Viral infection triggers a variety of signaling pathways to activate cellular antiviral responses. The host cells are equipped with pathogen recognition receptors, e.g., membrane-bound Toll like receptors (TLR), cytosolic RNA helicases (RIG-I and MDA-5) and Nod like receptors (NLR), which detect viral components that trigger intracellular transcriptional signaling pathways.1 Consequently, various steps of virus replication are inhibited by many induced antiviral proteins, such as interferon (IFN). Another effective antiviral mechanism used by the infected cells is to commit suicide by triggering premature apoptosis. Our recent study demonstrates that IFN-regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) can activate both antiviral pathways through its two independent actions as a transcription factor and a pro-apoptotic protein.2

We have recently shown that Paramyxoviruses can efficiently trigger cellular apoptosis via activation of RIG-I; this is independent of the IFN and NFκB signaling pathways, but IRF-3 plays an essential role.3 Interestingly, this process is regulated by the action of virus-activated PI3 kinase; inhibition of PI3 kinase activity markedly accelerates the apoptotic response.3 Investigation of the mechanism of the observed apoptotic role of IRF-3 revealed that, although it can induce the transcription of a few pro-apoptotic genes, its major action in this context is not dependent on its transcriptional activity. This conclusion is supported by the independent observation that overexpression of IPS-1, a component of the RIG-I signaling pathway, can induce apoptosis in cells expressing a transcriptionally defective mutant of IRF-3.4 Moreover, although both TLR3 and RIG-I signaling induces similar IRF-3-driven genes, TLR-3 signaling does not cause apoptosis.

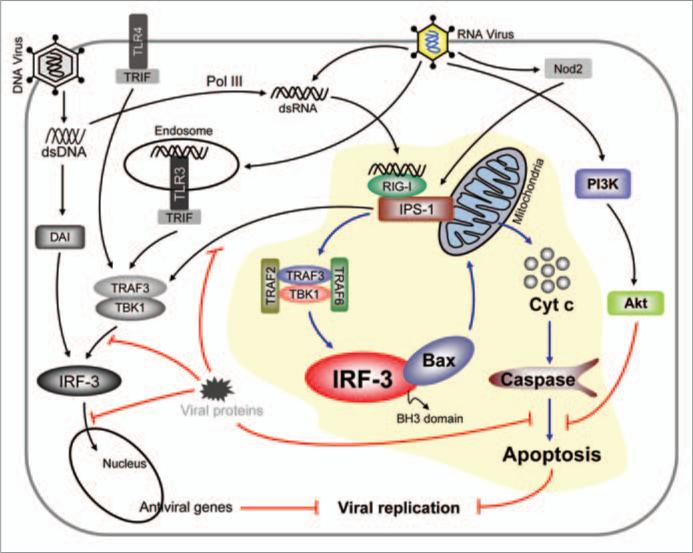

The novel IRF-3 mediated transcription-independent apoptotic pathway has been delineated in our recent study (Fig. 1).2 There are clear distinctions between the two IRF-3-activation pathways which make it competent as a transcription factor or an apoptotic factor; different signaling proteins are needed in the two pathways and different residues of IRF-3 are needed for the two activities. Similarly, translocation of the activated IRF-3 to two different sub-cellular compartments, mitochondria and nucleus, is needed for triggering the two responses. However, the mitochondrial translocation of IRF-3, by itself, is not sufficient for causing apoptosis; it needs interaction with the pro-apoptotic Bcl2-family protein Bax, which is mediated by the newly discovered BH3 domain of IRF-3. The interaction between IRF-3 and Bax is direct, causing activation of Bax through its conformational change and its co-translocation with IRF-3 to mitochondria. Interruption of any of these steps block apoptosis of the infected cell and promotes virus replication.

Figure 1.

Antiviral apoptotic pathway is mediated by IRF-3 and Bax. Many innate immune signaling pathways cause activation of IRF-3 as a transcription factor. Cytoplasmic dsRNA signals through RIG-I and IPS-1 to trigger both transcriptional and apoptotic antiviral pathways. For apoptosis, IRF-3 binds to Bax, activates it and translocates it to mitochondria, which cause cytochrome c release to the cytoplasm followed by caspase activation and apoptosis. Both pathways contribute to the antiviral state. Viruses employ many evasion strategies to block various steps of these pathways.

It is known that activation of IRF-3 as a transcription factor requires a conformational change caused by the phosphorylation of specific serine residues, but these residues are not needed for promoting apoptosis. However, the apoptotic activation may be achieved by the phosphorylation of other residues because the protein kinase TBK-1 is needed for both activation processes. It is conceivable that the apoptotic activation of IRF-3 causes a different conformational change that exposes the BH3 domain making it accessible to Bax. A similar mechanism operates for p53, which also can be activated either as a transcription factor or a pro-apoptotic factor that interacts with Bax.5 It is curious to note that TLR3, which, like RIG-I, recognizes viral dsRNA, does not activate IRF-3 to cause apoptosis. The observed need of TRAF2 and TRAF6 for the apoptotic activation and their engagement by RIG-I, but not TLR3, may be the underlying cause. It is also possible that the sub-cellular location of the signaling complex-associated IRF-3 makes the difference. In the case of RIG-I, presumably the complex assembles on the mitochondria-bound adaptor protein, IPS-1; whereas in the case of TLR3, the signaling complex assembles on the endosomal membrane to which the receptor is bound. It remains to be seen whether IRF-3-mediated apoptosis results from TLR4-signaling and dsDNA-signaling through DAI. Similar questions remain for the other cytoplasmic signaling pathways, triggered by Nod2 or dsDNA and Pol III, which converge on RIG-I (Fig. 1).

We have shown that at the cellular level the apoptotic antiviral response is critical; if this pathway is selectively blocked, the virus-infected cells not only survive but become persistently infected and turn into reservoirs of infectious viruses.3 The role of IRF-3-mediated apoptosis remains to be rigorously tested in mice, but the fact that IRF-3 deficient mice are more susceptible to viral pathogenesis than IFN-deficient mice suggests a major non-transcriptional role of IRF-3.6 This notion is supported by the essential role of Bax in mediating the apoptotic elimination of neuronal cells of mice infected with a variety of viruses. Another important determinant of viral homeostasis is the countermeasure taken by many viruses to evade host antiviral responses. It is well documented that many viruses can hide the infected cells from the recognition and elimination by different components of the immune system. There are also many known examples of viral proteins inhibiting the induction or the function of antiviral proteins.7 Similarly, viruses can also evade the cellular apoptotic response by a variety of strategies.8 Complex DNA viruses often encode anti-apoptotic proteins, whereas smaller RNA viruses activate cell's intrinsic anti-apoptotic pathways to evade or at least delay death of the infected cells. Paramyxoviruses achieve this goal by activating the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway. Sendai virus-infected cells survive for days; but when PI3 kinase is inhibited, they die within 8 hours after infection through the action of the IRF-3-driven apoptotic pathway. If the pathway is blocked, the infected cells survive indefinitely, even in the absence of PI3 kinase activity, and constantly produce progeny viruses (Fig. 1).3

Since this new pathway has just been discovered, many important questions remain to be addressed. The biochemical basis of activation of IRF-3, its mitochondrial translocation and its selective interaction with Bax remains to be elucidated. Currently it is not known how widely this pathway is activated by viruses of different families who use different lifestyles and elicit different cellular responses. The contribution of this pathway to viral pathogenesis in animals remains to be tested as well; in this context, it is particularly relevant that this pathway can regulate a switch from lytic infection to persistent infection.

References

- 1.O'Neill LA, et al. Curr Biol. 2010;20:328–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chattopadhyay S, et al. EMBO J. 2010;29:1762–73. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters K, et al. J Virol. 2008;82:3500–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu CY, et al. J Virol. 2010;84:2421–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02174-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chipuk JE, et al. Science. 2004;303:1010–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyotani K, et al. Virology. 2007;359:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conzelmann KK. J Virol. 2005;79:5241–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5241-5248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benedict CA, et al. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1013–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]