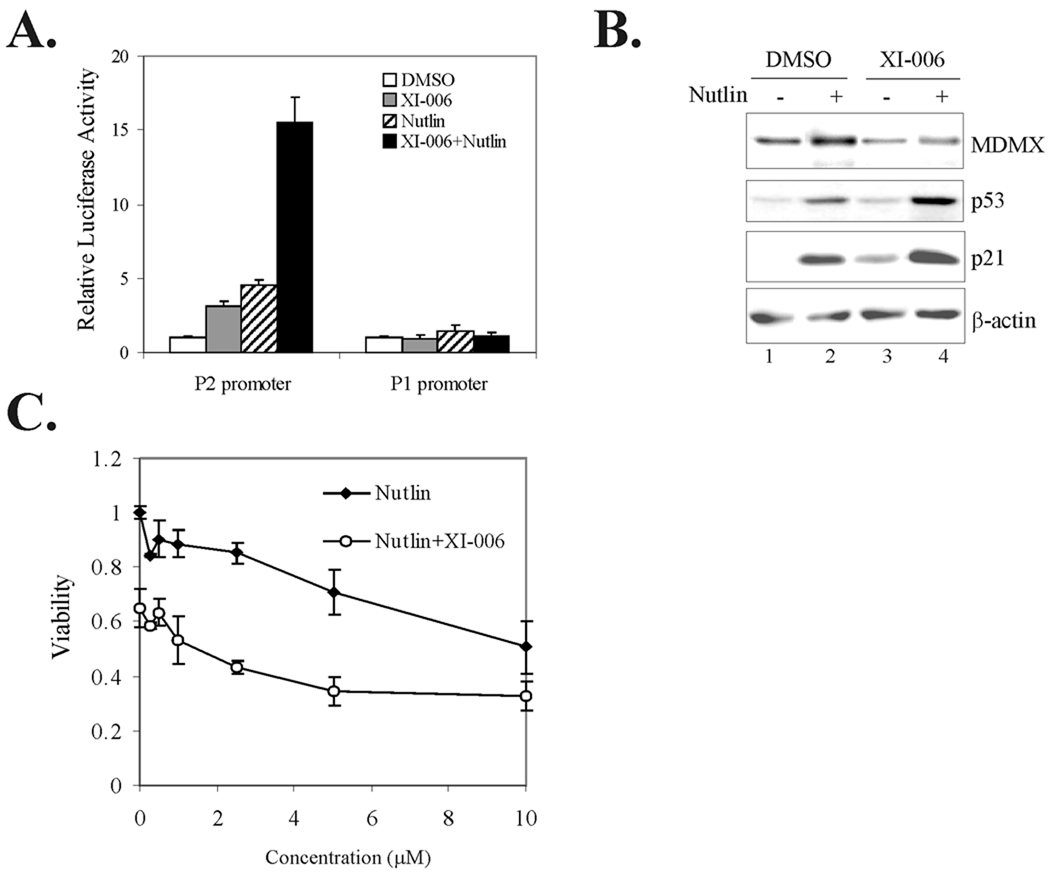

XI-006 enhances the effects of Nutlin-3a on cell viability

Nutlin-3a can disrupt the p53-MDM2 interaction but is less effective in dissociating MDMX from p53 (23–25). Since the binding of MDMX to p53 can repress p53 trans-activation activity, it is assumed that MDMX-targeted agents could cooperate with Nutlin-3a to activate p53 leading to cell death (23, 24). To explore this possibility, we applied the same strategy described in Fig 1A to develop a p53 reporter cell line in which a p53-responsive promoter (the P2 promoter of the MDM2 gene) (35) fused with a luciferase gene was integrated into the same genomic location as the MDMX promoter. For controlling reporter specificity, a cell line carrying a corresponding p53-nonresponsive promoter (the MDM2 P1 promoter) (35) in the same genomic locus was also developed. These cells were treated with XI-006 (2 µM) in combination with or without 5 µM of Nutlin-3a for 24 h and then lysed for luciferase activity assays. The results show that both the MDM2 and MDMX inhibitors increased the activity of the p53-responsive P2 promoter but not the P1 promoter, consistent with their p53-activating activities. Interestingly, the MDMX inhibitor XI-006 enhanced Nutlin-3a-induced p53 activation (Fig 6A). However, the effects were additive rather than synergistic (Fig 6A). To corroborate these results, we treated MCF-7 cells with these inhibitors and determined p53 activation by immunoblotting. Again, the MDMX inhibitor modestly increased the levels of p53 and p21 induced by Nutlin-3a (Fig 6B, lanes 4 vs. lane 2). Of note, consistent with a previous report (23), Nutlin-3a slightly increased the MDMX level, arguing against the notion that the MDM2 inhibitor can be used to down-regulate MDMX expression for cancer treatments. To further investigate the cooperation between the MDM4 inhibitors and Nutlin-3a, we treated cells with varying amounts of Nutlin-3a in combination with 2 µM of XI-006 for 4 days and measured cell viability using MTT assays. We found that XI-006 decreased cell survival in combination with low concentrations of Nutltin-3a in an additive manner (Fig 6C). Moreover, their effects on Nutlin-3a-induced decrease of cell viability were almost eliminated when the MDM2 inhibitor was at a high concentration (10 µM). Therefore, the small-molecule MDMX inhibitor could cooperate with the MDM2 inhibitor to activate p53 and decrease cell survival.

Fig. 6. XI-006 additively enhances p53 activation and anti-cancer effects of Nutlin-3a.

A, The p53-responsive P2 or -nonresponsive P1 promoter of the MDM2 gene was integrated into the same chromosomal location as in Fig 1A. Recombinant cells were treated with 5 µM of Nutlin-3a with or without 2 µM of XI-006 for 6 h, and lysed for luciferase activity assays. B, MCF-7 cells were treated with 5 µM of Nutlin-3a with or without 2 µM of XI-006 for 24 h, and lysed for immunoblotting to measure MDMX, p53 and p21 levels. C, MCF-7 cells were treated with varying amounts of Nutlin-3a with or without 2 µM of XI-006 for 4 days, and subjected to MTT assays to measure cell viability. Data are depicted as average ± SD values of 3 determinations.

Discussion

Given that MDMX is a major p53 repressor and its overexpression has been found in nearly 20% of human cancers (1, 27), it has been conceived that targeting MDMX expression could be an appealing strategy for the treatment of cancer. Through a promoter-based drug screening, we have identified a small molecule that can activate p53 by inhibiting MDMX expression and consequently induce the expression of pro-apoptotic genes leading to cancer cell death. This study thus provides the first evidence supporting the notion that small molecules targeting MDMX expression could be of therapeutic benefit to cancer patients. Interestingly, this small molecule was also identified in an earlier drug screening designed to search for small-molecule p53 activators (50), and thus its p53-activating activities has been independently validated. Therefore, XI-006 can serve as a lead compound for further development of a new class of therapeutic agents targeting MDMX expression in cancer.

One of the major thrusts of this study is to identify small molecules that can antagonize the repressive effects of MDMX on p53 trans-activation (27) in order to enhance the anti-cancer efficacies of MDM2 inhibitors (e.g., Nutlin-3a) in MDMX-overexpressing cancer cells (23–25). However, we found that the identified MDMX inhibitor additively, rather than synergistically, enhanced p53 activation induced by Nutlin-3a. Similar additive anti-cancer effects were also recently reported for a small-molecule inhibitor that directly binds to MDMX and disrupts the p53-MDMX interaction (51). Intriguingly, although both MDM2 and MDMX inhibitors can activate p53, the MDMX inhibitor differ from Nutlin-3a in that it could trans-activate pro-apoptotic genes in MCF-7 cells leading to cancer cell death, in line with the notion that MDMX-targeted agents could achieve better outcomes in treatments of MDMX-overexpressing cancers (23–25).

XI-006 is a benzofuroxan derivative and was shown in early reports that it can inhibit biosynthesis of nucleic acids and proteins (52) and exhibit cytotoxicity against murine leukemia cells (53). However, XI-006 unlikely down-regulated MDMX expression through inhibition of general protein/DNA synthesis as the levels of several other tested proteins including p21 and MDM2 were not decreased by the small molecule. Rather, current evidence is in line with the notion that the small molecule inhibited MDMX expression through targeting transcription of the MDMX gene. In this regard, XI-006 decreased not only the activity of the MDMX promoter (Fig 2B) but the MDMX mRNA level (Fig 2C). Moreover, although MDM2 can promote MDMX degradation (54), induction of MDM2 expression by XI-006 (Fig 2C) was rather a consequence than a cause of MDMX inhibition because the MDMX inhibitor retained its ability to decrease MDMX expression levels in cells where MDM2 or p53 expression was knocked down by shRNA (Supplemental Fig S7). Indeed, MDMX stability was not significantly altered by the two small molecules (Fig 2E). Interestingly, knockdown of MDM2 expression could slightly compromise the inhibition of MDMX expression caused by XI-006 treatments (Supplemental Fig S7B), suggesting that MDM2 induced by activated p53 could lead to a further decrease in the MDMX protein levels through promoting proteolysis of the latter protein. Further exploration of the mechanism(s) by which XI-006 inhibits MDMX transcription is difficult because the cis-/trans-regulatory elements contributing to MDMX transcriptional regulation are currently unknown.

An interesting finding in this study is that inhibition of MDMX expression by XI-006 not only enhanced the p53 transcriptional activity, but blocked p53 degradation. This finding argues against a prevailing model in which MDMX only plays a role in repression of p53 trans-activation (1, 27). However, increase of p53 stability by down-regulation of MDMX expression is not without precedent (6, 23, 24). Indeed, recent evidence strongly supports that MDMX is required for efficient ubiquitination and degradation of p53 mediated by MDM2 (12–14). MDMX can form a heterodimer with MDM2 via the RING domain (17), and such an interaction is essential for MDM2 to exert its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity towards p53 (12–14). Since we have shown that knockdown of MDMX expression by shRNA could abolish p53 activation induced by XI-006 (Fig 3B) and that the compound unlikely stabilizes p53 through inducing DNA damage (Fig 3A), it was unlikely that the observed p53-stabilizing effects (Fig 2B) were caused by an activity aside from inhibition of MDMX expression. Our results thus provide an additional support for the emerging role that MDMX plays in regulating p53 stability(12–14). If MDMX promotes p53 degradation, one question arises as to why MDMX shRNA failed to stabilize p53 (Fig 3B, lane 5 vs. lane 1). It is important to note that a siRNA sharing the same target sequence as the shRNA used in this study had a negligible effect on the p53 stability in MCF-7 but largely increased p53 levels in U2OS cells (23), suggesting that siRNA/shRNA, unlike the MDMX-targeted small molecule, might affect p53 stability in a cell-context dependent manner.

In summary, we have identified a small molecule that can inhibit MDMX expression. This agent represents a new class of small-molecule p53 activators that can induce apoptosis leading to elimination of malignant cells. This small-molecule MDMX inhibitor can also serve as a molecular probe for a better understanding of the p53-MDMX interplay and consequences of MDMX overexpression in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hua Lu, Jiandong Chen, Guillermina Lozano, J. P. Blaydes and Ceshi Chen for providing reagents and comments.

Grant Support: Supported by a Department of Defense grant PC061106 (W81XWH-07-1-0095) and a NIH grant R01CA139107 to CY.

Abbreviations list

- DOX

doxorubicin

- FRT

Flp recognition target

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- PI

propidium iodide

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary materials for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Therapeutics Online (http://mct. aacrjournals. org).

References

- 1.Toledo F, Wahl G. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vousden K, Prives C. Blinded by the light: The growing complexicty of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliner J, Pietenpol J, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubbutat M, Jones S, Vousden K. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danovi D, Meulmeester E, Pasini D, et al. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by Inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5835–5843. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5835-5843.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentin-Vega Y, Barboza J, Chau G, El-Naggar A, Lozano G. High levels of the p53 inhibitor MDM4 in head and neck squamous carcinomas. Human Pathol. 2007;38:1553–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurie N, Donovan S, Shih C-S, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shvarts A, Steegenga W, Riteco N, et al. MDMX: A novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996;15:5349–5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Kawai H, Nie L, et al. Mutual dependence of MDM2 and MDMX in their functional inactivtion of p53. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19251–19254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linares L, Hengstermann A, Ciechanover A, Muller S, Scheffner M. HdmX stimulates Hdm2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12009–12014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2030930100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai H, Lopez-Pajares V, Kim M, Wiederschain D, Yuan Z. RING domain-mediated interaction is a requirement for MDM2's E3 ligase activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6026–6030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poyurovsky M, Priest C, Kentsis A, et al. The Mdm2 RING domain C-terminus is required for supramolecular assembly and ubiquitin ligase activity. EMBO J. 2007;26:90–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uldrijan S, Pannekoek W-J, Vousden K. An essential function of the extreme C-terminus of MDM2 can be provided by MDMX. EMBO J. 2007;26:102–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chene P. Inhibiting the p53-MDM2 interaction: an important target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:102–109. doi: 10.1038/nrc991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vassilev L. p53 activation by small molecules: Application in oncology. J Med Chem. 2007;48:4491–4499. doi: 10.1021/jm058174k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wade M, Wahl G. Targeting Mdm2 and Mdmx in cancer therapy: Better living through medicinal chemistry? Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1–11. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vassilev L, Graves B, Carvajal D, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shangary S, Qin D, McEachern D, et al. Temporal activation of p53 by a specific MDM2 inhibitor is selectively toxic to tumors and leads to complete tumor growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3933–3938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao C, Shinohara E, Subhawong T, et al. Radiosensitization of lung cancer by nutlin, an inhibitor of murine double minute 2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:411–417. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbieri E, Mehta P, Chen Z, et al. MDM2 inhibition sensitizes neuroblastoma to chemotherapy-induced apoptotic cell death. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2385–2365. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coll-Mulet L, Lglesias-Serret D, Santidrian A, et al. MDM2 antagonists activate p53 and synergize with genotoxic drugs in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2006;107:4109–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu B, Gilkes D, Farooqi B, Sebti S, Chen J. MDMX overexpression prevents p53 activation by the MDM2 inhibitor nutlin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33030–33035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wade M, Ee T, Tang M, Stommel J, Wahl G. Hdmx modulates the outcome of p53 activation in human tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33036–33044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton J, Mayo L, Singhi A, Gudkov A, Stark G, Jackson M. Levels of HdmX expression dictate the sensitivity of normal and transformed cells to Nutlin-3. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3169–3176. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marine J, Dyer M, Jochemsen A. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J Cell Science. 2007;120:371–378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toledo F, Wahl G. MDM2 and MDM4: p53 regulators as targets in anticancer therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1476–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migliorini D, Lazzerini-Denchi E, Danovi D, et al. Mdm4 (Mdmx) regulates p53-induced growth arrest and neuronal cell death during early embroynic mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5527–5538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5527-5538.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu B, Gilkes D, Chen J. Efficient p53 activation and apoptosis by simultaneous disruption of binding to MDM2 and MDMX. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8810–8817. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilkes D, Pan Y, Coppola D, Yeatman T, Reuther G, Chen J. Regulation of MDMX expression by mitogenic signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1999–2010. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair R, Avila H, Ma X, et al. A novel high-throughput screening system identifies a small molecule repressive for matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:919–929. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan C, Wang H, Aggarwal B, Boyd D. A novel homologous recombination system to study 92 kDa type IV collagenase transcription demonstrates that the NF-κB motif drives the transition from a repressed to an activated state of gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:540–541. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0960fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan C, Boyd D. Histone H3 acetylation and H3 K4 methylation define distinct chromatin regions permissive for transgene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6357–6371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00311-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J-H, Chung T, Oldenburg K. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips A, Darley M, Blaydes J. GC-selective DNA-binding antibiotic, Mithramycin A, reveals multiple points of control in the regulation of Hdm2 protein synthesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:4183–4193. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan C, Wang H, Boyd D. KiSS-1 represses 92-kDa type IV collagenase expression by down-regulating NF-κB binding to the promoter as a consequence of IκBα-induced block of p65/p50 nuclear translocation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1164–1172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan C, Lu D, Hai T, Boyd D. Activating transcription factor 3, a stress sensor, activates p53 by blocking its ubiquitination. EMBO J. 2005;24:2425–2435. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Mo P, Ren S, Yan C. Activating transcription factor 3 activates p53 by preventing E6-associated protein from binding to E6. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13201–13210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brummelkamp T, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dornan D, Wertz I, Shimizu H, et al. The ubiquitin ligase COP1 is a critical negative regulator of p53. Nature. 2004;429:86–92. doi: 10.1038/nature02514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan C, Wang H, Boyd D. ATF3 represses 72-kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-2) expression by antagonizing p53-dependent trans-activation of the collagenase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10804–10812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shoemaker R, Scudiero D, Melillo G, et al. Application of high-throughput, molecular-targeted screening to anticancer drug discovery. Curr Topics Med Chem. 2002;2:229–246. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kadakia M, Brown T, McGorry M, Berberich S. MdmX inhibits Smad transactivation. Oncogene. 2002;21:8776–8785. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ongkeko W, Wang X, Siu W, et al. MDM2 and MDMX bind and stabilize the p53-related protein p73. Curr Biol. 1999;9:829–832. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shieh S, Ikeda M, Taya y, Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siliciano J, Canman C, Taya Y, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan M. DNA damage induces phosphorylation of the amino terminus of p53. Gene Dev. 2010;11:3471–3481. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadakia M, Slader C, Berberich S. Regulation of p63 function by Mdm2 and MdmX. DNA Cell Biol. 2010;20:321–330. doi: 10.1089/10445490152122433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Arooz T, Siu W, et al. MDM2 and MDMX can interact differently with ARF and members of the p53 family. FEBS Lett. 2001;490:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeYoung M, Ellisen L. p63 and p73 in human cancer: defining the network. Oncogene. 2007;26:5169–5183. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berkson R, Hollick J, Westwood N, Wood J, Lane D, Lain S. Pilot screening programme for small molecule activators of p53. In J Cancer. 2005;115:701–710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reed D, Shen Y, Shelat A, et al. Identification and characterization of the first small molecule inhibitor of MDMX. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10786–10796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kessei D, Belton J. Effects of 4-nitrobenzofurazans and their N-oxides on synthesis of protein and nucleic acid by murine leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 1975;35:3735–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belton J, Conalty M, O'Sullivan J. Anticancer agents XI: Anti-tumor activity of 4-amino-7-nitrobenzofuroxans and related compounds. Proc R Ir Acad. 1976;76B:133–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan Y, Chen J. MDM2 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of MDMX. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5113–5121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5113-5121.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.