Abstract

We examined the developmental processes involved in peer problems among children (M age = 10.41 years) previously diagnosed with ADHD at study entry (N = 536) and a comparison group (N = 284). Participants were followed over a 6-year period ranging from middle childhood to adolescence. At four assessment periods, measures of aggression, social skills, positive illusory biases (in the social and behavioral domains), and peer rejection were assessed. Results indicated that children from the ADHD group exhibited difficulties in each of these areas at the first assessment. Moreover, there were vicious cycles among problems over time. For example, peer rejection was related to impaired social skills, which in turn predicted later peer rejection. Problems also tended to “spill over” into other areas, which in turn compromised functioning in additional areas across development, leading to cascading effects over time. The findings held even when controlling for age and were similar for males and females, the ADHD and comparison groups, and among ADHD treatment groups. The results suggest that the peer problems among children with and without ADHD may reflect similar processes; however, children with ADHD exhibit greater difficulties negotiating important developmental tasks. Implications for interventions are discussed.

Peer rejection is pervasive among children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), characterizing 52 to 82 percent of children with the disorder (Hoza, Mrug et al., 2005; Pelham & Bender, 1982), depending on the definition of rejection and the sample employed. Of great concern, peer rejection develops quickly in new social groups (Erhardt & Hinshaw, 1994), and, once established, is highly resistant to change. Even state-of-the-art intervention strategies that are successful at improving functioning in other areas have not been successful at normalizing the peer functioning of children with ADHD (Hoza, Gerdes et al., 2005). These difficulties characterize children with ADHD of both sexes and begin at an early age (e.g., age 7; Hoza, Mrug et al., 2005), with the strong potential of depriving these children of important developmental opportunities with peers.

Given the severe and persistent peer problems evident among children with ADHD, an important goal is to identify the processes that exacerbate or ameliorate ADHD children’s risk for poor relationships with peers. To address this question, we adopted a developmental psychopathology approach (Cicchetti & Cohen, 2006; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002; Sroufe, 1997), and applied it to a large existing sample that includes both children previously diagnosed with combined type ADHD, and a comparison group. A central tenet of this approach is that consideration of normal developmental processes is essential in understanding the emergence of disorder, associated impairments, and accumulating comorbidities over the life course; in effect, maladaptive functioning or disorder results from a failure to successfully negotiate developmentally-appropriate tasks (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). One implication of this approach is that comparisons to normative samples are important for understanding the processes involved in the emergence of peer problems among children with ADHD. A second implication is that the peer problems among children with ADHD may be the result of unsuccessful attempts to navigate developmental challenges. A third implication is that successful intervention may prevent the onset of accumulating difficulties.

In their evaluation of psychosocial developmental tasks, Masten and Coatsworth (1998) identified broad areas of competence and the developmental progression of adaptation typical in these areas. For example, one important area of functioning is engaging in socially appropriate conduct. During early childhood, children must develop strategies for self-control and learn to comply with the requests of others. By middle childhood, they are expected to follow societal rules regarding moral and prosocial behavior, including inhibiting aggressive and delinquent behaviors and engaging in positive behaviors such as helping others. Finally, during adolescence, they are expected to internalize rules regarding socially appropriate conduct and to engage in such behaviors in the absence of direct supervision (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). Importantly, evidence suggests that children with ADHD fail to exhibit this typical developmental progression and struggle in these areas of functioning across developmental periods. For example, they display elevated levels of aggressive and delinquent behaviors (Hoza, Owens, & Pelham, 1999) and perform less skillfully with peers (Hinshaw, 2002), suggesting that they may be relatively unsuccessful in negotiating these important developmental tasks.

Another important developmental task is the formation of a cohesive sense of self (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). One aspect of this process is developing an accurate view of one’s own abilities. In fact, during early childhood, children tend to overestimate their competencies in a variety of domains (Harter & Pike, 1984). By early adolescence, typical children are fairly accurate in their reports of their abilities (Harter, 1982; Marsh et al., 1998). However, many children with ADHD continue to exhibit inflated self-perceptions in areas such as social and behavioral competence (relative to actual competence as rated by teachers and parents) into early adolescence in that they approach normative self-perceptions while having actual competence below the norm (e.g., Hoza et al., in press). This suggests that these children have failed to negotiate this important developmental task (for additional details regarding developmental changes in biases across adolescence in this sample, see Hoza et al, in press).

Finally, a third salient developmental task that gains even greater prominence during middle childhood and into adolescence is the formation of friendships and getting along with peers (Berndt, 1996; Bukowski & Kramer, 1986; Hartup, 1992; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). A number of studies have demonstrated that children with ADHD have lower social preference and fewer friendships (Hoza, Mrug et al., 2005) than do agemates. Even when friendships are formed, these are less stable and of poorer quality than those of typically developing peers (Blachman & Hinshaw, 2002).

Although the peer problems of children with ADHD may simply reflect a failure to establish successful relationships with peers, it is possible that these difficulties also result from failures to negotiate other important developmental tasks across the lifespan. The hypothesis that compromised functioning in one area has implications for competence in other areas is not new. Moreover, investigators have recently adopted a “developmental cascades” analytical approach to demonstrate how failures in one area of functioning (e.g., social, academic, behavioral) can “spill over” into other areas across development (Burt et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2005). A developmental cascades analysis involves testing the cross-lagged associations among multiple areas of functioning over time. Importantly, these analyses control for the stability of each area of functioning across time as well as within-time correlations among variables. As such, this approach controls for the fact that functioning in one area is often correlated with functioning in other areas (by controlling for within-time correlations) and thus provides a strong empirical test of longitudinal associations among areas of functioning across development. For example, Masten and colleagues (2005) demonstrated that externalizing problems at age 10 were associated with lower academic competence at age 17 and that academic failures at age 20 predicted internalizing problems at age 30. These findings highlight how failures in one area can “spill over” into functioning in other areas across development, and also offer important insights about potential points for effective intervention.

A developmental cascades approach may provide insight regarding why peer problems are so pervasive, severe, and persistent among children with ADHD. For example, problems with inhibiting aggression, developing appropriate social skills, and developing accurate self-perceptions may all have implications for a child’s status in the peer group. In fact, a number of studies with normative samples have demonstrated that aggressive behavior is associated with peer problems such as rejection (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Ostrov & Crick, 2007; Vaillancourt & Hymel, 2006). Aggression may be associated with rejection for a number of reasons. First, children are likely to find aggression by peers objectionable, leading aggressive children to be increasingly disliked over time. Consistent with this perspective, researchers have demonstrated that aggressive behaviors predict later peer rejection (e.g., Hay et al., 2004; Little & Garber, 1995; Ostrov & Crick, 2007; Pope & Bierman, 1999). One longitudinal study indicated that childhood aggression in a sample of ADHD youth was inversely related to self-reported social acceptance in adolescence five years later (Bagwell, Molina, Pelham, & Hoza, 2001). However, rejection also may lead to aggression over time. For example, some children might respond to dislike and rejection by others with aggressive conduct. In fact, evidence suggests that rejection is associated with later aggression (Dodge et al., 2003; Hay et al., 2004; Ialongo, Vaden-Kiernan, & Kellam, 1998; Kupersmidt, Burchinal, & Patterson, 1995; Pettit, Clawson, Dodge, & Bates, 1996). Importantly, although some of these studies control for initial levels of the outcome variable when exploring longitudinal associations (e.g., Dodge et al., 2003; Ialongo et al., 1998), others do not (e.g., Ostrov & Crick, 2007; Pope & Bierman, 1999). Nevertheless, taken together, these studies suggest that a vicious cycle seems likely: Aggressive conduct may evoke high levels of peer rejection. In turn, rejection by peers may lead to even greater levels of aggression.

Failures to develop appropriate social skills may place children with ADHD at additional risk for rejection by peers. Social skills are defined as behaviors and abilities that allow children to succeed on social tasks, and include perspective-taking abilities, the tendency to initiate and maintain positive social exchanges with others, and engaging in socially positive and prosocial behaviors (see Rubin et al., 2006). A number of studies have demonstrated that poor social skills are associated with peer rejection (e.g., Harrist et al., 1997; Newcomb et al., 1993) whereas positive social skills such as friendly and cooperative behavior are associated with peer popularity (Newcomb et al., 1993; Rubin et al., 1998; Warden & Mackinnon, 2003). In one study of children with ADHD, behavioral frequencies of helping peers and following activity rules predicted small but significant positive changes in peer sociometric variables (such as acceptance and rejection) over the course of a summer treatment program (Mrug, Hoza, Pelham, Gnagy, & Greiner, 2007). The association between impaired social skills and peer rejection makes theoretical sense. Socially skilled children will have advantages in forming positive social relationships with their peers. In contrast, children with poor social skills will likely fail in their attempts at eliciting positive regard from their peers and, in their disappointment or in desperate attempts to elicit positive peer regard, may do things (such as enviously attacking more successful peers or unwarranted bragging) that lead to rejection by peers. Consistent with this view, one common component of interventions for rejected children is social skills training (see Bierman, 2004).

It is also possible that peer rejection impairs the development of appropriate social skills, leading to a vicious cycle between functioning in these areas. In fact, developmental psychologists have long emphasized the importance of social interaction in the development of social skills (Hartup & Sicilio, 1996; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Peer interaction may be essential for learning social norms, developing social-cognitive abilities, and practicing social skills (see Harrist et al., 1997). In fact, evidence suggests that close emotional ties to peers are associated with perspective taking skills (e.g., Hughes & Dunn, 1998; Maguire & Dunn, 1997), and longitudinal work indicates that peer rejection in childhood is associated with lower sociability in adulthood, although these findings were no longer significant when controlling for childhood social prominence (Bagwell et al., 1998). Overall, these findings suggest that rejected children may have fewer opportunities to interact with peers and thus learn and practice social skills, leading to impaired social skills and further rejection over time.

Finally, inflated self-perceptions regarding competence might place children at risk for rejection by peers via their influence on peer-based behaviors. Children who report high levels of competence relative to external criteria such as peer or teacher reports are considered to have overly positive self-perceptions (e.g., Diamantoppoulou et al., 2008; Hoza et al., 2004; Hoza et al. 2002). A number of researchers have found that children with these positively biased self-perceptions in areas such as social and behavioral competence are more likely than their peers to engage in aggressive behaviors (Diamantopoulou et al., 2008; Hoza et al., in press; Hymel et al., 1993; Rudolph & Clark, 2001; Zakriski & Coie, 1996), although these studies tend to be cross-sectional in design (for an exception, see Hoza et al., in press). Baumeister and colleagues (1996) argued that individuals with inflated self-perceptions may choose to behave aggressively against peers who challenge their positive self-views. In addition, Hoza and colleagues (2009) have proposed that accurate self-perceptions are essential in learning appropriate behaviors in the peer group. For example, children with behavioral problems and poor social skills who nonetheless maintain positive self-perceptions in these domains will likely be unmotivated to alter their behavior, leading to sustained problems across development. Thus, we expected that overly positive self-perceptions in the social and behavioral domains would be associated with the development of negative peer-based behaviors (i.e., poor social skills, increased aggression).

Previous research has generally explored domain-specific positively biased self-perceptions, such as biases in the social and behavioral domains (e.g., Hoza et al., in press). This approach has been adopted in part because self researchers have argued that self-views often vary across competence domains (Harter, 1999). Moreover, recent research with this sample has provided evidence of distinct trajectories of change in positive biases in the social and behavioral domains across development (Hoza et al., in press), further bolstering the case that these biases should be considered separately. It is possible, for example, that biases in the social and behavioral domains will have different effects on peer-based behavior. In fact, given Hoza et al.’s (2009) proposal that positively biased self-perceptions interfere with learning appropriate behaviors in the peer group, we expected that biases in the social domain would be more strongly related to poor social skills whereas biases in the behavioral domain would be more strongly related to aggressive conduct. For example, children with inflated views of their social competence should be especially unlikely to work to improve their social skills whereas children with inflated views of their behavioral competence should be especially unlikely to work to reduce their involvement in disruptive behaviors such as aggression. Finally, we expected that these negative behaviors would be associated with rejection by peers, suggesting an indirect role of positively biased self-perceptions in peer problems among children with ADHD. In fact, recent work (Kaiser, Hoza, Pelham, Gnagy, & Greiner, 2008) demonstrated that overly positive self-perceptions mediated the relation between ADHD status and frequency of socially problematic behaviors in a summer program setting.

Although overly positive self-perceptions may place children at risk for aggression and poor social skills, it is possible that negative peer-based behaviors also may lead to the development of positively biased self-perceptions. In fact, researchers have proposed that inflated self-perceptions may serve a self-protective function for some individuals (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1996). From this perspective, individuals with low competence may learn to cope with these failures by rejecting others’ evaluations of them and insisting that they are in fact successful in these domains. Thus, children with poor social skills and high levels of aggressive conduct may develop positively biased self-perceptions in an effort to bolster their self-views.

Overall, these findings suggest that peer rejection may result from vicious cycles and cascading effects due to failures to successfully negotiate important developmental tasks. Specifically, failures to learn socially appropriate behavior (e.g., inhibiting aggression and developing social skills) may place children at risk for rejection by peers. In addition, children who are unsuccessful in developing accurate self-views may be at risk for rejection via changes in their peer-based behavior (e.g., increased aggression). Importantly, reciprocal effects are likely to occur, with rejection by peers leading to aggressive conduct and low social skills. Vicious cycles are also expected, in which failures in one area lead to problems in other areas, which in turn exacerbate problems in the original area of functioning. Given the documented difficulties negotiating each of these developmental tasks among children with ADHD, the relatively high levels of peer rejection among these children may in part reflect cascading effects from failures in other areas of functioning.

Hypotheses

This study tested the hypothesis that peer rejection among children with ADHD results from failures to successfully negotiate important developmental tasks, including inhibiting aggression, learning appropriate social skills, and developing accurate self-views. Data to test these predictions were drawn from a longitudinal sample that included both children with ADHD and a comparison group. Assessments of peer rejection, aggression, social skills, and positively biased self-perceptions were available at four assessment periods across a 6-year time span. We conducted a series of four nested model comparisons to test study hypotheses. Each successive model included all paths estimated in the previous model. A separate set of models were conducted for positive illusions in the social and behavioral domains, respectively, since self-perceptions are thought to be domain-specific (Harter, 1985, 1988), and to make findings comparable to previous research (e.g., Hoza et al., 2002, 2004).

In Model 1, we tested whether ADHD status (initial assignment to either the ADHD or comparison group) predicted peer rejection, aggressive behavior, poor social skills, and positively biased self-perceptions at the first assessment period given evidence that ADHD is associated with impairments in each of these areas of functioning. Consistent with previous cascade analyses (e.g., Burt et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2005), we calculated stability in each area of functioning and within-time correlations across areas. We expected moderate to high stability of study variables across time, and we expected that, within each time point, functioning in each area would be significantly correlated with functioning in the other three areas. Model 2 estimated the cross-lagged paths between rejection, aggression, and social skills given strong evidence suggesting reciprocal associations among these three variables. We expected that both aggression and impaired social skills would be associated with increases in rejection over time. In addition, we expected that peer rejection would lead to increases in aggression and decreases in social skills. Finally, although not central to our study hypotheses, we expected that poor social skills and aggression would exhibit reciprocal effects across development, given evidence that aggressive children lack social skills such as the ability to generate prosocial goals (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994).

In Model 3, we estimated the bidirectional association between positively biased self-perceptions (in the social and behavioral domains) and both aggression and social skills across the first time lag (from Time 1 to Time 2). We focused on this first time lag to examine whether the effects of self-perceptions on behavior are especially likely during early adolescence, when a focus on others’ views of the self becomes especially salient (see Harter, 1999). We expected that biases in the social domain would be more strongly related to social skills whereas biases in the behavioral domain would be more strongly related to aggression. In Model 4, we estimated cross-lagged paths between positively biased self-perceptions and both aggression and social skills across the remaining two time lags (Time 2 to Time 3 and Time 3 to Time 4). This final model was exploratory, as we did not have specific predictions about whether biased self-perceptions would be associated with aggression and social skills during later adolescence. Finally, we conducted additional analyses to test whether our findings remained when controlling for age and whether significant paths differed by sex, ADHD status (ADHD vs. comparison group), or by previous experiences of treatment among the ADHD sample.

Method

Participants

A total of 820 8–13 year-old children (M = 10.41 years, SD = .93) from the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) participated in this study. Of these 820 participants, 536 were diagnosed previously with ADHD. Specifically, two years prior to assessments for the current study, a total of 579 participants were recruited for the MTA intervention study for children with ADHD. At this time, these children were diagnosed as ADHD-Combined Type by MTA staff using procedures outlined in Hinshaw et al. (1997). The sample was selected to be widely representative of children seen in clinical practice (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999); as a result, a number of ADHD participants had comorbid disorders (e.g., 39.9% had oppositional defiant disorder and another 14% had conduct disorder, see MTA Cooperative Group, 1999). In total, 536 of the 579 ADHD participants had data on relevant study measures for at least one of the assessment periods for this study and were thus included in analyses.

Two years prior to their participation in the present study, the ADHD participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment conditions: (1) Medication Management; (2) Behavior Therapy; (3) Combined Treatment (treatment including both Medication Management and Behavior Therapy); or (4) Community Care (families selected treatment(s) from options available in their communities, including the possibility of no treatment). Following the treatment phase, MTA children participated in a 10-month follow-up phase. During this period, no further treatments were provided by the MTA; however, participants were free to seek treatment in the community.

At the 24 month assessment (i.e., the start of the present study), a comparison group of 289 were recruited from the same schools and grades as the ADHD sample. These children were selected randomly, in the same sex proportions as the ADHD group, and were intended to be broadly representative of children in the local communities. Hence, they were not screened for ADHD or other problems, but only for factors that might limit their valid participation (e.g., non-English speaking; low IQ). Of these 289 participants, 284 (231 males and 53 females) had data on relevant study measures for at least one assessment point and were thus included in study analyses. In sum, the present study included 820 participants (536 ADHD and 284 from the comparison group).

Data for this study were collected at 4 different time points. The first time point analyzed represents the 24 month assessment in the main MTA study. For purposes of the present investigation, this first time point is referred to as Time 1. Three follow-up assessments also were conducted: a 1 year follow-up (Time 2, 3 years after original MTA baseline), a four-year follow-up (Time 3, 6 years after original baseline), and a 6-year follow-up (Time 4, 8 years after original baseline).

All children who had completed relevant study measures during at least one assessment period were included. Teacher reports of children’s behavior at Time 4 were only included in analyses if children were still in school at this assessment period. Sixty-two percent of the sample was Caucasian, 18% African-American, 11% Hispanic or Latino, 7% was biracial, and 2% was “other”. The average household income of participants was $40,001–$50,000 (income ranged from less than $10,000 to $75,000 or more).

Positive Illusory Biases

To assess participants’ positive illusory biases, participants and teachers completed measures of competence in both the social and behavioral domains. These domains were selected given evidence that positively biased self-perceptions in these domains are associated with peer-based behavior such as aggression (e.g., Hoza et al., in press). Participants rated their perceptions regarding their social acceptance (e.g., “some kids are popular with other kids their age…”) and behavioral conduct (e.g., “some kids usually get in trouble because of things they do…”, reverse-scored) on a scale of one to four using the appropriate subscales from the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1985) at Time 1 and Time 2 of the study and the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988) at Time 3 and Time 4. Scores for items in each subscale were averaged to yield a competence score in each domain, with higher scores reflecting higher self-reported competence. A subset of participants (N = 94) completed the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adults (Messer & Harter, 1989) at Time 4, because they were 18 years old. This measure is substantially different from the measure for children and adolescents; therefore these scores were excluded from analyses and treated as missing data. In the present sample, the internal consistencies of both the self-reported social acceptance and the behavioral conduct scales were acceptable at all time points (αs ranged from .72 to .80).

Teachers rated participants’ social acceptance (e.g., “this child is popular with others his/her age…”) and behavioral conduct (e.g., “this child is usually well-behaved…”) on a scale of one to four using the teacher version of the Harter (1985) scale for children at Time 1 and Time 2 and the teacher version of the Harter (1988) scale for adolescents at Time 3 and Time 42. Scores in each subscale were averaged to yield a competence scale in each domain. When more than one teacher reported on a participating child, the scores from all teachers were averaged to create a single teacher-report score. The internal consistencies of both subscales were acceptable at all time points (αs ranged from .81 to .95).

Positive illusory bias scores were calculated by subtracting teacher reports of participants’ competence in the social and behavioral domains from children’s own self-reported competence from the parallel domain. Thus, positive bias scores reflected inflated self-perceptions whereas negative scores reflected an underestimation of one’s competence. Because of missing self or teacher reports, 16% of the sample was missing positive illusory bias scores regarding social and behavioral competence at Time 1. Also, because of missing data and/or attrition, 20%, 31%, and 36% of the sample was missing positive illusory bias scores at Times 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Of note, despite debate in the literature regarding the use of difference scores (for reviews and discussions of this debate, see Colvin, Block, & Funder, 1996; Owens et al., 2007), we chose to operationalize bias in this manner for the following reasons. First, suggested alternatives to difference scores (e.g., residual scores) have equally serious statistical limitations, plus the added problem of interpretive difficulty (Colvin, Block, & Funder, 1996). Second, although difference scores have been criticized on the basis of lower reliability, residual scores often have comparable or even lesser reliability than difference scores (Rogosa, 1988, as cited in Colvin et al., 1996). As noted previously, “unreliability will only attentuate and never spuriously inflate correlations” (Colvin et al., 1996, p. 1253); hence the resultant effect of unreliability of difference scores would be to underestimate relations among variables. Importantly, then, when significant relations are found, they are likely to be meaningful. Third, separately analyzing components of a difference scores, such as self and teacher reports of competence, tests conceptually different questions than analysis of the difference score itself (Tisak & Smith, 1994a, b) and, therefore, is not considered a conceptually suitable alternative. For these reasons, we retained difference scores as measures of bias.

Bivariate correlations between biases in the social and behavioral domain were moderate in size (correlations ranged in size from .30 to .45 across the four assessment points), suggesting that these biases are related but distinct constructs.

Aggressive and Antisocial Behavior

Parents reported on participants’ aggressive and antisocial behaviors using the DSM-IV Conduct Disorder Checklist (Hinshaw et al., 1997). This 38-item instrument assesses the frequency of aggressive behaviors (e.g., “hit other children”) and antisocial behaviors (e.g., stealing, lying, property destruction) on a scale of one (never) to four (often). Items were averaged to yield an overall score, hereafter (for simplicity) referred to as “aggression.” Most participants (93% of participants with parent reports of aggression at Time 1) had reports from the biological mother; however many participants had reports from biological fathers (49% at Time 1), stepfathers (5% at Time 1), adoptive mothers (2% at Time 1), or other caretakers (e.g., foster mothers; 4% at Time 1). Given the relatively high correlation between scores by different reporters (e.g., r = .59, p < .001 between biological mothers and biological fathers at Time 1), scores were averaged to create one caretaker-report score if more than one caretaker reported on the participant. The internal consistency of this scale was good (αs ranged from .84 to .89). Because of missing data and/or attrition, 6%, 11%, 15%, and 29% of the sample was missing aggression scores at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Social Skills

Teachers provided reports of participants’ social skills using the Social Skills Rating System – Teacher Report2 (Gresham & Elliott, 1990). The K-6 and 7–12 versions were used based on the grade of the participant at each assessment period. Teachers rated how often participants engaged in a variety of socially desirable behaviors for the social conduct factor of this measure (10 items; e.g., “cooperates with peers without prompting”) on a scale from 0 (never) to 2 (very often). Although other subscales are available from this measure (e.g., problem behaviors), only the social conduct subscale was included given our focus on social skills. When more than one teacher reported on a participating child, the scores from all teachers were averaged to create a single teacher-report score. Internal consistency of this scale was good at all time points (alphas ranged from .82 to .90). Because of missing data and/or attrition, 9%, 19%, 32%, and 42% of the sample was missing social skills scores at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Peer Rejection

Teachers provided reports of participants’ rejection in the classroom using the Dishion Social Acceptance Scale (Dishion, 1990).2 Previous research has demonstrated moderate correlations between this scale and peer-based sociometric scores (Dishion, 1990), and recent research has used this measure to assess social functioning in the peer group (e.g., Owens et al., 2009). Teachers rated the proportion of children who disliked or rejected each child on a scale from 1 (very few: less than 25%) to 5 (almost all: more than 75%). Because of missing data and/or attrition, 12%, 19%, 30%, and 42% of the sample was missing rejection scores at Times 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses for the present study were conducted using path analysis MPlus version 5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Examination of the study variables indicated significant skewness for aggression and rejection (skewness for these variables ranged from 1.51 – 3.46; Kline, 2005); thus, the maximum likelihood-robust (MLR) estimator was used to accommodate the non-normality of these variables (see Chapter 15 in Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Maximum likelihood estimation procedures were used to accommodate missing data. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were used to evaluate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). In general, a cutoff value of .06 or lower for the RMSEA and .95 or higher for the CFI suggest good fit with the observed data (Hu & Benter, 1999), although lower thresholds are generally adopted for acceptable fit (e.g., CFI = .90, Little et al., 2003; see Hu & Benter, 1999). Relative fit for models was compared using a chi-square difference test for non-normally distributed data (Satorra, 2000).

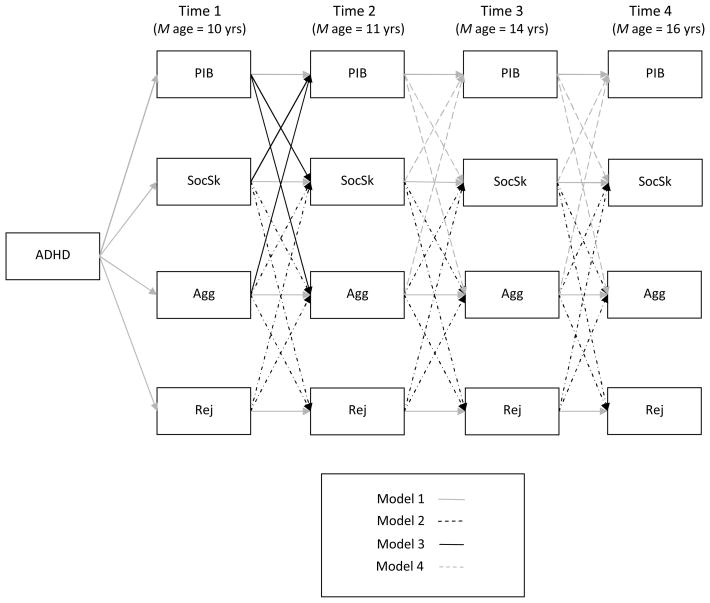

For measures of positive illusory biases in the social and behavioral domain, respectively, a series of four theoretically-informed nested models were compared to assess which model provided the best fit. Model 1 (the baseline model) included within-time correlations (i.e., positive illusory biases, aggression, social conduct, and rejection) and first-lag continuity (e.g., continuity between aggression at T1 and T2). Model 2 included cross-lagged paths among social conduct, aggression, and rejection across the four time points. Model 3 allowed the cross-lagged paths between positive illusory biases and social conduct and aggression between Time 1 and Time 2 to vary. Finally, Model 4 allowed the remaining cross-lagged paths between positive illusory biases and social conduct and aggression to vary (i.e., between Time 2 and Time 4). In all models, ADHD status (initial classification in ADHD versus comparison group) predicted positive illusory biases, aggression, social conduct, and aggression at Time 1. Figure 1 depicts the paths freed in the nested models. Analyses were run separately by positive illusory domain (i.e., social and behavioral), given theory suggesting that self-concept is distinct across domains (Harter, 1985, 1988) and given the moderate correlation of positive illusions in the social and behavioral domains in the present sample, r = .45, p < .001. It is important to note that cross-lagged associations control for cross-sectional correlations and previous levels of functioning; thus, significant cross-lagged associations suggest that competence in one area predicts changes in functioning in another over time.

Figure 1.

Freely estimated paths for nested models. PIB = Positive Illusory Biases;. SocSk = social skills; Agg = aggressive behavior; Rej = peer rejection. All models include within-time correlations and the paths from the previous models. Solid grey lines represent stability estimates. Dashed black lines represent cross-lagged paths between social skills, aggression, and rejection. Solid black lines represent cross-lagged paths between positive illusions and social skills and aggression at the first time lag. Gray dashed lines represent cross-lagged paths between positive illusions and social skills and aggression at the second two time lags.

Results

Missing Data

Six-hundred and nineteen of the 820 participants (76% of the sample) remained in the study through Time 4, in terms of providing data on at least some measures at this time point. We examined whether there were differences between participants who remained in the study compared to participants for whom data were not available (or who were lost to attrition) by Time 4. Results indicated that attrition was not significantly associated with illusory biases in the social domain at Time 1, F(1, 690) = 2.28, p = .13, illusory biases in the behavioral domain at Time 1, F(1, 692) = 2.60, p = .11, peer rejection at Time 1, F(1, 720) = .93, p = .34, social skills at Time 1, F(1, 744) = 1.66, p = .20, family income, F(1, 798) = 2.68, p = .10, or race (1=Caucasian; 2=African-American; 3=Other), χ2(2, N = 820) = 2.17, p = .34. However, attrition was associated with aggressive conduct at Time 1, F(1, 768) = 6.15, p < .05, and ADHD status, χ2(1, N = 820) = 7.10, p < .01. Specifically, participants with ADHD and those with higher levels of aggression were less likely to have continued in the follow-up than were their peers. Among ADHD participants, attrition was also associated with treatment group, χ2(3, N = 536) = 12.09, p < .01; participants in the Combined Treatment and Behavioral Therapy were more likely to remain in the study than participants in the Medication Management and Community Care treatment groups.3 In addition, there was a significant association between attrition and age, F(1, 749) = 32.67, p < .01, with older participants being less likely to have data available at Time 4. Maximum likelihood estimation procedures were used to accommodate missing data.

Characteristics of the MTA and Comparison Groups

Analyses of variance comparing participants in the ADHD and the comparison groups at each time point indicated that children in the ADHD sample exhibited elevated levels of dysfunction across the six years of the study (see Table 1). Specifically, ADHD participants exhibited lower social skills at Time 1, F(1, 744) = 118.10, p < .001, Time 2, F(1, 659) = 125.70, p < .001, Time 3, F(1, 557) = 50.15, p < .001, and Time 4, F(1, 471) = 20.91, p < .001. In addition, participants with ADHD also were more rejected than their peers at Time 1, F(1, 720) = 69.68, p < .001; Time 2, F(1, 664) = 59.40, p < .001; Time 3, F(1, 571) = 38.31,p < .001; and Time 4, F(1, 473) = 39.40, p < .001. In addition, previous research with this sample has demonstrated that the children diagnosed with ADHD exhibited higher levels of ADHD symptoms, symptoms of depression, and aggression across the 4 assessment periods (see Hoza et al., in press).

Table 1.

Means (and SDs) of study variables for ADHD and Comparison Participants

| Study Time |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| ADHD | Comparison | ADHD | Comparison | ADHD | Comparison | ADHD | Comparison | |

| Social Acceptance | ||||||||

| Child Report | 3.15 (.71) | 3.23 (.69) | 3.27 (.66) | 3.33 (.62) | 3.22 (.66) | 3.38 (.55) | 3.22 (.67) | 3.40 (.50) |

| Teacher Report | 2.30 (.84) | 3.08 (.83) | 2.41 (.81) | 3.05 (.81) | 2.50 (.76) | 2.87 (.68) | 2.57 (.68) | 2.92 (.66) |

| Illusory Biases | .76 (1.01) | .14 (.95) | .82 (.87) | .28 (.86) | .71 (.85) | .51 (.69) | .64 (.78) | .50 (.77) |

| Behavioral Conduct | ||||||||

| Child Report | 3.13 (.69) | 3.39 (.58) | 3.16 (.63) | 3.39 (.62) | 2.86 (.58) | 3.13 (.60) | 2.86 (.60) | 3.15 (.61) |

| Teacher Report | 2.40 (.95) | 3.28 (.86) | 2.60 (.91) | 3.49 (.71) | 2.81 (.82) | 3.39 (.64) | 2.93 (.79) | 3.37 (.67) |

| Illusory Biases | .71 (1.09) | .13 (.91) | .55 (.99) | −.10 (.82) | .05 (.89) | −.27 (.75) | −.06 (.87) | −.22 (.72) |

| Social Skills | 1.10 (.40) | 1.43 (.40) | 1.12 (.39) | 1.45 (.36) | 1.19 (.34) | 1.39 (.32) | 1.27 (.35) | 1.42 (.34) |

| Rejection | 2.01 (1.22) | 1.32 (.77) | 1.87 (1.10) | 1.27 (.69) | 1.69 (.94) | 1.25 (.54) | 1.49 (.75) | 1.12 (.38) |

| Aggression | 1.16 (.18) | 1.06 (.12) | 1.16 (.18) | 1.05 (.07) | 1.15 (.20) | 1.06 (.15) | 1.15 (.21) | 1.05 (.09) |

Note. Higher scores reflect higher levels of competence, biases, social skills, rejection, and aggression.

As expected, ADHD children were more likely than their peers to have a positive illusory bias in both the social and behavioral domains. Hoza et al. (2004) found that ADHD children exhibited elevated biases in the social and behavioral domains at Time 1. Analysis of variance tests indicated that ADHD children also exhibited elevated biases in the social domain at Time 2, F(1, 652) = 61.39, p < .001, Time 3, F(1, 563) = 8.43, p < .01, and Time 4, F(1, 427) = 3.90, p < .05. ADHD children also exhibited elevated biases in the behavioral domain at Time 2, F(1, 654) = 76.28, p < .001, and Time 3, F(1, 557) = 18.64, p < .001, but not at Time 4, F(1, 426) = 3.82, p = .051 (although this effect approached statistical significance). Additional details regarding developmental change in biases in the social and behavioral domain with this sample are available in Hoza et al. (in press).

Analyses were also conducted to examine whether children with ADHD who had received each of the four different MTA treatments (Medication Management; Behavior Therapy; Combined Treatment; or Community Care) differed on study variables at Time 1. A multivariate ANOVA with study variables at Time 1 serving as the dependent variable and MTA treatment group serving as the independent variable was significant, F(15, 1197) = 1.84, p < .05. Univariate tests indicated that treatment group was associated with positive illusions in the behavioral domain, F(3, 401) = 4.44, p < .05, and social skills, F(3, 403) = 3.48, p < .05.4 Tukey post-hoc tests revealed that participants in the Combined Treatment had lower behavioral biases at Time 1 than those exhibited by participants who received Behavioral Therapy. In addition, participants in the Combined Treatment exhibited higher levels of social skills at Time 1 when compared to those in the Medication Management treatment. No other effects were significant.

Social Illusory Biases

Nested model comparisons were conducted to evaluate the fit of each model including positively biased self-perceptions in the social domain. Results, presented in Table 2, indicated that Model 1 provided poor fit to the data. However, the addition of the paths in Model 2 and Model 3 both provided significant improvement in model fit. In contrast, addition of the paths on Model 4 did not result in better model fit; as a result, Model 3 was selected as the final model (CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06). These results indicate that the addition of cross-lagged paths between biases in the social domain and the other three areas of functioning improved model fit only from Time 1 to Time 2.

Table 2.

Model Comparisons for Nested Models (final model in bold)

| Biases Domain | Model | No. of Cross-Domain Paths | df | C | χ2 | CFI | RMSEA | Model Comparison | cd | Δdf | Δ χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | 1 | 0 | 96 | 1.17 | 434.23 | .875 | .066 | 2 vs. 1 | 1.226 | 18 | 132.39 | < .0001 |

| 2 | 18 | 78 | 1.16 | 289.78 | .922 | .058 | 3 vs. 2 | 1.139 | 4 | 30.82 | <.0001 | |

| 3 | 22 | 74 | 1.16 | 268.23 | .928 | .057 | 4 vs. 3 | 1.199 | 8 | 12.50 | .13 | |

| 4 | 30 | 66 | 1.15 | 256.38 | .930 | .059 | ||||||

| Behavioral | 1 | 0 | 96 | 1.15 | 429.25 | .887 | .065 | 2 vs. 1 | 1.258 | 18 | 108.69 | < .0001 |

| 2 | 18 | 78 | 1.13 | 317.21 | .919 | .061 | 3 vs. 2 | .977 | 4 | 52.50 | < .0001 | |

| 3 | 22 | 74 | 1.13 | 269.70 | .934 | .057 | 4 vs. 3 | 1.051 | 8 | 19.73 | < .05 | |

| 4 | 30 | 66 | 1.14 | 249.20 | .938 | .058 |

Notes. c is the weighting constant for computing the chi-square statistic when robust estimation procedures are used. cd is the weighting constant for the difference between two chi-square values when robust estimation procedures are used.

Table 3 presents the within-time correlations between areas of functioning at each time point. At each time point, biases in the social domain were associated with lower levels of social skills and higher levels of rejection. Poor social skills were associated with rejection at all four time points whereas aggression was related to rejection only at Time 1. Finally, aggression was related to lower social skills at all time points other than Time 4.

Table 3.

Standardized within-time correlations (and standard errors) across areas of functioning at each time point

| Biases Domain | SocSkills | Agg | Rej | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | Time 1 | |||

| PIB | −.36*** (.03) | .01 (.05) | .43*** (.04) | |

| SocSkills | −.27*** (.03) | −.49*** (.03) | ||

| Agg | .18*** (.05) | |||

| Time 2 | ||||

| PIB | −.29*** (.04) | .06 (.04) | .40*** (.04) | |

| SocSkills | −.16*** (.04) | −.40*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .11* (.05) | |||

| Time 3 | ||||

| PIB | −.24*** (.04) | .09 (.05) | .35*** (.04) | |

| SocSkills | −.15** (.04) | −.41*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .06 (.05) | |||

| Time 4 | ||||

| PIB | −.26*** (.05) | .02 (.07) | .16** (.06) | |

| SocSkills | −.06 (.07) | −.41*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .05 (.08) | |||

| Behavioral | Time 1 | |||

| PIB | −.51*** (.03) | .20*** (.04) | .38*** (.04) | |

| SocSkills | −.28*** (.03) | −.49*** (.03) | ||

| Agg | .18*** (.05) | |||

| Time 2 | ||||

| PIB | −.42*** (.03) | .08 (.04) | .33*** (.03) | |

| SocSkills | −.16** (.05) | −.39*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .11 (.06) | |||

| Time 3 | ||||

| PIB | −.39*** (.04) | .05 (.04) | .33*** (.04) | |

| SocSkills | −.15** (.04) | −.41*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .06 (.05) | |||

| Time 4 | ||||

| PIB | −.43*** (.04) | .01 (.07) | .31*** (.05) | |

| SocSkills | −.06 (.07) | −.41*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | .04 (.08) | |||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

The longitudinal stability of functioning in each area is presented in Table 4. As expected, all within-area paths were significant across time, indicating stability of functioning in each area. Specifically, biases in the social domain, social skills, and rejection exhibited moderate levels of stability. Consistent with previous work (e.g., Burt et al., 2008), aggression was highly stable.

Table 4.

Standardized path coefficients (and standard errors) for estimated paths between domains at each time point predicting variables at the subsequent time point

| Biases Domain | Subsequent Assessment Period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIB | SocSkills | Agg | Rej | ||

| Social | Time 1 | ||||

| PIB | .32*** (.04) | −.04 (.04) | .08* (.04) | ||

| SocSkills | −.17*** (.04) | .40*** (.04) | −.04 (.04) | −.18*** (.05) | |

| Agg | −.00 (.05) | −.20*** (.04) | .64*** (.05) | .08 (.05) | |

| Rej | −.10* (.04) | .08 (.05) | .21*** (.05) | ||

| Time 2 | |||||

| PIB | .29*** (.04) | ||||

| SocSkills | .33*** (.05) | −.11** (.04) | −.19*** (.04) | ||

| Agg | −.16*** (.05) | .61*** (.05) | .15** (.05) | ||

| Rej | −.05 (.05) | −.01 (.04) | .17*** (.05) | ||

| Time 3 | |||||

| PIB | .36*** (.05) | ||||

| SocSkills | .31*** (.05) | −.08* (.03) | −.16** (.06) | ||

| Agg | −.12* (.05) | .65*** (.05) | .07 (.05) | ||

| Rej | −.12* (.05) | .04 (.05) | .20** (.07) | ||

| Behavioral | Time 1 | ||||

| PIB | .39*** (.04) | −.11** (.04) | .05 (.04) | ||

| SocSkills | −.13** (.04) | .36*** (.05) | −.04 (.04) | −.16*** (.05) | |

| Agg | .16*** (.04) | −.19*** (.04) | .63*** (.05) | .08 (.05) | |

| Rej | −.10** (.04) | .10* (.05) | .23*** (.05) | ||

| Time 2 | |||||

| PIB | .18*** (.05) | −.04 (.05) | −.01 (.04) | ||

| SocSkills | −.11* (.05) | .31*** (.05) | −.12** (.05) | −.18*** (.04) | |

| Agg | .11* (.05) | −.15** (.05) | .61*** (.05) | .15* (.06) | |

| Rej | −.03 (.04) | −.01 (.04) | .16** (.05) | ||

| Time 3 | |||||

| PIB | .32*** (.06) | −.04 (.05) | .04 (.04) | ||

| SocSkills | −.06 (.06) | .29*** (.06) | −.06 (.04) | −.16** (.06) | |

| Agg | .06 (.06) | −.16** (.05) | .65*** (.05) | .10 (.05) | |

| Rej | −.08 (.05) | .03 (.05) | .17* (.07) | ||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

NOTE: only paths estimated in final models are included.

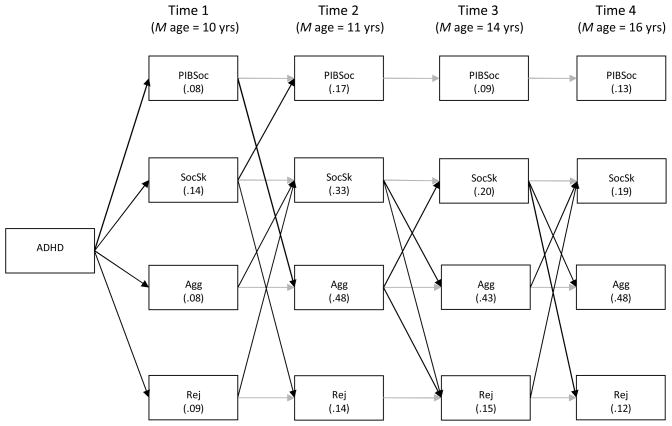

Estimates for the cross-lagged longitudinal paths are presented in Table 4. Significant paths are depicted in Figure 2. As expected, as compared to the comparison group, the ADHD group exhibited heightened biases in the social domain (estimate = .29, p < .0001), poor social skills (estimate = −.37, p < .001), aggression (estimate = .28, p < .0001), and rejection (estimate = .29, p < .0001) at Time 1. In addition, a vicious cycle between aggression and social skills was observed over time. Specifically, aggression at Time 1 was associated with lower social skills at Time 2. These lower social skills at Time 2 predicted heightened aggression at Time 3, which in turn predicted lower social skills at Time 4. A similar cycle was observed between social skills and rejection. Specifically, rejection at Time 1 was related to lower social skills at Time 2, which in turn predicted rejection at Time 3. This Time 3 rejection was related to lower social skills at Time 4.

Figure 2.

Significant pathways for final model for illusory biases in the social domain (Model 3). R2 values are in parentheses. Grey lines reflect stability estimates and black lines reflect cross-lagged paths. PIBSoc = Positive Illusory Biases in the Social Domain;. SocSk = low social skills; Agg = aggressive behavior; Rej = peer rejection. All included paths are significant at p < .05. Stability paths are depicted in gray. Although not included in the figure, within-time correlations across domains were also estimated.

Finally, biases in the social domain appeared to confer risk for rejection because of their influence on peer-based behavior. Specifically, biases in the social domain at Time 1 predicted aggression at Time 2. This Time 2 aggression, in turn, was related to rejection based on two pathways. First, Time 2 aggression predicted rejection at Time 3. We examined the significance of the indirect effect of ADHD status on peer rejection via this pathway. The test of indirect effects with the robust estimator employs the delta method for standard errors (see Muthén & Muthén, 2007, Ch. 16), and this approach has lower power than alternative tests of mediation (see Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tien, 2007). Moreover, tests of complex models such as 3-path effects exhibit lower power than traditional 2-path mediation tests (see Williams & MacKinnon, 2008); thus, indirect effects that approach conventional levels of statistical significance are reported. The test of the indirect effect of ADHD status on Time 3 rejection via this pathway (ADHD status → Time 1 social biases → Time 2 aggression → Time 3 rejection) approached conventional levels of statistical significance, p = .09. In addition, Time 2 aggression was associated with lower Time 3 social skills, which in turn predicted heightened Time 4 rejection. However, test of the indirect pathway from ADHD to Time 4 rejection via this second pathway (ADHD → Time 1 social biases → Time 2 aggression → Time 3 social skills → Time 4 rejection) was not significant, p = .12. Interestingly, poor social skills at Time 1 also predicted heightened illusory bias at Time 2, suggesting that children may develop biases for self-protective purposes when performing poorly in a particular area. Importantly, longitudinal predictions controlled for previous levels of functioning and within-time correlations, thus providing a stringent test of predictors of increases in problems over time.

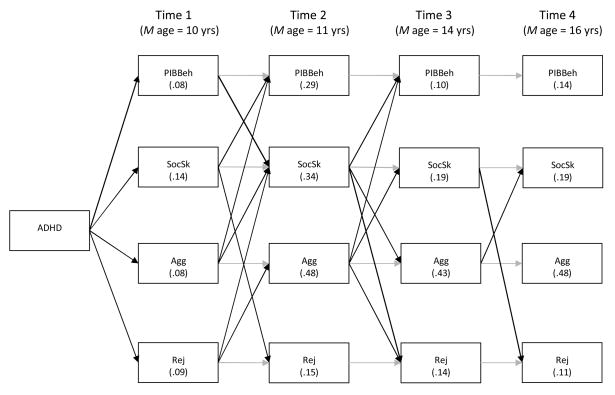

Behavioral Illusory Biases

Nested model comparisons were conducted to evaluate the fit of each model in the behavioral domain. Results, presented in Table 2, indicated that Model 1 provided poor fit to the data. Moreover, the addition of the paths in Model 2, Model 3, and Model 4 all provided significant improvement in model fit. As a result, Model 4 was selected as the final model (CFI = .94, RMSEA = .06). Given the overlap with the analyses for the social domain, only new findings are highlighted below.

Table 3 presents the within-time correlations between areas of functioning at each time point. At each time point, biases in the behavioral domain were associated with lower levels of social skills and higher levels of rejection. In addition, biases in the behavioral domain were associated with aggression at Time 1. The longitudinal stability of each area of functioning is presented in Table 4. As expected, biases in the behavioral domain exhibited moderate levels of stability.

Estimates for the cross-lagged longitudinal paths are presented in Table 4. Significant paths are depicted in Figure 3. As expected, relative to the comparison group, children in the ADHD group exhibited heightened biases in the behavioral domain (estimate = .27, p < .0001). In addition, the cascade effects between aggression, social skills, and rejection from the social biases model were replicated. As expected, biases in the behavioral domain appeared to confer risk for rejection due to their influence on peer-based behavior. Specifically, biases in the behavioral domain at Time 1 predicted poor social skills at Time 2. Time 2 social skills, in turn, were related to rejection at Time 3. Tests of the indirect effect of ADHD status on Time 3 rejection via this pathway (ADHD → Time 1 behavioral biases → Time 2 social skills → Time 3 rejection) was significant, p < .05. Time 2 social skills also predicted Time 3 social skills, which in turn were associated with Time 4 rejection. Tests of the indirect effect of ADHD status on Time 4 rejection via this pathway (ADHD → Time 1 behavioral biases → Time 2 social skills → Time 3 social skills → Time 4 rejection) approached conventional levels of statistical significance, p = .08.

Figure 3.

Significant pathways for final model for illusory biases in the behavioral domain (Model 4). R2 values are in parentheses. Grey lines reflect stability estimates and black lines reflect cross-lagged paths. PIBBeh = Positive Illusory Biases in the Behavioral Domain;. SocSk = low social skills; Agg = aggressive behavior; Rej = peer rejection. All included paths are significant at p < .05. Stability paths are depicted in gray. Although not included in the figure, within-time correlations across domains were also estimated.

In addition, there was evidence that social behavior was related to subsequent biases in the behavioral domain. Specifically, both poor social skills and aggression at Time 1 predicted heightened illusory bias at Time 2. In addition, these social behaviors at Time 2 were associated with behavioral biases at Time 3. These results are consistent with the notion that children may develop biases for self-protective purposes when performing poorly in a particular area.

Additional Models: Age, Sex, ADHD Status, and MTA Treatment Group

Given the large age range of participants at each assessment period, we ran a Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes model (MIMIC; Muthén, 1989) for our two final models controlling for participant age. In both models, all significant cross-lagged paths remained significant when age was controlled.

A second set of follow-up analyses examined whether sex moderated the longitudinal associations between areas of functioning. Given evidence that the chi-square difference test for nested model comparisons for invariance tests may be too sensitive with relatively large samples (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), we also examined whether the change in CFI for this nested model comparison exceeded the recommended .01 difference threshold (i.e., thought to reflect a meaningful difference in model fit; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). For the model with biases in the social domain, findings indicated that within-time correlations, Δχ2(24) = 35.15, p = .07, ΔCFI = .003, the stability of the four factors, Δχ2(12) = 16.55, p = .17, ΔCFI = .000., the associations between ADHD status (ADHD versus comparison group) and the four factors at Time 1, Δχ2(4) = 3.40, p = .49, ΔCFI = .000, and the significant cross-lagged paths in our final social illusory biases model were invariant across gender, Δχ2(13) = 16.54, p = .22, ΔCFI = .001. A parallel set of analyses examined sex invariance of the model with illusory biases in the behavioral domain. Results indicated that within-time correlations, Δχ2(24) = 35.67, p = .06, ΔCFI = .003, stability estimates, Δχ2(12) = 15.86, p = .20, ΔCFI = .001, associations between ADHD status and study variables at Time 1, Δχ2(4) = 5.37, p = .25, ΔCFI = .001, and cross-lagged paths, Δχ2(14) = 21.31, p = .09, ΔCFI = .003, were also invariant across sex. The ΔCFI for the addition of the stability constraint actually reflected an improvement in the model fit for the constrained model.

Next, we examined whether the strength of the significant cross-domain paths differed for ADHD participants and the comparison group. The final models were re-run with ADHD status as a moderator rather than as a predictor of study variables at Time 1. The results for the social illusory biases model indicated that within-time correlations, Δχ2(24) = 55.81, p < .001, ΔCFI = .017, and stability estimates, Δχ2(12) = 34.91, p < .001, ΔCFI = .003 were not invariant across ADHD and the comparison groups. The ΔCFI for the stability estimate actually reflected an improvement for model fit in the constrained model. Constraining the estimated cross-domain paths to be equal across groups did not result in a significant decrease in model fit, Δχ2(13) = 13.94, p = .38, and this constraint actually improved the CFI, ΔCFI = .015, suggesting similar vicious cycles and cascading across groups. Similarly, in the model with behavioral biases, within-time correlations, Δχ2(24) = 44.35, p < .01, ΔCFI = .007, and stability estimates, Δχ2(12) = 33.85, p < .001, ΔCFI = .005, were not invariant across ADHD and the comparison groups although the change in CFI suggested that these differences may not be meaningful (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Constraining the estimated cross-domain paths to be equal across groups did not result in a significant decrease in model fit, Δχ2(14) = 15.09, p = .37, and actually resulted in an improvement in CFI, ΔCFI = .013, once again suggesting similar vicious cycles and cascading effects across groups.

Finally, a set of follow-up analyses were conducted to examine whether MTA treatment group moderated the vicious cycles and developmental cascades across areas of functioning. To address this question, analyses were re-run excluding participants in the comparison group. For the final model including biases in the social domain, within-time correlations were invariant across treatment groups, Δχ2(72) = 54.80, p = .93 and this constraint resulted in an improvement in CFI, ΔCFI = .017. Next, the addition of the stability constraint did not result in a significant decrease in model fit, Δχ2(36) = 39.73, p = .31, and resulted in an improvement in CFI, ΔCFI = .001. Finally, we tested whether the significant cross-lagged paths in our final social illusory biases model differed across treatments. Results indicated that constraining the significant cross-lagged paths to be equal across treatment groups did not result in a decrease in model fit, Δχ2(39) = 42.31, p = .33, ΔCFI = .002. A parallel set of analyses for the final model including biases in the behavioral domain indicated that within-time correlations, Δχ2(72) = 67.60, p = .63, ΔCFI = .004 (with the more constrained model exhibiting a higher CFI), stability estimates, Δχ2(36) = 33.65, p = .58, ΔCFI = .006 (with the more constrained model exhibiting a higher CFI), and cross-lagged paths, Δχ2(42) = 46.87, p = .28, ΔCFI = .003, were invariant across treatment groups.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore developmental processes involved in the severe and persistent peer problems exhibited among children diagnosed with ADHD. We hypothesized that the peer problems such as rejection among these children emerge, at least in part, from failures to successfully negotiate salient developmental tasks. Consistent with this perspective, at the first assessment, children diagnosed with ADHD exhibited impairment in their social skills, aggressive and antisocial behaviors, and abilities to accurately gauge their social and behavioral competence. Moreover, these failures were related to vicious cycles such that problems in one area of functioning “spilled over” into other areas of competence and then “splashed back” to the original area over the course of development. Cascades across areas of functioning were also found, such that competence in one area had indirect effects on competence in other areas. Importantly, these results held even when controlling for age and were similar for males and females, for children with initial assignments to both the ADHD and comparison groups, and for children with ADHD who had received different MTA treatments.

One developmental task identified by Masten and Coatsworth (1998) is engaging in socially appropriate conduct, including the inhibition of aggressive tendencies and the development of socially skilled behaviors. As expected, children in the ADHD group exhibited problems in both of these areas at Time 1 compared to their peers, suggesting that these children have difficulties negotiating these important developmental tasks. Moreover, problems in each of these areas predicted increases in problems in the other areas across development. That is, Time 1 aggression predicted lower Time 2 social skills, lower Time 2 social skills predicted heightened aggression at Time 3, and heightened aggression at Time 3 predicted lower social skills at Time 4. These results are consistent with the notion that the ability to inhibit aggressive behavior may depend in part on having socially skilled alternatives for dealing with peer conflict (see Crick & Dodge, 1994). Moreover, once aggressive strategies are adopted, the availability of aggressive repertoires may interfere with children’s opportunities to learn skillful alternatives for coping with conflict.

In addition to vicious cycles between social skills and aggression, failures in both of these areas had implications for emerging peer problems across development. In fact, low social skills were associated with subsequent peer rejection at each assessment period. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that poor social skills are associated with peer rejection (e.g., Harrist et al., 1997; Newcomb et al., 1993) and suggest that the high levels of peer rejection among children with ADHD may in part reflect their inability to generate socially skilled behaviors when interacting with peers. Importantly, rejection was also associated with subsequent impairment in social skills. These findings are consistent with the perspective that social interactions with peers are essential for the development of social skills (Hartup & Sicilio, 1996; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). Insofar as rejected children have fewer opportunities for social interaction (e.g., because they are excluded; see Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005), they do not have opportunities to learn and practice socially skilled behaviors with peers, leading to decreases in their skills across time.

Aggressive behavior also had implications for rejection by peers across development. For example, there was a direct effect of aggression on rejection, such that aggression at Time 2 predicted heightened rejection at Time 3. These results are consistent with previous longitudinal research indicating that aggression is associated with later rejection (e.g., Hay et al., 2004; Little & Garber, 1995; Ostrov & Crick, 2007; Pope & Bierman, 1999). Moreover, consistent with the previous research indicating that rejection leads to aggression over time (e.g., Dodge et al., 2003; Hay et al., 2004), the results of one of the two models (i.e., those with behavioral illusory biases) indicated that rejection at Time 1 was associated with aggression at Time 2.

A second important developmental task is the formation of a cohesive sense of self (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998), including increasing accuracy regarding one’s strengths and weaknesses (Harter, 1982; Marsh et al., 1998). As expected, children in the ADHD group exhibited overly positive self-perceptions in both the social and behavioral domains when compared to their peers at Time 1. These findings are consistent with a number of previous studies demonstrating that children with ADHD tend to report fairly positive self-perceptions despite poor performance in a number of domains (e.g., Hoza et al., 2004; Hoza, Pelham, Dobbs, Owens, & Pillow, 2002). Moreover, as expected, these positive illusory biases were associated with heightened aggressive and antisocial behaviors, and lower social skills. Specifically, positive illusions in the social domain at Time 1 predicted aggression at Time 2. In addition, positive illusions in the behavioral domain at Time 1 predicted lower social skills at Time 2. The aggression findings are consistent with the notion that inflated self-perceptions may lead to aggressive and antisocial behavior when peers challenge these positive self-views (Baumeister et al., 1996). In addition, both findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the failure to acknowledge poor competence in a given domain may be related to low motivation to improve one’s abilities (Hoza et al., 2009), resulting in low competence over time. Interestingly, our hypotheses that biases in the social domain would be more strongly associated with poor social skills whereas biases in the behavioral domain would be more strongly associated with aggression were not confirmed. In fact, biases in the social domain predicted later aggression whereas biases in the behavioral domain predicted impaired social skills. It is important to note, however, that Masten and Coatsworth (1998) identify aggression and social skills as components of the same developmental task: developing socially appropriate conduct. Thus, these findings may reflect the fact that learning positive social skills and inhibiting aggressive behavior are highly related abilities. Future research should include measures of functioning across distinct developmental tasks; for example, it would be informative to explore whether biases in the academic domain predicted later academic but not social functioning to further explore this important point.

Importantly, the results also provided support for the hypothesis that positive illusory biases would have indirect effects on peer functioning. In fact, biases in both domains were indirectly related to peer rejection via their influence on aggression (for social illusory biases) and poor social skills (for behavioral illusory biases). However, it is important to note that the statistical tests for indirect effects from ADHD to later peer rejection via these pathways were significant for behavioral biases to Time 3 rejection only. Nonetheless, two of the three remaining indirect pathways of ADHD status to rejection approached conventional levels of statistical significance (p < .10) despite including 3-path and 4-path effects (see Williams & MacKinnon, 2008) and using a mediation test (the delta standard error method, Muthén & Muthén, 2007, Ch. 16) that may be relatively underpowered relative to bootstrapping alternatives (see Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2007). Overall, then, these findings do provide some evidence to suggest that positive illusions may serve as an important mediator of the association between ADHD and rejection by peers, although some of these pathways should be interpreted with caution as they did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

This study is one of the first to examine the developmental implications of positive illusory biases for adjustment, and the findings suggest that, despite some advantages (see Taylor & Brown, 1988), there may be maladaptive consequences to overly positive self-perceptions. In fact, overly positive self-perceptions were associated with impaired functioning in the peer group over time, and these negative behaviors were in turn related to peer rejection. Interestingly, these overly positive self-perceptions (as indicated by the bias scores) appeared to reflect relatively “normal” self-reports of competence despite low levels of actual competence. Thus, it is possible that attempts to feel good about oneself, when reality does not warrant it, can cause further problems for struggling children. That is, in the face of impaired functioning, these children attempted normative self-perceptions, resulting in an overestimation of competence. This overestimation, in turn, predicted later problem behaviors.

Interestingly, negative peer behavior was related to later positive illusory biases. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that positive illusory biases serve a self-protective function for at-risk children (for a review of theoretical accounts of the positive illusory bias among children with ADHD, see Owens, Goldfine, Evangelista, Hoza, & Kaiser, 2007). In effect, if at-risk children adopt relatively positive self-views in an effort to cope with failures or limited competence, then impaired functioning should lead to increases in biases in self-perceptions over time. Consistent with this perspective, results indicated that poor social skills at Time 1 were associated with positive illusory biases in the social domain at Time 2. Moreover, poor social skills and aggressive behavior at Time 1 predicted positive illusory biases in the behavioral domain at Time 2, and poor social skills at Time 2 predicted positive illusions in the behavioral domain at Time 3. These findings are also consistent with previous findings suggesting that children with ADHD tend to inflate their self-perceptions in the domains of greatest deficit (Hoza et al., 2004; Hoza et al., 2002).

Two additional interesting patterns also emerged in the results. First, there appear to be multiple vicious cycles and cascading effects among areas of functioning across development. These findings suggest that there are a number of indirect effects among overly-positive self-perceptions, social skills, aggression, and peer rejection. As a result, failure in one area may have both direct and indirect effects on functioning in other areas across development. Second, these effects appear to be more prominent in late childhood and early adolescence than in later adolescence. For example, in the model with positive illusions in the social domain, the addition of cross-lagged paths between these biases and peer-based behavior from Time 2 to Time 3 and from Time 3 to Time 4 did not improve model fit (although it did in the model with behavioral illusory biases). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the effects of self-perceptions on behavior are especially likely during early adolescence, when a focus on others’ views of the self becomes especially salient (see Harter, 1999). In fact, there were a relatively high number of significant cross-lagged paths between Time 1 and Time 2 (as compared to the other time lags). Given the relatively high importance placed on successful peer functioning during middle childhood and early adolescence (e.g., Berndt, 1996; Bukowski & Kramer, 1986; Hartup, 1992), it is possible that impairment in these areas is especially problematic during these developmental periods. However, this possibility is speculative and awaits further empirical investigation, especially since the addition of these cross-lag paths did improve model fit in the model for behavioral illusory biases. Moreover, it is also possible that these effects simply reflect the shorter time lag earlier in the study relative to later in the study. It is likely that cross-lag effects will be more difficult to detect across longer periods of time. Future studies should explore cross-lag paths across middle childhood and adolescence with uniform spacing of assessments to further address this important point.

The findings from this study have a number of implications. First, the results suggest that the peer problems typical of children with ADHD may reflect the failure of these children to successfully negotiate important developmental tasks (e.g., to develop accurate self-perceptions), a perspective which is in line with the developmental psychopathology perspective (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). As a result, researchers and clinicians interested in understanding impairment among children with ADHD may benefit from increased attention to normative developmental processes and the ways in which children with ADHD struggle with these typical developmental challenges. In fact, the cross-domain paths among areas of functioning were the same for ADHD children and the comparison group. These findings suggest that the same processes may be involved in peer problems in both groups, with ADHD children simply exhibiting more difficulties in these areas.

Second, our findings have important implications for interventions aimed at improving peer problems among children with ADHD. There are two different “levels” at which our findings might be interpreted. At the more conservative level, we might conclude that intervention programs may benefit from intervening at multiple levels and areas of functioning (e.g., developing more accurate self-perceptions, lowering aggressive behavior, and improving social skills). In fact, given the findings of negative cascades and vicious cycles across time, it is also possible that interventions might lead to positive cascading effects (e.g., improvements in social skills leading to reductions in rejection and aggression), although impediments such as negative reputations with peers (see Hoza, 2007, for a discussion) may prevent such cascading effects. Also, these interventions may be most effective during specific developmental periods. For example, early social skills interventions might be especially helpful in reducing peer rejection. Given the many cross-domain paths associated with social skills, this level might be especially important. Nonetheless, it is hard to ignore prevailing work that documents that social skills training is of limited effectiveness with externalizing children (Bierman, 2004), suggesting that more drastic measures may be needed.

Hence, at a less conservative level, an argument can be made that the cascading effects of impaired functioning in these interrelated social and behavioral functioning domains may warrant a more comprehensive approach to intervention than has heretofore been considered. Given that poor social and behavioral functioning are potent predictors of later maladaptation that persists into adulthood (e.g., Burt et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2005), and that we have shown here that processes involved appear to be similar for children with ADHD and comparison children, an argument can be made that a comprehensive social/behavioral curriculum that addresses skill development in these areas might be a critical piece of educational curriculum to be administered in schools across childhood and adolescence. Although such a position is likely to be unpopular with school administrators who are under grave pressure to improve academic outcomes, our results suggest that social and behavioral maladaptation also has devastating effects on developmental outcomes. Nonetheless, such a shift may be beyond what our educational milieu can accept at the present time.

Regardless of whether the more or less conservative approach is taken, however, the results of this study contribute to an emerging literature documenting the utility of a developmental cascades perspective (Burt et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2005), in which impaired functioning in one area “spills over” into other areas. Although the idea of transactional processes across areas of functioning is not new, we agree with Masten and colleagues (2005) that more systematic studies of these associations over time greatly enhance our understanding of adaptation across development.

Given the interesting implications of the present study, it is important to consider the findings in the context of study strengths and limitations. This study has a number of strengths, including the large sample size, the longitudinal design, the inclusion of children with ADHD and a comparison group, and the inclusion of multiple reporters (i.e., self, teacher, and parent) to assess study constructs. In addition, the statistical methods employed are able to accommodate missing data and allow for appropriate treatment of skewed variables. Finally, some researchers have criticized the use of difference scores (e.g., self-report minus teacher report) when measuring positive illusory biases because resulting correlations may simply be an artifact of actual competence. However, it is important to note that, in the present study, effects of positively biased self-perceptions on later peer-based behavior persisted even when controlling for earlier functioning (e.g., aggressive conduct and social skills). These results suggest that it is unlikely that the associations between positive illusory biases and adjustment are simply an artifact of the low levels of actual adjustment typical among children with positive illusory biases.