Abstract

Estrogen receptor (ER) signaling plays an important role in breast cancer progression and ER functions are influenced by coregulatory proteins. Proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein 1 (PELP1) is a nuclear receptor coregulator that plays an important role in ER signaling. Its expression is deregulated in hormonal cancers. We identified PELP1 is a novel cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) substrate. Using site-directed mutagenesis, and in vitro kinase assays, we identified Ser477 and Ser991 of PELP1 as CDK phosphorylation sites. Using the PELP1 S991-phospho-specific antibody, we show that PELP1 is hyper-phosphorylated during cell cycle progression. Model cells stably expressing the PELP1 mutant that lack CDK sites had defects in E2-mediated cell cycle progression and significantly affected PELP1-mediated oncogenic functions in vivo. Mechanistic studies showed that PELP1 modulates transcription factor E2F1 transactivation functions, that PELP1 is recruited to pRb/E2F target genes, and that PELP1 facilitates ER signaling cross talk with cell cycle machinery. We conclude that PELP1 is a novel substrate of interphase CDKs, and that its phosphorylation is important for the proper function of PELP1 in modulating hormone-driven cell cycle progression and also for optimal E2F transactivation function. Because the expression of both PELP1 and CDKs are deregulated in breast tumors, CDK-PELP1 interactions will have implications in breast cancer progression.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, coactivator, PELP1, oncogene, cyclin-dependent kinases

Introduction

Deregulation of the cell cycle is one of the hallmarks of cancer and is governed by the core cell cycle proteins like retinoblastoma (pRb) and cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) (1). Even though the role of CDKs in cell cycle progression is well established, defining the complete substrate repertoire of CDKs remains an enigma; many of their potential substrates yet to be identified. In spite of the known redundancy among CDKs, CDK4 and CDK2 co-operatively play an important role in the G1-S transition as attested by the mid-gestational embryonic lethality of the CDK2−/−/CDK4−/− double knockout mice and a delayed G1-S transition (2). Recent studies also found that CDK2 and CDK4 is essential for various oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis and that use of CDK2/CDK4 inhibitors may be a viable option for treatment of tumors with wild-type p53 (3). Collectively, these emerging studies suggest that phosphorylation of downstream effector proteins by these interphase CDKs play a crucial event in tumorigenesis.

Estradiol (E2) via the estrogen receptor (ER) promotes cell proliferation in a wide variety of tissues including mammary glands, and is implicated in breast cancer initiation and progression (4). Estrogen recruits non-cycling cells into the cell cycle and promotes G1 to S cell cycle phase progression. Induction of the early-response genes (such as c-myc and c-fos) is proposed as one mechanism of this process (5–7), whereas regulation of CDK2 and CDK4 activities is proposed as another (8–10). In addition, cyclin D1 was identified as a target of E2 action, and estrogen treatment was shown to up-regulate cyclin D1 levels (11). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying E2 regulation of G1/S phase transition is not completely understood.

Proline-, glutamic acid-, leucine-rich protein-1 (PELP1), a nuclear receptor coregulator plays an important role in estrogen receptor signaling (12). PELP1 is a recently discovered proto-oncogene (13) that exhibits aberrant expression in many hormone-related cancers (12) and is a prognostic indicator of shorter breast cancer specific survival and disease-free intervals when over-expressed (14). PELP1 appears to function as a scaffolding protein with no known enzymatic activity (12), and the mechanism by which PELP1 promotes oncogenesis remains elusive. We have previously shown that PELP1 over-expression promotes E2-mediated G1-S progression (15). Even though these findings suggest PELP1 may play a role in cell cycle progression, little is known about the molecular mechanism(s) responsible for its oncogenic function.

In this study, we identified PELP1 as a novel substrate of CDKs and found that CDK phosphorylation is important for the proper function of PELP1 in modulating hormone-driven cell cycle progression and also for optimal E2F transactivation function. Our findings revealed a novel mechanism by which CDKs utilize nuclear receptor co-regulators to assist cell cycle progression.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

Human breast cancer cells MCF7, ZR75, IMR-90, NIH3T3 and 293T cells were obtained from American-Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). All stable cell lines were generated through 500-μg/ml G418 (neomycin) selection. Estradiol was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The PELP1 antibody was from Bethyl lab (Montgomery, TX). Recombinant enzyme complexes, CDK4/CycD1, CDK2/CycE and CDK2/CycA and CDK antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-GFP antibody was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). PELP1 SMARTpool siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). PELP1-Phospho antibody was generated by Open Biosystems (Thermo-Fisher Scientifics; Huntsville, AL) against phospho-PELP1 Serine 991 (peptide sequence TLPPALPPPE(pS)PPKVQPEPEP). PELP1 220B2 antibody was generated by UTHSCSA core facility. The plasmids GST-PELP1 deletions (16), E2F-Luc (17) and GFP-PELP1 (16) were described previously. Expression vectors for p16-INK4A, CDK4, CDK2, and cyclin E were purchased from Addgene Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Expression vectors for E2F1 and DP1 were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). The PELP1 CDK site mutations were generated on either pGEX-GST-PELP1 deletions or GFP-PELP1 backbone by site-directed mutagenesis (Quick Change Mutagenesis Kit, Stratagene; La Jolla, CA). Yeast two hybrid screening was performed as described (18).

CDK Phosphorylation Assays

All in vitro kinase assays using CDK4 and CDK2 enzymes were performed using the kinase buffer comprising 60 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 3 mM MgCl2, 3 mM MnCl2, 3 μM Na-orthovanadate, 1.2 mM DTT, 10 μCi of [γ32-P] ATP and 100 μM cold ATP and the purified enzyme complex (100–200 ng/30 μL reaction). Bacterially purified GST-tagged full-length PELP1 and deletions were used as substrates for the in vitro CDK kinase assays. Each reaction was carried out for 30 min at 30°C and was stopped by addition of 10 μl of 4X SDS buffer.

Reporter gene assays

Reporter gene assays were performed by transient transfection using FuGENE6 method (Roche Indianapolis, IN) as described (17). Briefly, cells were transfected using 500 ng of E2F Luc reporter, 50 ng E2F, 50 ng DP1, 10 ng psv β-gal, with or without 200 ng of PELP1 wild-type (WT) or PELP1-CDK site mutant (MT) expression vectors. Cells were lysed in passive-lysis buffer 36–48 h after transfection, and the luciferase assay was performed using a luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison WI). Each transfection was carried out in 6-well plates in triplicate and normalized with either β-gal activity or the total protein concentration.

Real-time PCR and Cell Cycle Microarray

Cells were harvested with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was done using Superscript III RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was done using a Cepheid Smartcycler II (Sunnyvale, CA) with specific real-time PCR primers for the E2F target gene (Supplementary Table 1). Results were normalized to actin transcript levels and the difference in fold expression was calculated using delta-delta-CT method. Cellcycle micro array was purchased from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD) and analysis was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed as described previously (19). MCF7 or ZR75 cells expressing GFP-PELP1 WT or MT were cross-linked using formaldehyde, and the chromatin was subjected to immunoprecipitation using the indicated antibodies. Isotype-specific IgG was used as a control. DNA was re-suspended in 50 μl of TE buffer and used for PCR amplification using the specific primers (Supplementary Table 1).

Cell Cycle Analysis, Cell Synchronization and Cell Proliferation Assays

IMR-90 and NIH3T3 cells were synchronized to G0/G1 phase by serum deprivation for 3 days and released into the cell cycle by addition of 10% FBS-containing medium. MCF7, ZR75 and other derived model cell lines were synchronized to G0/G1 phase by serum starvation for 3 days in 0.5% dextran-coated charcoal-treated (DCC) serum containing medium and released into cell cycle by addition of 10−8 M E2. Double thymidine block was done to arrest model cells at late G1 phase (20). Flow cytometry was performed to analyze the cell cycle progression as described previously (15). Cell proliferation rate was measured by using a 96-well format with CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence, Confocal Microscopy, Immunohistochemistry Studies

Cellular localization of PELP1 WT or MT was determined by indirect immunofluorescence as described previously (19). Immunohistochemistry was performed using a method as described (21).

Tumorigenesis Assays

For tumorigenesis studies, model cells (5 × 106) were implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of 6- to 7-week-old female nude mice (n = 6 per group) as described (22). Each mice recieved one 60-day release E2 pellet containing 0.72 mg E2 (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) two days before implantation of cells, and tumors were allowed to grow for 6 weeks. Tumor volumes were measured with a caliper at weekly intervals. After 6 weeks, the mice were euthanized, and the tumors were removed, weighed and processed for IHC staining. Tumor volume was calculated using a modified ellipsoidal formula: tumor volume = 1/2(L × W2), where L is the longitudinal diameter and W is the transverse diameter (23, 24).

Results

PELP1 is a novel substrate of interphase CDKs

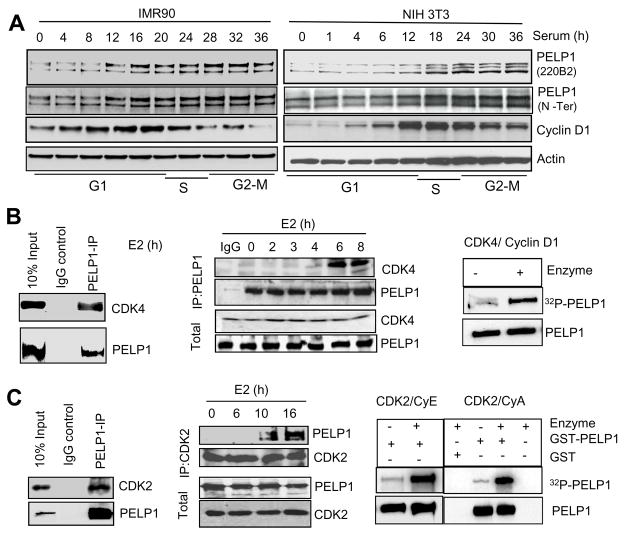

To examine the significance of PELP1 in cell cycle progression, we first analyzed the expression profile of PELP1 throughout the cell cycle using two normal cell lines, IMR-90 (human diploid fibroblast cell line) and NIH3T3 (murine fibroblast cell line) using an antibody (220B2) generated in our laboratory (Supplementary Fig. S1). Serum-starved fibroblast cells were synchronized to G1 phase and released into the cell cycle by addition of 10% serum, and the expression of PELP1 was analyzed on a 4–12% Bis-Tris gradient gel. In human fibroblast cells, two forms of PELP1 were detected: a slow-migrating form and a fast-migrating form (Fig. 1A, left panel). In murine fibroblast cells, two slower moving forms and one faster moving form were present during various phases of cell cycle (Fig. 1A, right panel). The PELP1 slower migrating bands were also detected by the PELP1 antibody that was previously generated in our lab (15) and was raised against N-terminal epitope aa 540–560 (Fig. 1A). Intriguingly, these slow-migrating bands were difficult to separate on non-gradient gels and escaped detection using existing commercial antibodies (data not shown). Shifted PELP1 bands were also seen in various cancer cell lines when stimulated with 10% serum (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Treatment of the total lysates with lambda phosphatase abolished the slower migrating forms (Supplementary Fig. S1C). These results suggested that PELP1 may be subjected to post-translational modification, which may be phosphorylation, during cell cycle progression.

Figure 1.

PELP1 is a novel substrate of interphase CDKs. A, Expression status of PELP1 in the cell cycle was analyzed in IMR-90 cells (left panel) and NIH3T3 cells (right panel). Cells synchronized at G0/G1 phase were released into cell cycle and lysates from different time intervals were used in Western blot analysis with the 220B2 PELP1 antibody. B, Total lysates from MCF7 cells grown in 10% serum were subjected to immunoprecipitation using the PELP1 antibody (left panel), and the CDK4 interaction was verified by Western blotting. T7-tagged PELP1 over-expressing MCF7 cells were treated with 10−8M estrogen for various periods of time, PELP1 was immunoprecipitated, and the CDK4 interaction was verified by Western blotting (middle panel). In vitro kinase assays for the CDK4/cyclinD complex using baculovirus-expressed GST-tagged full-length PELP1 as a substrate, and phosphorylation was measured by amount of 32P incorporation (right panel). C, Total lysates from MCF7 cells grown in 10% serum were subjected to immunoprecipitation using the PELP1 antibody and the CDK2 interaction was verified by Western analysis (left panel). MCF7 cells were treated with estradiol (E2) for various periods of time, and the PELP1 interaction with CDK2 was analyzed by using immunoprecipitation (middle panel). In vitro kinase assays using CDK2/CycE complex and CDK2/CycA2 complex (right panel) using full-length PELP1 as a substrate is depicted.

To identify potential kinases that phosphorylate PELP1 during cell cycle progression, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using mammary gland cDNA library with PELP1 as bait. One of the proteins identified using this screen was CDK4. We confirmed this interaction with purified plasmids in a yeast-based growth assay. The data indicate that the N-terminus (1–400 aa) of PELP1 functions as the CDK4-binding region (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Since PELP1 can participate in E2-mediated cell cycle progression, we used breast cancer model cells to further characterize the PELP1-CDK4 interaction. Using co-immunoprecipitation with PELP1 antibody, we found that PELP1 binds CDK4 in vivo (Fig. 1B, left panel) and E2 stimulation enhances the PELP1 interaction with CDK4 (Fig. 1B, middle panel). In a GST pull-down assay, GST-CDK4 efficiently interacted with the N-terminus of PELP1 and deletion analysis revealed that 200–350 aa in PELP1 serves as a docking site for CDK4 (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Using in vitro kinase assays with commercially procured CDK4/CyclinD1 and purified GST-tagged PELP1, we found that PELP1 can be efficiently phosphorylated by CDK4 in vitro (Fig. 1B, right panel). Studies have previously shown that E2-mediated cell cycle progression occurs through activation of interphase CDKs (both CDK4 and CDK2) (25). Since the slower moving forms of PELP1 persisted beyond G1/S phase (Fig. 1A) and because PELP1 has 11 consensus ‘Cy’ motifs- RXL, which are important for cyclin binding (26, 27), and four CDK2 phosphorylation motifs, we examined whether PELP1 interacts with CDK2 as well. Immunoprecipitation showed that PELP1 interacts with CDK2, (Fig. 1C, left panel) and that this PELP1-CDK2 interaction occurred at later stages (10–16 h of E2 stimulation) of cell cycle progression (Fig. 1C, middle panel). In vitro kinase assays using purified CDK2/cyclin E and CDK2/cyclin A complexes further showed that full-length PELP1 may also be a potential substrate of CDK2 (Fig. 1C, right panel). We further investigated whether CDKs phosphorylate PELP1 in vivo by co-transfecting PELP1 with or without CDK4/CycD1 and with natural or synthetic inhibitors of CDKs into 293T cells. Cells were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphoric acid and PELP1 phosphorylation was measured by using autoradiography after immunoprecipitation. Co-transfection of CDK4/CyclinD1 with PELP1 stimulated phosphorylation of PELP1 while cotransfection of the natural CDK4 inhibitor p16INK4 decreased CDK4/CycD1-mediated PELP1 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Both the CDK4 inhibitor Ryuvidine (28) and the CDK2 inhibitor Roscovitine (29) substantially reduced PELP1 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S3B,C); suggesting that PELP1 is a novel substrate of interphase CDKs.

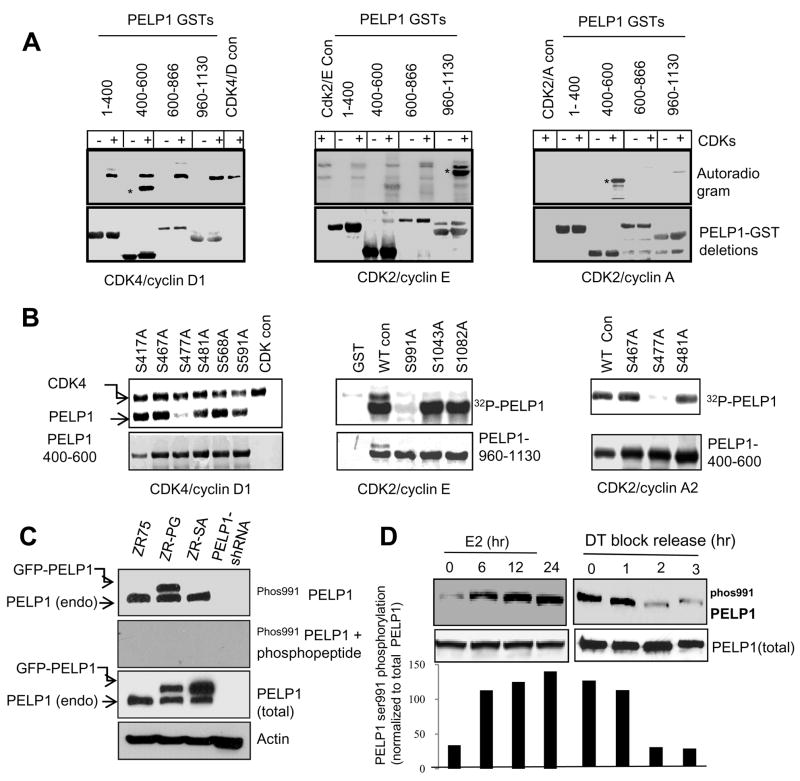

CDKs phosphorylate PELP1 at distinct sites

We next mapped the CDKs phosphorylation sites in PELP1 using a deletion and mutagenesis approach. PELP1 was expressed and purified as four small GST-fusion domains, which were used as substrates for the in vitro kinase assay. CDK4/CycD1 phosphorylated PELP1 domains containing 400–600 aa (Fig. 2A, left panel), while CDK2/CycE had a preference toward the PELP1 960–1130 aa fragment (Fig. 2A middle panel). Interestingly, CDK2/CycA2 uniquely phosphorylated PELP1 400–600 aa but had no activity in the PELP1 960–1130 fragment (Fig. 2A, right panel). We then mutated all the putative consensus CDK sites (S/T.P) and identified specific sites phosphorylated by each of three CDKs complexes. We found that CDK4/CycD1 preferentially phosphorylated Ser477, CDK2/CycE phosphorylated Ser991 and CDK2/CycA2 phosphorylated Ser477 (Fig. 2B). We also confirmed that these mutations in the context of full-length PELP1 significantly reduce CDK2/CycE- and CDK4/CycD1-mediated PELP1 phosphorylation when measured by using an in vivo orthophosphate labeling assay (Supplementary Fig. S3D).

Figure 2.

Identification of phosphorylation sites and generation of phosphospecific antibody. A, Bacterially expressed GST-PELP1 deletions were used as substrates for an in vitro kinase assay using CDK4/cycD1 (left panel), CDK2/cycE (middle panel) and CDK2/cycA2 (right panel), and PELP1 domains phosphorylated by each kinase complex was identified by using autoradiography. B, Identification of CDK phosphorylation sites using site-directed mutagenesis (Ser to Ala). Various single mutants in the region of interest were used along with respective wild-type PELP1 deletion fragments. Loss of 32P incorporation revealed the successful identification of phosphorylation sites. C, Western blot analysis of native, wild-type-tagged PELP1 and tagged phosphomutant PELP1 with the S991 phospho-PELP1 antibody in the presence or absence of the phospho peptide. D, MCF7 cells were either arrested and released by estradiol (E2) stimulation (left panel) or synchronized into the G1-S boundary by double thymidine block were released into cell cycle by addition of thymidine-free media (right panel), and phosphorylation status of PELP1 was analyzed by using the S991 phospho-antibody.

To further characterize the in vivo relevance of the identified sites, we made an attempt to generate rabbit polyclonal phospho-specific antibodies against each of phospho-S991 and phospho-S477 sites. We were successful only in obtaining S991-phospho-antibody, while we failed to generate S477-phospho-antibody because of the poor antigenicity of the S477 peptide. The antibody was specific to PELP1 Ser991 phosphorylation as its recognition was efficiently competed by phosphorylated peptide but not by unphosphorylated peptide (Fig. 2C, left panel). Further, it efficiently recognized phosphorylated endogenous and GFP-tagged PELP1, but was unable to detect the Ser991 to Ala PELP1 mutant (Fig. 2C, left panel). Lambda phosphatase-treated ZR75 lysates also abolished the ability of the phospho-S991 antibody to recognize phopshorylated PELP1 in these cells (Supplementary Fig. S4A). E2 stimulation substantially increased the level of serine phosphorylation that is recognized by the Ser991 antibody (Fig. 2D left panel) and down regulation of ER signaling by anti-estrogen ICI 182780 substantially decreased Ser991 phosphorylation of PELP1 (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Using double thymidine block and release of cells, we found that PELP1 Ser991 phosphorylation accumulated at the G1-S boundary and gradually decreased thereafter as the cells progressed into other phases of the cell cycle (Fig. 2D, right panel). PELP1 Ser991 antibody was able to recognize the shifted bands seen in normal IMR-90 cells in gradient gels, when synchronized to G1 phase and released them into the cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. S4D). Overall these results demonstrate that interphase CDKs can phosphorylate PELP1 at Ser991 in vivo.

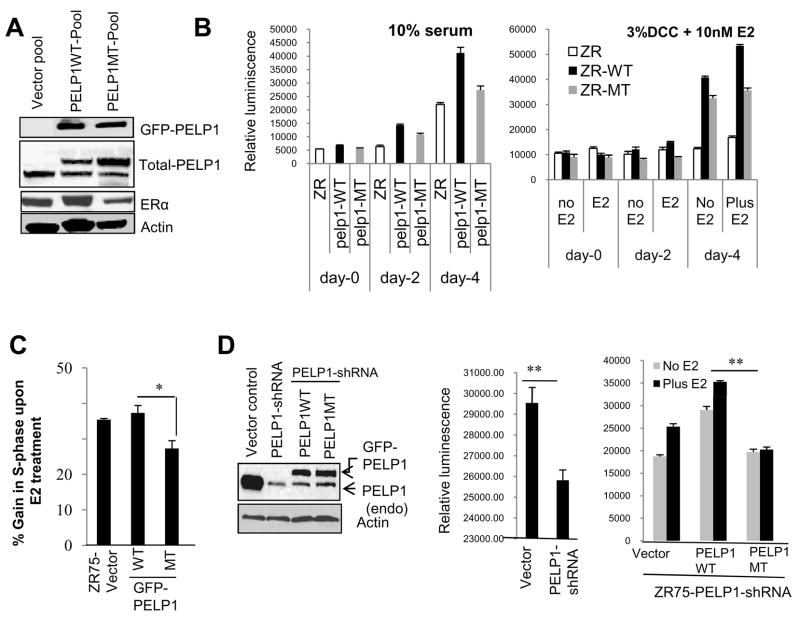

Mutations in CDK2 phosphorylation sites affect PELP1 functions

Since previous studies showed that PELP1 augments G1-S cell cycle phase progression, we investigated the significance of CDK phosphorylation of PELP1 in cell cycle progression. We constructed an N-terminal GFP-tagged PELP1 mutant that lacked these two CDK sites. ZR75 cells stably expressing PELP1-WT and PELP1-MT (pooled clones) were generated. Compared to other ER+ve breast cancer cells such as MCF7, ZR75 cells express low endogenous PELP1, therefore represent good model to study the effect of mutations by overexpression. In general, these stable clones express 3- to 4-fold more PELP1-MT than endogenous PELP1, and mutant expression is equivalent to GFP-tagged PELP1-WT clone (Fig. 3A). Both PELP1-WT and PELP1-MT are localized in the nuclear compartment in cells and migrated to the expected size on SDS-PAGE when detected using the GFP antibody (Fig. 3A A left panel, Supplementary Fig. S5). Western analysis using PELP1 phospho-specific antibody showed GFP-tagged wild-type PELP1 was phosphorylated during cell cycle progression, while PELP1-MT had no signs of phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S4C, right panel). As expected from previous studies, PELP1-WT expression increased cell proliferation as measured by using a Cell Titer-Glo assay and BrdU incorporation, while mutations in PELP1 diminished its ability to increase cell proliferation (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. S5B). We then analyzed the cell cycle progression of the PELP1-WT and -MT clones by flow cytometry and found that PELP1-WT expression contributed to increased G1-S progression, while mutation of the CDK sites in PELP1 diminished the number of cells entering S phase upon E2 stimulation (Fig. 3C). We then used a knockdown/replacement strategy to validate the effect of CDK phosphorylation on PELP1-mediated proliferation. ZR75 cells that stably express PELP1 shRNA were transfected with shRNA-resistant PELP1-WT or -MT expression vectors using nucleofector protocol (Amaxa) that achieved >90% transfection efficiency. After 48 h, transfected cells were allowed to proliferate with or without E2. Results showed PELP1-WT but not PELP1-MT enhanced E2-mediated proliferation. (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that phosphorylation by CDKs is biologically relevant for PELP1-mediated G1-S phase transition.

Figure 3.

CDKs-mediated phosphorylation is required for optimal PELP1 function in cell cycle. A, Western analysis of ZR75 cells stably expressing GFP-Vec, GFP-PELP1-WT and GFP-PELP1-MT. B, Cell proliferation capacity of parental ZR, PELP1-WT and PELP1-MT stable cells were analyzed after treating the cells with 10% serum (left panel) and with or without E2 (right panel) using Cell Titer-Glo assay. C, Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle phases in ZR-GFP, wild-type ZR-PELP-WT and mutant PELP1-MT pool clones was done and changes observed in S-phase cells are depicted by percentages. D, ZR75 cells that stably express PELP1 shRNA were transfected with shRNA-resistant PELP1-WT or -MT expression vectors by using nucleofector protocol. After 48 h, transfected cells were subjected to cell proliferation with or without estradiol (E2) and assayed for proliferation using Cell Titer-Glo assay. *, P<0.05, **, P<0.001.

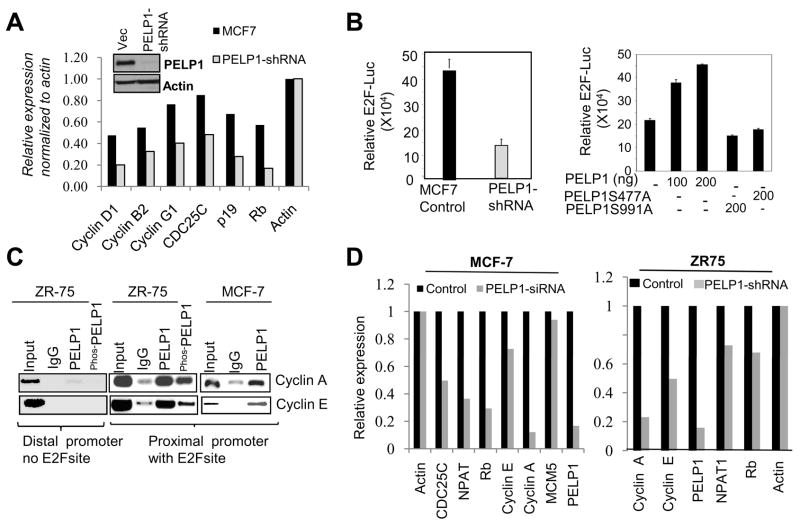

CDK-PELP1 axis modulates expression of E2F target genes

Since PELP1 is a pRb-binding protein and CDKs phosphorylate PELP1, we investigated whether CDKs phosphorylation of PELP1 aids E2F functions. First, we compared the expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression between MCF7 and MCF7-PELP1-shRNA stable cells using the Cell Cycle Microarray that contains 112 genes involved in cell cycle regulation. Target genes whose expression was differentially regulated (with at least a 2-fold difference) upon PELP1 depletion were identified. Down regulation of PELP1 substantially reduced the expression of a number of cell cycle genes including cyclin D1, pRb, cyclin B2 and CDC25C (Fig. 4A). We then examined whether PELP1 enhances E2F-mediated gene activation and whether CDK phosphorylation affects PELP1 activation of E2F functions by using an E2F luciferase reporter. PELP1 knockdown substantially reduced the E2F reporter gene activity (Fig. 4B, left panel). The cells with PELP1-WT overexpression had greater E2F luciferase reporter activity compared to vector transfected cells, while PELP1-MT that lacked CDK phosphorylation sites failed to enhance the E2F reporter activity (Fig. 4B, right panel). Chromatin immunoprecipitation demonstrated that phosphorylated PELP1 is recruited to the promoters of the E2F target gene promoters cyclin A and cyclin E both of which contain E2F binding sites (Fig. 4C). However mutation of CDK phosphorylation sites in PELP1 did not affected its recruitment over E2F target genes (Supplementary Fig. S5C). However, RTqPCR analysis showed that PELP1 knockdown significantly decreased the expression of several E2F target genes in both MCF7 and ZR75 cells (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the phosphorylation of PELP1 by CDKs plays a critical role in the expression of E2F target genes.

Figure 4.

CDK-dependent PELP1 phosphorylation modulates E2F transactivation functions. A, RNA isolated from MCF7-control and stable MCF7-PELP1 shRNA expressing cells were hybridized to the Human Cell Cycle microarray. Changes in the gene expression were analyzed using SABioscience software with actin as a control for normalization. Representative genes downregulated upon PELP1 depletion are shown. Expression of PELP1 in PELP1 shRNA clones is shown as an insert. B, MCF7 and MCF7-PELP1 shRNA cells were transfected with E2F-luciferase reporter along with E2F and DP1 plasmids, and luciferase activity was measured after 36 h (left panel). NIH3T3 cells were transfected with E2F-luc with E2F and DP1 plasmids and with or without PELP1-WT or PELP1-MT. Luciferase activity was measured after 36 h of transfection (right panel). C, Recruitment of PELP1 to E2F target genes promoter was analyzed by using the ChIP assay with MCF7 and ZR75 cells. D, MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with control or PELP1-specific siRNA (left panel). ZR75 cells were stably transfected with control or PELP1-specific shRNA (right panel). Total RNA was isolated and expression of classical E2F target genes was analyzed by real-time qPCR.

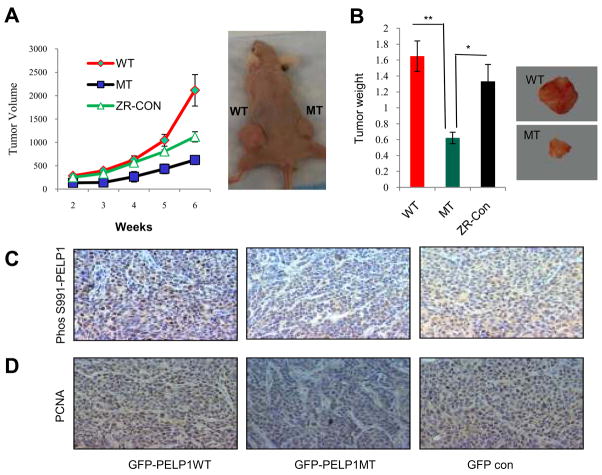

Mutation of CDK sites decreases PELP1 oncogenic potential in vivo

We used a nude mouse xenograft model to examine whether CDK phosphorylation of PELP1 is required for tumorigenic potential of breast cancer cells in vivo using model cells that express either PELP1 or PELP1-MT that lack CDK phosphorylation sites. Both vector-transfected and PELP1 WT-expressing cells formed tumors and these tumors grew linearly with time (Fig. 5A). However, PELP1-MTinjected sites had smaller tumors than those that developed in the controls (Fig. 5B). Compared to both mutant and parental ZR75 cells, ZR-PELP1-WT cells had more PELP1 phosphorylation at Ser991 (Fig. 5C) PCNA staining of the tumor sections revealed greater proliferation in thePELP1-WT xenograft tumors than in thePELP1-MT tumors (Fig. 5D). These results suggested that CDK phosphorylation of PELP1 is essential for optimal growth of E2-driven tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 5.

CDK phosphorylation is essential for PELP1 oncogenic function. A, Nude mice were implanted with E2 pellet were injected subcutaneously with ZR75-GFP or ZR75-PELP1-WT or ZR75-PELP1-MT cells and tumor growth was measured at weekly intervals. Tumor volume is shown in the graph (left panel). B, The average tumor weight is shown in the graph. Representative images of tumors are shown. Status of PELP1 phosphorylation (C) and PCNA expression as a marker of proliferation (D) was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.001.

Discussion

E2 is known to promote key cell cycle events like activation of CDK and hyper-phosphorylation of pRb in ER-positive breast epithelial cells, leading to increased rate of G1/S phase transition (25). Both CDK4 and CDK2 drive G1-S transition in the cell cycle and their expression is deregulated in tumors, indicating that phosphorylation of downstream effector proteins by CDKs is vital in tumorigenesis (3). We found that (a) PELP1 phosphorylation changes during cell cycle progression, (b) PELP1 interacts with the G1/S phase CDKs (both CDK4 and CDK2), (c) PELP1 couples E2 signaling to the E2F axis, (d) PELP1 is a novel substrate of CDKs, and (e) CDK phosphorylation plays a key role in PELP1 oncogenic functions. Collectively, these results suggests that phosphorylation of PELP1 by CDKs confer a growth advantage to breast epithelial cells and thus contribute to tumorigenesis by accelerating cell cycle progression.

Our results identified ER coregulator PELP1 as another novel substrate of CDKs and that its phosphorylation is essential for optimal cell cycle progression. CDKs phosphorylate PELP1 minimally at two distinct sites (Ser477 and Ser991) and these sites are phosphorylated by distinct CDK/cyclin complexes. We only validated Ser477 and Ser991 as in vivo sites for CDK4 and CDK2, respectively. It is possible that there may be additional putative minor sites that could be phosphorylated in vivo and we will explore those possibilities in future studies. Ser477 was previously identified as a site of phosphorylation of PELP1 in a large screen for EGF-stimulated phospho-proteins (30) and interestingly, EGF is shown to activate CDK4/cycD1 complexes (31). We speculate that Ser477 could be the site that facilitates ER/CDK4 cross talk, which occurs during mammary gland development and also in pathological settings including breast cancer progression. Reinforcement of Ser477 phosphorylation by CDK4/cycD1 and CDK2/cycA2, two kinases in two different cell cycle phases, is quite intriguing and may be important for unknown reasons.

Evolving evidence suggests that PELP1 may function as a large scaffolding protein, modulating gene transcription with protein-protein interactions. The N terminus of PELP1 interacts with ERα, pRb and Src (12). Our results suggest that the N terminus of PELP1 also harbors a binding site for CDK4 that facilitates PELP1 phosphorylation. We found that during cell cycle progression, PELP1 runs as 2–3 slower migrating bands and has a molecular weight greater than 160 kDa. Post-translational modification of PELP1 probably accounts for the multiple shifts of PELP1 observed on denaturing gradient gels during cell cycle progression, as previously described for pRb (32). We also demonstrated that PELP1-WT over expression but not PELP1-MT promoted progression of breast cancer cells to S phase, and that PELP1-MT significantly reduced E2-mediated in vivo tumorigenic potential. Our findings suggest that CDK phosphorylation of PELP1 plays a permissive role in E2-mediated cell cycle progression, presumably via its regulatory interaction with the E2F pathway.

Coregulators are often recruited by transcription factors to mediate epigenetic modifications at target gene promoters; for example, E2F utilizes coregulators like HCF1 (33) and KAP1 (34) to facilitate gene activation and repression, respectively. PELP1 can interact not only with histone-modifying acetylases and deacetylases, (35) but also with histone-modifying methyl-transferases and demethylases. A recent study identified PELP1 as a component of the MLL1 methyltransferase complex (36), and we have found that PELP1 functions as a reader of dimethyl-modified histones (37). Our results from the cell proliferation assays using PELP1-MT cells established the significance and role of CDKs phosphorylation of PELP1 in cell cycle progression. Collectively, these results suggest that PELP1 serves as a key coregulator that connects E2 signaling to the activation of E2F target genes probably by facilitating epigenetic changes, which will be addressed in future studies.

PELP1 expression is deregulated in metastastic tumors (13). PELP1 protein expression is an independent prognostic predictor of shorter breast cancer-specific survival and its elevated expression is positively associated with markers of poor outcome (14). Our data suggest that ER-CDK-PELP1 signaling plays a role in E2-mediated cell cycle progression and that the CDK deregulation commonly seen in breast tumors may play a role in metastasis by enhancing E2-mediated cell cycle progression via excessive phosphorylation of PELP1. Deregulation of both CDKs and PELP1 in breast cancer suggests that the modulation of PELP1 pathway by CDKs may represent a potential mechanism by which CDKs promotes breast tumorigenesis.

In summary, our data provide the first evidence demonstrating PELP1 as a novel substrate of CDKs. We also provide evidence to indicate that PELP1 phosphorylation by CDKs is essential for optimal E2 mediated cell cycle progression. On the basis of these findings, we predict that phosphorylation of PELP1 by CDKs confers a growth advantage to breast epithelial cells by activating the pRb/E2F pathway and thus contributes towards tumorigenesis by accelerating cell cycle progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Valerie Cortez, Monica Mann, Sreeram Vallabhaneni for help with the mice studies, UTHSCSA Core Facilities for FACS analysis and generating PELP1 antibodies. We thank Dr. Lu J for 4X-E2F-luciferase reporter plasmid.

This study was supported by the grants NIH-CA0095681 (RKV), DOD pre-doctoral grant W81XWH-09-1-0010 (BCN).

Reference List

- 1.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthet C, Klarmann KD, Hilton MB, Suh HC, Keller JR, Kiyokawa H, et al. Combined loss of Cdk2 and Cdk4 results in embryonic lethality and Rb hypophosphorylation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:563–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padmakumar VC, Aleem E, Berthet C, Hilton MB, Kaldis P. Cdk2 and Cdk4 activities are dispensable for tumorigenesis caused by the loss of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2582–93. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00952-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster JS, Henley DC, Ahamed S, Wimalasena J. Estrogens and cell-cycle regulation in breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:320–7. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prall OW, Rogan EM, Musgrove EA, Watts CK, Sutherland RL. c-Myc or cyclin D1 mimics estrogen effects on cyclin E-Cdk2 activation and cell cycle reentry. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4499–508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb J, Ladha MH, McMahon C, Sutherland RL, Ewen ME. Regulation of the functional interaction between cyclin D1 and the estrogen receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8667–75. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8667-8675.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prall OW, Rogan EM, Sutherland RL. Estrogen regulation of cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;65:169–74. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster JS, Henley DC, Bukovsky A, Seth P, Wimalasena J. Multifaceted regulation of cell cycle progression by estrogen: regulation of Cdk inhibitors and Cdc25A independent of cyclin D1-Cdk4 function. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:794–810. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.794-810.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prall OW, Sarcevic B, Musgrove EA, Watts CK, Sutherland RL. Estrogen-induced activation of Cdk4 and Cdk2 during G1-S phase progression is accompanied by increased cyclin D1 expression and decreased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor association with cyclin E-Cdk2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10882–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuman E, Ladha MH, Lin N, Upton TM, Miller SJ, DiRenzo J, et al. Cyclin D1 stimulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity independent of cdk4. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5338–47. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altucci L, Addeo R, Cicatiello L, Dauvois S, Parker MG, Truss M, et al. 17beta-Estradiol induces cyclin D1 gene transcription, p36D1-p34cdk4 complex activation and p105Rb phosphorylation during mitogenic stimulation of G(1)-arrested human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1996;12:2315–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Functional and biological properties of the nuclear receptor coregulator PELP1/MNAR. Nucl Recept Signal. 2007;5:e004. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajhans R, Nair S, Holden AH, Kumar R, Tekmal RR, Vadlamudi RK. Oncogenic Potential of the Nuclear Receptor Coregulator Proline-, Glutamic Acid-, Leucine-Rich Protein 1/Modulator of the Nongenomic Actions of the Estrogen Receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5505–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habashy HO, Powe DG, Rakha EA, Ball G, Macmillan RD, Green AR, et al. The prognostic significance of PELP1 expression in invasive breast cancer with emphasis on the ER-positive luminal-like subtype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balasenthil S, Vadlamudi RK. Functional interactions between the estrogen receptor coactivator PELP1/MNAR and retinoblastoma protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22119–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagpal JK, Nair S, Chakravarty D, Rajhans R, Pothana S, Brann DW, et al. Growth factor regulation of estrogen receptor coregulator PELP1 functions via Protein Kinase A pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:851–61. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J, Ruhf ML, Perrimon N, Leder P. A genome-wide RNA interference screen identifies putative chromatin regulators essential for E2F repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9381–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610279104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manavathi B, Nair SS, Wang RA, Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. Proline-, glutamic acid-, and leucine-rich protein-1 is essential in growth factor regulation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5571–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair SS, Mishra SK, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. Potential role of a novel transcriptional coactivator PELP1 in histone H1 displacement in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6416–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cos S, Fernandez F, Sanchez-Barcelo EJ. Melatonin inhibits DNA synthesis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells in vitro. Life Sci. 1996;58:2447–53. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vadlamudi RK, Balasenthil S, Sahin AA, Kies M, Weber RS, Kumar R, et al. Novel estrogen receptor coactivator PELP1/MNAR gene and ERbeta expression in salivary duct adenocarcinoma: potential therapeutic targets. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:670–5. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Nguyen D, Sahin AA, et al. Dynein light chain 1, a p21-activated kinase 1-interacting substrate, promotes cancerous phenotypes. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen MM, Jorgensen JT, Binderup T, Kjaer A. Tumor volume in subcutaneous mouse xenografts measured by microCT is more accurate and reproducible than determined by 18F-FDG-microPET or external caliper. BMC Med Imaging. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Euhus DM, Hudd C, LaRegina MC, Johnson FE. Tumor measurement in the nude mouse. J Surg Oncol. 1986;31:229–34. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930310402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster JS, Henley DC, Bukovsky A, Seth P, Wimalasena J. Multifaceted regulation of cell cycle progression by estrogen: regulation of Cdk inhibitors and Cdc25A independent of cyclin D1-Cdk4 function. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:794–810. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.794-810.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulman BA, Lindstrom DL, Harlow E. Substrate recruitment to cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by a multipurpose docking site on cyclin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10453–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loog M, Morgan DO. Cyclin specificity in the phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. Nature. 2005;434:104–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryu CK, Kang HY, Lee SK, Nam KA, Hong CY, Ko WG, et al. 5-Arylamino-2-methyl-4,7-dioxobenzothiazoles as inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and cytotoxic agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:461–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClue SJ, Blake D, Clarke R, Cowan A, Cummings L, Fischer PM, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor properties of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CYC202 (R-roscovitine) Int J Cancer. 2002;102:463–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, et al. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paternot S, Dumont JE, Roger PP. Differential utilization of cyclin D1 and cyclin D3 in the distinct mitogenic stimulations by growth factors and TSH of human thyrocytes in primary culture. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3279–92. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Lynch D, Furukawa Y, Griffin J, Piwnica-Worms H, et al. The product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene has properties of a cell cycle regulatory element. Cell. 1989;58:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyagi S, Chabes AL, Wysocka J, Herr W. E2F activation of S phase promoters via association with HCF-1 and the MLL family of histone H3K4 methyltransferases. Mol Cell. 2007;27:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, Rauscher FJ, III, Cress WD, Chen J. Regulation of E2F1 Function by the Nuclear Corepressor KAP1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29902–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi YB, Ko JK, Shin J. The transcriptional corepressor, PELP1, recruits HDAC2 and masks histones using two separate domains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50930–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dou Y, Milne TA, Tackett AJ, Smith ER, Fukuda A, Wysocka J, et al. Physical association and coordinate function of the H3 K4 methyltransferase MLL1 and the H4 K16 acetyltransferase MOF. Cell. 2005;121:873–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nair SS, Nair BC, Cortez V, Chakravarty D, Metzger E, Schule R, et al. PELP1 is a reader of histone H3 methylation that facilitates oestrogen receptor-alpha target gene activation by regulating lysine demethylase 1 specificity. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:438–44. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.